History

The first castle in Llawhaden in the form of a timber-earth defensive circuit (ringwork), was built by the Norman bishop Bernard from nearby St David, at the beginning of the twelfth century. It was a defensive building, but also a center for managing church properties in the region. The castle also provided adequate accommodation for the higher clergy. In 1175, Llawhaden was mentioned in connection with the visit of Gerald of Wales, a monk, chronicler, linguist and writer, who visited his uncle, bishop David Fitz Gerald in the castle. In 1192, Llawhaden was attacked and destroyed by the Welsh of Lord Rhys, which caused a short-term abandonment of the stronghold. When the castle was re-occupied by Anglo–Normans at the beginning of the 13th century, it was extended, in particular by replacing timber fortifications with a stone defensive wall.

At the end of the 13th century, bishop Bek founded a borough in Llawhaden, hoping to increase the economic strength of the settlement and nearby territories. In 1281, he obtained permission from the king for an annual weekly market and two three-day fairs in Llawhaden, and six years later he founded a hospital for the poor. Ultimately, land rents, trade taxes, tolls and income from mills and fisheries made Llawhaden one of the richest estate of the bishops of St Davids. Despite this, the castle itself probably was not significantly expanded by Bek. Even in the first half of the fourteenth century, it was described only as a source of expenses related to its immediate repairs.

A major reconstruction of the castle began in 1362 on the initiative of Bishop Adam de Houghton. Until 1383 the defensive walls were raised, polygonal towers and residential buildings were added, and at the end of the fourteenth century a new gatehouse was built. This work was supervised by construction master John Fawle (Fawley), who in 1383 was appointed by the bishop as constable of Llawhaden. The bishops of St Davids themselves also often stayed in the castle, which was confirmed by the large number of documents they issued there.

At the beginning of the 15th century, the castle was staffed for the last time with a garrison in the face of the Welsh rebellion of Owain Glyndŵr, but at that time it had little military significance and was not besieged by insurgents. Still in the years 1485-1496 it was the favorite seat of Bishop Hugh Pavy, it also served as a bishop’s prison and place of conducting trials. In 1486, parish clerk William ap Hugyn was accused of violating and robbing of a certain Gwenillian, and in 1503 Thomas Wyriott raided the castle to free a woman called Tanglwys detained in it. In the following years of the first half of the 16th century, the castle declined under the rule of Bishop William Barlow, who sold lead from the roofs of the castle to pay for the dowry of one of his daughters. This caused damages to the rest of the buildings and, as a result, it completely fell into ruin.

