History

In 1282, English king Edward I invaded Wales for the second time, pushing opponents westward and occupying all northern territories. To strengthen his rule and control over the Welshmen, he ordered in 1283 the construction of the Harlech, one of the seven castles then built in North Wales. The work was supervised by James of Saint George, the main architect of Edward I. He managed 546 workers, 115 stonemasons, 30 blacksmiths, 22 carpenters and 227 masonry, and the project cost almost 240 pounds per month. Most of the castle was completed by the end of 1289 and cost more than 8,000 pounds, or about 10 percent of the amount that Edward spent on the construction of all castles in Wales. The first constable of the castle was John de Bonvillars, and after his death in 1287, his wife Agnes served until 1290. Harlech was garrisoned by 36 people, including 10 crossbowmen, a chaplain, blacksmith, carpenter and stonemason.

In 1294, Madog ap Llywelyn began an uprising against English rule, which quickly spread to large areas of Wales. Several English castles and towns, including Harlech, Criccieth and Aberystwyth, have been besieged. However, the shipment sent by sea from Ireland, allowed the defenders to maintain the stronghold and consequently suppress the rebellion. Following the revolt, additional fortifications were built on the outer bailey, around the track from the castle to the sea. Subsequent works on the castle were made between 1323 and 1324, after the war of rebellious barons with king Edward II. He ordered his sheriff, Gruffuld Llywd, to further strengthen the defense of the castle’s gate. The following years of the fourteenth century were peaceful for the castle, and its great importance was confirmed by the fact that for 40 years, from 1332 to 1372, its constableship was in the hands of Sir Walter Manny, one of the most trusted and ablest soldiers of King Edward II.

In 1400, another Welsh rebellion led by Owain Glyndŵr broke out. Until 1403 only a handful of castles, including Harlech, resisted the attackers (although its commander, William Hunt, was imprisoned by his own people for fear of surrendering the stronghold). The castle, however, was poorly equipped, the garrison had only three shields, eight helmets, six lances (but four of them lacked heads), ten pairs of gloves and four firearms. Harlech was besieged and in 1404, after a long siege, fell into the hands of the Welsh. It became the headquarter of Owain Glyndŵr, who used it as his base for operations until 1409. In 1408, the English forces under the command of future king Henry V besieged Harlech and his commander, Edmund Mortimer. The bombardment of the guns probably destroyed the southern and eastern parts of the outer walls, but the fall was only due to the lack of supplies and exhaustion of the defenders, who surrendered in February 1409.

In the fifteenth century, the castle was used during the War of the Roses, which broke out between the rival factions of the Lancaster and York families. In the summer of 1460, it became the shelter of Queen Margaret of Anjou, wife of Henry VI, and in the years 1461-1468 it was staffed by Lancaster supporters under the command of Dafydd ap Ieuan ap Einion. Thanks to the naturally defensive position and the chance of supply by sea, Harlech persisted, and with the fall of other fortresses, it eventually became the last main stronghold under the control of the Lancasters. In 1468 Edward IV ordered Wilhelm Herbert to mobilize an army, possibly up 7,000 to 10,000 men, to finally capture the castle. After a month’s siege, a small garrison of Harlech surrendered to the forces of the Yorks.

The castle was probably not repaired after the siege of 1468 and it became completely neglected. The survey from 1539 mentioned that the buildings were deprived of both residential and defense equipment at the time. Another inspection from 1564 noted that the interior of the towers were ruined, and the chapel and the hall were roofless. The only building kept in good condition at the castle was probably only the gatehouse. The castle’s neglect stemmed from its complete loss of military significance following the Tudor dynasty’s assumption of throne. The new rulers prided themselves on their Welsh ancestry and contributed to reducing tensions between the two nations. Furthermore, the castle never served as an administrative seat or the residence of any lord, therefore there was no need for expensive maintenance of the buildings.

When the English Civil War broke out in 1642, between royalist supporters of Charles I and supporters of the Parliament, Harlech was occupied by the royal army under the command of William Owen, who ordered the repair of the fortifications. In June 1646, a long siege began, lasting until March 1647. Eventually, the garrison of 44 soldiers surrendered to the forces of the Parliament, commanded by Thomas Mytton. The castle was the last royal continental stronghold that surrendered during the war, and the date of its capture marked the end of the first phase of the war. The castle was no longer needed, and in order to prevent it from being used by royalists, Parliament ordered its destruction. Fortunately, this command was only partially carried out, thanks to which most of the castle survived.

