History

Caerleon Legionary Fort, called Isca Augusta or Isca Silurum in Roman times, was built around 75 AD. Its construction was related with the campaigns of the Britain’s governor, Julius Frontinus against the Celtic tribe of Silures, who occupied the lands of south-east Wales. This tribe resisted the Roman invasion for more than thirty years, inflicting several major defeats on the invaders. Frontinus changed strategy by deciding to build a fort deep in enemy territory, where it would be possible to defend itself effectively and at the same time pacify the natives. The place of the fortress was chosen because of its location on the gently rising terrain adjacent to the Usk River, which was accessible to sea-going vessels, and near the routes between Viroconium (Wroxeter), Glevum (Gloucester) and Moridunum (Carmarthen). Thanks to this, the ability to easily send supplies to Isca Augusta was secured.

The fort was the seat of II Augusa legion, a unit of about 5,500 men, along with accompanying staff and Roman residents. During this period, the legion was divided into cohorts, the first of which consisted of 800 legionaries, and the remaining four of 480, each divided into six centuries. The fortifications were used by II Augusta legionnaires until about 300 AD. Around 122, some of the fort’s buildings could be depopulated due to the construction of the great wall by Emperor Hadrian in northern Britain. For this reason, numerous craftsmen and bricklayers were drawn from all over the province, as well as troops to protect them. Roman tomb inscriptions found at Hadrian’s Wall confirm that there were also legionaries from the cohorts of II Augusta. In turn, when the emperor Commodus was murdered in 192 and the civil war broke out, the II Augusta legion went to Gaul to support the pretender Clodius Albinus, governor of Britain, proclaimed Roman emperor in 196–197. Finally, he suffered a defeat along with II Augusta at the Battle of Lugdunum.

At the beginning of the third century, after normalizing the political situation under the rule of Emperor Septimius Severus, Caerleon still served as the main seat of the II Augusta legion, although it is known that it was sent north to stabilize the Caledonian border. There were probably plans to permanently move the legion there, but eventually, after Severus’ death in 211 during an expedition in the north, Caracalla and his brother Geta made peace with the Caledonians, and Isca was thoroughly renovated for the legionaries brought home. The next involvement of the Caerleon legion was caused by internal fighting after the assassination of the emperors Alexander Severus in 235 and Gordian III in 244. During the absence of the army, the buildings, including baths and the amphitheater, were maintained by local staff and residents, however, the decayed barracks were renovated in 274 -275 during the more peaceful reign of Aurelian.

The fort’s end came in the years 287-293, when the usurper Carausius declared himself Roman emperor, supported by troops on the island. Expecting an invasion of Britain by the rightful rulers Diocletian and Constantius, Carausius began preparations for defense. As part of these, some of the fort’s buildings were dismantled, probably for use elsewhere. It was later partially inhabited, although it is not known whether by civilians or military units. Legion II Augusta was probably moved to Rutupiae (Richborough), so if any military units remained in Isca, it must have been minor auxiliary units. By the end of the 4th century, the Roman population of Isca had significantly declined, while a settlement of Celtic people eventually grew on the ruins of the Roman fort.

In the Middle Ages Caerleon was one of the administrative centres of the Kingdom of Gwent, and also had religious significance as an early bishopric associated with Saint Dubricius. A parish church was built on the site of the Roman fort and after the Anglo-Norman conquest in the second half of the 11th century a motte castle. During the Welsh-Norman fights of 1171, the Prince of Gwynllwg, Iorwerth ab Owain and his two sons destroyed the town, although they failed to capture the castle itself. In 1217 both the castle and the settlement were captured by William Marshall, who rebuilt the feudal stronghold. The remains of many of the old Roman buildings probably been preserved to some extent to this day, but were probably demolished to obtain building materials for the reconstruction of the castle.

