History

Cistercian Cymer Abbey in Llanelltyd was founded in 1198-1199, under the patronage of Maredudd ap Cynan ab Owain Gwynedd, ruler of Merioneth, and his brother, Gruffudd ap Cynan, prince of North Wales. The first buildings of the abbey may have been of wooden construction, but construction of a stone church and claustrum quarters began in the early 13th century. The initial plans were ambitious, but the monastery church with typical Cistercian layout was never completed, and a somewhat simpler and smaller church had to be made.

Like other Cistercian abbeys in Wales, sheep and horses were bred in Cymer, delivered to the court of Llywelyn ap Iorwerth (Llywelyn the Great or Llywelyn Fawr). The trade was facilitated by easy access to the sea, and the income increased the benefits derived from the two nearby rivers. In 1209, Llywelyn additionally granted mining charter, but despite this, the community did not prosper. It lacked arable land and had limited rights to the fishing.

Cymer Abbey was strongly associated with the ruling dynasty of Gwynedd. As a result its buildings were burned during Henry III’s English invasion of 1241. Thanks to strategically advantageous location, the monastery served as a base for Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd’s troops in 1275 and 1279. During the Welsh-English conflict of the 1280s, King Edward I captured Cymer and its farmsteads, but a year later granted compensation of 80 £ for damages caused during the recent wars.

By 1388, the impoverished abbey housed no more than five monks. It likely struggled not only with financial problems but also with a marked decline in religious standards and a deterioration in the discipline. In 1443, John ap Rhys left Cymer and appeared as abbot of the Cistercian abbey of Strata Florida. A certain John Cobbe was elected to replace him, but Rhys had no intention of relinquishing Cymer and exiled his successor. This led to the taking of the community and his new abbot Richard Kirby under royal custody. Once again, the monarch’s supervision was necessary in 1453. During this period, the abbey’s income was valued at a very small amount of £ 15 of annual income.

Despite the royal interventions, disputes over the appointment of the abbot’s office continued at the end of the 15th century. In 1487, there was even excommunication by the general chapter of one of the monks, William, because of his self-proclaimed election. Despite this, in 1491 he was again mentioned in the docuents as abbot of Cymer. Lewis ap Thomas was the last superior of the monastery since 1517. Shortly afterwards, the abbey was dissolved as a result of the edict of Henry VIII, which canceled all monasteries with an income of less than £ 200. Cymer was only making £ 51 a year at the time of dissolution.

