History

The oldest fortifications in Dryslwyn, controlling one of the crossings of meandering Tywi River, were built around the second quarter of the 13th century by Rhys Gryg, ruler of the Welsh Deheubarth, or possibly by his successors. A year earlier Rhys had married into the powerful Anglo-Norman de Clare family, which strengthened his position and probably prompted the construction of the castle. Earlier, the Welsh princes did not build stone castles, new construction solutions only came with the Normans. At that time, in addition to Dryslwyn, Rhys also erected (or expanded) a very similar Dinefwr stronghold. Strengthened by his new fortifications, Rhys initially opposed Llywelyn ap Iorwerth’s decision to pay tribute to English king Henry III, which prompted the Welsh ruler of Gwynedd to join the armed expedition and bring Rhys to heel.

After the death of Rhys Gryg in 1233, his lands were divided among sons. Dryslwyn turned to younger son, Maredudd ap Rhys, while Dinefwr fell to older son, Rhys Mechyll (and after death, to his son, Rhys Fychan). In the 50s of the 13th century, a dispute broke out between them, and chaos deepened the Anglo-Norman intervention, ultimately defeated at Cymerau. In 1271, Maredudd was to die at Dryslwyn Castle, which was also the first source record of this building. When the English-Welsh war broke out in 1277, Maredudd’s son, Rhys ap Maredudd, was in alliance with Llywelyn ap Gruffyd against English king Edward I. However, this cooperation quickly collapsed, as Rhys ap Maredudd in return for keeping his lands and castles, began to seek agreement with the English. Thanks to this, he was able to develop and strengthen Dryslwyn in the next years.

The conflict between Rhys ap Maredudd and the Englishmen occurred in 1287, probably as a result of dissatisfaction of the Welshman with too little reward for withdrawing from the alliance with Llywelyn. The struggle in solitude, however, did not turn out to be a good move, because in August 1287 Dryslwyn besieged over 11,000 people under the command of Edmund, Earl of Cornwall. After the fierce battles, during which both siege engines and mining were used, which collapsed a fragment of the wall that killed several knights inspected the attack, including Nicholas, Baron de Stafford, Sir William de Monte Caniso and Sir John de Bonvillars. The castle garrison surrendered on September 5, 1287. Rhys escaped but was deprived of his property and captured in 1292. Transported to York, he was brought to trial, accused of betrayal and executed. After the capture, Dryslwyn was handed over to Alan Plukenet, who made the necessary repairs and expansion of the castle.

For the rest of the 13th century, Dryslwyn Castle remained under the control of English kings, carrying out periodic repairs and minor reconstructions. In 1316, it was attacked during the Welsh uprising, but avoided significant damages. The following year Edward II gave the castle to his unpopular favorite, Hugh Despenser, which caused another attack by the English lords in 1321, who could not bear the widening influence of the Despensers. The castle was restored to the Crown in 1326, after the overthrow of Edward II and the Despensers family. In the mid-fourteenth century, it was already neglected and was in a bad condition.

During the Welsh uprising of Owain Glyndŵr from 1403, the castle was surrendered to the rebels by then constable Rhys ap Gruffudd. In 1409, the forces of Henry IV recaptured the stronghold, but at the same time the decision was made to leave the fortifications, partly demolishing the castle walls. Since then, the abandoned castle fell into disrepair.

