History

The first small timber castle was built by Gerald of Windsor around 1108-1115 on the lands taken by the Anglo-Normans from the Welsh kingdom of Deheubarth. It is known that in 1108 he erected a fortification called Cernarth Bychan, sometimes identified with Cilgerran. A year later, the stronghold was captured by the Welshman Owain ap Cadwgan from Powys, who, on the occasion, kidnapped Nest, the wife of Gerald, while he was forced to make an undignified escape down a latrine shaft. Probably after Owain’s withdrawal, Gerald returned to Cernarth Bychan, but this name ceased to appear in later historical accounts.

The first certain record of an already partially stone stronghold comes from the time of its conquest by the Welsh led by Rhys ap Gruffydd in 1165. The following year, the Anglo-Normans tried to recapture the castle twice, but suffered only large losses and had to retreat. In 1172, King Henry II concluded an agreement with Rhys, which normalized the political situation and led to the temporary truce. The death of Rhys ap Gruffydd in 1197 weakened Deheubarth, torn by the dynastic struggles of his heirs. Thanks to this, the Anglo-Normans were able to recapture Cilgerran in 1204, when William Marshal, the first Earl of Pembroke, drove out son of Rhys, Maelgwn ap Rhys. Marshal decided to make repairs, but they proved ineffective, because the castle was re-conquered after a day-long battle in 1215 by Llywelyn the Great. It was not until the eldest son of Marshal, also William, eventually regained the castle, arriving with large forces from Ireland in 1223. In order to protect against the next Welsh invasions, William began a thorough rebuilding and extension of the castle. Cilgerran was never taken by the Welsh again, though in 1258, when the English forces were defeated nearby, the castle had to repel the princes of Deheubarth.

After the death of Ansel Marshal, the sixth Earl of Pembroke, the castle passed into the hands of the de Cantilupe family in 1245. Another change occurred in 1273. After the Cantilupe family expired, the stronghold was given to the Hastings family, although due to the minority of its members, King Edward I officially took care of the castle. In the first half of the fourteenth century, the condition of the castle was poor, it was even described as close to ruin. The situation changed somewhat in the second half of the fourteenth century due to the Anglo-French war and the expedition of John de Hastings, Earl of Pembroke and Lord of Cilgerran to Aquitaine. He was defeated at the coast of La Rochelle, which caused fears of retaliation by the French. For this reason, in 1377, Edward III ordered repair work to be carried out at the castle, although ultimately no invasion of Cilgerran took place. The English king was then the custodian of the minor representatives of the Hastings family.

The last member of the family, John de Hastings, died in 1389, and the Crown’s castle was probably damaged during the Welsh rebellion of Owain Glyndŵr in the early 15th century. From that moment, references to Cilgerran ceased to appear, and the castle itself was probably abandoned at that time. There is no information that it would be used during the War of Roses or during the 17th century civil war.

