Historia

The abbey was founded in 1132 by Ranulf de Gernon, 4th Earl of Chester, who brought Benedictines from Savigny in southern Normandy to the Welsh-English border. The monastery became part of the Cistercian order in 1147, when the Savigny brothers merged with the Cîteaux. Ten years later, at the initiative of King Henry II, Buildwas Abbey in Shropshire was given control of the monastery. As a result, the Welsh Cistercians received significant endowments, including lands in the English county of Derbyshire. That same year, Henry II refounded the Welsh monastery and the monks moved from their original site at Hen Blâs to Basingwerk at Greenfield Valley.

In 1157, Prince Owain of Gwynedd set up a military camp at Basingwerk. Before facing king Henry II’s forces, he also intended to fortify the abbey or nearby castle with an earth rampart. The Welsh ruler stayed at the abbey because of its strategic importance, blocking the route Henry II’s army had to take. In the ensuing fighting, Owain defeated the English near Ewloe, but the peace treaty still led to unfavorable border changes. As a result, Basingwerk passed to the English and was once again occupied by Owain’s forces in 1166. In 1188, a more peaceful visit to the abbey was paid by Giraldus Cambrensis or Gerald of Wales, a monk, chronicler, linguist, and writer, traveling through Wales with the Archbishop of Canterbury to gather support for a crusade to the Holy Land. He described Basingwerk Abbey as a small, unremarkable monastic house.

In the first half of the thirteenth century, the abbey was under the patronage of Llywelyn the Great, Prince of Gwynedd. This was a period of intensive construction works on the stone monastery church and the claustrum rooms, which the prince probably supported. His son Dafydd ap Llywelyn in 1240 gave the monastery the Well of St. Winefrid with the pilgrimage chapel, thanks to which the monks used the Holywell stream to run the mill and process wool from their sheep. Later, they benefited greatly from the pilgrimage movement. In 1416 even King Henry V came to Holywell on a barefoot pilgrimage from Shrewsbury, while in 1461 another English ruler, Edward VI Tudor, paid a visit.

In the 70s and 80s of the 13th century the abbey suffered heavy losses during the Welsh – English wars. In 1284, King Edward gave a compensation of £ 100 for this reason, although the revenues of the devastated monastery were low at the end of the 13th century. The situation was improved by permits obtained from the English kings for weekly markets and yearly fairs. The king also favored Basingwerk by inviting the abbots to parliamentary sessions in London. It was one of only four Welsh abbeys that were honored in this way, although in the fourteenth century it was often in debt.

In the fifteenth century, there were disputes in Basingwerk about the appointment of the abbots. In 1430, the monastery was occupied by the Henry Wirral, a self-appointed abbot in conflict with Richard Lee, supported by the court. He ruled until 1454, when was arrested for various offenses, but soon another dispute about the abbacy flared up between Richard Kirby and Edmund Thornbar. Although the latter received the support of the general chapter, Richard held office until 1476. Calming of the situation was brought only by the rule of Abbot Thomas Pennant in the years 1481 – 1523, adored by the bards for generosity and high education.

