History

The castle was erected by the knight Payn de Turberville at the end of the 11th or the beginning of the 12th century during the penetration of south-eastern Wales by the Norman conquerors. Payn de Turberville was one of the twelve knights accompanying Earl of Gloucester, Robert Fitzhamon in his conquest of Welsh Glamorgan. According to a later tradition, as he did not receive any territory from his senior in the lands seized by the Welsh, around 1092 he was to take action and conquer the lands around Coity. In the face of the attack, the then Welsh ruler, Morgan ap Meurig, not feeling strong enough to fight, was to offer to return his daughter to Norman. According to unconfirmed record, Payn accepted the offer, becoming Lord of Coity thanks to his marriage. The castle itself, however, was not recorded in documents for a long time. It was first mentioned in 1207 and 1214 (castellum suum de Coitif).

Around 1180, the castle was rebuilt by another heir of Coity, one of Payn’s sons, Gilbert de Turberville, who most probably funded a keep and a ring of stone walls. Presumably, the motivation for these actions was the Welsh-Norman unrest and the rebellion of Morgan ap Caradog in 1183. Over the next years, during which the Turberville family remained the owners of Coity, the castle underwent further modernization and expansion, although, surprisingly, no major works were recorded in the 13th century. Gilbert’s successor, Payn II, was involved in the suppression of the Welsh rebellion after the death of Earl William, and then got into a dispute with a certain Walter de Sully in 1199. Another family member, Gilbert II, married Morgan Gam, daughter of the Welsh Lord of Afan, thus obtaining the Gower lordship, and in 1217 acquired Newcastle Castle. In an unknown year, Gilbert was succeeded by his son, Gilbert III. Gilbert father or Gilbert son was at war with Hywel ap Maredudd of Meisgyn in 1242, but it was certainly the younger Gilbert who received the Coity in 1262. Gilbert III was dead in 1281, and his son Richard I died two years later. A descendant of the latter, Payn III, contributed to the Welsh rebellion of Llywelyn Bren in 1316 with his provocative behavior. After fall of the revolt, in 1319 the heir of Coity was Gilbert IV, who began the further construction works in the castle, continued in the time of his son Richard, who inherited Coity in the 50s of the 14th century.

The Turbervill male’s line ended in 1384 when Richard II died, as a result of which the lordship and the castle passed to Sir Lawrence Berkerolles. He made further modernization, thanks to which the stronghold resisted sieges during the Welsh rebellion of Owain Glyndŵr in 1404 and 1405. Despite the repel of the attackers, the castle was seriously damaged and remained in poor condition until Lawrence’s death in 1411. Ownership of the property then became the object of a dispute between the Margaret de Turberville daughter, Joan Verney and William Gamage, who gathered forces and besieged Joan for a month at Coity Castle. King Henry IV ordered the removal of the siege and imprisoned William in the Tower of London. He was released in 1413 after the death of the king, and finally the castle passed into the hands of him (until his death in 1419) and his family, who made repairs and reconstruction of the destroyed stronghold (among others, a great barn was built in the outer ward). Although the Gamage family still owned Newcastle Castle, the “Coytiff Castrum” was their main residence at the time.

In the first half of the 16th century, Coity Castle was still well kept, even though the last Gamage heir, John, only dealt with the modernization of Newcastle Castle. In Coity, in the early Tudor period, some windows were replaced, new fireplaces and service stairs were installed, and a room with ovens was created, so the focus was mainly on the furnishings of the castle and the comfort of its inhabitants. In 1584, Coity passed into the hands of the Sydney family when Barbara Gamage married Sir Robert Sydney, Earl of Leicester. The new owners preferred to live on their property in England, which made Coity decayed and eventually abandoned in the first quarter of the 18th century. The castle turned into a ruin till the 19th century.

