History

Dinefwr was built on a hill above the River Tywi, an important waterway that served as the main communication artery. The earliest reliable record of castle dates back to the mid-12th century, when Welsh chronicler Brut Y Tywysogyon reported that Dinefwr was captured by Rhys ap Gruffydd (Lord Rhys) in 1165. He was the ruler of Deheubarth, an area stretching out in south-west Wales, a ruler strong enough to resist Anglo-Norman aggression, probably he also contributed to the erection of the first stone fortifications in Dinefwr.

The death of Rhys ap Gruffydd in 1197 caused that a furious dispute over the right to inheritance arose between his sons and grandchildren. Dinefwr Castle was repeatedly taken over by the pretenders, among others as a result of the siege and assault in 1213, and the dispute lasted until 1216, when the superior prince Llywelyn ap Iorwerth forced a family settlement. The castle was given to Rhys Gryg, one of the sons of Rhys ap Grufford. He got married to the powerful Anglo-Norman de Clare family and most likely made upgrades at Dinefwr. Rhys opposed Llywelyn ap Iorwerth’s decision to pay tribute to king Henry III, which resulted in the siege of Dinefwr and surrender of Rhys. The castle was then partially demolished, probably as part of an agreement between the prince Llywelyn and Rhys Gryg. It is not known what scale the demolition has achieved, but Rhys’s subsequent long reign meant that he had a lot of time to rebuild or build new fortifications.

After Rhys Gryg’s death in 1233, his lands were divided between the heirs: Maredudd ap Rhys, who obtained Dryslwyn, and Rhys Mechyll, who received Dinefwr and Carreg Cennen. When Mechyll died in 1244, the castle was taken by his son Rhys Fychan. Fychan temporarily lost Dinefwr to the English due to the support of Dafydd ap Llywelyn, Prince of Gwynedd, but regained it in 1248 after recognizing the jurisdiction of the English king in Carmarthen. In 1256, prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd as a result of subsequent inter-Welsh disputes, together with Maredudd, invaded the lands of Rhys Fychan’s Ystrad Tywi, completely depriving him of his patrimony. The chaos in the country was deepened by the Anglo-Norman intervention in favor of Fychan, finally defeated at Cymerau. Not for long, however, Fychan was disinherited, because Llywelyn, looking for a normalization of relations, returned Dinefwr to Fychan, which angered Maredudd, who was finally imprisoned by Llywelyn on charges of disloyalty three years later and spent three years in a dungeon at Criccieth Castle. In 1271 both Maredudd ap Rhys and Rhys Fychan died, and Dinefwr received Maredudd’s son, Rhys ap Maredudd.

As a result of the Welsh-English war of 1277 and the war campaign of King Edward I, the forces of the last Welsh supreme prince Llywelyn ap Gruffydd were defeated and the rulers under him, including Rhys ap Maredudd, surrendered to the English power. Despite this, Rhys was denied of Dinefwr Castle, which was confiscated and entrusted to the Justicar of West Wales, Bogo de Knovil. Disappointed, he got into conflict with the next English Justicar, Robert de Tibetot in the 1280s, and in 1287 he even attacked and captured Dinefwr and the Carreg Cennen and Llandovery castles. The English answer was fast and strong. The eleventh-thousand army under the leadership of a king’s cousin, Earl Edmund of Cornwall, recaptured all strongholds. Rhys himself, despite being able to escape and continue his resistance, was captured in 1292 and executed in York on charges of treason.

For the rest of the 13th century Dinefwr remained the royal castle, managed by John Giffard, and from 1310 by Edmund Hakelut. Numerous repairs were made than and it was expanded. Castle was attacked during the Welsh uprising in 1316, but avoided significant damages, and the following year king Edward II gave it to his unpopular favorite, Hugh Despenser. This resulted in another attack in 1321 of the English marcher lords, who could not bear the expanding influence of the Despensers and joined the revolt led by Thomas, Earl of Lancaster. This rebellion was suppressed and the castle returned to the royal favorite. Eventually, however, in 1326 it was restored to the Crown, after the overthrow of Edward II and the fall of the Despensers family.

