History

According to tradition, the first church in Llandaff was founded at a ford on the River Taff in the second half of the 6th century by Saint Teilo. The construction of the Romanesque cathedral was begun in 1120 by the first Anglo-Norman bishop of Llandaff, Urban, who also wanted to increase the prestige of the church by bringing the relics of the bishop St. Dyfrig (Dubricius). The main construction works on the cathedral were completed under Bishop Nicholas ap Gwrgant, originally a Benedictine monk at Gloucester Abbey, who died in 1183.

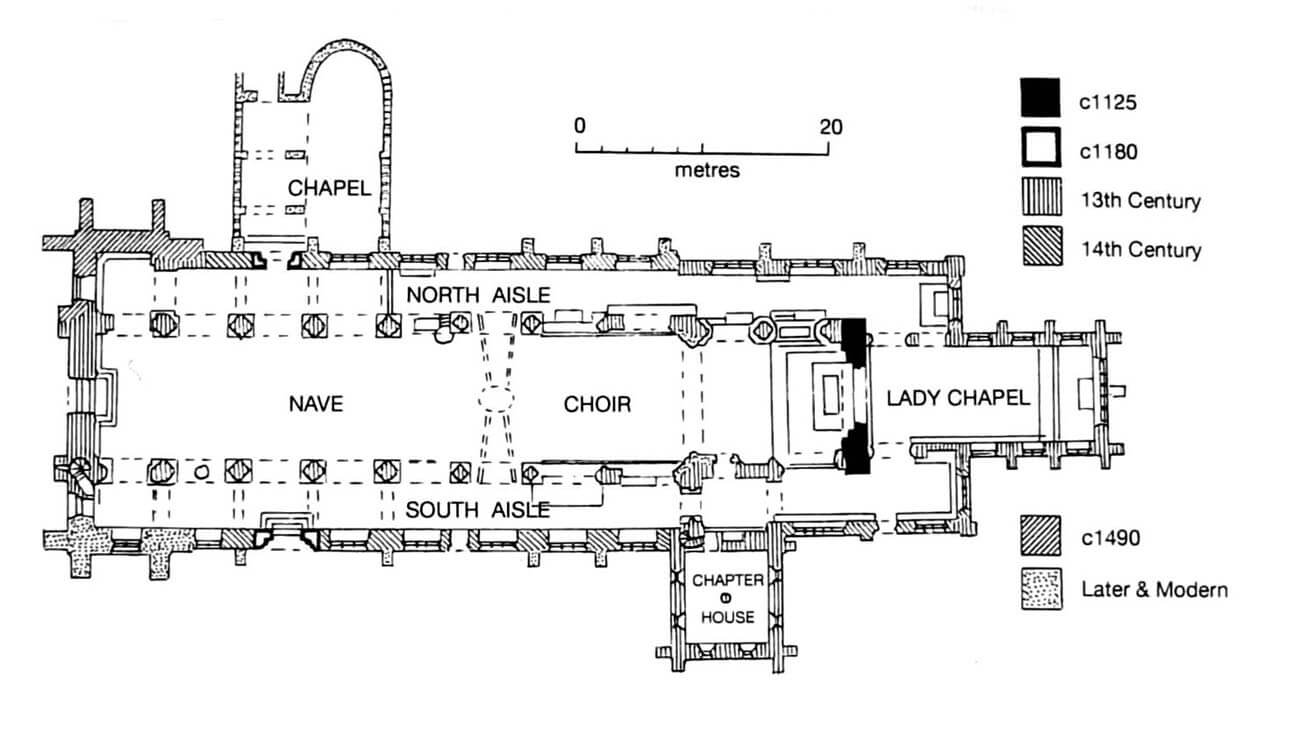

Around 1214, Bishop Henry de Abergavenny organized a cathedral chapter in Llandaff. He appointed fourteen prebends, eight priests, four deacons and two subdeacons, but did not appoint a provost or dean, leaving the administration in his own hands and those of his successors in the episcopal seat. In the time of his successor, William de Goldcliff, a new western façade was built and the nave was rebuilt in the early Gothic style around 1220. In the second half of the 13th century Bishop William de Braose founded the Lady Chapel. As a result, the old chancel from Bishop Urban’s time had to be also rebuilt. It is likely that from that time on, the cathedral was in a state of constant slow repairs and minor alterations. Among others, after the chapel was completed, two bays of the north aisle of the choir were rebuilt, and in the 14th century two side portals were added.

