History

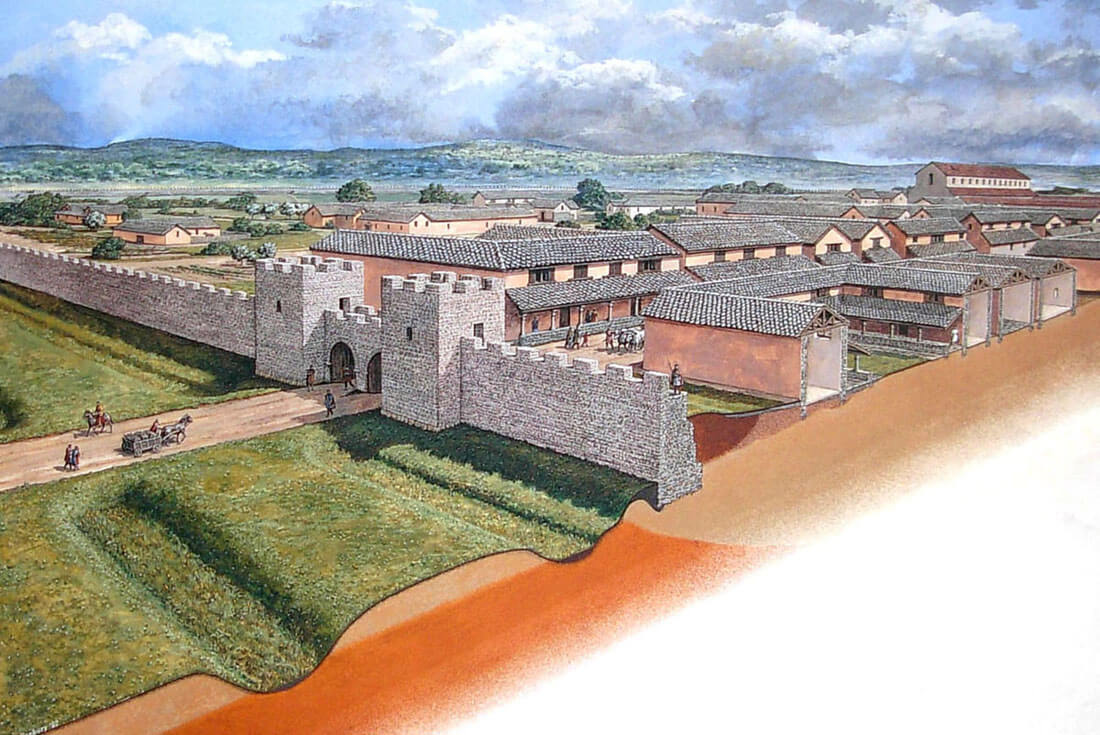

Caerwent, or Roman Venta Silurium, was founded around 75 AD on the lands of the Celtic tribe of the Silures, conquered the previous year by Julius Frontinus. During the campaign, the 2nd Augusta Legion established the fort of Isca Augusta on the lands of the Silures, as well as a network of other auxiliary forts to keep the conquered tribe in submission. The legionaries came with their families, officials, engineers and construction specialists. Some of the settlers probably settled near the Silures’ market settlement, which gave its name and origin to the Roman town of Venta Silurium. This town was located on an important Roman road between Isca Augusta (Caerleon) and Glevum (Gloucester). Unlike the above, it was founded primarily for civil administration, not military purposes, but its initial development may have been related to the production of pottery, glass, and metal work for the Roman army.

The process of Romanization of the Silures was fast. Initially they were merely dediticii, citizens without status or political rights, but Venta Silurium soon became a self-governing town, as evidenced by the construction of a forum and basilica in the first half of the 2nd century. As a civitas Venta Silurium became a tribal assembly place where courts were held and administrative activities were carried out. Military supervision of the Silures was also reduced quite quickly, especially after 122, when a large part of the resources and troops were moved to the northern border in connection with the construction of Hadrian’s Wall. By the end of the 2nd century the town was bustling with life, probably numbering around 2,400-3,800 inhabitants. Although by then it had been fortified, initially these were only wood and earth fortifications. It ceased to be sufficient when the threat from Irish pirates increased in the 3rd century, and military restructuring led to the withdrawal of the 2nd Augustan Legion from the fort at nearby Isca Augusta. These events initiated the expansion of the town’s fortifications, which were transformed into stone ones at the turn of the 3rd and 4th centuries. The final stage of the expansion of the fortifications was the reinforcement of the wall with a system of towers just before the middle of the 4th century.

In the first half of the 4th century, the town experienced a period of prosperity, which was reflected in the large number of newly built houses and their abundant decoration. However, the end of prosperity was brought about by the withdrawal of Roman legions from Britain at the end of the 4th century, relocated to fight in other parts of the empire. The town probably began to decline at that time, although it was still partially inhabited. Over the next hundred years, it languished, deprived of specialists who could take care of public buildings, fortifications and temples. The decline of trade and numerous invasions led to a decline in population and a lack of funds needed for renovations of the town’s buildings. It was not until the beginning of the 6th century that the town was partially reborn as the capital of the early medieval Welsh kingdom of Gwent. It was then that the Celtic name for the town Caerwent was developed, a combination of the word for stronghold and a corruption of the first part of the Latin name Venta Silurium.

