History

The first, then still timber castle in Grosmont was probably built in the second half of the 11th century by the Norman conqueror William Fitz Osbern, Earl of Hereford. Shortly after William the Conqueror’s invasion of the island and the victorious battle of Hastings in 1066, he received border areas with Wales, where he erected castles in Chepstow and Monmouth, from which he undertook expeditions to further lands of central and eastern Monmouthshire. Grosmont was one of three wood-earth strongholds (the others were Skenfrith and White Castle) built at that time in the Monnow Valley to protect the route from Wales to Hereford and to control the conquered lands. It was built in an area whose population was entirely Welsh, which is why the rebellions and uprisings against Norman superiors caused it to be of great strategic importance for a long time.

William Fitz Osbern did not enjoy his Welsh lordship for too long, as he was killed in the Battle of Cassel in Flanders in 1071. William’s son, Roger de Breteuil, lost his castle because of his involvement in the rebellion against William the Conqueror in 1075. After a short period of possession by the Crown, Grosmont at the beginning of the 12th century became the property of the Anglo-Norman nobleman Pain fitz John, royal official of Henry I. When the English king died in 1135, there was a major Welsh revolt, which made king Stefan reorganize the landholdings along this section of the Marches, transferring the Grosmont castle and the nearby Skenfrith and White Castle fortifications back under the control of the Crown, to create an authority known as “Three Castles”.

Under King Henry II Plantagenet, there was a brief period of détente between the Welsh and the Anglo-Normans in the 1160s. However, conflict with the natives quickly returned when the de Braose and Mortimer families resumed their expansion in the 1170s. In retaliation, in 1182 the Welsh under Hywel ap Iorwerth attacked the nearby castle at Abergavenny, forcing the king to reinforce Grosmont through the royal official Ralph of Grosmont. The modest sums spent on building work at the time suggest, that the castle was still small and wooden at that time.

In 1201, King John gave the “Three Castles” to Hubert de Burgh, a growing royal official, experienced in the fighting in France and familiar with the latest trends in military architecture. The new owner and then his son Hubert de Burgh II, by 1232 transformed the castle into a modern for the 13th century standards, stone building, which defense was based on flanking towers extended beyond the perimeter, but which also served as a residence. In 1227 the ruler Henry III gave Hubert 50 oaks from the royal forest for construction works, but in 1232, Hubert fell out of royal favors and was deprived of his possessions. The castle’s management was granted to king’s servant, Walerund Teutonicus. A year later, king Henry led the army to Wales against the rebellious Richard Marshall, Earl of Pembroke and his Welsh allies. He set up a camp at Grosmont, on which Richard carried out a night attack. He did not get the castle itself, but he forced the royal army to flee.

In 1234, Hubert reconciled with the king. The castles were returned to him, but in 1239 he again fell into conflict with Henry III. Grosmont was taken away from him and put under the command of Walerund. He did some of Hubert’s work, including the construction of a new chapel. In 1254 Grosmont and his sister strongholds were granted to the eldest son of king Henry, and later to king Edward. In 1262 the castle was prepared for a siege in response to the attack of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd on Abergavenny. Gilbert Talbot was ordered to be garrisoned “by every man, and at whatever cost”, but Grosmont missed the threat. In 1267, Edmund, Earl of Lancaster and capitaneus of the royal forces in Wales received the Three Castles.

The conquest of Wales by Edward I in 1282 reduced Grosmont’s military importance. The 14th century saw little further modernisation of its fortifications, although in the first half of the 14th century, under Henry Lancaster or his son Henry of Grosmont, the interior of the castle was extended with high-quality living quarters. As with most Welsh castles, the last military episode in Grosmont’s history was the revolt of Owain Glyndŵr in the early 15th century. In 1404, a battle took place between the Welshmen and the victorious Richard Beauchamp, the Earl of Warwick, under the walls of the Grosmont, leading to an English victory. The following year, the castle was besieged by Owain’s son, Gruffudd, but it was relieved by the by prince Henry.

