History

Criccieth Castle was built around 1230 by Llywelyn ap Iorwerth (Llywelyn the Great), Welsh prince of Gwynedd. The stronghold certainly existed already in 1239, because then Gruffydd ap Llywelyn, son of Llywelyn ap Iorwerth, was imprisoned there by his half-brother, Dafydd. For the second time, the castle was mentioned in 1259, when Llywelyn ap Gruffydd for a few months imprisoned Maredudd ap Rhys from the Deheubarth, as punishment for conspiring against him. Furthermore, Criccieth, without reference to the castle itself, was recorded in an ode by Einion ap Madog, in which Gruffydd ap Llywelyn was referred to as lord of Criccieth (“Pendefic Crukyeith”).

The death of a strong native ruler Llywelyn ap Iorwerth in 1240, caused king Henry III of England tried to strengthen his supreme power over Wales, and under the Woodstock Treaty of 1247, he deprived Gwynedd of control over all the lands east of Conwy. In the next decade, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd took up the fight to restore Gwynedd’s domination, wrestling with the English ally, Maredudd ap Rhys Gryg, who was captured and imprisoned in Criccieth Castle. In the end, Gruffudd won, and by virtue of the Treaty of Montgomery from 1267, he was accepted by the English and Welsh. However, this achievement was relatively short-lived, because the Welsh prince entered into conflict with the new king of England, Edward I, starting in 1276 the First War of Independence. During this time, the Criccieth Castle, lying on the sidelines, did not play a significant role.

When the Second Welsh Independence War began in 1282, the English king decided to conquer all of Wales. Criccieth was captured in 1283. There was no record of fighs or a siege, except that Henry of Greenford was paid to garrison “Cruketh” with an English garrison of thirty men at the time, and in 1284 William Leyburn was appointed the new constable of the castle. After the Welsh defeat, Edward I issued significant funds to build a chain of strongholds protecting the conquered areas of North Wales. It also included renovations and modernizations of some former Welsh castles. In the years 1285-1292, 353 pounds were spent on Criccieth, a sum sufficient for extensive construction works, although incomparable to castles built from the foundations.

In 1294, Madoc ap Llywelyn began an anti-English uprising that quickly spread to most of Wales. Criccieth Castle, garrisoned by 29 armed men under the command of William Leyburn (and 41 fugitives) was one of many attacked in 1294. However, the fortification of the “castrum Crukyn” and its location by the sea made it possible to supply from the Bristol ships and, as a consequence, keep for a few months until the arrival of reinforcements and suppress rebellion (6000 herrings, 550 large salted fish, 30 wheat quarters, 27 quarters of beans, 20 pounds of twine for crossbows, 50 stockings and 45 pairs of shoes, as well as 24 salted pigs and 18 cheeses were delivered). No damage to the castle was recorded, but considerable sums were spent on its repairs and maintenance in the fourteenth century, during the reigns of Edward II and Edward III. It must have been considered a strong and secure stronghold, for prisoners captured in the wars with Scotland were held there until the reign of Richard II.

In 1343, King Edward III granted the castle to his son Edward the Black, Prince of Wales. Around 1360, after a series of English constables, he appointed a native constable of the castle, the first Welshman since the castle had been capture by the English. Hywel y Fwyall received this honour in return for his services at the Battle of Poitiers in 1356, on the fields of which he was knighted. He held this new office until his death in 1381. During the time of Hywel, his predecessors and successors, numerous repairs were carried out on the castle, mainly concerning lead roof coverings, doors, windows and stonework in the walls. In 1352, the residents of the commote Eifionydd, in which the castle was situated, paid fees “pro opere manerii castri de Cruckith”, and in 1386 and 1402 minor repairs were financed.

