History

The first castle in Caldicot was probably built in the first quarter of the 12th century on the initiative of Walter Fitz Roger, Sheriff of Gloucester, who funded wood and earth motte fortifications. After the death of his son Milo Fitz Walter and the death of his five sons without heirs, the castle passed into the hands of Humphrey II de Bohun, Earl of Hereford, who married Margaret, Milo’s eldest daughter. It was most likely his grandson Henry who funded the stone keep before 1220, and his son, Humphrey de Bohun, the second Earl of Hereford, after 1221 and before 1275 built the perimeter of the castle’s stone walls. The next period of construction activity lasted from the end of the 13th century to the second quarter of the 14th century, when a complex of impressive residential buildings was created in the castle.

The Bohun family became a powerful family and owned Caldicot for over two centuries. When Humphrey de Bohun, the seventh Earl of Hereford, died without a male heir in 1373, his estate passed to his daughters, Eleanor (Alianore) and Mary. In 1381, Mary de Bohun married Edward III’s grandson, Henry Bolingbroke, later King Henry IV, while Eleanor, who was the heiress of Caldicot, had married in 1376 Thomas of Woodstock, later Duke of Gloucester. As he was the uncle of the English King Richard II and played an important role at court, he rarely stayed at Caldicot Castle. It was only the civil unrest and the peasants’ revolt that prompted Thomas to spend more time on his Welsh estates. In the 1380s, he ordered the expansion of the south gate, which from then on housed the main living quarters in the castle, as well as the tower known as Woodstock Tower.

As time passed, relations between the king and his uncle became strained. In 1397, Thomas was kidnapped, accused of treason and murdered, and his estates were partly confiscated and partly given to his daughter, Anne Woodstock, who married Edmund, Earl of Stratford. Their son Humphrey retained control of the castle and became the first Duke of Buckingham. In 1521, after the death of Thomas Woodstock’s last descendant, Edward, 3rd Duke of Buckingham, who was also executed for treason, Caldicot became part of the Duchy of Lancaster. The castle ceased to be a residential residence and was leased to various owners together with the surrounding estate. The tenants were mainly interested in the income from the estates, so they did not invest in the old buildings, and it gradually fell into neglect and then ruin.

