History

The first castle on the hill near the Cennen River was built in the second half of the 12th century on the initiative of the Welsh prince of Deheubarth, Rhys ap Gruffudd. In 1248, his grand-daughter, Matilda (Maud) de Braose, allegedly in spite of her son, granted the castle to the English Normans. However, before the English occupied the stronghold, Rhys Fychan ap Rhys Mechyll took control of it. Over the next thirty years, the castle often changed the owner due to Rhys’s conflict with uncle Maredudd, who fought for the reign of the Deheubarth kingdom.

In 1276, the Welsh-English war broke out between King Edward I and Llywelyn ap Gruffudd (Llywelyn the Last). Edward invaded Wales in 1277, and the army under the command of Payn de Chaworth captured Carreg Cennen for the English Crown. It is true that in 1282 it was temporarily taken over by Gruffudd and Llywelyn, the sons of Rhys Fychan, but this success was short-lived and royal forces quickly recaptured Carreg Cennen. After deploying the English garrison and ending the war the following year, Edward gave the castle to John Giffard in exchange for his faithful military service. John had played prominent part in the The Second Baron’s War and the skirmish near Builth in 1282, during which Llywelyn the Last was killed. Since the royal documents do not suggest any major Crown spending on Carreg Cennen, but only smaller amounts probably needed to carry out the necessary repairs, probably John or his son of the same name, at their own expense built a castle, the ruins of which are still visible today. These works had to last from the end of the 13th century to the beginning of the 14th century. Probably began after 1284, because the castle was not visited by King Edward I during the then tour of Wales.

Carreg Cennan remained the property of the Giffard family until 1322, when they lost it due to the involvement of John, the second Baron Giffard in the anti-royal conspiracy and civil war. The castle was given to the king’s favorite Hugh Despenser, and then after a change in the balance of power and execution of Hugh in 1326, often passed into the hands of various owners. In 1362 it became the property of John of Gaunt, his property, in turn, passed into the hands of his son, Henry Bolingbroke, who was crowned as Henry IV in 1399. As a result, the castle became the property of the English Crown and one of the targets of the attacks during the Welsh rebellion of Owain Glyndŵr. This uprising broke out in the fall of 1400 and by the summer of 1403 it covered most of Wales. At that time, constable John Scudamore (Skidmore) was in Carreg Cennan, managing the stronghold on behalf of the king. Despite repelling the initial assault of 800 Welsh, a several-month siege led to surrender of the castle. During the fighting it suffered quite serious damages, because the records from 1414-1421 described in detail expenditure on repairs.

During the War of the Roses, in the second half of the fifteenth century, Carreg Cennen was garrisoned by the Lancasters under the command of Gruffud ap Nicholas. In the years 1454-1455, of his initiative were carried the necessary repairs and some modernizations at the castle, including the introduction of loop holes adapted to the use of hand firearms. In 1461, after the Lancaster defeat at the Battle of Mortimer’s Cross, Gruffudd’s sons, Thomas and Owain, took refuge in the castle, along with a large group of supporters. The following year, however, they decided to surrender to York forces, and therefore an army under the command of Richard Herbert and Roger Vaughan was sent to Carreg Cennen to take the oath of loyality. After the York capture, due to the status of a strong stronghold, but located on the sidelines, the decision was made to demolish the castle. Using of about five hundred men for four months, work was done on its destruction to prevent enemies from re-capture of Carreg Cennen. From that moment the castle has remained in ruins.

