History

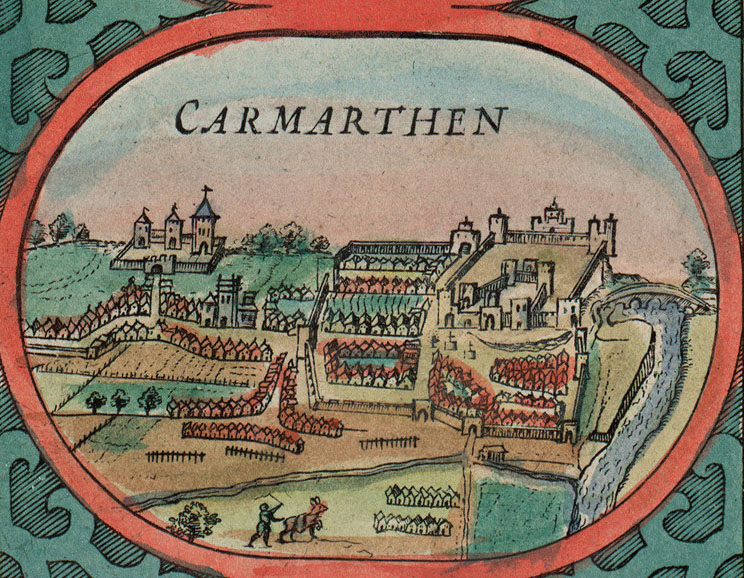

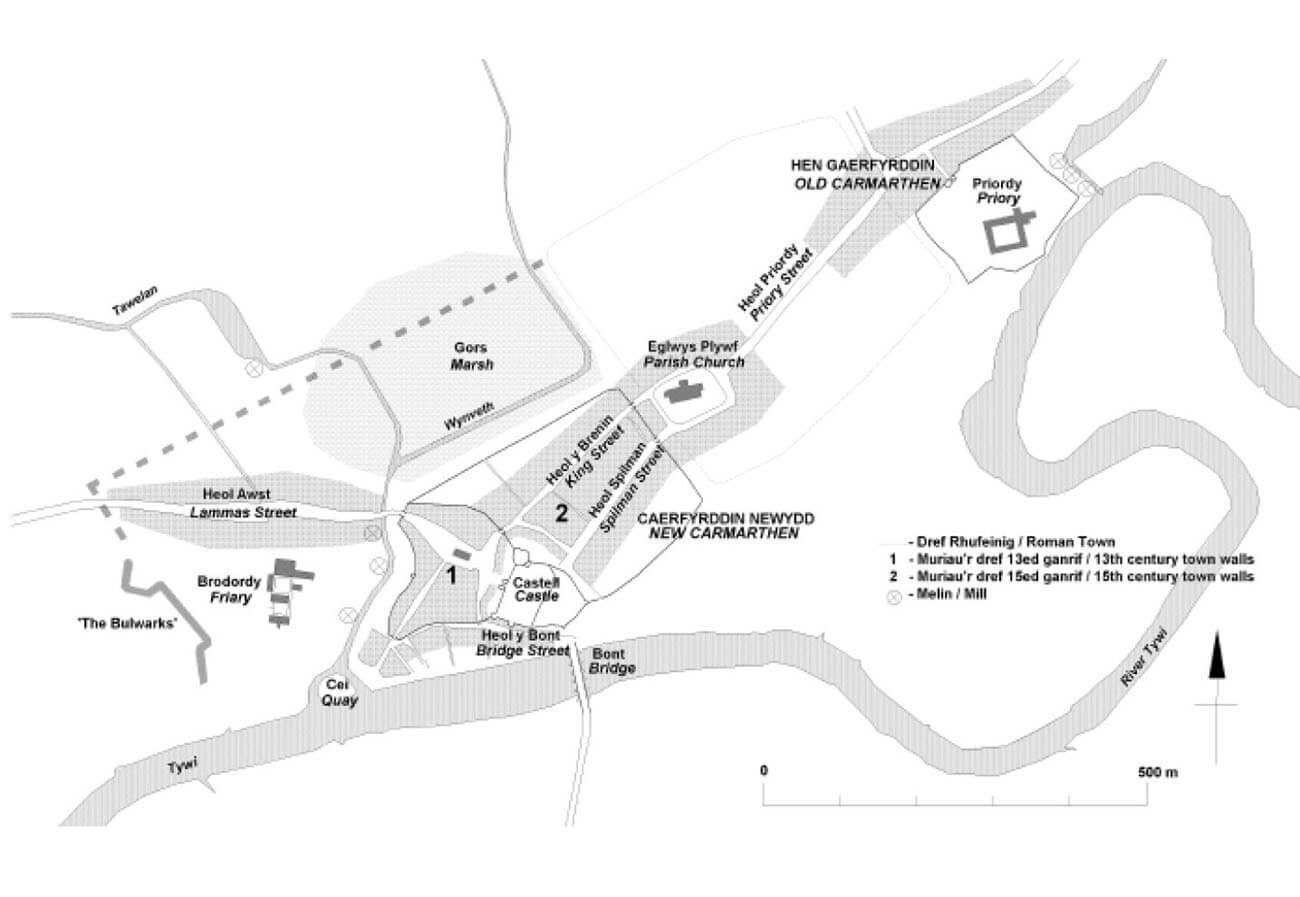

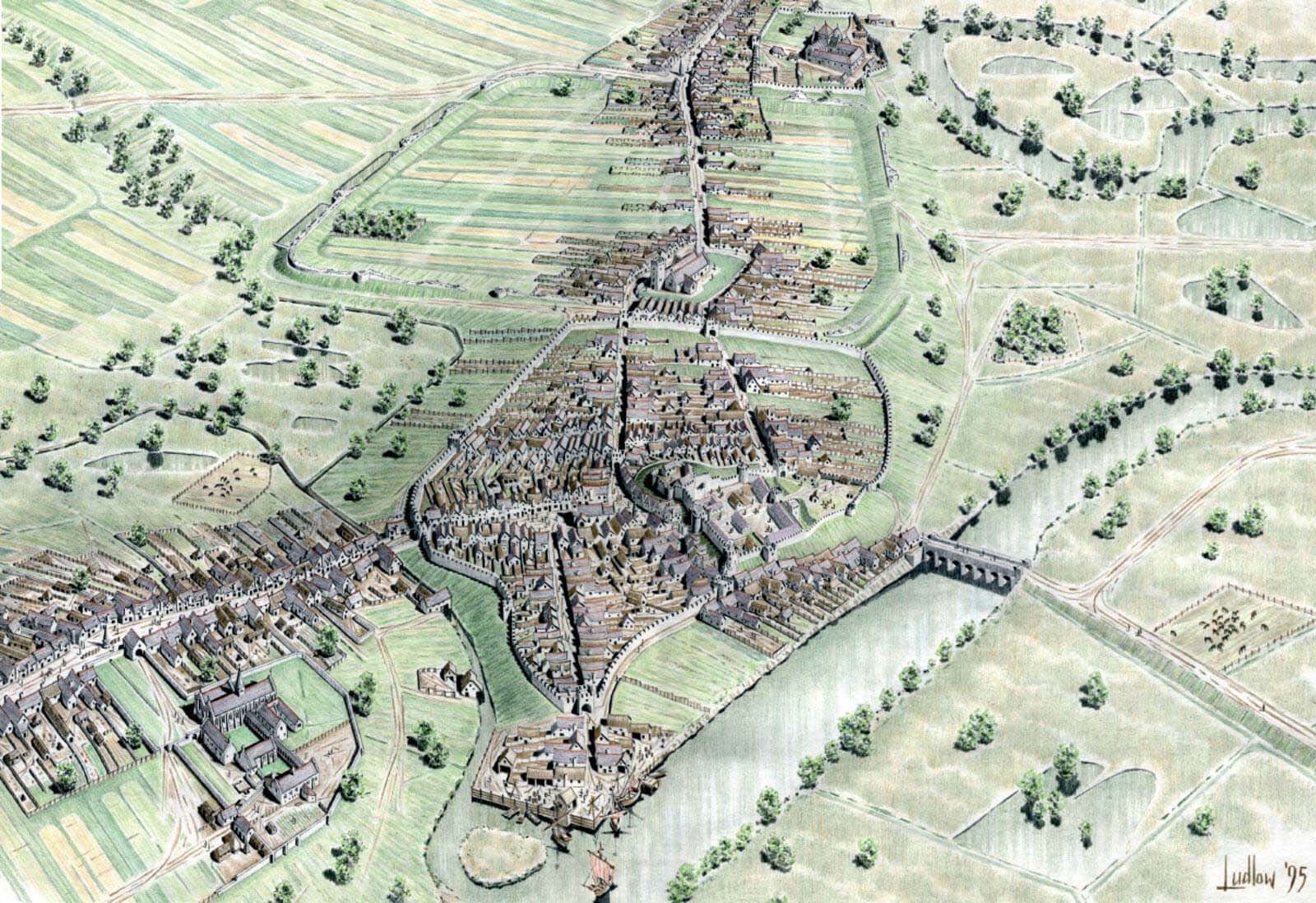

The Anglo-Norman castle in Carmarthen (Walsh: Caerfyrddin) was built in the early 12th century, near the ruins of the Roman city of Moridunum, initially as a wood and earth motte and bailey structure. It was built at the initiative of the English King Henry I, who ordered it to be built to confirm his authority over the local lords and the Welsh. It was a royal foundation established to protect and govern south-west Wales, and also to serve as a base for conquests of unconquered lands. It was situated in a strategically important place, near the crossing of the Tywi River, which was an important communication and trade route and which was navigable for large boats to this point. In 1109 Henry I was to send to Wales to defend Carmarthen the sheriff of Gloucester, Walter FitzRoger, so the castle must have been completed by then. Then, at the foot of the castle in 1116 a town was founded.

Until 1130, as a result of reorganization, the castle became the center of the local Anglo-Norman lordship occupying the former Welsh kingdoms of Ystrad Tywi and Dyfed. For most of the twelfth century, Carmarthen was the only royal center in West Wales, because Pembroke passed in 1138 to Gilbert de Clare and subsequent marcher lords, and the next royal outpost in the region only appeared with the takeover of Cardigan in 1200 by King John. For this reason, Carmarthen was exposed to repeated Welsh attacks, as one of the most frequently invaded castles in West Wales.

