History

Morgraig castle was built between 1243 and 1267 by the Anglo-Norman de Clare lords or the Welsh rulers of Senghennydd. Relations between them were peaceful until the Second Barons’ War of 1264-1267, which was a civil war in England between the lords under the leadership of Simon de Montfort and the supporters of King Henry III. Initially, Gilbert II de Clare and Gruffydd ap Rhys, Lord Senghenydd, were allies supporting the party of Simon de Montfort, but in 1265 Gilbert II joined the royal side and the following year imprisoned Lord Senghenydd. In 1267, de Clare temporarily lost control of the lands near Morgraig Castle when Llywelyn ap Gruffudd destroyed Llangynwyd Castle. Lord of Senghennydd would then be able to obtain the stone needed to build the castle, known to be the so-called Sutton Stone, sourced from the only quarry near Ogmore by Sea. Gilbert de Clare responded by beginning construction of the larger Caerphilly Castle in 1268. The unfinished castle Morgraig may have been abandoned at this point, be it by the Gruffydd ap Rhys or by Gilbert de Clare, as it was no longer strategically important to him and most of the resources were used in the construction of castle Caerphilly.

The abandoned castle could be re-occupied at the beginning of the 14th century by Rhun ap Griffith Fychan ap Grono, as indicated by the Mathew family pedigree, who was to come from “Castell Kibur, between Draenan Penygraig and Cefn On”. Morgraig was the only castle between these particular points. While no traces of permanent settlement have been found, the presence of a Welsh tenant in the area would not have been exceptional in the early 14th century. In the nearby Rudry and Ruperra, extensive estates were then granted by King Dafydd ap Grono while Glamorgan was under the custody of the ruler, awaiting the partition of the estates after the family de Clare. Dafydd remained loyal to the king in 1316, when his compatriots from Senghennydd rebelled under Llywelyn Bren, leaving his lands ravaged.

The last time the castle could be captured by the Welsh insurgents in 1316. They occupied the border hills and fortified the obvious crossing-places with strong entrenchments, trying to repel the royal forces gathering at Cardiff to raise the siege of Caerphilly Castle. The royal army, however, flanked these fortifications crossing the ridge to the east under the Rudry and turned to capture them from the rear. This fleeting event was likely to be the last attempt to use the military potential of Morgraig.