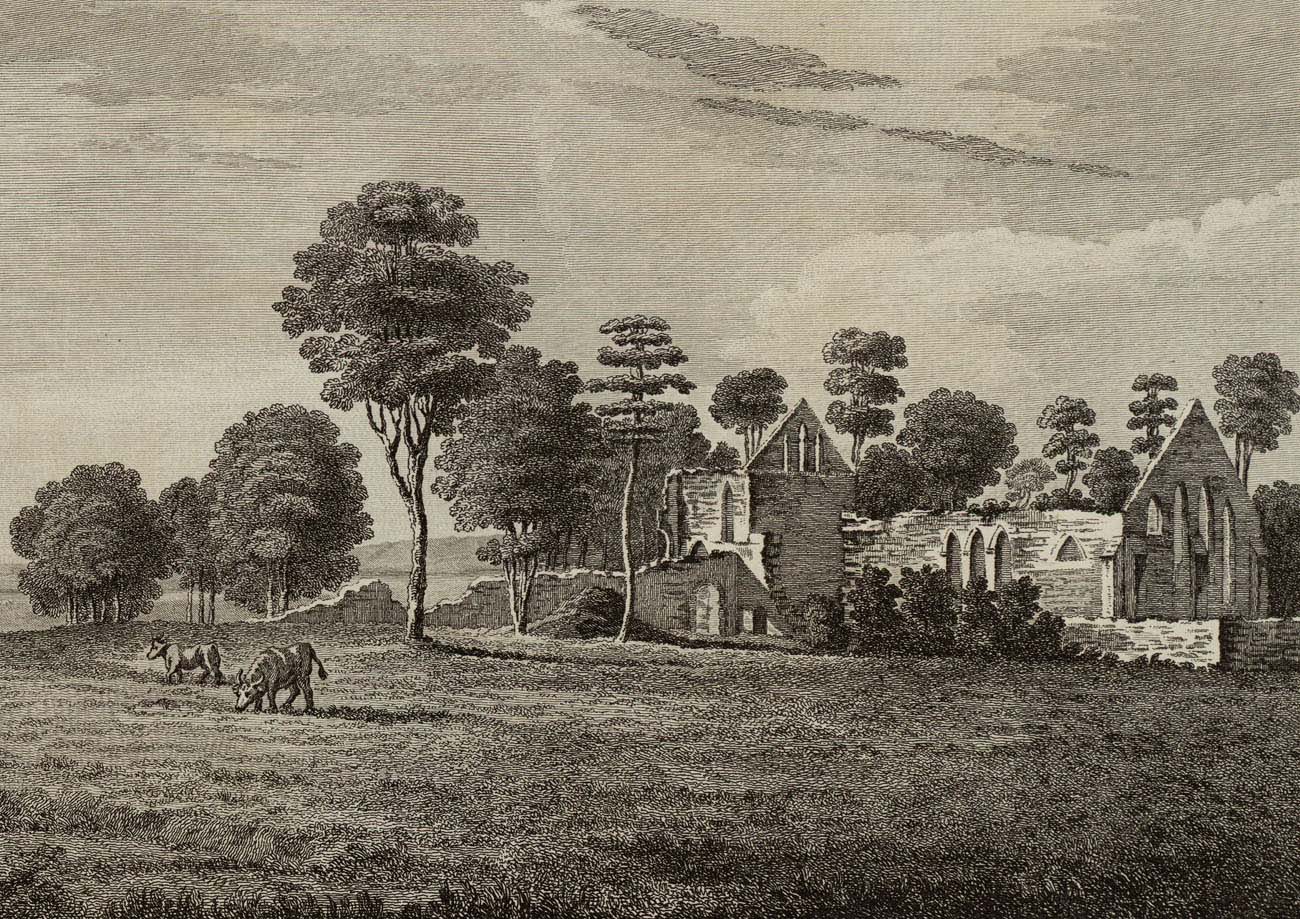

The abbey was dissolved in 1536, during the reign of Henry VIII, when only three monks were said to have lived in the claustrum. The abbey lands were granted to lay owners from the Pennant and Mostyn families, some buildings were dismantled to repair Holt Castle, and some elements were taken to Ireland for use in Dublin Castle. Furthermore, some parts of the monastery buildings may have been donated to nearby parish churches (e.g., the roof truss of Cilcain Church). The abandoned Basingwerk Abbey eventually fell into ruin and was almost completely demolished.

