History

Before the English conquest, the area of town of Conwy was occupied by Aberconwy Abbey, a Cistercian monastery supported by Welsh princes and burial place of representatives of the Welsh dynasty from Gwynedd. Aberconwy also controlled an important crossing over the Conwy River, between the coastal and inland areas of North Wales. English king Edward I captured Aberconwy in 1283 and decided that this place would become a strong, fortified center of the new county, and the abbey will be moved inland (the monastery church became the Conwy parish church). Edward’s plan was also symbolic, an act showing the English power.

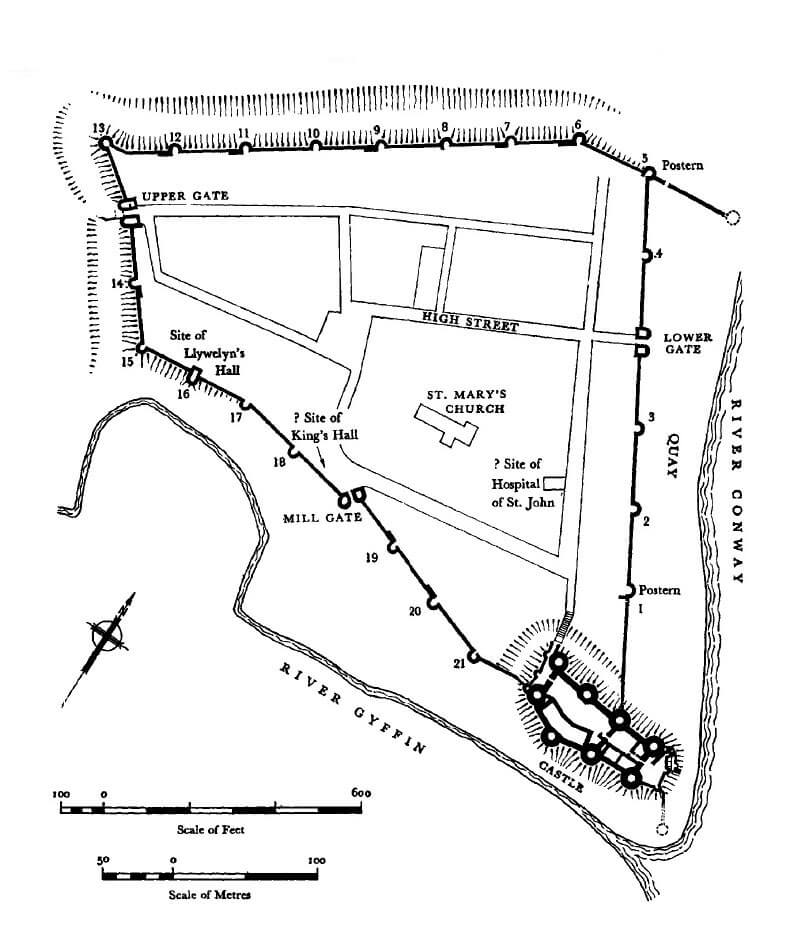

The construction of the town walls began in 1283 under the general supervision of master James of Saint George, the chief architect of Edward in North Wales. Every year, a large number of workers from all over England were mobilized, gathered in Chester, and then transported to Wales for the construction season. The first stage of work on the walls included digging ditches, erecting a palisade around the future town to secure the area to allow further works and the construction of a half-timbered mill on the Gyffin River. In the years 1284-1285, Richard, deputy of master James, built the north and west side of the circuit. It was the most vulnerable direction and was deliberately chosen as a priority. In 1286, John Francis, a Savoy mason master, completed the southern side of the circuit, and in 1287 the remaining section of the walls along the east quay was completed under the supervision of Philip of Darley. The total cost of the town walls together with the castle amounted to a huge sum of about 15,000 pounds.

The newly created fortifications were to provide security to English colonists from nearby Cheshire and Lancashire counties. Although the constable of the Conwy castle was also the mayor of the town, the care of the walls was probably the responsibility of the residents, not the garrison of the castle. At the beginning of the 14th century, the stands for crossbowmen were modernized on the walls to further increase their defenses.