Architecture

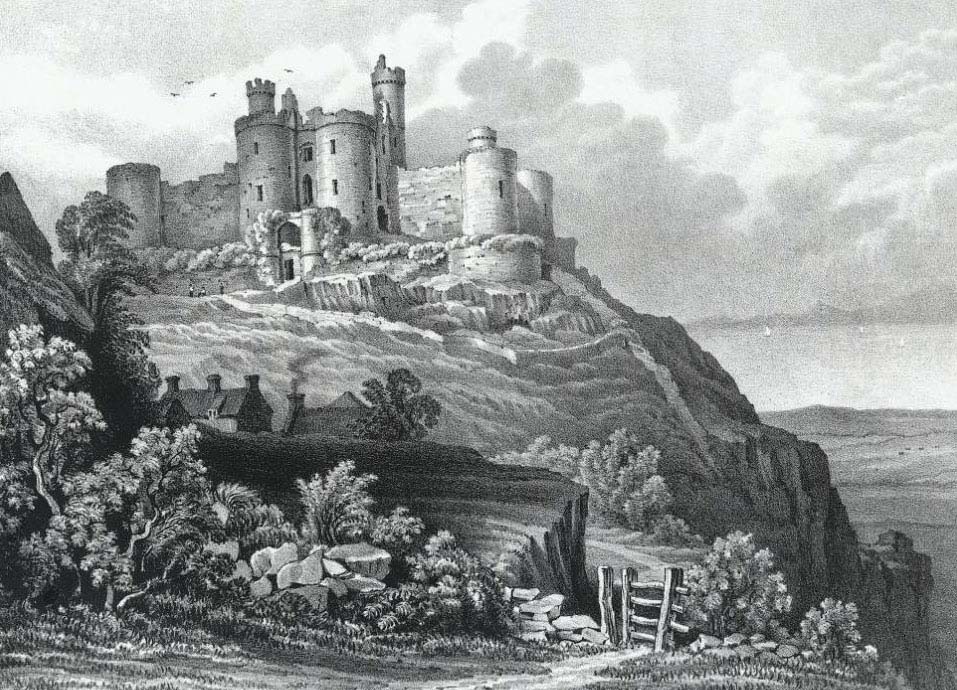

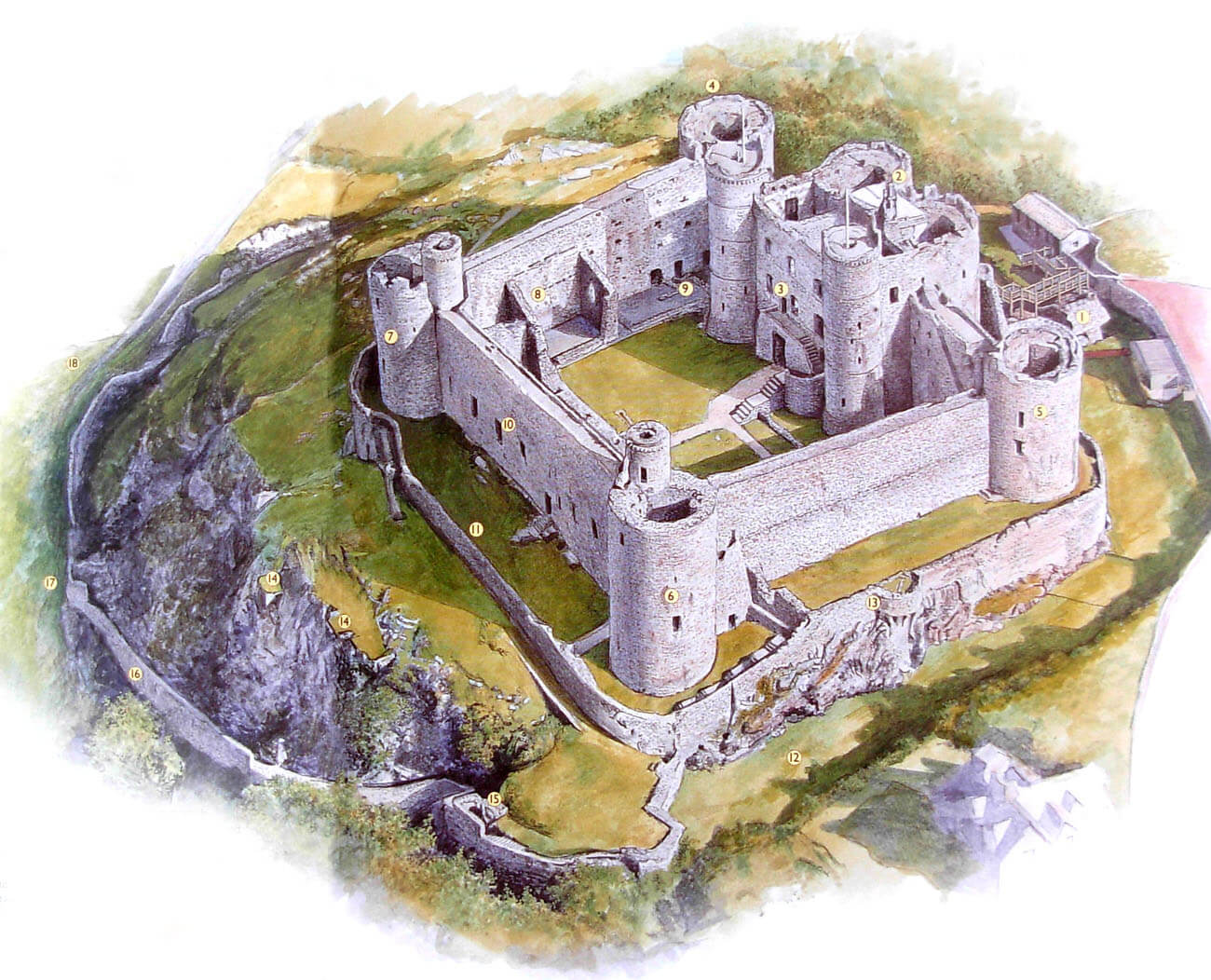

The castle was built on a 60-meter-high rocky promontory with steep and inaccessible edges on the north and west sides. The remaining two sides, which offered more accessible approach, were secured by a wide ditch cut into the rock. Despite the proximity of the sea, which originally eroded the base of the castle promontory on the west side, the ditch was never intended to be filled with water due to the significant difference in ground level. The southern part of the promontory was used for the castle core, while the more rugged northern part was left free. A leveled section of land was required for the construction of the castle, as Harlech was planned as a concentric and symmetrical structure. It consisted of two lines of defensive walls on a quadrangular plan, constructed of gray-green sandstone. Softer yellow sandstone was used for the finishing and decorative elements.