Architecture

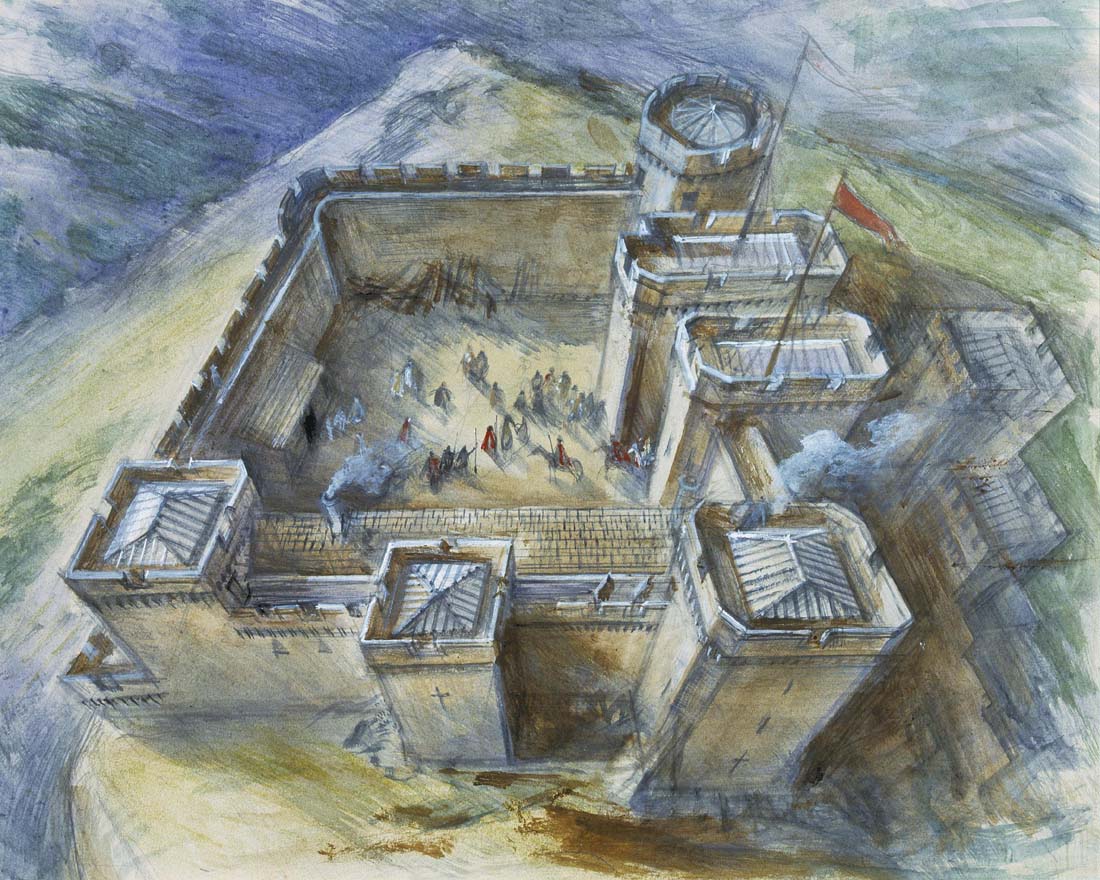

The castle from the end of the 13th – beginning of the 14th century consisted of a fortified outer ward and the upper ward, located on the top of the hill, incorporated into the limestone rocks. It was created on a plan similar to a square measuring approximately 32 x 28 meters with the southern curtain slightly bent. From the south and west, and partly north it was protected by a steep edges of the hill, while the eastern and half of the north curtain were protected by the outer ward. The nearly vertical slopes on the south side, about 85 meters high and sloping down into the Cennen River, were particularly inaccessible. For this reason, thicker walls, up to 2.8 meters wide, were created on the most endangered sides: the eastern and northern ones, while the western and southern curtains were slightly thinner. The north-west corner of the castle was reinforced with a cylindrical tower, the north-east corner with a polygonal tower, and the south-east corner with a small four-sided tower. In the middle of the eastern curtain a smaller four-sided tower was erected in which the chapel was placed. Probably all the wall curtains and towers were topped with a parapet with battlement, mounted on the corbels protruding from the face of the walls in order to widen the crown of the walls and place wall-walks for defenders on them. So it was then a fairly modern building, whose defense was based on defensive walls reinforced with towers with a strong double-tower gatehouse and favorable terrain conditions, and not on a centrally located keep.