Architektura

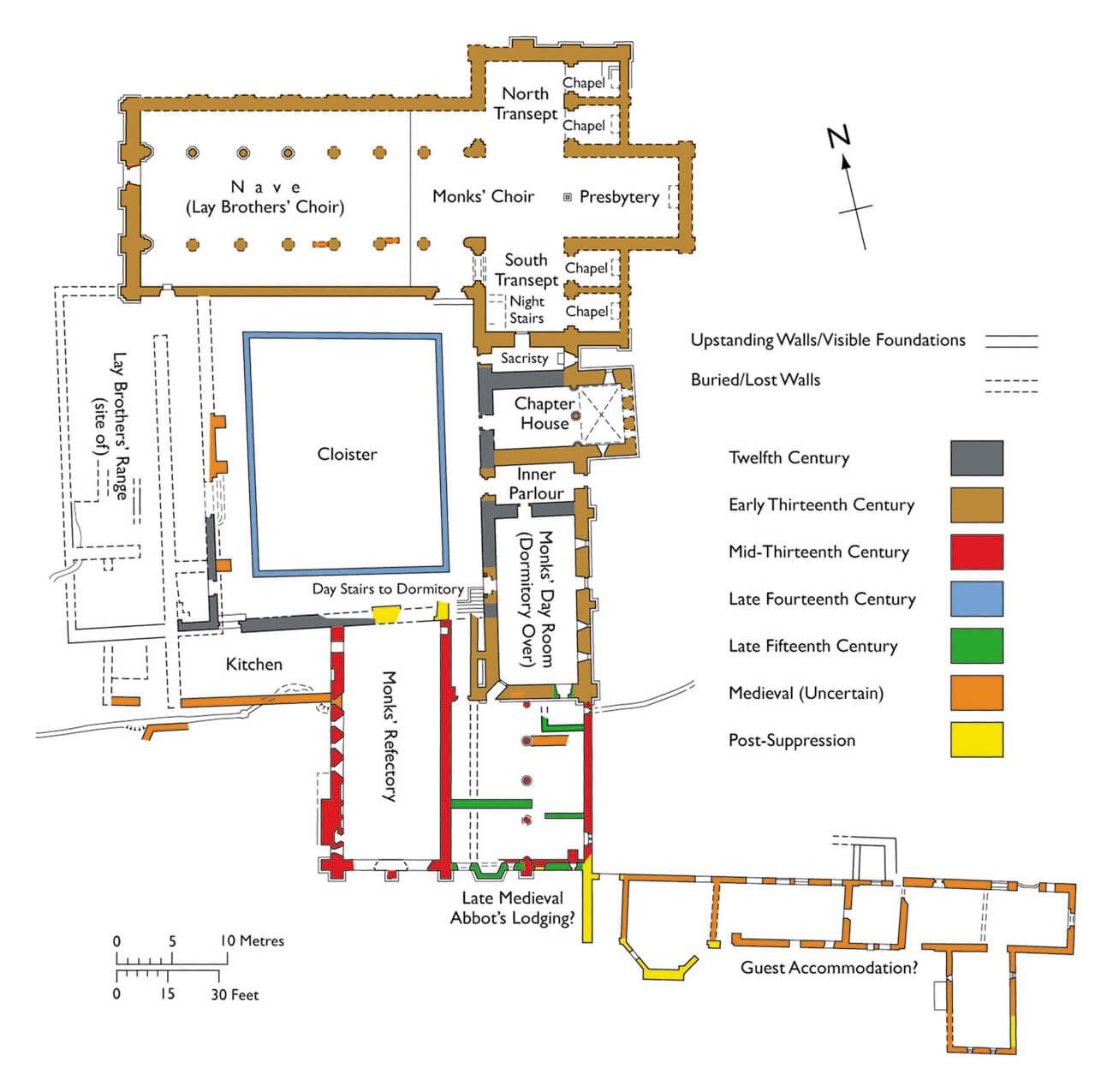

The abbey was founded on the broad estuary of the River Dee, which flows into the Irish Sea. It was situated at the northern end of a low promontory, overlooking the mouth of the Greenfield Valley to the west and the low-lying coastal areas to the north and northeast. The abbey’s plan followed the Cistercian order’s rules. The main structure was a church in the shape of a Latin cross, orientated east-west. To the south, the claustrum buildings were arranged around three sides of a large cloistered garth, measuring 28 x 23.7 meters. Further away lay the monks’ infirmary, guest quarters, and other buildings related to the abbey’s daily life and economy, located near the road connecting the abbey with St. Winfried’s Chapel to the south. The monastery must have been surrounded by a low stone wall or at least a wooden fence. The 9th-century Wat’s Dyke, originally marking the border between the kingdoms of Gwynedd and Mercia, running south from Basingwerk to the Morda Valley, may also have been used. It consisted of an earthen rampart, often reflecting the local topography, and accompanied by a ditch on the western side.