Architecture

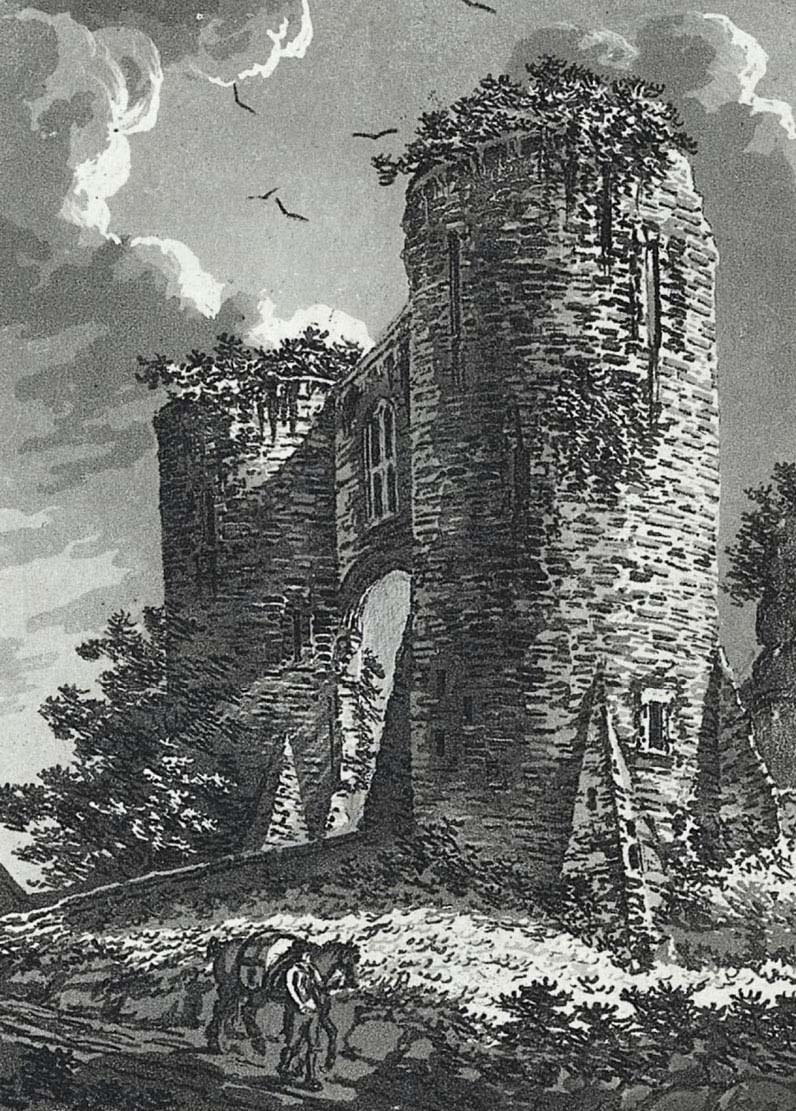

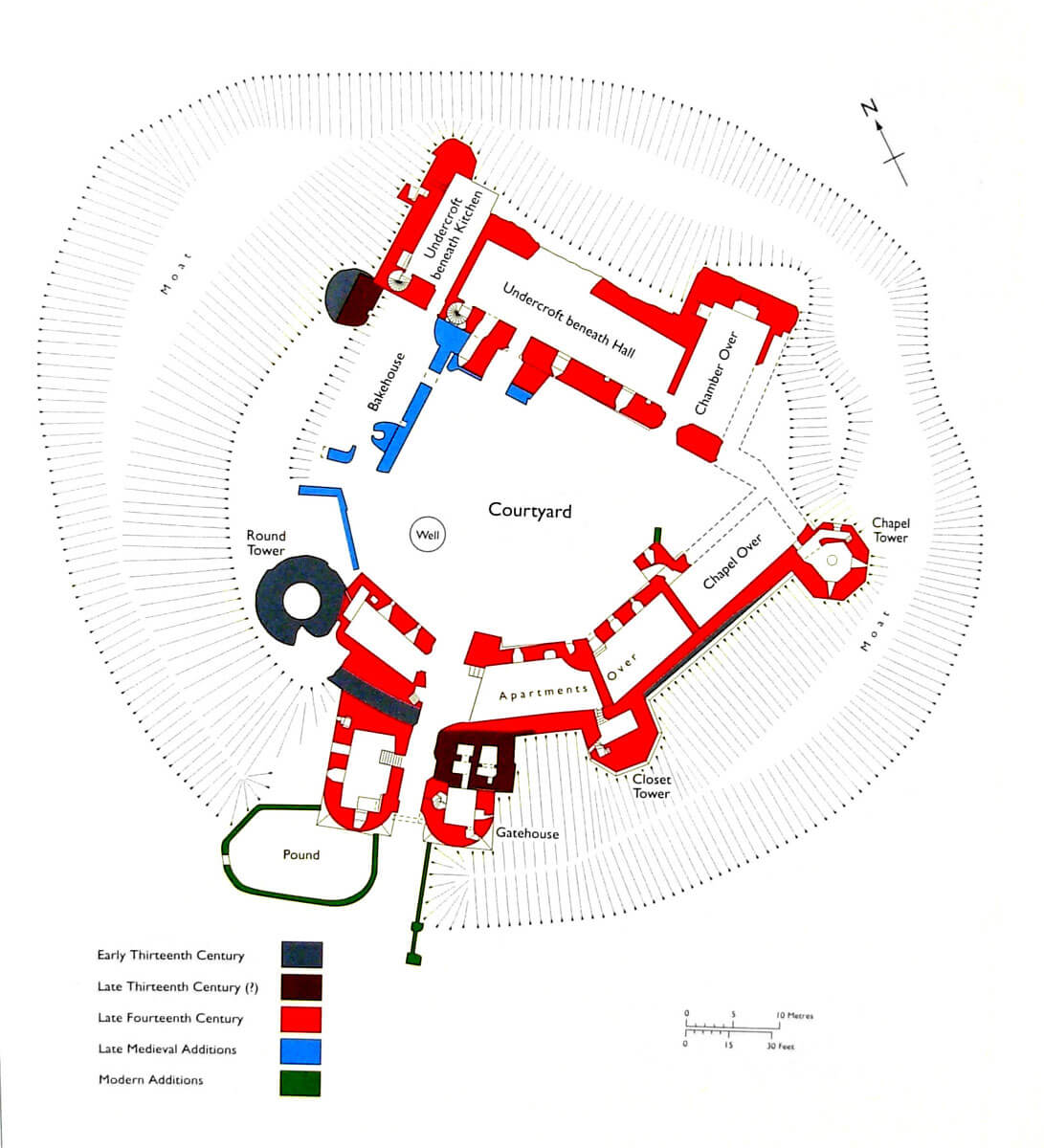

The castle created as a result of a thorough reconstruction from the second half of the 14th century, repeated the roughly oval plan of the earlier defensive circuit and used an older dry moat (ditch) surrounding the whole stronghold. The entrance was from the south-west side and ran through a drawbridge and gatehouse from the end of the 14th century. It was a typical construction for Wales (Carmarthen, Kidwelly) at the time, consisting of two horseshoe flanking towers, reinforced with solid spurs at the ground floor and topped with a battlement, and perhaps machicolation above the centrally located entrance. The road to it led through a wooden drawbridge, over the ditch. Inside, additional protection was provided by a portcullis, door and arrowslits, including the so-called murder holes in the gate passage vault. Despite this, due to the late date of erection, the gatehouse was more a representative building than a hard to capture obstacle. This is especially demonstrated by large, trefoil windows in external facades. The gate also provided good housing conditions, having several vaulted chambers warmed by fireplaces and illuminated by large windows with stone benches on the sides. In its eastern back side, an older, four-sided tower from the 13th century was incorporated, in which latrines were placed.