The Norman invasion of England in 1066 was followed by a period of raids on Wales, both by the king himself and by earls from the border marches. The main Norman castles at this time were at Chepstow and Cardiff, while Caerwent was important only because of its location on the road between them. To ensure control of the route, a small motte castle was built at the south-eastern corner of the Roman fortifications. This castle, which was never more than a small watchtower, probably functioned for only a short time. As Chepstow became the dominant port in the region, Caerwent was transformed into a small agricultural settlement, with most of the former Roman town now used as pasture. In the first half of the 16th century there were only sixteen or seventeen houses among the Roman ruins.

Architecture

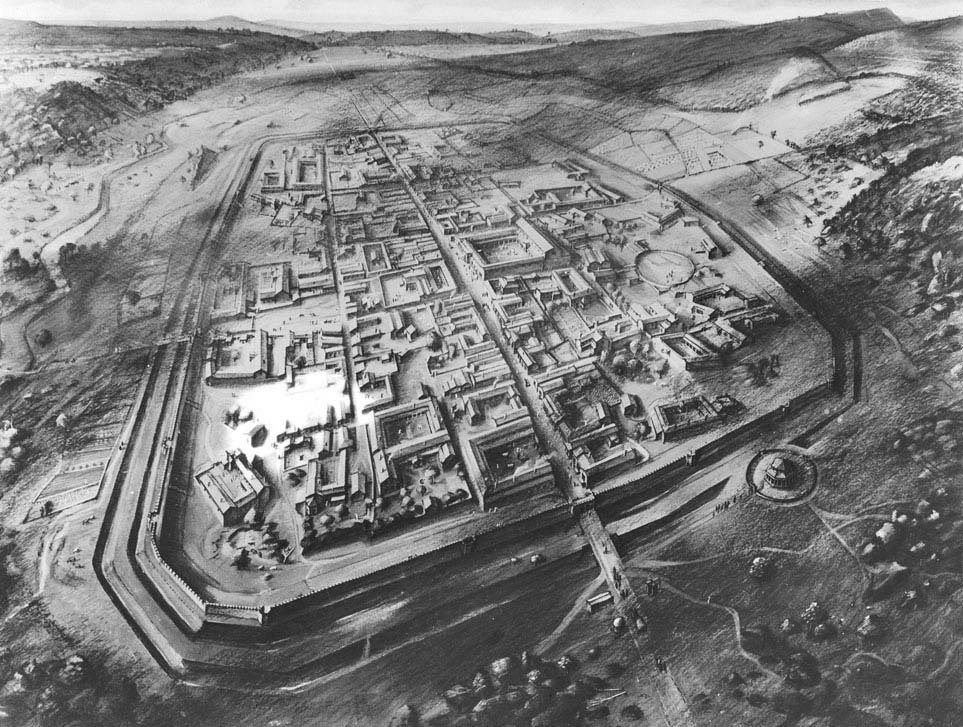

Initially, Venta Silurium was a small settlement with a dozen or so wooden houses scattered on the northern side of the Nedern River, along the road from Glevum to the Roman fort on the site of later Cardiff. In its final form, it was a large urban organism for Wales, covering 17.5 hectares, although on the scale of Roman cities in Britain, one of the smaller. It was founded on a plan close to a rectangle, with a truncated north-eastern corner and perhaps also the south-eastern corner, and with longitudinal sections slightly bent about halfway along, which could have resulted from the need to adapt to the terrain. The interior of Venta Silurium was covered with a regular layout of streets, which allowed the town to be divided into twenty quadrangular plots (Latin: insulae). The most important was the road running on the east-west axis, placed on the line of the main trade and communication route, on the sides of which two more streets ran parallel, and four crossed it at regular intervals. In terms of the buildings, Venta Silurium was essentially a miniature version of Rome and other major Roman cities, equipped with all types of public, religious and administrative buildings.

The first town fortifications consisted of a V-shaped ditch and an earth rampart. The latter was made of earth excavated during the digging of the ditch and reinforced with wooden poles for stability. It was topped by a palisade, behind which there was probably a wall-walk for the defenders. The rampart was 9 metres wide at the base and over 1.8 metres high. There were four gates leading into the town, one on each cardinal side of the world. The eastern and western gates, which were the outlets of the main street, were located in the middle of the fortifications in their sections, while the northern and southern ones were placed irregularly. This probably resulted from the existence of a previously established network of roads and buildings, centred around the forum.