The first to be built was the church and the eastern part of the abbey buildings. It was about 50 meters long, which placed it among the smallest Cistercian churches in Wales. It was a basilica with central nave and two aisles, seven bays in the nave, with transept enlarged from the east by two pairs of four-sided chapels and with a short rectangular chancel. The main entrance to the church was located in the west façade, atypically not on the axis, but shifted to the north, between the second and third lesenes. Traditionally, the southern aisle was connected by two portals with a cloister. The western one was smaller and probably less ornate. It was used mainly by lay brothers occupying the west wing, while the larger, stepped eastern portal was used by monks. In addition, the eastern range was connected to the transept, both on the first floor and on the ground floor.

The southern transept was adjacent to a narrow sacristy (only 1.8 meters wide) behind which the chapter house was located in the ground floor of the east wing, initially in the shape of a square. At the beginning of the 13th century it was rebuilt and extended eastwards by an additional bay. East part of chapter house was separated by two arcades supported in the middle on a single pillar and crowned with a rib vault. On the south side of the chapter house there was a narrow room called parlour, that is, a place where brothers could talk freely without fear of breaking vows. The range was ended with a day room for monks, above which was a dormitory on the first floor, 19.5 meters long. A typical solution was to connect the bedroom through the so-called night stairs with the church’s south transept to allow monks to quickly reach night masses.

In the mid-13th century, a refectory was built in the south wing, oriented along the north-south axis and measuring 20.1 x 8.2 meters. Its southward projection in front of the monastery claustrum buildings was a typical feature of Cistercian monasteries, as was its proximity to the kitchen on the west side. Lighting for the refectory came from a large, pointed window on the south side and a lancet, inward-splayed windows in the west wall. The latter was thickened at the south corner and also housed a pulpit for the monk to read during meals. Along with the refectory, a large, two-aisled room was built adjacent to the east wing, forming a common façade with the monks’ dining room on the south side. This room was most likely used for utility purposes; it may also have contained latrines. Its interior and south wall were rebuilt in the 15th century, likely to make it a more comfortable residence for the abbots.

The west wing was likely occupied by the lay brothers, who had their own refectory and dormitory, necessary for the physical work they performed and the need for better nutrition, while also providing separation from the monks in the rest of the claustrum. The west wing may have been separated from the cloister by a long corridor, common in Benedictine and Cistercian monasteries. This corridor connected to the kitchen on the south, shared by the lay brothers and monks. The ground floor of the west wing likely also contained a cellarium, the convent’s pantries and storage rooms, as well as an entrance gate to the claustrum. The upper floor must have been used for the aforementioned dormitory.