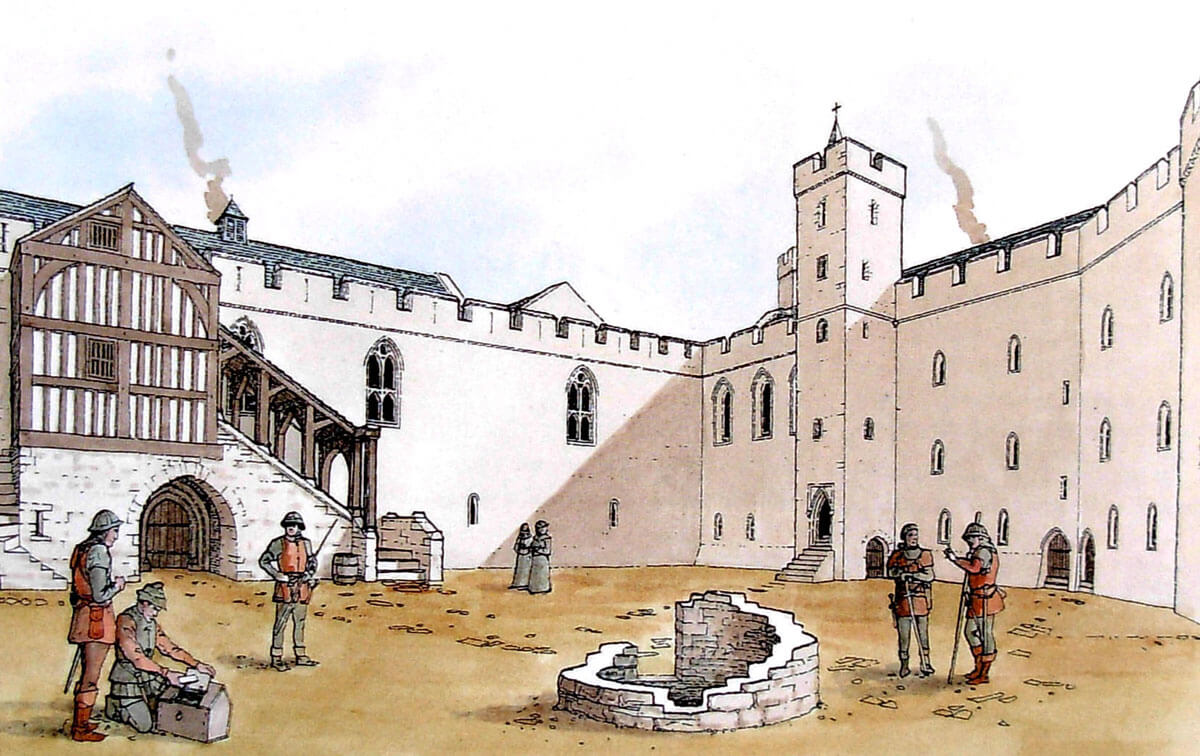

Housing and representative conditions at the castle were provided by the northern wing in the shape of an elongated quadrangle with two projections facing towards the ditch on the north-east side. In the ground floor it housed warehouses and pantries placed in one large room with a barrel vault, and on the first floor there was a centrally located great hall, flanked by the kitchen and the service room on the west side, and the bishop’s private chamber on the east side. The latter was illuminated from the north with a large window overlooking the castle gardens, flanked by two small antechambers with latrines, placed in the thickness of the walls. Internal communication was provided by spiral staircases formed in the thickness of the perimeter walls. The grat hall had impressive dimensions of 24 x 7 meters. It was used to make feasts and parties, meet guests and hold important appointments. The entrance to it led through an external, stone – timber staircase leading from the courtyard to the first floor. Initially, access to it began on the left side, but after building the neighboring bakery it was blocked and moved to the right side. The main portal at ground level was in the form of a triple chamfered ogival portal and was located below the stairs to the first floor. A wooden door was embedded in it with iron hinges, locked from the inside by a bar.

On the west side of the courtyard there was a 30 meters deep well and a bakery building from the end of the 15th century. Next to it, a late-medieval building with a vaulted basement was attached to the perimeter wall, probably serving as the seat of the castle garrison.

The southern and eastern side of the courtyard was occupied by a series of slightly angled buildings adjacent to the defensive wall. They could have been crowned with a battlement and a defensive gallery with arranged gargoyles for draining excess rainwater. Above the vaulted ground floor of economic functions they housed episcopal chambers and guest chambers, placed in two rooms on the first floor and two on the second floor, and a chapel. All the chambers were equipped with fireplaces, and the main windows were opened from the courtyard side. Communication between them was provided by a staircase in the middle of the range. The main entrance to south wing was in a tall, slender, five-story vestibule, whose entrance portal was flanked by two carved heads, perhaps representing the patrons of Bishop Adam Houghton: John of Gaunt and his wife Blenche. Inside the vestibule, a curving staircase led to the chapel, in front of which was a rib vault falling to the corner shafts. On the highest three floors of the vestibule there were small, square chambers, and vertical communication was provided there by a smaller spiral staircase. The highest chamber had windows in each wall and a vault. Stairs led from it even higher to the roof, perhaps topped with a spire. It was the highest element of the castle from which there was a view of the entire area. The chapel was on the first floor, in the eastern part of the building, next to the polygonal eastern tower. From the side of the courtyard, it was illuminated by three large pointed windows and a similar series of windows pierced in the external facade. Its interior was probably covered with wall polychromes.