Architecture

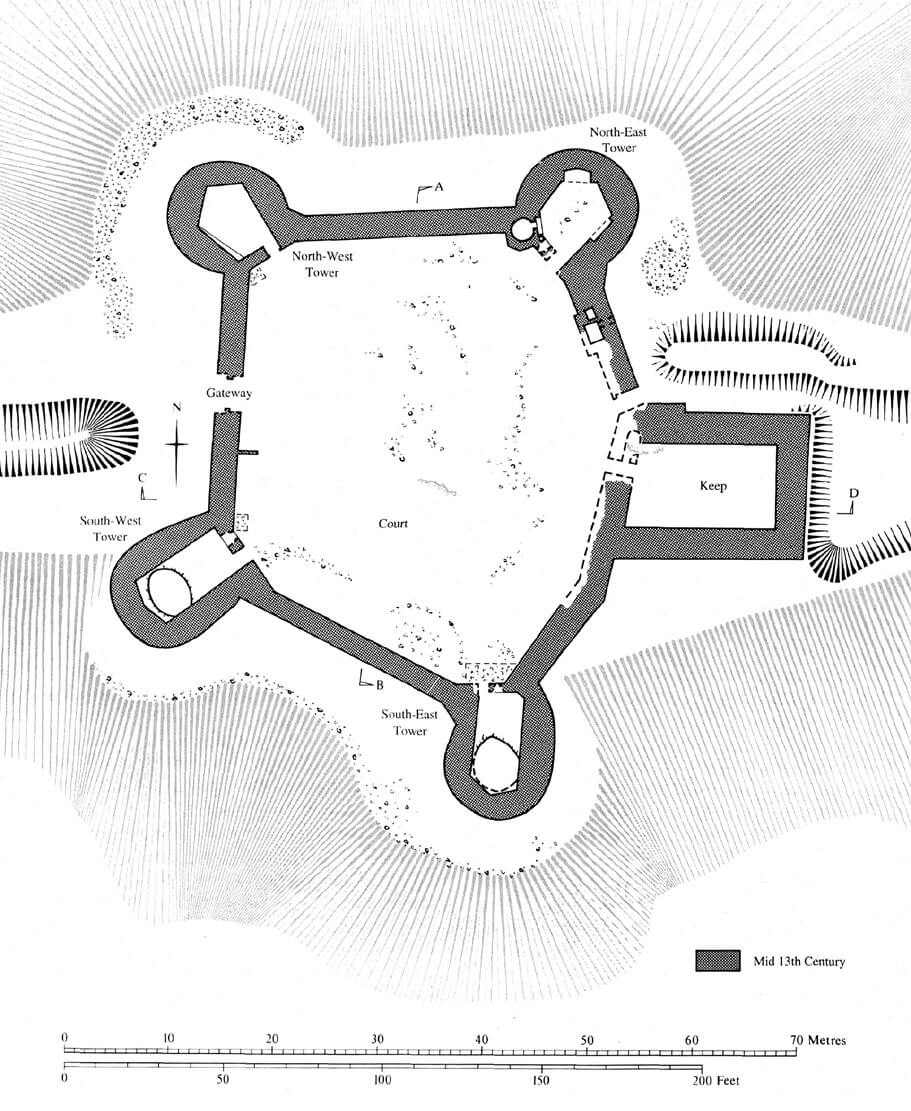

The castle was situated on the crest of Craig Llanisien, elongated roughly on the east-west line, dominating the lowland, coastal part of Glamorgan and Cardiff to the south. The commanding perspective to the south contrasted with the limited view to the north toward Caerphilly. There, a wide depression, deepening further west to Cwm Nofydd, separated the castle from the higher and wider limestone ridge called Cefn Caraau. From the west, near the castle, there was an old Roman road that crossed the ridge, connecting Cardiff with Caerphilly and Brecon.

The castle was planned as a pentagonal structure with a courtyard diameter of about 38-42 meters. About 2.3-2.5 meters thick above an external batter, the curtains of the defensive walls were reinforced by five towers, including four on the plan of an elongated horseshoe and one four-sided. The latter was situated at the highest point of the terrain and had a considerable dimensions of about 14 x 19 meters, so it may have acted as a keep. On its northern side, in the curtain of the wall, there was a small postern 1.4 meters wide, and a little further, the chutes of the latrines. The main gate was located in the center of the west curtain. It was probably an ordinary passage in the wall. The area fell in front of each of the horseshoe towers, only behind the keep was the extension of the ridge. The southern part of the site was extended beyond the natural slopes. It is possible that the castle area was leveled there and artificially extended outward beyond the ridge, which would explain the larger size of the southern towers as designed to support the southern curtains.