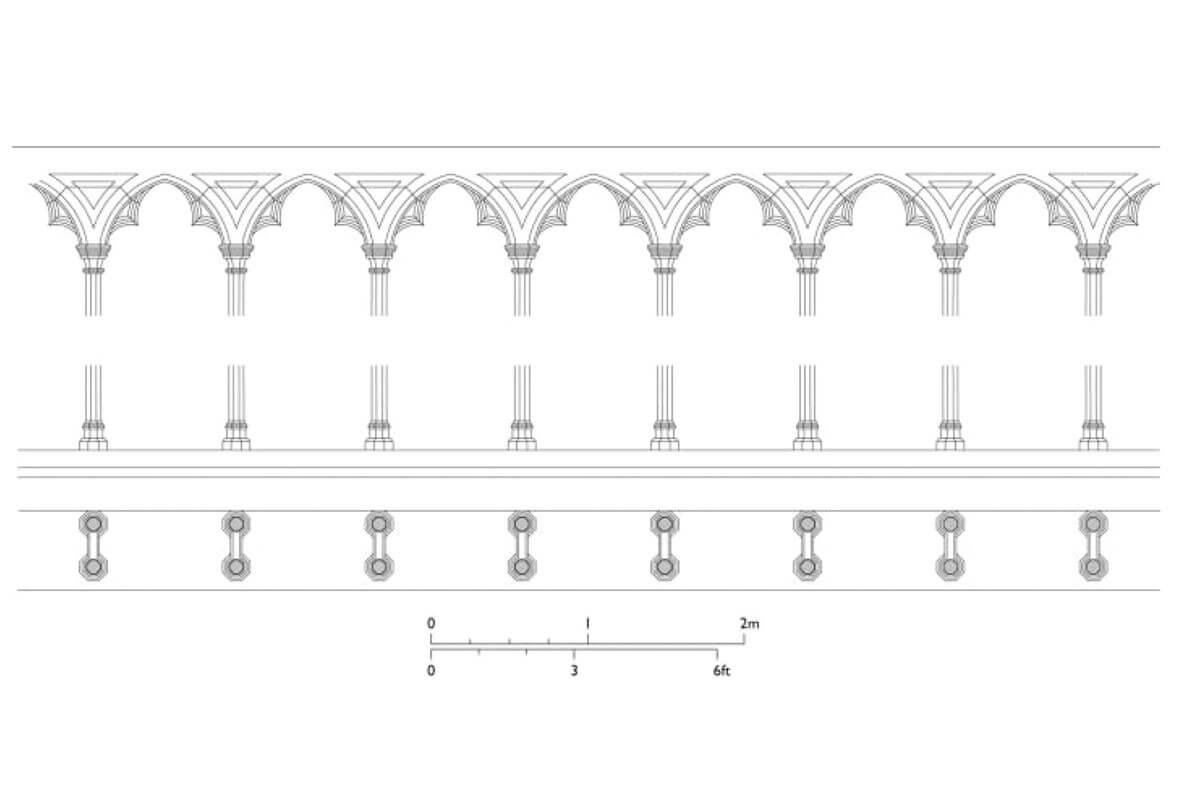

In the 14th century, new Gothic arcades were built in the cloisters. These arcades were closed with pointed arches, filled with trefoil tracery in the archivolts, and supported by pairs of octagonal columns, likely connected by sections of thin masonry (Basingwerk arcades were very similar to the cloisters in nearby Valle Crucis). At the end of the 15th century, the abbey was roofed with lead and decorated with glass windows, and new guest rooms were built on the southeast side. These ran in a series of rooms on an east-west axis, with one wing projecting southward. Originally it were likely freestanding, unconnected to the corner of the claustrum.

Current state

To this day, the building of the 13th-century refectory with ogival windows has survived in the best condition, as well as the western wall of the southern church’s transept, fragments of the east wing and rooms for the monastery guests on the south-east side. The abbey ruins are currently under the protection of the Cadw government agenda, which makes them available for visitors. During the dissolution of the abbey, some of its furnishings and some architectural elements were to be transferred to the neighboring parish churches. Among other things, the impressive late-medieval roof truss can be found today in the church in Cilcain.

bibliography:

Burton J., Stöber K., Abbeys and Priories of Medieval Wales, Chippenham 2015.

Harrison S., Robinson D.M., Cistercian Cloisters in England and Wales Part I: Essay, “Journal of the British Archaeological Association”, 159/2006.

Hodkinson E., Notes on the architecture of Basingwerk Abbey, Flintshire, “Journal of the Chester Archaeological Society”, 11/1905.

Hubbard E., Clwyd (Denbighshire and Flintshire), Frome-London 1986.

Salter M., Abbeys, priories and cathedrals of Wales, Malvern 2012.

The Royal Commission on The Ancient and Historical Monuments and Constructions in Wales and Monmouthshire. An Inventory of the Ancient and Historical Monuments in Wales and Monmouthshire, II County of Flint, London 1912.