At the beginning of the 15th century, the cathedral was damaged during the Welsh rebellion of Owain Glyndŵr, directed against the rule of King Henry IV and the English administration. Most of the damages were repaired by Bishop John Marshall in the second half of the 15th century, who also purchased new, late Gothic furnishings for the cathedral, including the bishop’s throne and choir stalls for the canons. In 1485, the building was expanded by the addition of the north tower on the west façade, funded by Jasper Tudor, Duke of Bedford, uncle of King Henry VII.

Until the early 16th century, the cathedral was visited by numerous pilgrims, whose donations were used for urgent repairs and modernisation works. When pilgrimages were banned during the Reformation and the remaining revenues taken, it was no longer possible to maintain the building in a proper condition. It soon began to deteriorate, so rapidly that in 1575 Bishop Blethyn proposed limiting the number of people serving the church in order to save money for repairs. In addition, during the English Civil War in the 17th century, the cathedral was captured by parliamentary troops. They caused extensive damages and took the books of the cathedral library to Cardiff Castle, where it were burned. A man named Milles established a tavern in the abandoned cathedral, used part of it as a stable, and the chancel as a cowshed. In 1703, during a great storm, the church suffered additional damages, which led to the collapse of the south tower in 1723. Subsequent storms weakened the building to such a state, that it was closed due to the lack of the roofs.

In 1734, the first work began on rebuilding the church under the supervision of the architect John Wood. He renovated mainly the eastern part of the cathedral, carried out in the then popular classicist style. The late Gothic north tower was also renovated, while the nave was temporarily left in ruins. In the 19th century, the growing prosperity of the diocese allowed for a thorough restoration of the church, which was started in 1843 by John Pritchard. He removed the 18th-century transformations and completed a new south tower in 1869, built on the site of the one collapsed in 1723. The cathedral building was last seriously damaged in 1941 by the explosion of a German mine. The reconstruction of the war-damaged roof was begun by architect Charles Nicholson, and after his death in 1949, the work was taken over by George Pace, who completed repairs in 1960.

