History

Before the English town of Caernarfon was built, the area was occupied by the Romans, who built a fort Segontium, and later by the Normans and the Welsh princes. In 1282 king Edward I for the second time during his reign invaded northern Wales, pushing opponents west of Montgomery and Chester. In 1283, the English king secured Caernarfon and the surrounding area and decided that it would become the center of the new county and the capital of the subordinate principality of North Wales, with a new castle and a walled town. The construction of the new, fortified center was to secure military achievements, but partly was a symbolic act, demonstrating the English power.

Town walls were built in the years 1283-1292 under the supervision of master James of Saint George (Jacques de Saint Georges), the chief architect of Edward in North Wales. To build them, huge numbers of workers were mobilized throughout England. They were gathered in Chester and then transported to Wales for every summer construction season. Work on the walls has progressed quickly, although at uneven stages. The cost of urban fortifications was about 3,500 pounds, which was a very large sum at that time.

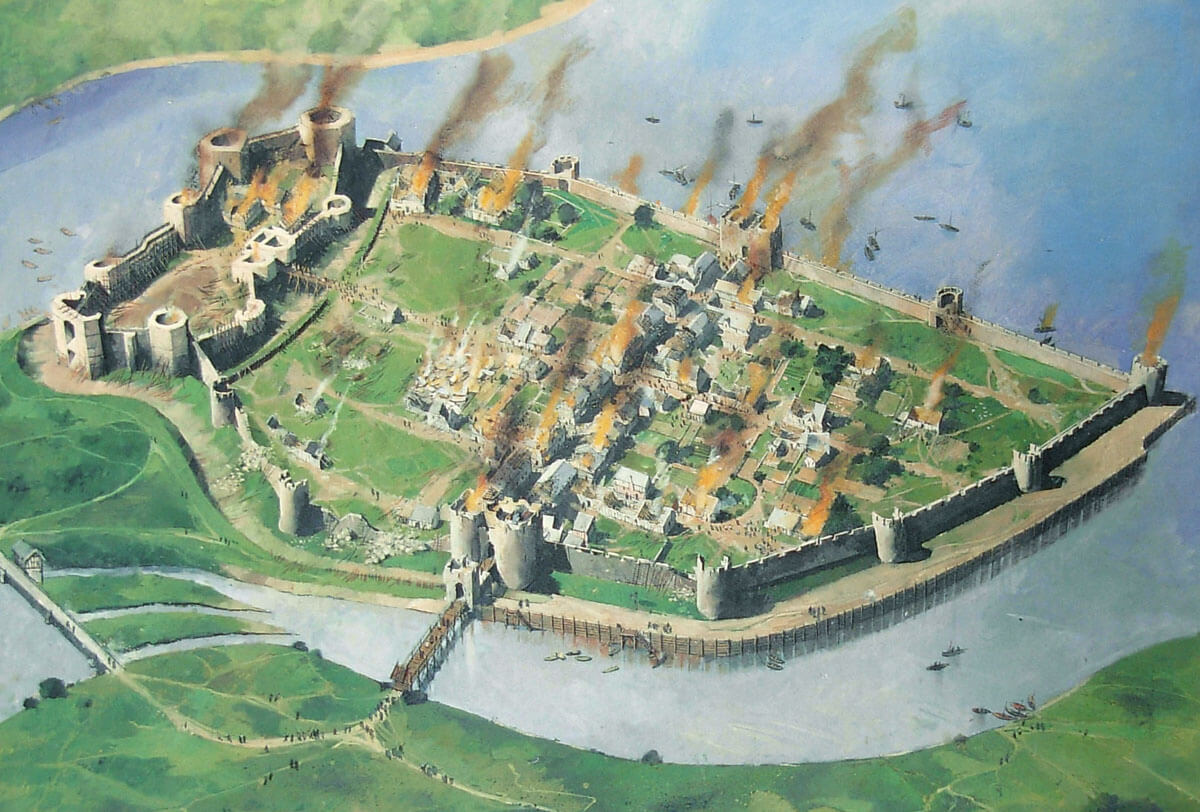

The baptism of fire of the town’s fortifications passed in 1294 during the Welsh uprising of Madog ap Llywelyn, which broke out due to the actions of the English administration, and in particular after the imposition of taxes, including one fifteenth of all movable property. The rebellion had been planned for months and attacks were to be launched on the same day across Wales. The rebel leaders hoped that at the end of September King Edward and most of his forces would be in France as part of the planned campaign, but due to bad weather, Edward’s army did not sail, and the ruler canceled the French campaign to deal with the Welsh uprising first. Caernarfon was one of the first English centers to be captured and burned, but a year later an English counteroffensive recaptured the town and the still unfinished castle. The damages were repaired immediately (the rebuilding of the town walls took 12 months and cost a £ 1000), while the insurgent forces were crushed on March 5 in the Battle of Maes Moydog. Although Madog managed to escape alive, he was captured after a few months and put in a London prison.

