History

The beginnings of the church in Llantwit Major (Welsh: Llan Illtyd Fawr) according to unconfirmed tradition date back to the early 5th century. A college of monks or scholars called Caer Worgorn was supposed to have been established in the settlement at that time, but was raided and burned down several decades later by Irish pirates. According to more credible accounts, Saint Illtyd settled in Llantwit at the end of the 5th or beginning of the 6th century and founded a school and church, considered the oldest centre of learning in Britain. According to tradition, many Celtic saints studied at the monastery, including Saint David, Saint Samson, Saint Paul Aurelian, Saint Tudwal, Saint Baglan and King Maelgwn of Gwynedd. Moreover, priests educated at Llantwit founded further temples throughout southern Wales and England. In 987, the monastery was attacked by the Danes, but after being rebuilt, the school continued to function until the Anglo-Norman invasion in the 11th century. When Robert Fitzhamon occupied the land, part of the endowment of Llantwit was transferred to the English abbey at Tewkesbury, and the wooden buildings of the college and the church were destroyed during the conquest.

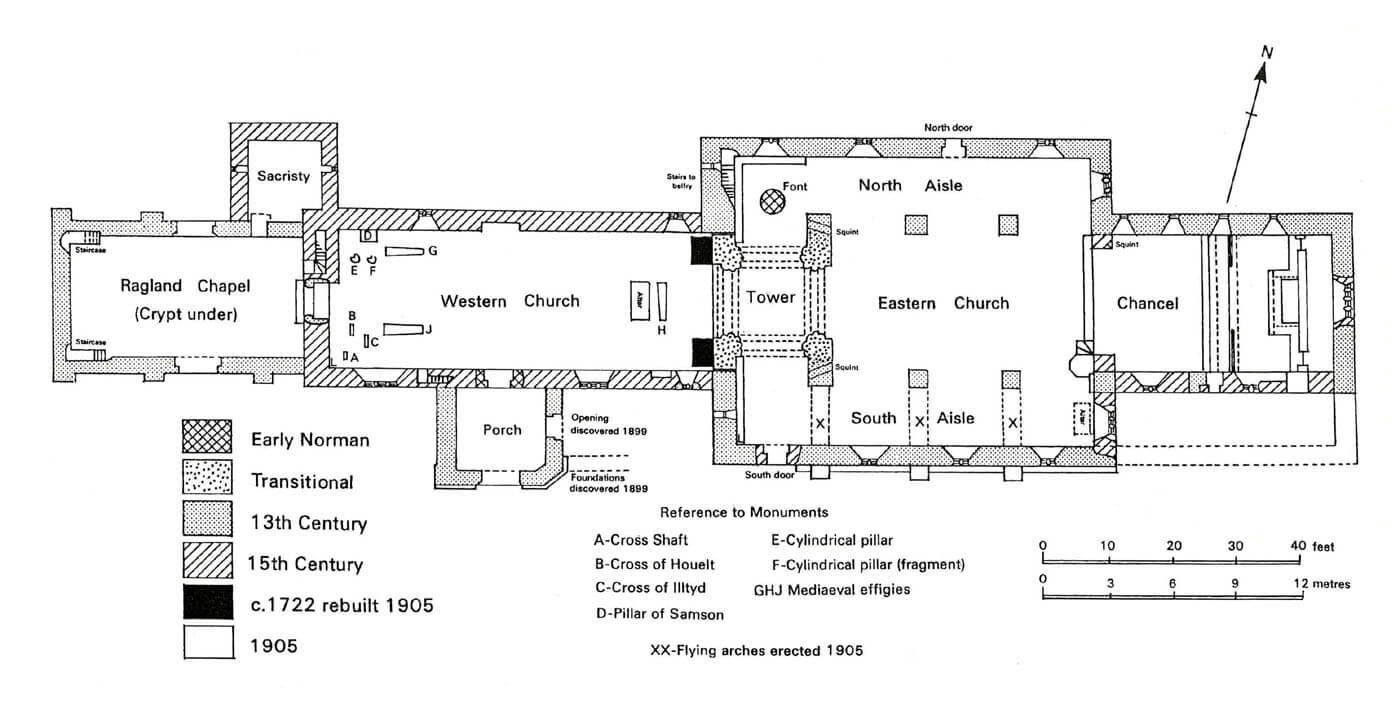

In the early 12th century, the Anglo-Normans built a parish church on the ruins of the old buildings. The former college or monastic community may have continued to function, but it had lost its importance. It was probably also under the control of the abbot of Tewkesbury. In the 13th century, the Romanesque church underwent a major expansion. First, an early Gothic tower was added, and then a second nave on the eastern side of the original church, which was used by the monastic community. The older church was used exclusively as a parish from then on. During the second stage of work