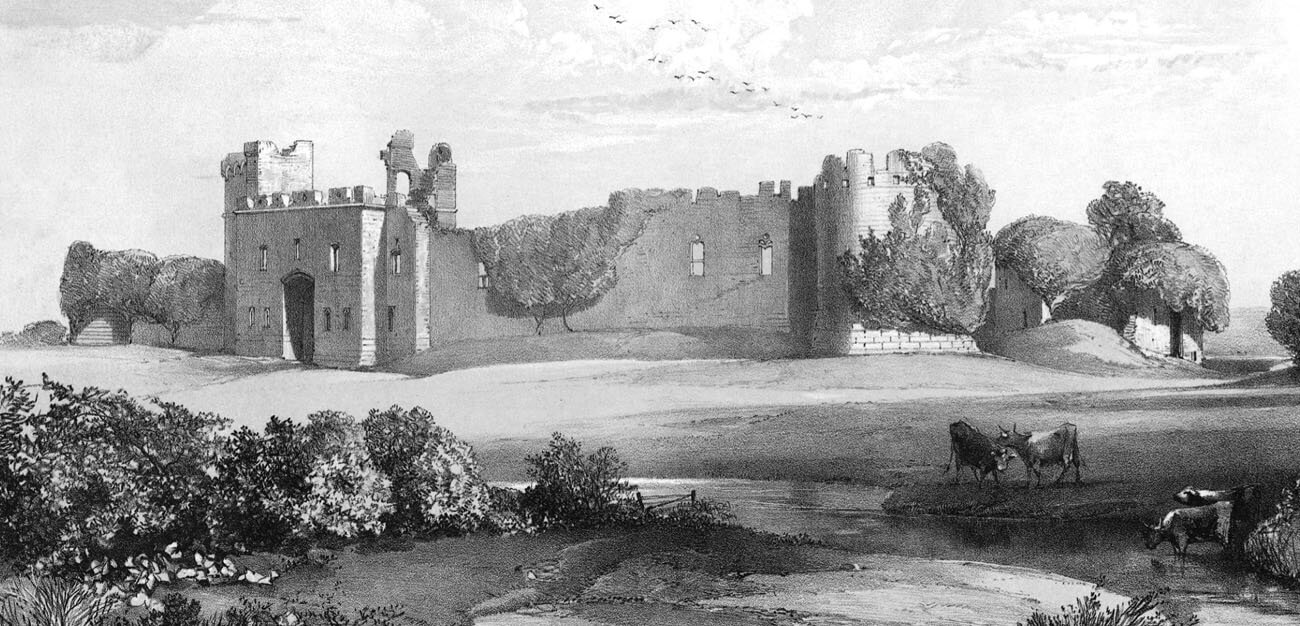

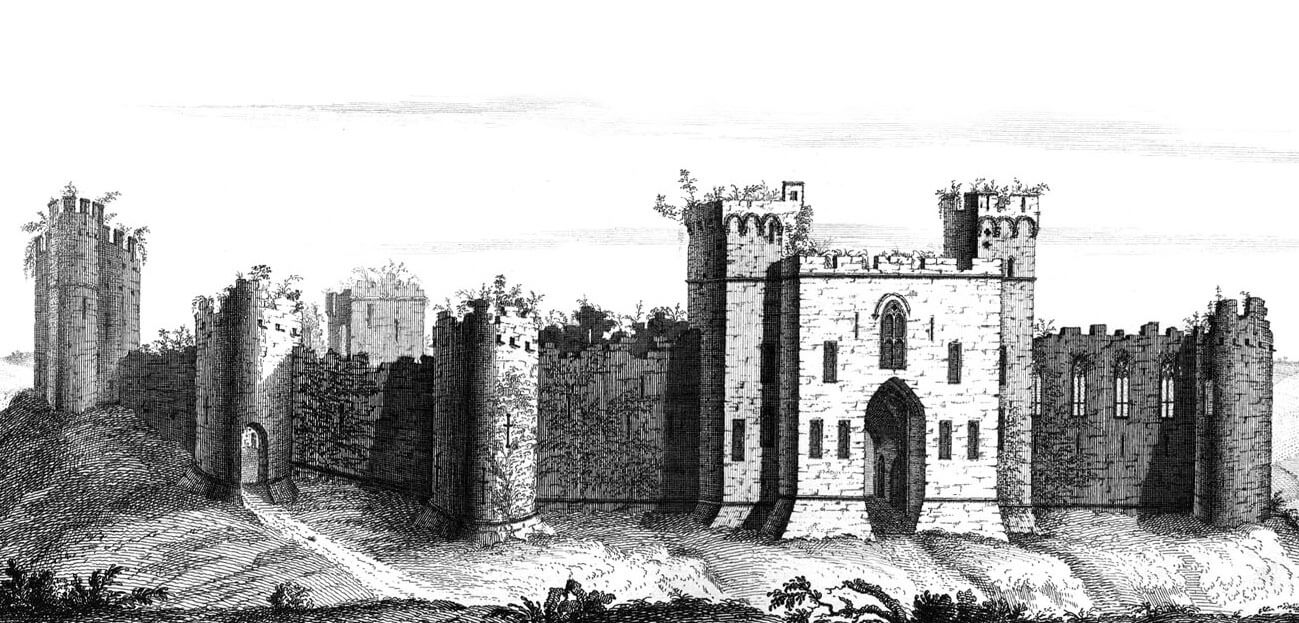

During the 17th century Civil War, Caldicot was garrisoned by Royalists, which contributed to partial destruction of the castle in the late 1640s by Parliamentarian forces. Until the mid-19th century, the picturesque ruins were occasionally used by the local village community. In 1885, it were sold to the noted medieval castle enthusiast, Joseph Richard Cobb, who, as at Manorbier and Pembroke, began a renovation and partial rebuilding, with the aim of transforming Caldicot into a family home. The castle remained a private residence until 1963, when it was purchased by a government agency.