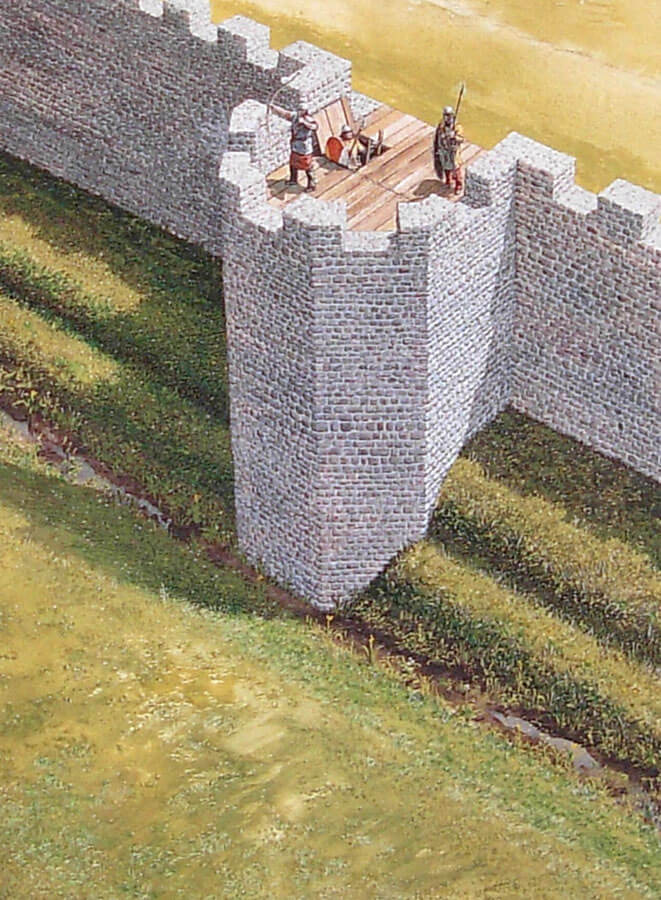

The stone fortifications built at the turn of the 3rd and 4th centuries consisted of a wall 7-7.5 meters high, of which at least 2 meters was a battlemented parapet. The wall was 3 meters thick at the base, but because of the offsets on the inner side of the perimeter, the width narrowed at the top to about 2 meters, which was still enough to accommodate a wall-walk for the defenders. The outer part of the wall, apart from a slightly widened batter, was roughly vertical. On the inner side of the wall, at intervals of about 60 meters, stone projections of full thickness to the very top were placed instead of a series of offsets. It were not intended to strengthen the wall structure, but were probably connected to the wooden stairs leading to the walk in the crown of the wall, or were its widening to allow for the placement of a ballista. Since the stone fortifications were in front of the old rampart, a new, second ditch was dug along the entire perimeter to take into account the increased height advantage that the defenders had from the new fortifications. The inner ditch was located 1.5 meters from the wall and was separated from the outer ditch by a flat area 8-9 meters wide. The outer ditch had a U-shaped cross-section, 7.3 meters wide and 1.8 meters deep.

About fifty years after its construction, the defensive wall was reinforced with a series of pentagonal towers with a maximum width of 8.2 meters, projecting in front of the defensive wall face by about 4.7 meters. It were partially opened from the town side, probably two-storey, with wooden platforms for defenders on the highest level. It were probably equipped with battlements together with the wall. Its lowest storeys served as a warehouse without external lighting, accessible only from the level of the upper storey. For unknown reasons, the towers were added only on the northern and southern sides of the town. Six were built from the south, five on the north, in both directions at not very equal distances from each other and not symmetrically with respect to the plan of Venta Silurum. Theoretically more endangered, eastern and western sections facing the main communication route were left without towers, perhaps due to their shorter length. In the south, the construction of towers may have been connected with the Nedern River, which in Roman times may have been navigable and approached closer to the fortifications, thus posing a risk of exploitation by sea robbers.

The four gates to the town were also converted to stone ones, along with the construction of walls at the turn of the 3rd and 4th centuries. The main entrances from the east and west consisted of two quadrangular towers flanking the passages located between them. In order to facilitate traffic, each of these gates was most probably equipped with two passages, located one next to the other. The towers at the gates were protruding in front of the neighbouring curtains on both sides, but to a much greater extent from the foreground side than from the town side. The height of the towers probably did not exceed the crown of the defensive wall by much. Their interiors at the first floor level were most likely connected with the wall-walk at the top of the curtains, in order to ensure uninterrupted communication, especially with the short sections located directly above the passages. The tops of the towers could had the form of open flat combat platforms, while the unlit ground floors could have served as storage rooms or guard rooms.

The less important northern and southern gates contained only one passage each, which was not flanked by towers, but could itself have a tower form. The southern gate protruded in front of the neighbouring curtains on both sides, significantly at the front and less at the back, while the front of the northern gate was in line with the defensive wall, and its projection at the back was significant. Both gates had passages about 3 metres wide, archivolts closed in a semicircular manner and set on massive impost cornices, and the interiors covered with wooden ceilings. The gates had double-leaf doors and had to be high enough to completely close the arched opening. The rotation of the gates was ensured by pins set in stone sockets in the threshold, as well as in upper sockets in stone corbels or in a solid crossbeam, in both cases above the level of the arch. On the first floor there could be a roofed guard room, connected to the wall-walk in the crown of the curtains. Towards the end of the town’s existence, the side gates were bricked up, only in order to maintain communication small pedestrian posterns were created.