Architecture

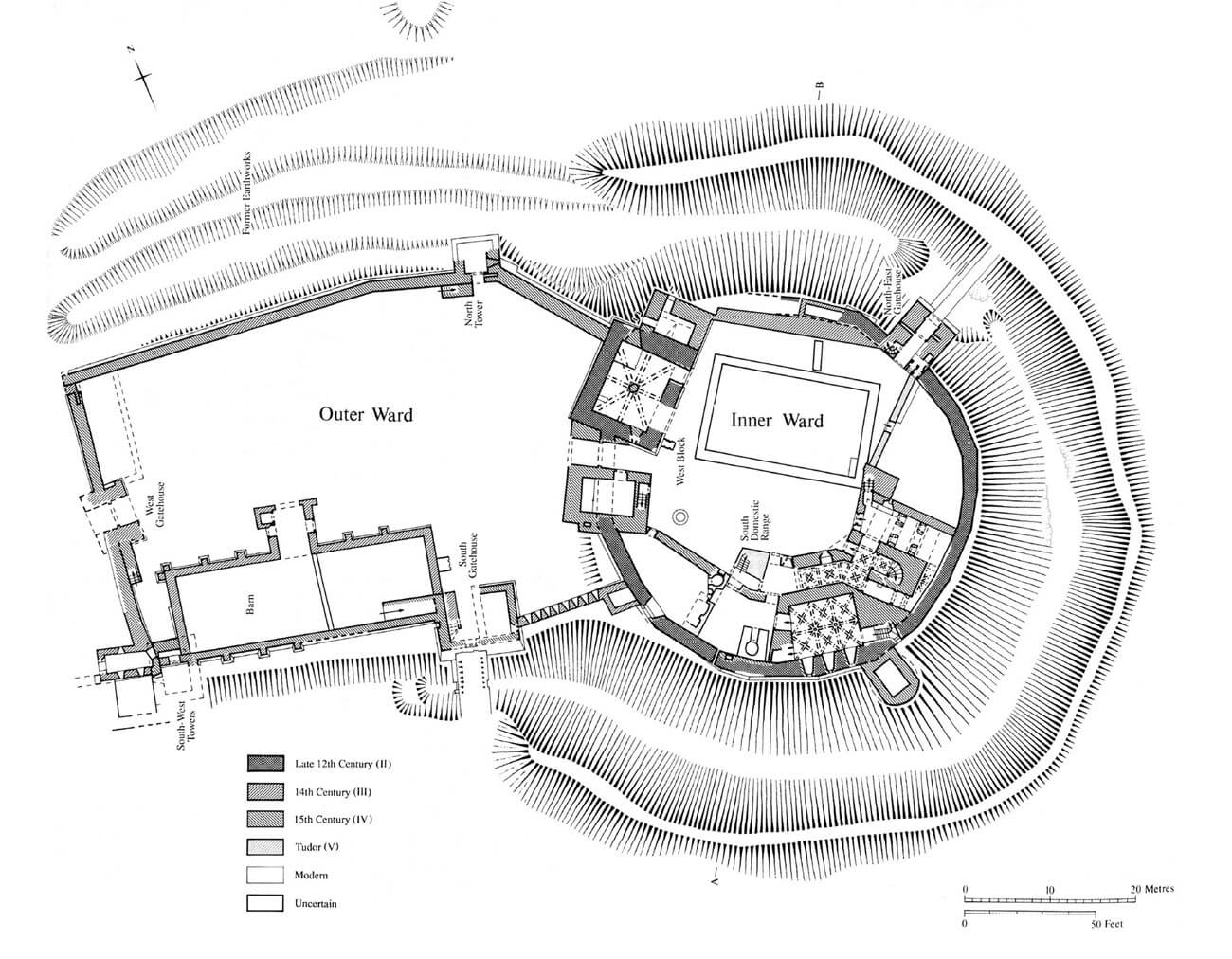

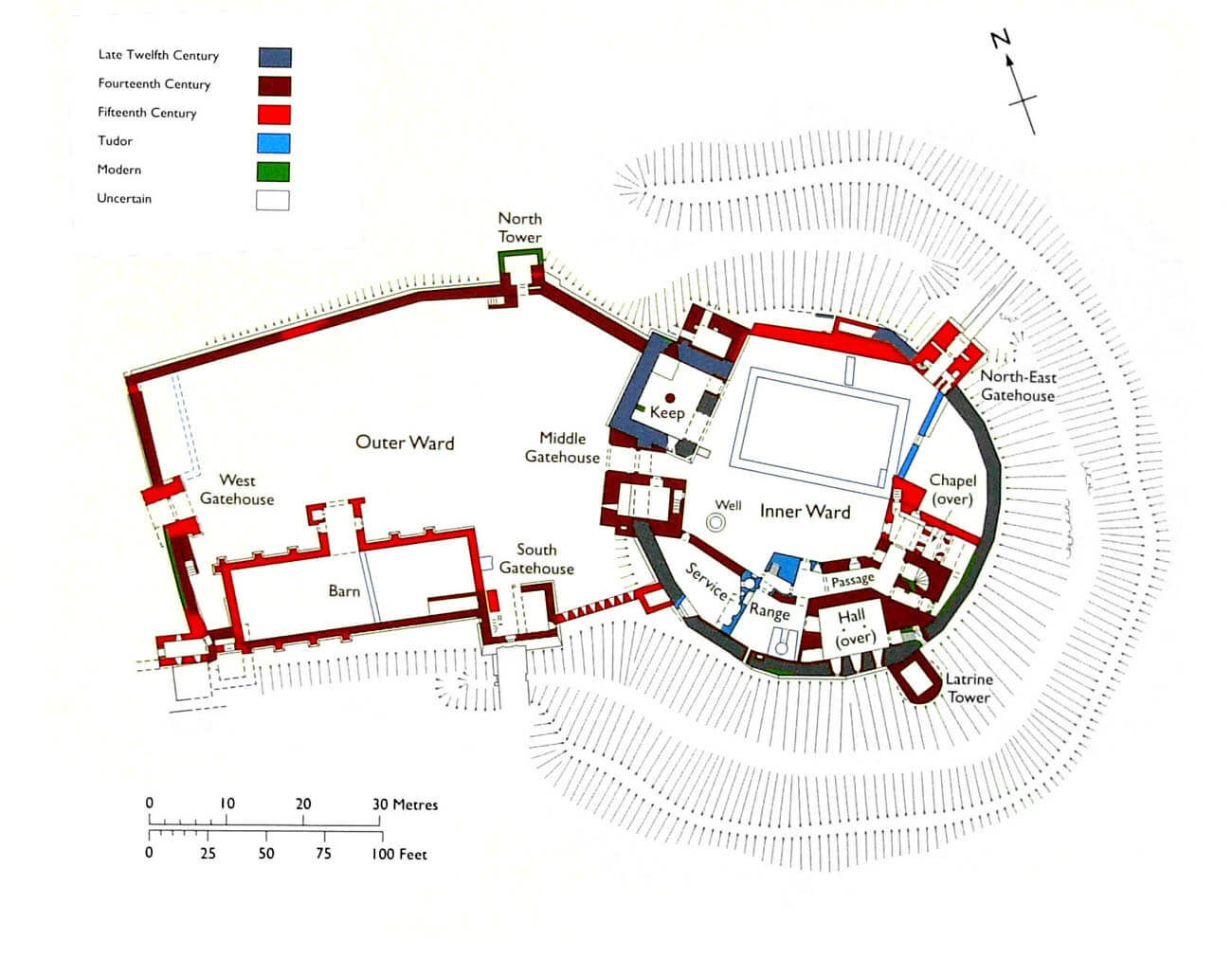

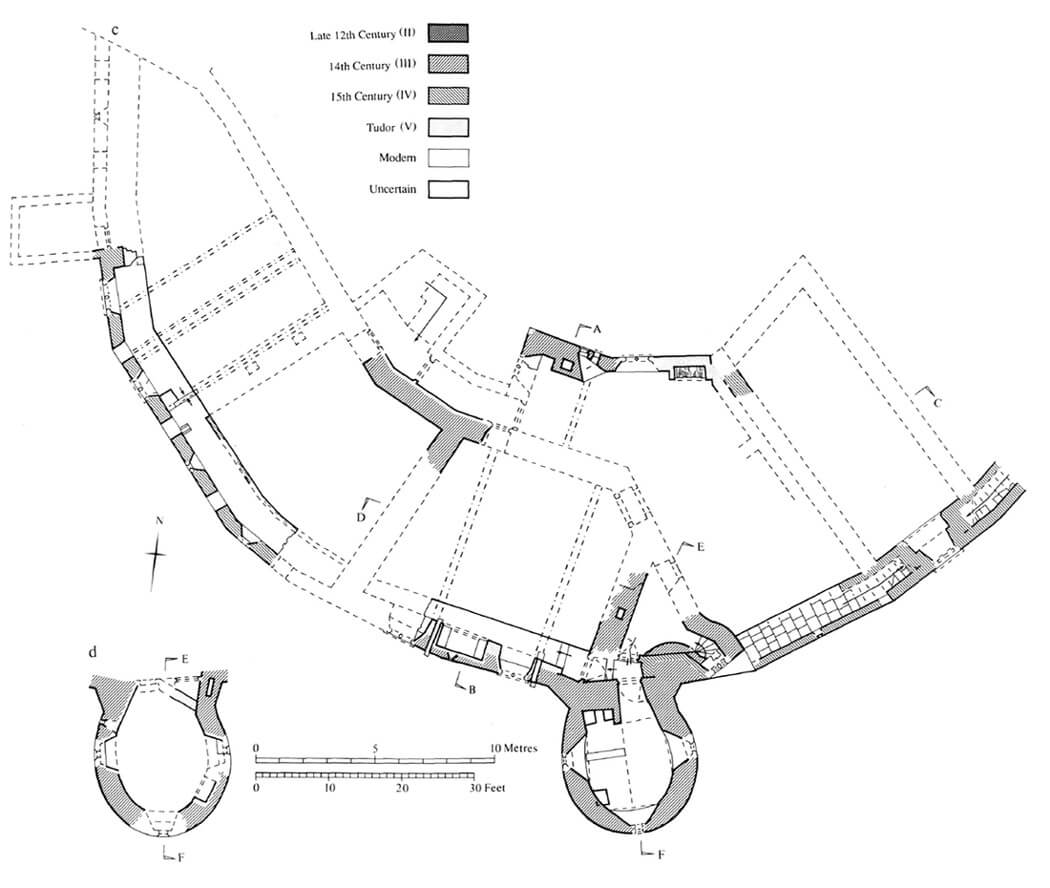

The original castle from the 12th century was a timber construction, but due to the area characteristic, exceptionally for the early Norman castles, it did not have the motte and bailey form. A flat area with a thin layer of soil made it impossible to obtain enough material to build a mound (motte). There were also no proper hills in the area, and the only watercourse on the eastern side, the Nant Bryn Glas stream, was small and some distance away. The oldest fortifications had to be in the form of a simple palisade, surrounding an oval courtyard, similar in size to Ogmore Castle, and slightly larger than in Newcastle Castle. The outer defense zone was probably a ditch, later significantly deepened and widened.

