History

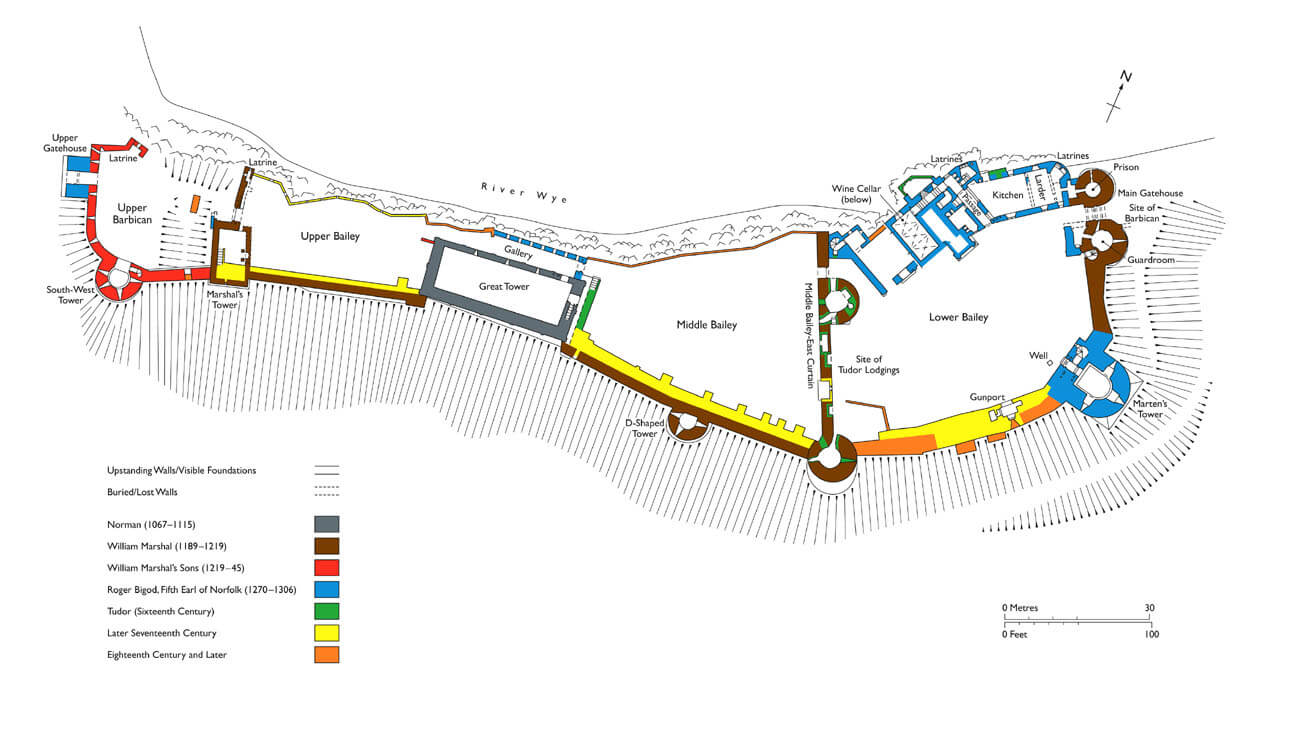

The construction of the castle began Earl of Hereford, William FitzOsbern, on the order of king William the Conqueror around 1067. The stronghold, originally called Striguil, was to secure the south-western part of the border and suppress the threat from the Welsh. FitzOsbern also built a number of other castles along the River Wye (Monmouth, Hereford), thanks to which this important route provided the Normans with total control and maneuverability throughout the region. The Great Tower – the keep of Chepstow castle, was completed until 1090, as one of the few from the very beginning built of stone, not wood. Although most of the stones were excavated from local quarries, some of the blocks were reused from the Roman ruins at Caerwent. The short rule of FitzOsbern and his son in Chepstow and the architectural elements of the Great Tower (eastern tympanum, arcades of the upper chamber) lead to the assumption that King Wilhelm himself had a greater share in its construction than the FitzOsberns. He personally visited Chepstow in 1081, while marching through South Wales to St Davids, which was a pilgrimage and show of royal strength.

William FitzOsbern died in 1071 in the battle of Cassel, and his son, Roger de Breteuil, who inherited extensive property, lost everything when he took part in the attempt to coup against king William in 1075. Chepstow, along with other FitzOsbern castles, was taken over by the Crown, until in the early twelfth century it was ruled by the de Clare family. Namely, in 1115 Walter fitz Richard de Clare received the lordship from King Henry I. Further development of the castle was associated with William Marshal, Earl of Pembroke from 1189, who, after marriage with daughter and heiress of Richard de Clare, became lord of Chepstow. William expanded and enlarged the outmodeled castle, drawing on knowledge gained in France and crusades. He fortified the central ward (middle bailey), erected the main gate on the northeastern side, and rebuilt the fortifications of the upper bailey. Further work on the expansion of the castle was undertaken by the sons of William Marshall: William, Richard, Gilbert, Walter and Anselm. In 1228, William Marshall II received 10 oaks from the king, probably for the purpose of developing the keep. After his death, three years later, another brother, Richard, did not have much opportunity to expand the castle because he quarrelled with the king and had to flee to Ireland, where he died in 1234. Gilbert regained royal favour and was gifted 50, and later another 25 oaks probably to modernize the western part of the castle. He died in 1241 due to injuries sustained during the tournament in Ware in Hertfordshire.

The male’s Marshall family line ended in 1245, and their vast estates were divided among different descendants. Chepstow passed to William’s eldest daughter, Maud, who married Hugh Bigod, the Earl of Norfolk. Their son, called Roger Bigod, took the title of Earl and ruled Chepstow until 1270. However, he preferred his estates in East Anglia and nothing indicates that he would carry out any construction works in Chepstow. Only when the goods passed into the hands of his nephew, the fifth Earl of Norfolk, also named Roger Bigod, significant investments were made in the castle. During this period, new buildings were erected at the lower ward, which served as the main residence of the Bigod family. Roger Bigod, younger, also built a new tower after 1284, later known as the “Marten’s Tower”, and rebuilt the keep, or the Great Tower, at the end of the 13th century. At the end of the work, master Reginald was to construct four ballists and pay the carpenter to build a giant crane to mount them on top of the keep.

Roger Bigod the younger, died childless in 1306, and the castle returned to the English Crown. In 1312 Chepstow received from Edward II his half brother Thomas Brotherton. From this period comes a number of documents certifying numerous repairs and supplying the castle with a garrison consisting of twelve knights and 60 footmen. Chepstow remained a royal property until 1324, when Edward II granted it to his unpopular favorite, Hugh Despenser. However, only two years later, Edward’s authority was overthrown by a successful coup d’état led by queen Isabel and Roger Mortimer. Edward II and Despenser retreated to the Chepstow castle, but did not risk a siege and escaped. Both were finally captured, Despenser was executed and the king overthrown and imprisoned.

From the fourteenth century, and especially after the end of the wars between England and Wales at the beginning of the fifteenth century, the military significance of the castle was reduced. Still in 1403, it was on the initiative of the then owner Thomas Mowbray, Earl of Norfolk, garrisoned by twenty men at arms and sixty archers in response to Owain Glyndŵr’s rebellion, but its great size and limited strategic importance contributed to the fact that it was not attacked by the Welsh. During the War of the Roses, the castle served only as a refuge for Richard Woodville, Erl Rivers and his son after the defeat at the Battle of Edgecote. Their rival, Earl of Warvick, “Kingmaker,” besieged Chepstow, but the garrison surrendered without a fight, and Woodvilles were later executed. For the rest of the 15th century, Chepstow was part of the estate granted to William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke, and in 1508 it became the property of Sir Charles Somerset, the later Earl of Worcester who rebuilt the castle in Tudor-style, into a more comfortable residence.

In the 17th century, during the English Civil War, the castle was occupied by royalist troops. They dominated in Wales at the beginning of the conflict, but in 1645 parliamentary forces under the command of Thomas Morgan besieged Chepstow. After the castle was fired, the garrison gave up. The stronghold escaped slighting, but in 1648 it was again occupied by royalists of Nicholas Kemeys. The forces of Parliament led by Oliver Cromwell again shelled the stronghold causing significant damages. The garrison gave up and Kemeys was executed. After the war, the castle was garrisoned and was maintained as a barracks and political prison. The prisoner in Chepstow was, among others, Henry Marten, one of the commissioners who signed the death sentence on king Charles I, held until his own death in 1680. In 1682, the castle became the property of duke Beaufort, the garrison was withdrawn three years later and the buildings were partially demolished, rented to tenants or left to their fate. The first repair work was undertaken at the beginning of the 20th century.