Architecture

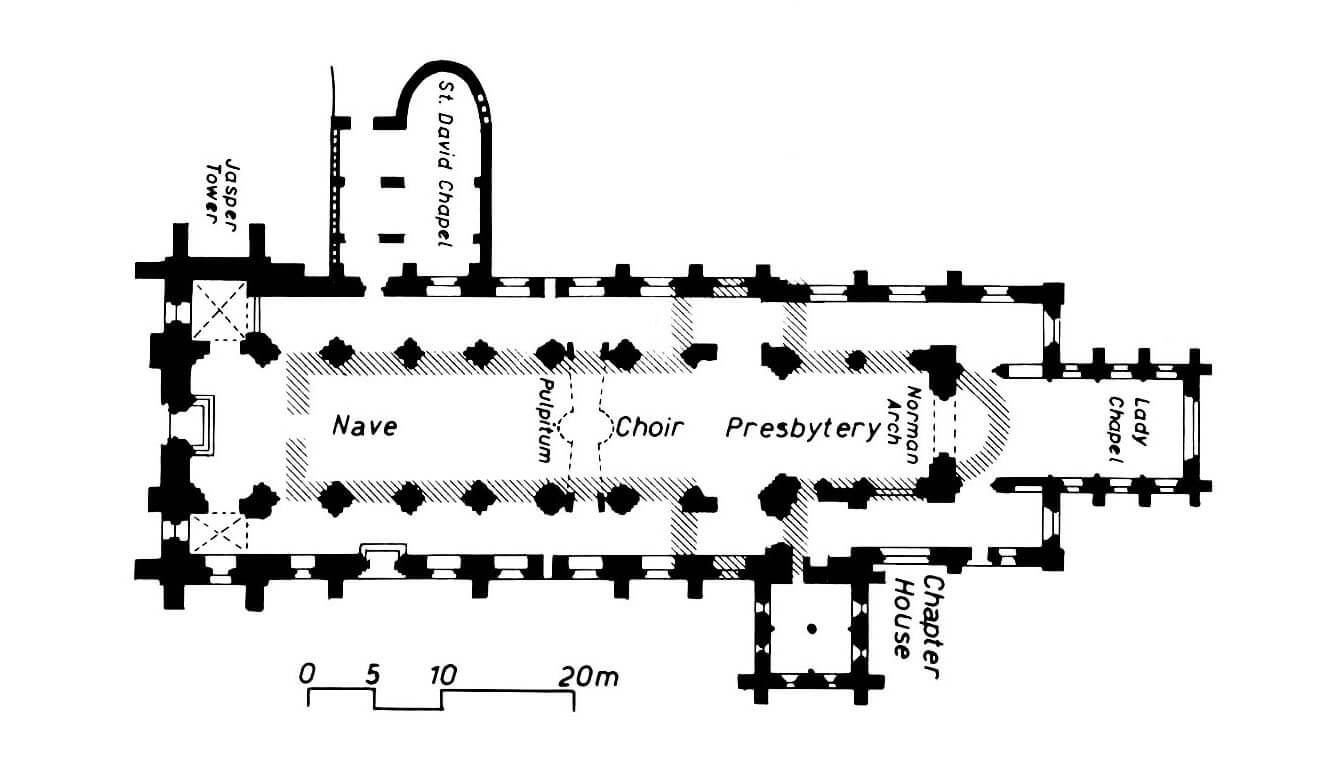

The 12th-century Romanesque cathedral was built of stone from Dundry in Somerset, England, and some local materials such as blue lias and Sutton stone. The church probably consisted of a single nave and a rectangular chancel, perhaps closed to the east by a semicircular apse. The gable façade faced west, certainly in the Romanesque style. The layout of the arcades in the eastern part of the church suggests that a short transept with a tower at the crossing was also planned, but it is not certain whether these ambitious project were ultimately realized. The chancel was separated from the apse by a Romanesque arcade with an exceptionally richly decorated semicircular and stepped archivolt (circular ornaments filled with rosettes, a motif of connected rings with sharp ridges, chevron patterns), set on an impost cornice, supported by recessed columns (one smooth and one shaped in zigzags on each side).

In the 13th century, the church had the form of a basilica with central nave, two aisles and a separate chancel. The nave was extended westwards and closed with a new façade in the form of Early English Gothic. At least one quadrangular tower was built at the side of the central nave in the south-west corner. The north-west tower was probably already planned at that time, but it is not certain whether it was completed. The Romanesque transept, if built in the first half of the 12th century, was absorbed by the side aisles in the following century. The nave then reached a length of eight bays, of which the eastern two were for the choir.

The main entrance to the 13th-century cathedral was through a semicircular portal set on an axis in the western wall, divided into two chamfered, also semicircular passages, with a niche for a statue between them. The portal was continuously chamfered along its entire length, behind which a pair of small columns were set in a deep recess on each side. Each column was divided by a ring and topped with a large capital with bas-relief leaves (on one also a seated man with cross-legged legs was made, and on another birds pecking at leaves). The portal’s archivolt was formed by two moulded shafts extending the columns. Above the entrance there were three pointed windows separated by very narrow niches with lancet arches, while above that, there was a row of pyramidally arranged blind arcades with a window in the middle, topped with trefoils and separated by small columns. At the highest, in the gable, there was a similar trefoil niche, perhaps originally housing a carved figure. The lighting of the older, eastern part of the church was most probably provided by semicircular and splayed Romanesque windows. The newer nave had windows with lancet-shaped heads.

The 13th-century cathedral was entered not only through the impressive west portal but also through smaller entrances to the north and south, with older Romanesque portals from the late 12th century being inserted into the third bays from the west in both places. These may have originally been in the west façade, but during its reconstruction, they may have been so new, that the early 13th-century builders decided to reuse them. Both portals had semicircular heads and steps filled with small columns with scalloped capitals. The archivolts were decorated with numerous zigzag herringbone patterns (chevrons), and the north portal also featured a dogtooth pattern resting on animal-shaped stops. Interestingly, the portals were constructed from two different types of stone: the north one from Sutton stone, and the south one from Dundry stone.