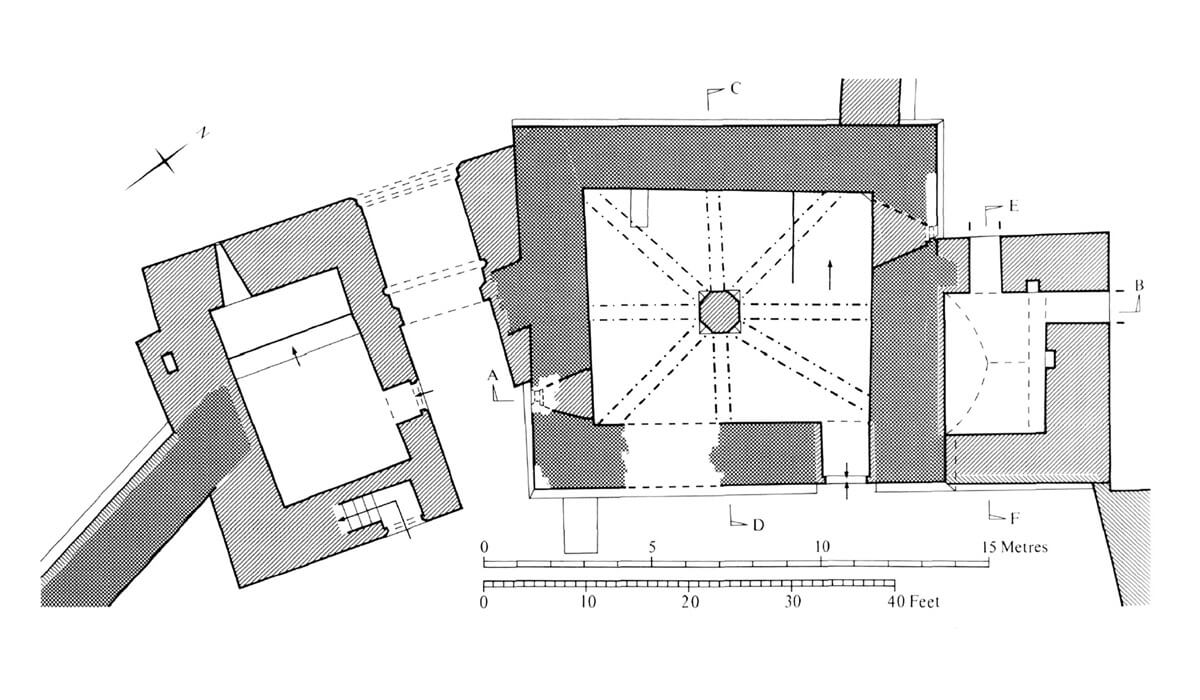

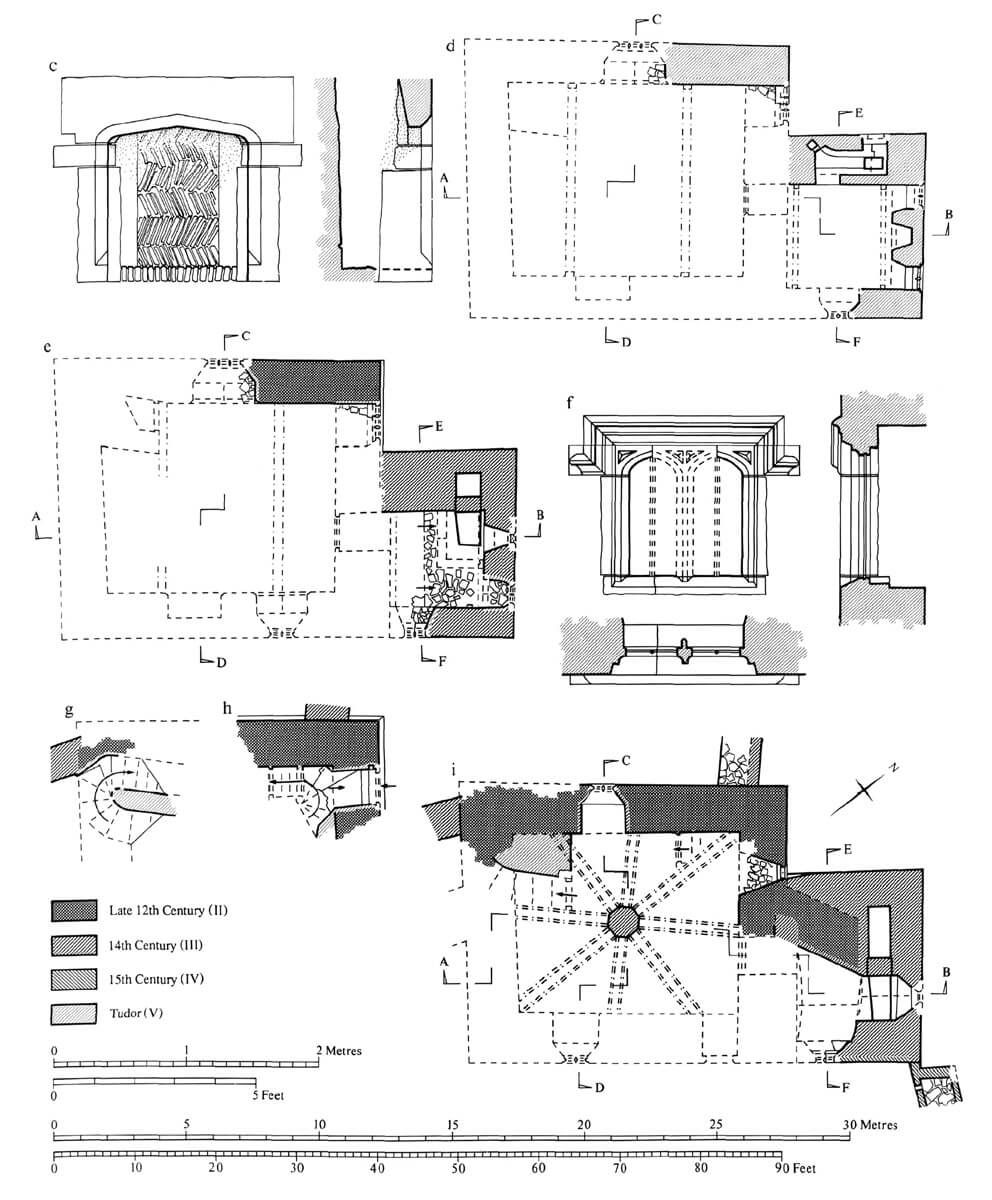

After 1180, a stone, four-sided keep of 12,2 x 10,2 meters (above the batter) and a defensive wall on an oval plan were erected, closing the courtyard of the upper ward with a diameter of about 40 meters. The wall was about 1.8 meters thick and about 5 meters high to the level of the wall-walk protected by battlement. The keep was quite unusually erected in its line, in the north-west part of the perimeter, close to the outer bailey, and not in the center of the courtyard, which also resembled the layout of the Ogmore Castle. The building flanked a gate located next to it, which was initially a straight passage created in the wall. From the west to the inner ward adjacent fortified outer bailey (initially timber) on a plan similar to a rectangle measuring 35 x 50 meters. The whole castle was surrounded by a ditch, which also separated the outer from the inner ward. Its average width was about 16 meters, and the depth ranged from 6 meters in the south to 4 meters in the northern part. The lower parts of the ditch to the west and south had to be carved into the rock, which probably provided some of the building material used during the works.