The north-west tower was the only tower in Carreg Cennen to have a cylindrical form, about 8 meters in diameter. Perhaps it was not related to the castle’s defenses, but only to the conditions of the terrain. In the ground floor room, three cross-shaped arrowslits were placed, directed in three different directions, one of them in the 15th century was transformed into a round one, adapted for muskets. Above there were at least one, and probably two floors, accessible only from the level of the defensive walls. The western, adjacent to the tower and southern curtain, were much thinner than the eastern and northern one because of the inaccessible slopes protecting the castle in those directions. Despite this, it received arrowslits and battlement, although the defensive wall-walk had to be installed on a wooden porch. Access to it probably led from the courtyard using ladders. In the south-west corner, the defensive wall received a slight rounding, which filled the edge of the rock and prevented the need to build a tower there. Towering over the river valley, the southern curtain was equipped with two latrines and two larger openings of unknown purpose.

The north-east tower, having sides of approximately 9 meters, was the largest defensive structure in the castle, extended almost entirely outside the defensive perimeter. It was also used for residential purposes. Its corners were cut, and in the lower parts reinforced with spurs – buttresses. In it ground floor there was a fireplace and a latrine, separated from the first floor by a stone vault. The only access to the lower room of the tower led through the stairs and passage in the thickness of the defensive wall from the main hall of the east wing. The upper floor, which was also equipped with a latrine, was open to the wall-walk in the crown of the wall from the main gatehouse. For this reason, it can be assumed that it was intended for the garrison rather than household.

In the middle of the eastern curtain, a smaller four-sided tower protruded from the face of the wall. Inside, a small vaulted room is identified by the remains of a stone altar as a chapel (similarly the chapel was placed at Kidwelly Castle). It was at the height of the second floor, below which there was no room in the tower. It was probably originally planned, however, to create a chamber there at the height of the hall, because on the outside of the tower there is a latrine chute not connected with anything.