Architecture

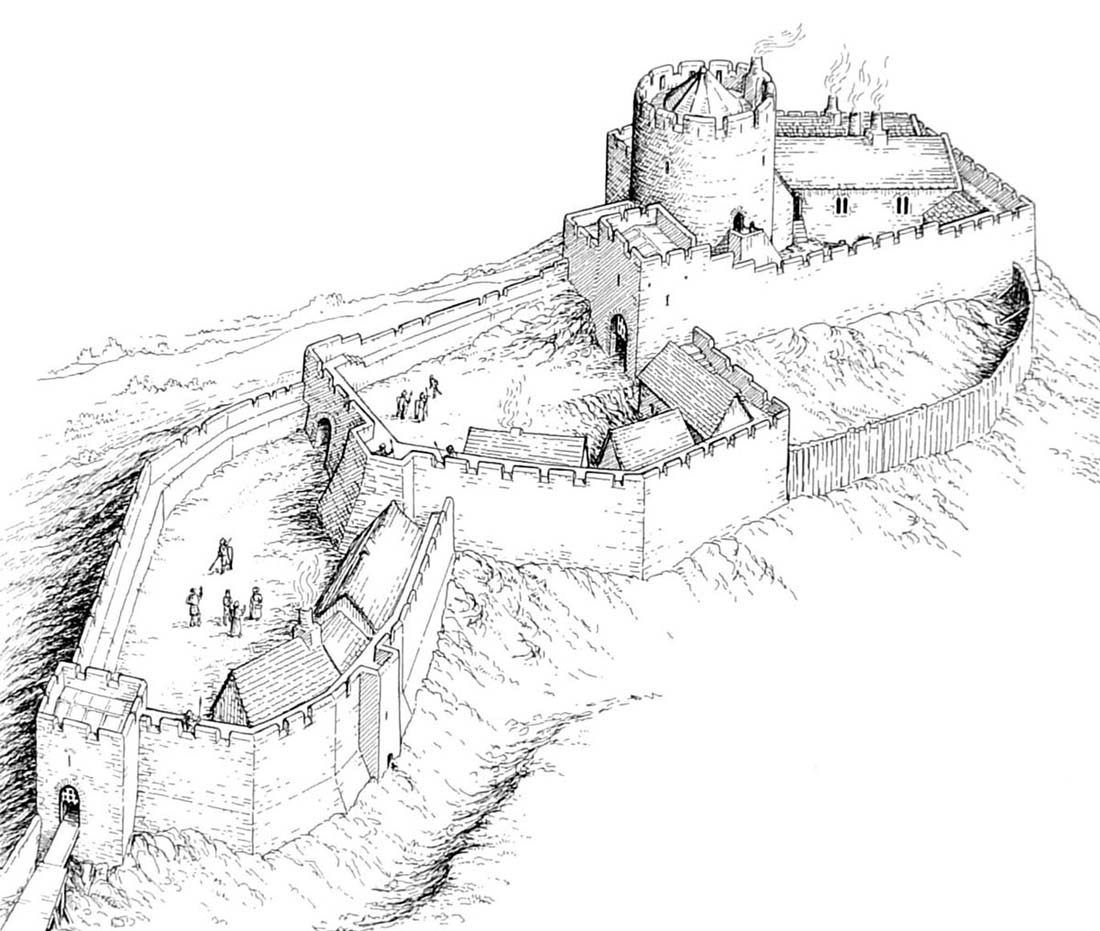

The castle was erected from limestone on an easy to defend top of a rocky hill overlooking the Tywi Valley. The high and steep slopes descending towards it secured the castle all over the southern side. Also on the western and partly northern sides the escarpments were inaccessible, and the only more convenient approach was possible on the milder descending at north-eastern part of the hill.

