History

In the second half of the 11th century, when the Norman infiltration of South Wales began, the rights to the local lands belonged to the Welsh ruler Rhys ap Tewdwr. He made an alliance with William I the Conqueror, thanks to which his territory was protected from seizure. The agreement expired in 1093, when Rhys died in a frontier skirmish, and the Norman baron Roger de Montgomery took the opportunity and occupied South West Wales. To establish his dominion, he built the castles at Cardigan and Pembroke, and gave land to the knights who provided him with military assistance. Manorbier received Odo de Barri, which at the end of the eleventh century erected the first timber – earth fortifications. His son, William de Barri, strengthened this first stronghold by a stone, rectangular building in the keep style, in the thirties of the twelfth century. It served as both the main administrative and ceremonial facilities, as well as the place of final defense.

Around 1146, the famous scholar and chronicler Gerald de Barri was born in Manorbier, better known as Gerald of Wales. He was the fourth and youngest son of William de Barri and his wife Angharad de Carew, daughter of Lord Gerald of Windsor. Gerald of Wales wrote of his birthplace and upbringing (“Maenor Pyrr”), that it was by far the most pleasant seat in the whole of the Wales, perfectly defended by towers (“turribus et propugnaculis eximium”), situated on the top of a hill stretching towards the seaport, near a fishpond, surrounded by a hazel grove, an orchard, a vineyard and a mill. Although some of Gerald’s family acquired estates in Ireland, and he himself made an ecclesiastical career, the Lords of Manorbier were not persons of great importance. The lordship consisted of the estates of Manorbier, Penally and Begelly and was burdened with four or five knightly feudal fees. For this reason, Manorbier Castle was not a very extensive and its buildings were built over a long period of time, as the family had the means to expand. In terms of importance, the only exception in the family was Lord David II, who lived from 1262 to 1280, and was appointed justiciar in 1267, under whose authority the castle chapel may have been built.

In the 1230s, the castle’s fortifications were significantly strengthened, due to the fights between the Anglo-Normans and the Welsh prince Llywelyn ap Iorwerth. The wooden fortifications were then replaced by a stone wall with towers and a gatehouse. It is possible that this is how the castle escaped attack during the numerous Welsh-English wars of the 13th century. The first attack on Manorbier did not occur until 1327, when the castle was captured by Richard de Barri, in a dispute with members of his own family (after the raid, Richard was accused of stealing £500 worth of property and killing Edmund Barry, a servant of Lord David V). In 1359, the castle passed into various ownership, and the disputes that ensued dragged on for decades. Eventually, King Henry IV granted Manorbier to the Countess of Huntingdon, who had been Edward III’s mistress, but by this time the castle had already seen its day and was probably in partial ruin. Quick renovations, to garrison Manorbier, were carried out in 1403, out of fear of Owain Glyndŵr’s Welsh rebels, but ultimately no fighting took place for the castle.

In the first half of the 15th century Manrober was owned by John Holland, Earl of Huntingdon, Duke of Exeter from 1444. His son Henry was captured in the Wars of the Roses in 1461 and died without heirs in exile in 1475. The castle was then owned by the English Crown, but was occasionally granted to different tenants. In 1461 Edward IV gave Manrober, along with other estates, to his sister Anne, Duchess of Exeter, and in 1484 Richard III gave the castle to Richard Williams, one of the doorkeepers of the King’s chamber. Then in 1487 Henry VII gave Manrober and Penally in perpetuity to his mother, Lady Margaret, Countess of Richmond. She died in 1509, after which her grandson Henry VIII gave the castle and surrounding estates in 1525 to his illegitimate son, Henry Fitzroy, Duke of Richmond and Somerset. These owners and subsequent tenants in the 16th century were interested only in the rents received from Manorbier. Most of them probably did not live in the castle, leaving it in the care of their servants and keepers. For this reason, the castle was not subject to any major alterations in the late medieval and early modern period.

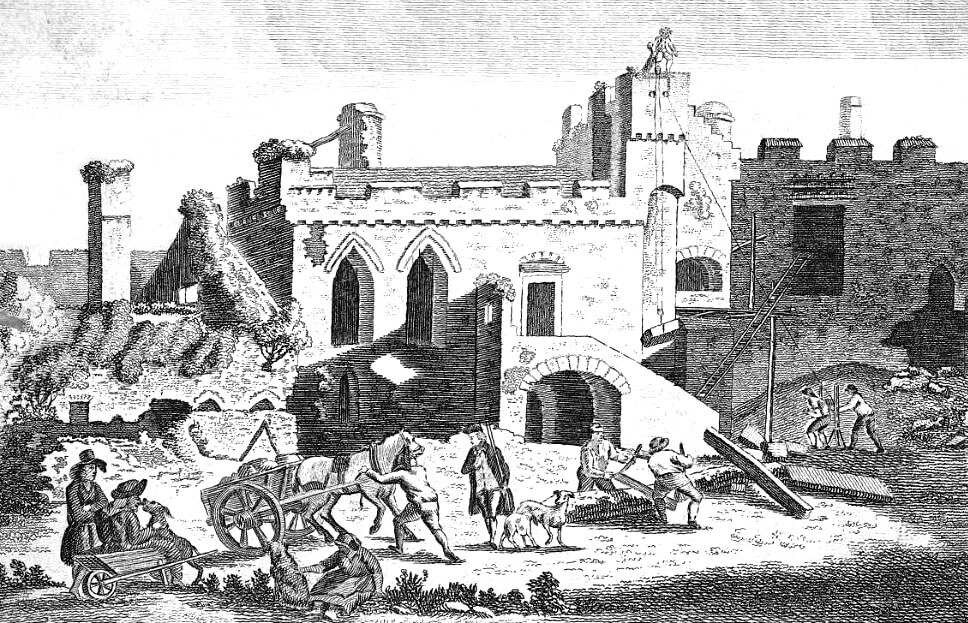

The 16th century was a quiet one for Manorbier, as it was for Wales as a whole, with its internal tensions easing under the reign of the Tudor dynasty, which prided itself on its Welsh origins. During the 17th century civil war, the castle was hastily refitted for defence and garrisoned with loyal supporters by its then owners, the Philips family. Efforts were concentrated on digging trenches around the castle and drilling musket holes. Despite these modifications, the castle surrendered without a fired shot in 1645, shortly after the arrival of Parliamentary forces under Rowland Laugharne. Like many castles, it was subsequently abandoned, but it probably escaped major demolitions that would have prevented further military use.