Architecture

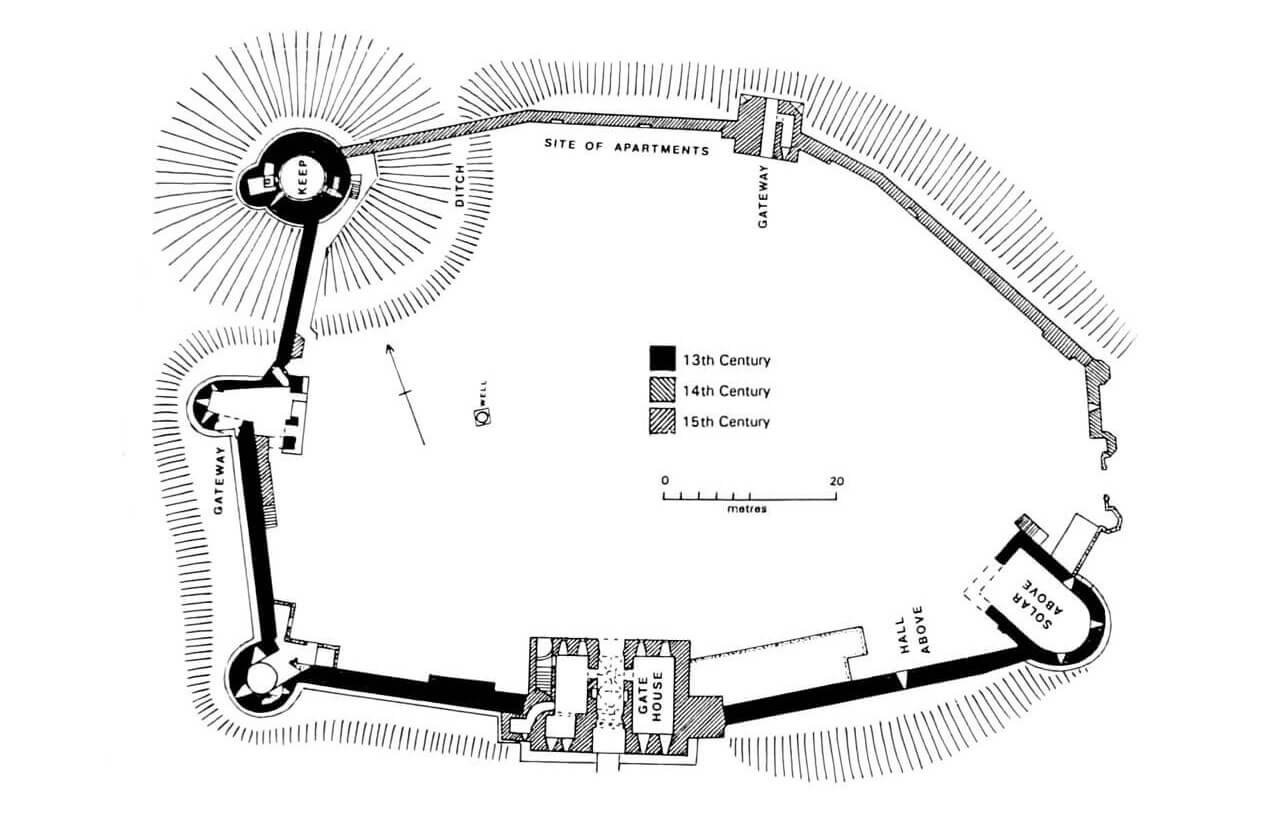

The castle was built on a small outcrop of land, in a bend of the Nedern stream, on the western side of one of its many bends. This area was devoid of any major natural obstacles, except for the marshy and boggy meadows on both sides of the stream, especially near its mouth in the south into the wide estuary of the Severn River. The castle had a shape close to an oval measuring 100 x 66 meters. At the end of the 13th century, it consisted of a defensive wall connected to the north with a round keep situated on an earthen mound, and reinforced with a horseshoe-shaped south-eastern tower and a cylindrical south-western tower. The entrance gate to the spacious inner ward was initially located on the western side, placed in the Bohun Tower in the shape of an elongated horseshoe, with the gate passage situated similarly to Pembroke Castle in the side wall. The outer bailey was located to the west of the castle.