The first of the Welsh raids was carried out at night 1116, by the troops of Gruffudd and Rhys. They did conquer the town and the castle bailey, but the main part of the castle (motte) managed to defend itself. The temporary fall of the castle brought a period of turmoil after the death of King Henry I in 1135. Two years later, Carmarthen was captured and burned by the Prince Owain Gwynedd, remaining in Welsh hands for another 20 years. The actions of the conquerors in this period are unknown, but probably the town, and perhaps also the castle were in ruin all this time, because after temporary recovery in 1145, Gilbert de Clare, earl of Pembroke, was supposed to rebuild it. Shortly afterwards, Carmarthen returned to the Welsh of Cadell, son of Gruffudd ap Rhys, and the good condition of the fortifications meant that in 1147 the castle resisted the invasion.

In 1155 Cadell lands fell to his brother, Rhys ap Gruffudd, one of the leading figures of 12th-century Wales. He owned Carmarthen until his surrender to King Henry II in 1158, and although a year later during the anti-English rebellion he managed to occupy most of the enemy strongholds in Dyfed, Carmarthen remained in the hands of the monarch thanks to the English relief. Once again, the castle was defended in 1189 during the next rebellion of Rhys, after the death of Henry II. This time relief was brought by Prince John, the future English king. Thanks to this, at the end of the twelfth century, Carmarthen was one of the few castles of West Wales under the control of the Anglo-Normans, although in 1197 Rhys was to carry out a successful invasion and burn it. However, he probably did not take Carmarthen permanently, and the war ceased after the death of the Welsh prince in the same year.