Architecture

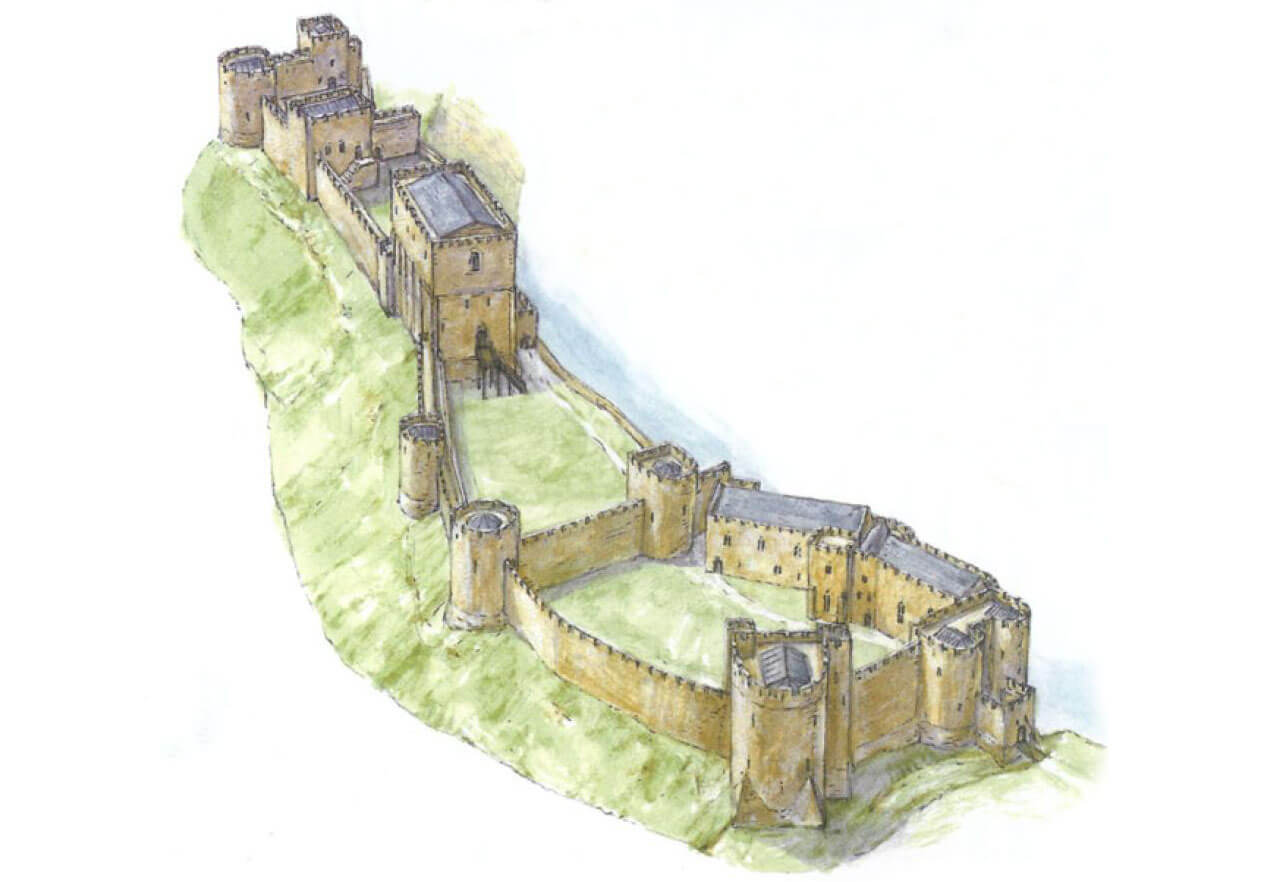

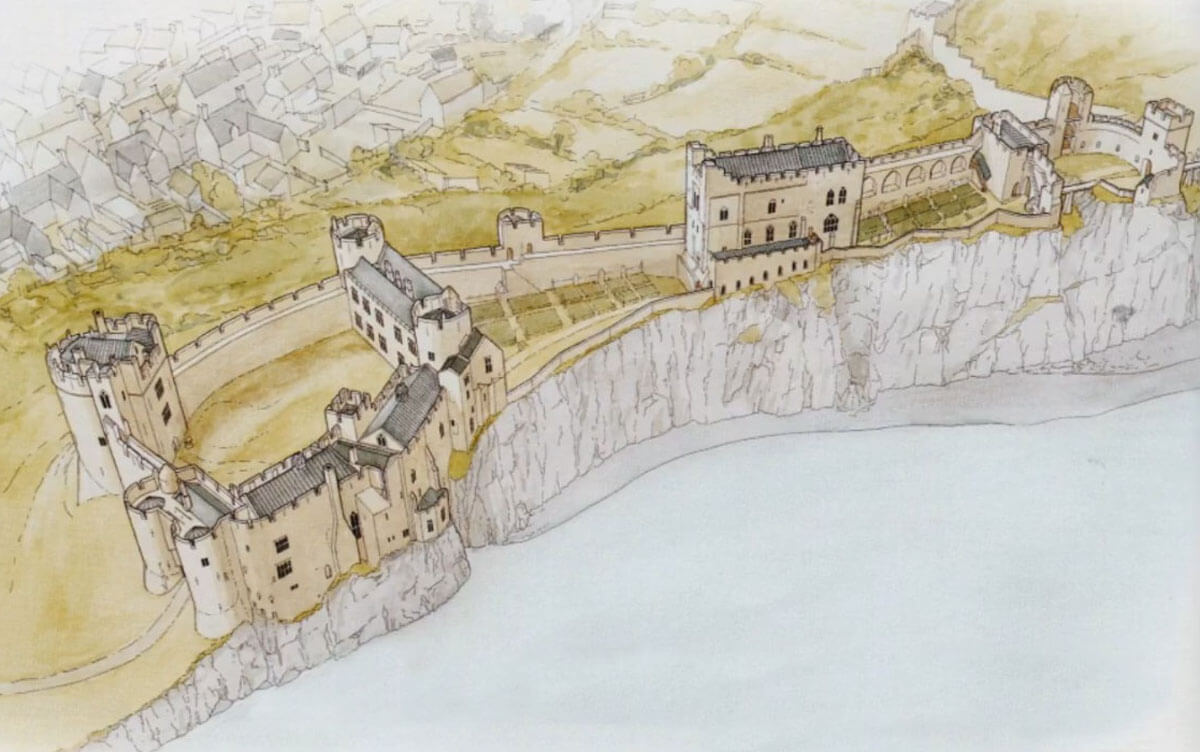

Chepstow Castle was built on a narrow, elongated ridge, between a high, steep limestone cliff above the River Wye to the north and the slopes falling into the valley of the Dell stream to the south. The area was surrounded to the east by a bend of the Wye, which flowed a few kilometres below into the wide Severn estuary. To the east, the slopes of the hill were gentler, allowing for an access road from the settlement and a crossing of the Wye. Access to the castle was also possible from the west, where it was necessary to protect the narrow neck at the end of the ridge. The first buildings were erected at the highest point of the terrain, between two ditches, probably created by widening natural rock fissures. This fenced off a well-protected area of about 85 x 20 meters.