The new town was inhabited by English settlers, especially from the nearby Cheshire and Lancashire counties, and the town walls were partly intended to encourage immigrants and royal officials to settle in a safe place, but the urban population was not too high throughout the 14th century. However having fortifications came in handy in 1400, when Owain Glyndŵr, the last native Welshman to use a princely title, rebelled against English rule. Despite attempts to capture Caernarfon in 1403 and 1404, the townspeople repelled the attacks and saved their belongings (during the fights, among others, the foregate of the eastern gate was to be destroyed, repaired in the years 1406 – 1410). Only the ascension to the English throne of the Tudor dynasty brought the calming of the situation between the two nations. It changed the way Wales was managed. The Tudors were also of Welsh origin, which reduced the hostility between the two nations and the need to maintain the fortifications of the castle and the town. Eventually, since 1507 inside the town walls of Caernarfon, the Welsh were also allowed to live.

The town fortifications were repaired many times. Works on the towers were carried out between 1309 and 1312, after 1307 the church of St. Mary was built, which used one of the corner towers, and a little earlier, in 1301-1302 a bridge was rebuilt into a stone one in front of the eastern gate, and in 1304 a new mill and a dam at the mill pond were erected. After 1316, work was carried out on the conversion of a quays into a stone one, the sources also noted numerous works on the town walls near the castle, carried out in 1322, 1323 and 1327. A year earlier, the burned west gate had to be rebuilt, and the curtains at the castle and the gate were also raised. In the years 1406 – 1410 stonelayers and carpenters were employed to build a barbican at the bridge of the eastern gate, in 1434 – 1435 expenses were recorded for work on the chamber above the Water Gate, in 1507 the stone bridge was repaired, in 1516 – 1518 the drawbridge was renovated, and in 1520 the northern part of the town walls, reinforced with a buttress from the side of the moat. The quay at the town gate was to be repaired in 1525 and then in the period 1538-1539.

After the 17th-century civil war, the town’s fortifications were supposed to be demolished, but they still functioned with minor changes introduced in the 18th century. In the nineteenth century, the town of Caernarfon has grown considerably, some of the towers have been converted into administrative buildings, and rooms for offices were set up in the gatehouses. Small fragments were also demolished for the purpose of providing street traffic. As a result of the extension, many fragments of fortifications have been covered by houses and various annexes. It was only in the twentieth century that they were bought by the government and demolished.