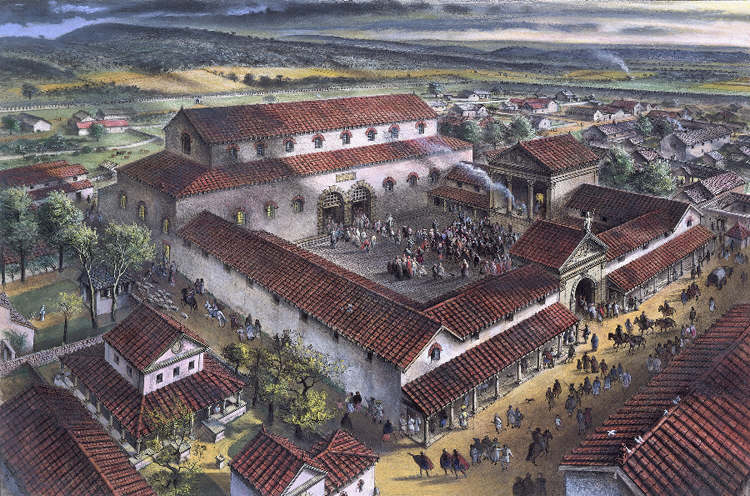

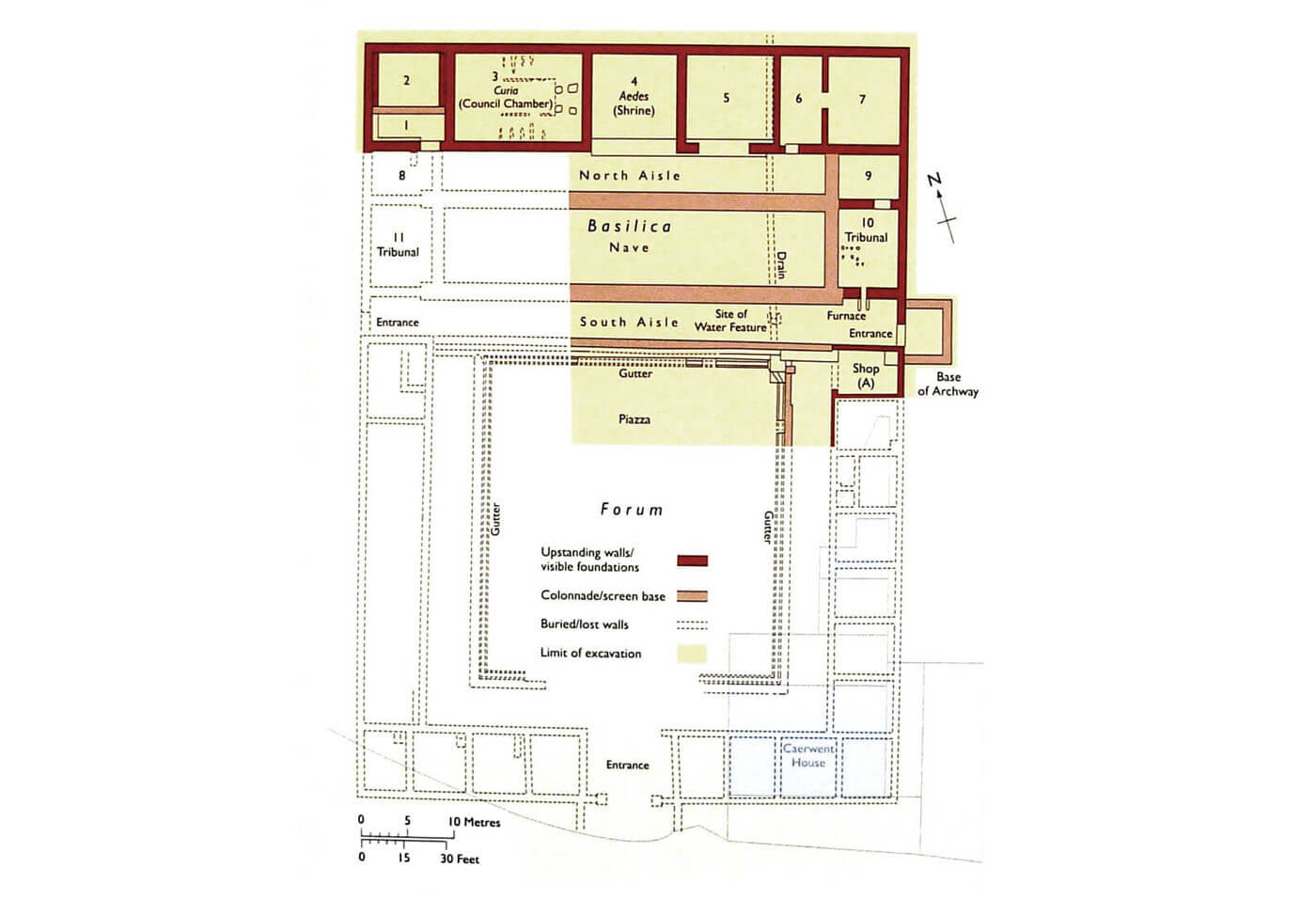

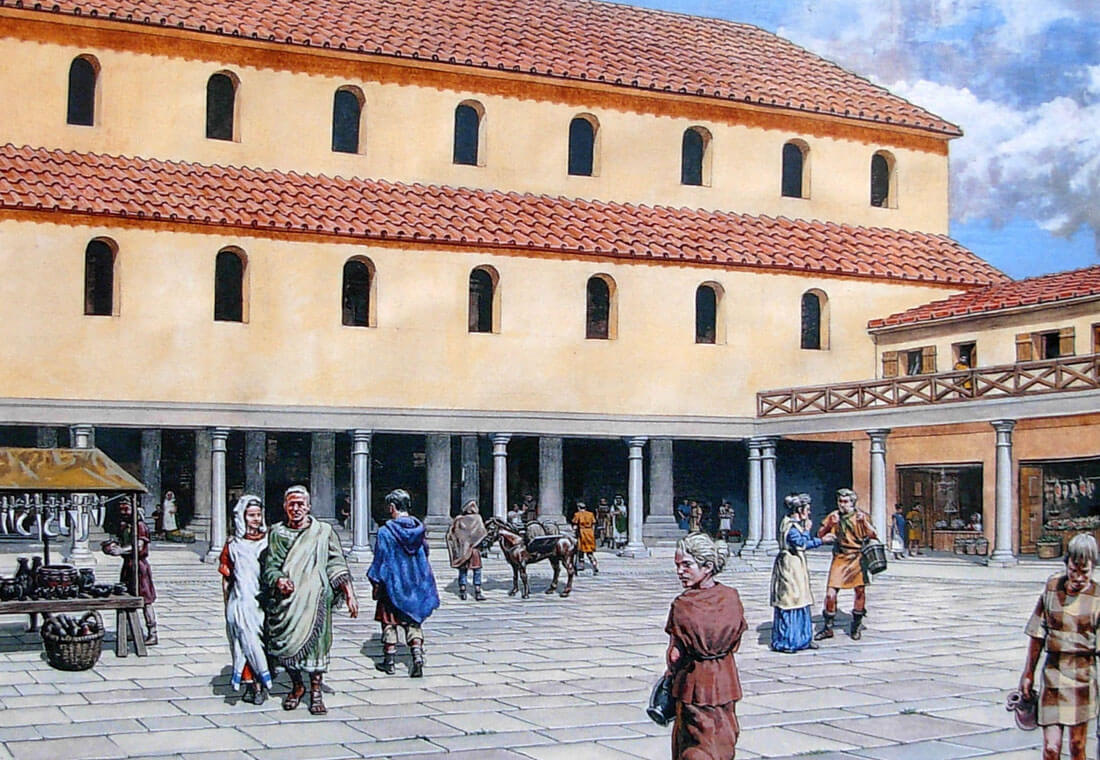

In the centre of the Venta Silurium was the forum with adjacent basilica, facing the main road through the town. The forum was an open market surrounded by porticoes with rows of columns supporting a roof shading the shops, offices and taverns, while the paved central area provided space for stalls. On the ground floor, each shop consisted of a single room with a large open front, probably closed with wooden shutters. These filled in particular the eastern and southern wings, on either side of the gate, while the western wing contained a single, elongated hall with a small room for officials at the northern end. The entrance to the forum was from the south, from the main street, through an arcaded gateway.

The basilica occupied the northern side of the forum. It was a large, aisled building measuring 80 x 55 metres and probably about 20 metres high to the level of the roof ridge, where the courts, the most important town events and festivities took place. The basilica faced the forum with a portico supported by a row of Corinthian columns. The interior of the basilica was also divided into aisles by Corinthian columns over 9 meters high: a wide central one and narrower side aisles. At the ends of the central nave were rooms called tribunals, intended for officials who listened to the cases of residents. The eastern one was later equipped with furnace heating. In the northern part of the basilica, a row of administrative rooms was separated, the largest of which served as the curia, or council chamber. This room had a floor covered with mosaic tiles and walls plastered in colors. Grooves were created in the floor, carved for wooden benches for those in session. A unique element for Britain were the stone bases for a wooden dais for officials. The council chamber was adjacent to a slightly smaller temple on a square plan, probably equipped with a bust of the emperor and a figure of a local deity. A canal ran along the entire width of the basilica beneath the building, collecting excess rainwater from the gutters. It was covered by massive slabs of sandstone weighing almost one ton, on which more decorative tiles were laid. At the southern aisle, by the canal there was a water cistern.

In the late 3rd century, the basilica underwent significant reconstruction. The roof over the aisles was dismantled and the columns between the aisles were removed. Some of the walls were reinforced, while the level of the floors was raised, probably because of the building subsidence or rotting of the wooden elements. It is likely that the purpose of the building changed at that time. It ceased to serve the town meetings and ceremonies that took place in the central nave and two side aisles, because in their connected interior there were several hearths, indicating that metal was smelted from then on. The smaller rooms may have continued to serve commercial or judicial purposes until the building was abandoned around the middle of the 4th century.