In 1400, the Welsh leader Owain Glyndŵr caused an uprising against English rule. Two Owain cousins took control of the castle in 1401, and then, despite the fortifications, also the town. Conwy was occupied for two months and was plundered by Welsh rebels. Residents complained later that there was damage of £ 5,000, including damages to town gates and bridges.

Even in the 20s and 30s of the 16th century, town fortifications were repaired on the initiative of Henry VIII. However, ascension to the throne of the Tudor dynasty, who were of Welsh descent and softened the tensions between the Welshmen and the English, began to change the way Wales was managed and reduce the military importance of the town’s defensive walls. Part of the fortifications began to be robbed of stones, some began to be covered by residential houses, and the moat began to be used for storing garbages. Unfortunately, in the nineteenth century, further changes were made in the town walls, so that a new railway line and road could be installed nearby. In 1826, two new gates were opened to facilitate street traffic. The interest in town fortifications increased at the end of the 19th century. Restoration was started and part of the walls for tourists was made available.

Architecture

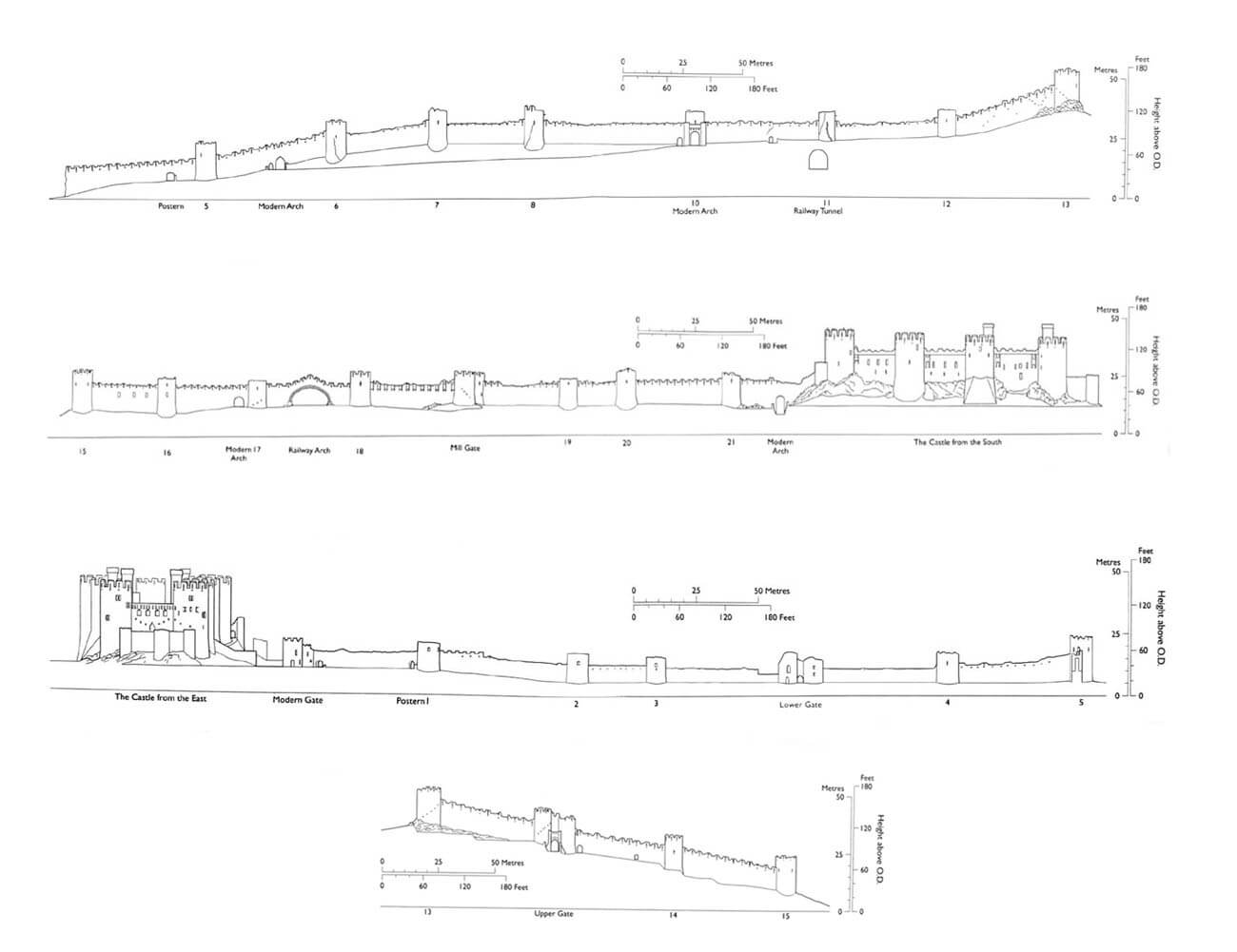

The town walls in Conwy were built on a plan similar to a pentagon with the western part clearly shorter and south slightly broken. In addition, in the northern corner, a short fragment with a length of 55 meters was built out of the perimeter towards the waterfront, protecting access to the port area of Conwy. The total length of the fortifications was about 1,300 meters and closed the area of almost 10 hectares. Most of the town and its fortifications were built on flat terrain, except for the west corner situated on a slight hill. In the south-eastern corner of the perimeter, the town walls were connected with the fortifications of the castle, located on a rocky headland at the mouth of the Gyffin River to the wider Conwy riverbed.