In 1214, Carmarthen and Cardigan was handed over by King John to William Marshal I, earl of Pembroke. A year later, a great Welsh uprising broke out under the leadership of Llywelyn the Great, and after five days of fighting the castle was surrendered and again destroyed by the conquerors. It wasn’t until 1223 that Henry III sent a large army to Wales under the leadership of earl of Pembroke, William Marshal II. It recaptured the castle, and Llywelyn’s Welsh relief ended in an unresolved battle at the Carmarthen Bridge. Cardigan and Carmarthen then again became the basis of English strategy in subjugating Welsh lands, and were thus exposed to retaliatory attacks. This forced intensification of construction works on the rebuilding of the original wood and earth fortifications of the castle into stone fortifications. They proved so effective that in 1233 a royal garrison of the castle survived the siege of Richard, a rebel brother and heir of Earl Marshal, assisted by Welsh troops for three months. The crew was saved by the Bristol fleet of Henry de Turbeville.

In 1240, Llywelyn the Great, the last Welsh ruler aspiring to independent rule over all united Wales, died. Lesser local rulers took an oath of allegiance to Henry III, including Maredudd ap Rhys Grug, who governed West Wales. Since then, Carmarthen castle remained in English hands, although in 1246 Maredudd ap Rhys Grug devastated the town itself. In 1254 Henry III gave all royal property in Wales to his son Edward, later Edward I, during which further work was carried out on the stone buildings of the castle, this time primarily residential – representative. Edward I treated Carmarthen as one of his bases against Llywelyn ap Gruffudd (grandson of Llywelyn the Great), as well as one of the major political and administrative centers of the region. Carmarthen was the launching point of Edward I’s military campaigns against South Wales in 1276-77 and 1282-83, after which the whole region was reorganised on English model as Carmarthenshire.

In the late 13th century, Carmarthen took part in the suppression of the last native Welsh prince. Maredudd ap Rhys’s son, another named Rhys, was granted possession of nearby Dryslwyn Castle, but was subject to the absolute control of Robert Tibetot, the king’s deputy in Wales and the administrator of Carmarthen Castle. Starting a rebellion in 1287, Rhys attacked and “burned to the gates” Carmarthen, but failed to take the castle. In retaliation, a large force was drawn from England and Wales, which gathered at Carmarthen and then marched on Dryslwyn Castle, where Rhys was eventually captured and executed.

In the 14th century, the castle was gradually expanded, and its garrison was on standby during the rebellion of Roger Mortimer in 1321, during the threat of a French landing in 1338 and for fear of retaliation for the French war campaign of Edward III of 1359-1360. Similarly, the garrison was strengthened and feverish repairs were carried out in 1369 and 1385. In the latter case, the castle constable was supposed to have 24 crossbowmen with crossbows, 12,000 bolts and 40 lances. As a royal seat and a symbol of English domination in Wales, Carmarthen became one of the main targets during the great Welsh uprising of Owain Glyndŵr. For the first time, rebels approached the castle in 1401, but withdrew after the arrival of Henry IV’s army. Again, large forces of Glyndŵra came through the valley of the Tywi River in 1403 and after a short resistance of the then constable Roger Wigmor, they took Carmarthen. In the same year, the castle was recaptured, but the garrison was too thin, thanks to which in 1405 10,000 Welsh people assisted by 2,500 French captured Carmarthen again. Glyndŵr retained control of it until 1406, when the entire region began to move to the monarch’s side. The destroyed town and the damaged castle remained in the hands of the English until the fall of the uprising 2 years later. In subsequent years, repairs were carried out, which confirmed the still significant importance of the castle, used for residential – administrative, court and military purposes, as opposed to the decline of such centers as Caernarfon or Conwy.

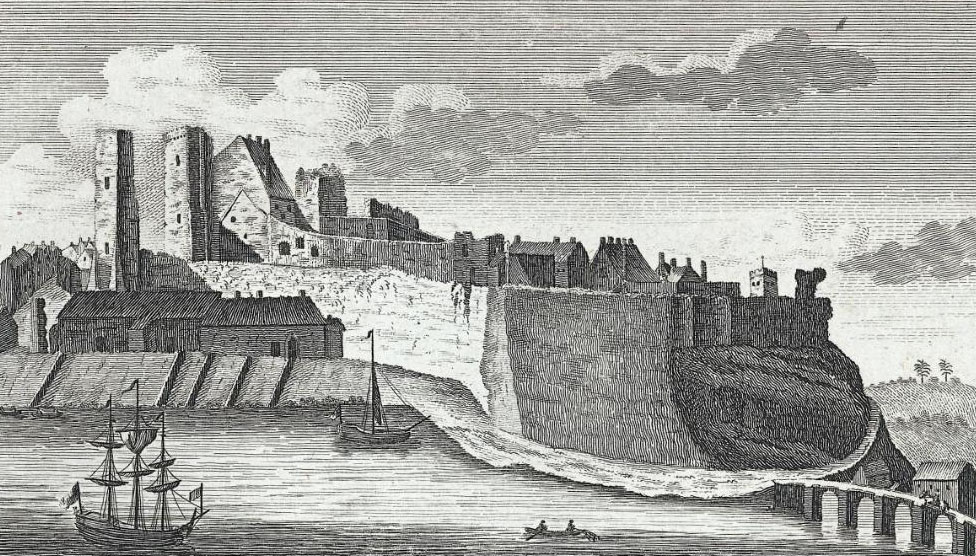

In connection with the pacification of Welsh-English hostility under the new Tudor dynasty, the 16th century passed relatively peacefully for the castle, probably it has not been significantly transformed. The collapse of the building, like many others in Britain, was associated with the outbreak of the English Civil War of the 1640s. The castle was occupied by supporters of the king, but the landing of parliamentary forces in 1644 managed to capture it. Monarchists managed to recapture it, but this did not improve their situation and eventually ended in surrender. Shortly after the war ended, due to Parliament’s fear of re-using the fortifications, demolition of the castle buildings and fortifications began, and those that survived began to be obscured by modern buildings and gave way to the one of the harshest prisons in England.