The decayed castle continued to be owned by the Philips family in the second half of the 17th century. Sir Erasmus Phillips did not use it for residential purposes, but merely converted it into a farmhouse, probably abandoned by the mid-18th century. The castle’s remote location and easy access to the sea, as well as its many storage rooms, made Manorbier an ideal location for smugglers, who used it for much of the 18th century and early 19th century. The castle was first restored in 1880 by the then tenant of Manorbier, Joseph Richard Cobb, who stabilised the neglected walls. The repairs enabled the castle to be reused during World War II, when it was used to house RAF staff and personnel.

Architecture

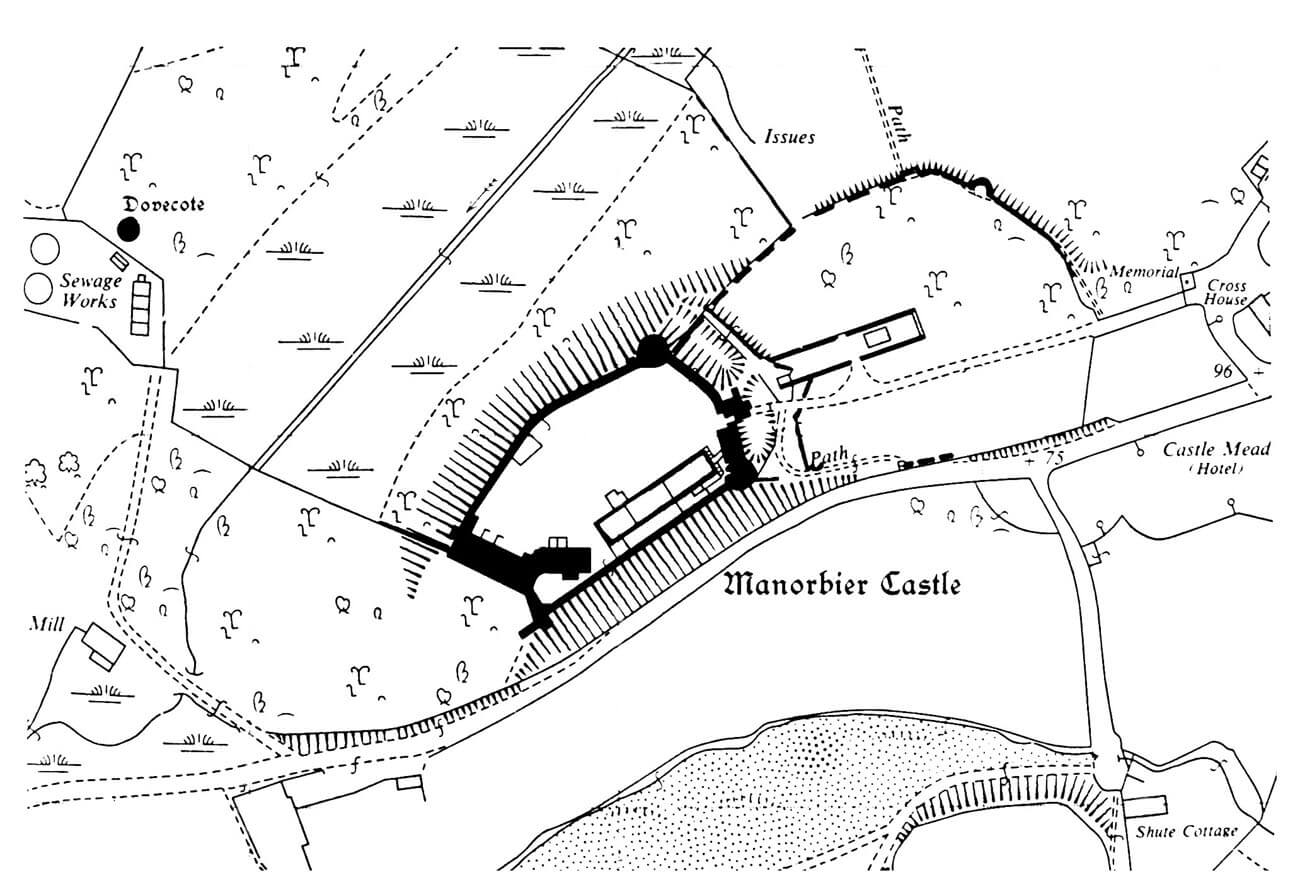

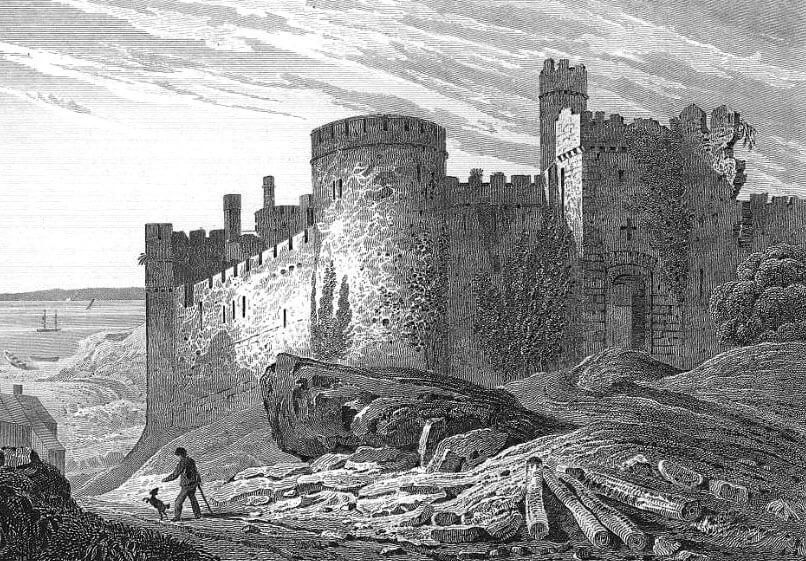

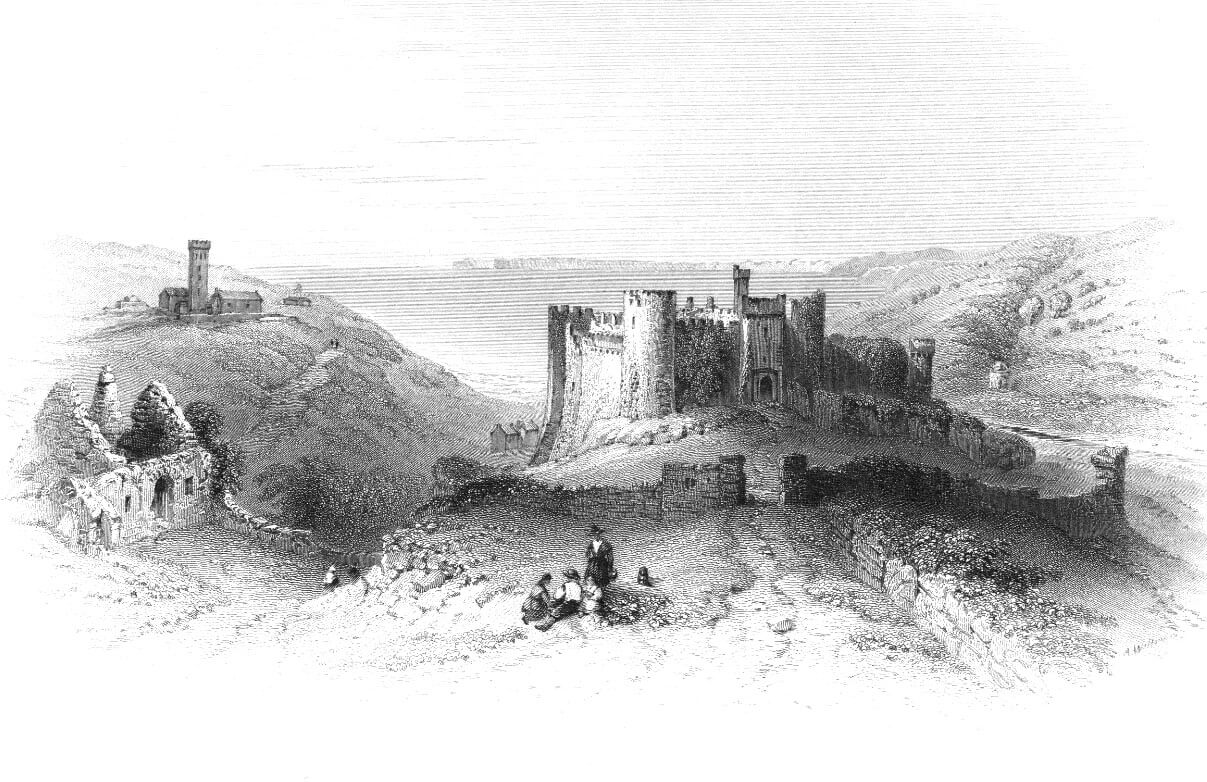

The castle was situated on an elongated hill, limited by two streams on the longer sides, that is from the north and south. It flowed down narrow valleys to the west, where found an outlet to Manorbier Bay in close proximity. The slopes of the hill were gentler only on the eastern side, where the access road to the castle was secured with a transverse ditch. Behind it was an elongated outer bailey measuring about 90 x 60 meters, fortified by a stone wall with small towers from the 13th or early 14th century. The area on the western side of the castle, where both streams found an outlet, and also partly on the north and south, were marshy and wet in the Middle Ages, increasing the defensive strength of the whole complex. However, the hill itself was not high and apart from the view of the bay, it did not provide a distant view into the foreground.