In the third decade of the 16th century, Grosmont Castle ceased to serve residential purposes. Deprived of its importance and care, it quickly fell into ruin. By 1563, the bridge to the castle had already collapsed and although the external walls were intact, the interior was in a state of decay. The wooden parts had rotted and the iron and lead had been stolen. The ruins were the property of the Earls of Lancaster until 1825, when they were purchased by Henry Somerset, Duke of Beaufort. In 1902, Grosmont became the property of the antiquarian and historian Sir Joseph Bradney. Twenty-one years later, the ruined castle was taken over by government institutions, under whose supervision the first renovation works began.

Architecture

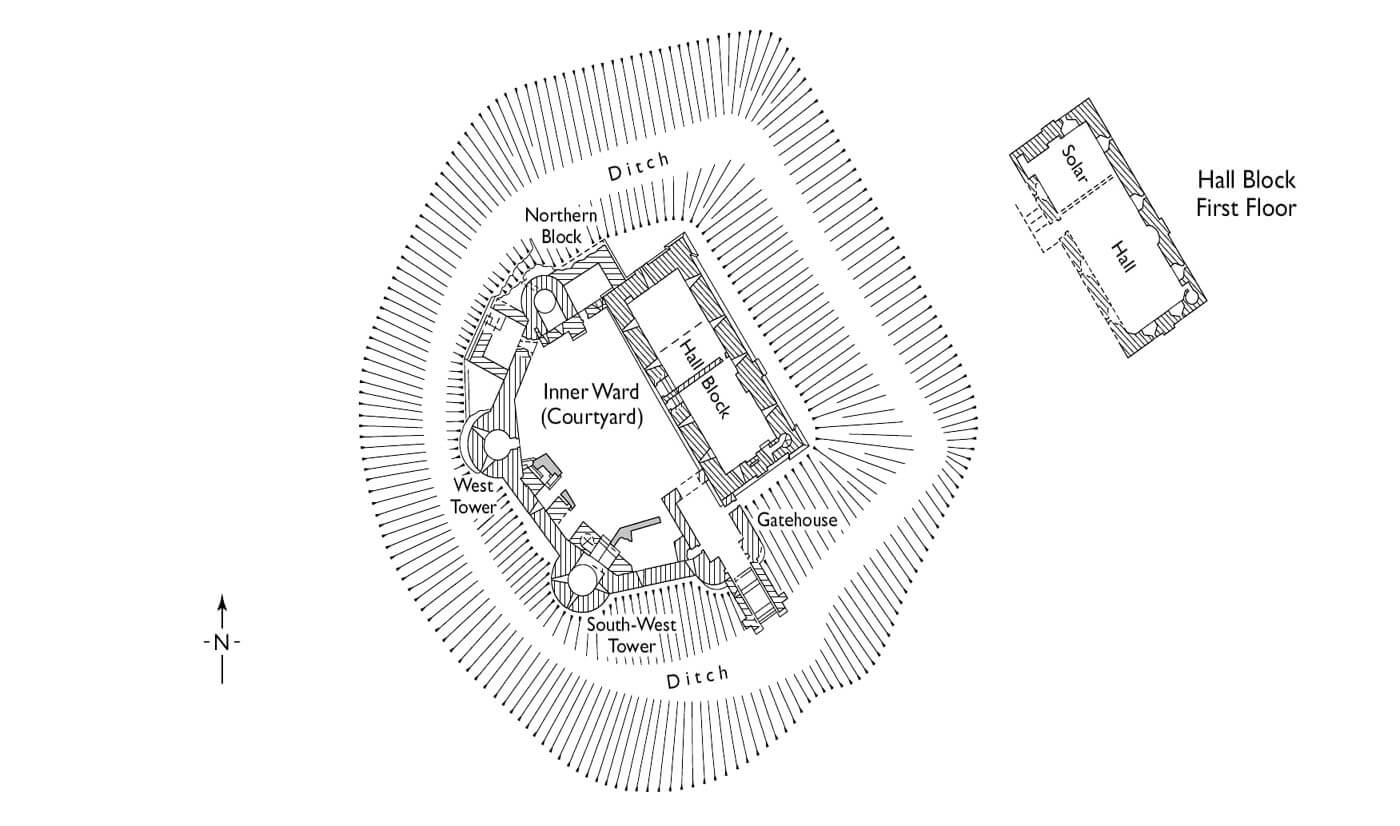

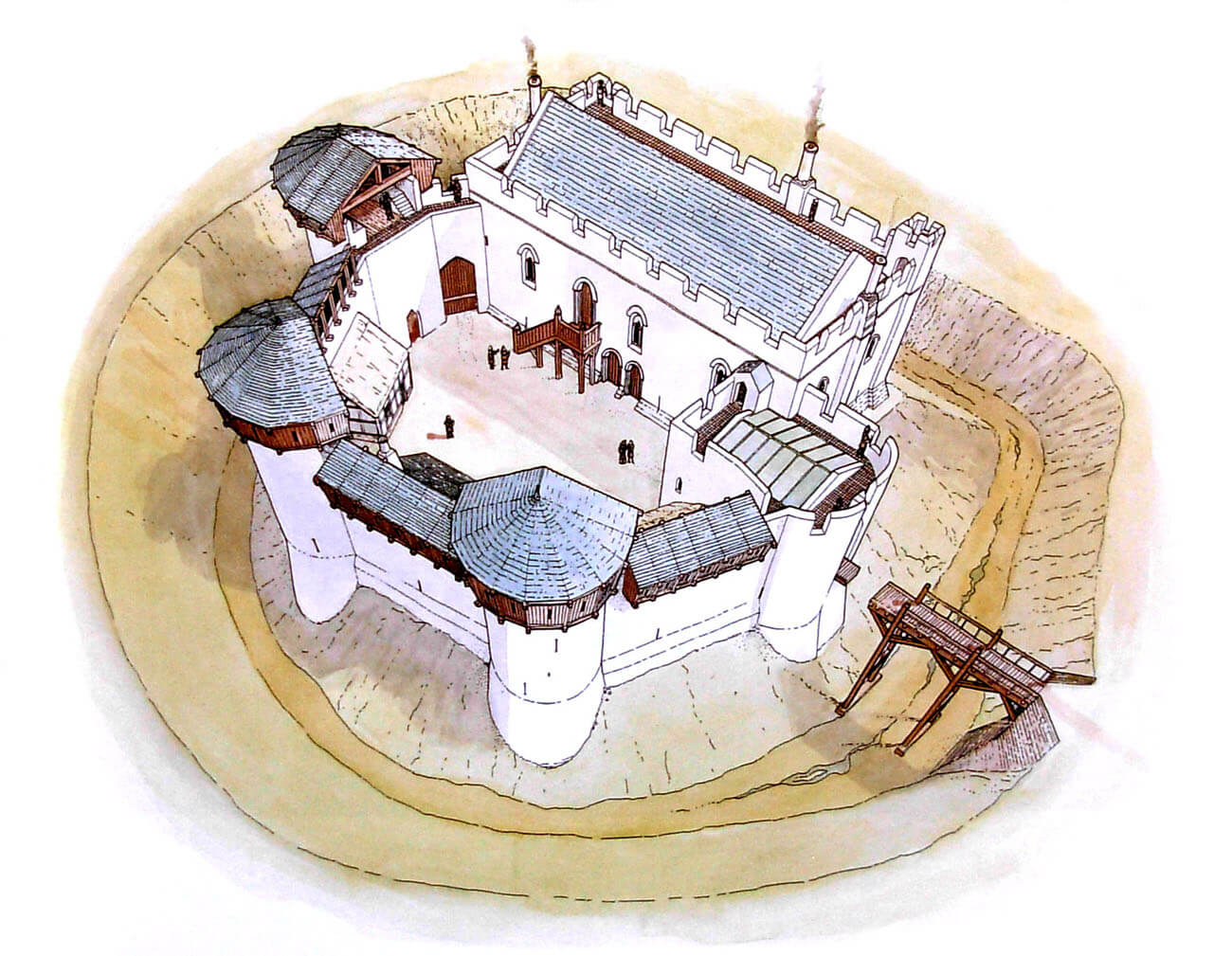

The original castle from the 11th century was built of wood in the form of a motte and bailey. It was probably either a wooden keep placed on an earthen mound, or a closed defensive perimeter (ringwork) protected by a palisade and a ditch. It was situated on a large elevation of land, the slopes of which fell to the east towards the bend of the Monnow River flowing through the valley. The river at the foot of the hill made a bend, but the castle was located on the outside, not the inside, of the meander. At a slightly greater distance, from the south, the castle was surrounded by the Tresenny Brook, which flowed into Monnow to the south-east. To the west and south-west of the castle, from where the most convenient access road led, a small outer bailey and settlement with an impressive church of St. Nicholas developed.