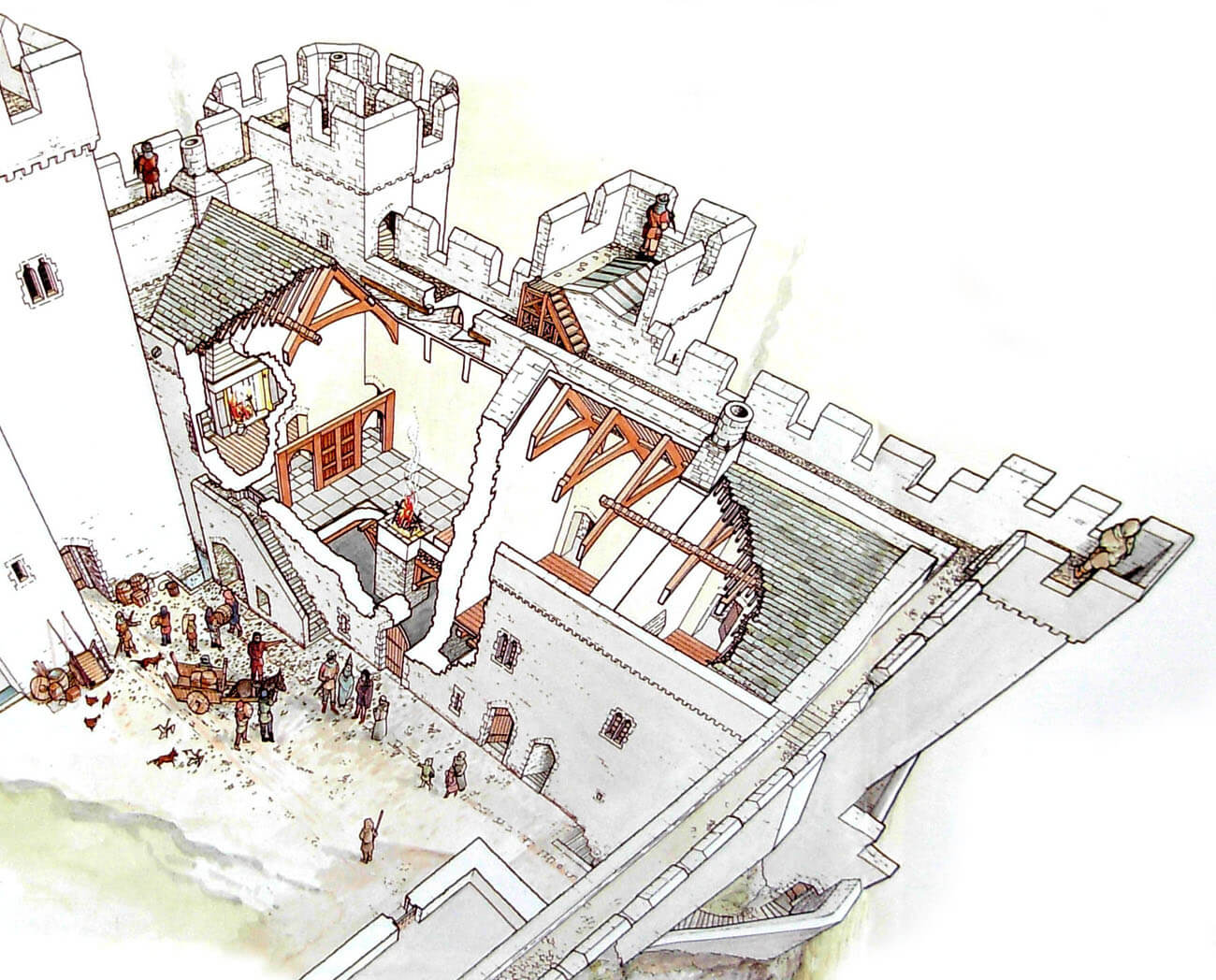

The main economic and residential wing was adjacent to the inner wall of the eastern curtain, the smaller building of unknown purpose and uncertain date was also attached to the southern curtain. On the courtyard, there were originally bread ovens in the western corner of the gatehouse and two limestone tanks for rainwater that flowed down to them from the roofs. The eastern wing housed two floors with a typical medieval layout of the utility and storage rooms in the ground floor and residential and representative rooms on the first floor. From the north on the first floor there was a kitchen, accessible through the external stairs, the hall and two private chambers. There was a small room under the kitchen, perhaps a pantry, accessible from above through a hatch in the ceiling and through the courtyard door. In the kitchen itself a large fireplace was placed, on the sides of which stone cupboards were formed in the wall. Portal led from the kitchen directly to the hall, which, however, was separated by a wooden screen, separating a kind of entrance room. Hall was the most important room in the castle, intended for ceremonies, feasts and meeting guests. On its southern side there was probably a dais for the castle lord and his family, while in the middle there was a stone, massive pillar supporting the ceiling of the basement. It was also used to light the hearth on it. What is unusual, the wooden ceiling was covered with stone slabs from the side of the hall, and the whole was supported by brackets by the walls and by the central pillar. The chamber to the south of the hall was originally connected to it, but after some time this portal was walled up, and a new connection with the ground floor room began to operate with the help of internal stairs. The lower room had stone benches by two walls with small niches below. Its purpose is unknown. The main private chamber called the King’s Chamber was on the first floor in the southeast corner of the castle. The only entrance to it led through the passage in the wall directly from the hall. It was a spacious room, well-lit from the courtyard and the southern valley side, warmed by a fireplace. The portal in the south-west corner led to a small room located in the thickness of the wall of the buttress. Originally, the buttress passed into a small watchtower, which existence is confirmed by the records of 1369 (“the tower above the king’s chamber”). At its base, stairs and a narrow passage led to the southern curtain of the outer ward. It was probably a postern gate or escape gate, connected to the vaulted passage and cave under the castle.