in the late 13th century, builders probably struggling with financial problems, as it was carried out using much simpler decorative solutions. Perhaps due to the less skilled construction workshop, there were also structural problems with the statics of the eastern part of the church.

In the 14th century, construction works on St. Illtyd’s church came to a stagnation, probably caused by the building having already reached its optimum size in the previous century. No significant architectural investments were made in Llantwit Major until the end of the 14th century. It was not until the beginning of the 15th century that the oldest part of the church was thoroughly rebuilt using older architectural details and enlarged with a sacristy with a living room. Construction works were also carried out on the eastern part of the church at that time, where the fittings (altars) and architectural details (window frames, chancel arcade) were replaced with late Gothic ones and the church’s interior was adapted to changing tastes (wall paintings).

In the 16th century, as a result of the reformation efforts of King Henry VIII, the monastic community of Llantwit was dissolved and the eastern part of the church was taken by the parish. The medieval monastic farmstead fell into ruin, most of the income was lost, and many elements of the equipment and decoration were destroyed. The western chapel of the church ceased to be used and served mainly as a warehouse, eventually being abandoned and falling into ruin. The remaining parts of the church were in better condition, although it also fell into decline until the 18th century, and around 1731 the tower had to be supported by early modern buttresses. Serious renovation work on the historic building began at the end of the 19th century and continued at the beginning of the 20th century.