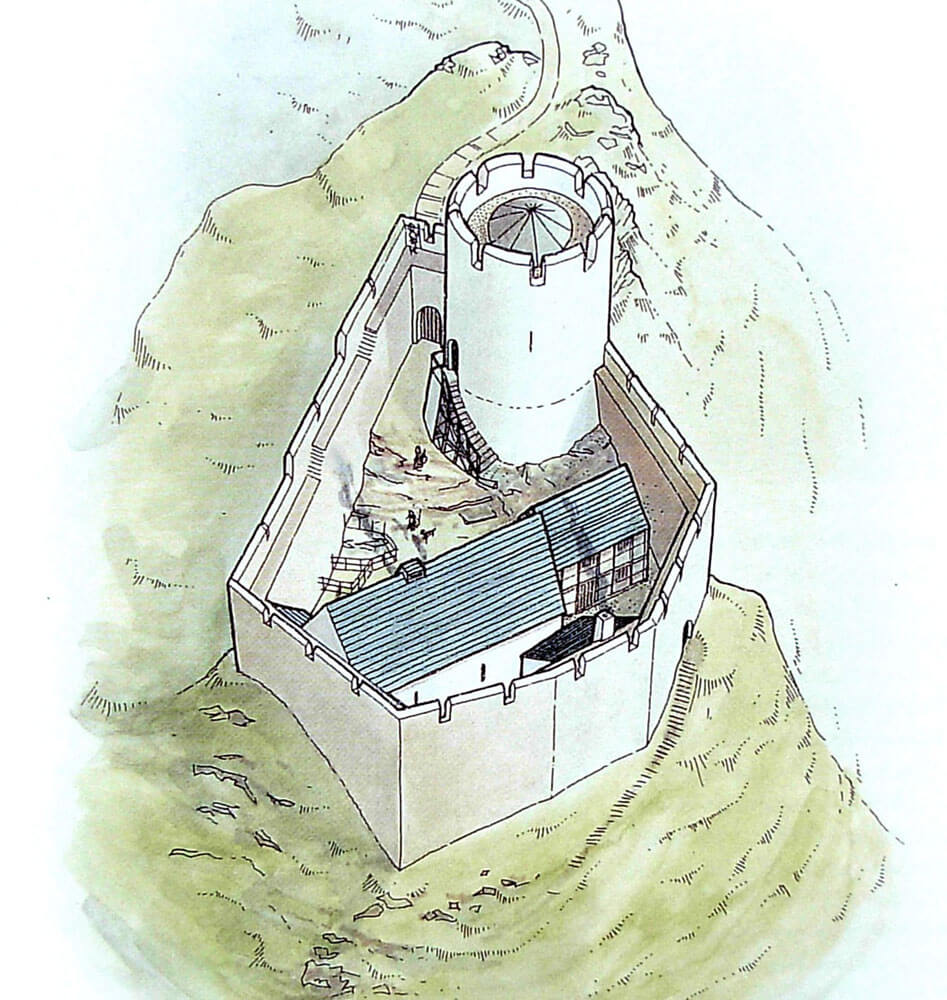

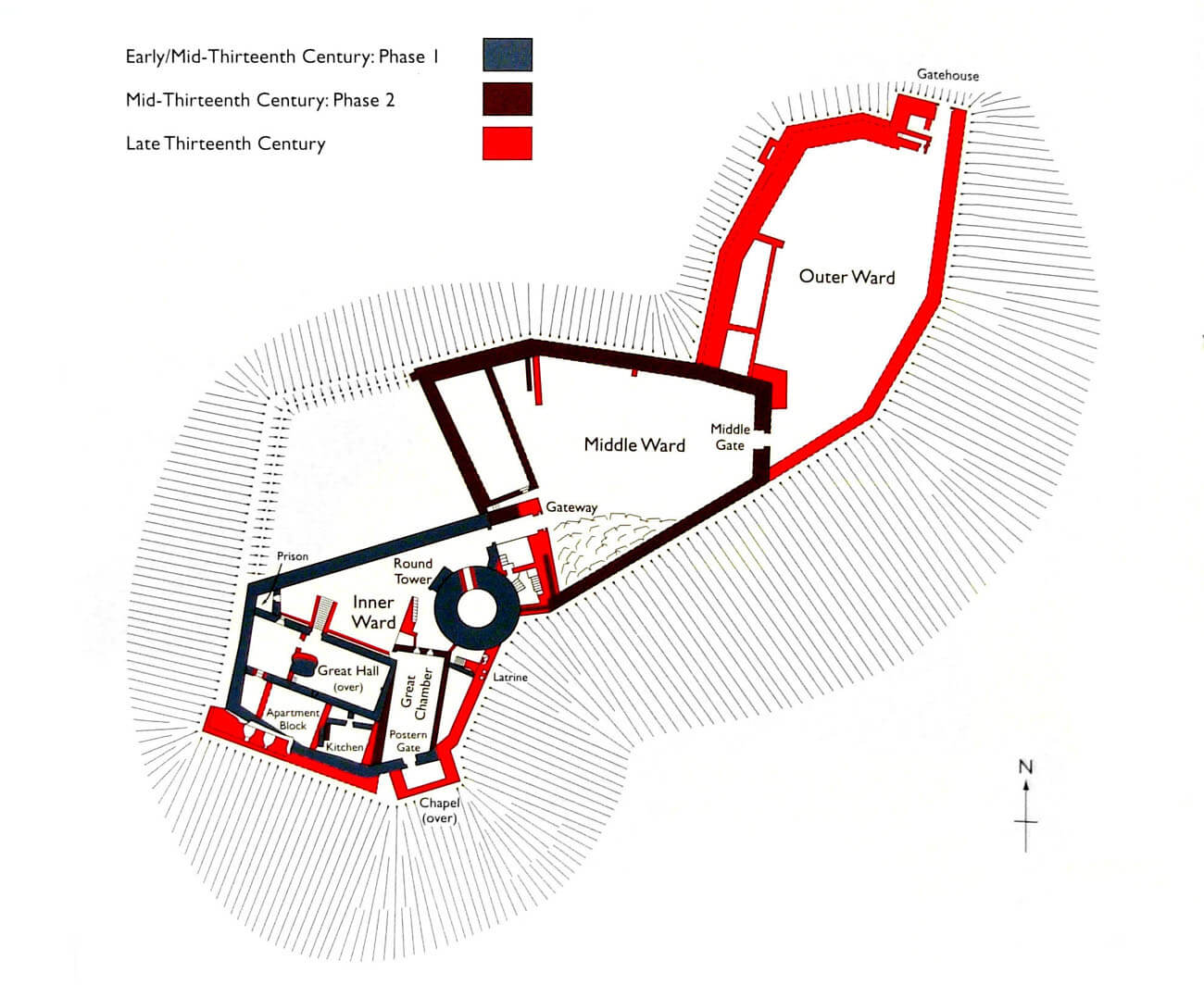

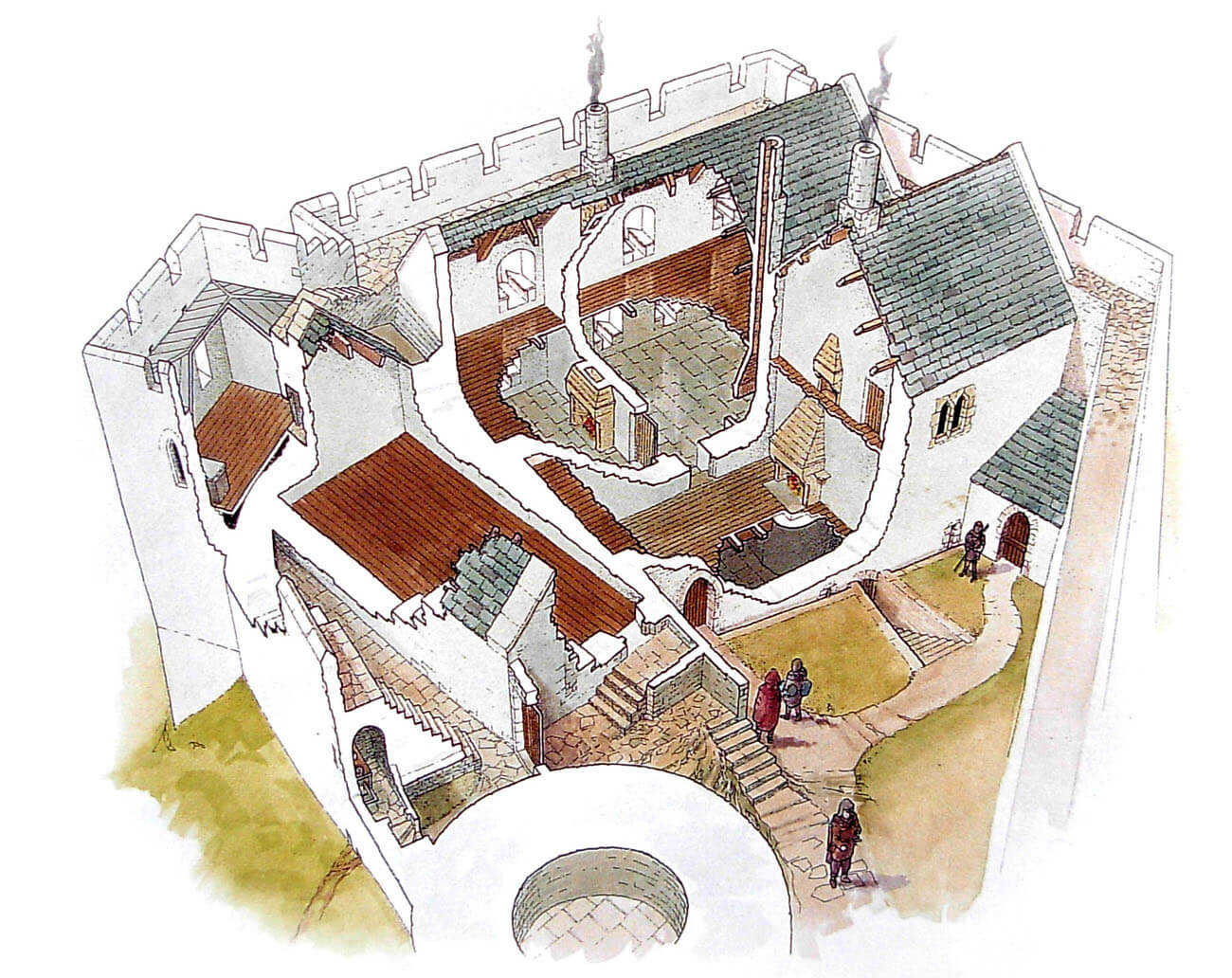

The earliest building from the second quarter of the 13th century consisted of defensive walls situated in the highest place, erected on the shape of an irregular pentagon with a cylindrical tower – a keep, about 12 meters in diameter, on the eastern side. Its walls in the lower part were up to 3 meters thick and were slightly widened in relation to the upper parts (as in Dinawfr, Skenfrith and other Welsh-English keeps). Originally it had at least two floors above the basement and wooden stairs to the first floor level from the north-west. In this place there was a small widening in the form of a buttress to which the stairs were attached. They could have been easily dismantled in the event of a possible threat and the desire to cut off the keep from danger. The lower floor was originally reached through an opening in the first floor. This dark room with a stone-paved floor served only as a warehouse and a pantry, possibly as a prison. Later, probably in the fourteenth century, a new portal was pierced into the basement directly from the courtyard.

The internal development of the small courtyard was a rectangular great hall building and a small stone kitchen building, both located in the southern part of the castle. The great hall was on the first floor, above the ground floor, whose massive pillar supported the hearth at the top and the wooden ceiling. In the 1280s, the great hall was rebuilt: the lower floor was lowered, and an additional floor with a flat ceiling was