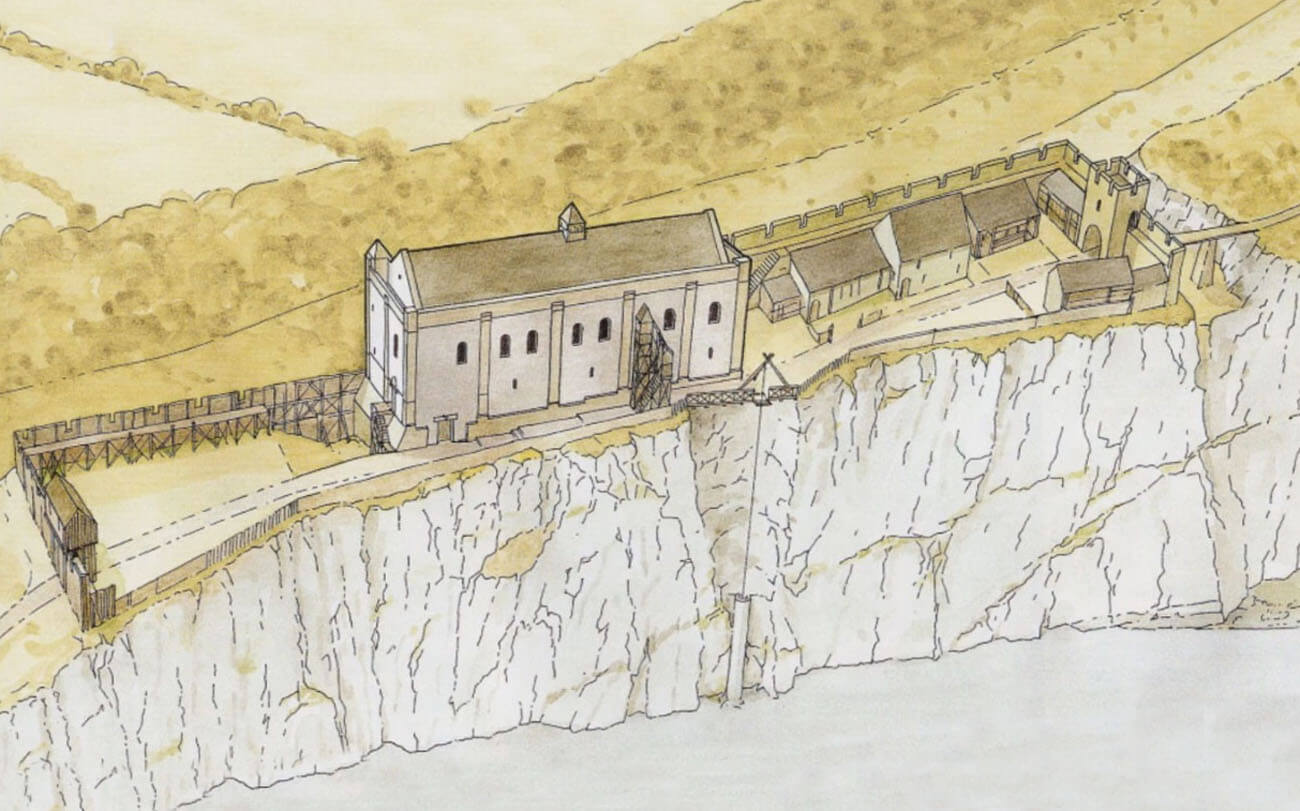

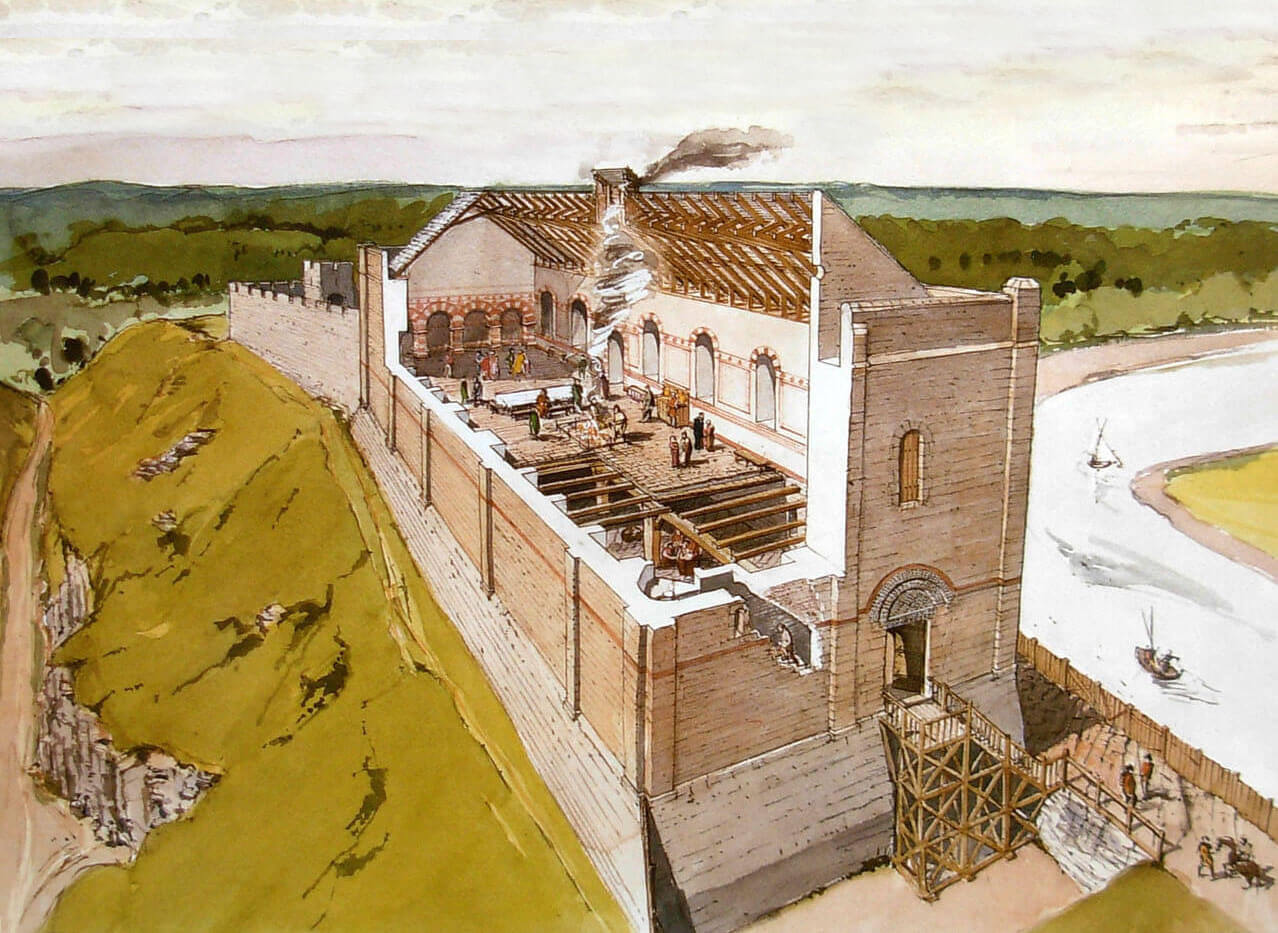

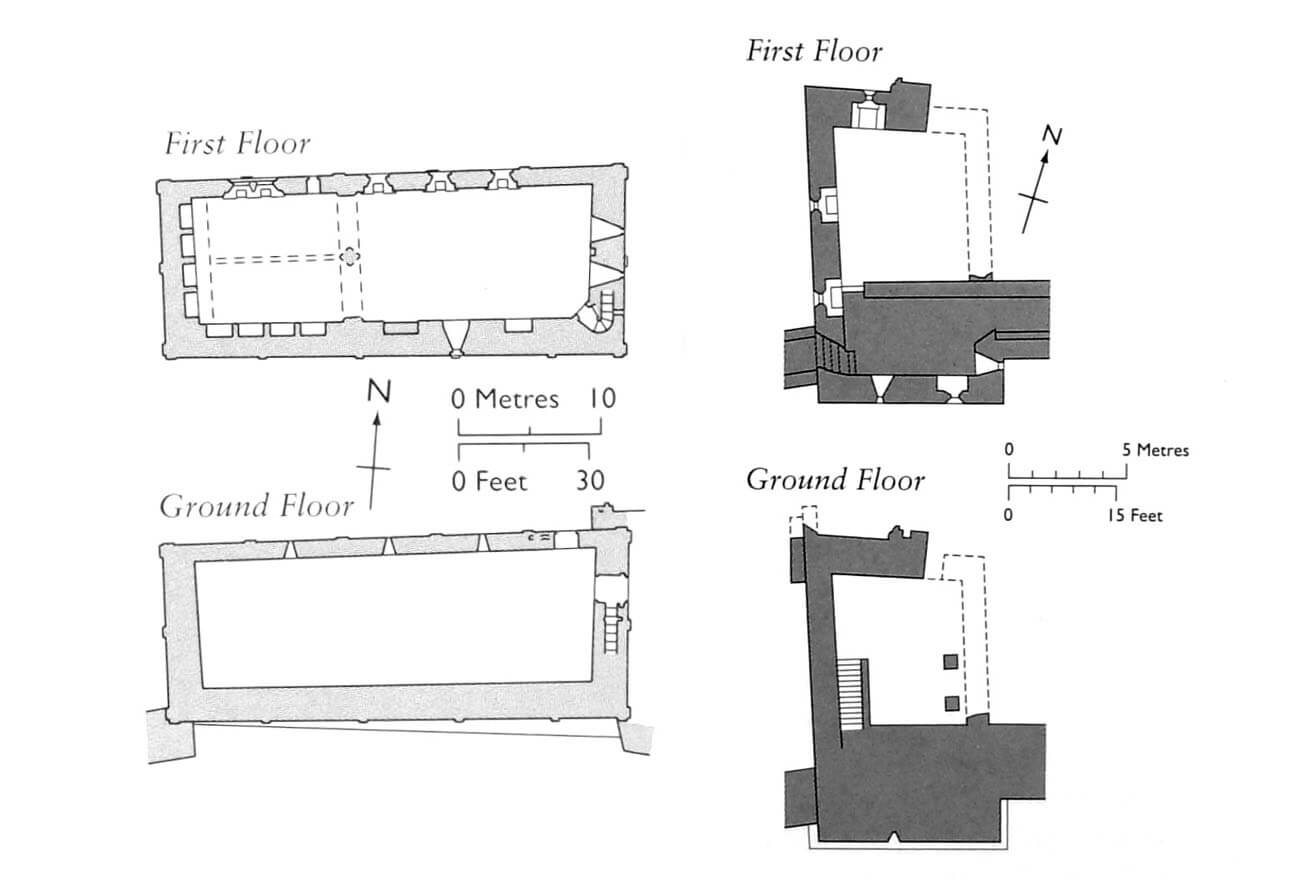

The oldest stone building in the castle was the so-called Great Tower, an elongated, rectangular building with the function of a keep, the dimensions of which were 36 x 14 meters, and the height on the western side, where the ridge was higher, originally reached about 10 meters. Due to the slope of the terrain, its eastern part was set on a massive plinth with batter. In addition, the external elevations above the plinth were reinforced with lesenes. The more endangered southern wall was more massive, about 2.6 meters thick, while the northern wall located above the escarpment was only 1.2 meters thick. In the first phase, in the 11th and 12th centuries, it was a two-level building, with the lower floor accessible from the east, through a rectangular portal with a semicircular tympanum decorated with intricately carved saltires. Access to it had to be via external wooden stairs placed over the ditch at the eastern elevation of the building. Entrances were also created from the north. One at the ground floor level, the other leading up wooden stairs to the first floor. The lower level was lit only by three small semicircular northern openings, while the upper level was lit by seven semicircular splayed windows located on the safer side facing the river. The eastern facade also had small windows, while the southern and western walls were devoid of openings for safety reasons. The defensive capabilities of the keep were limited to an unroofed gallery for guards in the crown of the walls, most likely initially devoid of battlements in favor of a simple parapet.

