History

The first, still wooden, church in Llangennith (Llangenydd) was built by Saint Cenydd (Kenneth) in the 6th century AD. It burned down in 986 during a Danish invasion. In the 11th or early 12th century it was rebuilt, as a stone foundation under the rule of the Norman lords of Gower. The exact date of construction is unknown, but it is known that it was ordained by bishop Herewald, who died in 1104.

Around 1107-1118, Henry de Beaumont donated the church to the Benedictine Abbey in St. Taurin (Evreux) in France. The monks founded a small monastery in Llangennith, which served parishioners and oversaw the estate. In 1218 there were only two or three of them here. The chronicler Gerald of Wales also gave information about the local prior who engaged in an affair with a local woman and remained in the relationship despite numerous admonitions until he was finally deposed. Another information from 1291 recorded in papal Taxatio Ecclesiastica recorded a modest income of the community of just over £ 4 and possession of 120 acres of arable land and six cows.

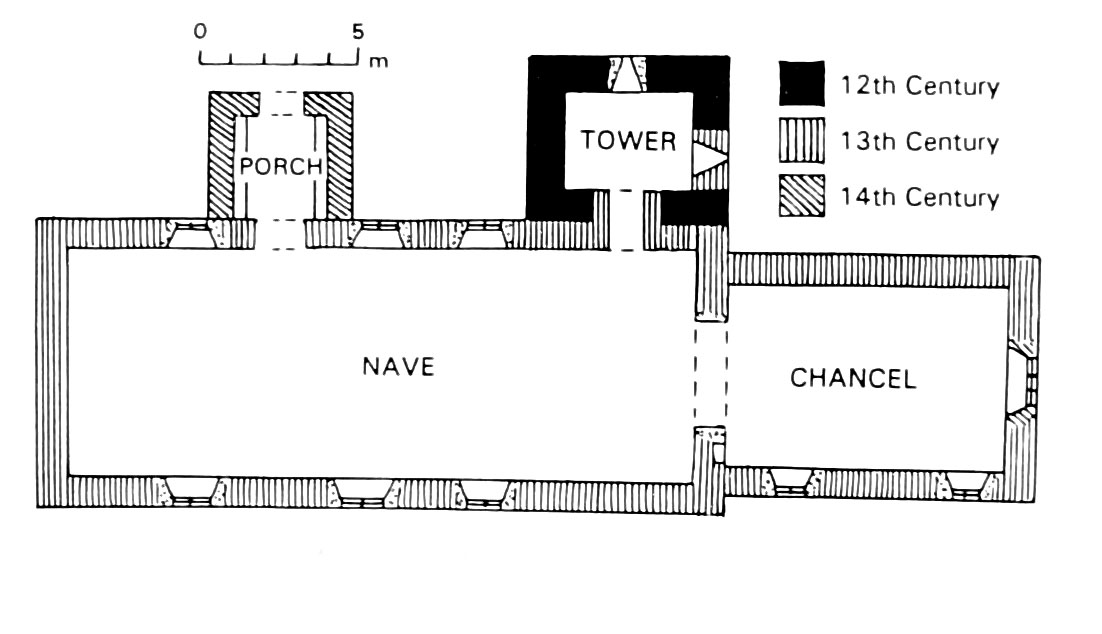

At the beginning of the fourteenth century, the church was significantly rebuilt and enlarged. In 1414, king Henry IV took over all foreign monasteries and then he donated it to Oxford’s All Souls College in 1441, at which it remained until was bought by Major Penrice in 1838. His nephew donated the church to the parish in 1883. In the nineteenth century, a thorough restoration of the building was made.

Architecture

The church from the thirteenth century consisted of a rectangular nave and a rectangular, but much smaller and narrower chancel, also on a rectangular plan. The great church tower was built very unusually, because from the north side at the crossing of the nave and chancel. In the lower part an arcaded wall was made, probably the only remnant of a church from the 12th century or monastic buildings. Probably in the fourteenth century, a porch was added to the north side of the church.

The tower had three floors, narrow lancet windows and a parapet on protruding corbels, topped with a battlement from the north and south. It could have defensive functions, but one can not exclude symbolic meaning or the desire to suspend heavy and large bells, which, with poor quality of mortar, forced construction of a stronger tower. On the other hand, the tower was not supported by any buttresses, only its corners were reinforced with ashlar, that is finely dressed, larger stones compared to the erratics from which the walls were built.

Inside the church, neither the nave nor the chancel were vaulted. Initially, their lighting had to be provided by small, splayed windows, pierced in the chancel from the south and east, and in the nave from the south and north. During the Gothic period, larger pointed windows were introduced into the church architecture. Traditionally, the most impressive form had the eastern window of the chancel, filled with three-light tracery with trefoil and quatrefoil motifs, above which the composition was topped with a single opening, with the shape adjusted to give the whole a pyramidal form.

Current state

St Cenydd’s church in Llangennith is now one of the best-preserved medieval religious buildings in South Wales, and one of the most magnificent rural temples, distinguished by its large size and massive tower. Inside there is a 14th-century tombstone of a knight from the de la Mare family, and a fragment of a 9th-century cross at the western wall. Unfortunately, most of the windows and portals were renewed or replaced during the Victorian renovations. The exception is the eastern window on the ground floor of the tower, moreover, the eastern window of the chancel may come from the Gothic period.

bibliography:

Burton J., Stöber K., Abbeys and Priories of Medieval Wales, Chippenham 2015.

Gregor G., Toft L., The churches and chapels of Gower, Swansea 2007.

Salter M., Abbeys, priories and cathedrals of Wales, Malvern 2012.

Salter M., The old parish churches of Gwent, Glamorgan & Gower, Malvern 2002.