Architecture

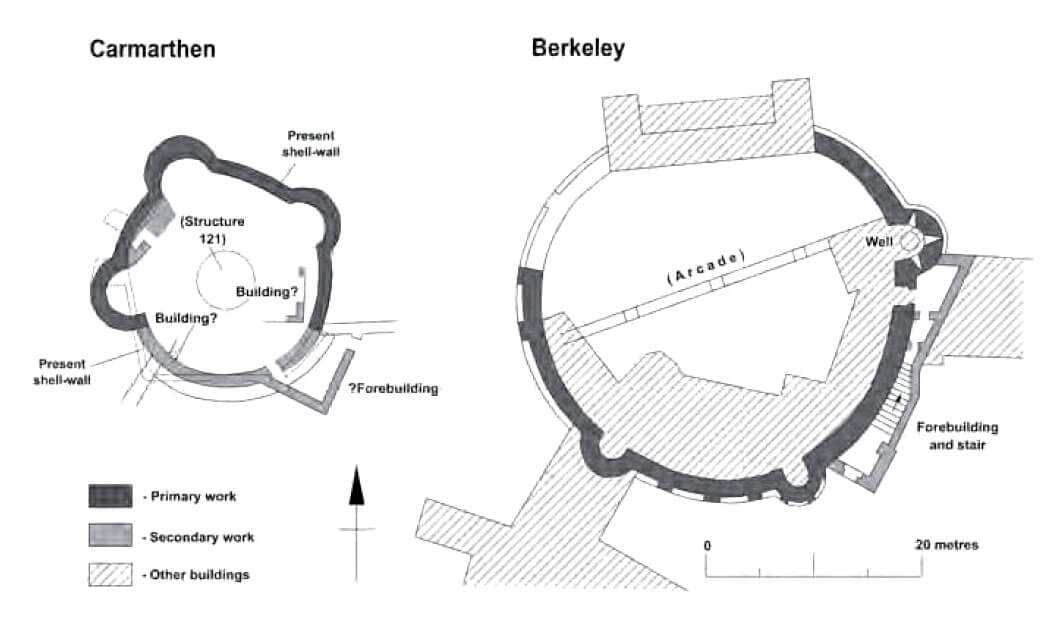

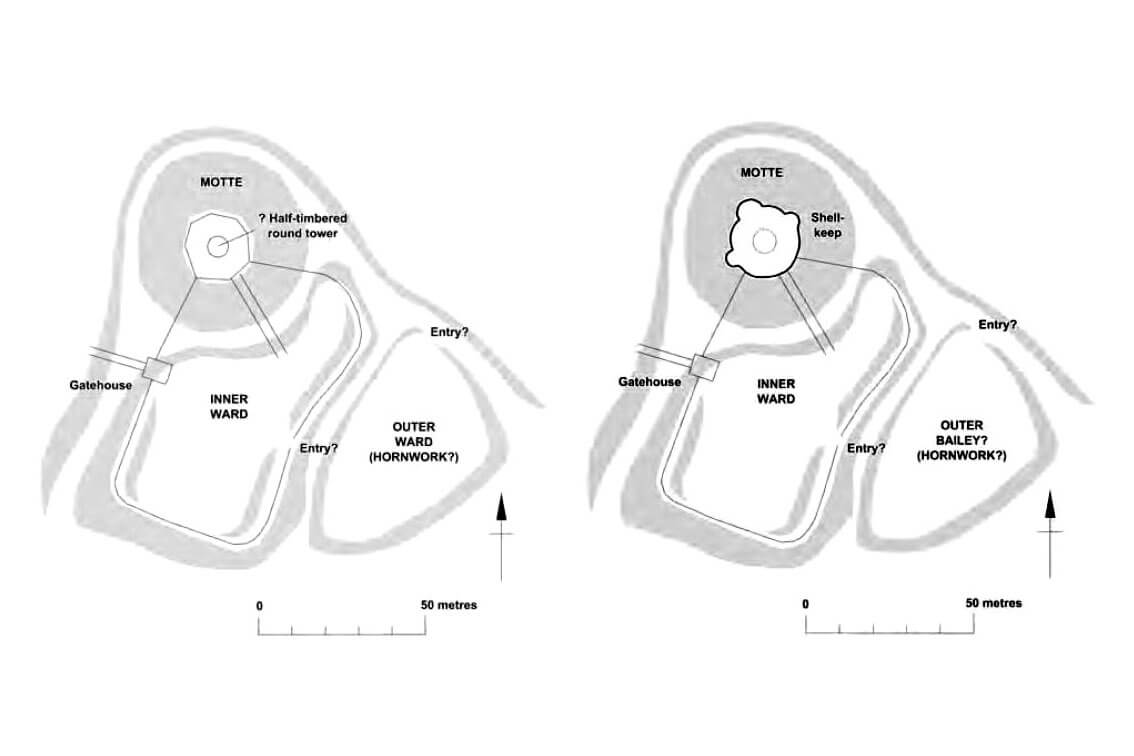

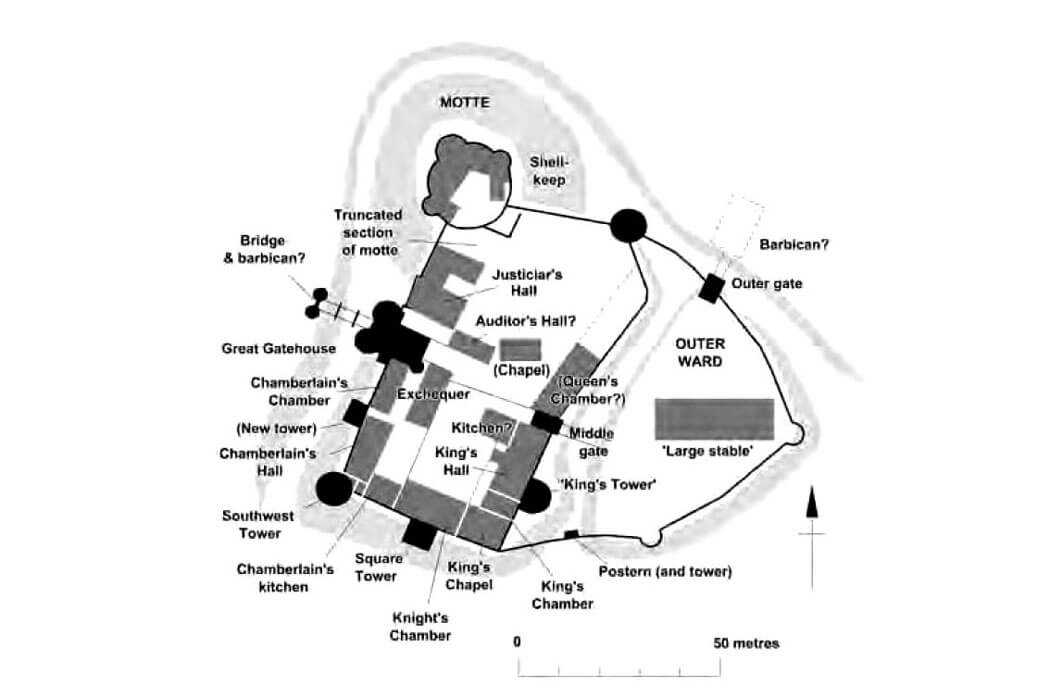

The castle was located on the northern bank of the Tywi River, characterized by high slopes, on the eastern side of the settlement and the later town of Carmarthen. Originally in the 12th century it was a motte and bailey structure, consisting of a wooden defensive perimeter built on an artificially raised earth mound, cylindrical in plan, 30 metres in diameter and conical in shape, reaching a height of about 10 metres. In the centre of the mound a cylindrical or polygonal wooden tower was built on a stone base, with an external diameter of about 5.8 metres (internal diameter 2.9 metres). The tower was rather small for permanent residential functions, probably serving more as a watchtower and final defense point. It was accessible through a wooden ramp along the slope of the mound from the south and a wooden bridge over a 15-meter wide ditch that surrounded the hill.

The castle had two outer baileys separated by a ditch: the upper (inner) one on the southern side, where mainly residential and administrative buildings were located, and the lower (outer) bailey, smaller one, south-eastern, with an economic function. In the upper bailey there could have been a hall and a chapel, recorded for the first time in the years 1158-1176. The early, 12th-century construction of the lower bailey is not so certain, and its location on the opposite side of the developing town is quite unusual. Perhaps originally there was one large bailey, later divided into two parts (similarly to the castles of Rochester or Kidwelly) or perhaps it was occupied in the early 12th century by ramparts in the foreground (hornwork), directed towards the river crossing and protecting the back of the castle.

The recorded expenditure of 170 pounds in the 80s of the 12th century probably served to erect or start construction at the top of the mound of a cylindrical circumference of stone walls (shell keep) with an internal diameter of about 16 meters, in place of earlier wooden fortifications. They did not receive a perfect circle in the plan, because the ring had three or four rounded projections (according to written sources, even five, maybe an unknown fifth was embedded in the thickness of the walls or above them), resembling half towers. They were directed in every direction except the south and south-east, and thus everywhere except for the directions facing the outer baileys. This solution was quite unusual for Wales and the closest similar shell keep was at Berkeley Castle. The entrance to the defensive perimeter on the mound was in the simple gate portal, not preceded by any gatehouse or tower. As the wall on the mound was not a tower, a number of wooden or half-timbered buildings lay against its inner elevation, surrounding a small courtyard, perhaps still occupied by a wooden tower.