created. A transverse wall also separated the western part of the building in which two floors were created. At that time two entrances led to it: a portal from the north on the ground floor level and stairs down to the basement. A stone groove was created at the base of the building’s wall, serving as a drain for rainwater flowing from the entire courtyard. The other economic buildings grouped in the eastern part of the courtyard were originally timber. In the north-west corner, between the building of the great hall and the perimeter wall, there was yet a small structure, probably used as a prison. Its chamber was recessed below the level of the courtyard, and the door opened outwards.

In the mid-thirteenth century, Rhys ap Maredudd expanded the outer ward on the north-eastern side (later the middle ward) and strengthened the entrance gate to the upper castle. Initially, it was an ordinary doorway in the wall, closed by a bar and flanked by a keep. Due to the slopes of the hill, it was reachable from the outside on stone steps. After the extension, an unroofed foregate with a portcullis and a door was added. The portcullis was lowered in stone guides, while the door was mounted on iron hinges placed in holes in the wall. From the south, the foregate was adjacent to a small stone platform formed of a short section of the wall connecting to the main perimeter and the keep. On it were discovered relics of a small fourteenth-century half-timbered building, probably a place from where the guard could control entering the castle. A blocked window opening suggests that earlier, probably before 1287, a stone building was in its place. In addition to the watchtower, there were also stone stairs leading to the platform and to the crown of the defensive walls. One of the stairs led from the defensive wall-walk, probably straight to the adjacent cylindrical tower, others to the upper part of the foregate, where the portcullis mechanism had to function.

Rhys ap Maredudd also rebuilt the buildings in the upper ward in the mid-thirteenth century, adding a new wing (great chamber) in the east, perpendicular to the great hall. It received two floors separated by a flat ceiling, and its southern wall was oblique, as it was part of the perimeter wall. There used to be a small postern gate in it, accessible after a few stairs created in a clay ground. On its outer side there was a platform ensuring a descent down the hill and further to the crossing on the river. With the construction of the east wing, it probably ceased to be used.

In the later years of the 13th century, the perimeter walls on the southern side were raised and strengthened, a four-sided tower with a chapel was erected, and a number of living rooms that filled the space between the great hall and the southern wall was created. As a result of these works, virtually the entire courtyard was built, only a narrow space on the north remained. The remaining elements of the upper ward were latrines on the eastern side, by the keep. They were inserted into the rebuilt eastern curtain of the wall, where it was reachable by means of a short spiral staircase. Two chutes with outlets directed down the hill had stone superstructures with wooden seats.