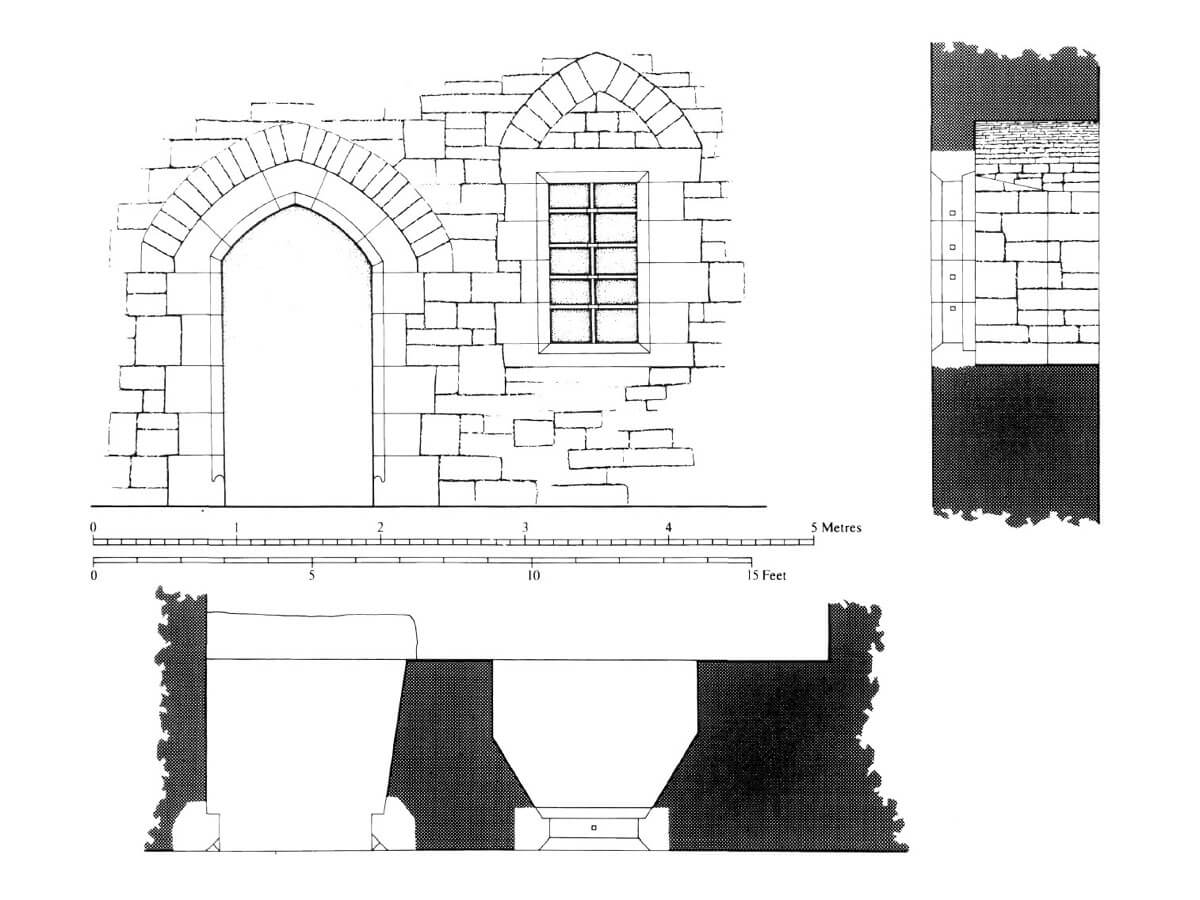

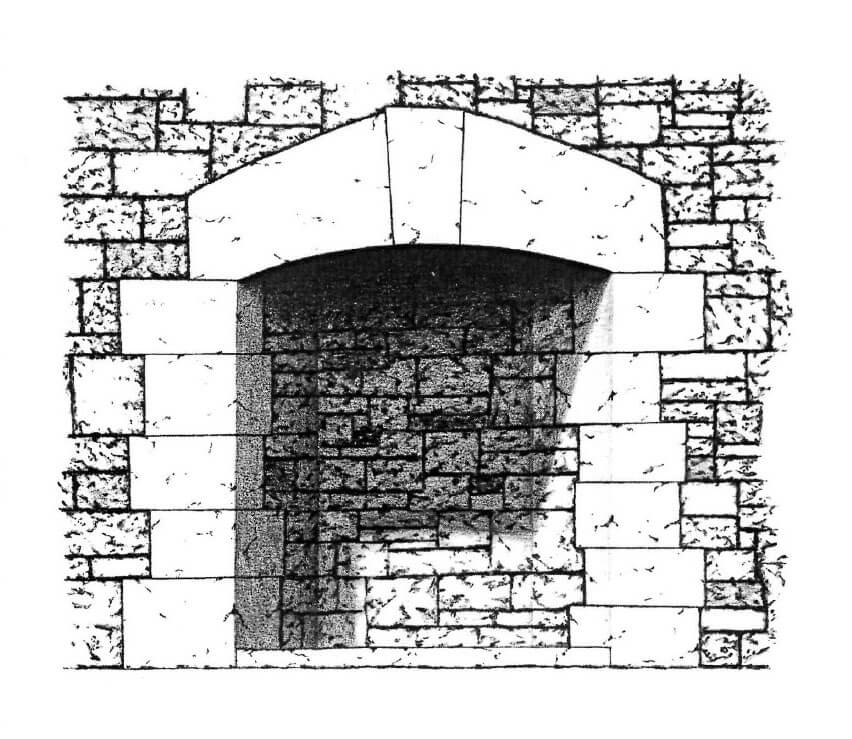

Among the horseshoe towers, the northern ones were shorter (about 10 meters in diameter), and the southern ones were more elongated (about 14 meters long), but all of them protruded completely in front of the curtains of the walls, giving very good opportunities for side fire of the adjacent curtains and mutual protection of the towers. Straight walls were directed towards the ward, each of which was equipped with an entrance to the ground floor and a single window. They had to at least two, and probably three storeys high. The lowest ones were not structurally connected with the first floors, only from the first floors spiral stairs in thickened sections of the walls led to the second floors. Wooden, external stairs placed on stone platforms probably led to the first floors, they could also be connected with the wall-walks in the crown of the curtains. In the ground floor there were single utility rooms (pantries, warehouses), with the exception of the north-east tower where the kitchen was located. Its oven was positioned in a shallow recess with a square shaft facing downwards which ended at floor level with a square opening. The shaft was probably used to remove ash from the oven, which could be thrown out through the lower opening at the floor level. The large oven could only be accommodated by projecting a polygonal block towards the courtyard. The upper floors of the towers, in addition to defensive functions, could have also residential role (elements of fireplaces were found). Presumably, they were connected with the wall-walks on the curtains.

