History

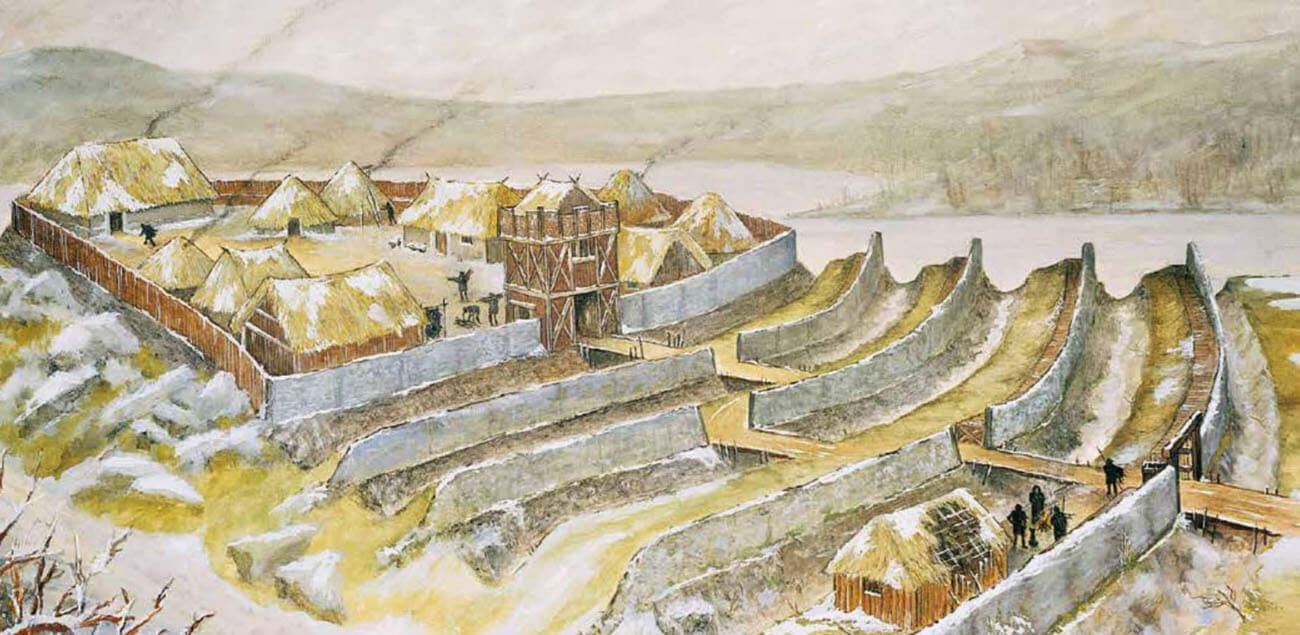

Carew Castle was built in the early 12th century on the site of old Iron Age ramparts. It was founded by Gerald de Windsor, Constable of Pembroke Castle, who around 1100 married Nest, Princess of Deheubarth, daughter of Rhys ap Tewdwr. Nest received the surrounding lands as part of her dowry, on which Gerald decided to build his seat, which was still a timber and earth building. It was first recorded as “domus de Carrio” in 1212. At that time, the castle was part of the domain of the earls of Pembroke, as an honorary barony obligated to the service of five knights.

Gerald de Windsor left a son, William, who before his death in 1173 probably extended the castle with a stone tower. It is also possible that Odo, one of William’s three sons and his successor in Carew, contributed to its construction. Odo died before 1207, leaving the estate to the next William. His lands were temporarily seized by King John for some unknown reason during expedition to Ireland in 1210, and returned two years later. The castle was further extended in the second half of the 13th century by Nicholas, who died in 1297, and again at the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries by his son of the same name, who died in 1311. Father and son were so proud of their rebuilt castle that they called themselves “de Carew”, despite also owning the estate of Moulsford in Berkshire.