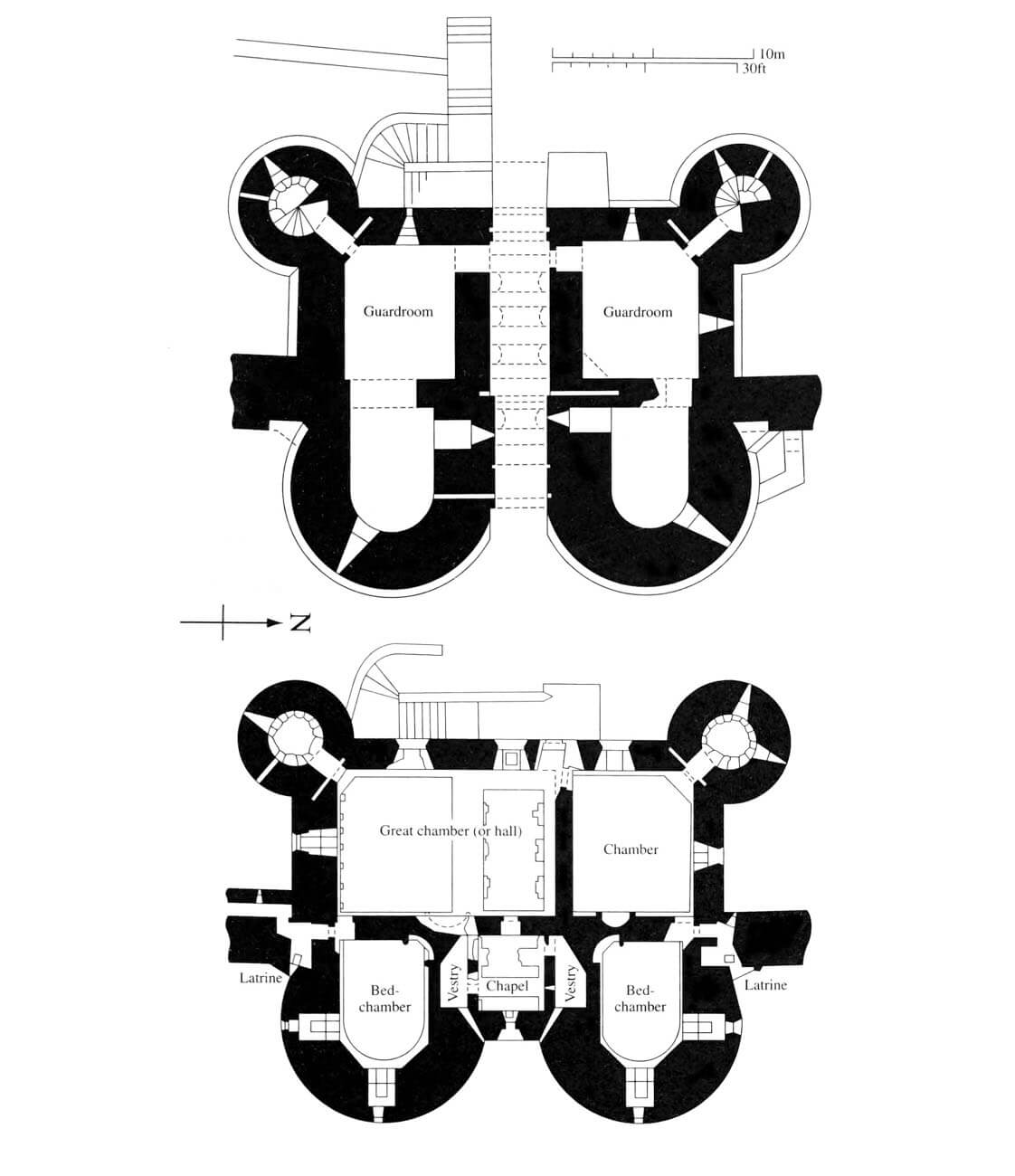

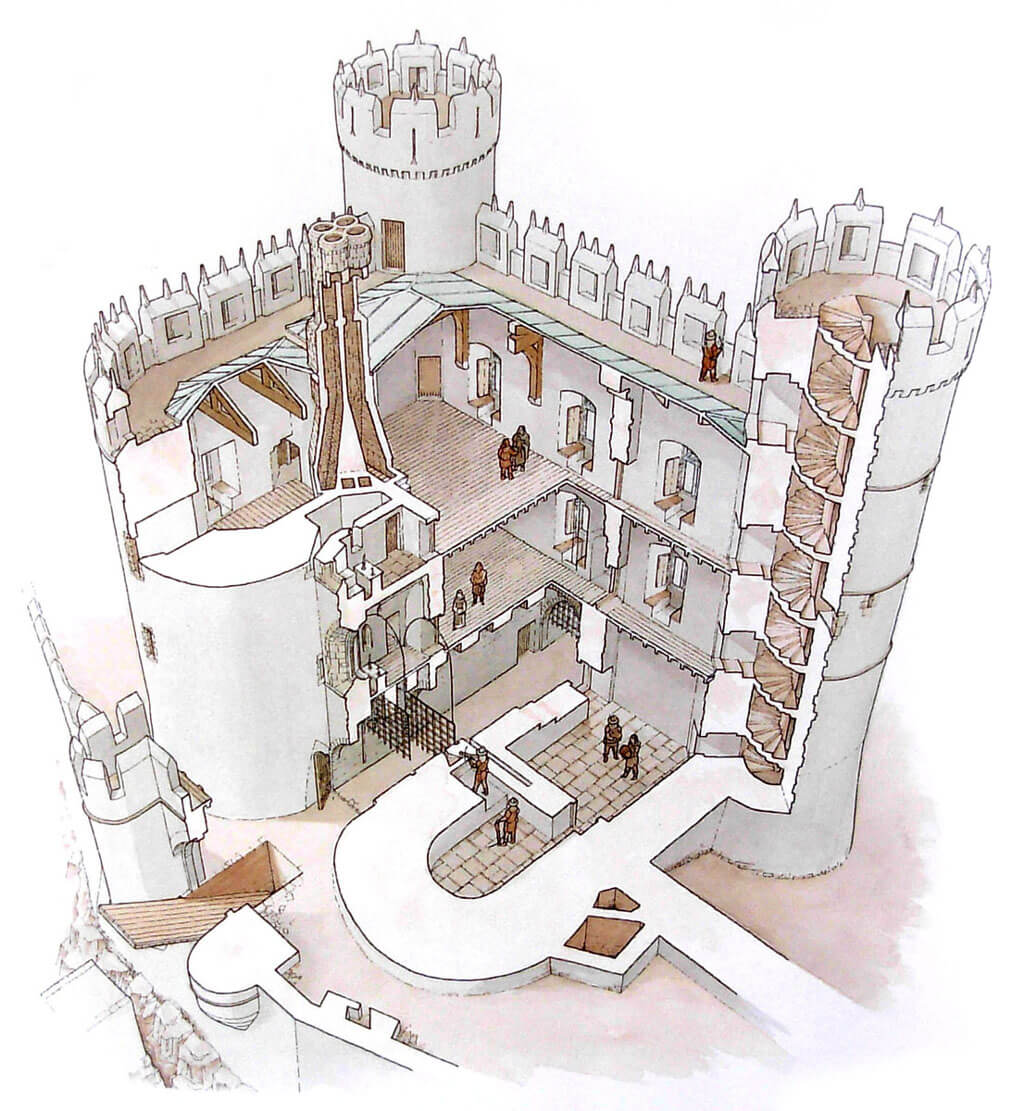

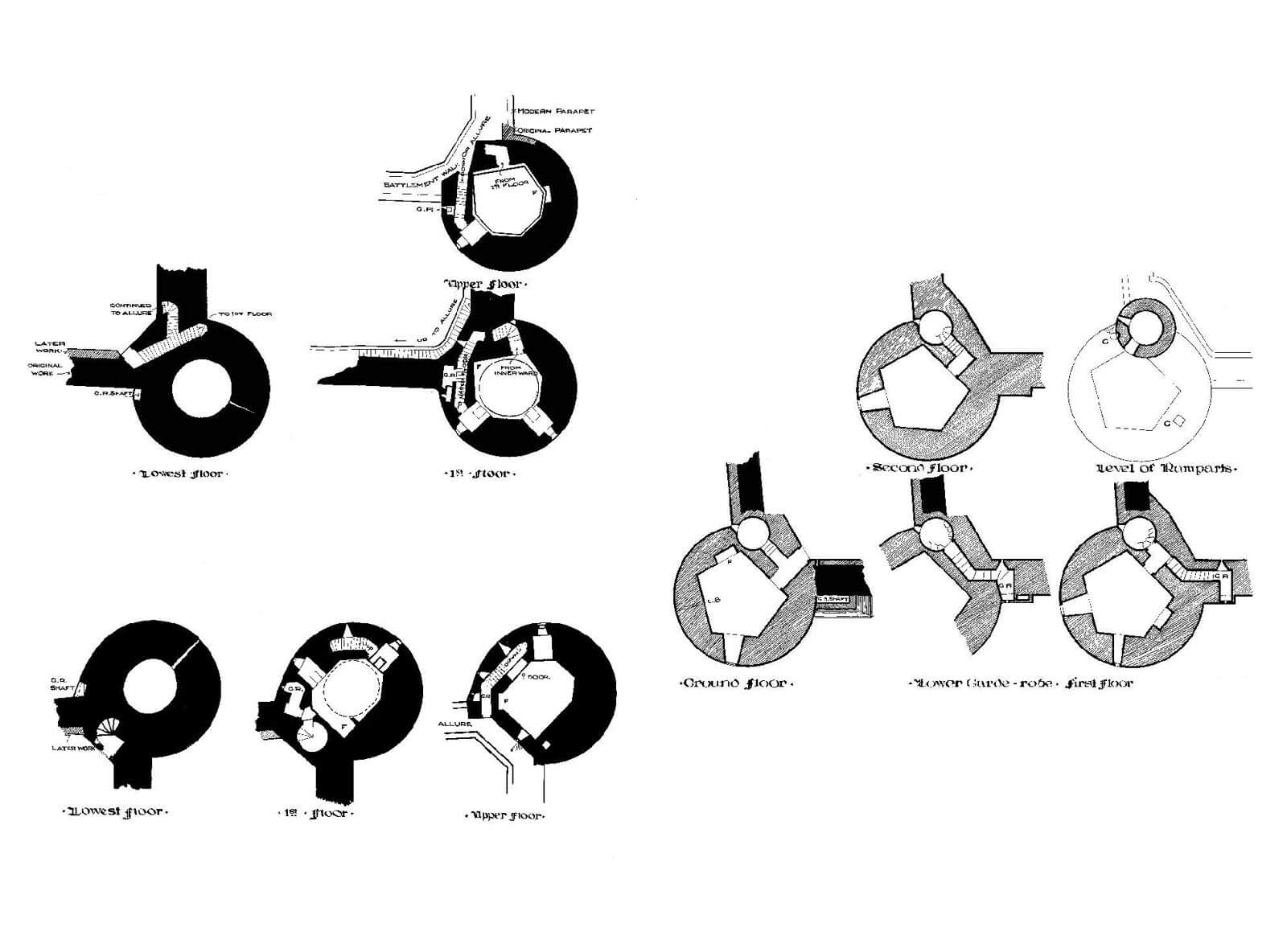

The inner defensive wall, about 3 meters thick, separated a courtyard 39 meters wide and 47 meters long in the western part and 53 meters in the eastern part. It was reinforced with four corner towers with a diameter of about 10 meters, crowned just like the gatehouse and walls with a battlement and not much higher than it. Towers had different names: in 1343, clockwise from the north-east, they were called: Le Prisontour, Turris Ultra Gardinium, Le Wedercoktour and Le Chapeltour, but in 1564 they were renamed to the tower of Debtors, Mortimer, Bronwen and Armourers. The outer defensive wall repeated the internal outline, but was much lower and thiner. In its perimeter on the southern side there was a suspended semi-circular tower (also serving as a latrine) and on the opposite, northern side, a postern outer gate protected by two horseshoe towers, open from the inside.