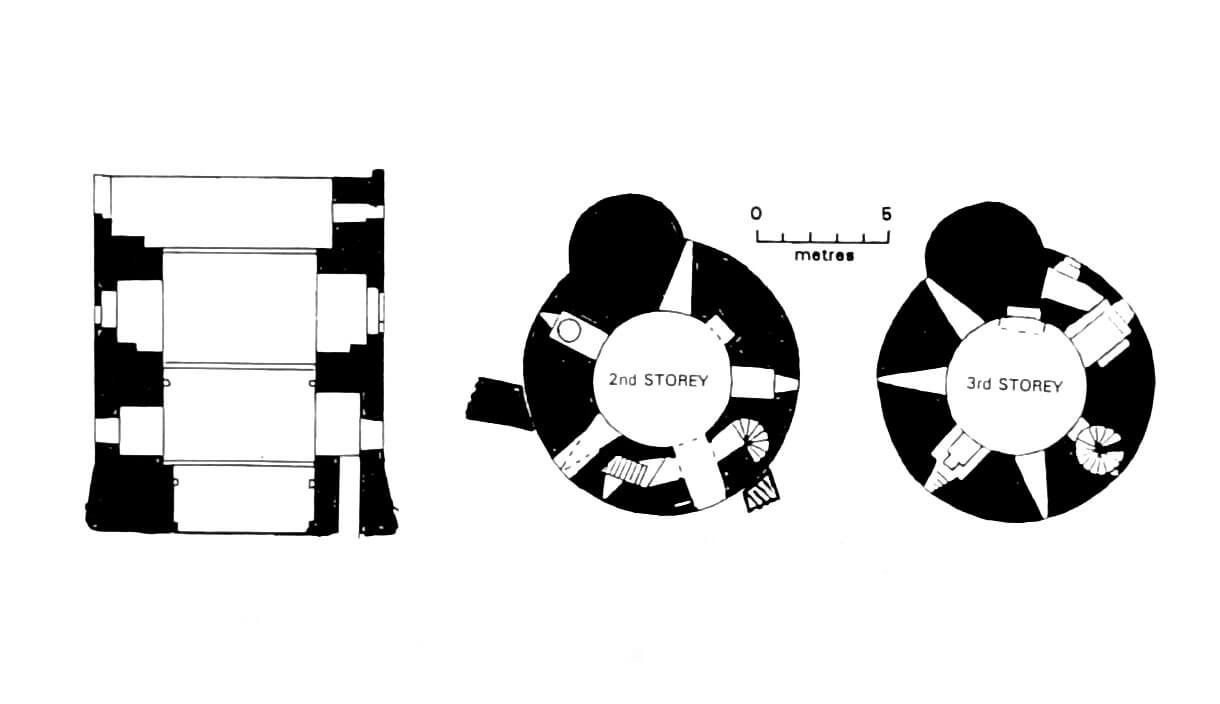

The oldest stone element of the castle was a cylindrical keep with a diameter of about 10.6 meters and a height of at least 13 meters, located in the north-western part of the castle, on a small earth mound. This motte was surrounded by a ditch, also dug from the side of the inner ward marked by the later perimeter of the walls. The keep was built of sandstone ashlar laid in even layers, unlike the perimeter wall, made of smaller and only roughly processed sandstones. At the base it was clasped with a plinth with a slightly chamfered cornice, while at the top it was surrounded with a wall setbeck, above which a row of quadrangular openings was created, probably used for mounting a hoarding. The tower’s crowning was originally in the form of a battlemented parapet. The keep resembled similar structures from Bronllys or Tretower, except for a small, semicircular bulge protruding from the western part of the building, i.e. towards the foreground of the castle. Turrets of this type usually contained staircases, but at Caldicot it had only a prison chamber at the bottom. The upper space was filled with a solid mass of masonry.

The massive 2.7-metre-thick walls of the keep contained three floors above the ground floor embedded in the mound. The lowest floor may have been a prison, or more likely a larder or storeroom. It was equipped with a well in case of siege and a high ventilation opening. Entrance to the tower was by ladder or wooden stairs to the first floor level, first to a corridor-like vestibule in the thickness of the wall, and then to the main room. The entrance door to the keep was blocked by a bar pushed into a hole in the wall. Communication down to the dark chamber at the ground floor was provided by stairs in the thickness of the wall, and from there a trapdoor in the floor led to the prison cell mentioned above. A spiral staircase led upwards, as did the stairs downwards, accessible from the entrance corridor. The room on the first floor was equipped with four evenly spaced arrowslits and a fireplace. The main living chamber was located on the second floor. It was well lit by two windows with side seats (one each to the north and south), it was also heated by a fireplace, and the passage from the northern window recess led to the timber corbeled latrine. At the level of the highest defensive floor, a pointed arch portal provided communication with the hoarding.

The horseshoe gate tower was significantly protruding towards the moat and asymmetrically connected to the adjacent curtain walls, which is why the southern wall on the outer side of the perimeter was shorter than the northern wall. A gate passage was placed in the shorter southern one, most probably reached by a wooden bridge placed over the ditch. The passage was set quite high, above the cornice of a prominent batter. The interior of the passage was closed with a portcullis and protected by two so-called murder holes, used to strike the enemy from the upper storey. The crown of the gate tower walls, similarly to the keep, could be crowned with a hoarding, mounted to quadrangular sockets in the wall and on corbels protruding from the face.

The cylindrical south-western tower was 7.2 meters in diameter. It protruded almost entirely in front of the adjacent walls, which allowed for flanking fire. It was distinguished from the neighbouring curtains and the gate tower by the lack of a base cornice and by the construction material, which was more reminiscent of that used in a keep. It was topped with a battlement with loopholes, but could also be equipped with a wooden hoarding, mounted in sockets and on corbels. In addition, defence was provided by cross loopholes arranged on two levels, with circular enlargements in the lower parts for crossbowmen (oillets). Inside, the tower had two storeys connected by stairs in the thickness of the wall, so it was not much higher than the wall-walk connected to it.