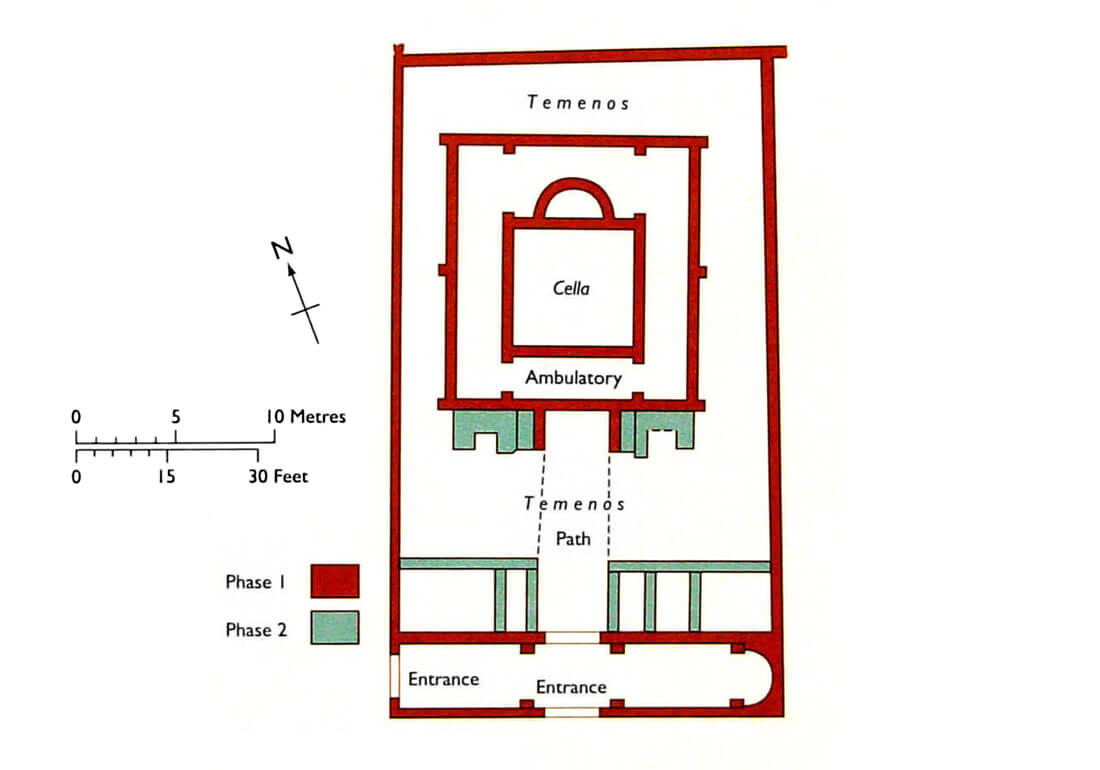

Not far from the forum, on the eastern side there was a Roman-Celtic temple complex. It was built quite late, around 330, on the site of an earlier Celtic temple. It is not known which deities were worshipped there, it could have been the Roman Mars or the Celtic Ocelus, it is also possible that it was already used by Christians. The temple was built on a square plan, with an inner sanctuary (Latin: cella) with a structure similar to a tower and an apsidal niche at the back, which housed sculptures and other objects of worship. The temple was entered via a long path leading out onto the street, preceded by a vestibule in the form of an elongated building. Two entrances led to it from the outside, and inside in the eastern part there was a small room with an apsidal ending, perhaps another, smaller temple. The main sanctuary was surrounded by an ambulatory, perhaps intended for ceremonial processions, and a sacred courtyard (Greek: temnos). Later five rooms of unknown purpose were built on the inner side of the vestibule in the courtyard, and two vaulted niches, probably for statues, were added to the ambulatory wall.