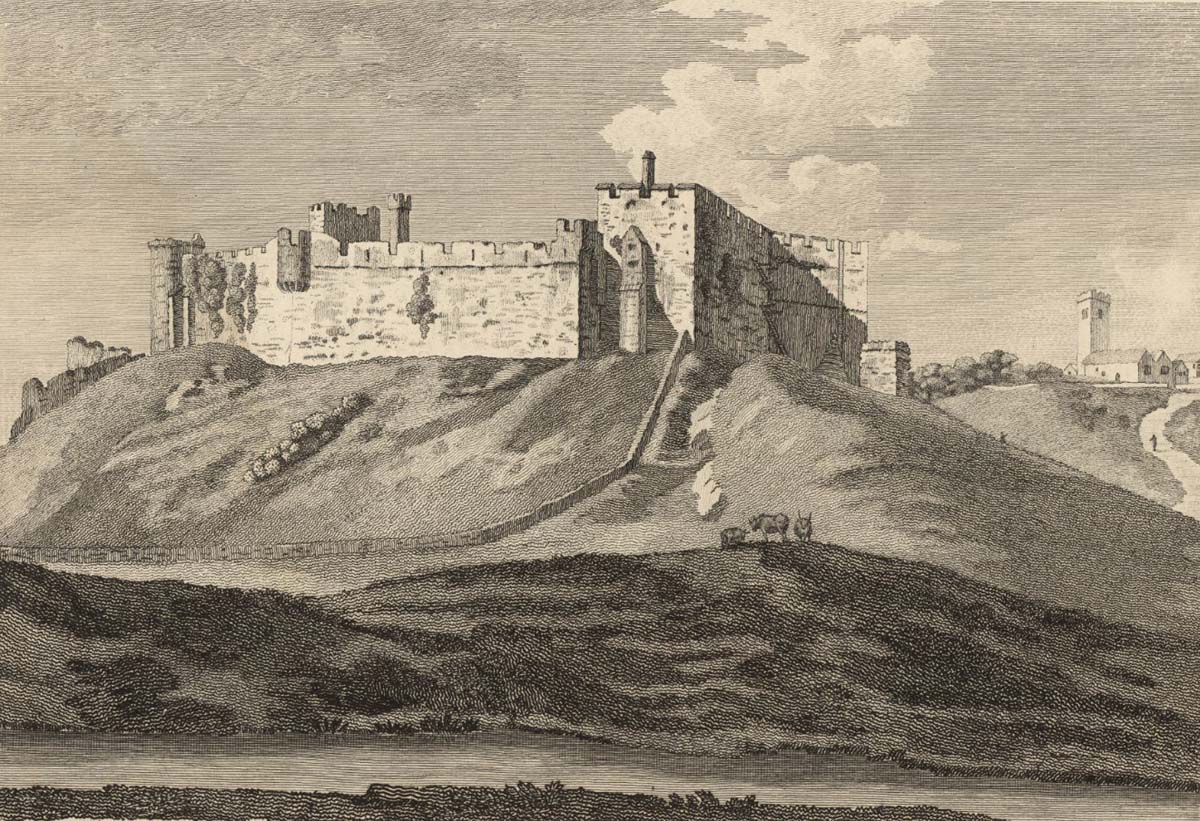

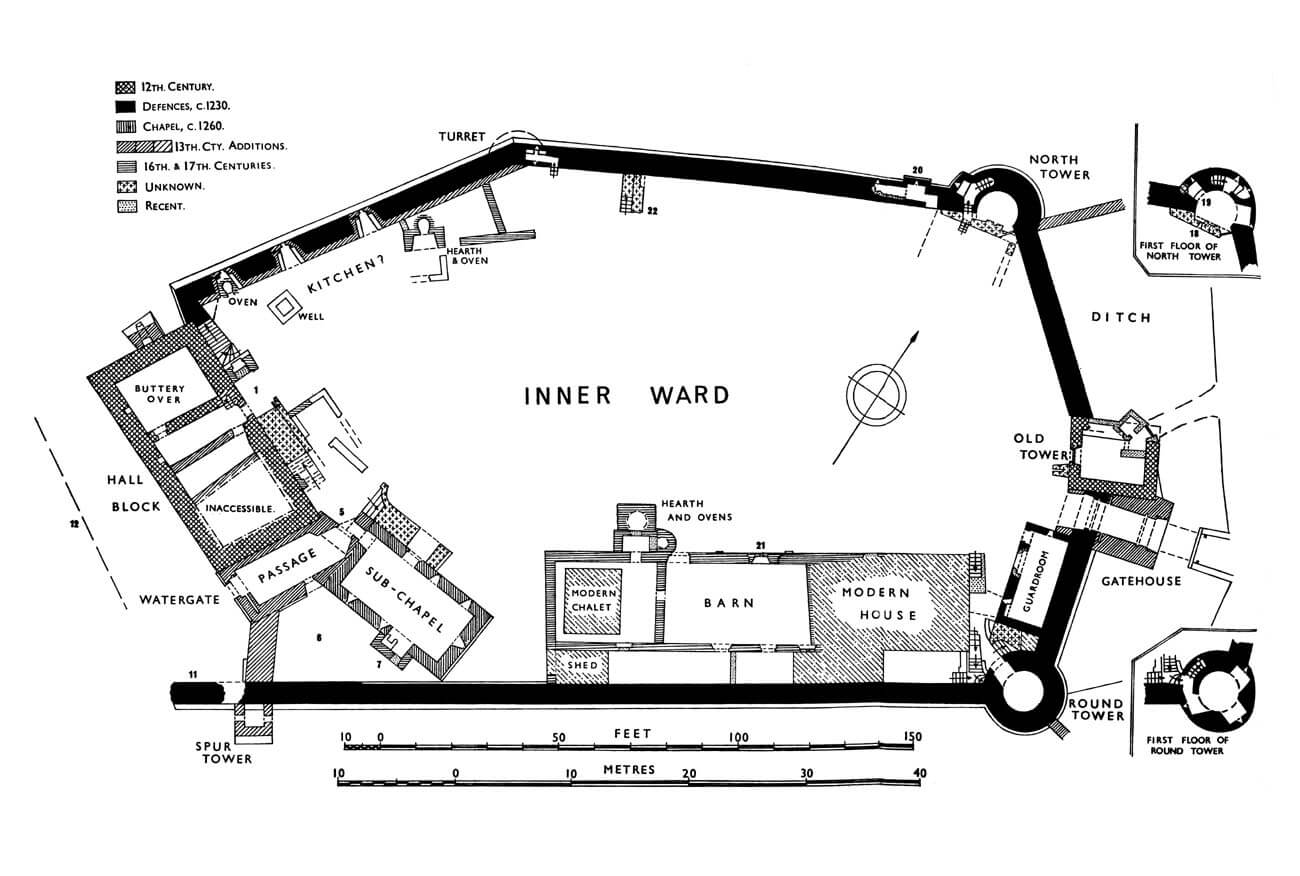

The castle was built of light grey limestone, durable and yet sufficiently malleable to be roughly cut and rather irregularly laid, and even shaped into corners, corbels or voussoirs. The core of Manorbier was laid out on a polygonal plan with a large courtyard measuring about 67 x 44 metres, surrounded by a straight southern curtain wall and slightly bent northern, eastern and western curtain walls, the latter mostly filled by the hall building. The wall was originally only 3-4.5 metres high to the level of the wall-walk. The highest sections faced the ditch on the eastern side, but on the inner side the height of the wall was fairly uniform, despite the unevenness of the terrain. As late as the 13th century the wall was raised by about 1.8 metres. The crowning of all the curtains, both before and after the raise, was a battlemented parapet, in the later Middle Ages in places mounted on corbels (not creating machicolation). In the most endangered sections, arrwoslits were pierced in the merlons.