Architecture

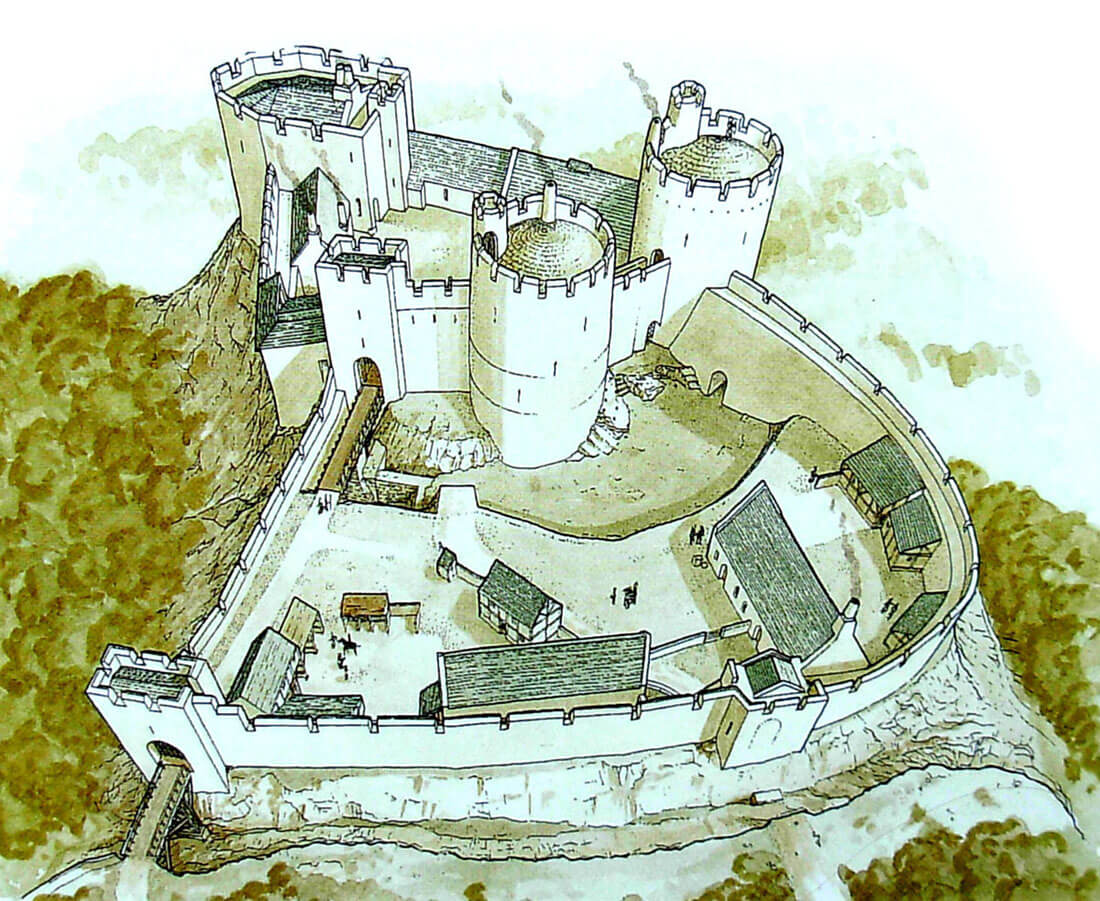

The castle was erected on a rocky promontory above the Teifi River, north and east side directly on the cliff. The deep valley through which the river flowed meant that the castle was practically inaccessible from its side. Also from the west side, the slopes passed steeply towards the Plysgog stream, which flowed into Teifi at the foot of the hill.