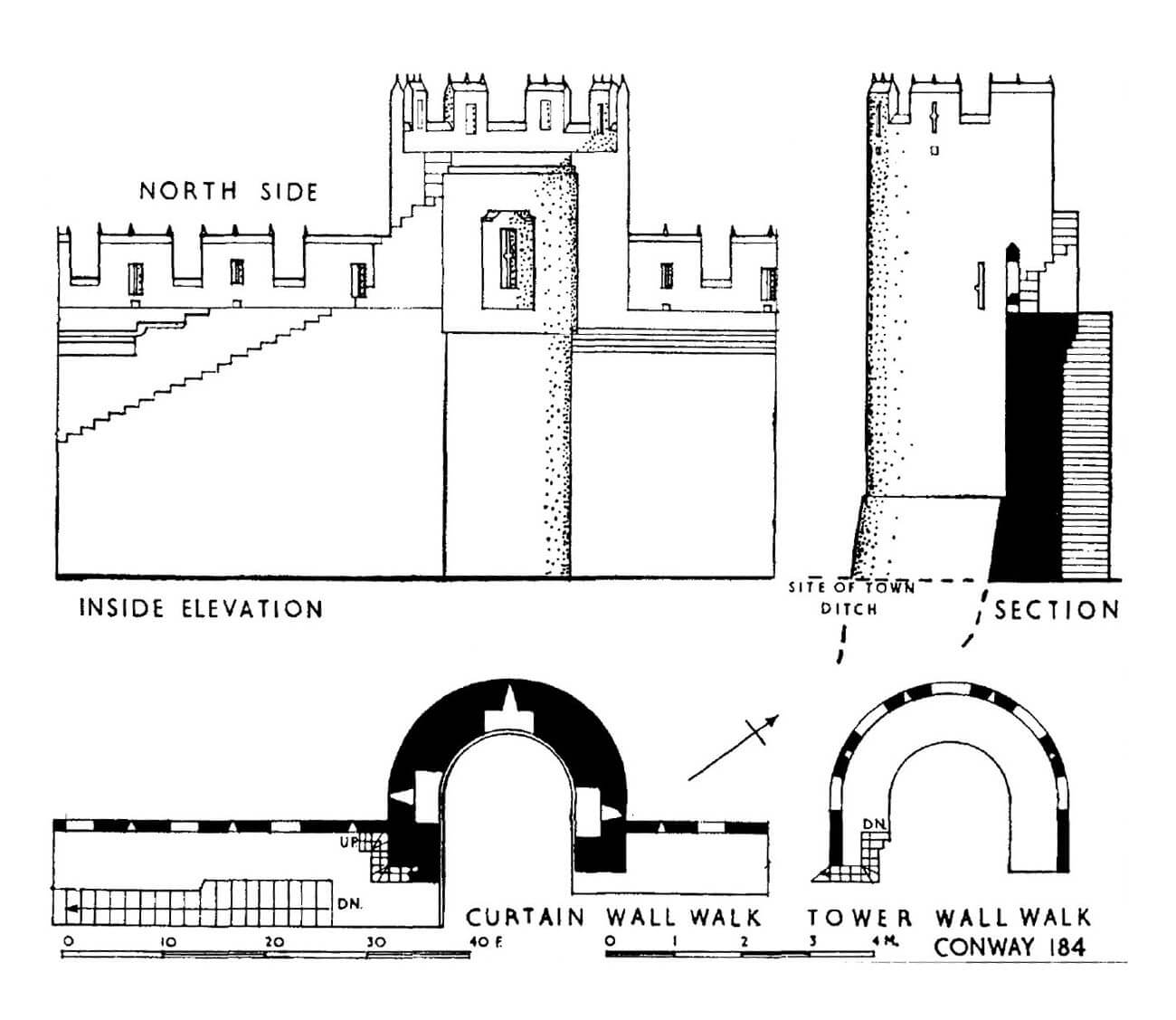

Walls were erected from local sandstone and limestone with the additional use of ryolite in the upper parts. Its thickness was 1.7 meters, and the height was 9 meters (5.2 meters to the level of the wall-walk from the town side), although from the eastern, coastal side, the height of the wall was originally only 3.6 meters. It was raised there of a pale rhyolite only in the 14th century. Lower, thinner (only 91 cm thick) and devoid of wall-walk for defenders were also short fragments of the wall near the castle on the section near the ditch. Whereas the wall protecting the waterfront on the north-eastern side was more than twice as thick, over 3.1 meters wide, probably due to water washing.

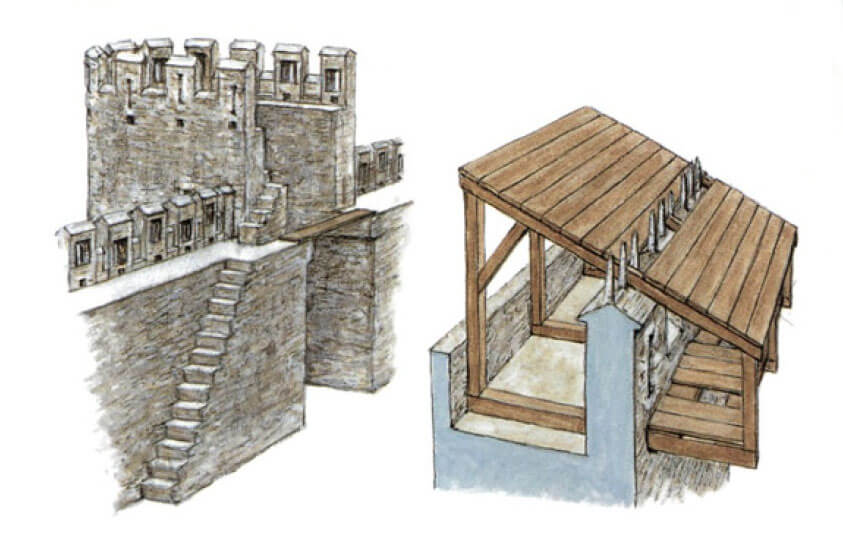

The wall on most of the circuit was crowned with a battlement with arrowslits in merlons and a stone, wide wall-walk for defenders. Merlons (crenels), 2.1 meters wide, were spaced at 0.9 meter intervals. At first, the arrowslits were straight vertical slits, but in the fourteenth century received additional horizontal slits reaching the shape of crosses with better visibility. What’s more, the merlon’s arrowslits were pierced alternately at different heights to allow shooting at the far and near foreground. Each of the merlons had an unusual triple small stone pillars, similar to the one used at the castle. Perhaps the upper part of the walls was also crowned with hoarding, or at least their construction was planned judging by the preserved holes in the wall. The fragment of the southern wall between the 18th tower and the Mill Gate had an interesting system of twelve, evenly and densely arranged protrusions from the outside. Originally, they served as a latrine rather than a defensive one. The entrance to the crown of the walls was made possible by stone stairs attached to them from the inside, located near almost every tower and gate.