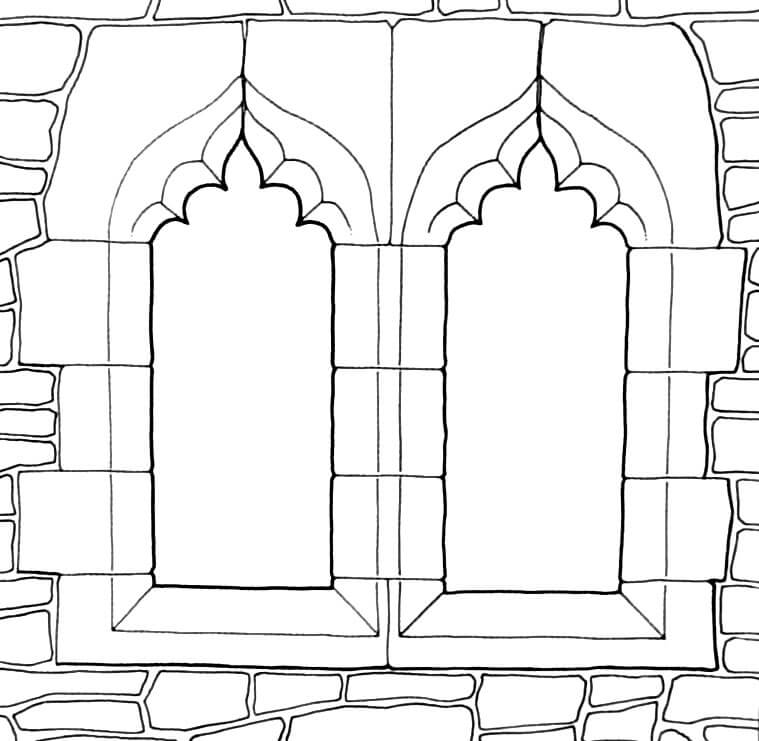

The southern wing of the second half of the 13th century housed living quarters on two floors separated by a flat, wooden ceiling, while its lower floor was on the same level as the central floor of the great hall after rebuilding. The building’s lighting was provided by large windows facing the Tywi Valley, cut into the thickened southern wall, flanked by side benches located in niches. The division into chambers was provided by two transverse walls, with the easternmost chamber occupying the area of the previous, free-standing kitchen and perhaps took over its function. The tower with the chapel had the form of a quadrangle situated in front of the perimeter of the walls, on the platform previously housing the entrance to the postern gate. Its walls at the upper level were pierced with three lancet windows.