In the basement of the eastern tower (Chapel Tower) there was a prison, and in the ground floor (accessible from the courtyard) a polygonal chamber. Entrance to the unlit prison cell was only possible through a hatch in the ground floor, while from the ground floor chamber a narrow corridor in the thickness of the wall allowed access to the small latrine. The chamber on the first floor of the tower could serve as a priest’s apartment, as there was a fireplace and a latrine, or a sacristy of the chapel. Access to it was possible from the level of the back of the adjacent chapel. On the even higher floor of the tower was another room, probably serving administrative purposes or as a treasury. Its polygonal interior was crowned with a groin vault. It was accessible through a staircase and a passage in the wall thickness, independent of the lower chapel. The passage could also lead from it along a short section of the perimeter wall to the bishop’s private chamber in the north range. The eastern tower was strongly protruted in front of the defensive perimeter towards the ditch, as was the southern polygonal tower called Latrine or Closet Tower. In addition to the function indicated by its name, it also had small sleeping chambers, located in the rear, closer to the courtyard side of the tower. In the front side there were latrine outlets directed towards the moat, but what is interesting, no arrowslit was pierced from the front, which indicates the weak interest of builders in the defensive function. In total, a large number of latrines in the castle pointed to the growing importance of hygiene in the late medieval period, while numerous small chambers warmed by fireplaces filled the increasing demand for privacy and comfort, remaining in contrast to the large, single common chambers dominating most of the Middle Ages.

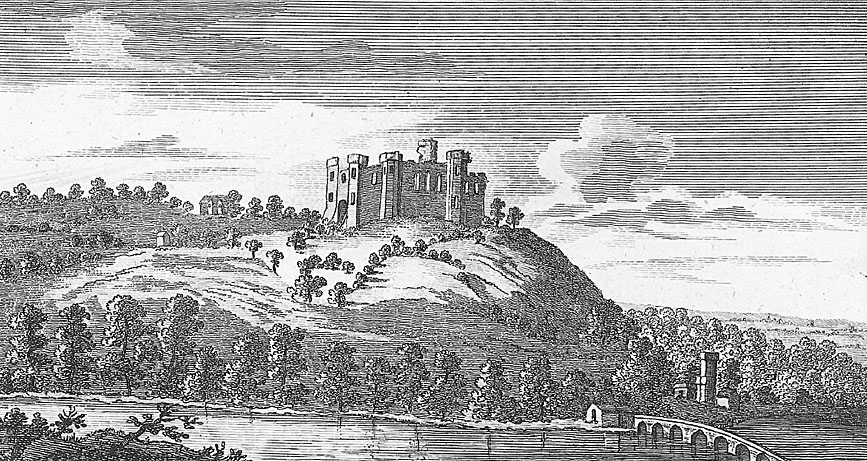

Current state

The castle has survived to modern times in the form of an advanced ruin. The southern range with two polygonal towers and a five-story vestibule have been preserved in the best condition. A characteristic element of the castle is the partly preserved, external wall of the main castle gatehouse from the end of the 14th century. The northern range is in a worse condition, although its lower parts are visible, including entrance portals and some windows. The north-western part of the castle was the least fortunate, after which a defensive wall, a cylindrical tower from the 13th century and a bakery building from the 15th century only provide foundations. The castle is managed by the governmental agency Cadw and made available for free for sightseeing.

bibliography:

Kenyon J., The medieval castles of Wales, Cardiff 2010.

Lindsay E., The castles of Wales, London 1998.

Salter M., The castles of South-West Wales, Malvern 1996.

Turner R., Lamphey Bishop’s Palace, Llawhaden Castle, Cardiff 2000.