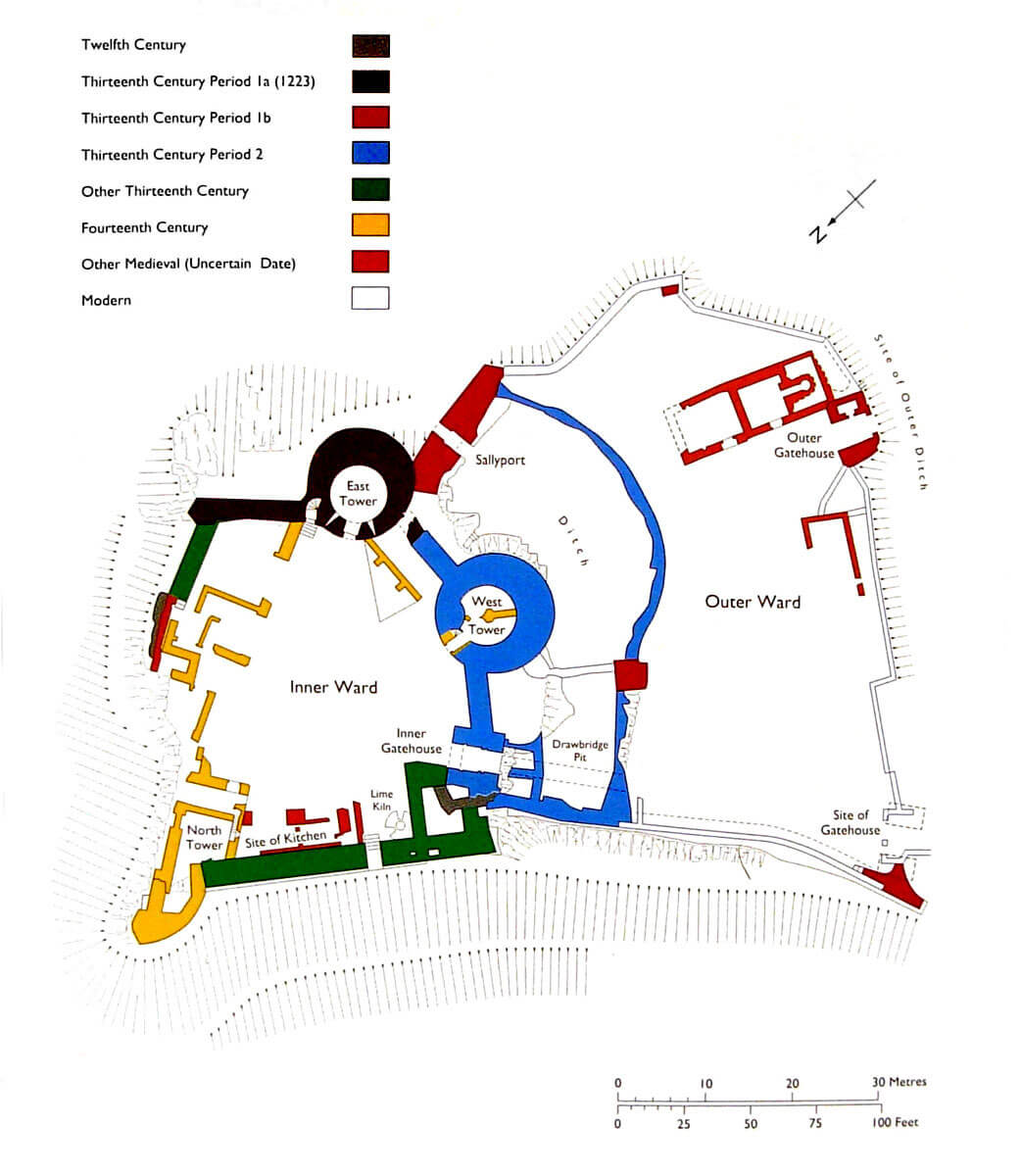

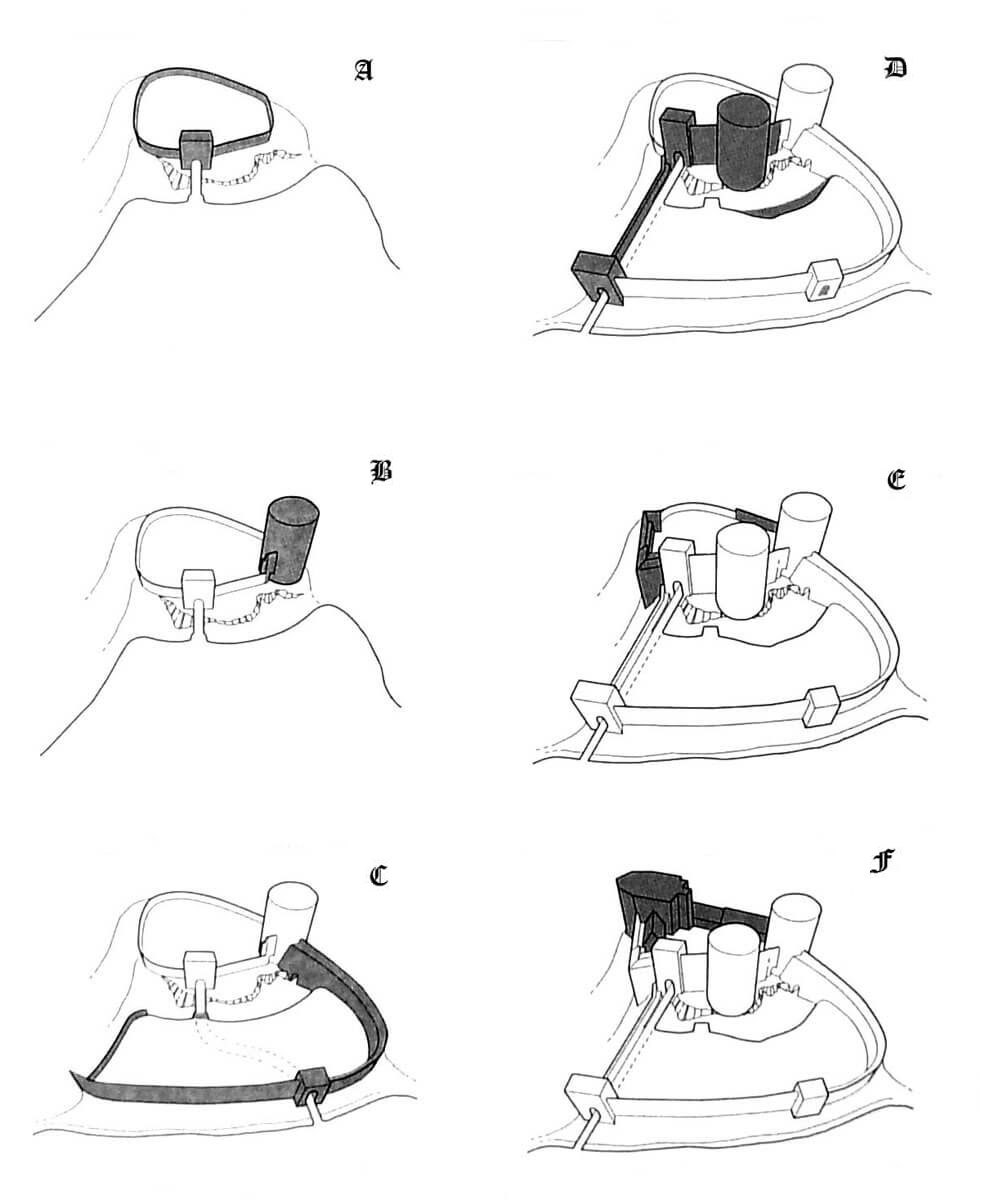

It is not known exactly what the first timber castle from the 12th century looked like. Perhaps it had the form of a wood and earth fortification (ringwork) with a gatehouse to which a bridge spanned over the ditch led. This dry moat cutting off the promontory from the rest of the plateau also became the basis on which the expansion of the castle was based. The earliest brick fragments in the form of stones joined with clay mortar, dating back to the 12th century, were found near the entrance gate and at the northern edge of the hill.

A thorough replacement of timber fortifications with stone one took place since around 1223. It probably had a form similar to the shield wall, located just behind the ditch, on the most endangered southern side. From the side of the cliffs, the castle was less fortified because terrain provided sufficient protection. The shape of the castle resembled the early stage of the construction of Pembroke Castle, erected by William Marshall the older twenty years earlier. In both strongholds, the entrance to the cut-off promontory was placed in the gatehouse located on the left, extreme side, probably to make it difficult to use the shields to potential attackers.

Around the 1223 , a massive cylindrical tower with an internal diameter of 6.4 meters was erected in the eastern corner of the perimeter of the walls. Thanks to large rooms equipped with fireplace and relatively good lighting, it could perform residential functions. After the death of William Marshal the younger, one of his brothers (perhaps earl Gilbert before 1241) erected a new quadrilateral gatehouse and a second, western, also cylindrical tower of similar dimensions as the eastern one (outer diameter 11.8 meters), but significantly extended beyond the perimeter of the walls towards the ditch. This rather unusual arrangement of two massive towers with donjon functions may have been caused by the large distance from the gate to the eastern tower and difficult flanking due to the bent of the central part of the southern curtain wall.