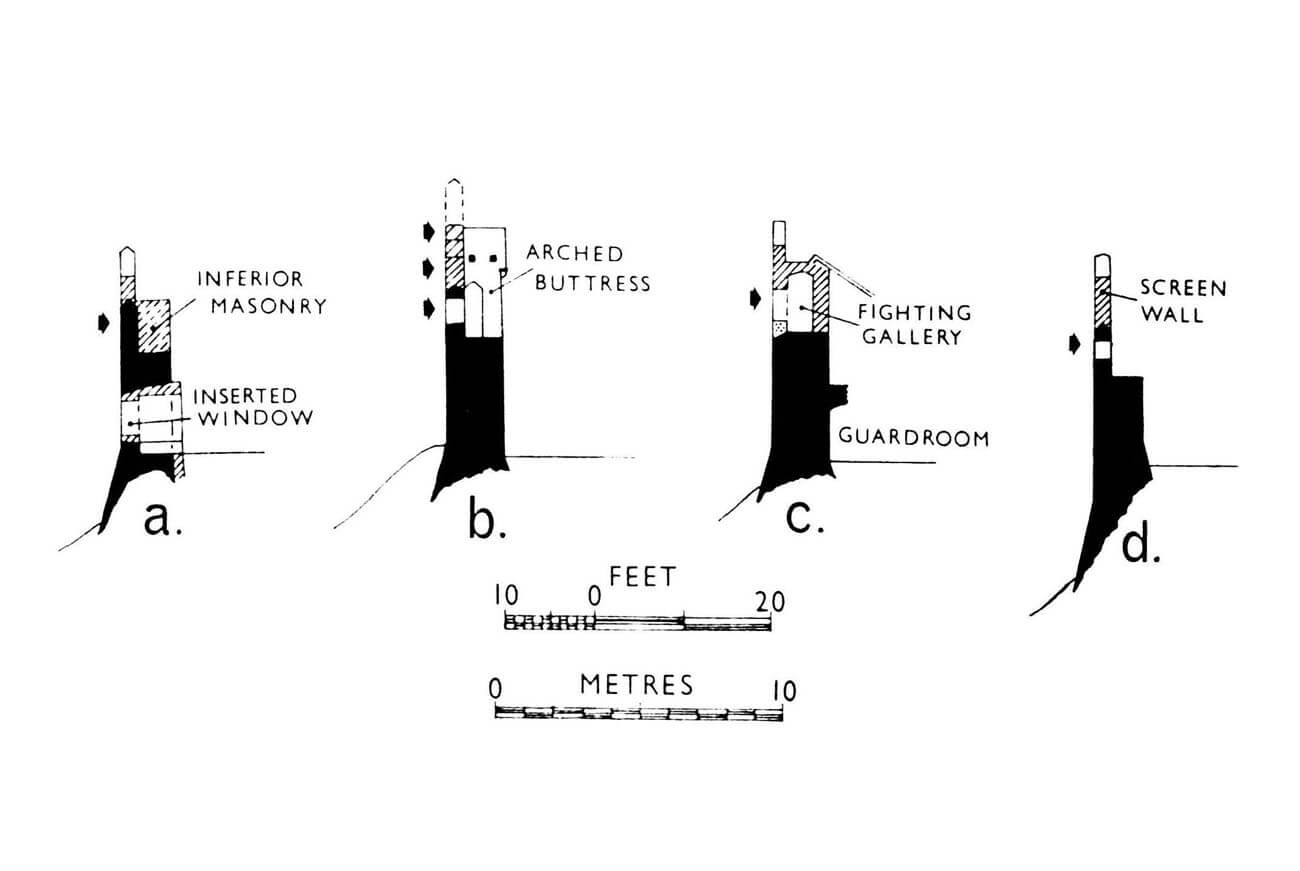

The raising of the defensive wall on the north-eastern side was carried out in two stages. In the first one, the original opened (unroofed) wall-walk, thanks to the large width of the curtain, was transformed into a vaulted gallery, in order to provide communication with the guard room above the gate. In the second stage, the new wall-walk above the gallery was additionally raised. A similarly vaulted gallery was created on the eastern section of the perimeter (on the other side of the gate), although the curtain was raised there only as part of a one construction action. As in other sections of the perimeter, the spaces between the old merlons were bricked up, and the arrowslits in them were left. In the southern part of the castle, only the parapet was raised, without raising the level of the wall-walk. In the more endangered part closer to the bailey, a new combat level was probably created using wooden structures, while the remaining part of the high parapet was rather dummy.