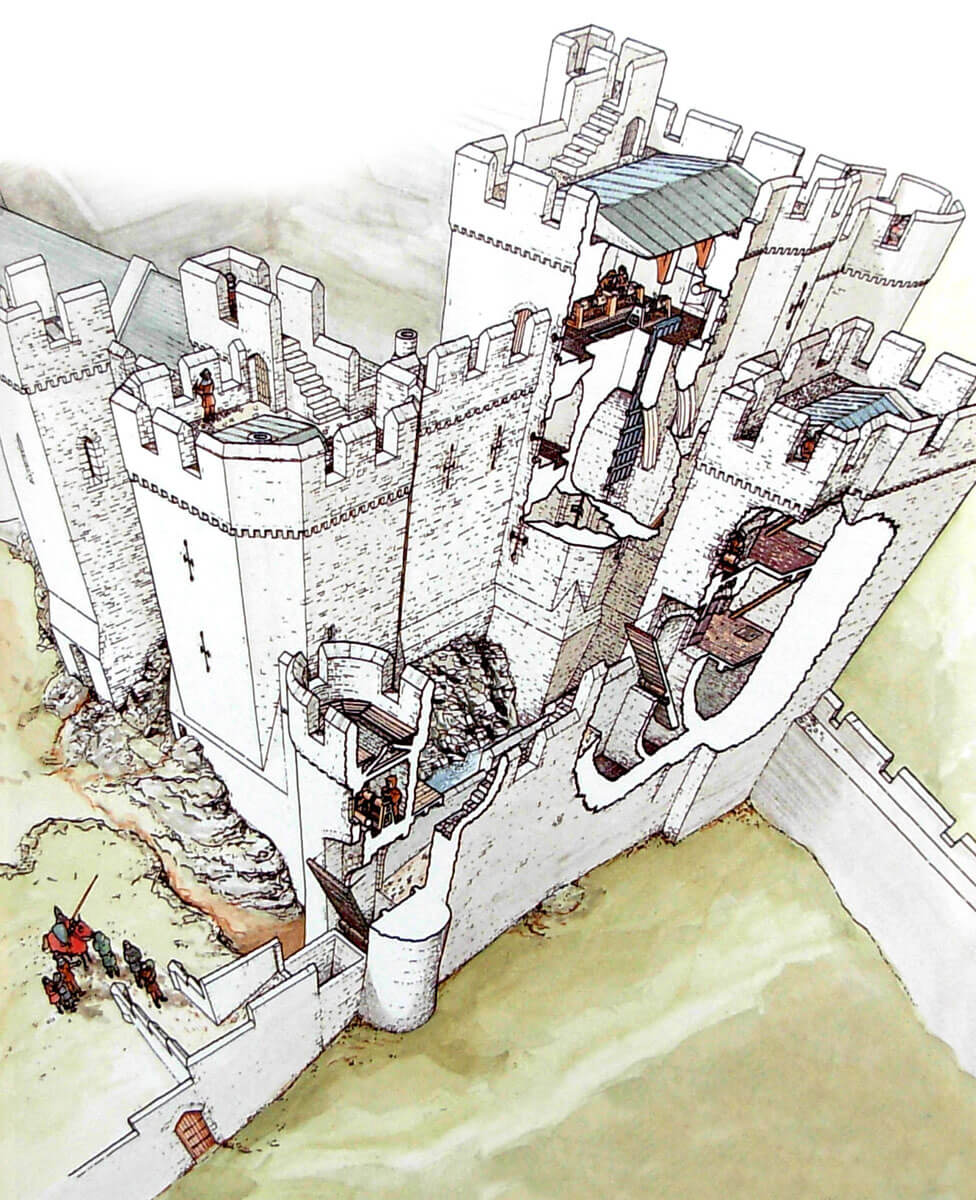

The entrance to the upper ward led through the monumental gate complex on the north side. It consisted of two three-story towers flanking the passage between them. In front of the towers, at the bend of the road was placed another, lower tower from which the foregate’s neck in the form of a stone ramp led eastwards, and then after passing another gate tower once again turned, this time to the south. Both corners were supposed to hinder the raid of potential attackers, exposing them to side fire from the upper castle. In addition, the gate complex contained three drawbridges: two on the ramp and one in front of the main gatehouse. The eastern gate tower was quite small, with rounded corners and closed with a portcullis. The next portcullis was placed in the central, four-sided gate tower in which the road turned towards the main gatehouse. It had at least two floors, the second drawbridge was controlled from the higher one and a basement located below, probably was a prison mentioned in 1369. It is worth noting that between the upper castle and the middle gate tower and ramp, a ditch was carved in the rock, closed from the east by a transverse wall to prevent the enemy from penetrating. As it was noticed that the ditch was covered with a layer of clay, it was also used as a source of rainwater. For this purpose, no latrine chute from the upper castle was directed to it.