The castle was spared the turmoil of wars in the 14th century, but the family gradually declined. Finally, in 1480, Sir Edmund Carew sold the family seat to Rhys ap Thomas, one of the leading supporters of the Tudor dynasty and King Henry VII. The new owner, a great and influential landowner, undertook the reconstruction, that transformed the medieval castle into a more comfortable late Gothic residence. Military functions had already receded into the background at Carew, as Rhys had a stronger castle in nearby Pembroke to defend. In Carew, in 1507, he organized a grand tournament to celebrate his knighting of the Order of the Garter. Until his death in 1524, Rhys enjoyed the unwavering trust of Henry VII and Henry VIII, thanks to which he was able to rule his Welsh estates without any restrictions.

In 1531, Rhys’s grandson, Rhys ap Gruffudd, fell into disgrace and was executed by King Henry VIII on charges of treason. Thus, Carew Castle became royal property, and then in 1558 it was given to Sir John Perrot, later Lord Deputy of Ireland. John Perrot carried out the last major modification to the castle. To enlarge his seat and improve its residential value, he founded the Renaissance north wing of the castle. Perrot died in 1592 before the work was completed, after being imprisoned in the Tower of London on charges of treason. Carew was granted to his son Thomas by an act of grace, but he died in 1594. The castle was once again reverted to the Crown, through which it was leased several times to different tenants, before being purchased by the English branch of the de Carew family in 1607.

During the English Civil War of the 17th century, the castle was fortified by the Royalists. After changing hands three times and having its south wall partially destroyed, it was returned to the owners after the end of hostilities. The Carew family lived in the east wing until about 1686, when George, the then owner, was named for the last time from Carew Castle. In 1687 Katherine, George’s widow, granted a lease on part of the Welsh estate, and wrote her name from Crowcombe. For a short time the tenants used part of the buildings for farm purposes, but the castle was soon abandoned and fell into ruin. Repairs did not begin until 1984.

