History

The origins of All Saints’ Church in Gresford date back to the 13th century (it was recorded in the Domesday Book of 1254 and 1333), but its original form was completely altered in the first half of the 14th century and then during a major late medieval rebuilding in the late 15th century and early 16th century. Presumably, such a large and elaborate church was built in a small village due to pilgrimages to an unknown relic. Another explanation could be the support of Thomas Stanley, Earl of Derby, stepfather of King Henry VII, who is known to have funded a large window in the church’s east wall in 1500.

Thomas Stanley’s brother, Sir William Stanley, intervened at the Battle of Bosworth, securing Henry Tudor’s victory and helping him ascend the throne as Henry VII. Later, however, William Stanley supported the cause of Perkin Warbeck, who claimed to be one of the legitimate sons of King Edward IV, and was subsequently executed. According to legend, the 15th-century reconstruction of Gresford Church was financed by Henry VII to show his sorrow for the execution of a man who had once served him. However, Stanley’s execution took place in 1495, by which time the church’s reconstruction was already nearing completion.

The first early modern modifications to the church’s architecture and furnishings were a result of the changes brought about by the Reformation and the decline of pilgrimages. Around 1634-1635, the Gothic reredos was removed, and a new altar was placed against the east wall of the church, blocking the processional path. Fortunately, the Victorian renovation of the church from 1865-1867 respected the historic architecture of the building and did not introduce drastic changes. In 1907, during further renovation work, a carved altar from the Roman period was discovered in the church crypt, dating from around 100-350 A.D.. In the years 1913-1914, further repairs work took place, and in 1921 the northern porch was built.