The main gatehouse consisted of two towers in the shape of elongated halves of octagons. Their bases were reinforced with spurs or massive buttresses (similar to the spurs of the towers of the outer ward of Caerphilly Castle), while the top was probably crowned with a battlement. The walls were pierced with arrowslits in the form of crosses with a wide field of fire. The gate passage between the two towers was preceded by the above-mentioned drawbridge, lowered to two pits (when the front part of the bridge was raised, the rear hid in the inner pit, and the front pit blocked the road in front of the bridge). Additional protection were the arrowslits pierced in the side walls of the guard rooms, the portcullis and the preserved corbel, which originally could support the protruding machicolation in front of the gate. Being the main point of defense, the gate had the ability to protect also from the inside, in the event of an enemy invading elsewhere. The second portcullis and the second door from the courtyard side served this purpose. The gatehouse was also used as a living quarters, as it contained several basic living elements, such as a fireplace and latrines. The communication between the three floors was ensured by a cylindrical staircase located in the turret at the inner courtyard.

The walls of the outer ward (about 60 x 60 meters) with a wall thickness of about 1.7 meters, were erected at the latest, third stage of the castle expansion, probably at the beginning of the 14th century. Due to the terrain, they separated two courtyards adjacent to the upper part of the castle from the north and east, which protected the two most convenient approaches. Located in the east, the gate was flanked by two, small, half-round towers protruding in front of the wall. Further cylindrical towers protected each of the three corners of the outer wall of the castle, which was probably crowned with a wall-walk for defenders in the crown. A short section of the wall running out of the gate tower divided the outer ward into the northern and southern parts, another part divided the northern part of the courtyard. Their task was probably to greater control and impede the movement of any attackers. The inner buildings of the outer ward was probably made of wooden or half-timbered: stables, forge, storerooms, etc. In the southern part there was an extensive lime klin, ensuring the supply of mortar needed for construction and repair.

An interesting element was the southern part of the outer ward, which behind a defensive wall, just above the high escarpment, had a long vaulted passage leading from the south-east postern gate of the upper castle to the cave located under the castle. The passage was illuminated only by narrow slit openings from the south, and the last meters were carved directly into the rock. There, the stairs led to the cave, originally only a fissure in the rock, which after walled up was only accessible from the passage. At its entrance, holes in the wall were used as a dovecote, and then after turning north, the cave ran through a narrow and low passage for more than 46 meters. At the end of this corridor, the water flowed into a natural basin by the wall. The construction of such a long passage and connecting it to the cave is quite mysterious. Using them as a source of water and a dovecote does not seem to be the only reasons for construction. More likely, that initially the passage and the cave had also defensive functions.

Current state

The castle has survived to the present day in the form of a ruin with a legible medieval layout. The walls of the southern part of the upper ward and the eastern curtains along with the tower with a chapel and a corner north-eastern tower reach the highest height. The gate complex has been significantly degraded, but its layout remains clear, as well as the fortifications in the outer ward, where the most interesting element is the gallery in the thickness of the southern wall and the system of cave chambers. Up to a height of a dozen or so meters have survived the north-west tower of the upper ward, and the south-west corner with an arrowslit and parapet corbels. Among the buildings of the courtyard, the rooms of the south-eastern corner are visible, the southern wall of the hall has also survived. Castle is under the care of the Cadw government agency and is open daily from 9.30 to 18.30 between April and October and from 9.30 to 16.00 between November and March.

bibliography:

Davis P.R., Towers of Defiance. The Castles & Fortifications of the Princes of Wales, Talybont 2021.

Kenyon J., The medieval castles of Wales, Cardiff 2010.

Lewis J.M., Carreg Cennan Castle, Cardiff 1990.

Lindsay E., The castles of Wales, London 1998.

Salter M., The castles of South-West Wales, Malvern 1996.