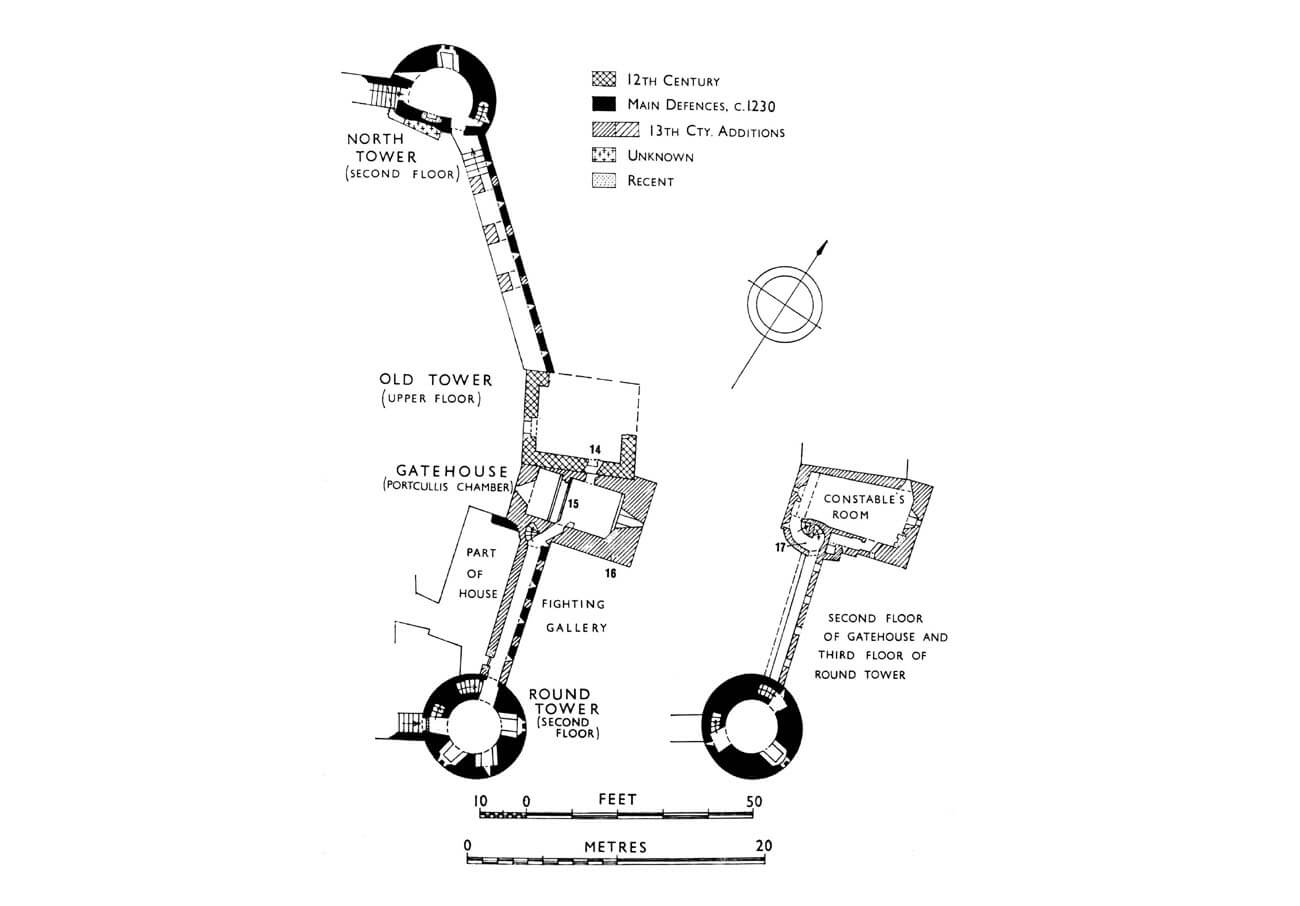

The entrance to the courtyard was on the eastern side of the castle, facing the outer bailey. Originally, it was an ordinary portal pierced in the perimeter wall, flanked by an older, simply made, quadrangular tower measuring about 7.5 x 6.2 meters, with walls only about 1 meter thick. Probably at the end of the 13th century this tower partially collapsed, and a new quadrangular gatehouse with a vaulted passage in the ground floor was built to the south of it. The new gate used part of the southern wall of the old tower, to which it was attached at an angle. The passage was now closed with two portcullises and double-leaf door, preceded by a bridge over the ditch. Above the passage there were two more storeys, accessible only from the wall-walk and above by a spiral staircase in the thickness of the wall, ended with an observation turret. The vaulted room on the first floor housed the mechanisms operating the portcullises. Its floor was on two levels, marked by the course of a section of the older defensive wall. The room on the second floor was residential, equipped with a fireplace and a latrine. It was lit by windows on every side of the world, including two equipped with stone seats and one converted from the arrowslits of the old tower. The gatehouse was topped with an unroofed platform with a parapet mounted on corbels.

The defensive wall of the castle was reinforced in the corners by a semicircular northern tower and a cylindrical south-eastern tower, both with a diameter of about 7 meters. Of these, the south-eastern one was projected far enough into the foreground to protect the neighboring curtains. The northern one was slightly shallower at the front, so its flanking capabilities were limited. On the southern side the curtain wall was extended beyond the perimeter, where a slender quadrangular latrine turret was erected. The central part of the northern section of the wall, where it bent, was reinforced by a smaller bartizan with a double latrine, suspended on nine corbels. The latrine at the bartizan was located in the thickness of the wall, but it was characterized by a lack of privacy due to the lack of a door. The double latrine was similarly open in the thickness of the wall at the northern tower. The latrines facing outwards with two corbeled projections, were also located in the thickness of the wall of the north-western corner of the castle. Above them, the widened part of the wall could have served as a small observation and defense platform.

The northern tower was originally partially opened from the courtyard side, or closed with a wooden screen. An unusual stone rear wall was created only on the third, highest storey, where it was supported by the vault of the lower floor. What is more, a chimney was suspended on two corbels on the stone rear wall, despite the fact that there was no fireplace on the highest floor. Therefore, the fireplace had to be located in the rear wooden screen. Another unusual solution was a latrine in a small projection, in a place adjacent to the staircase landing, connecting the first and second storeys in the thickness of the wall. This latrine was lit by a single slit, which also flanked the curtain of the defensive wall. The room on the second storey was covered with the above-mentioned low barrel vault, with a heavy reinforcing arch at the back, which helped to support the rear wall of the highest floor. In addition, two recesses for arrowslits were made in the walls of the second floor. The third floor was accessible only from the crown of the adjacent defensive wall. It was equipped with a narrow window with stone seats and an observation slit without a recess with limited fire capabilities. Very narrow stairs led higher, to an opened combat platform, with a parapet protruding on corbels.

The southeastern tower had four floors, three of which were connected by a staircase in the thickness of the wall, set only in the part facing the courtyard, so that the wall would not be weakened on the most endangered front side. The lowest floor, devoid of vertical communication, was an unlit storage chamber. The second floor, accessible by stairs from the courtyard and equipped with three arrowslits (two facing the adjacent curtains, one in the foreground), had exclusively military functions. The third floor was connected to the wall-walk. It was equipped with three openings, one of which was a slit and the other two were narrow, two-light windows, made in a simple way, without the use of ashlars. Although all the openings were equipped with side stone seats, the room had no other residential amenities (e.g. a latrine, fireplace). The highest floor was lit only by one similar two-light window, but two arrowslits were placed in the stair landings. The tower was originally crowned with a battlemented parapet with arrowslits in the merlons.