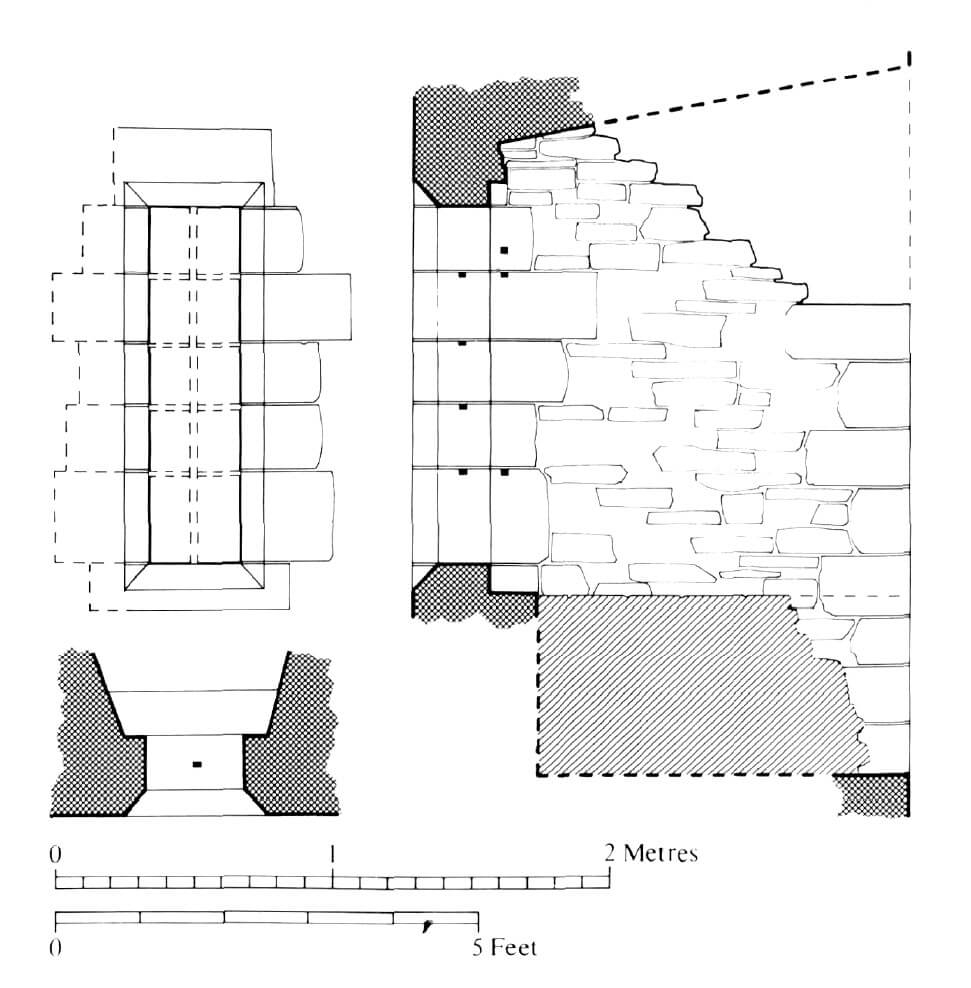

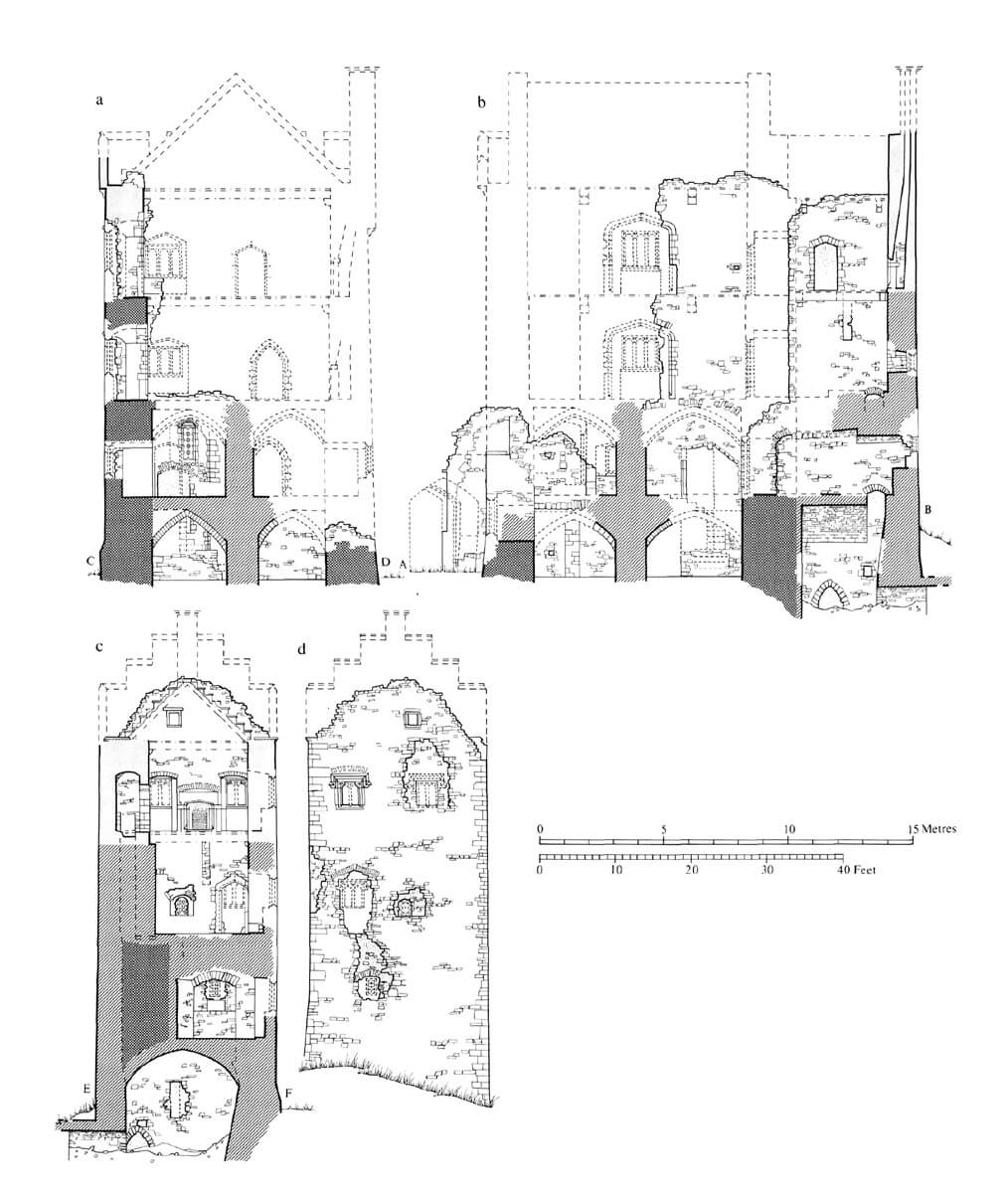

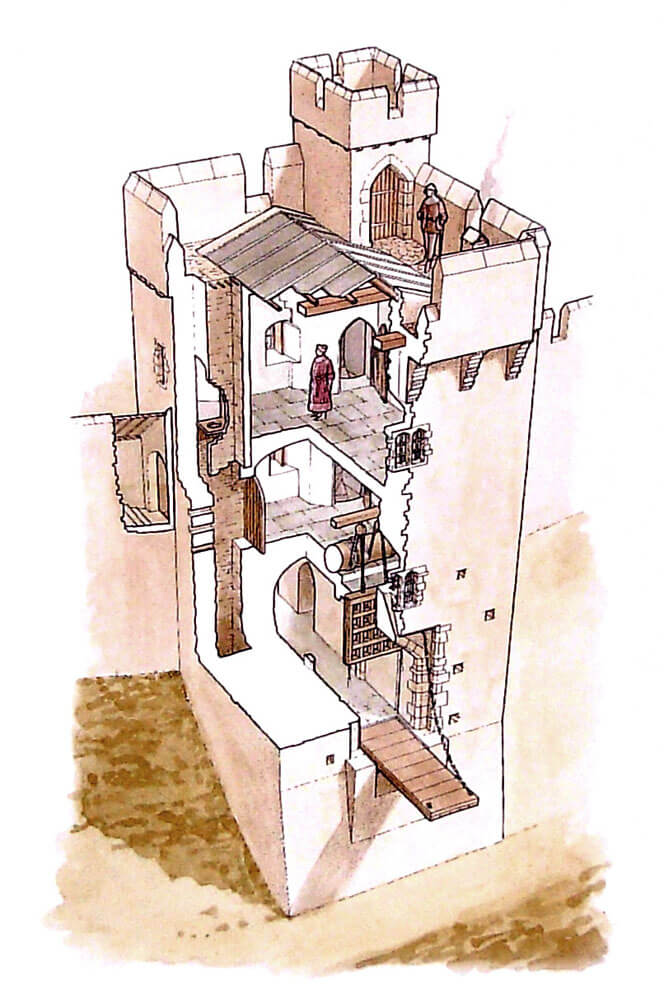

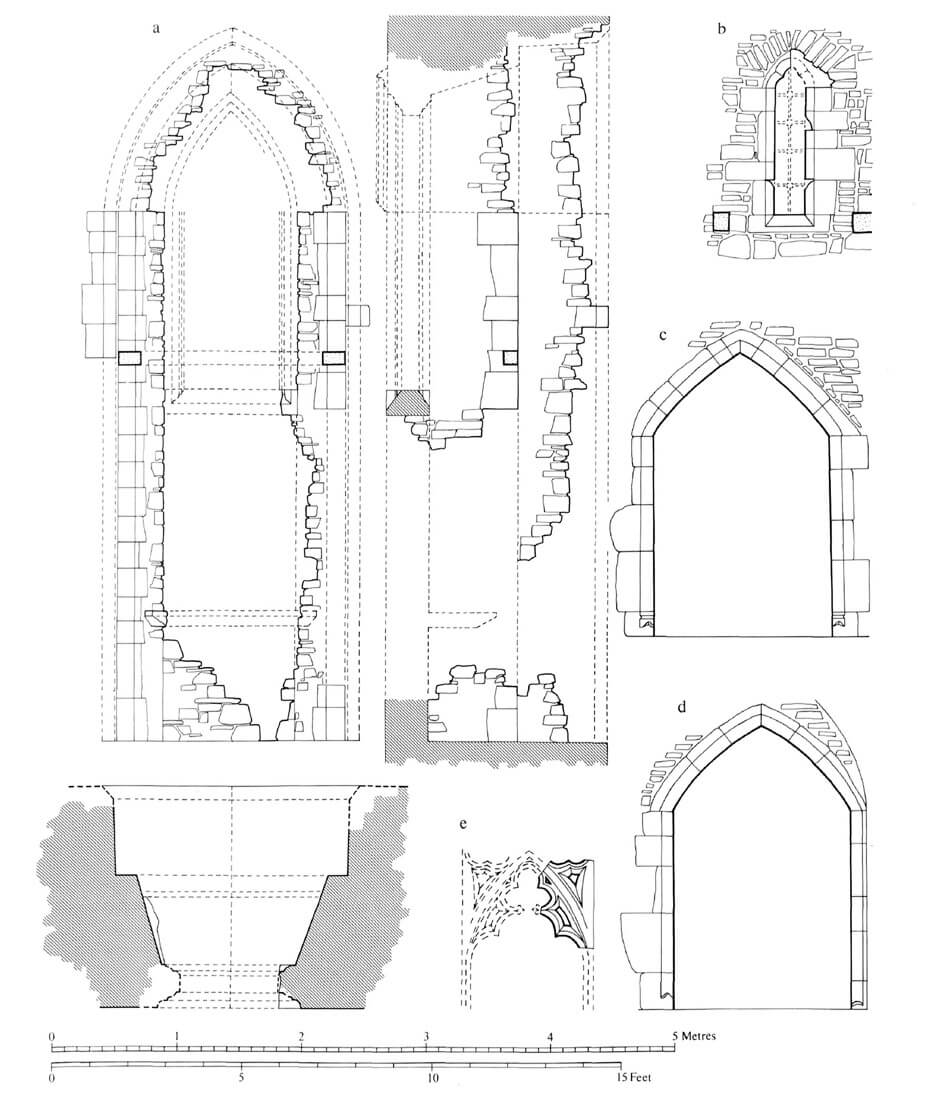

The keep inside walls 1.9 thick, originally had two floors above the ground floor or basement. The entrance led to it from the east (from the inner courtyard), from the level of the first floor, although already in the fourteenth century the portal on the ground floor was pierced. The lowest storey was originally only accessible through a hatch in the floor of the first floor. It was illuminated only by two slit openings, one directed towards the gate in the south, the other flanking the curtain of the wall in the north. At the beginning of the fourteenth century, a central, octagonal pillar was erected in the ground floor, which supported new rib vaults both in the lowest floor and in the chamber on the first floor. The ribs on the ground floor were massive and plain, while on the first floor they were decorated with chamfers. Along with their construction, a quadrilateral extension was added to the keep on the north-east side, which housed a spacious latrine on the second floor, a slightly tighter, irregular, segmentaly vaulted room with a latrine on the lower floor and a chamber at the bottom covered with a pointed vault. Both in the annex and in the keep itself, Gothic windows were probably inserted in the 14th century, placed from the inside in deep recesses. The first floor of the keep was connected by a semicircular portal with a wall-walk in the crown of the defensive wall. Unlike the economic ground floor, it probably served a residential function, as did the second floor covered with a wooden ceiling. At the beginning of the 16th century, Tudor-style windows were inserted on the upper floors of the keep, a staircase was created in the south-west corner, and an additional third floor was added to both the keep and its northern annex, thanks to which it reached 18 meters high to the level of the parapet. It housed a fireplace and a latrine in the keep, and was separated by a wooden ceiling.