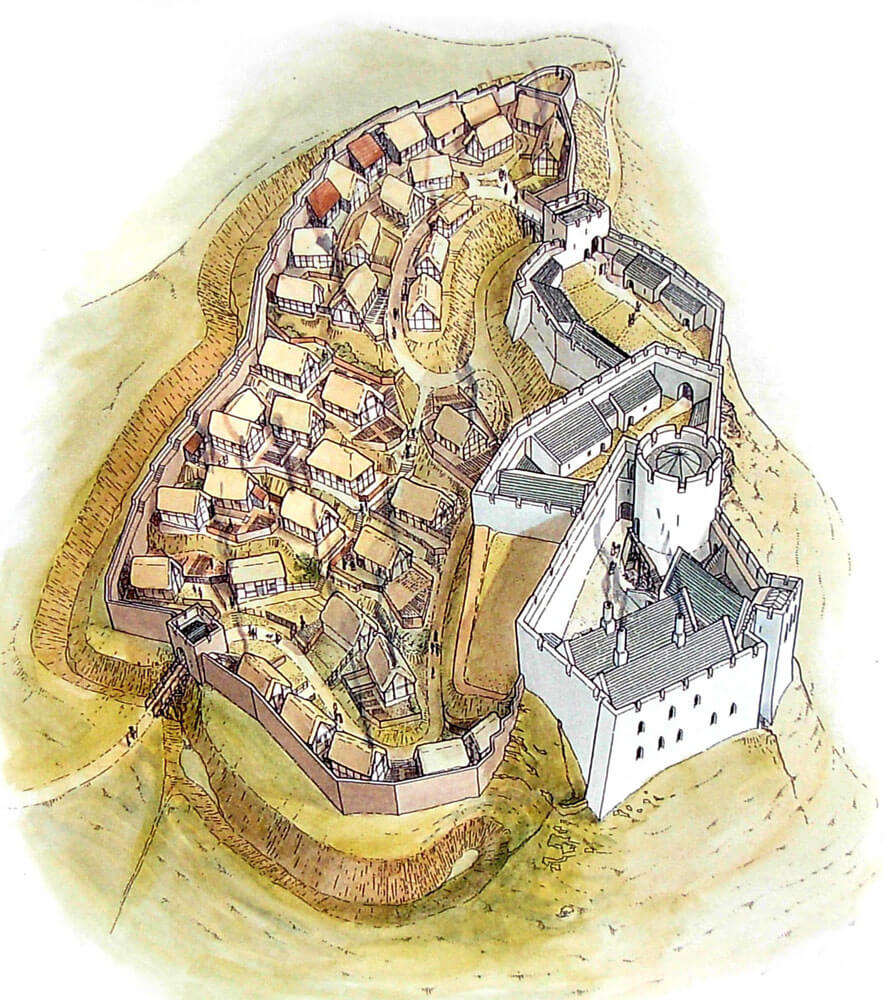

The middle ward had an irregular form similar to a pentagon made of short, straight sections of the wall. No traces of the lower gatehouse were found, so the entrance had to be a regular portal opened in the eastern wall. It was flanked from the north by a significant thickening of the wall, probably created after the siege of 1287. In the crown of this thickening there could be a defensive platform, giving the whole look similar to the tower. The oldest internal development was made up of an oblong building in the western part of the courtyard, traces of basement houses from the end of the 13th and the beginning of the 14th century were also discovered at the northern wall. The remains of ceramics found indicate its residential and economic functions. The gate to the upper castle was preceded from the south by a rocky elevation, originally slightly higher, but reduced during the English occupation.

At the end of the 13th century, another north-eastern ward (lower castle) was built, fortified with a 1.8-meter-thick stone defensive wall, preceded by a ditch from the north. The entrance led through a four-sided gatehouse from the north. It had only two floor, with the lower gate passage accessible on a timber bridge (perhaps a drawbridge) over the ditch. The passage itself was secured by two portcullises and two doors, placed in a set portcullis plus a door at both ends of the gate. At the back of the building, the vaulted corridor led up the stairs to the upper floor room, where there were probably mechanisms supporting the portcullises. The courtyard of the lower ward was built up with economic houses (stables, warehouses, granaries, garrison quarters), located at the inner faces of the defensive walls. A large building stood out from the west of the outer ward, but its purpose remains unknown.

On the northern side of the castle, at the foot of the hill, a small town developed, protected by a ditch 5 meters wide and about 2.5 meters deep, and a defensive wall into which the west gatehouse led. It probably had two floors with a small guard room above the gate passage, closed with a portcullis and wooden door. The stone fortifications of the town were erected at the end of the 13th century, in the 1280s on the initiative of Rhys ap Maredudd or by the English after conquering it in 1287. Within the town in the first half of the fourteenth century there were at least 34 houses, as well as granaries, pantries and other economic buildings for animals. The houses were small constructions, 10-11 meters long and 4.6 meters wide. In the lower part they were made of stone, above half-timbered (the wooden frames were filled with wattle and clay, and the whole was probably whitewashed to protect against water), while the floors were made of beaten clay, and the roofs were covered with thatch or shingle.

Current state

The largest of the castles erected by native Welsh people is today a poorly preserved ruin. Only the south-west corner with the south wall has survived from the castle, in which remains of windows and fragments of a four-sided tower, originally housing the chapel, are visible. The remaining buildings show only the foundations reaching in the highest places up to a few meters, uncovered during archaeological excavations. The ruins are under the care of Cadw and are open to the public.

bibliography:

Caple C., Rees S., Dinefwr Castle, Dryslwyn Castle, Cardiff 2007.

Davis P.R., Castles of the Welsh Princes, Talybont 2011.

Davis P.R., Towers of Defiance. The Castles & Fortifications of the Princes of Wales, Talybont 2021.

Kenyon J., The medieval castles of Wales, Cardiff 2010.

Lindsay E., The castles of Wales, London 1998.

Salter M., The castles of South-West Wales, Malvern 1996.