Architecture

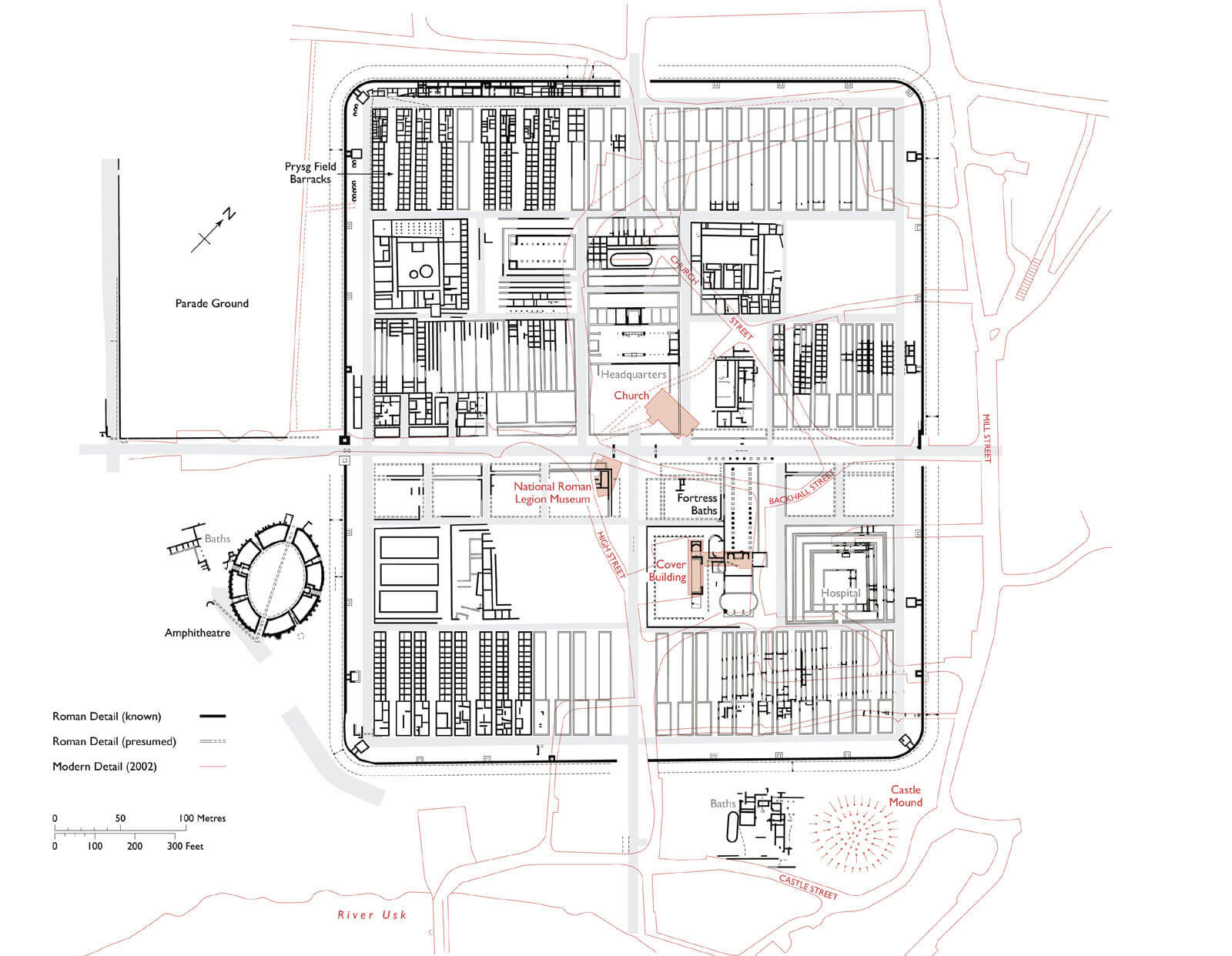

Isca was situated on a slight elevation in a wide bend of the Usk River, which provided protection from the south, and to a large extent from the west and east. To the north-east the fort was limited by the smaller Afon Lwyd river flowing into the Usk, while to the north-west by a latitudinally elongated hill. The fort covered an area of about 50 acres, with its longer axis on the north-west, south-east line. Outside its fortifications, there were wharves and fishing facilities on the river. The area in front of the gates was partially leveled (campus), probably to hold legionnaire parades, and a road was created to allow bypassing the fort without having to go through it. In time, a small civilian settlement (canabae) developed on this road and in front of the gates, with several baths, an amphitheater and probably several temples known from inscriptions (Diana, Jupiter, Mithra). A little further away, cemeteries were established on three roads leading to the fort.