Originally, each storey of the keep was filled with single, spacious chambers, divided by a wooden ceiling, the transverse joists of which rested on openings in the longitudinal walls and on a single, massive beam fixed in the sockets of two shorter walls and supported from below by wooden posts. The lower floor probably originally served as a pantry and storage room, and from the 14th century as an armoury. The eastern portal opened onto a kind of vestibule in the thickness of the wall, behind which a corner spiral staircase led to the main, ceremonial chamber. This main upper hall on the southern and western sides had rows of arcades with semicircular heads in the walls, with the central southern arcade possibly being larger. It were originally plastered and decorated with white and orange patterns. The upper storey was quite unusual – it had no fireplace, latrines, division into private, smaller rooms, or passages for servants apart from the northern portal. For this reason, the upper floor was most likely not a typical great hall, but rather a representative chamber intended for holding courts, with a seat for the king in the central, largest niche on the south side.

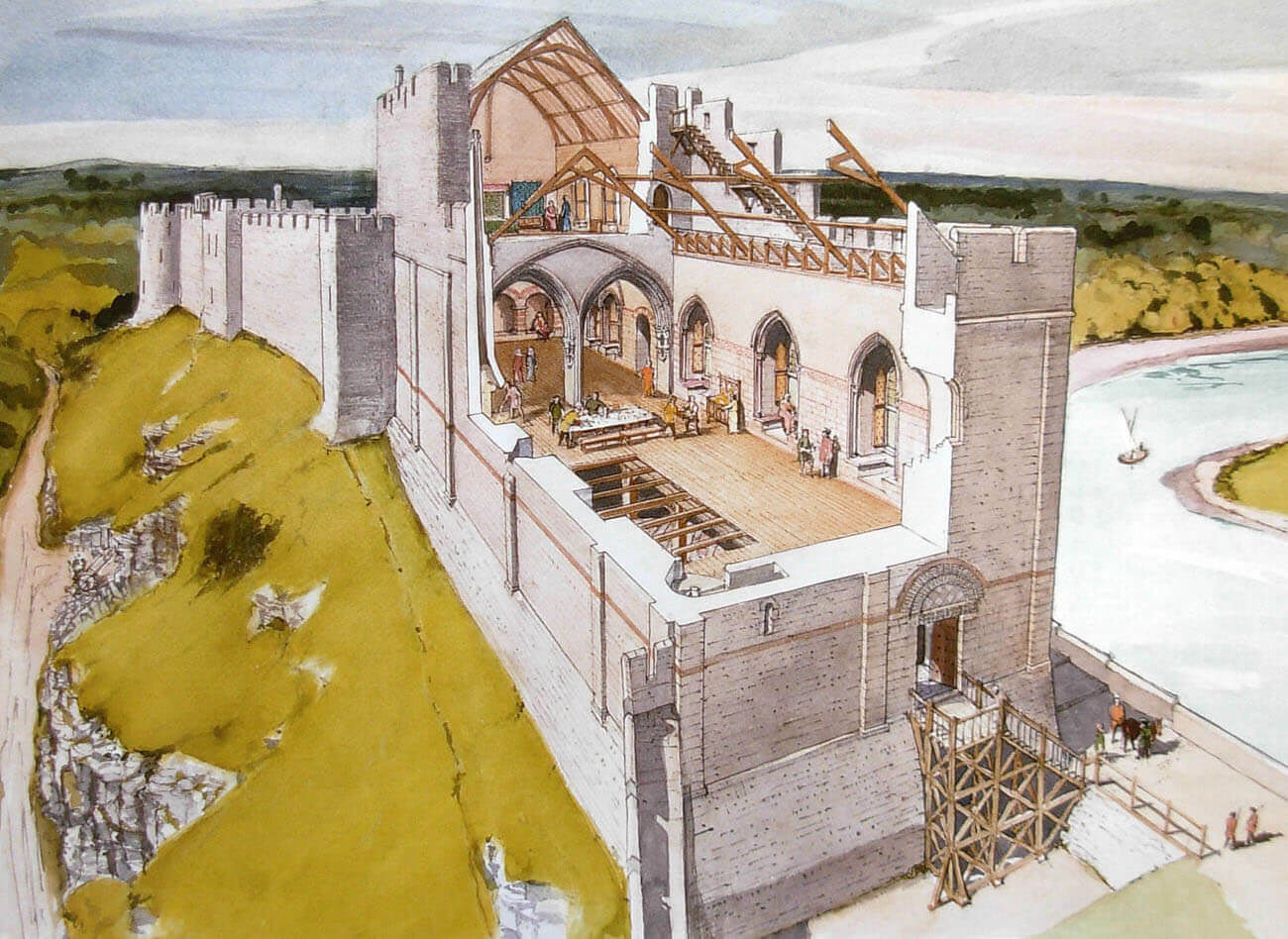

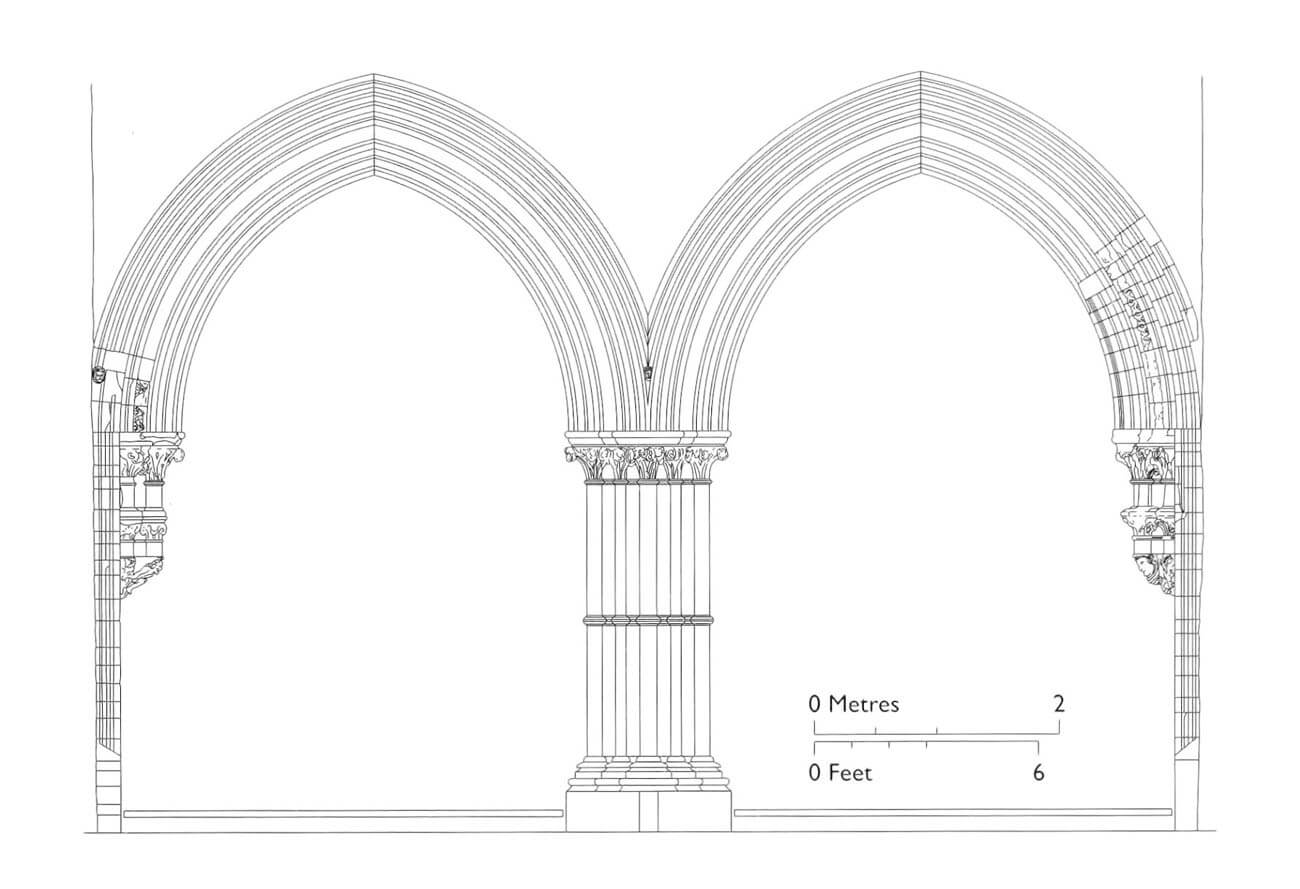

In the years 1219-1245 the upper floor of the keep was rebuilt, in the walls of which two eastern and one southern lancet windows were pierced, as well as three Gothic northern windows. The latter were set inside in deep niches, equipped with stone benches on the side facing the river. Each window was divided into two openings with a trefoil finials below the quatrefoil tracery. Only the upper part of the windows was glazed, the lower was equipped with holes for fixing wooden shutters. The most impressive two-light window was placed in the western part of the northern wall. The western part of the keep was also raised by another floor, supported on a single pillar with beautifully decorated arches springing from consoles decorated with leaf motifs and a bird or sea monster. An additional storey with a private chamber was illuminated from the north by two ogival windows and connected by means of timber, external stairs. In the former large central niche on the main floor, a fireplace was arranged, thanks to which the keep could perform more typical residential and representative functions as the seat of a lord.