In 1403, the Dinefwr castle was attacked by the Welsh rebels of Owain Glyndŵr, but the siege was unsuccessful. Despite the low castle garrison and small supplies, the attackers withdrew after ten days. The stronghold remained in the hands of the English, and when the revolt ended, it was repaired. At the end of the fifteenth century, the castle was in the possession of Sir Rhys ap Thomas, who carried out its rebuilding. In 1531 his grandson, Rhys ap Gruffydd, was executed for treason, and the castle was confiscated by the Crown, though later the family could get it back. In the seventeenth century, the cylindrical keep of the castle was partially modified for a summer residence, but after the fire of the eighteenth century Dinefwr was eventually abandoned.

Architecture

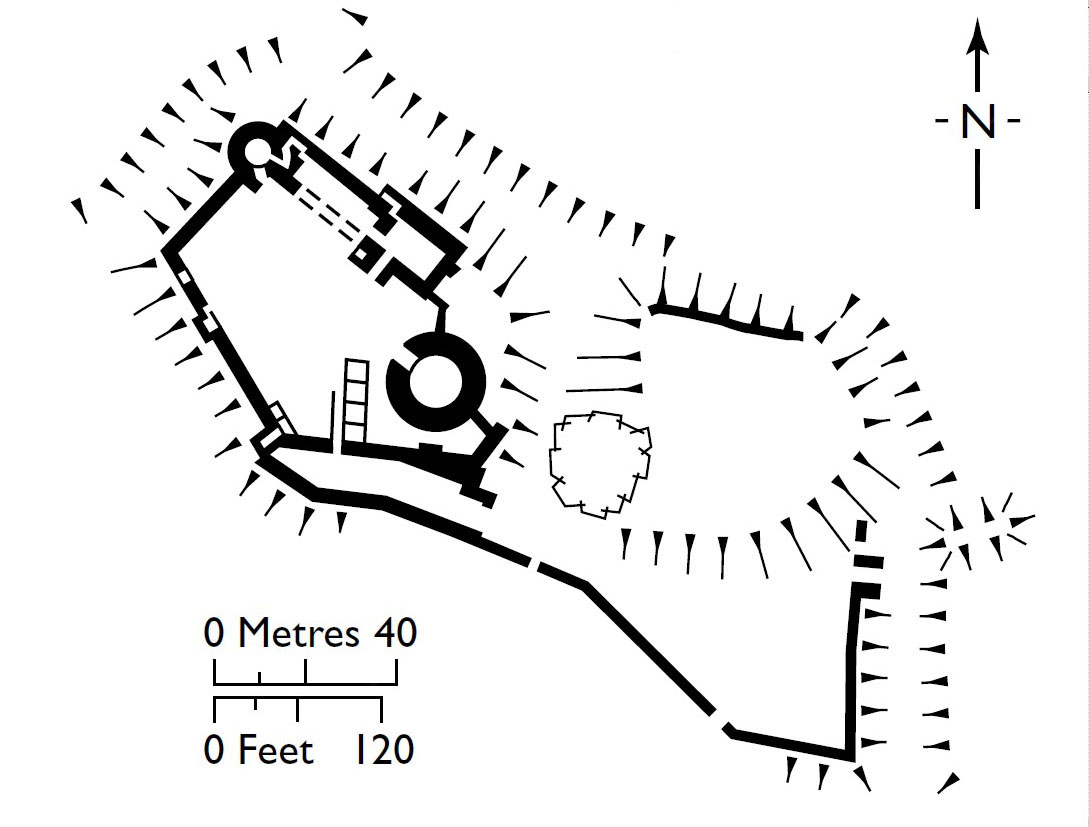

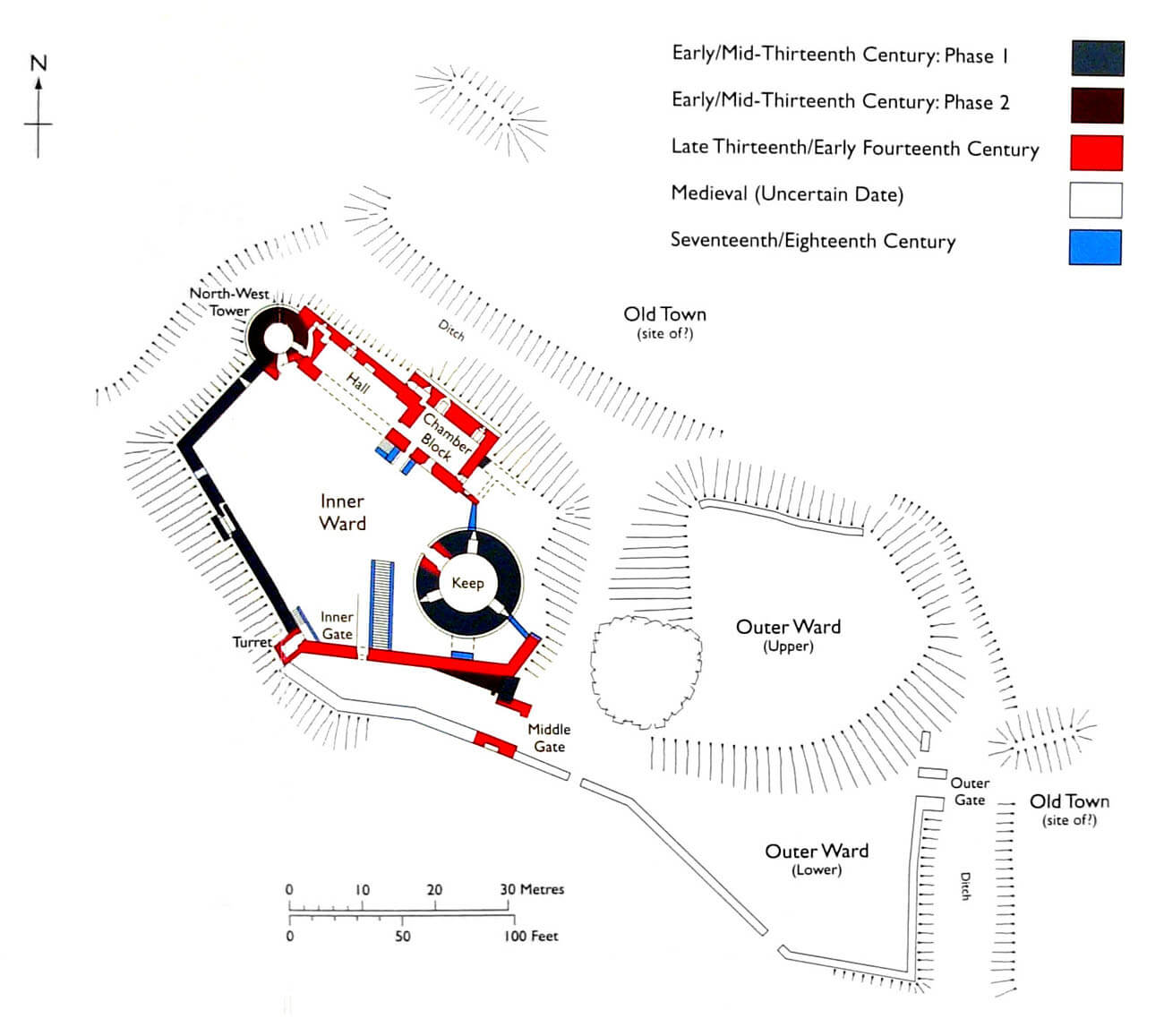

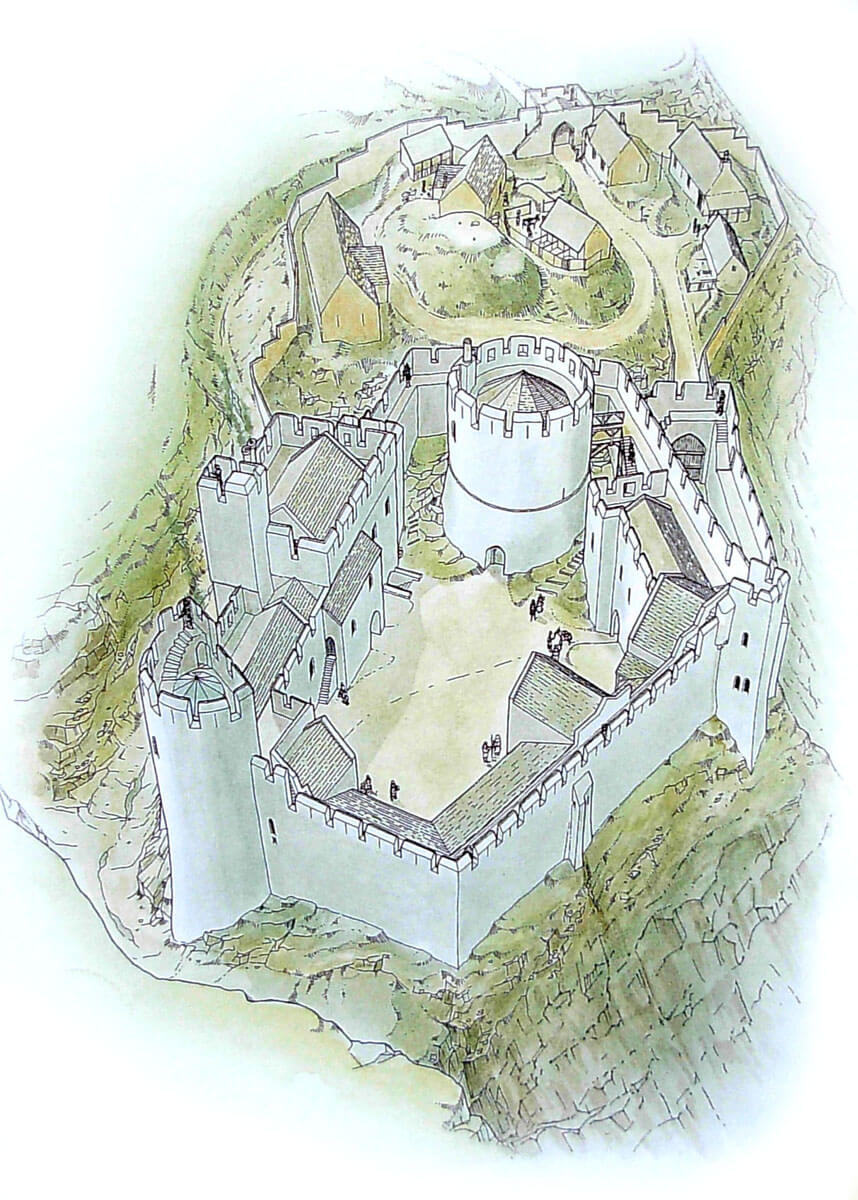

The castle was situated on a hill, in a bend of the Tywi river flowing around it from the west, south and east. The slopes of the hill provided protection mainly from the south, so the approaches from the other directions were secured with a wide ditch on the eastern side (where there was an entrance to the outer bailey), reaching about 15 meters. A ditch of a similar width separated the outer bailey from the main part of the castle.