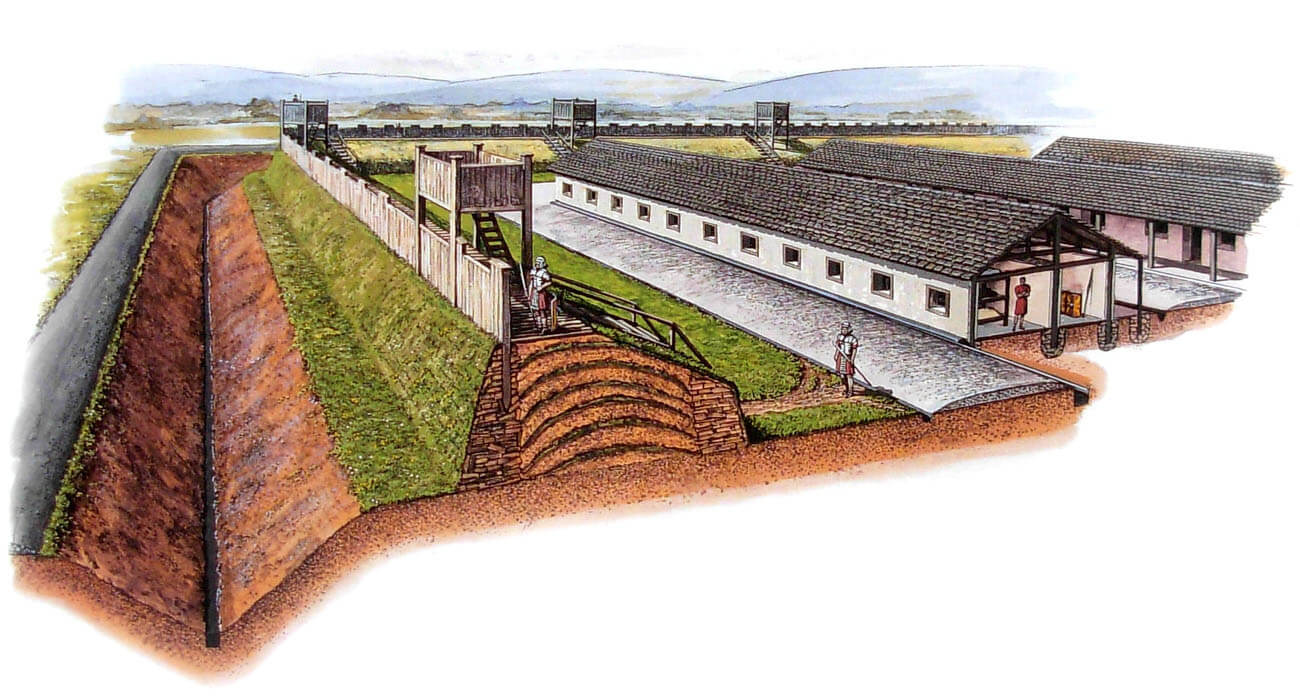

The earliest fortifications consisted of peat-clay ramparts topped with timber palisade. The fortifications were built on a rectangular plan with rounded corners, measuring 490 x 418 meters, with an entrance gate in the middle of each side. The fortifications were strengthened by twin wooden towers flanking all the gates and single wooden towers spaced at equal intervals in the perimeter of the fortress walls. The outer defense zone was a ditch with a V-shaped cross section, 8 meters wide and 2.5 meters deep, surrounding the entire fort. The rampart with vertical walls reinforced with oak piles was 5.5 meters wide and up to 3 meters high. There was a wall-walk on the inside of the rampart, allowing legionnaires to quickly access each endangered fragment.