During the next Welsh revolt of Owain Glyndŵr, caused by excessive taxation and hard English rule, in 1400 almost all of north-west Wales was taken over by rebels, with the exception of isolated strongholds in Criccieth, Aberystwyth and Harlech. Criccieth as late as 1402 was garrisoned only by one man-at-arms and twelve archers, but was soon garrisoned by six men-at-arms and fifty archers under the command of Roger Acton. But this time, thanks to the French support at sea for the Welsh people, supplies and meals could not be delivered to the castle. As a result, in 1404, the English garrison surrendered, and the Welsh destroyed the castle. From that moment it was said to have been in ruins, although a document from the mid-15th century would indicate that Criccieth was still garrisoned at that time. It is likely that the fire and complete abandonment of the castle, and the subsequent decline of the nearby settlement, occurred shortly afterwards.

Architecture

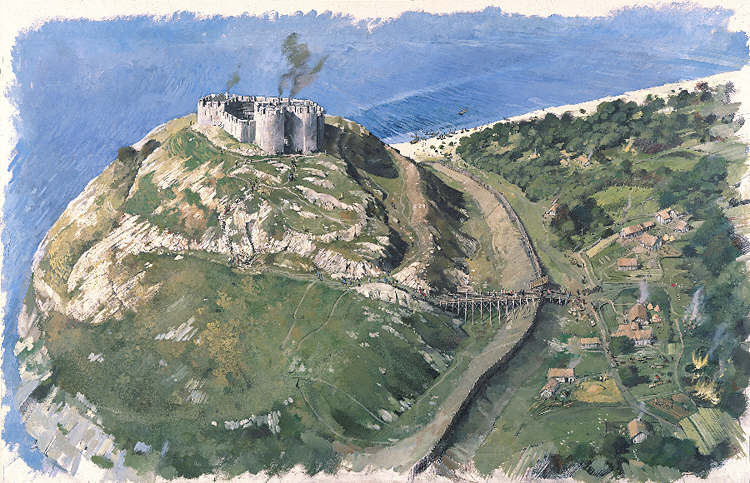

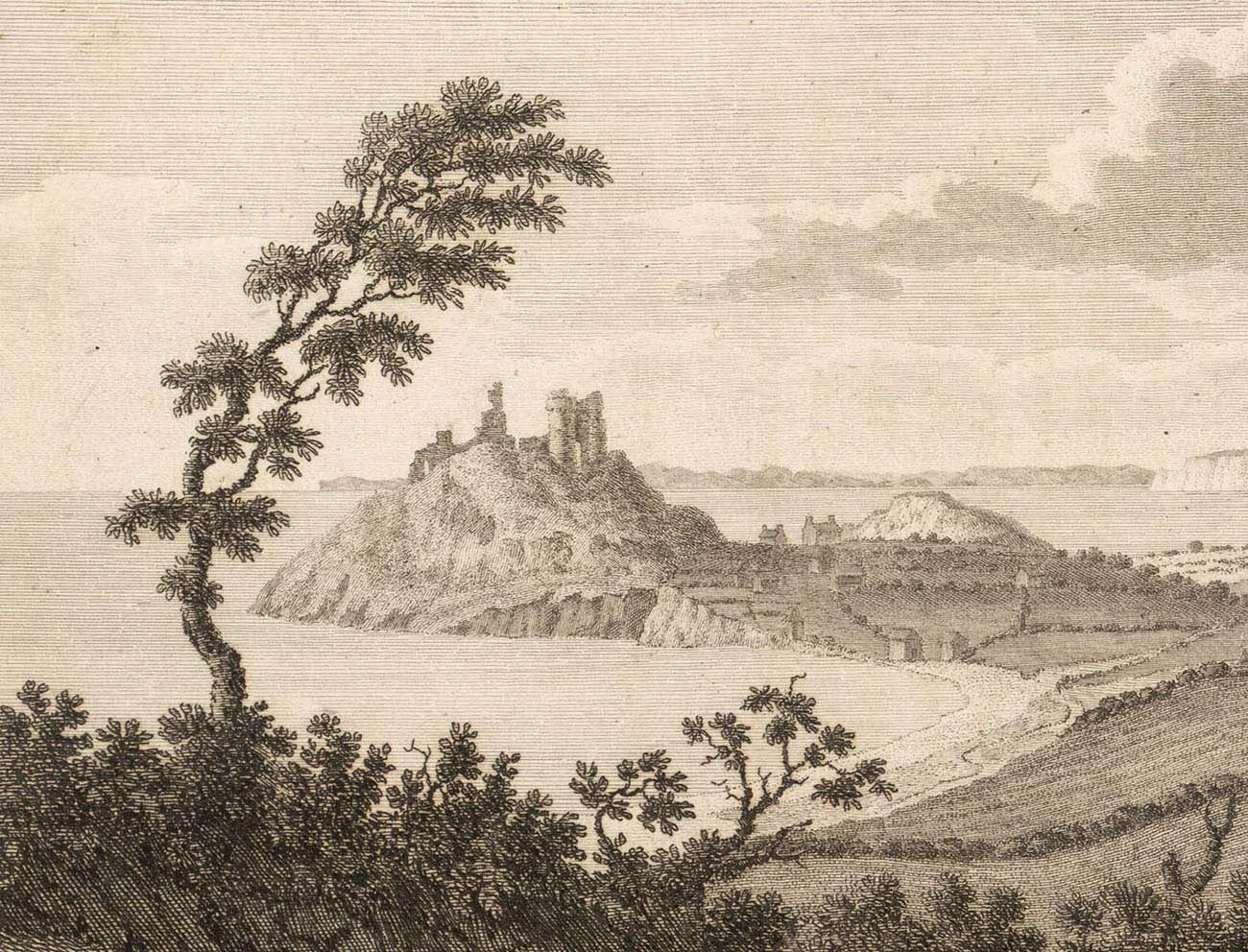

Criccieth Castle was situated on a high, rocky promontory, jutting south towards the waters of Cardigan Bay. Steep and inaccessible cliffs provided protection especially on the south and east sides, where it fell directly into the water, but the western slopes were also characterized by large drops. The only relatively convenient access road could lead from the north, along rather narrow paths created among the rocky slopes. There, at the base of the hill, the approach to the castle was protected with earth fortifications, stretching across the neck from the south-west cliff to the north-east cliff. It consisted of a wide ditch and an earth rampart preceding it, perhaps topped with wooden fortifications in the form of a palisade.