The oldest stone element of the upper ward was a rectangular residential range measuring 29 by 9.8 meters, from the beginning of the 13th century, which was located in the eastern part of the courtyard. Its massive walls were 2.2 meters thick, were reinforced with a battered plinth securing the building from the side of the slopes of the ditch, and also supported by pilaster strips, situated not only in the corners, but also in places where fireplaces were located inside. The ground floor housed a pantry and a kitchen, which were accessed through two western portals with doors closed from the inside with bars placed in holes in the wall. The lighting of the lower floor was provided by eleven narrow slit windows. In the kitchen, which occupied the southern part of the ground floor, there was a fireplace with a chimney towering over the central part of the southern wall. The first floor was accessed by external wooden stairs, but the servants could also use spiral stairs set in the thickness of the wall in the south-eastern corner. On the first floor of the building in the northern part there was a private chamber (solar), while in the south most of the floor was occupied by a great hall. Both the hall and the private chamber had fireplaces. Both rooms were well lit by larger windows than those at the bottom, additionally equipped with seats from the side of the internal niches. The great hall was where meals were eaten, feasts were organized, and guests were received, while the northern chamber was a private room and probably a bedroom.

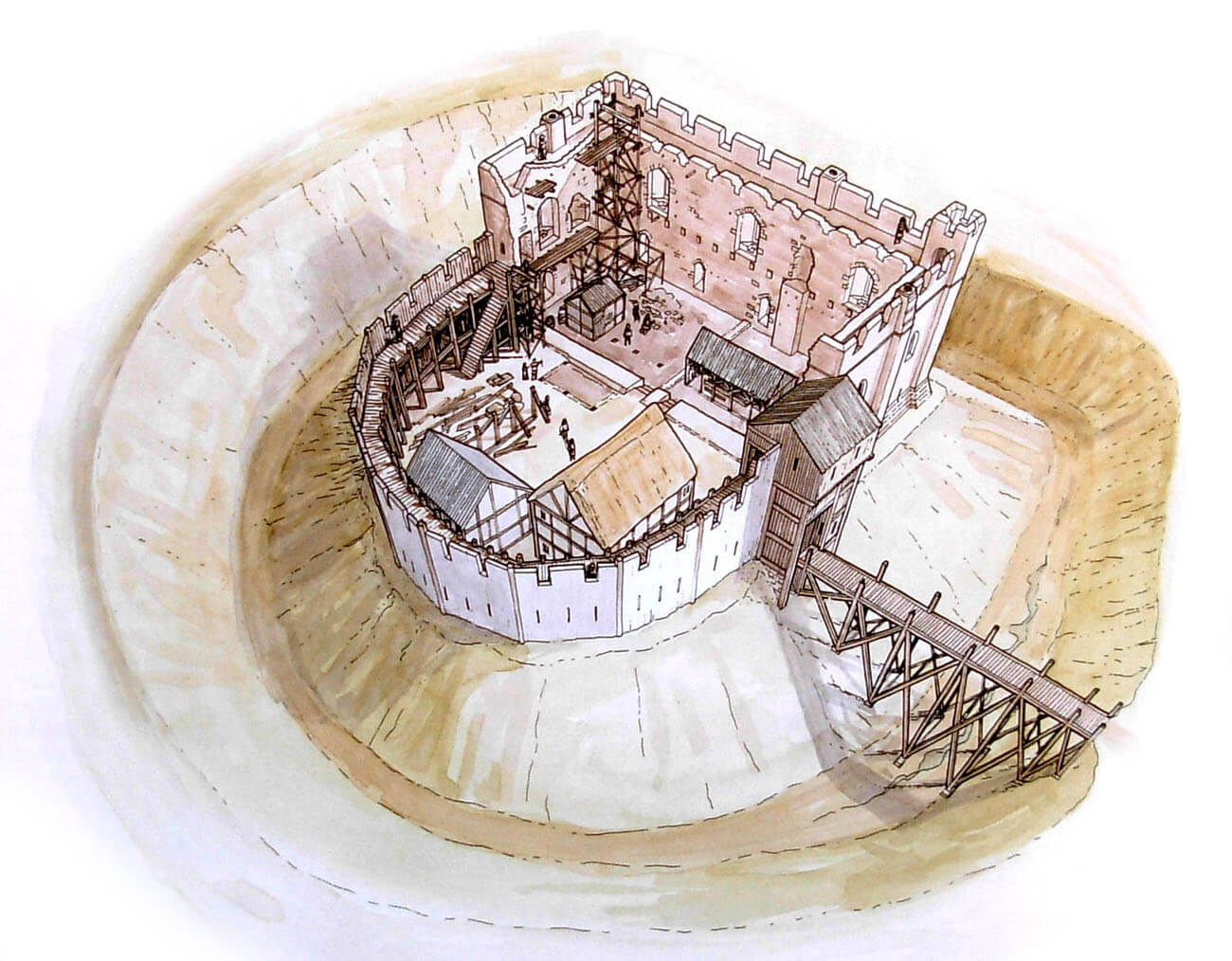

In the 1220s, a polygonal defensive wall was erected, added to the older building from the west and reinforced with three towers. At the base, i.e. where walls were the thickest, both the curtains and the towers received sloping external elevations – batter, ensuring better stability at the moat slope. From the south and west, the curtains in the ground floor were pierced with single arrowslits, with splayed embrasures directed towards the courtyard. In the crown the curtains were topped with a wall-walk with a crenellated parapet, widened by a wooden hoarding porch. The wall-walk had to be connected to the towers in order to ensure uninterrupted communication along the defensive perimeter.