Architecture

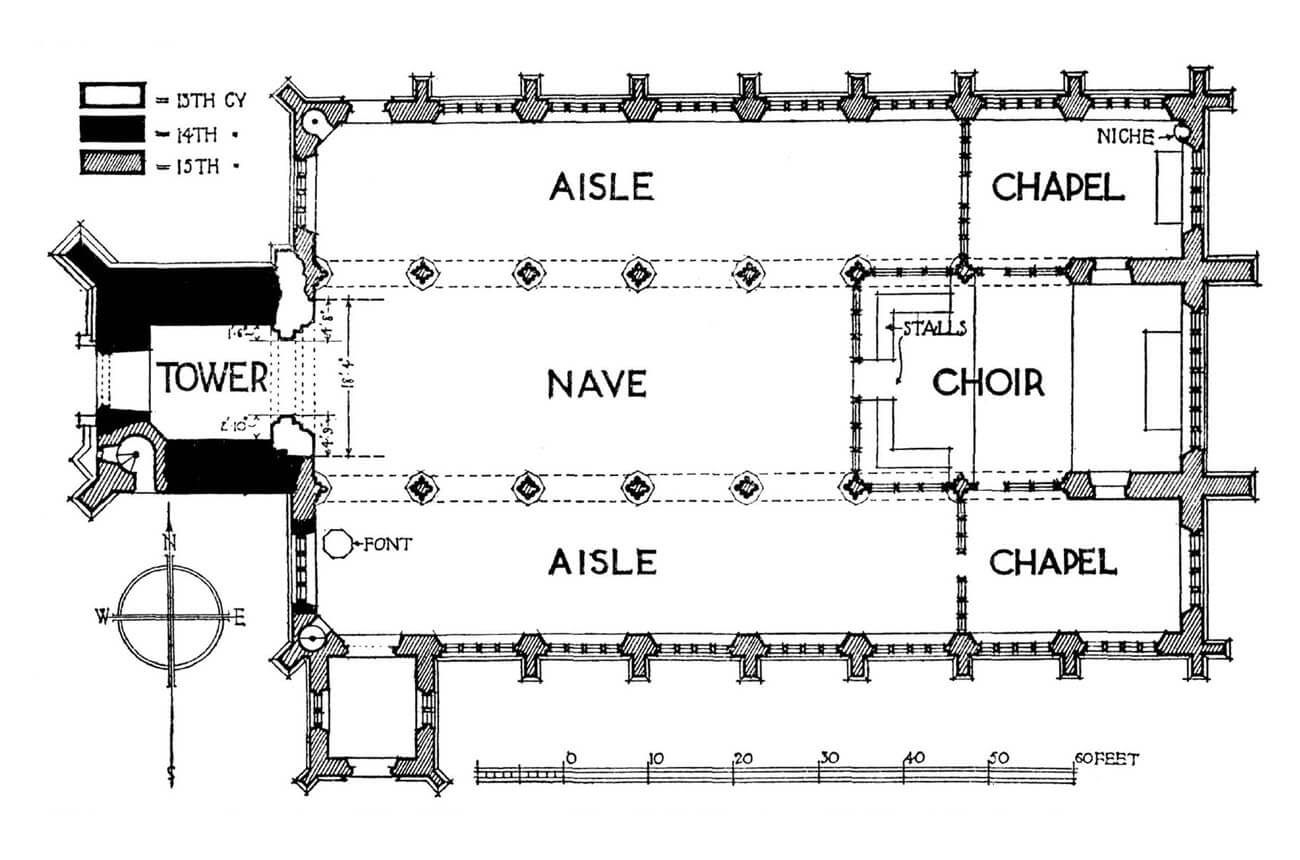

The church originally consisted of a 5.6-meter-wide nave (narrower than the late medieval central nave) and a quadrangular chancel, which was not externally separated. In the 14th century, the church was extended eastward, and a vaulted crypt was placed beneath the chancel, thanks to the slope of the terrain. The crypt had the same width as the chancel and had small, barred openings to the north and south. The 14th-century chancel likely terminated at the crypt line with a straight wall. Also in the 14th century, the church was preceded on the west by a simple and initially low tower, opened towards the nave with an arcade featuring three chamfered orders separated by grooves.

In the 15th century, the church was rebuilt in the English Perpendicular Gothic style. Only the tower and part of the nave walls on the west side were preserved. The north and south aisles were added, the central nave was widened, and the chancel was once again extended eastward by 4.3 meters. This extension allowed for the creation of another crypt beneath the floor, although this time without a vault. Ultimately, an aisled basilica was created, again without an externally separated chancel, which was surrounded to the south and north by two-bay chapels with walls in line with the walls of the side aisles. Additionally, the entrance in the first western bay of the south aisle was preceded by a 16th-century porch.

The walls of the aisles, chapels, and central nave were adorned with a parapet with decorative battlements. Seven windows each on both longitudinal elevations were set between small, two-stepped buttresses. The central nave was pierced to the north and south by eight windows, all with significantly lowered pointed archivolts, very popular in late medieval Wales and England. Further windows illuminated the aisles from the east and west, while an older pointed window from the 14th century was reset to the south aisle. Traditionally, the most impressive window, with its seven-light tracery, was placed on the eastern wall of the central nave. The remaining windows were filled with four-light tracery (except for the three-light eastern windows of the clerestory), featuring motifs of cinquefoils and trefoils inscribed in ogee and pointed arches. Furthermore, the windows were decorated with hoodmoulds supported by carved heads or whole animals. The gutter chutes were decorated with gargoyles in the form of monkeys or grotesque creatures. Gargoyles, beasts, and animals also adorned the buttresses and the band along the entire length of the aisles. Some of the stained glass in the windows was transferred from the dissolved Basingwerk Abbey.

The eastern wall and tower of the church were adorned in the 16th century with Gothic pinnacles, which on the tower sprang from high, stepped corner buttresses and parapet. The buttresses also featured canopy-like recesses for sculpted figures, supported by mask-shaped corbels. While the older section of the tower was lit by medium-sized, two-light windows with pointed heads, the late Gothic section was pierced on each side by very large windows topped with ogee arches, richly decorated with crockets and fleurons. Furthermore, the tower was decorated halfway up with an elaborate frieze, which distinguished the 14th-century section from the part of the tower added in the 15th/16th centuries. A spiral staircase embedded in the thickness of the tower’s southwest corner was likely another late medieval addition.

Inside, the nave of the church was divided by moulded, pointed arcades descending onto pillars framed by half-shafts. The arcades were set on moulded imposts, supported by several small capitals at the ends of the half-shafts. The pillars were placed along the line of the external buttresses, creating a division into six bays in each aisle and five in the central nave. The two-bay chapels opened onto the chancel with arcades on the western side and portals set in the walls on the eastern side. These formed part of the processional ambulatory around the main altar, which was left in its original location during the late Gothic reconstruction and extension of the chancel. The object of cult may have been located in a decorative niche located in the northeastern corner of the church. On the opposite side, a piscina with an ogee arch was built into the wall.

Current state

The church is a remarkable example of English Perpendicular Gothic architecture, though fragments dating back to the 13th century (the west wall of the central nave) and 14th-century elements have survived (the four-light west window of the south aisle, the lower part of the tower, and the arcade under the tower, pierced in the older wall of the nave). The richness of Late Gothic detail is evident in the numerous carved corbels, gargoyles, window tracery, portals, friezes, and the inter-nave arcades. The bells of All Saints’ Church, or rather their ringing and tone, are considered one of the so-called Seven Wonders of Wales, which are the most interesting places in the country according to tradition. The building still serves as a church, but it is also open to the public.

bibliography:

Hubbard E., Clwyd (Denbighshire and Flintshire), Frome-London 1986.

Salter M., The old parish churches of North Wales, Malvern 1993.

The Royal Commission on The Ancient and Historical Monuments and Constructions in Wales and Monmouthshire. An Inventory of the Ancient and Historical Monuments in Wales and Monmouthshire, IV County of Denbigh, London 1914.

Wooding J., Yates N., A Guide to the churches and chapels of Wales, Cardiff 2011.