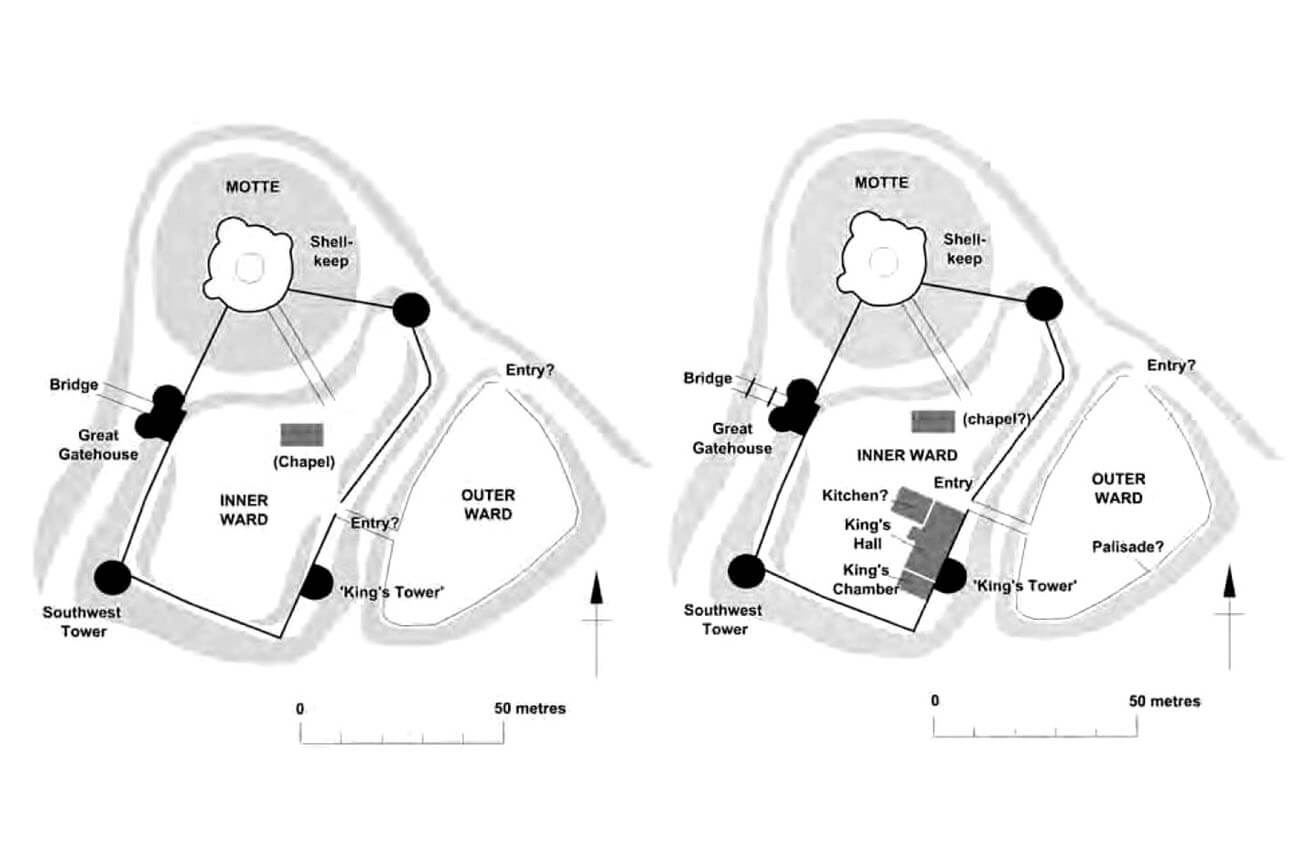

After the Anglo-Normans recapture Carmarthen in 1223, a major reconstruction and expansion of the castle was undertaken, ended around 1241 with the creation of a fully stone complex. The wall surrounding the mound was completed or rebuilt, and additional stone fortifications were built for the inner bailey, located to the south of the mound. It then began to border the town, fortified with stone walls, although it is not known whether it was directly connected. To the south, the slopes descended towards the Tywi river. To the south-east of the upper bailey, there was a river crossing, while to the south-west, on a promontory formed by the river and a stream flowing into it from the north, there may have been a suburban fishing settlement. The western part of the castle faced the main part of the town with the parish church, market square and through street. To the east there was the lower bailey, initially devoid of stone fortifications.

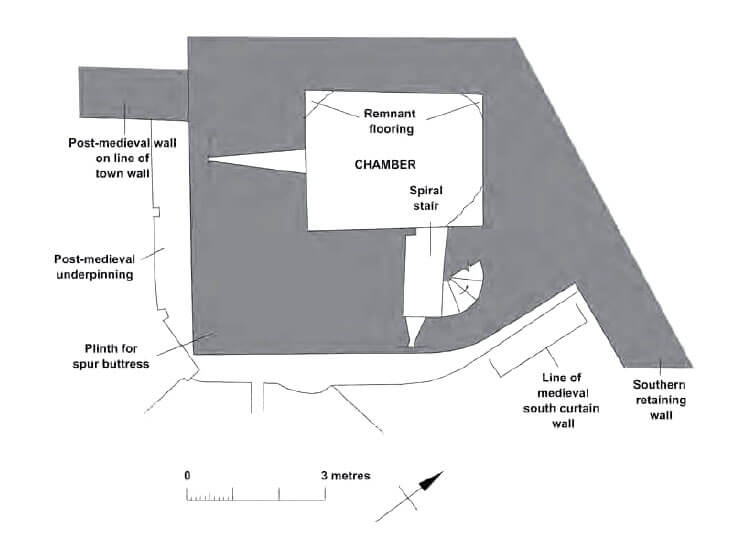

The upper (inner) bailey courtyard was fortified with massive walls 2-2.7 meters thick and at least 8 meters high, in the plan received a shape similar to an elongated rectangle with a slightly broken eastern curtain and a widened north-eastern corner, reinforced with a cylindrical tower. Another cylindrical tower, with a diameter of 8 meters and an average wall thickness of 2 meters, was on the opposite south-west side, in the corner of the defensive wall. It received a massive form with external facades reinforced with impressive, high buttresses or spurs (these elements were first used in England at Dover Castle, from where they came from France, e.g. from Chinon Castle). Inside, its four floors were equipped with four-sided rooms crowned with barrel vaults (the highest floor could be covered only by a ceiling) and connected by a cylindrical staircase embedded in the thickness of the wall. The walls of the tower were also pierced with straight, slit, inwardly open arrowslits, radially placed on each floor to cover the north-west, west and south foreground. The third tower, called the King’s Tower, located on the south-eastern side of the perimeter, had a semi-circular form in the plan, protruding mostly in front of the face of the wall. It was directed towards the lower ward, probably due to the impossibility of erecting the tower in the south-eastern corner due to the steep riverside slopes. Its floors were most likely separated by wooden ceilings.

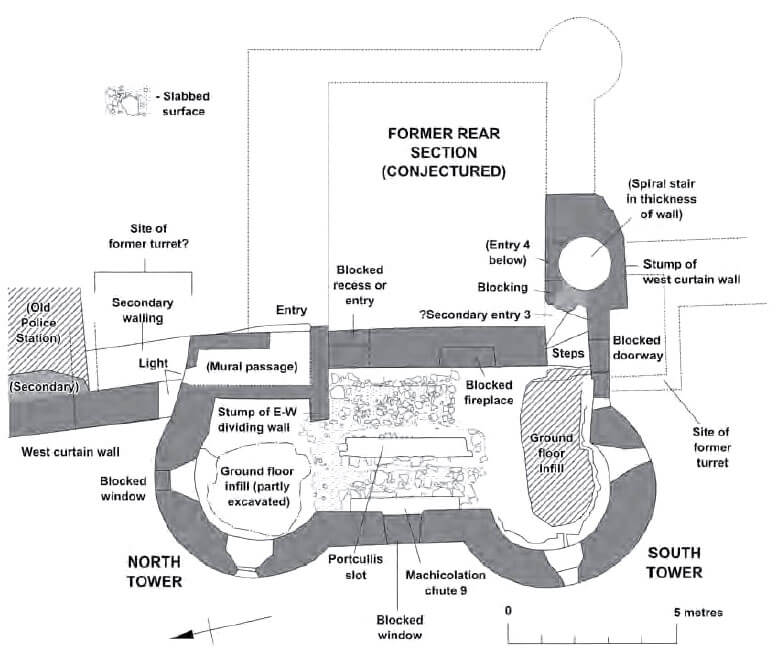

The main entrance to the 13th-century castle was on the west side facing the town. It was protected by a gatehouse, consisting of two towers, flanking a passage between them. The entire gate complex was erected in front of the face of the wall curtain towards the ditch, over which a wooden bridge supported by stone pillars was mounted. The depth of the ditch was at least 5.3 meters, while the width was about 15 meters. The defense of the gate was supported by the southwestern corner tower, and especially by the garrison placed on the mound’s fortifications on the northern side, taking advantage of the flanking location and the difference in height. Communication between the three aforementioned defensive works could be provided along the crown of the curtain walls.