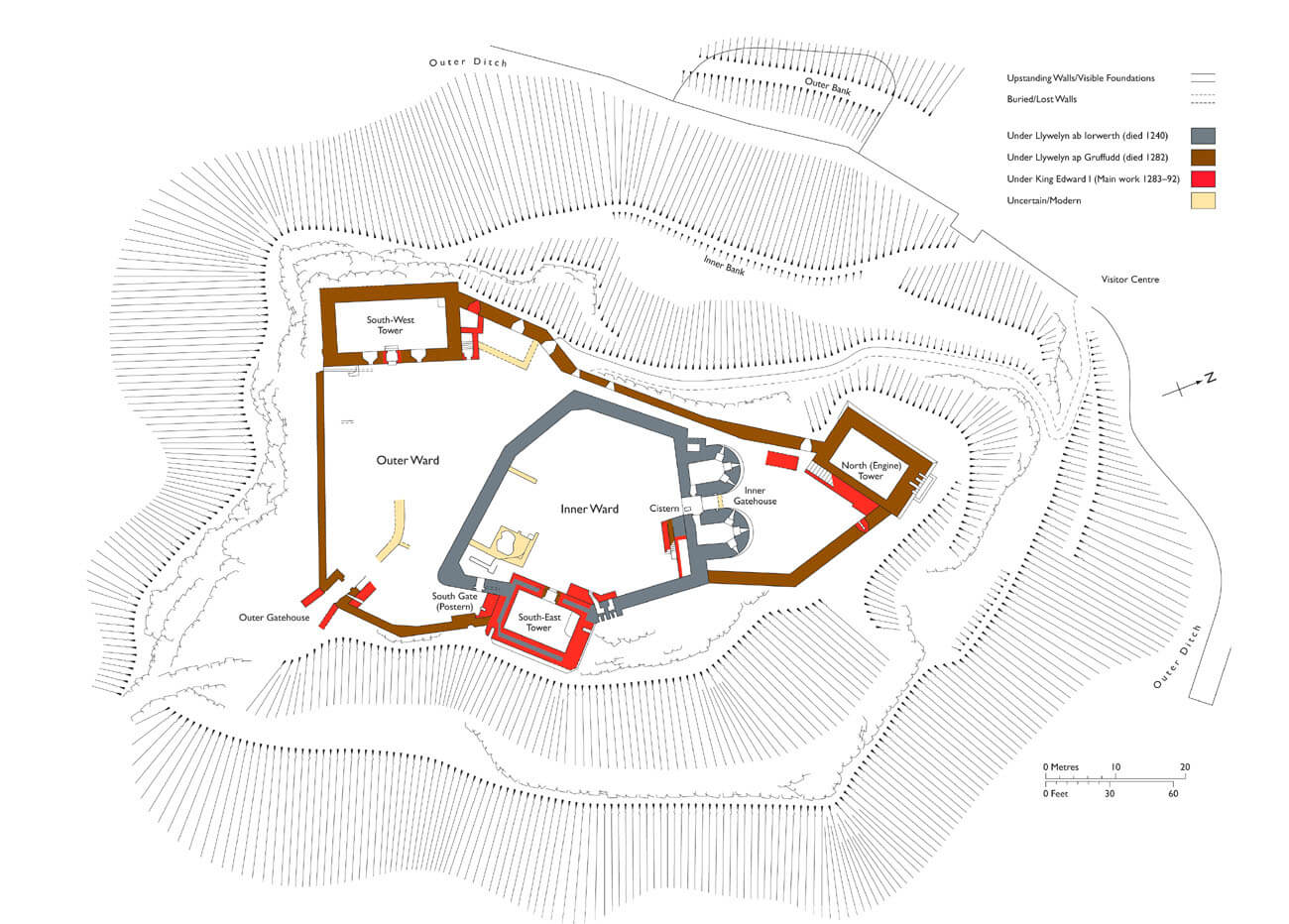

The oldest, Welsh part of the castle, built by Llywelyn ap Iorwerth, was the later central part of the complex, situated at the highest point of the terrain. It consisted of a hexagonal defensive wall, enclosing a courtyard measuring 30 x 27 metres. This part was built of angular, unworked local stone, supplemented with larger boulders brought from the beaches at the base of the hill. The walls reached a height of about 5.3 metres to the level of the wall-walk, which was exceeded by the 2.1 metres parapet. The thickness of the walls reached about 1.8 metres at the ground level. The residential buildings originally consisted of a rectangular tower house protruding from the defensive wall on the south-east side and a smaller wooden or half-timbered building attached to the perimeter wall on the south. The south-east tower house on the south side protected a small postern, initially leading to the seaside escarpments and later to the outer bailey. The main entrance to the castle was from the north, through a fortified gate inspired by Anglo-Norman architecture. The entire plan of the core of Criccieth Castle resembled Montgomery Castle, built at the same time and known to Llywelyn from two sieges he led.