Architecture

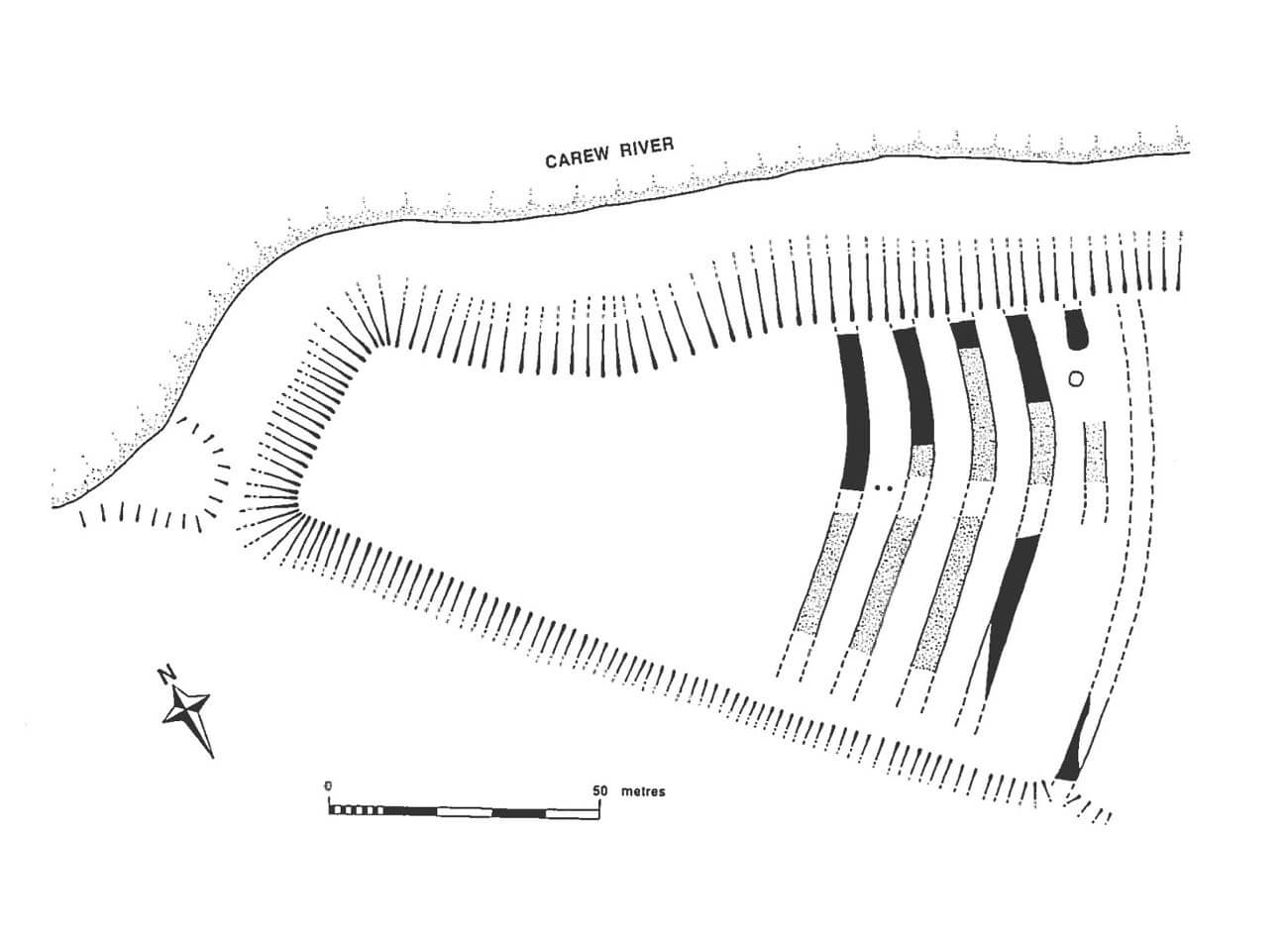

The castle was situated on a small elevation of land on the southern bank of the Carew River, to the west of which was the mouth of the Cleddau Ddu and the sea, which made possible to bring supplies in large boats, while at the same time ensuring control of the nearby ferry. At the time of the castle’s construction, this area was occupied by the remains of Iron Age fortifications, in the form of five or six earth ramparts and the ditches preceding them, which cut off the headland to the east. Despite this, the site chosen for the castle did not have great defensive value, unless there were marshy or boggy areas on its further foreground. Strategic considerations had to be the key issue, with the possibility of supplying the building by sea being the most important. During the construction of the bailey, the old ramparts were filled in and levelled, in order to provide space for a new defensive structure.