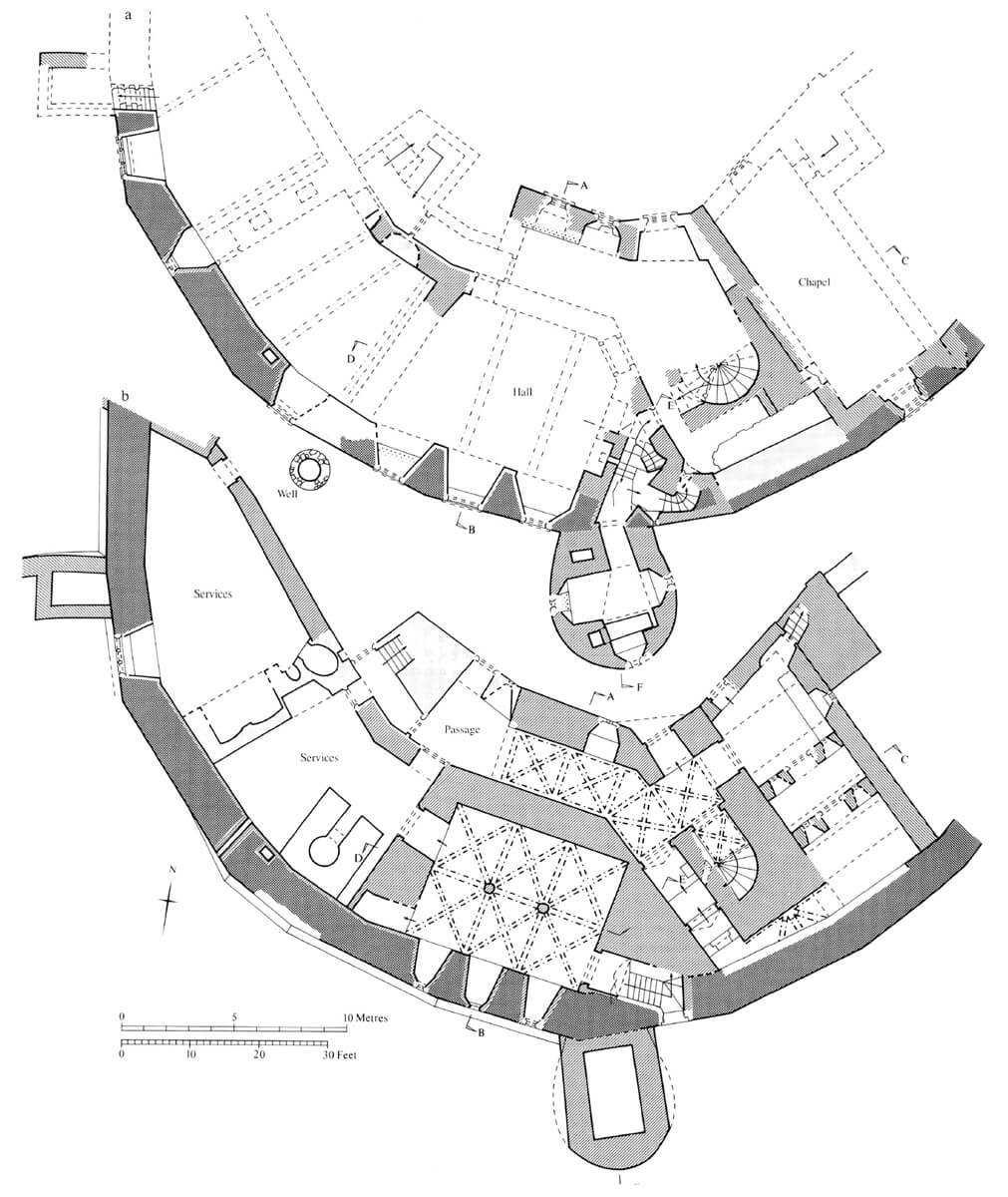

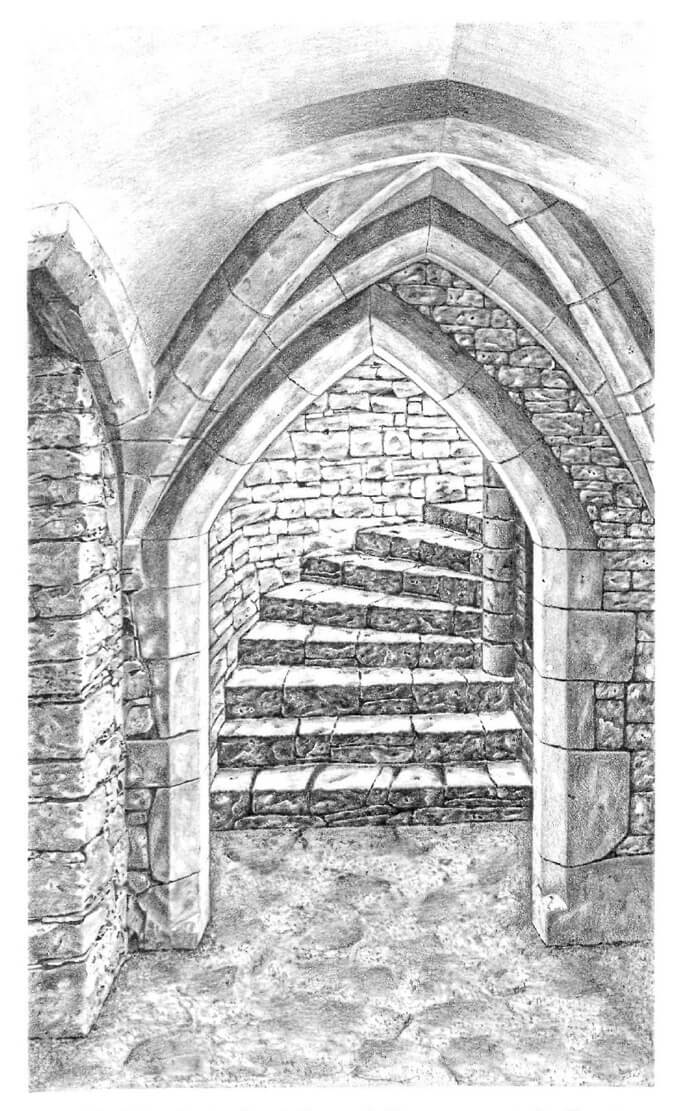

In the first half of the 14th century, a gatehouse was added at the entrance to the upper ward, replacing the earlier passage from the end of the 12th or 13th century. It was located at a slight slant to the adjoined keep. From the west it was preceded by a moat, towards which it partially protruded in front of the perimeter of the walls. Most likely, a drawbridge was placed over the moat. The gate passage itself was led in the northern part of the building, only a short fragment of the wall at the keep wall was added to compensate for the deviation from the axis of the old tower and to be able to lead a straight 10-meter-long passage. Inside the latter, there was a pit to which the rear part of the drawbridge was hidden when it was lifted. After about 3 meters, the passage was closed with a portcullis, and then with a wooden gate, behind which, turning right, one could enter from the gate passage to the guard’s room. In the thickness of the eastern wall of this room there was a portal leading to the courtyard (but not connected to the ground floor room) and stairs leading to the first floor of the gatehouse. The guard room in the ground floor also housed a four-sided water tank at the western wall and latrines with outlets facing south towards the moat. The room on the second floor of the building had to contain a mechanism for operating the portcullis.

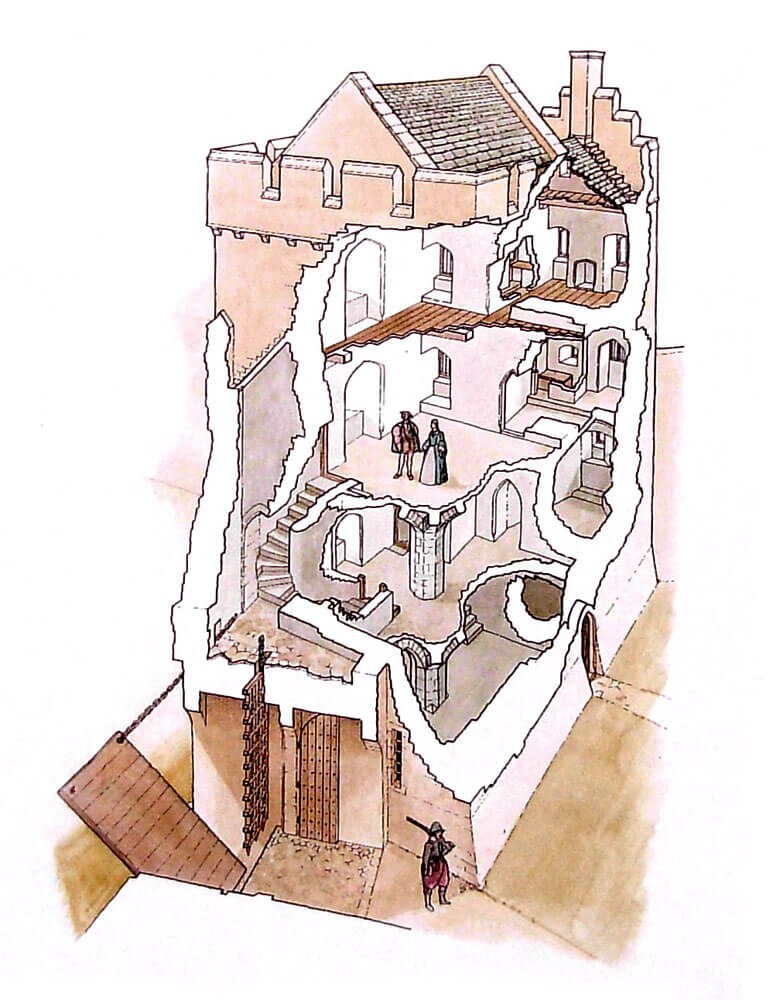

Since the fourteenth century, the main utility and living rooms were located in the southern wing, attached to the inner face of the perimeter wall. From the side of the courtyard, the entrances led through the vaulted lobby, extended to the west in the 16th century to connect with the service rooms. The latter had an irregular shape and two rooms in the ground floor, accessible through two portals at both ends. Initially, the division into rooms was probably fulfilled by a wooden partition screen, in the 16th century replaced by a stone wall, which allowed to modernize the equipment of the local kitchen. It was located in the western room and had two fireplaces and two ovens. In the eastern chamber there was a huge lime kiln of uncertain dates, a sixteenth-century fireplace in the western wall, and a drain in the perimeter wall. Above these rooms, holes for ceiling beams indicate the functioning of two more floors. On the west side in the 15th century in the corner between the outer bailey wall and the wall of the upper ward a latrine turret for service and garrison was added.