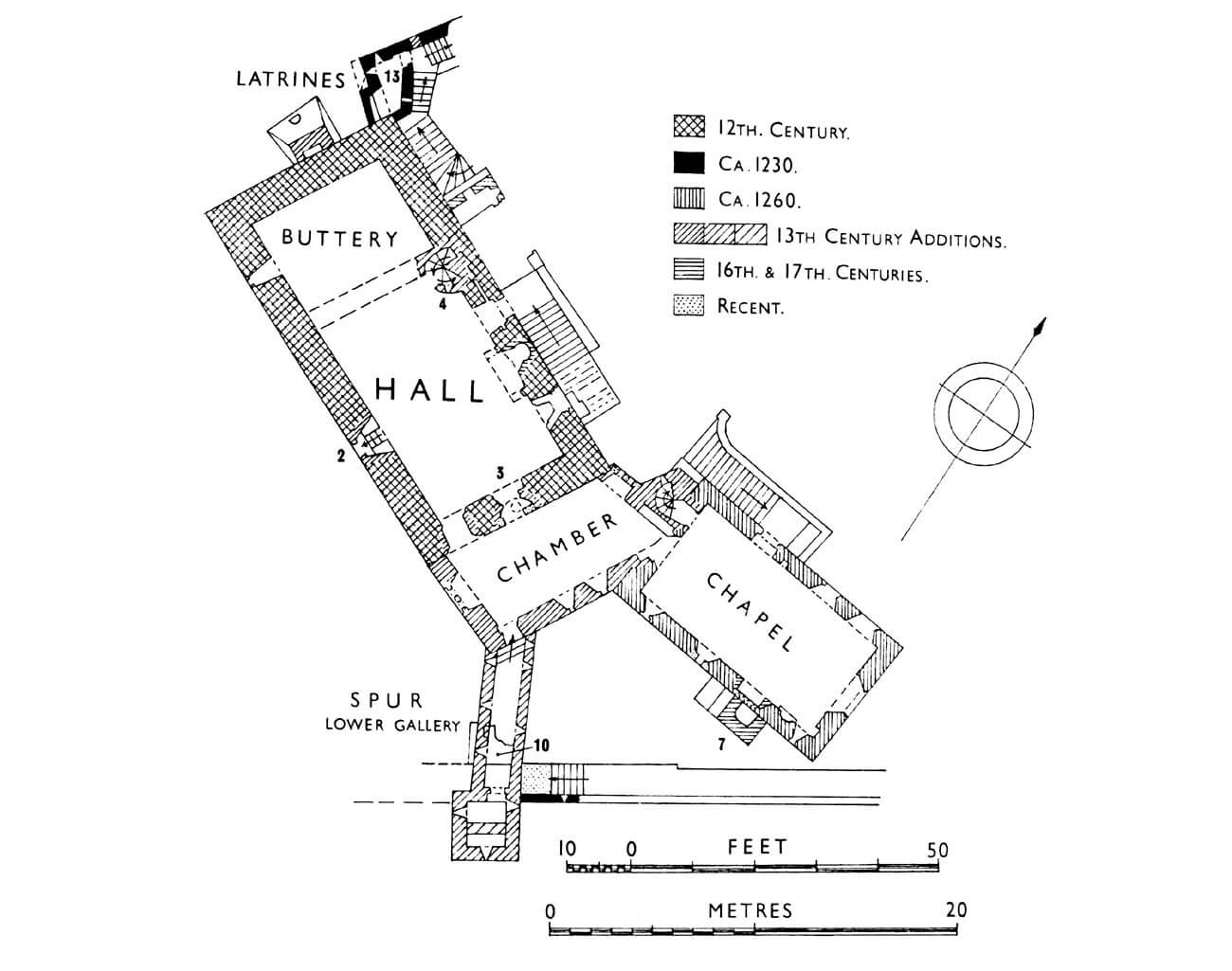

The main, and at the same time the oldest residential wing from the 12th century, occupied the western part of the courtyard in Manorbier, so it was placed in a typical way, on the opposite side of the gate, in theoretically the safest place in the castle. It was a rectangular, slightly irregular building measuring 20 x 10 meters, with walls not supported by buttresses or a batter. It was not until the 13th century that a buttress-like projection was added from the north-west, the main role of which was to house a latrine. The defensive walls of the castle, built at the same time, were added to the building in the north-west and south-east corners, so that two walls of the house, one longer and one shorter, formed part of the defensive perimeter. For this reason, a wall-walk operated in the crown, hidden behind a battlemented parapet. It surrounded a roof tilted at a considerable angle, devoid of stone gables. The entire structure with massive walls around the entire perimeter, battlements and small and sparse windows, was characterized by significant defensive values, placed above living comfort. This was partly due to the fact that in the 12th century the building apart from the eastern tower was the only stone part of the castle. However, the expansion of the fortifications in the 13th century weakened the military importance of the house and resulted in its partial transformation.