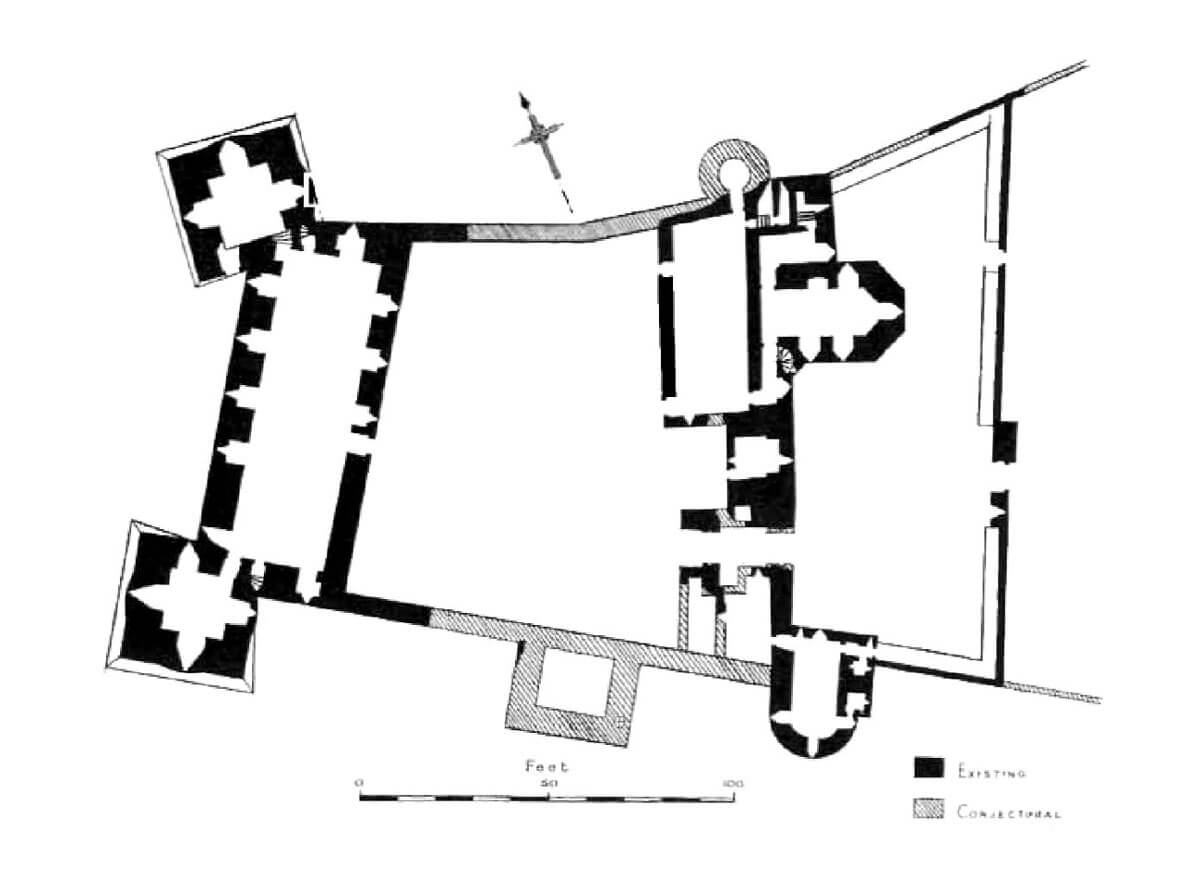

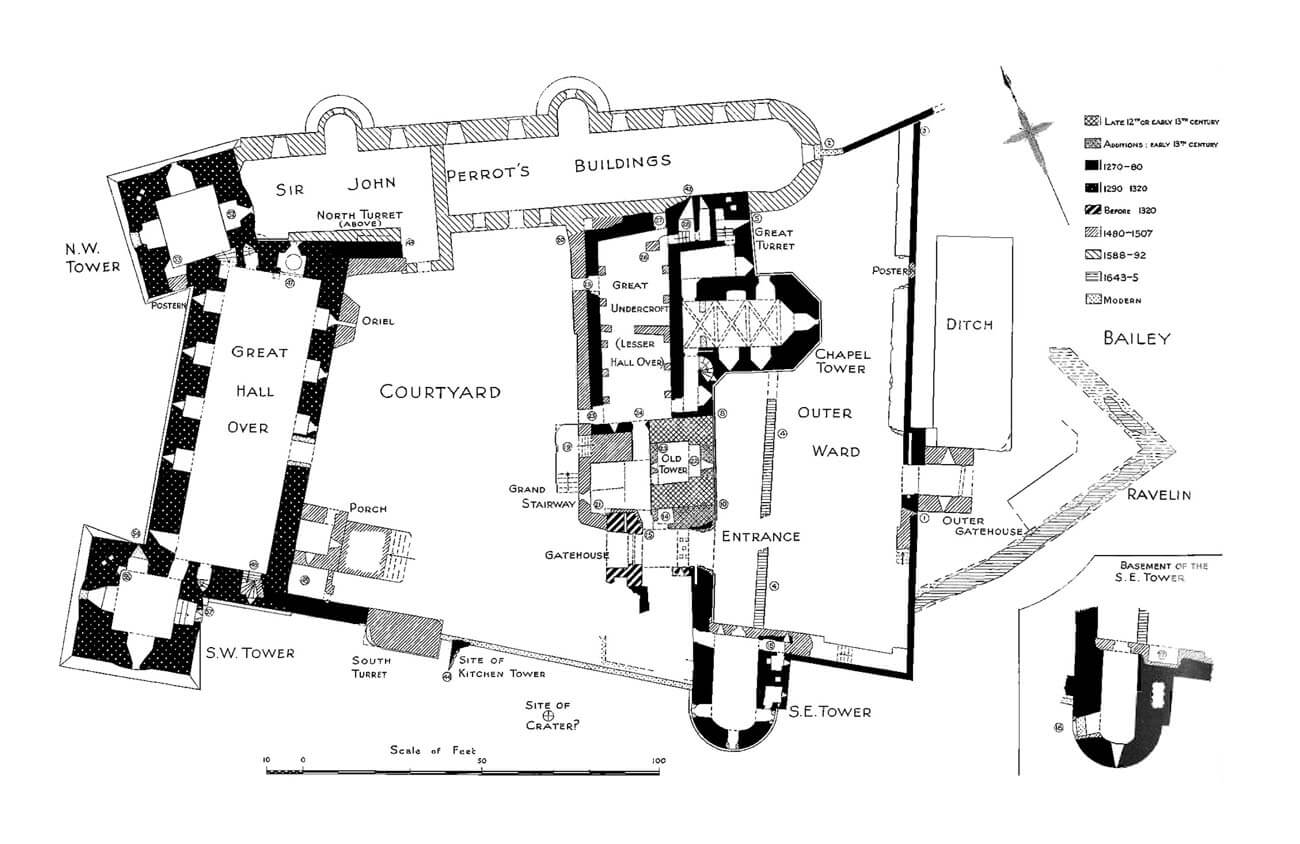

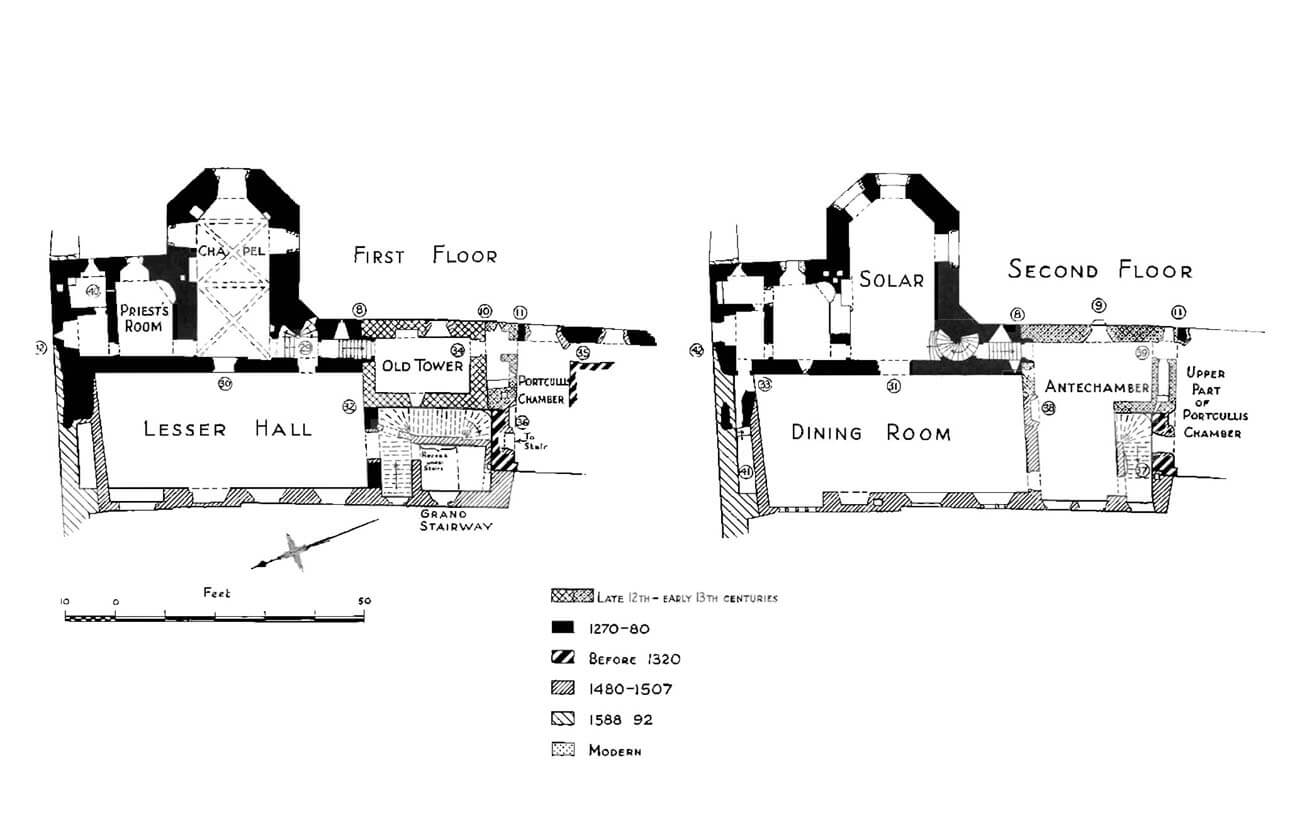

At the end of the 12th century, Carew Castle had the form of a relatively large, but mostly wooden and earthen structure. The oldest stone structure was a quadrangular residential tower, which served as a gate on the ground floor. It was situated behind the old Iron Age ramparts and behind the ditch, more or less in the middle of the front part of the castle, where it was probably incorporated into the palisade perimeter of the fortifications. Shortly after the tower was completed, and perhaps even during construction work, a number of changes were made to the original design. The wall was thickened from the south to accommodate a latrine with a drain, and it was also raised so that there were two low storeys above the gate passage instead of one. Around the middle of the 13th century, the gate arch was blocked, while a small room was built on the ground floor of the tower, which could be reached from the inner courtyard.

A thorough reconstruction from the third quarter of the 13th century and the beginning of the 14th century led to the creation of a fully stone defensive perimeter of the castle. A stone wall was built on a plan similar to a quadrangle, in which the old tower was incorporated on the eastern side. It was in line with the new curtain wall from the front, so that its entire block was inside the courtyard. In addition, defense was provided by two corner cylindrical towers on the western side, a semicircular south-eastern corner tower, a polygonal north-eastern tower with a castle chapel and an