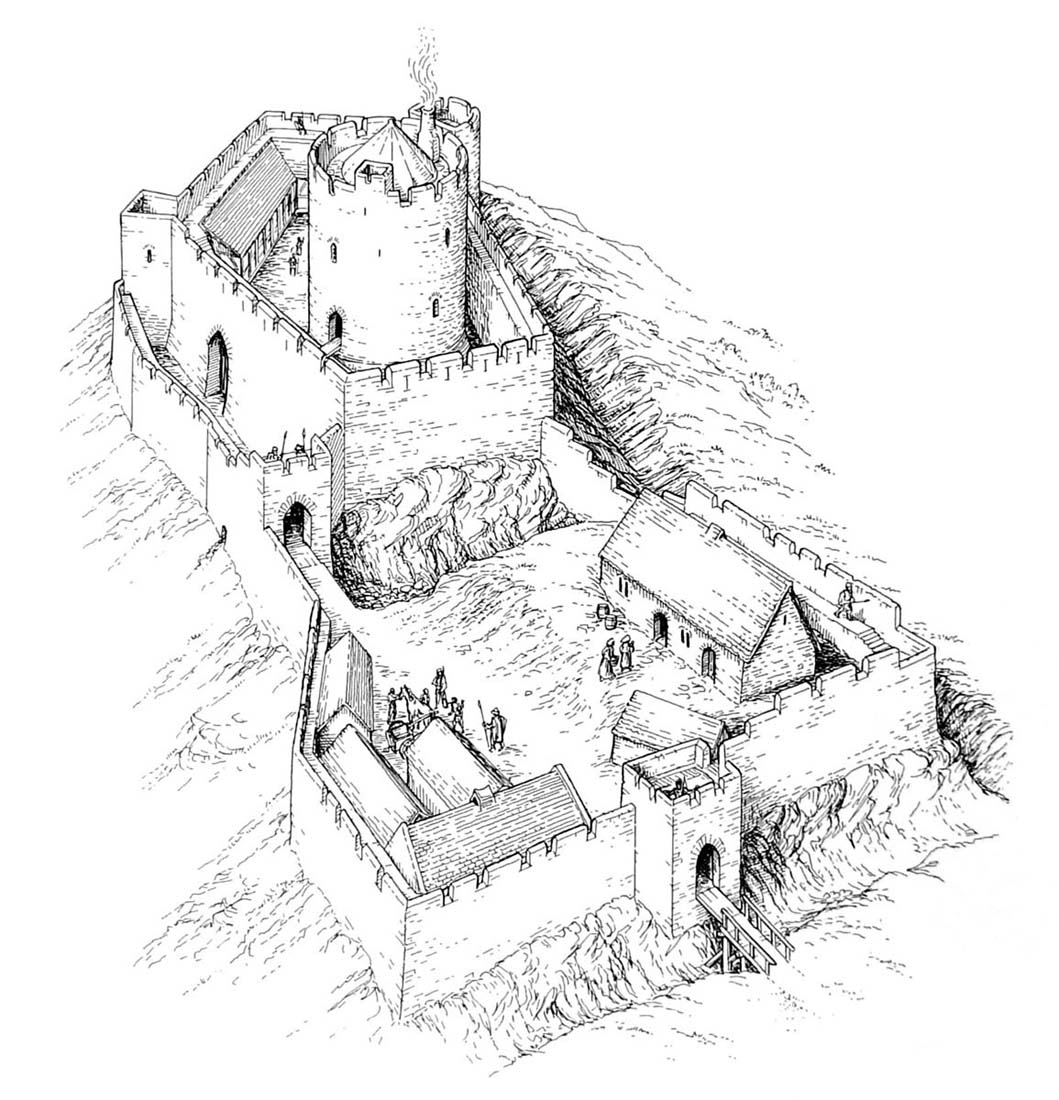

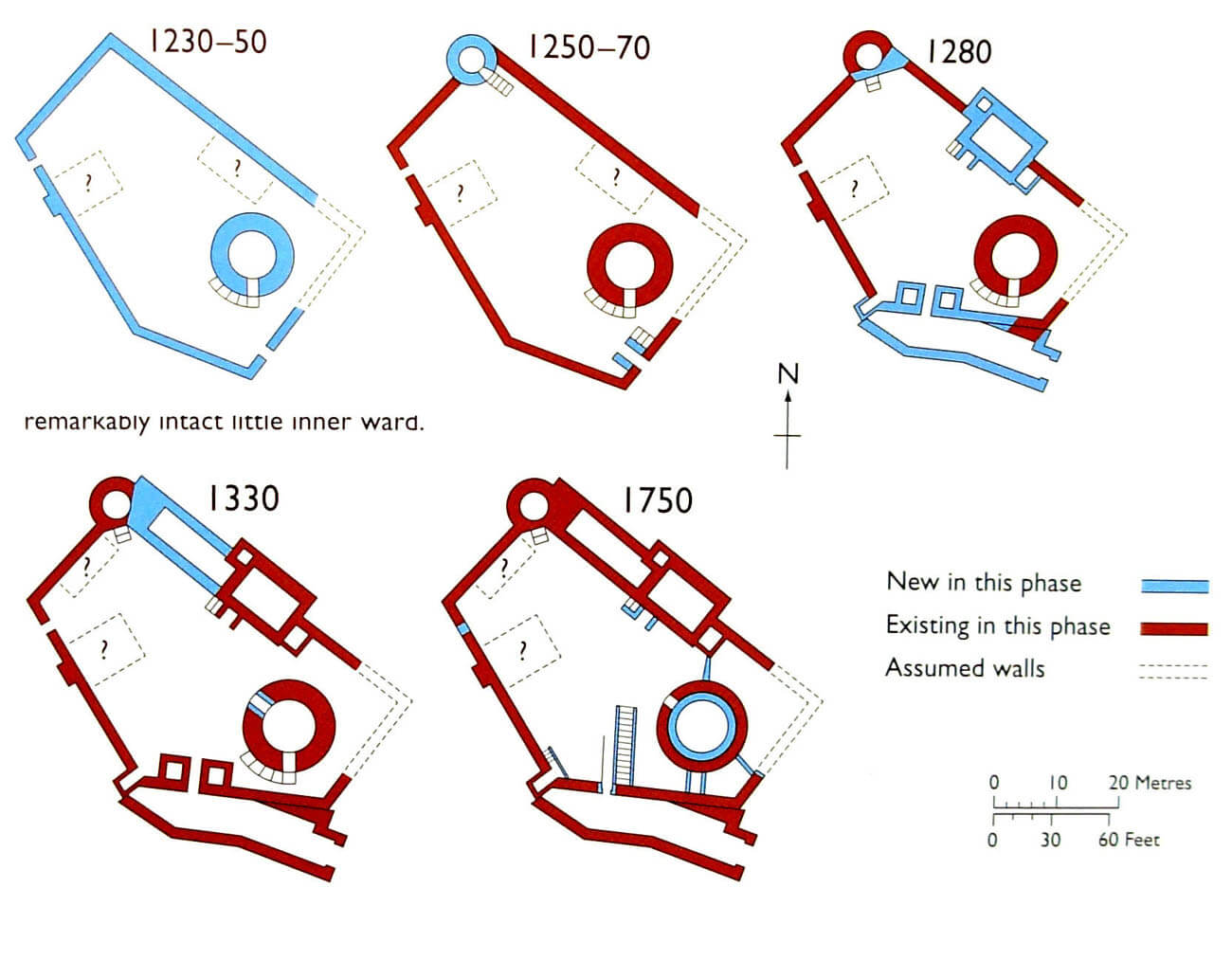

In the first half of the 13th century castle consisted of a pentagon of defensive walls 1.8 meters thick, separating a courtyard measuring approximately 50 x 28 meters, and a massive, cylindrical keep with a diameter of 13.5 meters and walls 2.6 meters thick, located on the south-eastern part of the courtyard. Due to the seventeenth-century reconstruction, it is not certain what height originally the keep was, maybe only the ground floor and the first and second floors, as in preserved similar constructions. It received a cylindrical form with a widened (buttressed) bottom part, with the width change emphasized by a roll moulding. The original entrance to it was on the first floor, only in the fourteenth century the portal on the ground floor was pierced. Originally, the entrance to the lowest floor could only be through a hole in the floor of the upper floor. The light was supplied only by three slits on the first floor and small windows in the upper parts, flanked by side seats. The ground floor was completely devoid of sunlight.

The remaining internal buildings of the castle were probably of wooden or half-timbered construction and attached to the inner walls of the perimeter walls, although some stone buildings cannot be ruled out, especially in the northern part of the courtyard. At the south-western perimeter wall a latrine bay was placed with the entrance pierced in the wall thickness. The original gate was an ordinary portal in the wall, located on the south-east side, in close proximity to the keep who protected it. Around 1250-1270, it was reinforced with a gatehouse, atypically placed entirely on the inside of the perimeter, at the inner courtyard. It was preceded by the aforementioned ditch, which was not necessary only on the southern side, where the slopes steeply descended towards the Tywi river valley.