The keep had dimensions of 14.2 x 19.2 meters, with massive walls up to 3 meters thick. In plan its shape was slightly trapezoidal, with a sloping western wall with an entrance from the courtyard. The communication between the floors was probably provided by stairs embedded in the wall thickness, which was used by the wall thickening in the north-west corner, placed right next to the aforementioned gate. There was no fireplace in the ground floor chamber, so it probably served as a storage facility. The residential role had to be played by the rooms on the floors, after which profiled and worked stone blocks were found.

The plan of the castle does not allow to clearly specify the builder. The system of corner flanking towers integrated with the adjacent curtains was a 13th-century novelty in Wales connected with Anglo-Normans, while the very simple archaic gate and the horseshoe (D-shape) form of the towers suggests Welsh builders rather. Whoever started the construction of the castle, most likely never finished it, as no building materials from roofs or internal buildings were found in the fortress. Also, work on digging the moat or ditch has not started.

Current state

The castle has not survived to modern times. Only densely overgrown foundation and ground parts are visible, discovered during archaeological works in 1903, in the highest places, up to 3-4 meters in height. Admission to ruin’s area is public, despite the fact that the castle terrain is privately owned. A short marked path leads to it from the road.

bibliography:

Davis P.R., Castles of the Welsh Princes, Talybont 2011.

Davis P.R., Forgotten Castles of Wales and the Marches, Eardisley 2021.

Davis P.R., Towers of Defiance. The Castles & Fortifications of the Princes of Wales, Talybont 2021.

Salter M., The castles of Gwent, Glamorgan & Gower, Malvern 2002.

The Royal Commission on Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales, Glamorgan Later Castles, London 2000.