adjacent corner building in a tower-like form. Probably in the middle of the southern curtain there was originally another semicircular or quadrangular tower, among others housing a kitchen. The northern side of the castle, as the safest (facing the river), was most likely protected by a slightly bent curtain wall. Only near the north-eastern corner could there possibly be a small circular turret. As part of the work on the eastern part of the castle, the original ditch was filled in and a new moat was made, dug a little further to the east.

The western towers were equipped with characteristic prominent spurs, acting as buttresses and limiting blind spots of fire. Both had a diameter of about 10.5 meters, but were situated irregularly, because the north-western one was set at a 40-degree angle to the hall building. In this way, the postern was masked, which functioned in the lower part of the tower. The north-western tower was distinguished by its lowest location among all the castle buildings, which resulted from the slope of the terrain towards the river. It also had thinner walls and more spacious interiors compared to the south-western tower, due to its location in a safer place. Both towers were topped with a parapet placed on consoles, behind which there was an unroofed defensive gallery. Additionally, guard turrets protruded above it, which were an extension of the staircases. The interiors of both towers contained a vaulted ground floor on a quadrangular plan and two upper floors with polygonal rooms. The upper floors could have been used for living purposes, as they were equipped with fireplaces and latrines with drains leading out through the spurs. The ground floors with cross-shaped loopholes were used exclusively for defensive purposes.

The south-eastern tower was distinguished by its location, as it was entirely protruding in front of the main defensive perimeter and connected to the external wall of the zwinger. The semicircular part was directed south, towards the castle foreground, while the eastern wall directed towards the outer bailey was thicker than the others in order to accommodate latrines within the thickness of the wall. For this reason, the zwinger wall was connected to the rear part of the tower, not the front one, so that feces would fall outside the castle. Another characteristic feature of the tower was an exceptionally high parapet, pierced with slit-shaped loopholes. As in other towers, it was mounted on corbels protruding from the face of the walls. Inside, the first and second storeys were covered with simple barrel vaults, and the third one with a ceiling or an open roof truss. The ground floor originally had a purely defensive role. The upper floors had access to latrines, but only the highest storey had a fireplace. There was no staircase between them, so each level had to be accessed by a separate door, in the case of the upper floors leading from the neighbouring building by the gate, and in the case of the ground floor connected with the zwinger. It is possible, however, that the vaults were added later, while initially ladders operated between the floors. In addition, at the end of the Middle Ages, when defensive considerations ceased to play a role, a postern leading outside the castle was pierced in the ground floor.