The defensive wall was reinforced by 21 towers, evenly spaced at approximately 45 meter intervals, most of them semicircular with a diameter from 4 to 5.2 meters, open from the town side and roofless. The exception was the western, cylindrical corner tower, and the south-western, a closed horseshoe-shaped tower (tower No. 16) located near Llywelyn’s Hall. The twenty-second cylindrical tower was yet at the end of the wall running towards the waterfront. The height of the towers reached 15 meters, so they were higher than the defensive walls, it also protruded from their face of the walls to enable flank defense. Their interiors originally had removable timber bridges to enable the wall fragments to be cut off from the attackers. They were crowned like the town walls, battlements with arrowslits in merlons. In addition to this top combat storey, also at the level of the wall-walk of the curtains, the towers had access to three arrowslits embedded in four-sided recesses, arranged in such a way that one was on the axis and two on the sides.

The aforementioned Llywelyn’s Hall was was a timber house about 26 meters long, used by the Welsh ruler Llywelyn ap Iorwerth before the construction of English fortifications, which were added to it. For this reason, their elevations on this fragment were pierced with three windows, the only ones around the entire perimeter of the fortifications. Therefore, tower No. 16 was a closed, three-storey building, housing residential chambers inside. The most comfortable of them was a four-sided room on the first floor, equipped with a fireplace and lit by two windows. The entrance to it led through the roofed stairs from the town side and then through the portal in the north wall. Its level corresponded to the ground floor of the Llywelyn’s Hall, which in 1316 was demolished by the king’s order and moved to Caernarfon Castle.