In the Welsh period, probably at the beginning of the second half of the 13th century, a smaller north-west cylindrical tower about 7 meters in diameter was also built in the castle. It probably served only for defense and watch purposes, because it lacked a fireplace and latrine. In the second half of the thirteenth century, the tower was rebuilt, perhaps due to damages during the siege. Its round wall from the side of the courtyard was then replaced by a straight wall. Probably in the first half of the fourteenth century, after adding the adjacent building, the tower received a new entrance through the stairs from the courtyard level, operating next to the older entrance, providing access from the crown of the defensive wall.

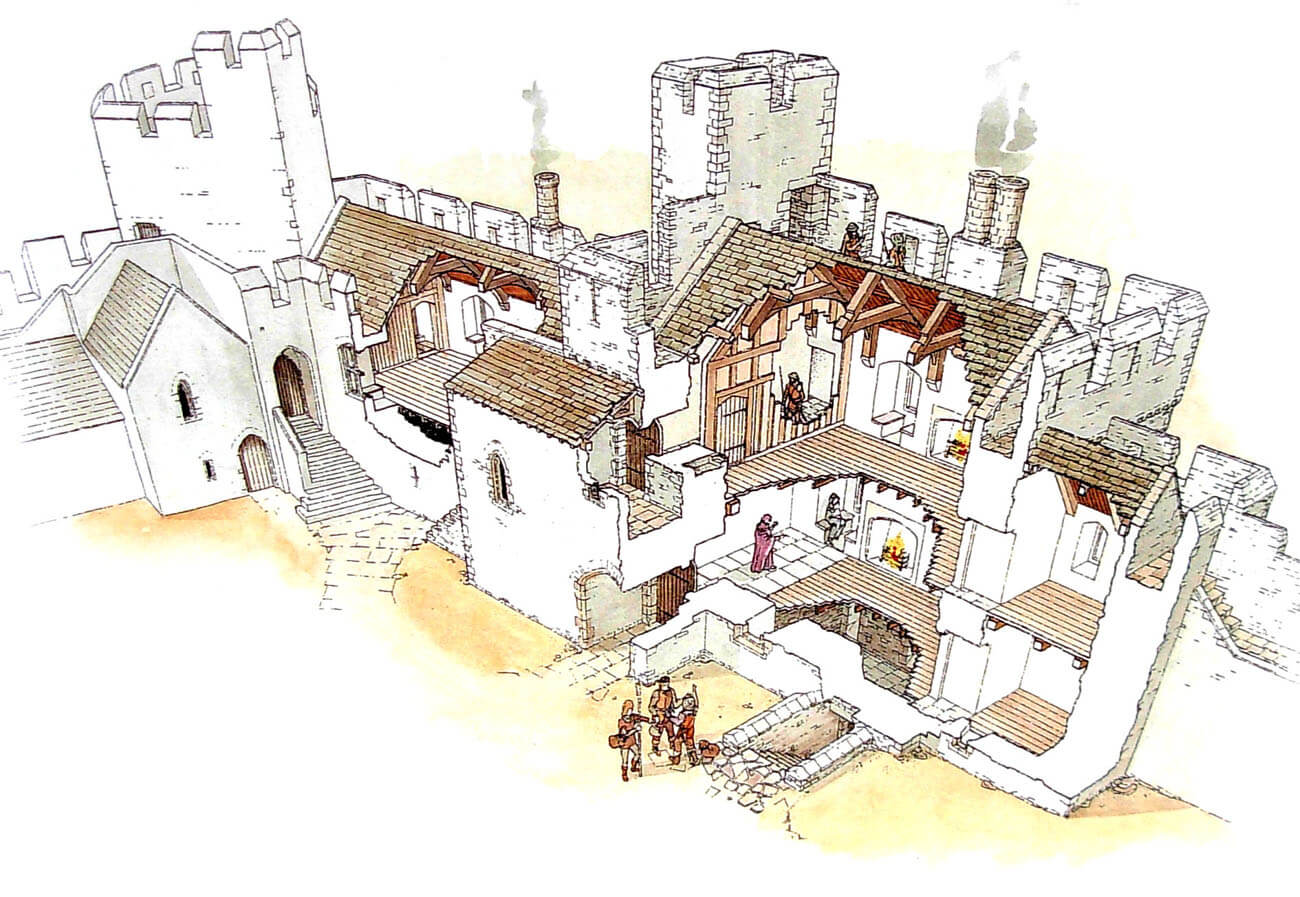

After the English capture, the castle was significantly expanded in the late 13th century. On the north side of the courtyard a quadrangular building was erected, partially extended beyond the perimeter of the wall. It had a basement with two upper floors, originally had small gothic windows (probably enlarged yet in the Middle Ages), as well as a passage to the adjacent, four-sided latrine turret. On the high ground floor and first floor there were probably large residential chambers, separated by wooden ceilings (set on stone corbels) and warmed by fireplaces. The windows facing north were equipped with side stone benches in quite deep niches and closed with wooden shutters. Smaller rooms could also be located on the eastern side in a no longer existing extension. The basement was accessible via external stairs straight down from the courtyard level, the ground floor was also accessible from the courtyard level, while the upper floor was accessible via external stairs, perhaps in the form of a covered vestibule.

The second building erected in the English period, probably already in the first half of the fourteenth century, was the hall located at the perimeter wall (which was slightly shifted north), between the north-west tower and the residential building. The hall, 13 meters long and 6 meters wide, served as a place for meals, feasts and inviting of guests, gathering there for official meetings and ceremonies. It was located on the upper floor, accessible via external stairs, warmed by a fireplace, equipped with a latrine on the west side and connected to the adjacent buildings. The lower, ground floor had a separate entrance, it was only for storage purposes.