At the beginning of the 2nd century AD the fortifications were rebuilt into stone ones. The outer part of the embankment received a stone wall 1.5 meters thick, and the gates were reinforced by twin stone towers. The remaining wooden towers were also replaced by a 30 stone, small quadrangular towers measuring 4.5 x 4.5 meters, spaced 43 meters apart and placed on the inside of the perimeter, so that their front walls were in line with the outer elevations of the curtain walls. Even the corner towers, placed on the arch of the wall, not at the curtain walls creating a right angle, were solved in this way. This made active defense with flanking fire on the base of the wall impossible, giving only a slight height advantage over the curtains adjacent to the towers. Each tower had two storeys, with the lower one being a basement inserted into the rampart and serving only as a warehouse. The upper storey was accessible through a door in the rear wall of the tower and connected with a wall-walk in the crown of the fortifications, led at the same height. Higher on each of the towers there had to be an open, unroofed observation and defense platform. Both the towers and the curtain walls had to be crowned with a breastwork to protect the defenders.

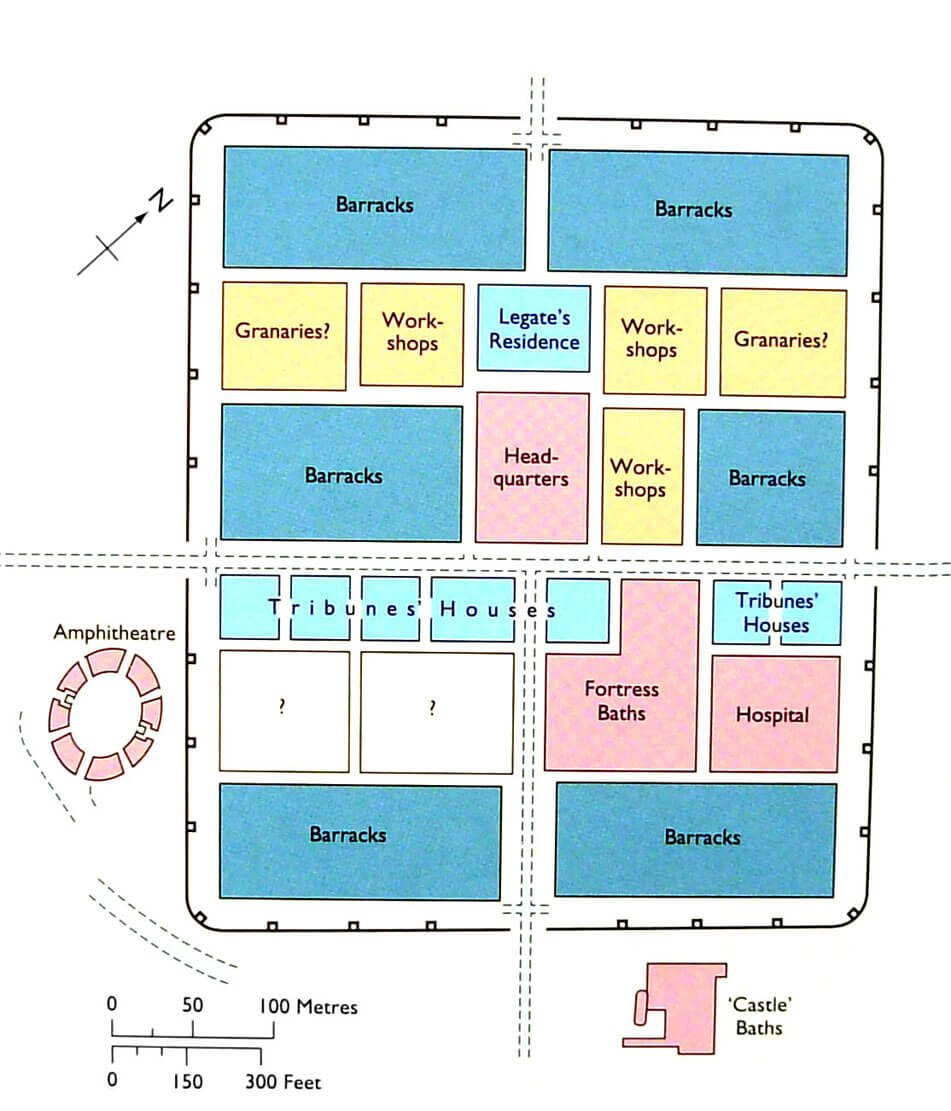

The internal layout of the Isca Augusta followed the standard plan of a legionary fort: from east to west the main road, the via principalis, 7.5 meters wide, ran through the entire complex, and from the south to the center of the complex, the equally wide via praetoria, connecting the gate with the principia, the legion’s headquarters. Its counterpart to the north was the shorter and narrower via decumana, connecting the gate with the legate’s residence, the praetorium. In addition, there was a network of other smaller, perpendicular and parallel roads connecting different areas of the fort, as well as the aforementioned