The main residential and representative space of the castle was at the western part of the inner courtyard. The building of the great hall occupied the entire length of the western curtain, between the two corner towers. It had dimensions of 25 x 8 metres and very thick walls reaching from three sides up to 3 metres wide, apart from a slightly thinner wall facing the courtyard. A wall-walk ran in their crown, similarly to the curtains protected by a crenellated parapet. On the first floor level, the building housed a representative great hall, covered with an open roof truss and set above the vaulted storage rooms on the ground floor. The ground floor was accessible by northern and southern stairs, created in the thickness of the massive wall, and also connected with the neighboring towers. It was lit by slit openings, splayed from the inside and set in wide niches. The vault was divided into two rows of bays, perhaps separated by central pillars. The interior of the great hall on the first floor was also connected with the corner towers. In the southern part of the hall, there was a timber gallery for minstrels, accessible by stairs in the thickness of the wall. Its upper part was opened to the hall, while the lower part could be cut off by wooden screens, creating an entrance vestibule before the main part of the hall. The great hall was lit by three larger windows facing west, one south window above the minstrels’ gallery and three east windows, the north one of which was transformed into a late Gothic three-sided bay window at the beginning of the 16th century. A narrow passage was created in its north wall, leading to the latrine in the turret at the castle’s north curtain wall. The great hall was heated by two large fireplaces, set opposite each other in the middle of the longitudinal walls.

At the beginning of the 16th century, the entrance from the inner ward to the great hall was preceded by a vestibule, created near the south-west corner of the courtyard. The vestibule had as many as three storeys, the middle of which was an entrance preceded by wide stairs. The interior of the vestibule communicated the courtyard with the great hall, as well as with the south passage, which on a wooden porch supported by stone consoles, led along the curtain wall to the tower with the kitchen. The ground floor of the vestibule was filled with a small vaulted chamber, accessible from the north, lit by slit openings from the south and east. The second floor opened onto the courtyard with a large quadrilateral window, placed above a coat of arms panel with the insignia of King Henry VII. The vestibule was crowned with an unroofed wall-walk hidden behind a battlemented parapet mounted on consoles protruding from the wall face.

The building of the so-called lesser hall was located in the north-eastern corner of the courtyard, between the corner tower and the former gate tower. Initially, it housed two storeys: a vaulted ground floor with a utility function and an upper residential chamber. The ground floor of the building was a dark, spacious room measuring approximately 6 x 15 meters, divided into two chambers since the end of the 15th century and covered with a segmental barrel vault, supported by several quadrangular wall pillars. In the eastern part of the building, there was a long passage, lit by a widely splayed arrowslit. It connected the utility ground floor with the three-bay vaulted lower part of the tower with the chapel and the adjacent tower-like building in the corner, as well as with the spiral staircase. Door at the end of the passage, just in front of the tower, being closed with a bar set into the hole in the wall. The hall on the first floor was originally topped with an open roof truss. It was connected with the chapel in the tower, and indirectly with the priest’s living quarters, located in the tower-like building on the north side. Quarters consisted of a larger chamber with a fireplace, a smaller unheated room and a latrine chamber. A very similar set of rooms was also located on the third floor of the corner building. The chapel itself was covered with a two-bay cross-ribb vault and closed on three sides on the east. It was equipped with a stone piscina, a wall niche and a stoup at the entrance. A very unusual solution was to place a fireplace in the chapel, which was probably original element, not secondary insertion. Above the sacral room, there was still a residential space on the third floor of the tower. The north-eastern corner building exceeded the tower with the chapel by a fourth floor with a single room, probably added in the late Middle Ages.