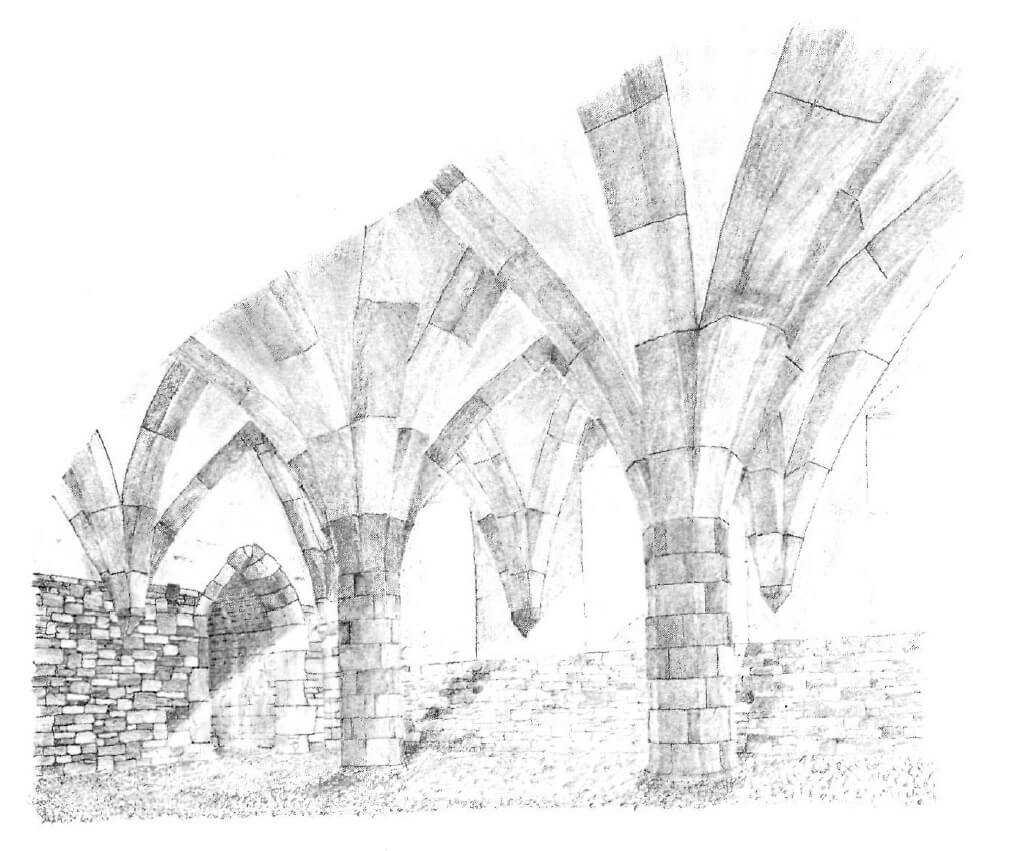

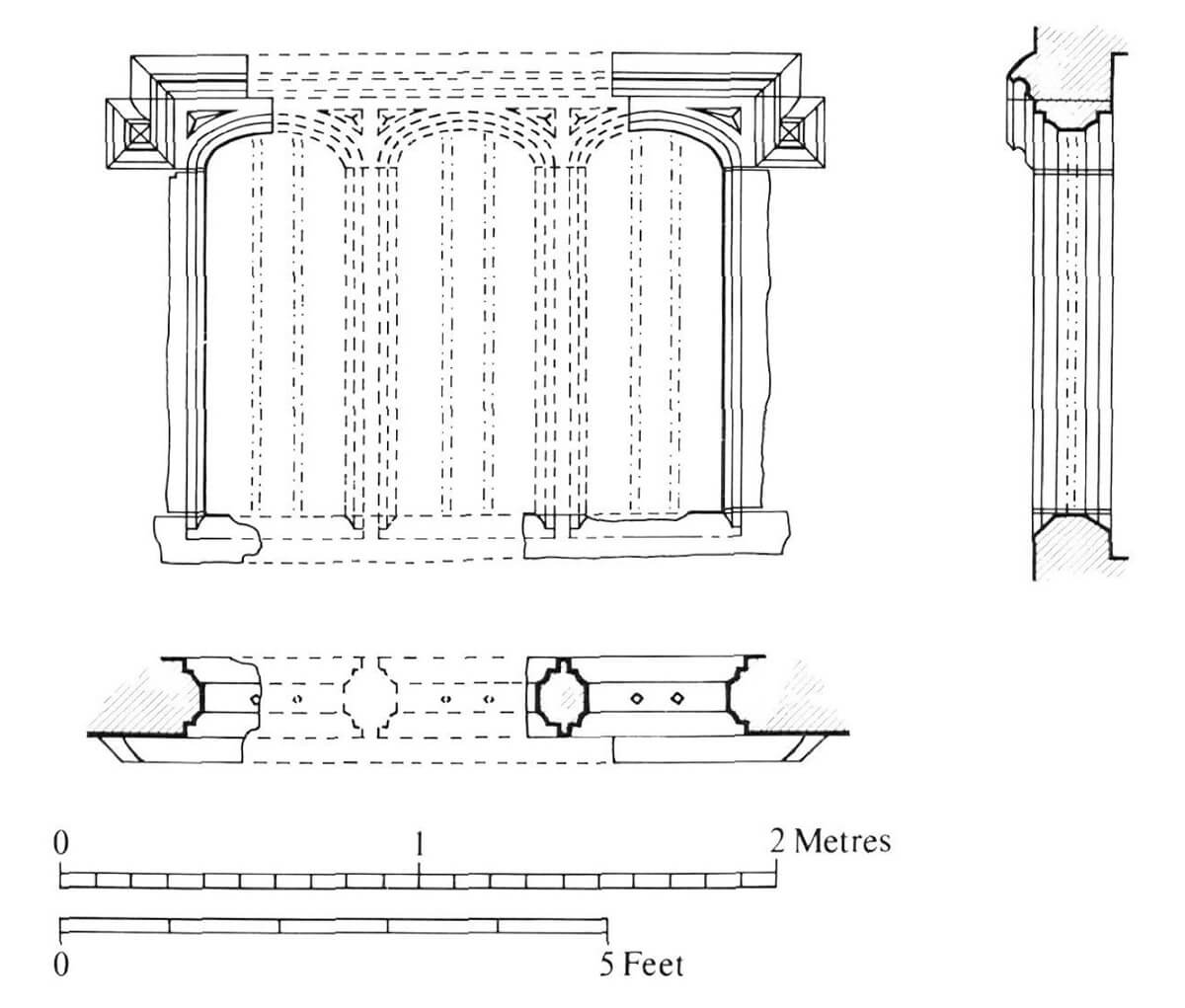

The eastern part of the southern range was occupied by a vaulted pantry-cellar chamber, located under the main representative chamber – the hall and the main staircase connected to the passage vestibule. This main communication node of the wing had as many as four pointed portals and passages: stairs down to the ground floor under the 15th-century chapel, doors to the courtyard, doors into the vestibule and further to services, and a shorter passage to the ground floor under the chapel. The first of these passages would seem of little use, but three ribs and a corbel in the eastern part would indicate an unrealized desire to build more rooms there. The cross-rib vault of the basement chamber was supported by two central, octagonal pillars and numerous wall consoles, and the lighting was provided by three small windows. The entrance to it led from the west, from the service rooms. From the basement, the stairs also led to the semi-circular latrine tower which was fully extended in front of the perimeter (probably to the postern gate before its construction). The hall, although small in Coity (9 x 7 meters), was the center of home life in the castle – feasts were held there, important ceremonies were organized, and guests were greeted. It was lit from the outside with three large windows set in deep recesses, and it was covered with massive beams of a wooden ceiling. As the most important room since the fourteenth century, it was accessible through a large staircase on the north-eastern side. From the north, it was adjacent to the narrow living rooms on the two upper floors, both heated with fireplaces. Another private living room was above the hall.

The role of the southern latrine tower, as the name suggests, was primarily to provide sanitary facilities in the castle, and at the same time to flank the adjacent curtains. Its interior on the lower level was four-sided, up to 8 meters high and served as a pit for waste. The three upper storeys were already oval, separated by vaults set on the eastern and western corbels. Good lighting was provided by three window openings on each floor, moreover, there was a latrine on the first floor, two latrines on the second floor, and a latrine on the third floor and a fireplace. The first floor was accessible from a triangular vestibule by an auxiliary staircase, near the eastern wall of the hall. Similar vestibules by the staircase were also on the upper floors.

In the first half of the fourteenth century, the outer bailey was surrounded by a stone defensive wall, reinforced with four-sided towers on the north, south and in the south-west corner. The entrance to the courtyard then led through a straight passage pierced in the middle of the western curtain. The castle walls were thicker on the more vulnerable west and north sides, while the southern curtain was only 0.9 meters thick. The castle’s builders predicted that the potential attacker would attack from the higher north side. Near the north-west corner a small postern gate was created, closed with a drawbar placed in a hole in the wall. Perhaps it was originally obscured by a rectangular building added to the curtain wall, but it is uncertain in what period it was erected.