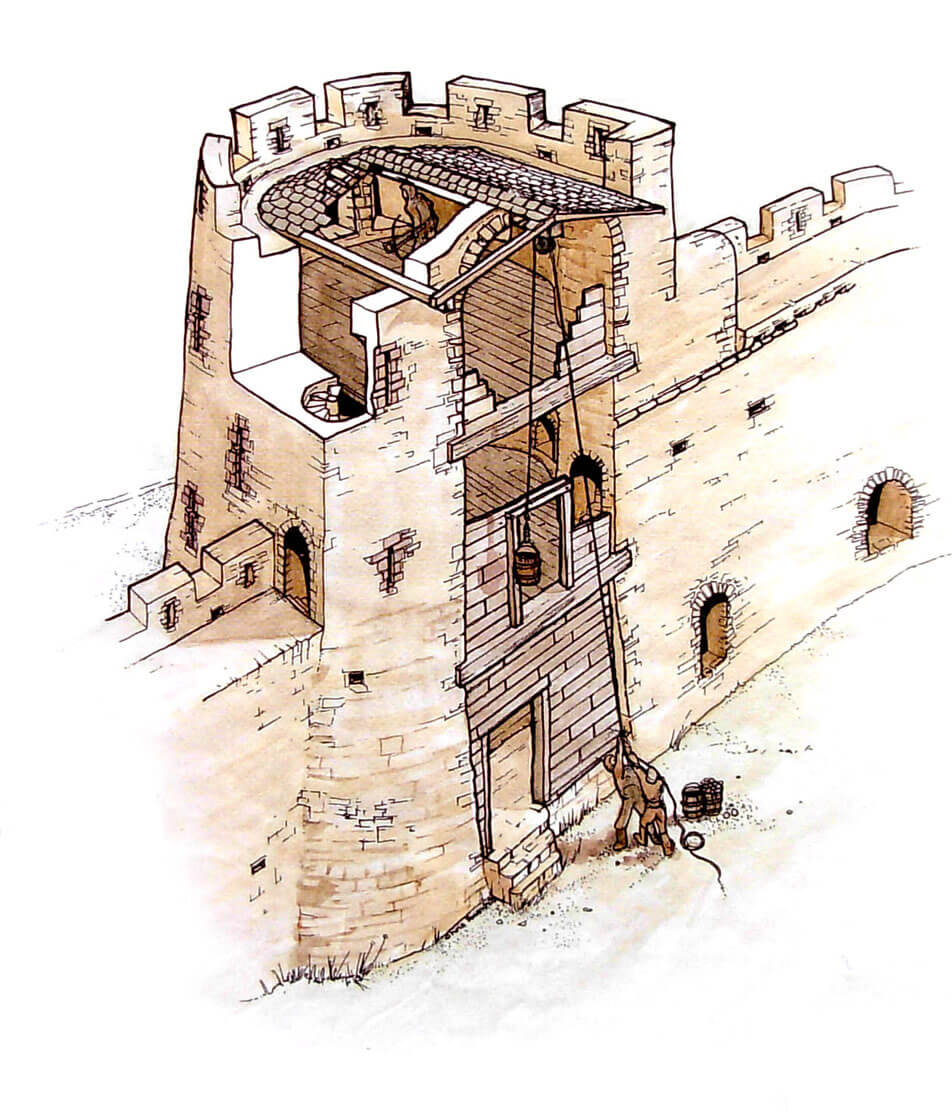

In the years 1293-1300 Roger Bigod raised the remaining eastern and central parts of the keep, placing small turrets in its corners. The entire building was covered with a common lead gable roof, around which a wall-walk was led, hidden behind a battlemented parapet. The keep then reached a height of 23 meters, remaining within the projection of the walls from the turn of the 10th and 11th centuries. On the river side, Roger founded the so-called gallery, i.e. a long covered porch running along the keep, constituting a connection between the middle and upper wards. Inside, it had a series of semicircular niches in the wall facing the river and an upper defensive wall-walk protected with battlements. Both ends: eastern and western, were closed with doors. When the porch was built, the external stairs leading from the north to the keep must have been blocked. It were probably replaced by internal staircases at that time. Below the porch, at the foot of the cliffs, a cylindrical cistern was built in the coastal mud, to hold water that would drop from a natural spring in the riverside rocks. This water was drawn by means of winches and buckets lowered on ropes.

Adjacent to the Great Tower were two outer wards: the western one, also called the upper ward (measuring approximately 38 x 16 meters), and the eastern, which later became the middle ward. Between 1189 and 1245, the middle bailey was reinforced with two towers from the east: a three-story cylindrical one in the corner and a horseshoe tower. The third, slightly smaller, protruding completely in front of the face of the wall horseshoe tower was located on the southern side. The more massive, three-story eastern horseshoe tower was also extended beyond the face of the wall and flanked the gate, pressed between the riverside cliffs on the north side, which was a mere portal pierced in the wall. In the 16th century, the interior of the ground floor of the tower was transformed into a kitchen, assembling a fireplace and a bread oven in it. The upper floors still had defensive functions and were accessible only from the crown of the defensive wall. In the Middle Ages, the middle ward was probably not built-up, performing only defensive functions. Perhaps lords also did not want to reduce the dominance of the keep over the surroundings.