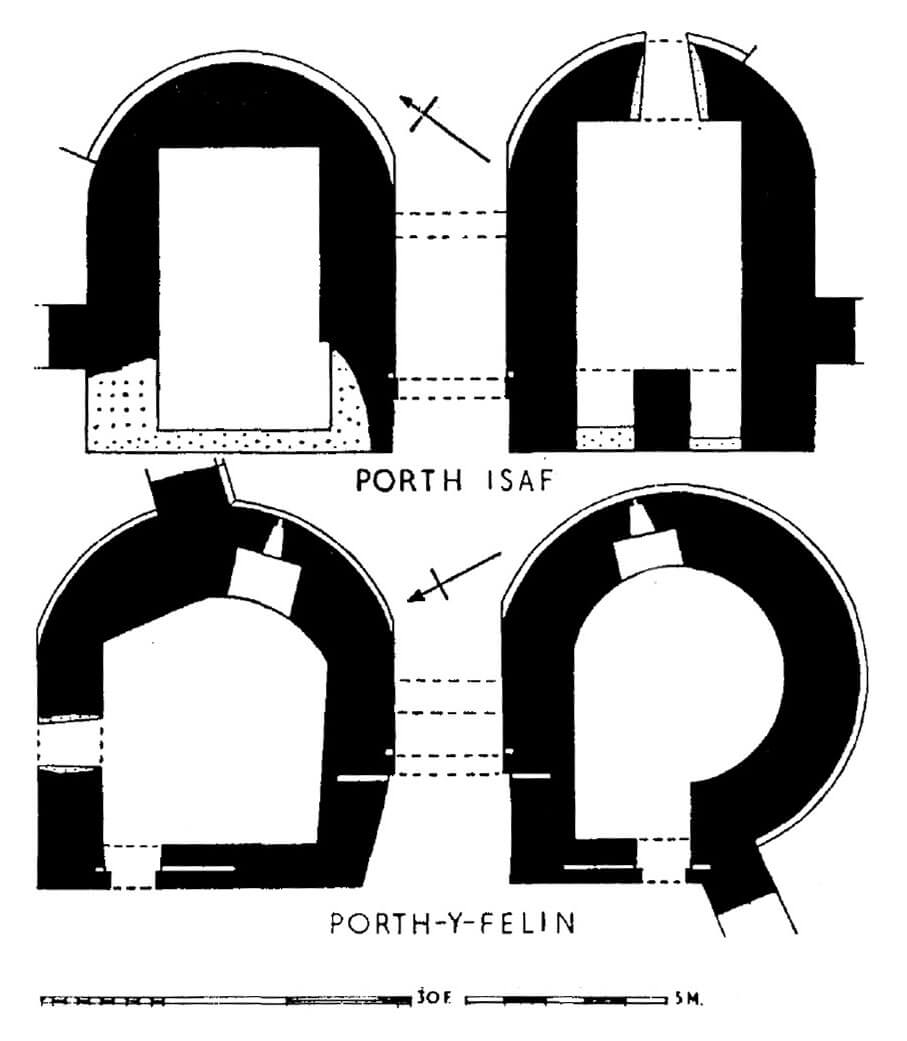

The entrance to the town was made possible by three gates: the southern one called Mill Gate, leading to the royal water mill located on the outskirts of the town, the western one called Upper and eastern Lower Gate, overlooking the seafront. On the eastern side of the perimeter, there was also a smaller wicket (postern) gate near the castle. A second postern gate functioned in the wall protecting the waterfront. It was closed with a portcullis operating as a counterweight lowered in a quadrilateral shaft. All three main gates consisted of two horseshoe towers flanking the 2.9 meters wide passage with a portcullis between them. Only the western tower of the Mill Gate was erected as cylindrical because of placing the passage in a wall bend. This gate also as the only one had chambers inside the upper, half-timbered floors warmed by fireplaces.