Architecture

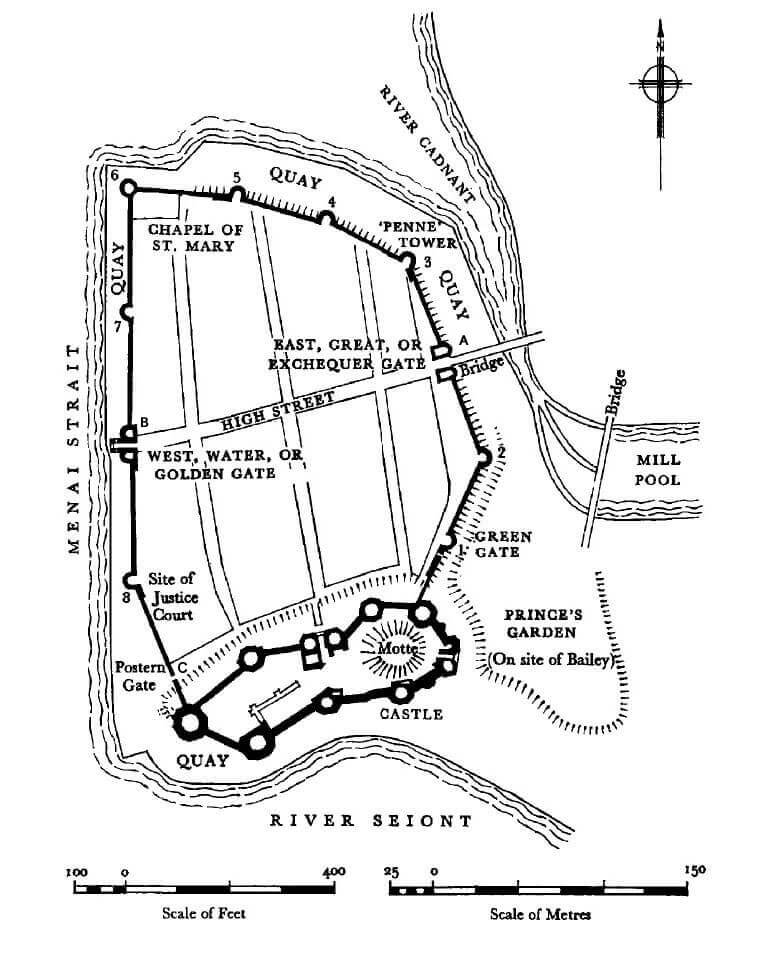

The town occupied a low, rocky peninsula cutting into the waters of the Menai Strait, that separates the main part of Wales from the island of Anglesey. From the south, the Seiont River ran around them, and from the north and east, the Cadnant River, on which bed in the form of a pond numerous water mills were located. Walls were built on a hexagon plan, the southern part of which was a castle. On the western side, the wall had a slight bend, the major bend was on the eastern side. The length of the fortifications was 734 meters and wall covered 4.18 hectares of the town’s area (approx. 250 x 200 meters). In the north-west corner of the walls was built the 14th-century church of St. Mary, who used the corner, round tower in the walls, as the sacristy and the house of the vicar.