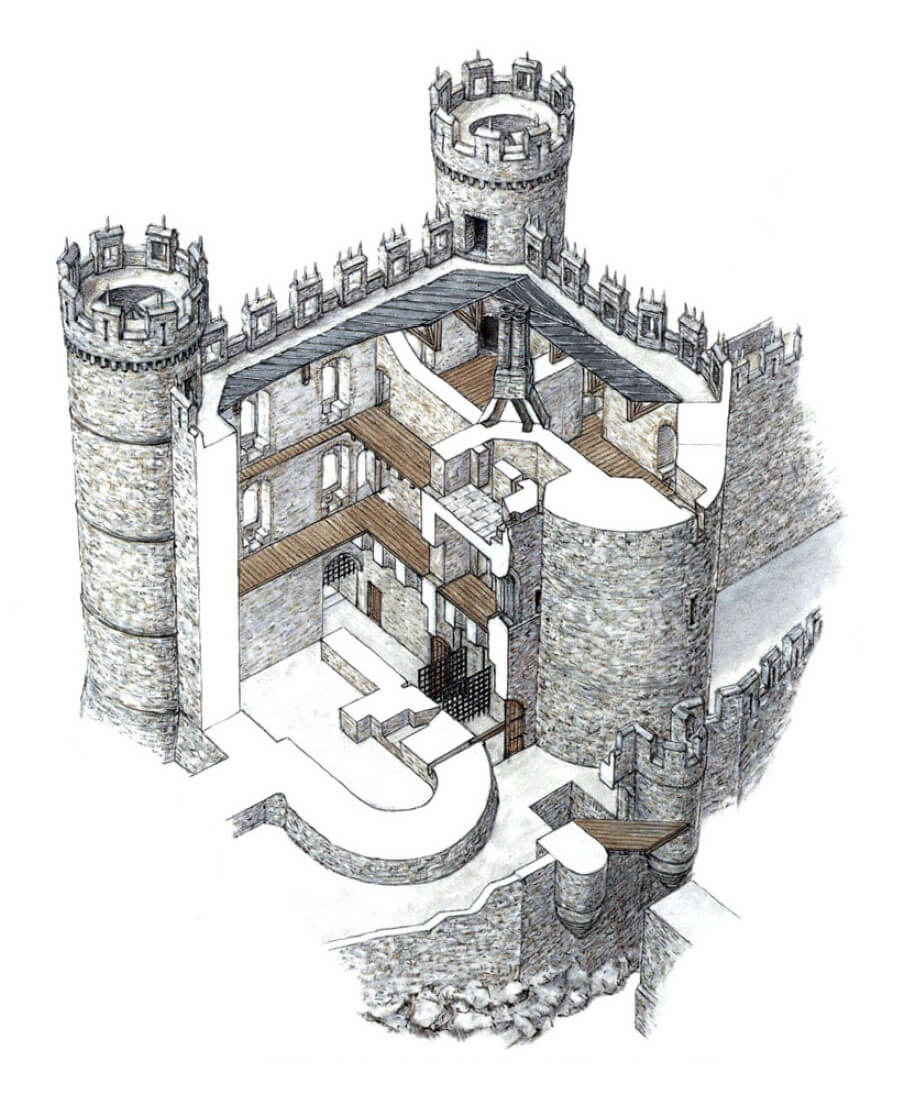

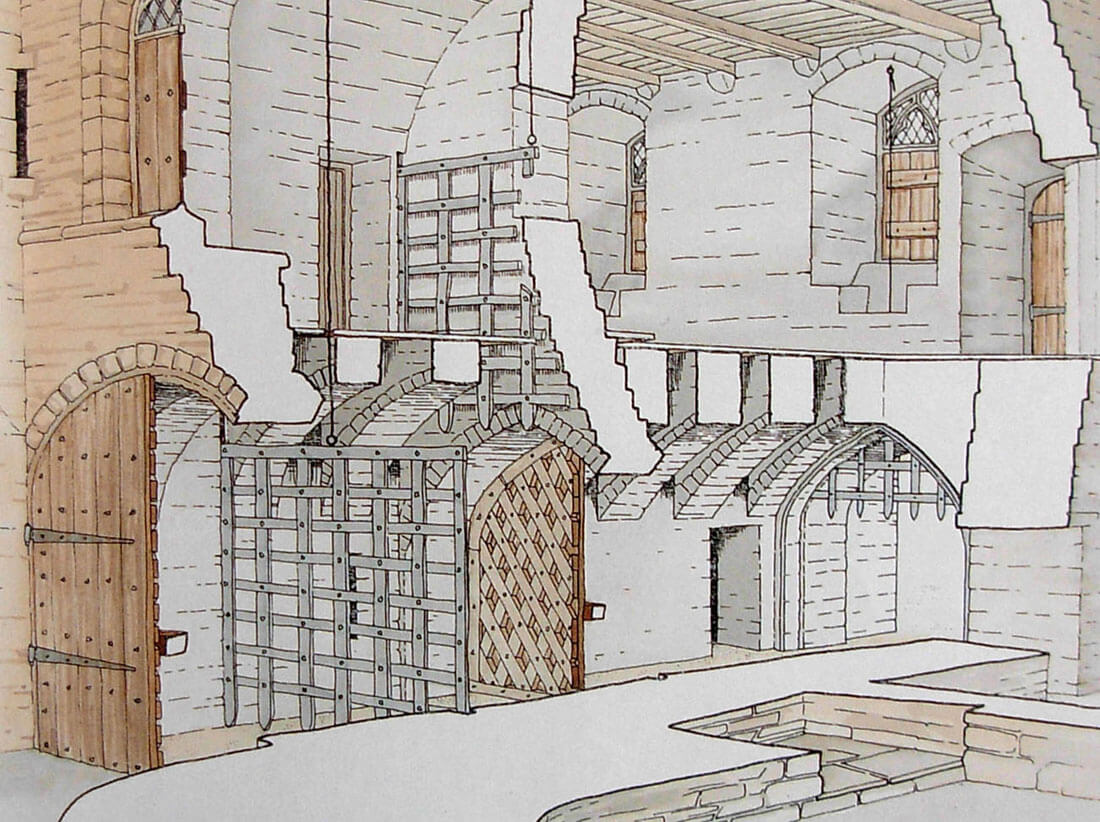

The main entrance to the castle was from the east. It required crossing a drawbridge over a ditch and two gates. The outer gate consisted of only two small half-towers flanking the passage, while the inner gate was a complex of two massive towers, shaped like an elongated horseshoe, connected at the rear by a stately gatehouse. Additionally, in 1323-1324, the castle entrance was reinforced with two quadrangular gate towers, placed one behind the other in front of the outer wall, within the ditch. One was 18 meters high, the other 12 meters high. Between them stood a stone bridge with a drawbridge at either end.

The two towers of the gatehouse protected access to the passage between them, secured by a set of three portcullises and two or three double-leafed doors, closed with internal bars, locked to openings in the wall. Additionally, the gateway was flanked by two slits from the guard chambers on either side of the passage. The rear of the gate complex was formed by two communication turrets with 1.2-meter-wide stairs, between which was a much wider external staircase on the eastern side of the courtyard. The two floors above the ground floor were occupied by spacious chambers, lit from the courtyard by six large windows. The larger and more elegant rooms were equipped with two large windows, topped by a segmental arch, set in a recess with seats on the sides. The windows were filled with trefoil tracery in their upper sections. They were glazed, unlike the lower parts of the windows, which were closed only by wooden shutters. The smaller chambers were lit by single-light windows of similar design.

On each floor of the gatehouse, the space above the passageway was divided into two rooms. Both were heated by an elegant fireplace, the smoke channels of which connected at the top in bundles, with outlets grouped in three places on the roof. The gate towers also contained small rooms, probably bedrooms, between which chapels were located on the first and second floors. The lower chapel was more elegant, with a vault above it. Both chapels were flanked by pairs of small, trapezoidal rooms, likely serving as sacristies. Furthermore, a high standard of living was provided by latrines, located within the thickness of the perimeter wall on the north and south sides of the gatehouse (the northern ones were suspended on corbels, the southern ones were set entirely in the wall). This meant that each of the two floors constituted a self-contained apartment, equipped with all the necessary amenities for comfortable living.