The entrance to the upper castle was transformed and additionally fortified in the second half of the 13th century. The gate portal was moved further west to the longer curtain, which was completely rebuilt. On its inner side, perhaps a gatehouse was placed (this area was significantly transformed in early modern times, only the lateral loop holes and the door’s bar hole remain from the inner gate) and a four-sided turret west of it, protruding in front of the perimeter of the main defensive wall. Inside it was a small room with a latrine, located above the ground floor at the height of which chutes were pierced. Turret was adjacent to the rear of the new foregate, which ran in the form of an elongated gate neck (passage) along the southern curtain of the defensive wall and ended below the hill with an entrance portal, located before the ditch separating the upper castle from the outer ward. The entrance to the foregate was probably closed by a portcullis and a door. Defensive wall-walks flanked it along its entire length: in the south placed in the crown of the gate’s neck wall, and in the north in the wall of the upper castle.

To the east of the upper castle there was an outer ward wall, fortified with a wall and a dry moat (ditch). Its area separated into a slightly higher northern part and a lower southern part, in the eastern part of which the gatehouse was placed. The inner buildings of the outer ward are not exactly known. We only know that in 1282 two large and three small buildings of unknown purpose were erected there. It can only be assumed that they were stables, barns, sheds, etc. economic buildings needed for the daily functioning of the castle.

Current state

The castle survived to modern times in the form of a very well-preserved ruin with all the main elements from the Middle Ages. In the relatively weakest state there is only an outer bailey. The inner ward also shows the effects of the seventeenth-century rebuilding, which, by introducing large windows, changed the crowning of the keep and the façade of the northern residential building. Also the big stairs in the southern part of the ward are an early modern addition.

bibliography:

Caple C., Rees S., Dinefwr Castle, Dryslwyn Castle, Cardiff 2007.

Davis P.R., Castles of the Welsh Princes, Talybont 2011.

Davis P.R., Towers of Defiance. The Castles & Fortifications of the Princes of Wales, Talybont 2021.

Kenyon J., The medieval castles of Wales, Cardiff 2010.

Lindsay E., The castles of Wales, London 1998.

Salter M., The castles of South-West Wales, Malvern 1996.