The castle underwent another important reconstruction in the second half of the 13th century, around 1241-1278. It included the construction of a stone defensive wall in the eastern, outer ward and the addition of new administrative and residential buildings in the upper ward. From royal documents it is known that the castle had then, among others, a great hall, chapel, kitchen and stable. The hall was probably a stone, one-story building covered with a lead roof, adjacent to the building of the King’s Chamber, probably in the south-eastern part of the upper ward, perhaps at the back of the King’s Tower. Also, the kitchen had to be located not far from the above buildings, especially from the royal hall in which feasts, meetings and courts were organized. For fire safety reasons, however, it was probably not directly connected to them. The buildings of the lower ward had a secondary, economic role, with a distinctive stone stable building, while the defense rested there on two semicircular towers: one on the southern side and one in the eastern part. The former flanked a postern leading to the river, while the second stood at a distance from the gate directed to the northern foreground of the castle (occupied by urban buildings only in the 15th century).

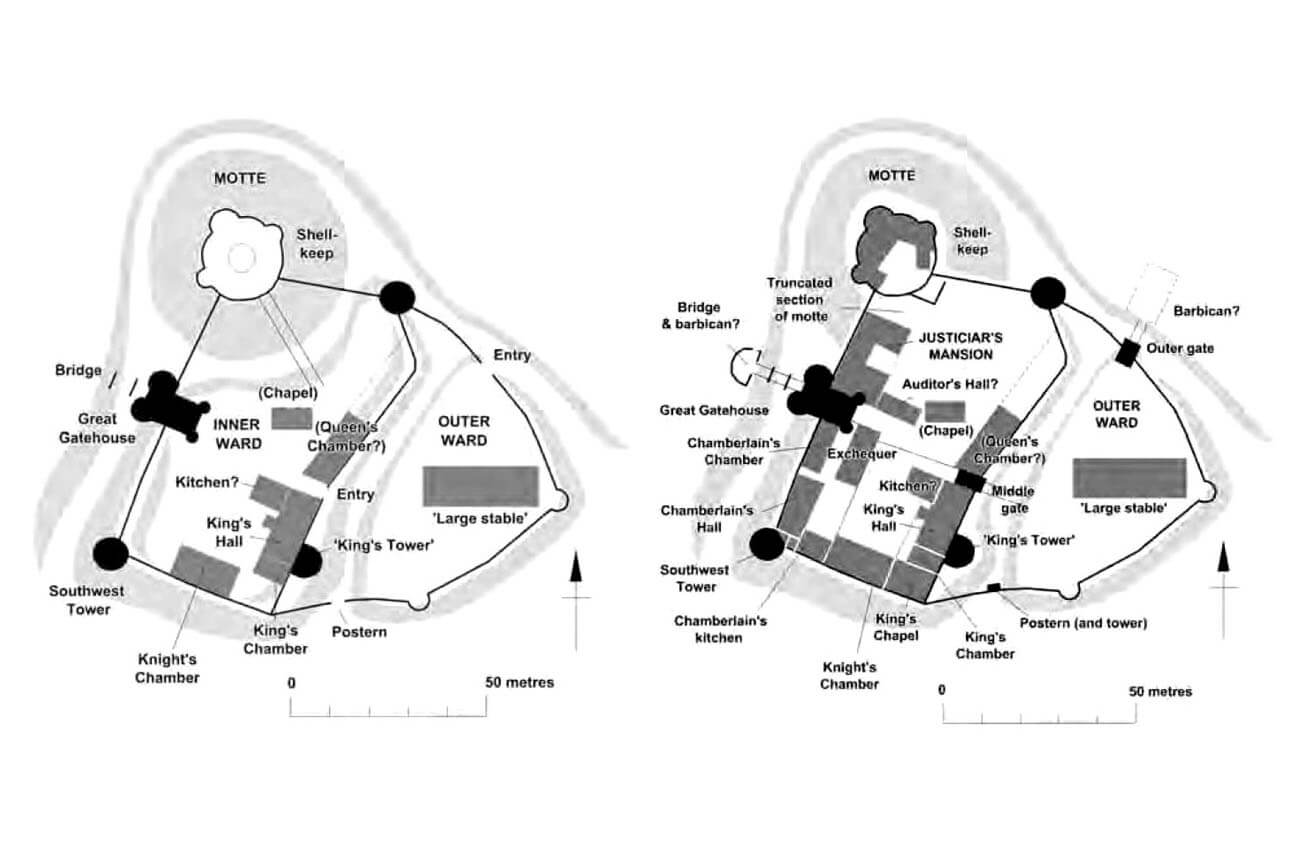

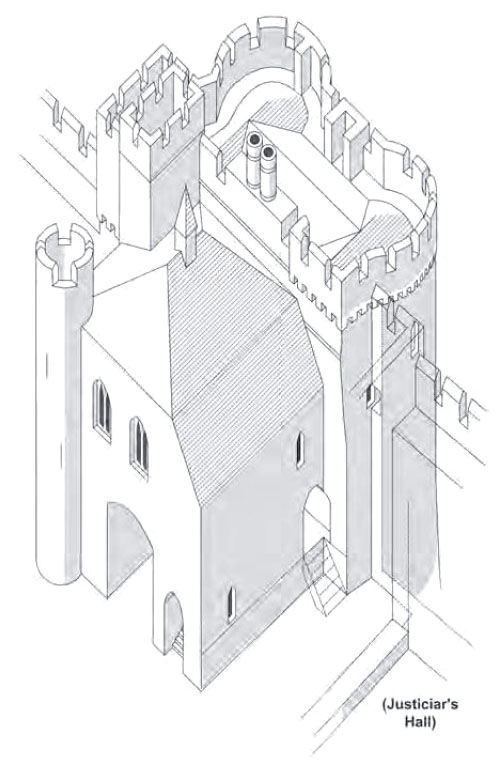

In the years 1279-1300, during the time of King Edward I, the castle was enlarged by more residential buildings. In 1306, the functioning of the Queen’s Chamber was recorded for the first time, erected about 20 years earlier and probably located north of the great hall. The southern curtain of the wall in the upper ward was supplemented with a rectangular building of Knight’s Chamber, i.e. rooms intended for important guests staying in Carmarthen. The west gate, extended by a part in the upper ward, with two corner communication turrets was also enlarged. The new part of the gathouse was intended for the residential chambers of the castle constable. Before 1289, the walls of the castle were whitewashed, probably to protect against moisture and perhaps to give the whole building a more impressive appearance, and after 1300 a new royal chapel was erected, dedicated to the St. Mary and Saint John the Evangelist, functioning simultaneously with the older castle chapel from the first half of the 13th century.

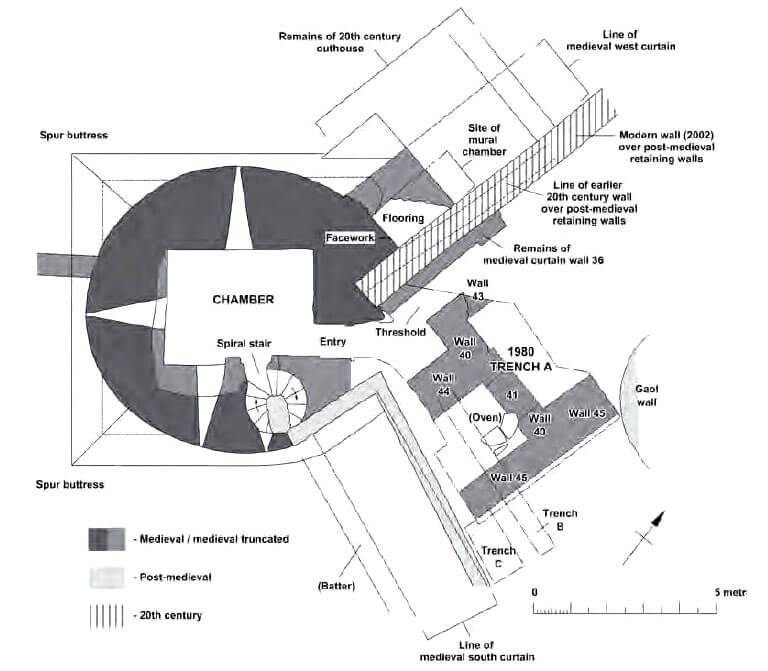

At the beginning of the fourteenth century, to obtain more living space, the fortifications of the motte and keep were modified. Until now, at its foot there was a dry moat (ditch), also running through the upper ward. It was then fil in the castle grounds, where the Justiciar’s Mansion was built. The buildings at the top of the mound were also transformed: the cylindrical wooden tower was removed, leaving a defensive wall with three semi-cylindrical half towers (shell keep), while its southern part was rebuilt. Inside the renovated perimeter buildings were erected, initially wooden and half-timbered, then partly of stone, adjacent to the walls of the shell wall. They were not recorded in documents, so could not have represented a high status.