Inside, the church was quite modest for a cathedral, as it did not have a triforium, only clerestory windows set above pointed arcades between the aisles. The arcades themselves were richly moulded, as were the piers, which were diversified with shafts and capitals with plant motifs and corbels carved in the shape of human faces, masks and floral patterns. The four further eastern bays, built somewhat later, were set on similarly moulded, but much slimmer piers, essentially built on an octagonal plan (the arcades between the nave and aisles and the piers were built from west to east, in order to keep the Romanesque nave and transept functional for as long as possible). The more massive western piers were given a plan similar to a Greek cross, blurred by rich moulding.

In the mid-13th century, a chapter house was built next to the cathedral, located on the southern side of the church, at the third bay from the east. It was built as a small, originally entirely square building, supported by corner buttresses. Its interior featured two stories with narrow trefoil-headed windows, half the size of the first floor compared to the ground floor. Each window was topped with a drip hood repeating the shape of an archivolt, placed on consoles shaped like human heads. The lower story was covered with a rib vault, supported by a central pillar and short wall-shafts. These shafts were equipped with moulded capitals and corbels carved with leaf sprigs or human heads. The lower story housed the chapter hall proper, while the upper story may have housed a small treasury or a room intended for storing the most valuable items of the bishop’s estate.

Around 1287, the cathedral was enlarged by a rectangular chapel on the eastern side, partially embedded in the chancel extended by two bays of the side aisles. The aisles and chapel were unified by a common plinth and a cornice running beneath the window sills. The chapel was supported externally by high buttresses on moulded plinths, while the interior was covered with a cross-rib vault, enriched in each of the five bays with additional ribs along the cathedral axis and with transverse ribs. The ribs were springing from the slender shafts with bases and stiff-leaf capitals and fastened with carved bosses. Lighting for the chapel was provided from the east by a large pointed window with five-light tracery and narrower two-light windows set in the longitudinal walls. Internally, the windows were flanked by columns similar to the wall-shafts, with capitals set on the window cornice.

In the 14th century, the windows of the nave were rebuilt from the older Romanesque ones to larger, pointed, with tracery, created in the style of English Decorated Gothic. In addition, two additional small entrance portals were placed in the aisles from the north and south, facilitating communication in the spacious building. In the late Middle Ages, at the end of the 15th century, a northern tower was built at the western façade, situated next to the older, probably 13th-century southern tower. Both had elevations divided into three parts by two cornices, but the southern tower was lower. The northern one was reinforced by corner buttresses and a high stair turret, also playing a stabilizing role. The stair turret at the southern tower was already half as high. Both towers received large pointed windows with tracery and finials in the form of corner pinnacles.

Current state

The current cathedral is the result of centuries of transformations, maintained in Romanesque and Gothic style, and the effect of renovation works that had to be carried out as a result of many years of neglect and destruction from the 17th and 18th centuries. From the oldest Romanesque church, only the magnificent arcade separating the sanctuary from the Lady Chapel and fragments of walls in the southern wall of the choir with two capitals of semicircular windows have survived. Slightly later, but still from the 12th century, are two Romanesque portals: the northern and the southern one, located in the western part of the aisles. The walls of the remaining part of the cathedral come mainly from the 13th and 14th centuries, with the exception of the early modern south tower and the modern north chapel, which covered one of the Romanesque portals. The upper parts of the cathedral walls are also modern reconstruction, especially most of the clerestory of the western and central part of the church, which was destroyed in the 18th century. The results of the 19th-century work include the chapter house roof, the buttresses of the nave and many architectural details, such as gargoyles, the entrance portal to the Lady Chapel and the row of carved heads of rulers on the southern wall, currently continued on the northern wall.

bibliography:

Eryl T., Llandaff Cathedral, Crawley 1974.

Hilling J., Llandaf past and present, Cowbridge-Bridgend 1978.

Newman J., The buildings of Wales, Glamorgan, London 1995.

Salter M., Abbeys, priories and cathedrals of Wales, Malvern 2012.

Willmott M., The Cathedral Church of Llandaff, London 1907.

Wooding J., Yates N., A Guide to the churches and chapels of Wales, Cardiff 2011.