History

The passage tomb, today called Din Dryfol, began to be built about 5,000 years ago, in an area not covered by dense Neolithic settlements. It served the local population for a common burial of the dead, at a time when the gradual transition from a gathering and hunting society to a more settled one leading an agricultural life, influenced the development of a sense of territorialism and inheritance rights. As a result, people began to pay tribute to their ancestors and the dead by building monumental tombs, near which ceremonies and worship could be performed.

On the island of Anglesey, megalithic tombs were built scatteredly, without close clusters, which most likely reflected the settlement of independent communities, perhaps divided into various tribes, each of which had one tomb on its lands. For this reason, architectural styles interpenetrated there and no single building tradition dominated. Din Dryfol itself was not a homogeneous building and typical in all its structural elements, among other things, due to the combination of stone and wood. The tomb was probably built and expanded in several, at least two phases, separated by a maximum period of about a hundred years. Despite this, unlike many other megalithic structures, cremated bodies were not interred there for a very long time.

In the Bronze Age Din Dryfol was no longer in use, although the adjacent river valley was still inhabited at that time. Intense occupation in the center of the valley continued during the first few centuries AD, with the large Romano-British population causing great damage to the Neolithic tomb, the ruins of which may have been used as a partial shelter. During the medieval period, the hamlet of Dindryfwl was the center of a thriving community, using a chapel and mill near the tomb. The population declined with the consolidation of estates in the 16th century and the final closure of the mill. The tomb may have suffered further damages during the period of increased agriculture in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Architecture

Tomb of Din Dryfol was situated on a level terrace or stone ledge, jutting out from the northern part of Dinas, a massive ridge dominating the floor of the wide and shallow valley of the River Gwna, one of several that divided the rocky plateau of the Isle of Anglesey into a series of parallel valleys and ridges. The terrace area sloped steeply to the north and west, while on the south side the cliffs rose above it in a series of high steps leading to the bare peak of the rock some 25 meters above. The only convenient approach to the terrace was from the east, while the top of the rock could be reached via a steep ramp that rose slightly southwest of the entrance to the tomb.