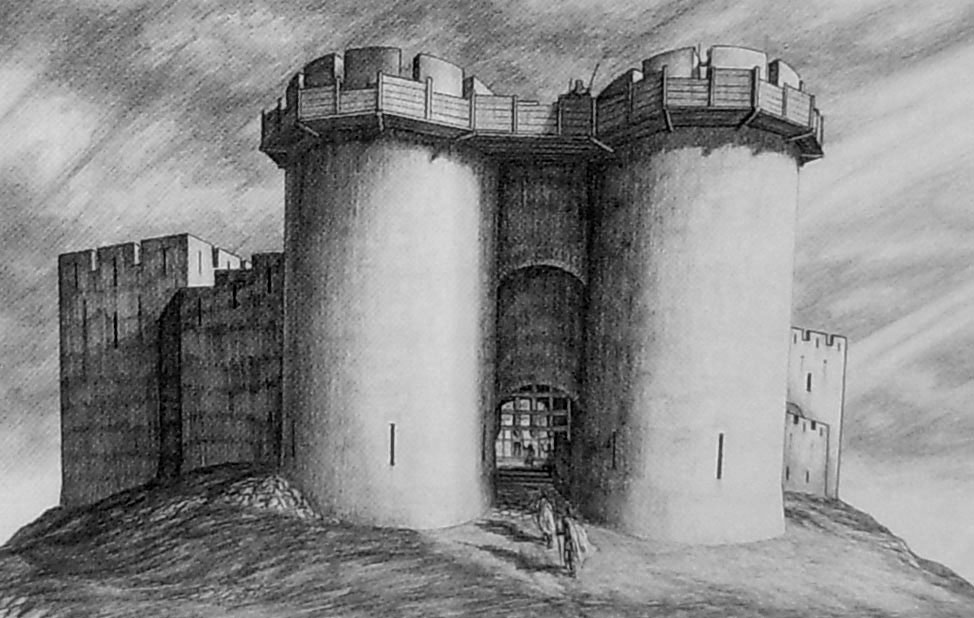

The gate consisted of two massive horseshoe-shaped towers, flanking the passage between them. The passage was protected by a portcullis, double doors and numerous arrowslits, including those placed in the ceiling of the gate passage (so-called murder holes). Unusually, at the exit of the passage there was a rectangular water tank, supplied by a small spring, walled with stone and closed with a wooden cover. In the ground floor of the gate towers there were single rooms, each with three radially arranged arrowslits set in segmental and splayed recesses. The two upper floors, separated by wooden ceilings, contained large rooms occupying both towers and a space between them. The latter contained a mechanism for raising and lowering the portcullis, while on the western side, in a small projection, latrines serving the floors were located. Interestingly, unlike the ground floor, the floors on the outside did not have any windows or arrowslits. This was probably compensated by a wooden hoarding, suspended at the wall of the upper floor. The lighting of the rooms on the floors must have been provided by windows on the inner, southern side (facing the courtyard), which is probably where the fireplaces heating the rooms were located. The entrance to the first floor was provided by stairs located in the courtyard. The crown of the wall was secured by a battlemented parapet, in the merlons of which there were arrowslits. These merlons were 0.9 meters high, 0.4-0.5 meters thick, and about 0.8 meters below them on each of the gate towers there was a row of holes, most probably used for mounting a wooden hoarding mentioned above.

In the 60s or 70s of the 13th century, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd added to the castle a southern ward, fortified with a stone wall and a rectangular tower in its corner, located on the south-west side. The southern ward was connected by a curtain with the newly created northern ward, with only a very narrow passage left between the two at the base of the upper ward wall. The outer wall that formed this passage was equipped with six arrowslits embedded in deep niches, directed towards the borough outside the castle. The narrow passage was originally covered with roof (as evidenced by the openings for beams in the wall of the upper ward) and from then on was an access road to the upper castle, because the outer gate was set on the southern ward, in a small four-sided gatehouse, entirely placed inside the perimeter. In order to reach the very top, it was necessary to circle the entire complex under the watchful eye of defenders patrolling the wall-walks of the upper ward. It is not known whether the latrine in the gate tower could still function after the building of a narrow passage between the courtyards, the outlet of which was directed towards this only connection.

During the English rebuilding of Edward I, the main castle gate was raised using smaller-sized stone. The builders’ aim was probably to re-establish control of the access road to the castle, above the buildings of the northern ward, which obscured the approach for defenders from the core of the castle. In connection with the heightening of the gate and the desire to improve communication between the courtyard, the curtain walls and gate complex, and as a result the desire to achieve more effective passive defence, a stone staircase was added to one of its gate towers from the courtyard side. It were also connected to the wall-walk in the crown of the nearby wall. The south-eastern tower of the upper ward and the south-western tower of the outer ward were also rebuilt and raised. Both quadrangular towers were probably raised by third storeys. In addition, a foregate to the gatehouse was added on the southern ward, situated entirely in front of the defensive perimeter, with a slightly widening passage in the frontal part.