During the fourteenth century, almost all the free space in the western part of the upper ward was occupied. In the time of Edward II, the castle became one of the main centers managing south and west Wales, which caused the need to erect a series of buildings for officials and their deputies, court and service. At that time, the buildings for the exchequer, chamberlain and the justiciar were erected. It is known that their main rooms were heated somewhat by already old-fashioned open hearths, with smoke escaping through the top of the roof, only smaller residential chambers were equipped with fireplaces with chimney ducts. The roofs were covered with lead, but slate and shingle were also used in less important buildings. The upper ward in the mid-fourteenth century was divided by a transverse wall, in the east joining the new gatehouse connecting both wards. This wall separated the royal buildings to the south from the justiciar’s house and chapel to the north.

During the reconstruction after the war damages from the beginning of the 15th century, the western curtain of the wall and the gate included in it were rebuilt. Probably the rear part was left (about 7×7.2 meters), but the northern communication turret was removed, the southern one was rebuilt, and new towers were erected on the foundations of the old gate towers, stylistically similar to those located in the main gate of the Kidwelly castle. They were 12.5 meters high to the level of the parapet (originally topped with a battlement), had a wall 1.5 meters thick and an external diameter of 5 meters. Above the 2.3-meter wide gate portal machicolations were suspended, and loop holes were hidden behind the first arcade of the passage, while the passage itself was closed at the time with a portcullis and a drawbridge, the rear part of which at the time of lifting the bridge was lowered to the pit created in the gate passage. In addition, a foregate was located in front of the ditch, perhaps built on the site of an older, destroyed barbican. The capture of the castle by the Welsh made the English aware of its weaknesses, because the defense of the southern part of the upper ward was strengthened with two four-sided towers, both attached to the face of the wall on the slope of the ditch.

Current state

Until today, the castle has survived in a vestigial form, considering how developed it was at the end of the Middle Ages. Currently, the most distinctive element is the main castle gatehouse consisting of two towers flanking the passage between them. Unfortunately, it back part has not been preserved. To the south of it you can see a not entirely preserved corner tower with prominent spurs. To the north of the gate are the remains of a keep or a shell keep. It’s wall follows the line of the medieval fortifications, but was largely rebuilt in the early 20th century and does not have its original height. Relics of one of the four-sided fifteenth-century (southern) tower also has survived, together with a section of the now lowered defensive wall. Most of the castle’s medieval domestic remains probably lie today buried beneath the County Hall and its car park.

bibliography:

Kenyon J., The medieval castles of Wales, Cardiff 2010.

Lindsay E., The castles of Wales, London 1998.

Ludlow N., Carmarthen castle, Cardiff 2014.

Ludlow N., Castell Caerfyrddin, Carmarthen Castle, Carmarthen 2007.

Salter M., The castles of South-West Wales, Malvern 1996.