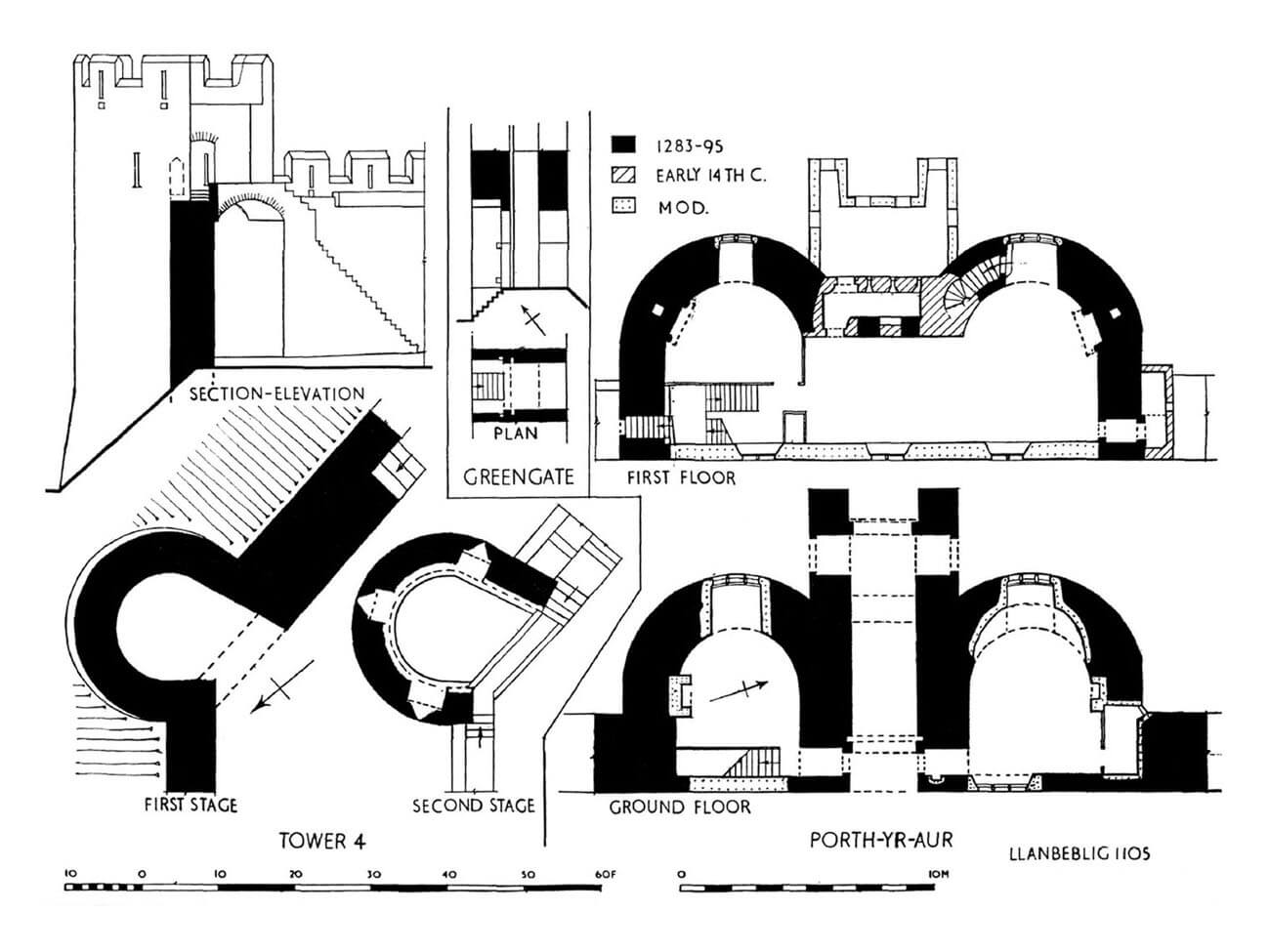

Curtain of the defensive wall, like the castle, were mostly made of limestone. The wall was topped with a wall-walk for defenders created entirely on the offset, without the need for wooden porches. A stone stairs led to it, added near each of the towers. The thickness of the wall in the ground floor was about 1.8 meters, the height was slightly more than 8.5 meters, with the wall-walk at a height of 6.7 meters from the town side. The protection of the defenders was provided by a parapet with battlement. The length of the merlons was about 2.7 meters, and the gaps between them were 1.1 meters. They were pierced with splayed arrowslits. Small holes pierced in the breastwork would indicate that in times of danger it was possible to erect wooden porches of hoarding at the curtains.

The wall was reinforced with seven semi-circular towers, open from the town side and one cylindrical, closed, in the north-west corner. They were placed around the perimeter relatively regularl, at intervals of about 68 meters. Towers were fully extended in front of the face of the defensive walls, with good conditions for side firing of the threatened curtains from which they were higher by about 3.6 meters. They consisted of two floors and an open, unroofed combat level, accessed through stone or wooden stairs from the level of the wall-walk of the curtains. Originally, they were equipped with removable wooden bridges in the rear parts to allow the fragments of the walls to be cut off before the attackers. The middle floors were equipped with three arrowslits arranged radially, while the lowest ground floor usually did not have any openings from the foreground side and was used only for storage purposes, if the rear parts of the towers were closed with timber work.