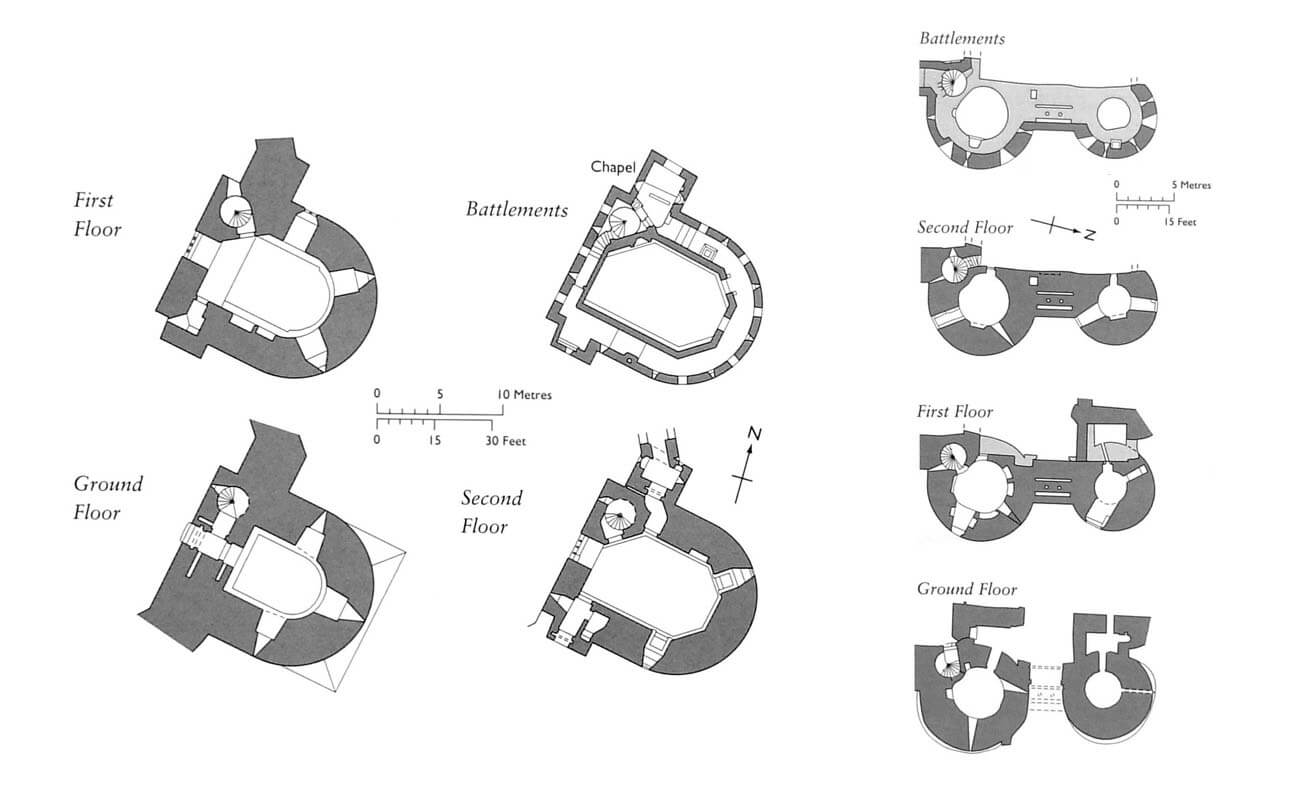

The upper bailey was the main courtyard of the 11th century castle, surrounded by two curtains of the wall with an entrance gate on the west side and protected from the north by inaccessible slopes. Around 1215, a four-sided residential tower was erected in the southwest corner, named after the founder the Marshall Tower. It housed a private chamber on the first floor and a kitchen in the ground floor. The upper chamber, known in the sources as “camera comitisse”, could have served William Marshall’s wife. It was well lit by five windows in deep niches and heated by a fireplace embedded in the wall from the courtyard side. The lower utility floor was equipped with an outflow for sewage with an outlet to the Dell Valley. In addition, on the opposite, riverside side, a latrine was placed in the defensive wall. The tower was topped with battlement and most likely hoarding, it was also was connected to the wall-walk for the defenders from the north and east. From the west, the entrance was defended by a wide ditch, cut in rock, above which a wooden bridge was erected based on a stone pillar.

In the 1230s, the western side of the castle fortifications was extended with the so-called upper barbican, a type of impressive, irregular foregate, reinforced with a horseshoe tower in the south-west corner and preceded by a new ditch. The tower was opened from the courtyard side, or, more likely, closed with a wooden screen. Wooden ceilings divided it into three storeys, between which vertical communication was provided by a spiral staircase, operating from the unlit ground floor to the upper defensive gallery protected by battlements. Each storey was equipped with four arrowslits. The barbican wall was pierced with loop holes at ground level and topped with a wall-walk, protected by a battlement with arrowslits in every other merlon. It was characterized by a wall-walk with a parapet not only on the outside but also on the inside, in case the enemy broke through the gate and could be closed in the barbican courtyard. The southern section of the wall was very massive, 2.5 meters thick, so the inner parapet could be in line with the wall face. The western section of the wall was slightly thinner, about 2 meters, so the inner parapet was set on corbels protruding from the courtyard. At the bottom of the ditch between the barbican and the upper bailey there was a small postern, probably used by defenders to leave the castle unnoticed. The northern, riverside end of the barbican wall was equipped with a latrine, similar to the one in the upper bailey, facilitating the daily life of the garrison.

Around 1298, the simple gate of the barbican was replaced by a tower protruding in front of the wall, erected on a quadrangle plan measuring 8 x 6.4 meters, despite the fact that this was already a period of rounded forms in defensive architecture (perhaps the founder wanted to refer to the gates of the royal Caernarfon Castle, also full of architectural references to older buildings). The height of the tower reached 16.2 meters from the level of the bottom of the ditch to the parapet corbels, plus an additional 2 meters for the battlement itself. Thanks to this, the difference in height of the gradually increasing terrain on the west side of the castle was balanced. The characteristic feature of the tower was its unique shape, gently curved, narrowing both on the sides and crosswise, as well as a very high arcade on the outer side, equipped with two openings in the arch for firing at attackers. Inside, the gate passage was enclosed on the sides by very thick walls and covered with a barrel vault in which two wide murder holes were pierced. From then on, it was closed with a portcullis and a drawbridge, probably operating on the principle of counterweight (the rear part was lowered down to the pit when the footbridge was raised). Above the gate passage, there was a room containing the mechanism for operating the portcullis. Above, there was another rectangular room, lit from the courtyard side by a two-light window, probably moved during the construction of the tower from the older part of the castle. The entrance to the room led only through the south-west tower and along the crown of the walls, with a few steps before the portal. The descent to the portcullis room was possible only by a ladder from the highest chamber. Both rooms above the passage were equipped with simple corner latrines, but it did not have fireplaces.