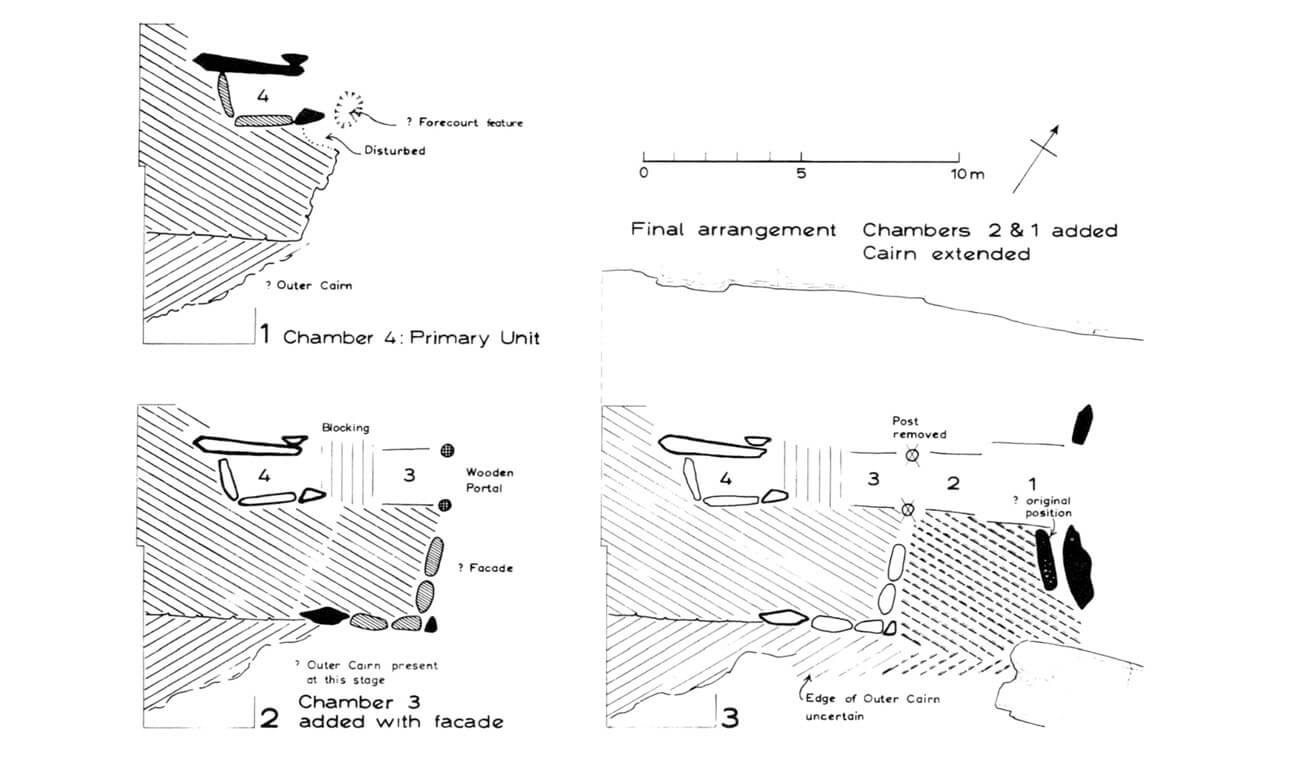

Din Dryfol was orientated with its longer sides north-east and south-west and adapted to the shape of the ledge. It was created in two or three different phases. The first, oldest chamber, located on the westernmost side, was built of side stones placed vertically with their longer axes and a capstone, creating a rectangular room measuring 3 x 1 meter. The height of the chamber was about 2 meters, and the boulder covering it was 3 meters long and 1.5 meters wide. Originally, it covered only half of the chamber, above which there must have been another similar stone.

The second burial chamber was built north-east of the first one. It was 1.2 meters wide. The length was at least 2 meters, maximum about 3.5 meters. Regardless of its length, it had a rectangular shape in plan. Perhaps its walls in some sections were not composed of large boulders placed vertically on axes, but of stones laid without the use of mortar with their longer sides horizontal. The most unusual feature of the chamber were two circular pits (0.4 meters in diameter and 0.38 meters deep), placed 1.2 meters apart at the eastern end. These holes were very carefully cut, with vertical sides and a flat base. This regularity would indicate that it were created for wooden poles, perhaps related to a structure that existed before the chamber was built. However, the arrangement of the adjacent stones would indicate that they were built together with the second chamber. They may have constituted a wooden entrance portal to the first phase tomb, functioning until the building was extended to the east. The poles were deliberately removed and their holes were filled in, not left in place in the holes where they would rot over time.

The third chamber was located north-east of the second one. Even further to the north-east, the fourth chamber was located, but it cannot be ruled out that it was one large space, less than 5 meters long. If there were two chambers, they were about 2.8 and 2 meters long. The width of the deeper space was about 1.2 meters. The outer one was slightly wider, which would also indicate a division into separate chambers. When construction was completed, the entire structure of the tomb consisted of three or four rectangular, connected chambers in the form of a long gallery, although there may have been a gap between the first and second chambers. The entrance to the tomb was probably accentuated by a kind of portal made of two tall boulders. Another characteristic element was the simple, straight facade, without a yard where cult activities would focus.

All chambers were covered with a cairn of stones, probably originally small and circular above the first chamber, but much longer and wider when all the chambers were built. Ultimately, the mound stretched for about 65 meters and was about 15 meters wide. In plan, the shape of the mound did not correspond to any standard type, but it imitated the line of rock ridges on both longer sides, which could make it narrow towards the west. For its construction, not only small stones were used, but also large boulders placed directly on the clay substrate. The larger building material formed the inner part of the mound, the smaller one the outer part. Mentioned reduction in width affected the outer part of the cairn rather than its inner core, which maintained a fairly constant width of approximately 9 meters. The large inner stones may have been associated with the first phase of the tomb’s construction, the outer part with the stage of its expansion.

Current state

The structure of the first, oldest, partially preserved burial chamber can still be seen today, but its capstone has slipped to the side and is lying on the ground. In addition, several boulders forming the walls of the chamber were lost. The second chamber has not survived, but two holes indicate where an unusual wooden portal or possibly another structure of unknown purpose stood. From the third chamber, only fragments are visible in the form of a large vertical stone, 3 meters high, and a fragment of another stone located some distance away. As you can see in the photos, the mound (cairn) has mostly degraded and dispersed.

bibliography:

Castleden R., Neolithic Britain: New Stone Age sites of England, Scotland and Wales, London 1992.

Lynch F.M., Smith C.A., Trefignath and Din Dryfol. The Excavation of Two Megalithic Tombs in Anglesey, Cardiff 1987.

The Royal Commission on The Ancient and Historical Monuments and Constructions in Wales and Monmouthshire. An Inventory of the Ancient Monuments in Anglesey, London 1937.