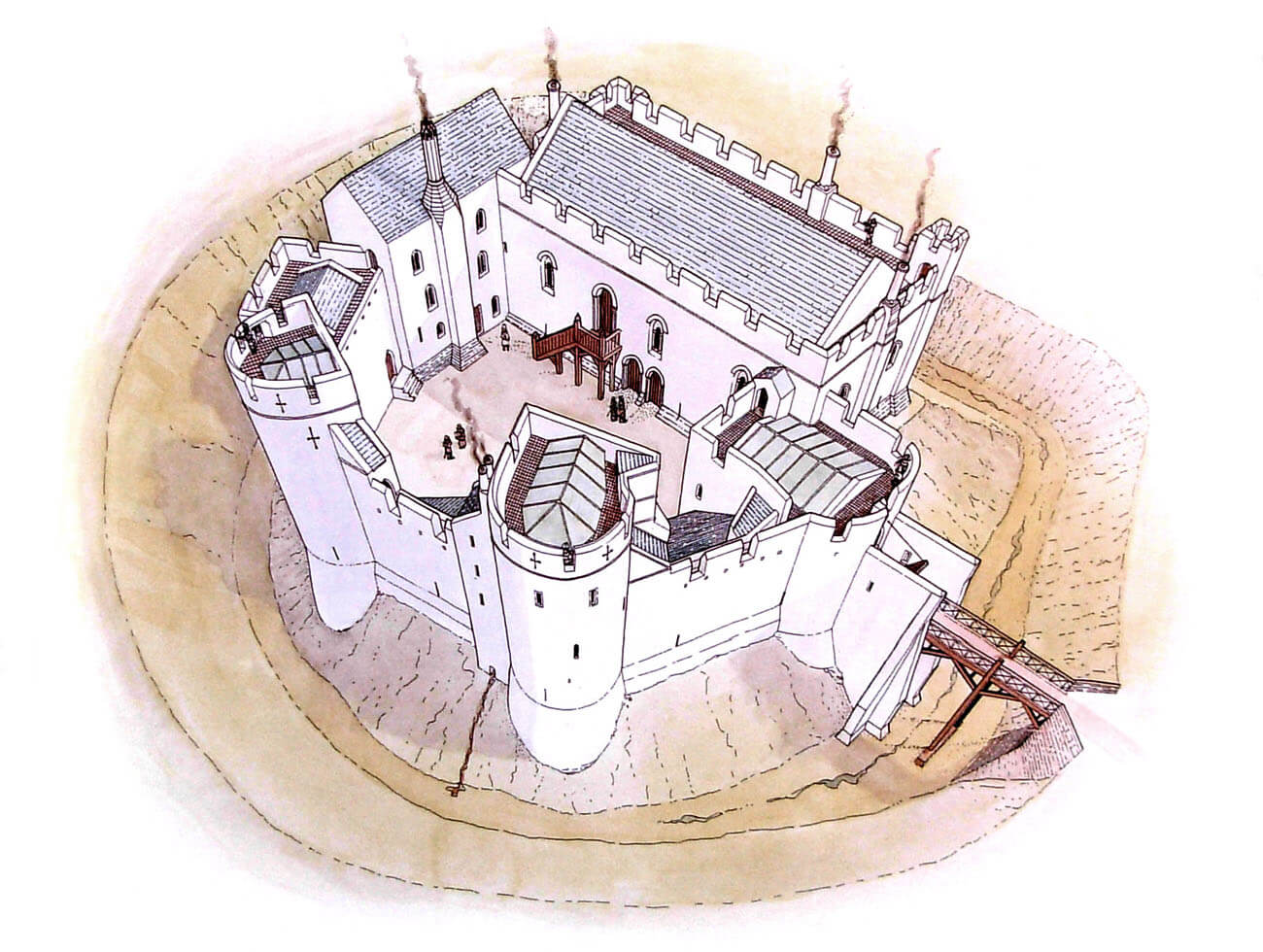

Entrance to the courtyard since the 1220s was provided by a stone southern gate, placed in a two-storey building measuring 13.3 x 8.2 metres, created on a plan similar to a quadrangle, but with rounded corners. The gatehouse was slightly protruding in front of the neighbouring curtain towards the moat, with most of the mass within the courtyard. It was a relatively modest structure, much simpler than gates with two towers flanking the central entrance, which were very popular only a little later. Inside, there was a gate passage at the bottom, and above the wooden ceiling a room for the guards. There were also two portals pierced in both sides of the building at the bottom. The north-eastern one led to a narrow, flat platform between the wall and the moat, and the other to the first floor. In the 14th century, the gatehouse received an additional foregate, protecting a wooden drawbridge spanning a moat and a pit created between the foregate walls.

Two towers on the west side and one on the north side had a horseshoe shape with an outer diameter of approximately 8 meters and protruded beyond the perimeter of the walls enabling side fire. All, apart from three above-ground floors, were also equipped with round basements, accessible through openings in the ground floor and able to contain significant amounts of supply. This infrequent solution may have been a reflection of Hubert de Burgh’s experience of defending Chinon and Dover castles that have been subjected to prolonged sieges. In the fourteenth century, the western towers were raised and crowned with battlements instead of earlier hoarding. Their two upper floors were equipped than with chambers heated with fireplaces. A portal, accessible after a few stairs from the level of the courtyard, led to the south-west tower, enlarged from the side of the courtyard by a 2.5-meter wide part, in which a spiral staircase to the upper floors was immediately on the right of the entry. These upper floors were also accessible via wooden stairs attached to the inner face of the perimeter wall between the western towers. Their construction was based on two stone pillars.

In the fourteenth century, the northern tower along with the postern next to it were transformed, and ground floor of the tower was incorporated into the northern range, formed with a characteristic octagonal, gothic chimney from the courtyard side. This building had three floors with comfortable chambers heated by fireplaces. Next to it, on the west side, a new, rectangular tower was erected entirely in front of the face of the walls, probably to reward the loss of an older horseshoe tower. Inside, among others, there was a latrine and an unlit basement. The remaining buildings of the castle were timber, smaller houses erected at the courtyard at the inner faces of the defensive walls. In the fourteenth century or at the end of the Middle Ages, some of them were demolished, and some were replaced by stone ones. At the time, the building on the west side of the gatehouse probably housed service and garrison quarters. At the outer ward there was a rectangular granary or stable.