underwall street, running along the fortifications. The two main arteries were solidly made of cobbles and clay, set on gravel and crushed stone. Both had side drains, with a bottom made of flat stones for easier maintenance. Both were also equipped with deep central sewers, in the case of the via principalis 0.5 meters wide and 1.3 meters deep, with a corbeled top buried under the road surface. The via decumana was of much more modest construction, without side or central sewers, which would indicate that it was less frequently used by traffic. The smaller streets differed in construction, but the more important ones were equipped with shallow drains.

The main streets divided the fort into five large plots – latera prateorii, filled with fairly regularly spaced buildings. In the centre was the headquarter, behind which to the north was the legate’s residence, and opposite, along the via principalis, a row of buildings for senior commanders. On either side of the headquarter and the legate’s residence were workshops designed for industrial-scale ironworking, also occupied by the legion’s craftsmen, among whom there must have been masons, blacksmiths, tanners, carpenters and shoemakers. The remaining spaces of the fort were filled primarily with legionnaires’ barracks. The earliest buildings were probably built of wood, later replaced with stone on exactly the same plan. It could have been half-timbered structures with vertical posts set directly in the ground or in load-bearing beams. The walls were filled with wattle, covered with clay and then with waterproof plaster. The internal elevations were probably occasionally painted in colours. The roofs were covered with well-burnt tiles and moulded terracotta ornaments on the gables. The floors were made of various materials: clay, gravel, concrete or planks. The windows were equipped with thickly cast panes, transmitting a subdued green-blue light.