Architecture

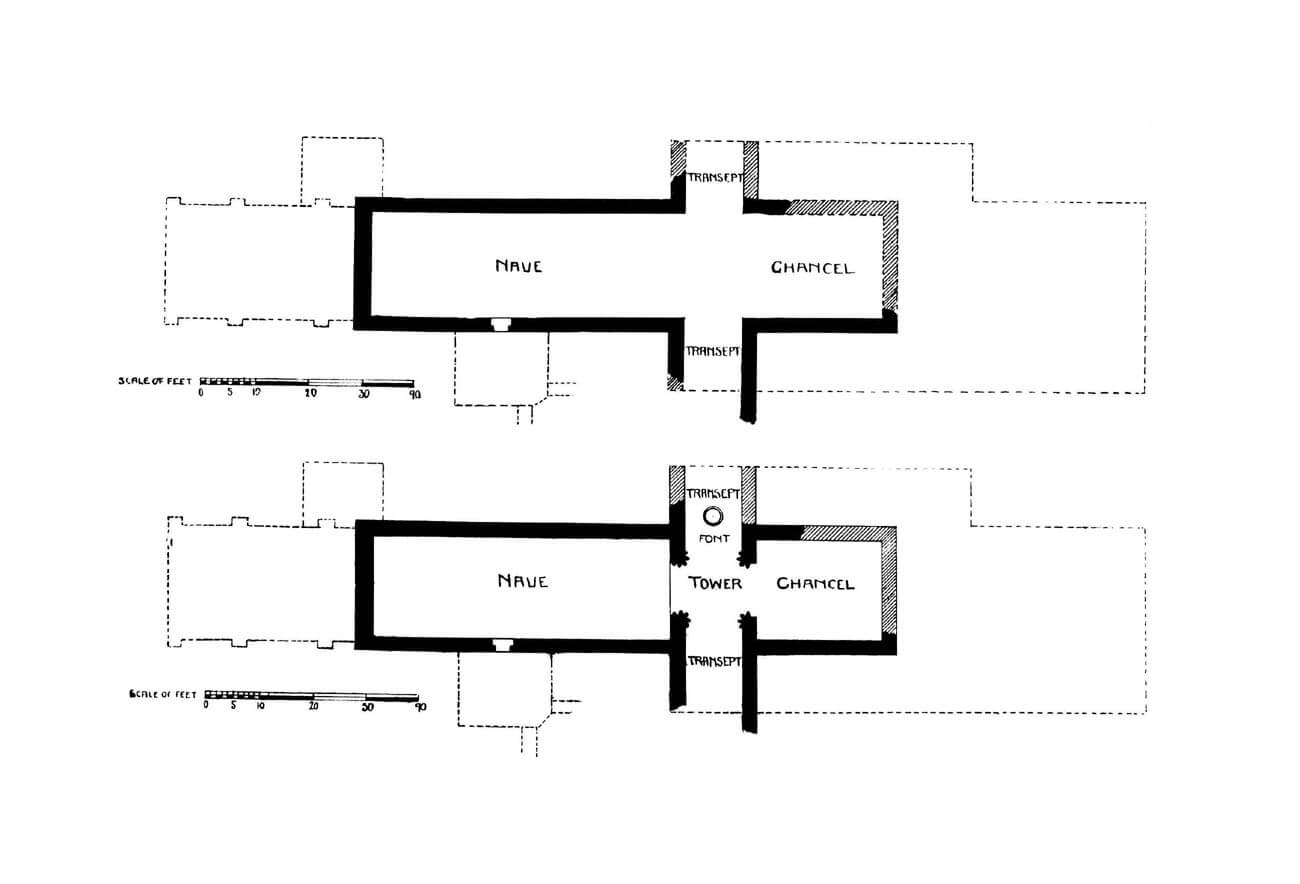

The Romanesque parish church from the beginning of the 12th century was located in the western part of the settlement, on the eastern side of the meridianally flowing stream. It originally consisted of a rectangular nave 12 meters long (later the so-called Western Church), connected to the east with a short transept and chancel. The chancel was the same width as the nave, and in the east it was probably straight ended. The entrance to the interior of the nave led from the south, through a very simple, unmoulded, semicircular portal. In addition, in the 13th century, a new entrance portal was placed in the Romanesque nave from the west, perhaps on the site of a more modest older one. The original windows of the church were probably very narrow and splayed, probably like the southern portal semicircular.