The northeastern and southeastern corner towers were built first. They were divided into a ground floor and two upper floors, connected by a stone staircase built into the thick wall, accessible through a portal at courtyard level. The upper heptagonal rooms had fireplaces and access through passages built into the wall to nearby latrines. The rooms in the northeastern tower were slightly larger than those in the southeastern tower, at the expense of the wall’s thickness. The circular ground floor rooms in both towers likely served as warehouses or prisons, as were lit only by a single narrow slit opening and accessible only through trapdoors in the floor of the first-floor rooms. The staircase led to the very top of the towers, where a battlemented gallery surrounded the roof of the towers. Both towers were connected to a wall-walk at the crown of the adjacent curtains, providing access to the gatehouse.

The western corner towers were built somewhat later, in 1288-1289, towards the end of the main construction phase. The southwest tower reached a height of 15.8 meters, while the northwest tower reached 15.1 meters. They were topped with additional cylindrical turrets, each 5.8 meters high, serving as watchtowers and warning posts. Both western towers contained four pentagonal rooms. Each of the two middle floors had fireplaces. The windows mostly faced the sea, with the only rooms with two windows located on the first floor. Entrances to the western towers were located in the corners at courtyard level. The southwest tower was accessed through the kitchen, while the northwest tower was accessed through a small yard between the great hall and the chapel. Vertical circulation in both towers was provided by a cylindrical staircase. An unusual feature was the lack of a connection between the western towers and the wall-walk at the top of the adjacent curtains.

The west, rectangular range of the castle was attached to the inner wall of the defensive wall. It contained a kitchen, a great hall and a warehouse and pantry between them. At the southern end of the great hall there was a wicket gate that allowed access to the zwinger (outer ward). At the northern end of the courtyard there were buildings of the chapel and bakery, which housed the castle well in the eastern part. They were all topped with mono-pitched roofs, after which holes are in the perimeter wall. Between the chapel and the kitchen there was another passage to the outer ward area and then through the gate in the outer defensive wall to the area of the outer bailey, or actually the castle rock. This small outer gate was protected by two flanking half-towers, open from the inner side. The southern part of the castle courtyard was occupied by a granary and a half-timbered building (Ystumgwern Hall).

On the west side of the castle there were wall and stairs with 127 steps, running at the foot of the cliffs to a small harbor, enabling the stronghold to be supplied by sea during the siege. They were defended by two gatehouses: the upper one equipped with a drawbridge and the lower one called Water Gate, also equipped with a drawbridge lowered over a deep pit. The Upper Gate was flanked by a towering southwest tower. At the end of the 13th century, access to the harbor and the rock on which the castle was built were further reinforced with a defensive wall on the north side. Its eastern section was connected by stairs in the crown to the outer wall in the corner of the castle core. The wall in the northern part of the castle was irregular in plan, consisting of numerous short, straight sections, with many bends adapted to the shape of the rocky edges of the hill. Two platforms were created next to the walls, used for positioning larger siege machines or cranes to assist in unloading goods.

Current state

Today, Harlech is one of the best-preserved and best-known castles in Wales. By adding it to the list of world heritage, UNESCO pointed out that Harlech is one of the “finest examples of military architecture of the end of the 13th century and the beginning of the 14th century in Europe”. Elements of the stronghold that did not survive are northern, south and west internal buildings in the ward and two external four-sided gatehouses. The outer defensive wall is lower than originally, the crowning of the the inner circumference of the fortifications, has not been preserved either. The castle’s surroundings have also changed because of the coast line being moved several hundred meters away. Currently, the castle is under the care of the Cadw government agency, which makes the monument available to tourists. Unfortunately, in recent years, the entrance to the castle has been disfigured by a modern metal bridge that replaced the earlier timber one.

bibliography:

Gravett C., The Castles of Edward I in Wales 1277-1307, Oxford 2007.

Guy N., The Harlech castle garden and privileged spaces of elite accommodation, „The Castle Studies Group”, No. 31/2017-2018.

Haslam R., Orbach J., Voelcker A., The buildings of Wales, Gwynedd, London 2009.

Kenyon J., The medieval castles of Wales, Cardiff 2010.

Lindsay E., The castles of Wales, London 1998.

Salter M., The castles of North Wales, Malvern 1997.

Taylor A. J., Harlech Castle, Cardiff 2002.

Taylor A. J., The Welsh castles of Edward I, London 1986.