Among the towers, the closed (full) corner north-west tower, adjacent to the church from the beginning of the fourteenth century, was distinguished by its form. It was 9 meters in diameter. At the level of the lower floor, it housed a sacristy, and on the upper floor, a living room heated by a fireplace, probably used by the parish priest. Access to the upper floor was provided by stairs in the thickness of the wall, accessible from the northern aisle of the church, opened on the first floor to the vestibule with a small, two-light window, originally closed with wooden shutters and equipped with side seats. The main room of the tower’s upper floor was also connected with the wall-walk in the curtain’s crown and with the eastern small chamber, probably originally housing a overhanging latrine.

Two gates led to the town: the western one called Golden or Water Gate and the eastern one called the Great or Exchequer Gate. Both consisted of double, half-round towers protecting the passage between them. Originally it were closed with portcullis and doors, the eastern gate was additionally secured with a drawbridge and a battlemented foregate. The eastern gate has been housing rooms for officials since its inception. First, the royal exchequer room was arranged there, later, in early modern times the town hall and then the guild house. In 1301, a stone, four or five-span bridge, at least 45 meters long and less than 4 meters wide, was erected over the river in front of its foregate, at which fees were collected from merchants. The west gate had a central, four-sided part between the towers protruding towards the quay. In the ground floor, it housed a vaulted gate passage, and a living room on the first floor. Fireplaces were also created in the neighboring gate towers, despite the fact that their backs were closed only with timber works. Hygiene was provided by a latrine located at the northern tower.

In the south-eastern part of the perimeter, in the curtain between the north-eastern tower of the castle and the town tower, communication was facilitated by a postern called the Green Gate, probably leading to the area of suburban gardens in the vicinity or on the site of the original outer bailey. It was a passage pierced through the wall, ended with a pointed portal, closed with a portcullis and a door blocked with a bar. The second postern gate, until the church was built, functioned on the north-west side, later its portal was built into the nave of the temple. The third postern gate was at the castle on the south-west side of the town walls. Probably originally it was supposed to be a more developed water gate, used to supply the castle directly by boats through the wickets in the Well and Eagle towers.

The outer zone of defense was a dry moat from the north and east. Additional protection was the Menai Strait from the west and the Cadnant River from the north and east. The southern part of the town was protected only by the royal castle, to which the town was opened, so it did not have its own stone fortifications on its side. This two centers were separated only by a moat. A waterfront (quay) was created in front of the defensive walls on the west side, originally timber, but after burning in 1294, it was rebuilt with stone at the beginning of the 14th century.

Current state

The medieval fortifications of Caernarfon are currently one of the best preserved, not only in Wales but throughout Europe. The defensive circuit survived practically at the entire length, only the crowning of some towers, gates and walls has not survived, in several places, modern passages were pierced to facilitate communication and some sections were rebuilt in the early modern period (e.g. the curtain between tower no. 2 and the eastern gate). Tower No. 4 is considered the best-preserved, visible in its entirety up to the battlement level, as well as the adjacent curtain connecting with tower No. 5. Because of great value, fortifications of Caernarfon were added to the UNESCO World Heritage List.

show northern part of the fortifications on map

show eastern part of the fortifications on map

bibliography:

Haslam R., Orbach J., Voelcker A., The buildings of Wales, Gwynedd, London 2009.

Kenyon J., The medieval castles of Wales, Cardiff 2010.

Salter M., Medieval walled towns, Malvern 2013.

Taylor A. J., Caernarfon Castle, Cardiff 2004.

The Royal Commission on The Ancient and Historical Monuments and Constructions in Wales and Monmouthshire. An Inventory of the Ancient and Historical Monuments in Caernarvonshire, volume II: central, the Cantref of Arfon and the Commote of Eifionydd, London 1960.