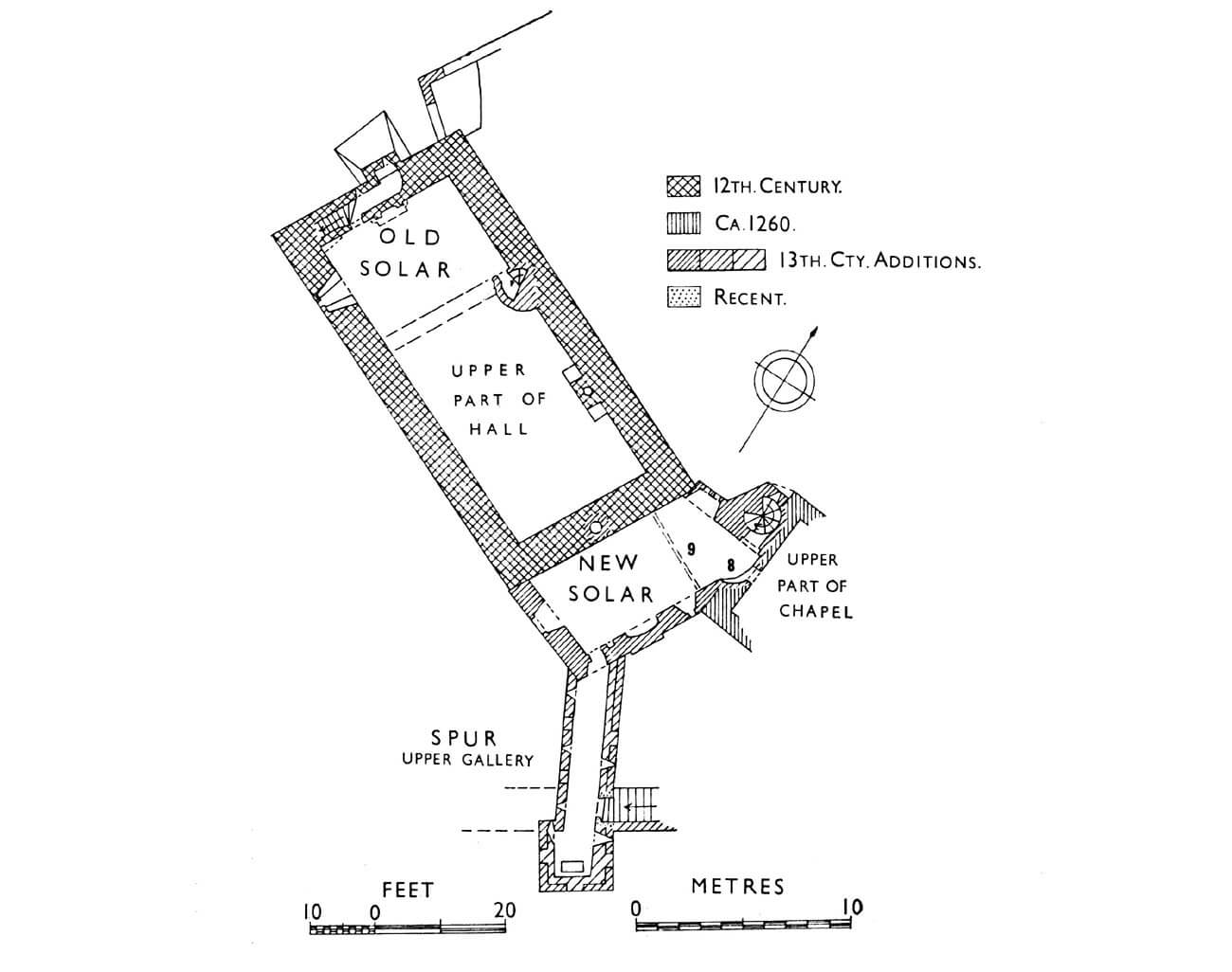

Inside, on the first floor of the building there was a representative great hall, and on the ground floor a storage space. The ground floor was divided by a wall separating a smaller chamber on the western side and a larger eastern room. Both were completely dark, without windows, initially with the only entrance from the courtyard and covered with flat ceilings. The great hall on the first floor occupied the central and eastern parts of the building. It was a place for eating meals, organizing feasts, holding courts or entertaining guests, constituting the most representative place in the castle. It was heated by a fireplace, and a large part was probably occupied by a lord’s table, located closer to the eastern side. The entrance led directly from the courtyard, via wooden stairs, through a door blocked with a bar pushed into an opening in the wall. Initially, the hall was lit by very small windows, enlarged only in the 13th century. It was probably then that a spiral staircase was inserted into the interior, connecting three floors, partially embedded in the wall and unusually lit by a slit directed to the interior of the hall. From the west, the hall was adjacent to a low buttery, lit only by a single slit opening. On the second floor in the western part of the building, above the buttery ceiling, there was an additional private chamber of the lord of the castle. It was also heated by a fireplace, lit by a single window with a stone seat and equipped with a narrow passage in the thickness of the north-western wall, leading to a latrine in the buttress and to the upper defensive gallery.

Around 1260, a chapel measuring 10.7 x 5.2 metres was added to the north-eastern corner of the hall, situated at a slightly unusual angle, which resulted in a narrow courtyard in the corner of the castle. The sacral part was located on its upper floor, where it was accessible via external stairs from the courtyard. The interior of the chapel was vaulted with a high pointed barrel, tiled on the floor, plastered and covered with wall polychromes. A piscina, a stone stoup and pointed sedilia were placed in its walls. The arrangement of the windows was slightly irregular, but traditionally the largest one was placed on the axis of the eastern wall. Most of windows had moulded archivolts and cornices, and some had corner shafts with capitals covered with plant bas-reliefs. The eastern window was filled with tracery. Below the chapel there was a room heated by a fireplace and lit by lancet windows, covered secondarily, but probably still in the Middle Ages, with a barrel vault. It may have been an auxiliary kitchen or a kind of secular calefactory.

Shortly after the chapel was built, the space between it and the hall was filled with a vaulted passage leading to the Water Gate and further on to the seaside port. The gate was 1.4 meters wide, with a door closed with a bar set into an opening in the wall. No other security measures were created, so according to 13th-century standards the rear entrance was poorly protected. Above the passage, a storey was created, occupied by a single room, heated by a fireplace located in the former window recess of the hall. Higher up, on the second floor, there was also a comfortable living chamber. Both floors above the gate were lit by large two-light windows, while the wall of the building was not equipped with battlements in this section. The living quarters were connected by vaulted galleries in the wall with a slender latrine turret protruding beyond the perimeter. The upper chamber was also connected to the western end of the chapel, where the matroneum was located. The interior of the upper chamber was divided in the Middle Ages by a wooden screen, separating the main part from the vestibule by the spiral staircase, set in the thickness of the wall at the junction with the chapel. The upper chamber was heated by a fireplace, next to which a wall niche was created, perhaps intended for a candle for people going to the latrine.

In the north-western part of the courtyard, since the 13th century there was a long building, attached to the inner elevation of the defensive wall, thickened at that time to allow for supporting of the roof. In its ground floor there were three window niches with stone seats on the sides, providing access to shutters closed with latches. Near the corner, an oven was placed in one of the niches towards the end of the Middle Ages, which is why this part could have served as a kitchen, especially since there was a well nearby. Another oven and hearth were built in the 16th century on the north-eastern side of the building. The eastern part of the castle courtyard was occupied by a small two-storey building, erected together with the neighbouring curtain wall. Its function was probably connected with the gate situated right next to it. It could have served keepers and guards on duty on the walls. The southern part of the courtyard could have been initially empty or blocked by lighter buildings. The rectangular utility building by the long curtain was erected at the earliest at the beginning of the 16th century.

Current state

bibliography:

Dashwood C., Manorbier Castle, Cardiff 2013.

Kenyon J., The medieval castles of Wales, Cardiff 2010.

King D.J.C., Perks J.C., Manorbier Castle, Pembrokeshire, „Archaeologia Cambrensis”, 119/1970.

Lindsay E., The castles of Wales, London 1998.

Salter M., The castles of South-West Wales, Malvern 1996.