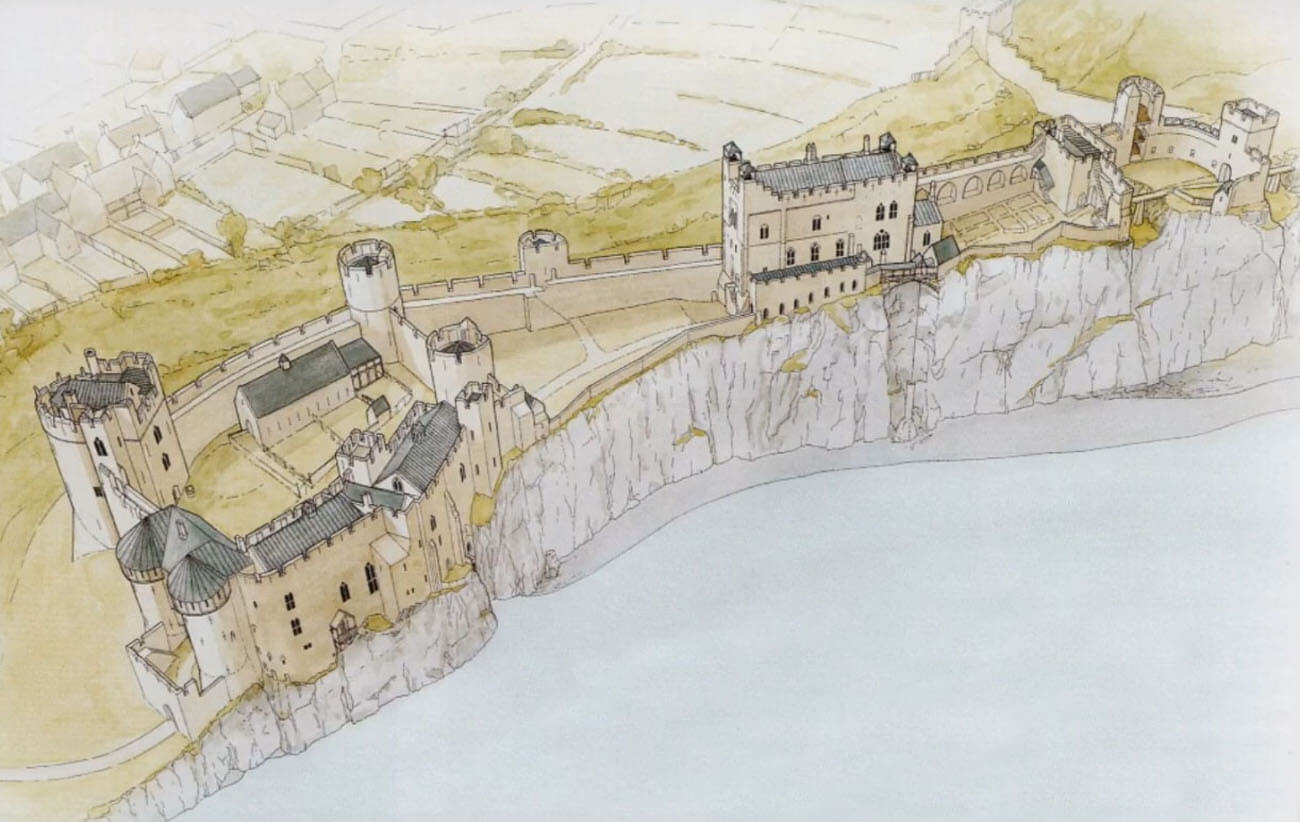

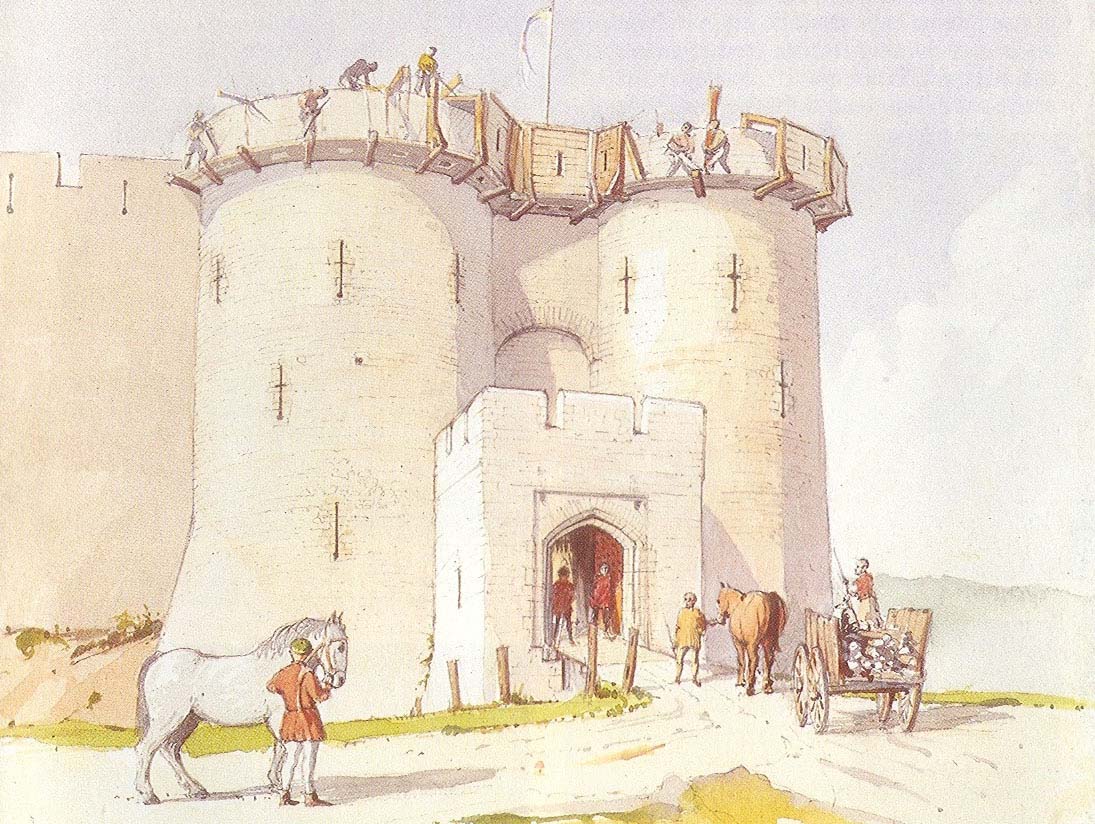

The easternmost part of the stronghold was the lower ward. Already around 1189, it received a huge gatehouse consisting of two towers flanking the passage between them. It was one of the earliest gates of this kind in Wales and England, the most modern defense system at the time of its creation. The gate passage was protected by two portcullises (whiche counterweights fell into cylindrical, carefully worked shafts), iron-studded doors, loop holes in the ceiling (the so-called murder holes), hoarding crowning the top of the gatehouse and later rectangular foregate. In addition, the lower ward was defended by a corner, eastern tower of a form unknown today. In the 13th century Roger Bigod added four-sided chambers on the inside of the gate towers, which prolonged the gate passage. In the ground floor, the left room served as a prison, while the right one served as a guards room. On the first floor, the chamber was equipped with a fireplace, so it served as a residential area, probably for the constable who managed the castle during the lord’s absence.

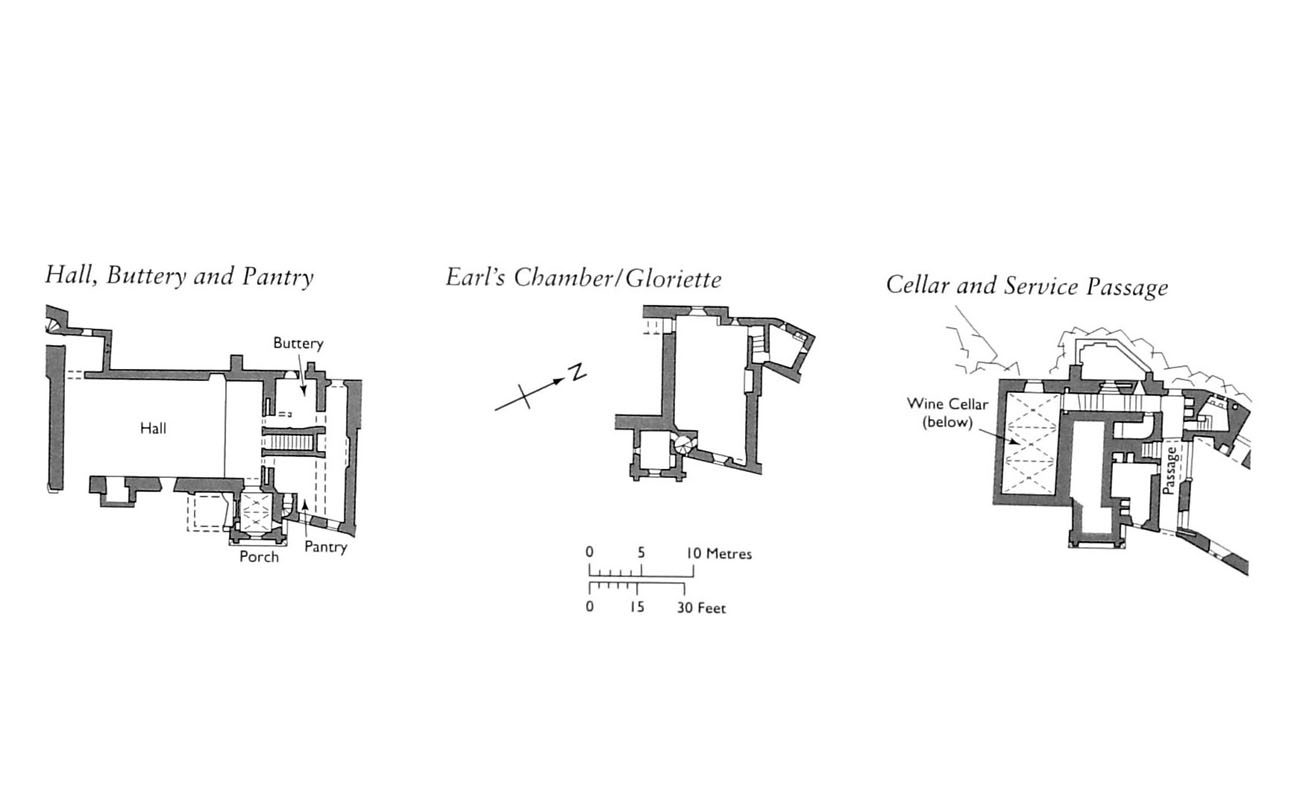

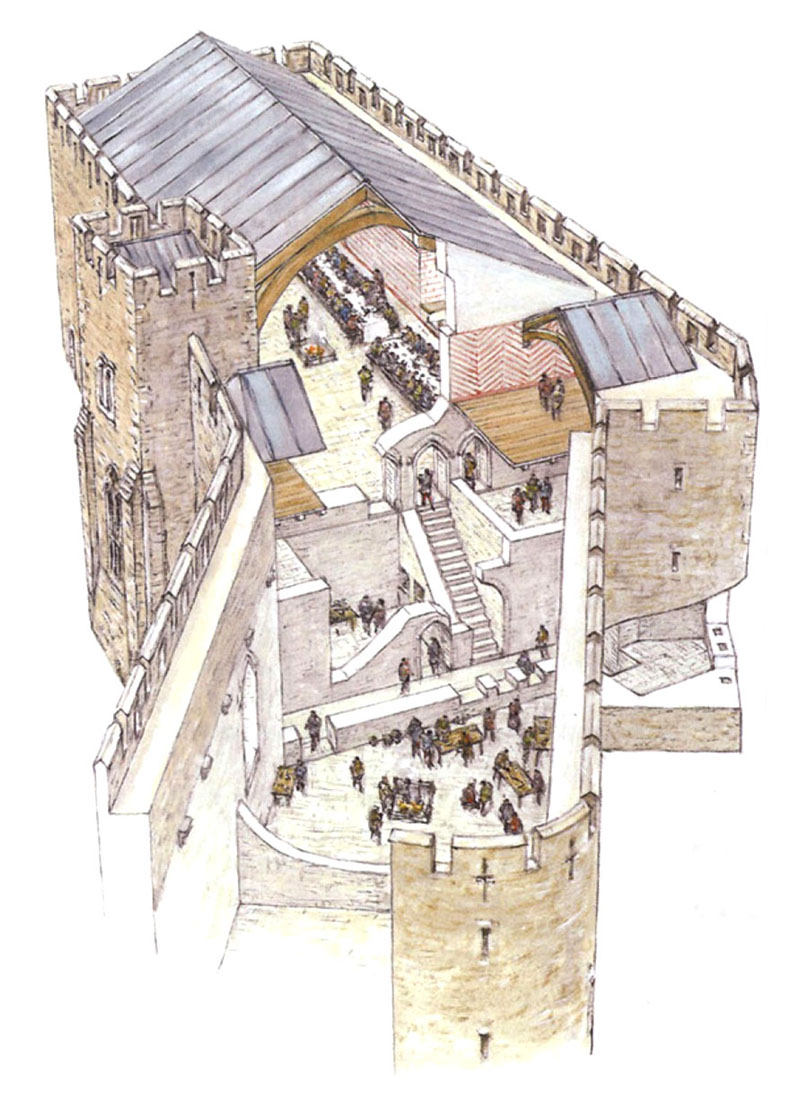

In the years 1270-1300, Roger Bigod founded a new complex of buildings in the lower ward, adjacent to the riverside, northern curtain wall. It consisted of two wings set at an angle, connected by a central passage for servants, which used the depression in the ground there. The western part of the buildings housed a great ceremonial hall, an eastern one housed kitchen and utility rooms, while between them on the first floor there were comfortable living quarters. The whole filled the space between the gate complex in the east and the transverse wall between the wards in the west, although due to its location just above the cliffs, a significant part of the lower ward still remained free of buildings (in the southern part of the courtyard, near the wall, there could have been a smaller utility building).