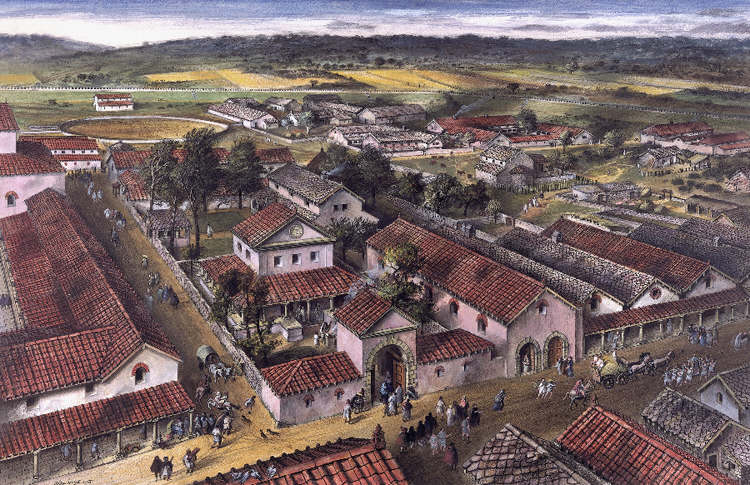

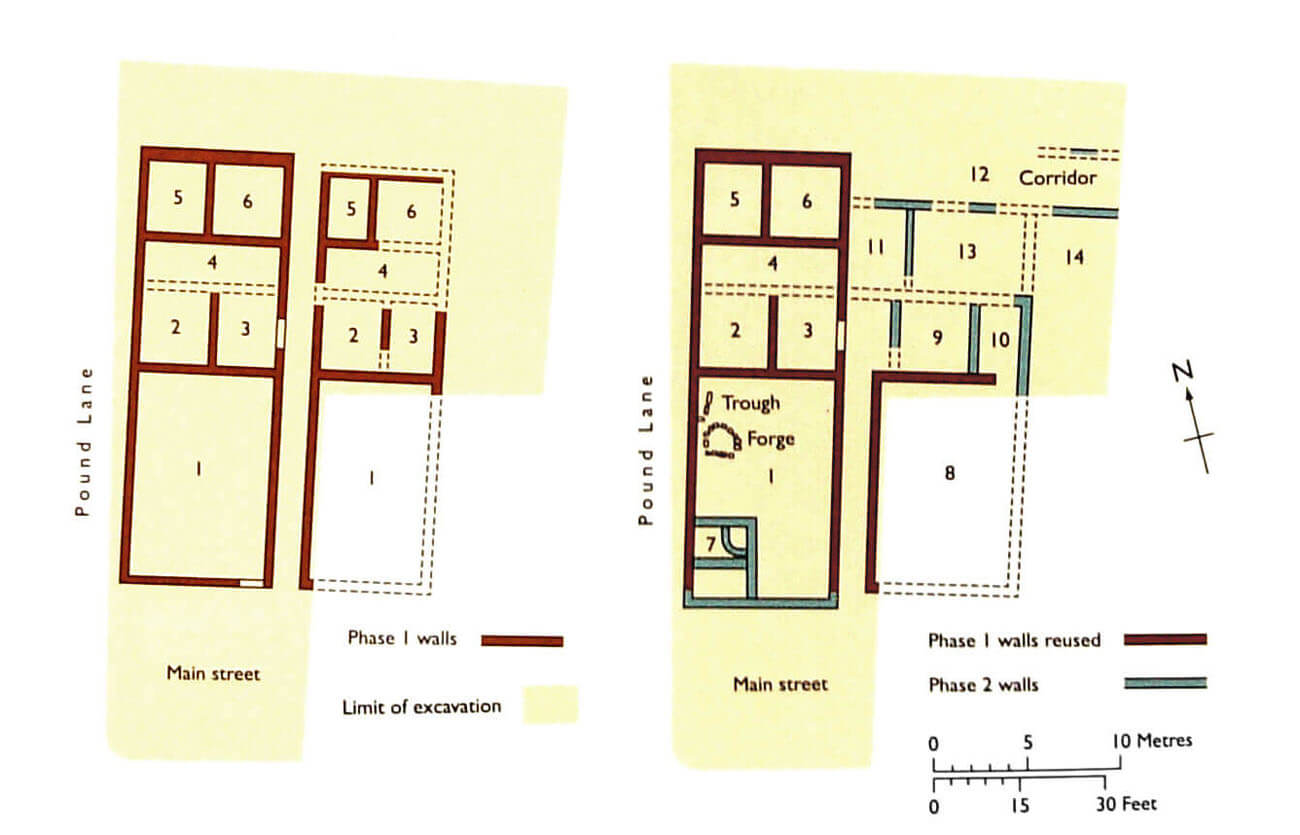

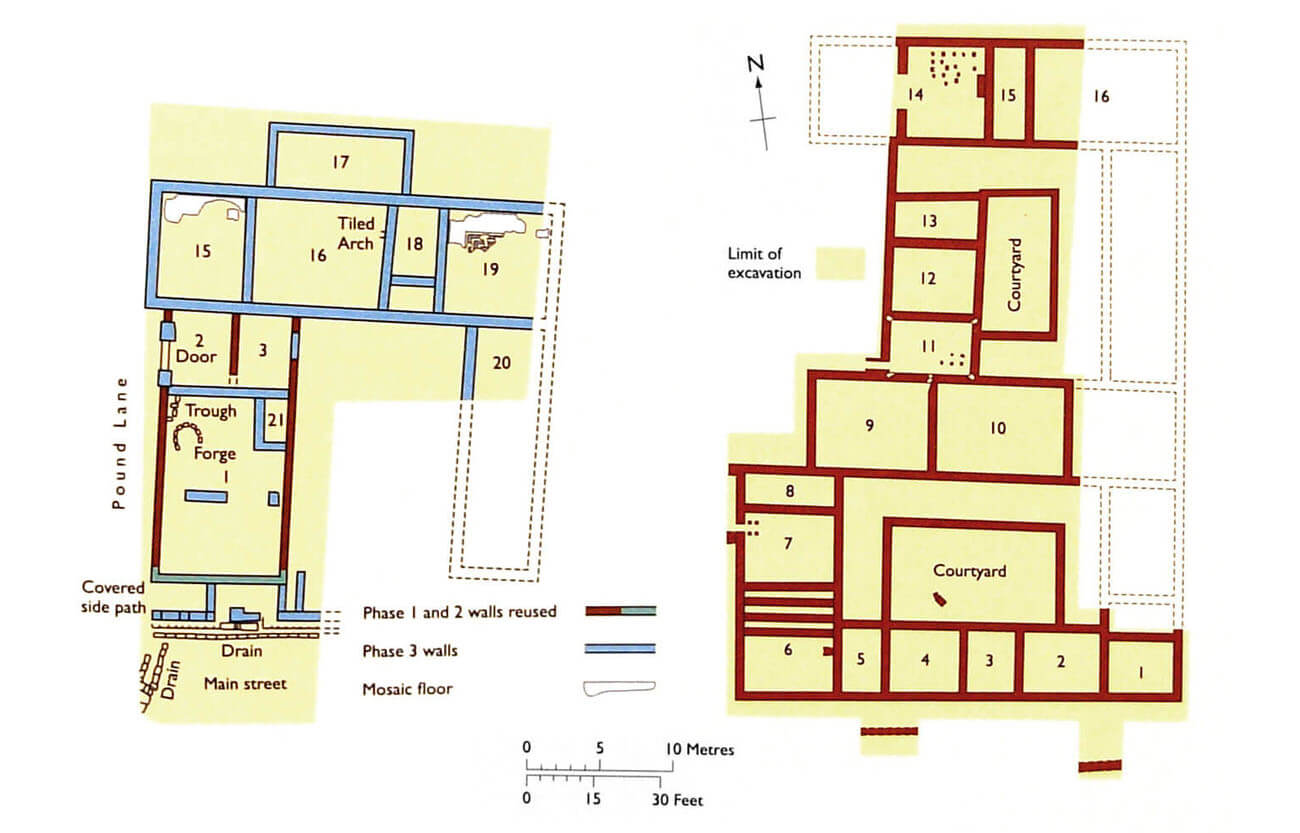

At the beginning of the 2nd century, public baths, shops and craft workshops were built, including a blacksmith’s forge. Shops were located mainly on the main street running through the town center from east to west. It combined a commercial function (the front part on the street side, closed with wooden shutters) with a residential function (the back and first floor of the building) and an economic function (the back of the house), where craft workshops were set up. Most of the individual shops occupied a single plot, separated by narrow passages. It provided a passage to the rear of the buildings, but more importantly it provided a gutter into which water from the roofs flowed. In at least one case, in the western part of the town, two connected shops were built, sharing a common portico, probably owned by the same owner. The baths were located on the main street, just opposite the forum.