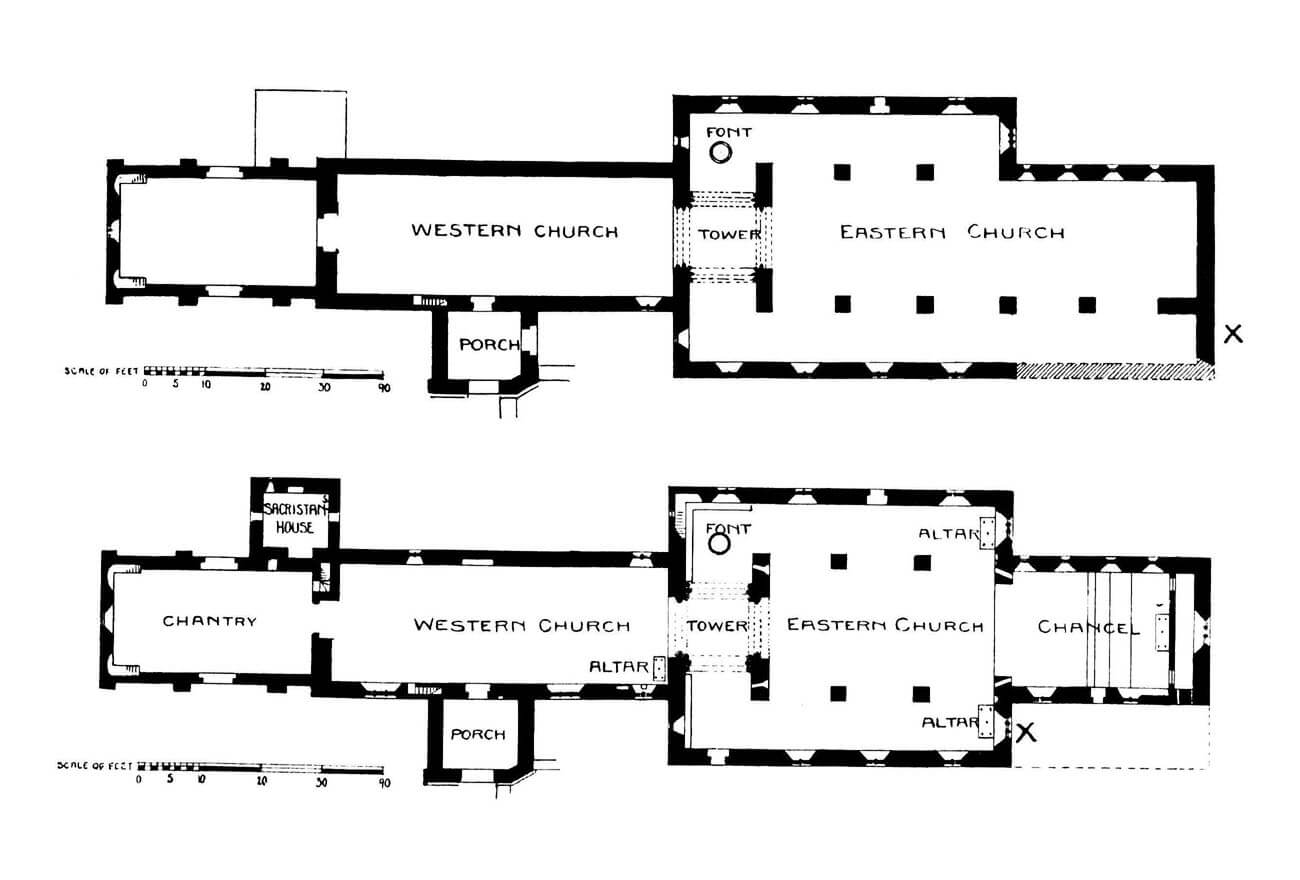

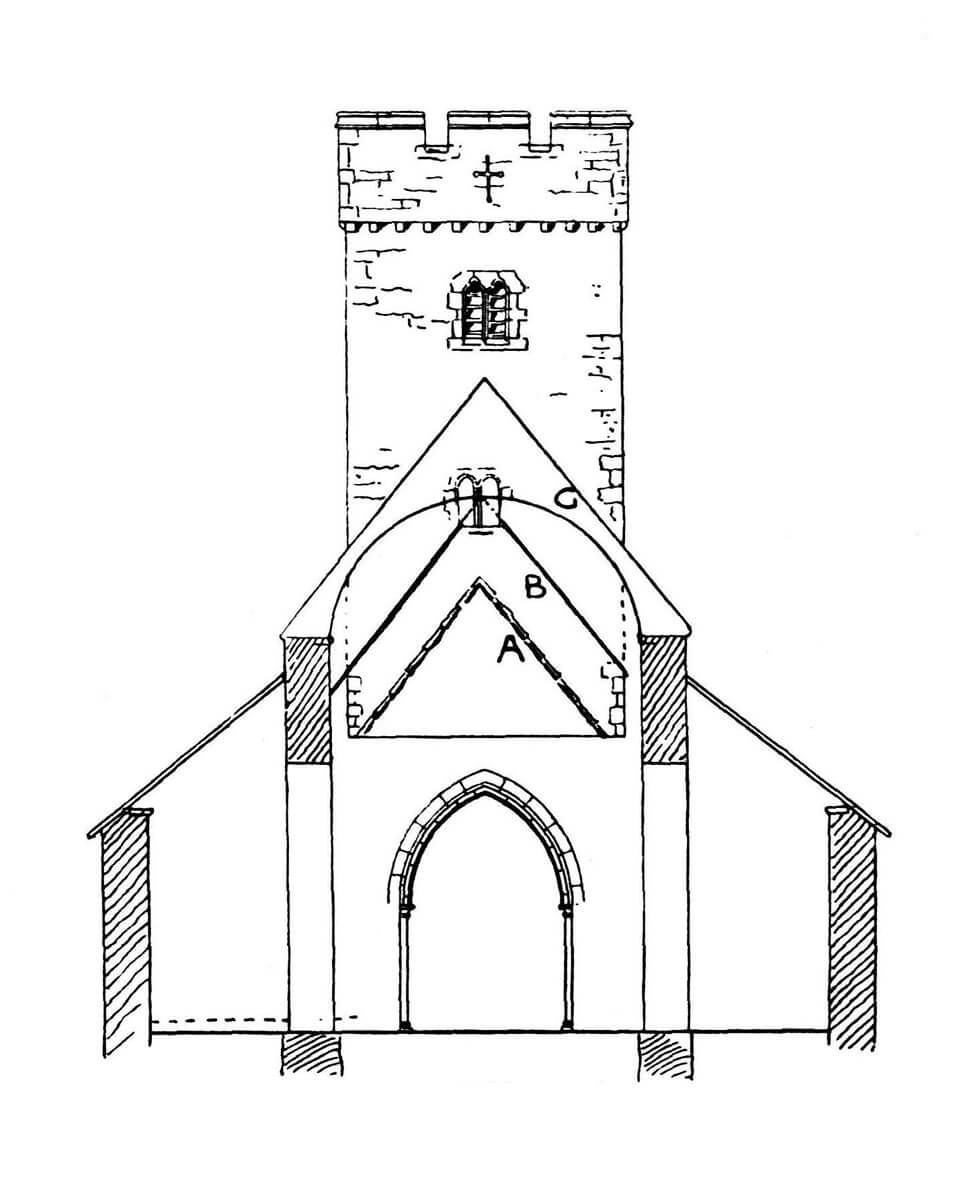

During the construction works at the beginning of the 13th century, the church of St. Illtyd was enlarged by the insertion of a quadrangular, originally relatively low tower at the crossing. Its ground floor was made of four massive, richly shaped piers, between which chamfered pointed arcades were spread on semi-columns with smooth and bas-relief capitals. The tower structure was placed next to the older walls of the church, but it was not connected to them and had no supports that could take the pressure of the arches on the eastern and western sides in the ground floor, which over time, after the tower was raised, led to its problems with statics. In terms of plan, the layout of the church after the reconstruction remained without major changes, because the early Gothic tower was flanked from the north and south by a Romanesque transept, and from the east it was adjacent to a Romanesque chancel on a rectangular plan, probably used by the monastic community. The Romanesque nave, on the other hand, functioned as a parish church, enlarged in the 13th century from the south by a large two-story porch, to which a small annex was added on the eastern side at an unknown date.

In the late 13th century, a rectangular Lady Chapel, also known as the Galilean Chapel was added to the Romanesque nave on the west side. It was supported by buttresses on the outside, while inside, stairs in its two western corners led to the gallery. Large portals with pointed arches were placed in the middle of the northern and southern walls of the chapel, placed exactly opposite each other. It were probably used for processional purposes, while the most important people could have looked on from the gallery. The liturgy could also have been celebrated in the gallery, as an altar niche and a piscina were created there in the wall. A similar, wooden gallery could also have been located in the eastern part of the chapel, where appropriate corbels were placed. Possibly both galleries were connected or there was one upper storey, but in this case the doors would have had to fill only the lower part of the entrance portals, as their archivolts exceeded the level of the galleries.