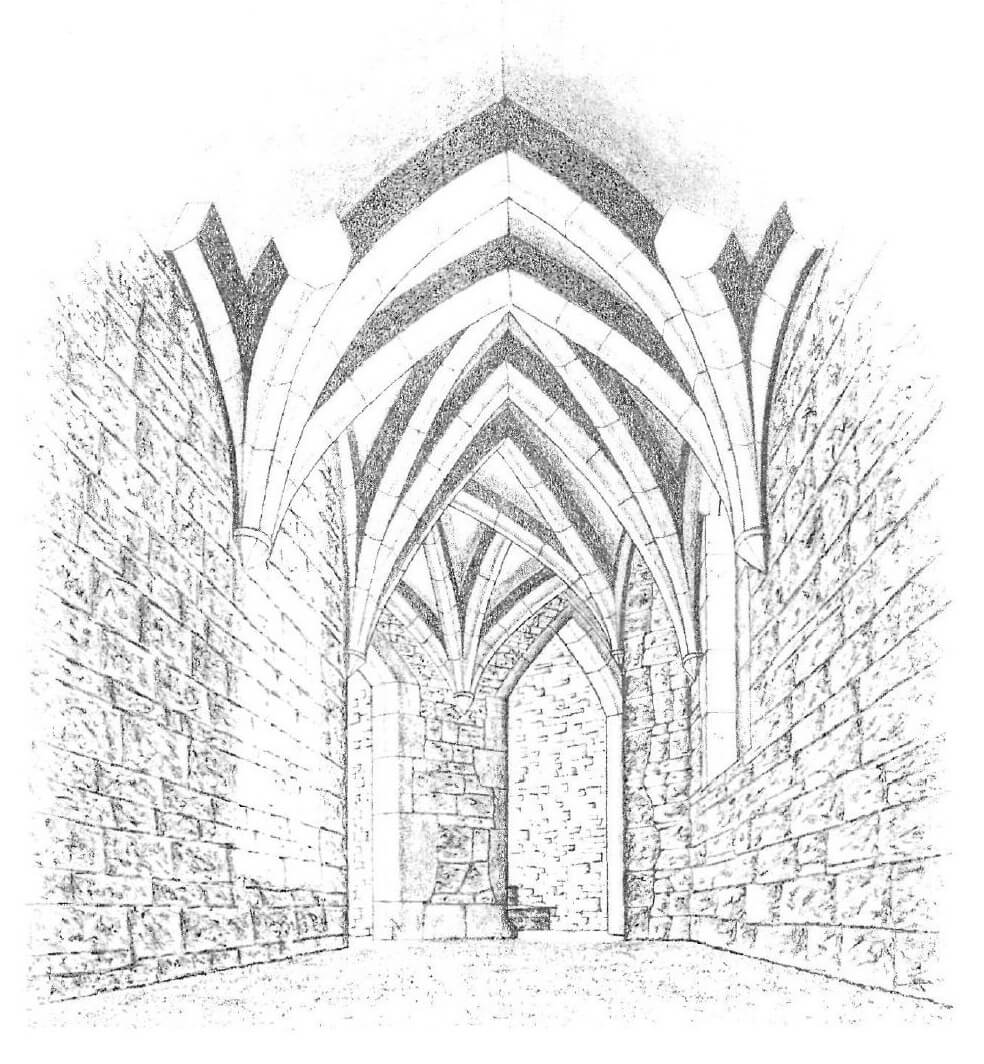

After the destructions at the beginning of the 15th century, the northern wall of the upper ward required rebuilding, with the new curtain erected as straight, not rounded. During these works, a new gatehouse on the north-eastern side and a chapel were also erected. Work on the latter began in the fourteenth century, but was not completed then. The gatehouse received a four-sided form with dimensions of 7 x 6.3 meters, completely protruding in front of the perimeter of the 12th / 13th-century wall, with a passage in the ground floor and two upper floors topped with a parapet with a battlement mounted on corbels. The holes between these corbels formed machicolation. The façades of the tower were pierced with numerous putlog holes, as well as small, single and doble-light windows. The passage was originally vaulted, closed with a drawbridge, retracted into a four-sided recess with two corner openings for chains. A portcullis was located close to it and a door approximately in the middle of passage length. In addition, the control was provided by a hole pierced in the floor of the window recess on the first floor, directed at the portcullis. There was no guard room on the side of the passage, but in the south-west corner in the wall thickness there was a small chamber. The raised portcullis was located on the upper floor, also vaulted, well-lit and connected to the wall-walk. There was no room for a fireplace, but the guards could use the latrine. Better living conditions were provided by the top floor, where there was a fireplace, large windows on each side of the room and a latrine. The staircase (probably built in a slightly later period) provided a connection between the floors and the upper defensive gallery, protected by the aforementioned battlement based on a breastwork with machicolation. Even there, in the south-eastern corner, there was a latrine for the guards.

The chapel building had two floors with an entrance to the ground floor directly from the courtyard. From there, one could go through the ogival portal to the southern wing or, using the corner staircase to the first floor of the chapel. The corner staircase was added after the building was completed, and initially it was possible to enter its first floor only through the stairs in the southern wing. Also shortly after finishing the ground floor, the chapel was divided into three rooms by inserting two partition walls with central portals and side openings (quadrilateral, grilled). Most likely, these rooms served as pantries and storage rooms. Stone wall corbels suggest that the ground floor was originally planned to be vaulted, the chapel itself was also to be much longer and protrude from the east in front of the perimeter of the walls, but these intentions were never realized. The upper chapel was placed on a wooden ceiling and illuminated by a large ogival window.

At the beginning of the 15th century, the western gatehouse and a new tower in the south-west corner were erected on the outer bailey. The west gatehouse was not a very strong and sophisticated structure. It was erected as a four-sided with a barrel-vaulted gate passage closed with a portcullis and centrally placed door and preceded by a drawbridge over the moat. The room on the first floor of the gatehouse was illuminated by a window in the eastern wall facing the courtyard of the outer bailey, while from the opposite west side there was probably a window or loop hole directed into the foreground. The room was covered with a flat, wooden ceiling mounted on stone corbels, above which there was also an attic. The entrance to the first floor of the gatehouse led from the south, along the 14th-century stairs at the inner face of the perimeter wall. There was no connection between the gate floor and the north curtain.

In the fifteenth century, the south-west corner tower was dismantled to give way to a postern gate pierced in the side wall, while on its western side a new rectangular, narrow tower was erected, strongly protruding towards the moat and flanking the west gate. In its lower part, an opening was created suggesting that the moat was originally filled with water that flowed under the tower, possibly also serving as a mill. The façades of the tower – mill were pierced with slits in the ground floor and small four-sided windows on the first floor, and the entrance to it was pierced in the old curtain of the bailey. The last change was the transformation of the southern tower into a gate and the addition of a new fragment of the wall leading to the upper ward, pierced with eight arrowslits directed towards the southern section of the moat (which was probably already drained at that time). These openings had an unusual form similar to a cross, in which the horizontal slit was separated by two small stones. At the wall of the upper ward, the curtain of the outer ward was connected to the corner latrine annex, the same height as the walls of the main part of the castle. The southern gatehouse (former tower) received a passage in the ground floor, above which there was a chamber illuminated by two windows topped with trefoils. Higher up there was a parapet with battlement based on protruding corbels, defending the wall-walk and a gable roof. In the corner of the chamber there was a latrine facing the moat.

At the same time, a large barn was built in the courtyard of the outer ward, which used the southern curtain as one of its walls. On the outer south side, this wall was reinforced with buttresses, as was the wall from the courtyard side. The entrance to the barn led through the northern vestibule with two entrances on the sides in the ground floor, probably to facilitate the storage of grain. In the north-west corner of the vestibule, a small chamber was created – a recess, intended for the barn supervisor. On the floor of the vestibule there was a room, probably also used by the clerk supervising the storage of goods. The erection of the barn meant that inside it there were 14th-century stairs leading to the crown of the defensive wall and to the southern gate.

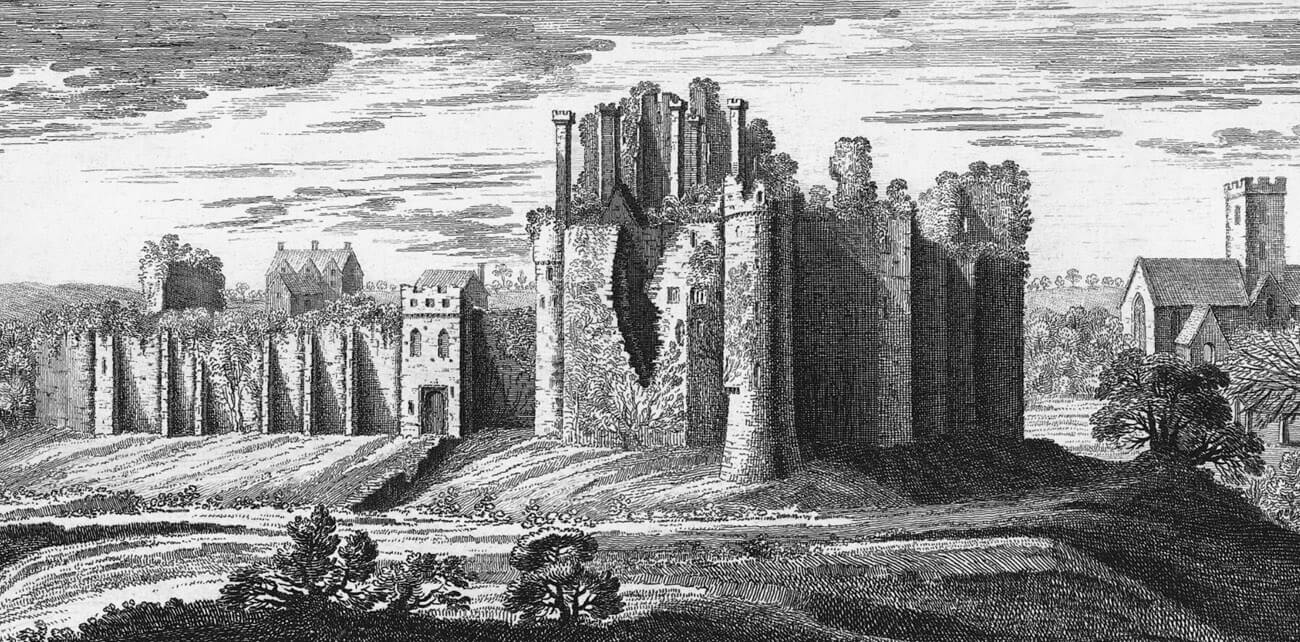

Current state

The castle has been preserved to modern times in the form of a ruin. In the best condition has survived the north-east gatehouse of the upper ward, a lot has survived from the south range, two walls of the keep are also visible. There is a clear layout of the outer ward with a defensive wall practically on the entire length and relics of a large barn. The ditch is visible around the upper ward; it was leveled at the outer ward, except for the northern and partly southern sections. The ruins of the castle are under the care of the Cadw government agency and are open to the public. On the north-eastern side of the castle is the 14th-century parish church of St. Mary.

bibliography:

Kenyon J., The medieval castles of Wales, Cardiff 2010.

Kenyon J., Spurgeon C.J., Coity Castle, Ogmore Castle, Newcastle (Bridgend), Cardiff 2001.

Lindsay E., The castles of Wales, London 1998.

Salter M., The castles of Gwent, Glamorgan & Gower, Malvern 2002.

The Royal Commission on Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales, Glamorgan Early Castles, London 1991.