Architecture

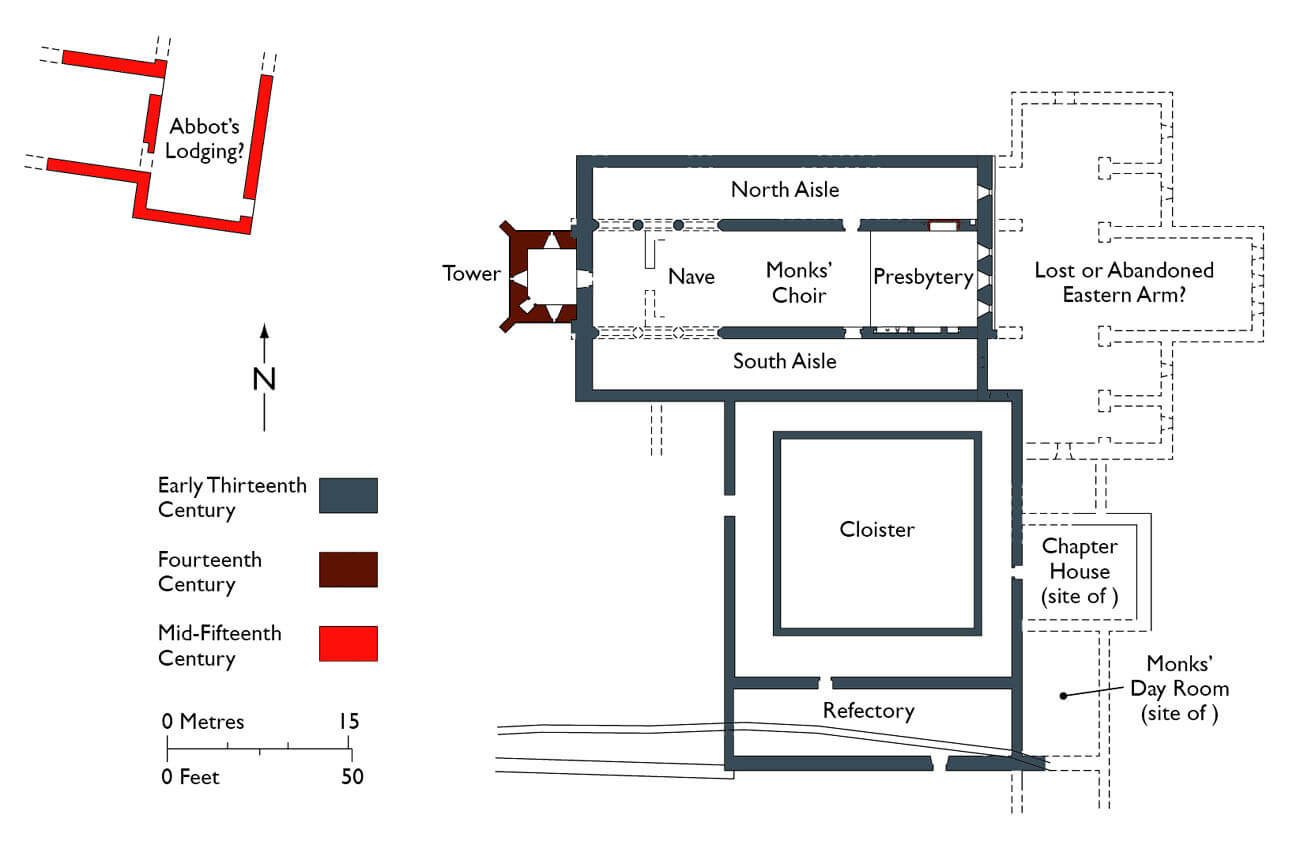

The abbey was built on the eastern bank of the Mawddach River, just near its southwest confluence with the Wnion River. It consisted of the monastery church and the claustrum buildings adjacent to its southern façade, surrounding a quadrangular garth with cloister. The monastery complex also included the abbot’s house, situated somewhat apart on the western side, and a separate economic building. The entire complex was situated at the mouth of a deep valley, bounded by hillsides to the east and west.

The monastery church was a basilica with nave and two aisles on an elongated rectangular plan, without an externally separated chancel. On the eastern side, it was terminated by a straight wall. This unusual layout suggests that the original church design was likely never completed. The northern and southern transepts were never built, while a separate chancel was intended to be located further east. Initially, the church was towerless, but unusually, in the 14th century, a quadrangular tower, reinforced with corner buttresses, was built on the west side. However, the construction of the central tower at the crossing, typical of Cistercian churches, was abandoned.

Lighting in the church came from early Gothic windows with lancet heads and embrasures splayed inward. The eastern wall, pierced by a triad of tall lancets in a pyramidal arrangement (the central window being taller than the two side windows), was a distinctive feature. Above these were three smaller windows, and on the sides were openings illuminating the aisles. A small amount of sunlight must have entered the southern aisle, which adjoined the cloister from the south. The central nave had its own windows pierced in the clerestory, while the northern aisle had windows facing the nearby stream on the north side.

The interior of the church was created in a very unusual way due to the abandonment of the construction of the eastern part of the building and closing the whole with a straight wall at the height of all aisles and central nave (which forced the choir and presbytery to house in the part of the building to be originally only the nave). The western part of the church, intended for lay people, was divided into aisles with two rows of three pointed and moulded arcades, based on octagonal pillars. Behind them, further to the east, a choir of monks began, separated by full walls of the central nave, pierced only by clerestory windows. The monks’ stalls were probably placed along them, and from the west the entrance was separated by a timber rood screen. The eastern part of the central nave was occupied by the chancel with the main altar, accessible by two portals (from the north and south) from the aisles. The latter were, therefore, as if completely separate routes, opened to the rest of the church only in three western bays.

To the eastern part of the south aisle was a square garth, with sides of 22 and 23 meters surrounded by cloisters and monastery buildings. In the eastern wing, according to the Cistercian rule, there was a chapter house, and in the southern range refectory, although its longer axis in this case was quite unusual, because it was based on the east-west line, not north-south. At the corner of the refectory, and the southern end of the east wing, there were latrines, flushed with a nearby stream. They were directly connected to the bedroom – the dormitory on the east wing upper floor. As the abbey was poor and the number of monks was insignificant, the west wing was limited only to the small entrance vestibule connected directly to the cloister.

Current state

To this day, fragments of the early Gothic monastery church remain, along with the lower section of the 14th-century western tower, fragments of the nave and chancel walls, and a row of inter-nave pillars with arcades. Of the claustrum buildings and cloister only the foundations and ground-floor walls remain. The abbot’s house and western outbuilding, although survived to the present day, were extensively rebuilt in the early modern period. The abbey is currently under the care of the Cadw government agency and is open to visitors from 1 April to 31 October, daily from 10:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.

bibliography:

Burton J., Stöber K., Abbeys and Priories of Medieval Wales, Chippenham 2015.

Harrison S., Robinson D.M., Cistercian Cloisters in England and Wales Part I: Essay, “Journal of the British Archaeological Association”, 159/2006.

Haslam R., Orbach J., Voelcker A., The buildings of Wales, Gwynedd, London 2009.

Salter M., Abbeys, priories and cathedrals of Wales, Malvern 2012.

The Royal Commission on The Ancient and Historical Monuments and Constructions in Wales and Monmouthshire. An Inventory of the Ancient Monuments in Wales and Monmouthshire. County of Merioneth, London 1921.