The great hall at the western end performed ceremonial and representative functions: guests were hosted here, meals were served and feasts were organized. The hall was 17 x 8.7 meters. Its floor was lined with decorated tiles and illuminated by large windows with rich tracery – two from the courtyard and one from the river side. At the west end of the room, there was a large table on the platform, and to the left of the podium a square room located in the turret projecting towards the river. Its upper floor could have the function of an oratory or a chapel. In the eastern wall of the great hall, three ogival portals were pierced: the left leading to the pantry, the middle leading to the stairs and the passage to the kitchen, and the right to the larger utility room. The main entrance to the great hall led from the south through a sophisticated vestibule extended towards the courtyard. Interestingly, this vestibule was preceded by a 1.3-meter deep pit, above which a drawbridge or other mechanism securing and isolating the building from the rest of the castle was placed. Inside, the vestibule was crowned with a rib vault and decorated with two shields painted on the wall above the entrance portal around 1292. Above the three portals in the eastern wall of the great hall was placed another portal, which through a timber staircase led to the private chamber of the earl on the first floor. It occupied the central part of the building complex, being a combination of a bedroom, private living room and auditorium to receive the most important guests. The heating was provided by a sophisticated fireplace. In addition to the portal to the great hall, it was also connected to the ground floor through a spiral staircase near the vestibule. Below the great hall was a wine room with three bays of the rib vault. Barrels of wine were stored here against the walls, pulled out by ropes and winches straight from the boats at the base of the cliffs.

The aforementioned central passage for the service had a height of two floors and a solid gate with bar closed it from the courtyard side. In the eastern wall three openings were pierced for serving dishes and meals from the kitchen, which were then moved to the great hall. Next to them, a small room accessible by stairs contained a series of latrines with outlets directed to the river. Opposite the stairs led to the basement and to the external terrace located on the riverside embankment, flanked by two buttresses of the upper private chambers. Originally, this terrace could have been fenced, and judging by the architectural details, it was not intended for servants, but for castle owners, giving a magnificent view of the Wye Valley.

The north-eastern part of the building complex was occupied by a spacious kitchen built since 1282 with three beautiful, large, gothic windows. Its size testified to the hospitality and splendor that the then master of the castle wanted to have. The irregular interior was topped with a high open truss and a lead roof. Cooking had to take place on a few open hearths in the middle of the room, and smoke escaped through a decorative, glazed ceramic louvre in the center of the roof. Meal preparation tables were arranged around the walls, from where dishes were served through the aforementioned openings in the wall and taken to feasts in the great hall. The kitchen also had an extensive waste removal system located in the floor and a portal in the north wall through which supplies could be tapped directly from boats on the river. The eastern part of the building was occupied by three chambers, each of which was equipped with a latrine. From the outside, the walls of the building were topped with a battlement, which, judging by the arrowslits in the merlons, did not only have a decorative function. The façade of the utility wing from the courtyard side has traces of corbels and beam slots to this day, supporting wooden or half-timbered porches, attached to the building at the height of the second floor. They provided direct communication between the earl’s private chamber and the kitchen, the eastern chambers, and even with the rear of the eastern gatehouse.

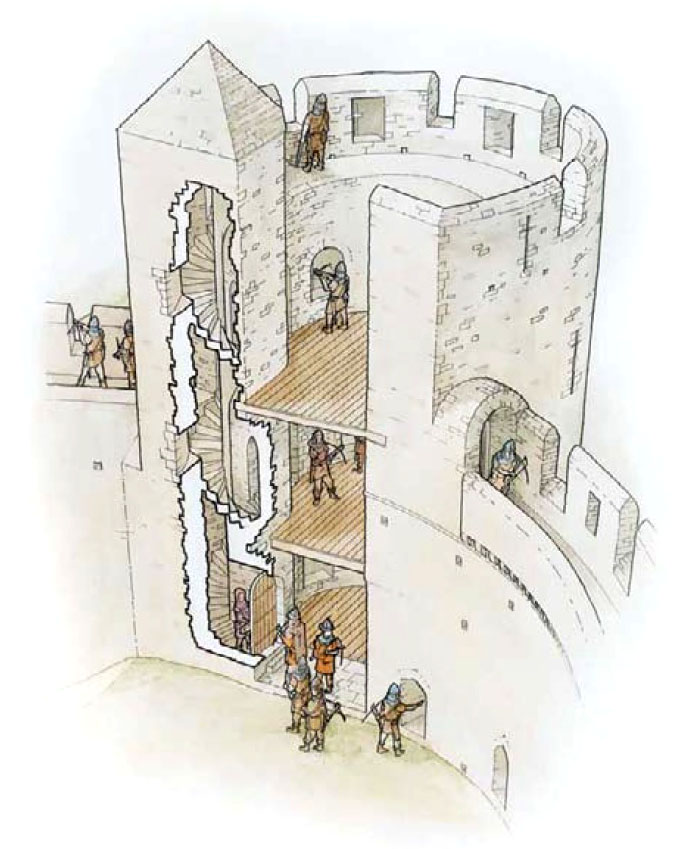

Roger Bigod’s next construction investment in the years 1286-1293 was the Marten’s Tower, a massive horseshoe tower measuring 16.4 x 13.5 meters. It was erected in the eastern corner of the lower ward, probably in the place of an earlier, smaller tower. On three floors it housed private chambers, possibly intended to host the king in the event of his visit. In addition, it was equipped with an unlit basement, a defensive gallery and an additional room in the upper attic and a chapel located in a four-sided projection at the wall on the north side. All three entrances to the Marten’s Tower (one in the ground floor and two leading to the crown of the defensive wall) were equipped with portcullises, so it could be an independent defensive work. Unusual when one of the portculiss was raised, access to the altar in the chapel was blocked. However, it had to be light enough, that it was lifted by hand, because no space was found for the winch operating it. At the ground floor there were only three arrowslits directed to different parts of the world. The chambers on the first and second floor were slightly better lit, initially with narrow slotted and pointed windows, on the second floor flanked by seats in the niches. Large windows with rectangular frames are 16th-century additions. The floors also have access to latrines and fireplaces, while the one on the first floor is an addition from the Tudor times. The floors were separated by timber ceilings arranged on the wall offset that surrounded the entire inner space. Communication between them was provided by a round, stone staircase located in the corner of the tower (except for the basement accessible through a hatch in the floor). From the outside, the Marten’s Tower was reinforced with spur and its culmination was a battlement, on which five figures welcoming arriving at the castle were placed. They depicted, inter alia, a warrior with a shield, musician and a knight.

Current state

Chepstow Castle is one of the most famous and best preserved castles in Wales and one of the most diverse and interesting in terms of architecture. It is also one of the best known, thanks to many years of research. Its uniqueness is also evidenced by one of the oldest stone donjons in Great Britain, the innovative complex of the main eastern gate at the time of its construction and the monumental complex of utility and residential rooms from the end of the 13th century. In each of these elements, numerous original architectural details have survived in the form of portals, window jambs, loop holes, cornices, pilaster strips, arcades, vaults, corbels and many others, covering the period from Romanesque to late Gothic and Tudor times. What’s more, the castle has preserved in excellent condition a unique monument – the oak, nails and sheet studded metal door of the main gate from the end of the 12th century, considered the oldest monument of this type in Europe.

The castle is currently open to the public for a fee: March to June 9:30 AM to 5:00 PM, June to September 9:30 AM to 6:00 PM, September and October 9:30 AM to 5:00 PM, and November to February 10:00 AM to 4:00 PM, with last admission half an hour before closing time. Since 1984, the castle has been under the care of Cadw, the Welsh government agency responsible for protecting, preserving and promoting the heritage of Wales. It often hosts special events and outdoor activities.

bibliography:

Gravett C., English Castles 1200-1300, Oxford 2009.

Guy N., Chepstow Castle – West (Barbican) Gatetower, „The Castle Studies Group”, No. 35/2021.

Kenyon J., The medieval castles of Wales, Cardiff 2010.

Lindsay E., The castles of Wales, London 1998.

Salter M., The castles of Gwent, Glamorgan & Gower, Malvern 2002.

Turner R., Chepstow Castle, Cardiff 2007.