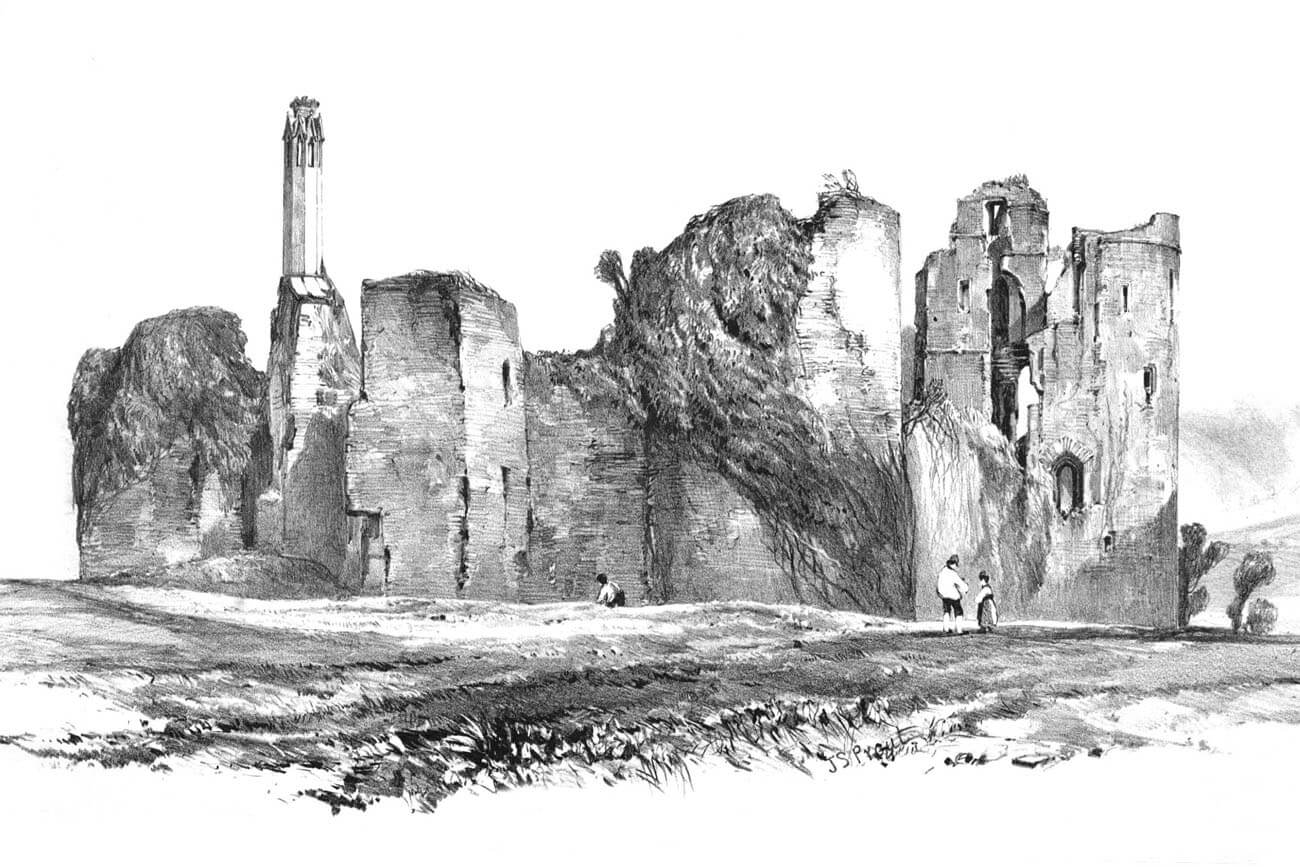

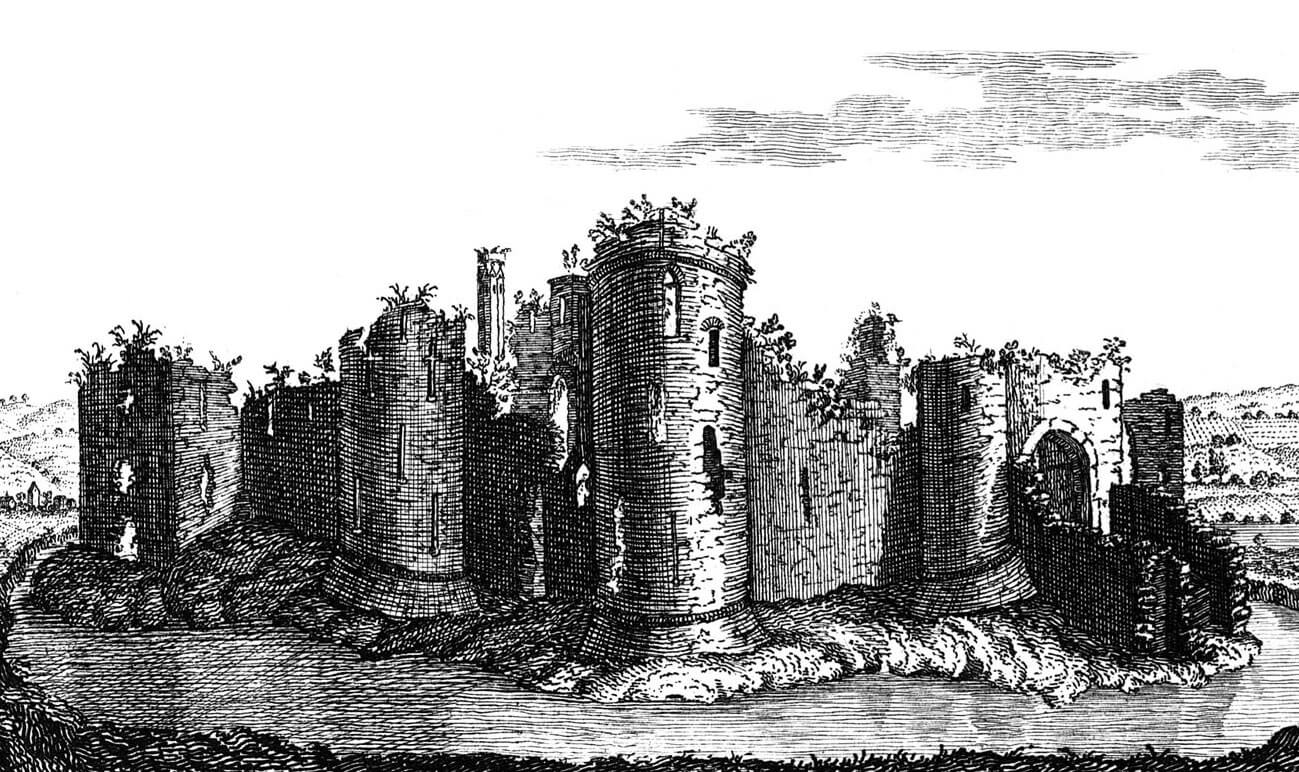

Current state

The castle has survived to modern times in the form of a ruin. Most of the defensive walls have survived, two western towers and the outer walls of the main building on the eastern side. In a much worse condition there is an gatehouse and a four-sided tower. From the north wing only the chimney and a fragment of the wall facing the courtyard remain. Characteristic that almost all buildings in the castle area have been deprived of stolen ashlar, which is why they are missing corners, as well as window and entrance jambs, which left large gaps. The moat around the castle is visible. The monument is under government protection and open to the public.

bibliography:

Kenyon J., The medieval castles of Wales, Cardiff 2010.

Knight J., The Three Castles: Grosmont Castle, Skenfrith Castle, White Castle, Cardiff 2009.

Lindsay E., The castles of Wales, London 1998.

Newman J., The buildings of Wales, Gwent/Monmouthshire, London 2000.

Salter M., The castles of Gwent, Glamorgan & Gower, Malvern 2002.