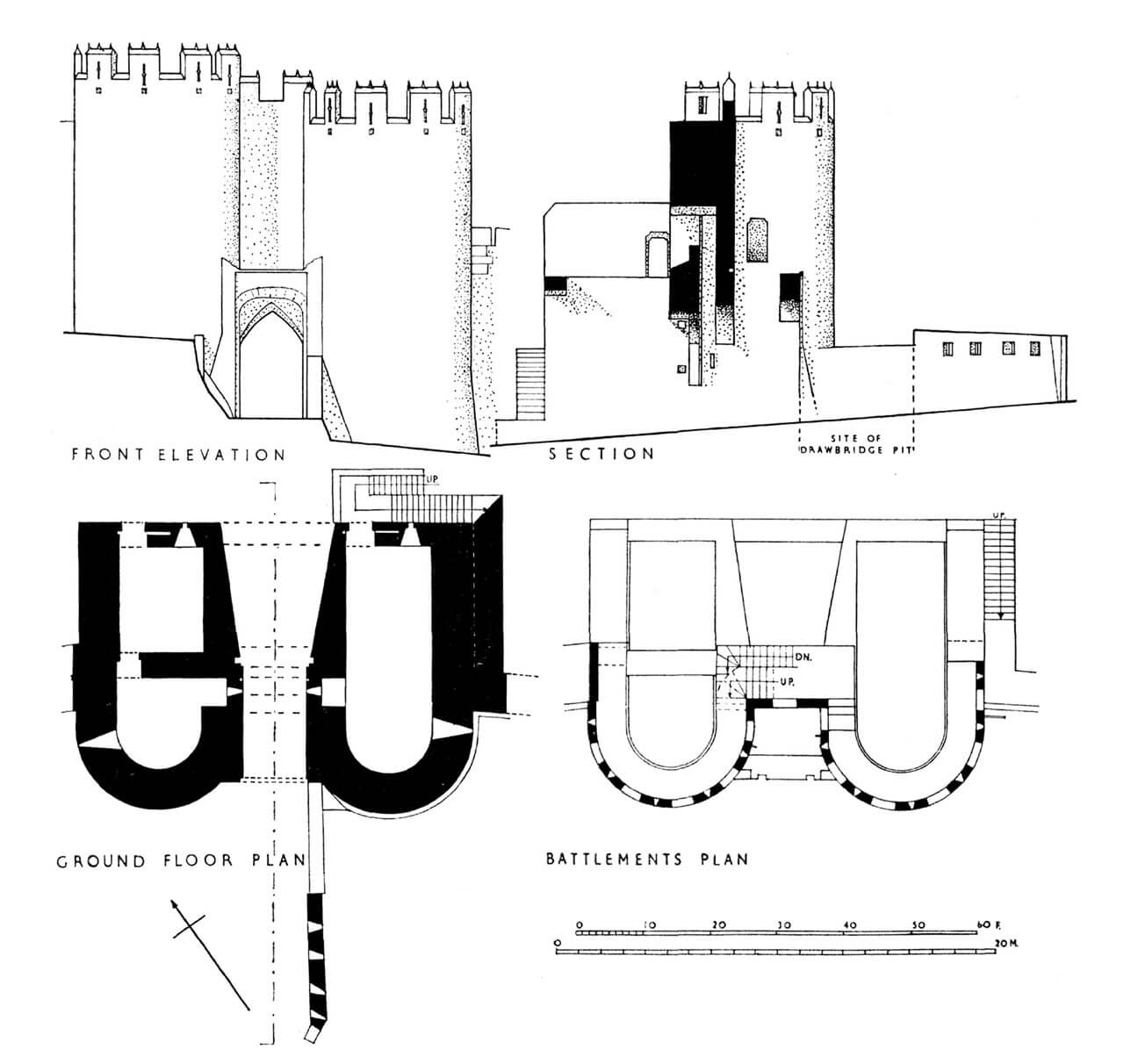

The Upper Gate, as the main entrance to the town during the Middle Ages, was the only one with a small foregate. In addition, it was protected by a drawbridge, a portcullis and timber gates closed with bars placed in the wall openings. The rooms in the ground floor of its gate towers were accessible from the town side, through doors blocked with bars. In the front part, they were pierced with arrowslits, one of which faced the gate passage, and the other flanked the adjacent curtains. Upper storeys from the town side were partly of half-timbered construction, but had a roof protecting the central room from the weather with a mechanism of the portcullis (after lifting it was blocked with two wooden beams placed in holes in the wall).

The outer defense zone was a ditch, at the Upper Gate just over 5 meters wide, probably extended only from the west and north-west, that is on a directions not protected by water barriers. In the south-eastern corner, the town walls were in contact with the castle, creating a collective defense system. From the south, access to the town was protected by the river Gyffin, flowing into the Conway near the castle, which protected the town from the east.

Current state

Today, the defensive walls in Conwy are one of the best-preserved, not rebuilt in later periods, medieval town fortifications, visible at the length of almost the entire perimeter, including gates and 21 towers. In 1986, they were added to the UNESCO World Heritage List and were classified as a Class I monument. Large fragments are open to visitors with the possibility of walking along the defensive wall-walk. The route runs from tower No. 5 in the north-east corner to the corner tower No. 13, then you can go to Tower No. 17, where a railway passage was pierced in the wall in the 19th century. The next stretch leads from the Mill Gate to tower No. 21. The largest transformations affected the eastern part of the perimeter near the castle, where in the nineteenth century a fragment of the wall was first demolished, and later rebuilt with a modern tower. A modern passage preceded by contemporary turrets was also placed in tower No. 10.

show northern part of the fortifications on map

show western part of the fortifications on map

bibliography:

Ashbee J., Conwy Castle and Town Walls, Cardiff 2015.

Haslam R., Orbach J., Voelcker A., The buildings of Wales, Gwynedd, London 2009.

Kenyon J., The medieval castles of Wales, Cardiff 2010.

Salter M., Medieval walled towns, Malvern 2013.

Taylor A. J., Conwy Castle and Town Walls, Cardiff 2003.

The Royal Commission on The Ancient and Historical Monuments and Constructions in Wales and Monmouthshire. An Inventory of the Ancient and Historical Monuments in Caernarvonshire, volume I: east, the Cantref of Arllechwedd and the Commote of Creuddyn, London 1956.