The rectangular southeastern tower house on the upper ward was thoroughly rebuilt in the 1280s. Its perimeter walls were reinforced from the outside and inside, and it were slightly extended from the north and south, thanks to which the structure reached dimensions of about 14 x 10 meters. Initially, the entrance probably led up wooden stairs from the courtyard to the first floor, and from there by stairs or a ladder to the ground floor. During the reconstruction, a new entrance was inserted at ground level in the middle of the western wall and equipped with double-leaf doors, set at the beginning and end of the corridor pierced through the thickness of the wall, one of which could be blocked with a bar set in an opening in the wall. In addition, the wooden stairs leading to the first floor were rebuilt using stone, although still in the Middle Ages this was considered a mistake and it were removed for defensive reasons. It is known that the first floor was heated by a fireplace and serviced by latrines set in the southern corner and just behind the tower, by the curtain wall on the northern side. Such a large number of latrines would indicate that the building had another third residential floor since the reconstruction, although the two pairs of northern latrines could also have been used by guards on duty on the walls.

The south-west tower, measuring 20 x 11.5 metres, probably initially had only two floors and was similar to the tower of Dolwyddelan Castle built by the Welsh. The first floor must have originally been accessible by means of a ladder or wooden stairs from the ground floor. It was not until English times that an entrance was made on the ground floor, flanked by two arrowslits set in deep recesses in the eastern wall. In addition, stone stairs leading to the first floor were also built on the north side, in the angle created by the curtain wall. The hygiene of the inhabitants of the tower upper floor was probably ensured by a latrine, placed in the thickness of the wall of the south-eastern corner.

The defence of the northern ward was ensured by a quadrangular tower placed in the protruding corner. This tower, called the “Engine Tower”, may have been built already in the times of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, but it was raised and rebuilt during the reign of Edward I. It probably served as a base for medieval siege machines, which, thanks to its protrusion in front of the castle, had a good field of fire. Its three outer elevations were reinforced with a sloping batter, with two pairs of latrine chutes located in the eastern one, serving the first floor and the topmost combat floor. Inside, the ground floor of the tower was unlit and accessible only by a ladder from the first floor level. It probably served as a warehouse. The first floor was accessed from the time of Edward I by an external stone staircase from the courtyard. Its gentle slope would indicate that heavy war materials were brought up to the first floor.

Current state

The castle has been preserved in the form of a ruin with a clear layout of all defensive elements, although the medieval road leading to it (to the outer gate) has fall to the bay and now the monument is circled from the west and not from the east. Its main and at the same time the best preserved part is the main gatehouse of the upper ward, consisting of two huge flanking towers. The defensive wall surrounding the inner ward also survived in good condition, only the ground parts and foundations have survived from the remaining fragments. The ruins are open to visitors.

bibliography:

Avent R., Criccieth Castle, Cardiff 1989.

Davis P.R., Castles of the Welsh Princes, Talybont 2011.

Davis P.R., Towers of Defiance. The Castles & Fortifications of the Princes of Wales, Talybont 2021.

Kenyon J., The medieval castles of Wales, Cardiff 2010.

Lindsay E., The castles of Wales, London 1998.

O’Neil B.H., Criccieth Castle, Caernarvonshire, „Archaeologia Cambrensis”, 98/1944.

Salter M., The castles of North Wales, Malvern 1997.

Taylor A. J., The Welsh castles of Edward I, London 1986.

The Royal Commission on The Ancient and Historical Monuments and Constructions in Wales and Monmouthshire. An Inventory of the Ancient and Historical Monuments in Caernarvonshire, volume II: central, the Cantref of Arfon and the Commote of Eifionydd, London 1960.