The houses had the form of farms with small plots of land, but also developed, grand residences. The simplest were four-sided building blocks divided into a series of rooms accessible from corridors running along one or two edges. These passages ensured the privacy of the rooms, which would otherwise have to be directly connected to each other. The more developed houses consisted of two or more building blocks surrounding the inner courtyard, which could serve as a garden. Their layout could be spread, because beside the center, town provided enough free space for expansion. Rarely did a residential buildings had an upper floor, and only one basement was discovered. The windows were probably large to provide good interior lighting, some could be glazed, although Roman glass had a green – blue tint. Certainly they were secured with timber shutters or iron grilles. Inside the floor was compacted earth, perhaps sometimes the basis for wooden panels or tiles, but mosaics were often used in larger houses. Mostly they depicted geometric patterns, although there were also drawings of people or animals. Walls and ceilings were covered with plasters painted in bright and vivid colors. The popular way was to create colorful vertical stripes or bands. The main rooms in richer homes were heated with hypocaustum furnaces, others had to be equipped with portable braziers. Initially, the houses were erected in a half-timbered structure, i.e. with a wooden frame filled with wattle and daub, from the outside covered with plaster or whitewash to protect against moisture. Later, limestone and sandstone were used on a larger scale.

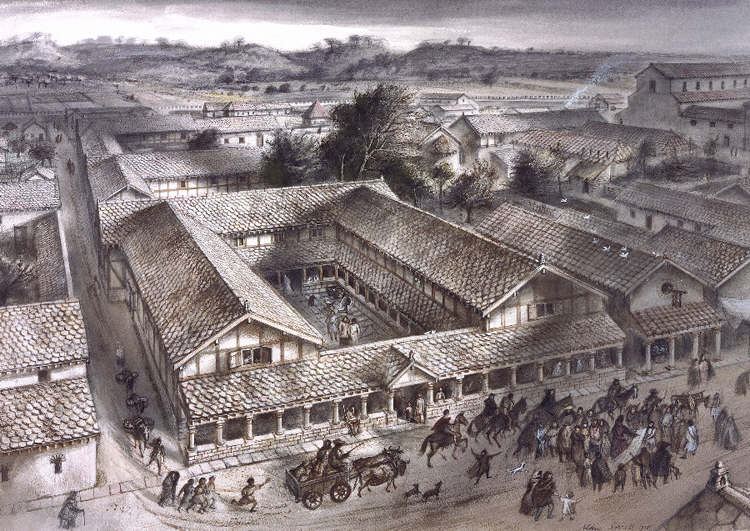

Another important public building was a mansio, a kind of inn, where couriers and oficials could rent rooms and exchange horses. In Venta Silurium, a large building in the southern part of the town, next to one of the main entrance gates, is identified as mansio. It was a complex of rooms grouped from three sides around the courtyard, with the fourth side enclosed by a wall parallel to the town’s defensive wall. The large yard, where horses and carriages were probably unhitching, also stretched out in front of the building. Of the rooms, some were heated by hypocaustum furnaces (using hot air), a rich mosaic was also discovered in one, larger room on north-west side. The building in the corner of the courtyard housed latrines with drains on three sides and timber seats.

Venta Silurium was provided with a sewage system, with clean water brought by an aqueduct from the hills to the north. It was distributed throughout the town by a system of canals, most of which led to the forum, the baths, and a few larger houses. Used water was used to flush latrines and a few main canals. For domestic use, most of the inhabitants drew their water from wells. In addition, all the town’s main streets had their sides profiled to ensure the drainage of rainwater. All the roads were paved with compacted gravel.

Current state

Currently, Caerwent is one of the most famous archaeological sites in Wales, in which you can see, among others, the foundations of the Roman forum, basilica and a Romano-Celtic temple from the 3rd century. Relics of houses with preserved remains of the hypocaustum heating system are located in the northwestern part of the town, as well as the remains of shops and workshops located near the main street. Also worth seeing (described in a separate article) are the town fortifications. In the best condition they have survived in the southern and western parts of the former defensive circuit. In addition, in the porch of the medieval church of St. Tathan is an altar dedicated to Mars – Ocelus and a pillar with a Latin inscription of Paulinus, commander of the legion II Augustus from the time of Emperor Karakalla.

bibliography:

Brewer R., Caerwent Roman Town, Cardiff 2006.

Newman J., The buildings of Wales, Gwent/Monmouthshire, London 2000.

Symons S., Roman Wales, Stroud 2015.

Ward J., The Fortifications of Roman Caerwent, „Archaeologia Cambrensis”, 71/1916.