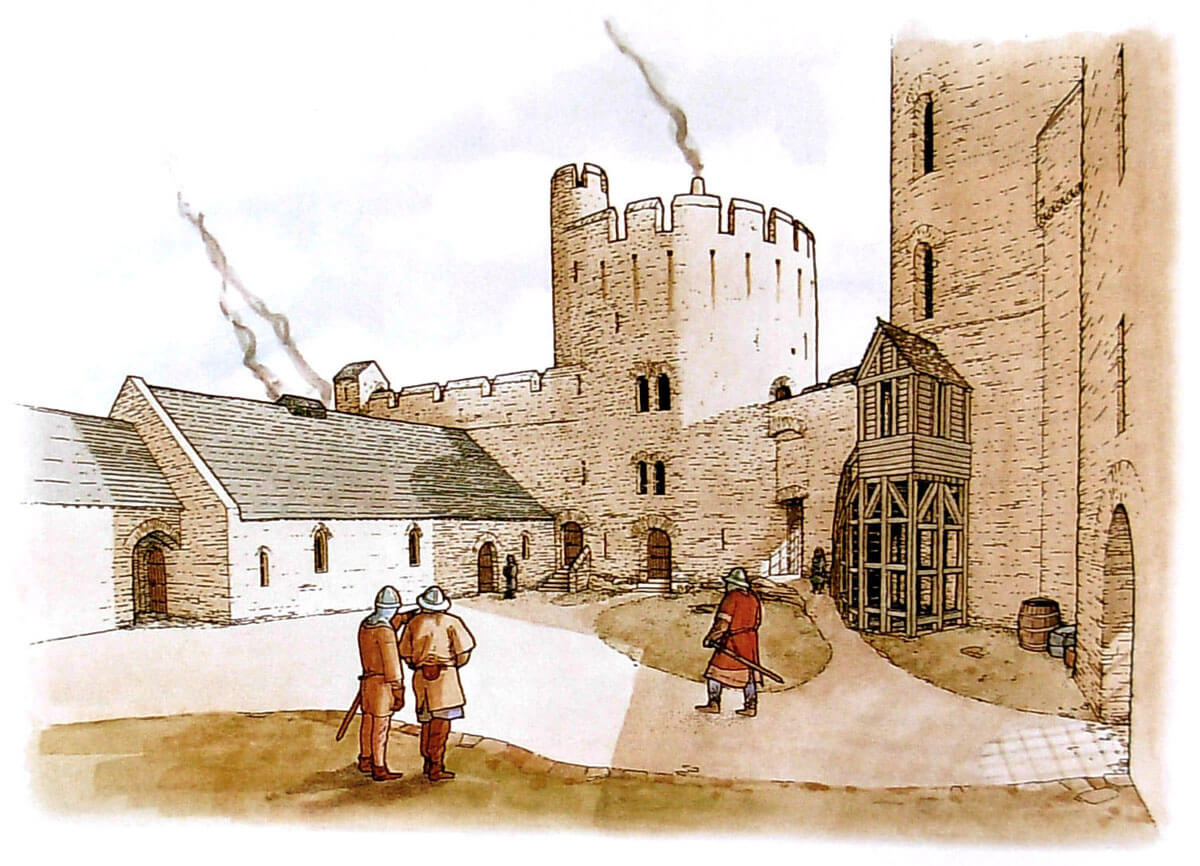

Two large cylindrical towers had three upper floors above the ground floor. Since the eastern one was built first, it initially served as a keep, although it was unusual to enter it from ground level. The explanation for this was the fact that the ground floor of the tower was not connected to the first floor or accessible only by a ladder. Internal communication between the upper floors in the eastern tower was provided by a spiral staircase to which a separate entrance portal led straight from the courtyard. Perhaps at the top of the tower it turned into an observation turret. Only one fireplace was installed in the tower’s highest chamber. From the south side it had only arrowslits, but from the courtyard side there were already larger two-light windows illuminating the interior. From the level of the second floor you could get to the crown of the defensive wall, which on the northern side ended in the form of a spur with a pair of chutes functioning as latrines. Next to the tower on the south side there was a small wicket protected by a portculis, which led to a ditch and further to the postern gate in the outer wall.

The western tower originally only had an entrance from the first floor level, accessible through a wooden, external staircase in the form of a roofed vestibule just before the entrance portal. Originally, the ground floor was only accessible through the ceiling hatch and illuminated by a small ventilation shaft. In the fourteenth century, in order to facilitate communication, the portal at the courtyard level was pierced and the lower floor of the tower was divided by a partition wall. Stone stairs in the thickness of the wall began to lead to the tower first floor. The first and second floors, also accessible through staircases, were equipped with fireplaces and single-light windows from the courtyard side. The window was also pierced on the third floor, but the room did not have a fireplace. From the level of the second floor, the passage with arrowslits led in the thickness of the defensive wall to the gatehouse. Another wall-walk led to the gatehouse in the crown of the defensive wall from the third floor of the western tower.

The new thirteenth-century gatehouse was moved a little further west compared to the older one. It had two floors above the ground floor, a drawbridge and two portcullises. A defensive wall connected it and was flanked by a round western tower. On the first floor in the vaulted room, probably a chapel was placed, because there was a piscina or a sink for washing dishes used during mass. The portcullis would then have to be lifted inside the chapel, but other such examples are known, e.g. at Caernarfon Castle or at the Marten Tower of Chepstow Castle. The top of the gatehouse was in the form of a breastwork with a battlement based on protruding corbels.