The south-eastern tower was 10 metres wide and 15.6 metres long. Although it differed in plan from the south-western tower, its base was also reinforced by the batter of the base (enclosed by a cornice), the walls were pierced with cross-shaped loopholes, and it crowning was a battlement with loopholes in the merlons and a hoarding. Above the utility and defensive ground floor, the tower housed a living room. It was heated by a fireplace and lit from the field side by three rectangular windows, probably secondarily set above the cross-shaped loopholes. Inside, these windows had stone seats, created in such a way that a seated person had a loophole at the height of their legs. Additionally, a large window with a two-light tracery was created in the north-eastern side wall on the first floor, set from the inside in a high recess with a moulded frame.

Around the first quarter of the 14th century, or at the latest in the 1340s, a wooden building of a representative great hall was erected at the southern curtain of the defensive wall, on the western side of the horseshoe south-eastern tower. The external wall of the building was formed by the then rebuilt stone defensive wall, at the base of which two large pointed recesses of unknown purpose were left. In the ground floor of the building, a storage and utility room was created, lit from the southern side by slit openings. On the first floor, there was a representative hall, lit by three pointed tracery windows. To the west of it, there could have been residential rooms with a single narrow window with an ogee arch and a more decorative two-light window. A fragment of the curtain wall on the eastern side of the horseshoe tower was rebuilt at the end of the 14th century or in the 15th century. From then on it consisted the external wall of the building equipped with three polygonal turrets at the front. These turrets were equipped with narrow slit openings, and the building with larger single and two-light Gothic windows.

In the first half of the 14th century, Humphrey de Bohun erected a new gate complex in the southern part of the perimeter. In the second half of the 14th century, it was rebuilt and enlarged, receiving not only defensive functions but also residential ones. It consisted of the main, rectangular building, flanked by two slender quadrangular latrine turrets: a smaller western one and a larger eastern one. All three parts on the ground floor were reinforced with a batter, descending from the outside to the bottom of the ditch. All were also topped with a battlemented parapet, set on consoles in the turrets and creating machicolations. The centrally located passage was equipped with two portcullises, two gates and so-called murder holes. The latter were pierced in the segmental vault, between the moulded arches in front of the first portcullis. In the front part of the passage, a side opening for the doorkeeper was also pierced, while in the middle part two segmental niches for sedilia were created. Above them, two bays of ribbed vaulting were spread, set on figural corbels. The gate passage was flanked by two guard rooms, accessible through pointed portals. Interestingly, from the front side, these rooms were equipped not with arrowslits, but with decorative windows with trefoil heads, set in moulded rectangular niches. On the first floor, accessible by straight stairs set in the thickness of the western wall, there was one large residential chamber, connected by long passages in the thickness of the walls with side turrets. Its lighting was provided by fairly wide windows set in shallow projections, originally supported by single consoles in the form of bas-relief heads. The windows of the first floor had trefoil tracery with wide central petal closed with ogee arch.

In the second half of the 14th century, the north-eastern tower was also built, called the Woodstock Tower after its founder. It received a quadrangular base measuring 7.8 x 7.3 metres, with truncated front corners above. On the ground floor, there was a narrow gateway closed with a portcullis, and three floors equipped with residential chambers. Each of them was heated by a fireplace and lit by ogee windows facing the moat. There were also passages on the floors ending with latrines. Vertical communication was provided by a spiral staircase and a pointed portal on the first floor, accessible by external stairs from the courtyard level. The tower’s defensive capabilities were enhanced by machicolations placed only on the outside. Probably, along with the tower, the entire north-eastern part of the perimeter wall was rebuilt, which was than much thinner than the older sections, reaching 1.4 metres wide. The presence of three fireplaces in the wall on the courtyard side, which heated the non-preserved wooden or half-timbered buildings, would also indicate that these fortifications were built later.

Current state

The castle has survived to the present day in very good condition, mainly thanks to the reconstruction from the late nineteenth century. Fortunately, it did not interfere strongly with the medieval, historic substance, thanks to which the original character of the castle was preserved. Currently, you can see practically the entire perimeter of the castle walls, a cylindrical keep, three towers, a west gate with no surviving inner part and a south gate which has undergone the largest reconstruction. The castle together with a small museum is available for free for sightseeing, and there are often outdoor and occasional events.

bibliography:

Kenyon J., The medieval castles of Wales, Cardiff 2010.

Lindsay E., The castles of Wales, London 1998.

Newman J., The buildings of Wales, Gwent/Monmouthshire, London 2000.

Salter M., The castles of Gwent, Glamorgan & Gower, Malvern 2002.