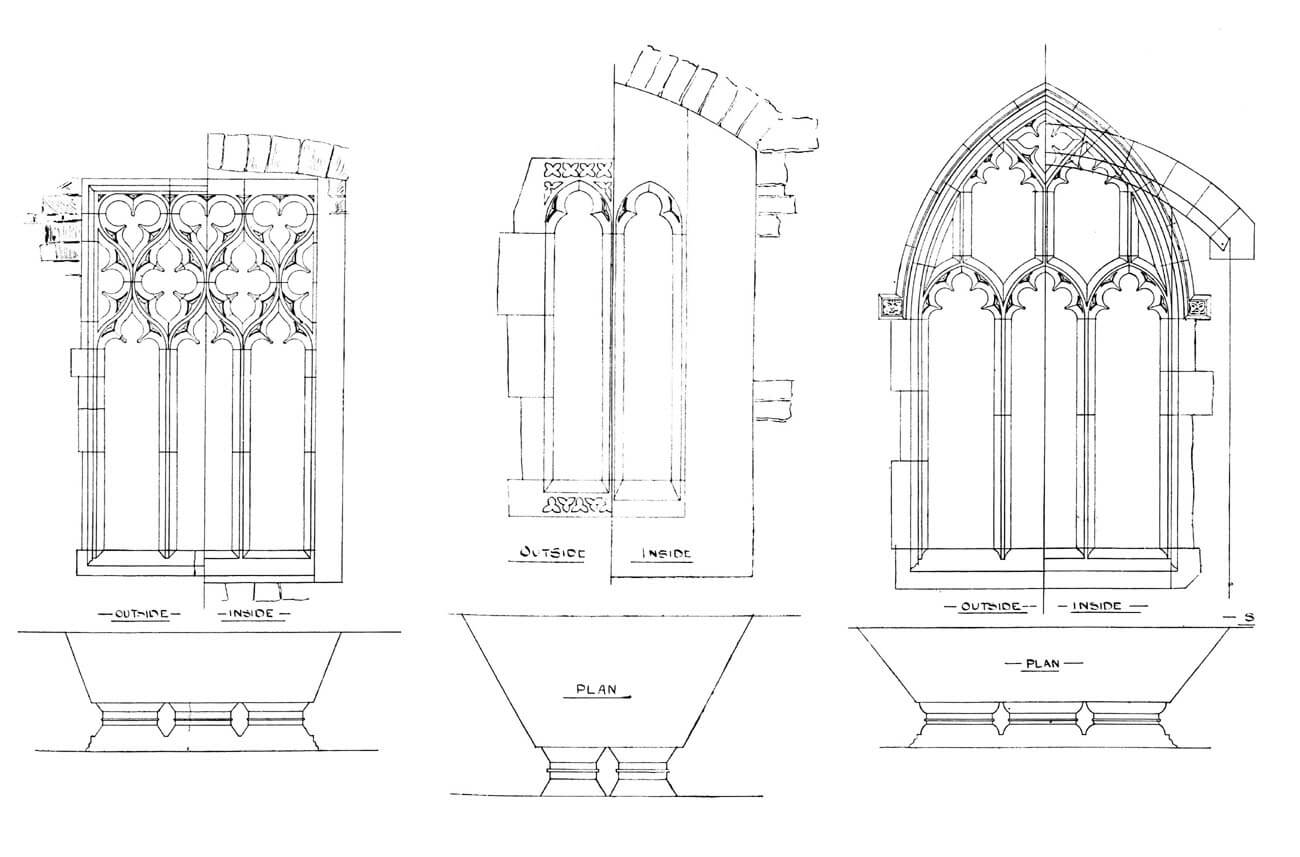

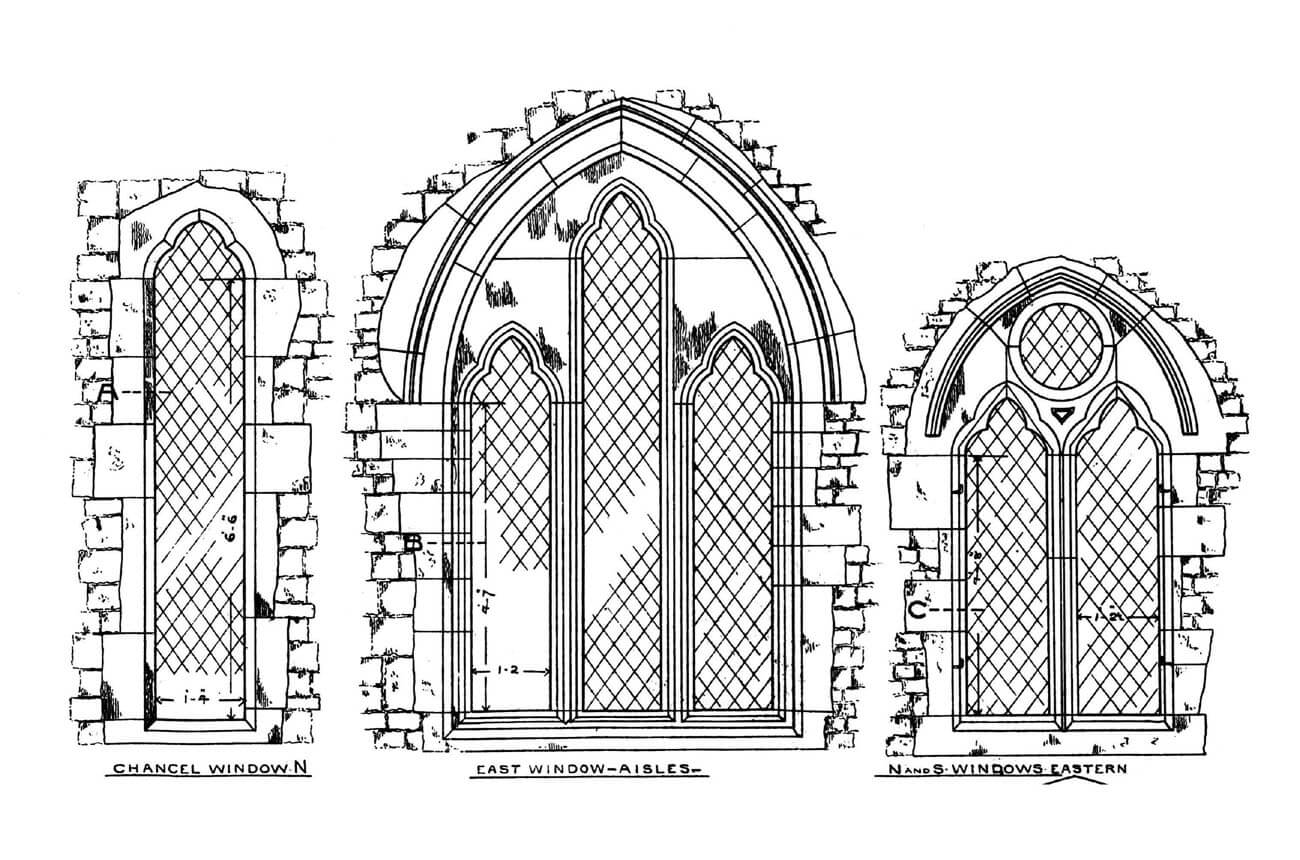

At the end of the 13th century, the Romanesque transept of the church was absorbed by the aisles of the pseudo-basilica nave that was built at that time, ending in the east with a new chancel built on a rectangular plan. As a result, the tower incorporated into the nave became the central part of a greatly elongated and unusual building. The eastern part of the church had central nave and two aisles separated by quadrangular pillars and pointed arcades without moulding, much more primitive than the older arcades under the tower. The pillars of the arcades followed the lines of the original Romanesque walls, with those on the southern side built exactly on the old foundations. The proportions of the building were characterized by a large width of the central nave and a relatively short length, which could have resulted from the limited space for expansion. The central nave and northern aisle were created as four-bay, but the southern aisle was initially two bays longer and reached the end of the chancel. The aisles were closed from the east and west by straight walls and lit by pointed windows with trefoil-shaped traceries: three two-light windows from the north, three two-light windows from the south and single three-light windows from the east. From the west, the aisles were lit by small single-light openings. The central nave, although it gained the greatest height, was lit only indirectly, by the windows of the aisles. Two pointed entrance portals were also created in the walls of the Eastern Church: in the third bay from the north and in the first western bay from the south, but the latter being inserted in place of the window only in the 14th or 15th century. The chancel was lit by single-light windows with slightly outlined trefoil heads; only in the eastern wall could there have been a larger opening or a triad of narrower windows characteristic of monastery churches.