At the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries, the complex of north-eastern residential and representative buildings was raised by a third floor and enlarged by an extension measuring approximately 6 x 7.6 meters, added to the rear part of the old gate tower, which was partially demolished and partially rebuilt. In the ground floor of the new part, a room with a small fireplace in the southern wall was placed, connected to the gate passage in the south and the lower level of the lesser hall in the north. Next to it was a tight ground floor room of the old tower, covered with a high barrel vault, i.e. the original gate passage from the end of the 12th century. The first floor of the extension was occupied by a wide staircase, accessible from the outside by a ramp, connected to the main part of the lesser hall and to another small, fireplace-heated room at the back of the old tower. On the second floor, the staircase led to a larger room, created by combined extension and the old tower. This room was also heated by a fireplace, although it was placed in the northern wall.

The entrance to the inner ward was through a gate located to the south of the original tower from the end of the 12th century. The newer gate from the end of the 13th century, even after the expansion at the beginning of the 14th century, was not a very sophisticated construction. It was equipped with a passage just over 9 meters long, closed at the back by double-winged gates with three bars and a portcullis. Presumably, additional gates were located at the front. In the crude, detailless vault, there were three so-called murder holes, i.e. openings for striking from above. Additionally, one slit loophole flanked the passage from the south. This was probably considered sufficient security, especially since the entrance was flanked by two towers in close proximity, and from the east there was a 15-meter-wide zwinger, with an external wall and a late Gothic quadrangular gatehouse measuring 6 x 5.5 meters, preceded by a ditch about 6.6 meters wide. The outer gatehouse was closed on the ground floor with door blocked by a set of three massive bars, pushed into holes in the wall, but it had no portcullis, and certainly no drawbridge. On the first floor there was a doorkeeper’s room heated by a fireplace, from which a spiral staircase led to the upper, unroofed gallery. Its parapet was set on a row of stone corbels from the outside, while the staircase was raised to form a small guard and observation turret. A small latrine was also created in the parapet for the convenience of the guards.

The fortifications of the eastern zwinger separated the castle from the outer bailey, also fortified by a stone wall with a gatehouse preceded by a ditch in the east. The outer bailey wall and both gatehouses were topped with a new battlement towards the end of the Middle Ages. Its reduced crenels, however, were small and probably served more decorative and symbolic purposes than constituted real protection for the defenders. The residential and utility buildings of the outer bailey were probably attached to the inner elevations of the defensive wall or located in close proximity to it, so that there was a thoroughfare to the main part of the castle in the middle. Most of the buildings of the outer bailey were probably of light wooden or half-timbered construction, but a stone building about 22 meters long stood out in the northern part of the courtyard, about 4 meters away from the defensive wall.

Current state

The castle has survived to the present day in the form of a relatively well-preserved ruin, with a visible almost complete spatial layout. Only a fragment of the southern wall does not have its original height today, and is also partly a modern patching of a breach caused by the 17th-century battles. In addition, the defensive wall of the outer bailey has not survived, and almost all buildings today do not have roofs (only the building of the lesser hall is currently roofed). Unfortunately, the medieval appearance of the castle was partially blurred by the reconstructions from the second half of the 16th century, especially the addition of the northern wing with large windows in the Elizabethan Renaissance style. Most of the architectural detail comes from the late Gothic rebuilding from the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries and from the period of Renaissance construction works. The castle is leased and managed by the Pembrokeshire Coast National Park, which makes it available to tourists.

bibliography:

Carew Castle Archeological Project, red. D.Austin, Lampeter 1995.

Kenyon J., The medieval castles of Wales, Cardiff 2010.

King D.J.C., Perks J.C., Carew Castle, Pembrokeshire, “The Archaeological Journal”, Vol. 119/1962.

Lindsay E., The castles of Wales, London 1998.

Salter M., The castles of South-West Wales, Malvern 1996.

Walker R.F., Carew Castle, „Archaeologia Cambrensis”, Vol. 105/1956.