In the fourteenth century, the inner courtyard buildings were concentrated at the north-west and north-east curtain. After passing the gate to the left there was a place where mortar for construction was made, and then the kitchen building was located. The northern corner of the castle was occupied by a polygonal tower, probably residential, protruding beyond the perimeter of the walls. The castle from the side of the river closed the defensive wall, at which height about 3 meters was a wall-walk for defenders. A smallwicket gate was pierced in the wall for escape or descent to the Plysgog valley.

The outer ward in the south was separated from the upper castle by a ditch. Its fortifications consisted of an external ditch and a defensive wall with a gatehouse on the south side of dimension 8 x 5 meters with a passage and a small room of the guards in the ground floor. This small building was probably closed only by wooden door and a drawbridge and belonged to the earlier phase of the castle. At a later stage, probably in the 13th century, it was replaced by a new gatehouser located in the western corner of the outer bailey. Its protection was more sophisticated, in addition to the drawbridge it was also closed by a portcullis. An additional buildings of the outer ward was a pair of houses, probably of economic purpose. The eastern one had a rectangular shape and was divided in the ground floor into three rooms, one of which had an oven. The upper part of the building was probably half-timbered.

Current state

The castle has survived to this day in the form of a ruin, and its best preserved elements are two large cylindrical towers from the 13th century, fragments of the defensive walls that are in contact with them and an inner fragment of the main gatehouse. Of the remaining elements of the castle, mainly foundation parts have been preserved, reaching the highest fragments up to a few meters, for example the south wall of the northern tower. The castle is under the care of the Cadw government agency and made available for free to explore.

bibliography:

Hilling J., Cilgerran Castle, St Dogmaels Abbey, Cardiff 2000.

Kenyon J., The medieval castles of Wales, Cardiff 2010.

Lindsay E., The castles of Wales, London 1998.

Morgane G., Castles in Wales, Talybont 2008.

Salter M., The castles of South-West Wales, Malvern 1996.