At the beginning of the 15th century, the walls of the Romanesque nave were thoroughly rebuilt, or in some places it were built from scratch on the original foundations, using two older portals. Then a roof truss made of Irish bog oak was installed and a square annex with a sacristy was added to the nave from the north, located at the junction with the Lady Chapel. It consisted of two main rooms, one on the ground floor and the other on the first floor, above which there was an attic under the gable roof. Therefore, the rebuilding also led to the widening of the western wall of the old nave, located on the extension of the eastern wall of the annex, in the thickness of which the stairs to the sacristy upper floor were placed. The lower room of the annex was lit by two small windows and connected to the chapel. The upper room housed a large fireplace and was lit from three sides, so it had to serve a residential function.

At the beginning of the 15th century, the roof of the central nave of the Eastern Church and the tower were raised, and a Gothic arcade with a pointed, unmoulded archivolt was inserted between the central nave and the chancel. Perhaps because of its insertion, the southern aisle was shortened, from then on equal in length to the northern aisle. Above the chancel arcade, a beam was placed on four corbels, and the wall was covered with a painting with a checkerboard pattern, constituting a background for the sculptures of the Crucifixion (attached to the wall with iron rings). In the Gothic period, the remaining walls of the chancel and the nave, including the pillars between the aisles, were also covered with paintings. In the late Gothic period, the lighting of the chancel of the Eastern Church was changed. From the south, where the original arcades between the aisles were bricked up, new two-light windows were inserted, and between them a pointed portal. The most impressive late Gothic opening was placed on the axis of the eastern wall of the chancel, where a pointed window with a four-light tracery and an archivolt framed by a pointed cornice was set. Four narrow early Gothic windows were left in the northern wall. Interestingly, in the new eastern wall of the shortened southern aisle, an old window was set, transferred from the demolished eastern wall. An attempt to illuminate the central nave of the Eastern Church was made by quadrangular windows with two-light tracery, extending into the roof slope of the aisles.

Current state

St. Illtyd’s Church is one of the oldest and most famous parish churches in Wales, and also the church with the most unique spatial layout, unlike any other Welsh parish churches. It is a building of exceptional importance, both for its history, architecture and state of preservation. Its walls contain architectural details in the Romanesque style (south portal of the West Church), early Gothic style (arcades under the towers, ornate niche of Jesse in the east wall of the south aisle, west portal of the West Church) and high and late Gothic style (windows of the chancel and nave of the East Church, windows of the West Church, piscina in the Lady Chapel). Furthermore, the West Church retains a 15th-century roof truss, while the East Church has wall paintings from the 13th-15th centuries. Among the medieval furnishings, you can see an artfully carved reredos from around 1430, Gothic side altars and a Romanesque font. The church also houses a unique collection of carved stones, tombstones and Celtic crosses from the 9th-10th centuries. In the 21st century, the ruined Lady Chapel was re-roofed, but unfortunately it was decided to leave the gaps in the walls in its longitudinal walls and fill them with glass or rebuilt with a completely different building material.

bibliography:

Corbett J.S., Some notes as to Llantwit Major, „Archaeologia Cambrensis”, 39/1906.

Fryer A.C., Llantwit Major, a fifth century university, London 1893.

Halliday E., Llantwit Major Church, Glamorganshire, „Archaeologia Cambrensis”, 17/1900.

Halliday E., Llantwit Major Church, Glamorganshire, „Archaeologia Cambrensis”, 5/1905.

Rodger J.W., The Ecclesiastical bulidings of Llantwit Major, „Archaeologia Cambrensis”, 39/1906.

Salter M., The old parish churches of Gwent, Glamorgan & Gower, Malvern 2002.

Wooding J., Yates N., A Guide to the churches and chapels of Wales, Cardiff 2011.