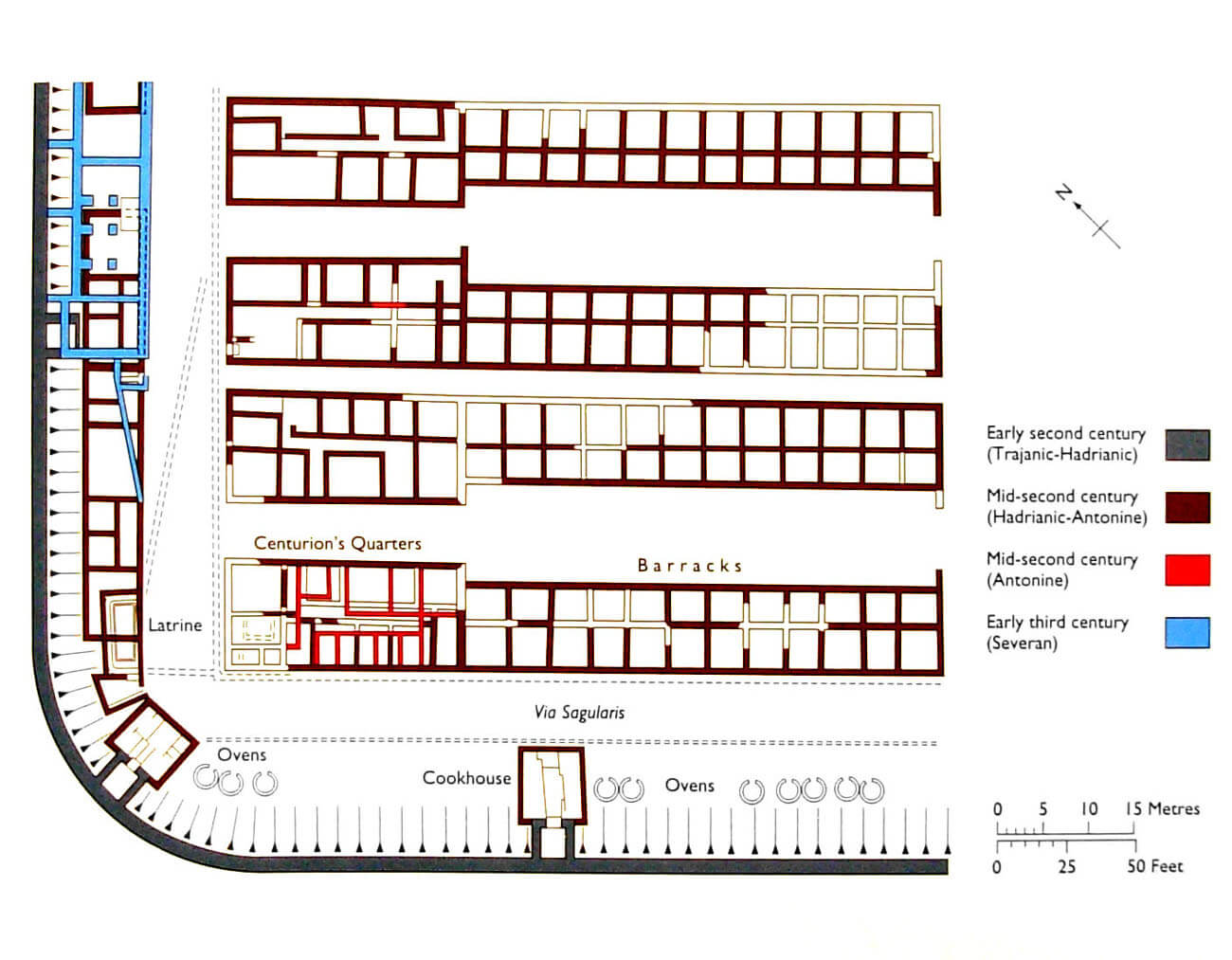

The legionnaires’ barracks were attached to the north and south sides of the fort and in the middle of the west and east curtains. It consisted of narrow blocks almost 74 meters long, about a third of which were allocated to centurions (this part was slightly wider than the quarters of ordinary legionaries). The blocks were arranged in pairs opposite each other, which may have reflected the old Republican division of legions into maniple or double centuria. At Caerleon, as in most other Roman forts, narrow passages were left between pairs of blocks. There must have been 60 barracks in total, since a single building could accommodate a centuria (80 men), with ten groups of eight men sharing two rooms (6 centuria equaling 480 men in a cohort). The smaller of the two rooms was used as a storeroom for weapons and equipment, the larger rooms measuring 4.3 x 4 meters were used as a bedroom. The centurions’ residences at the ends of each barracks block also included apartments for junior officers and rooms for officials. As they were wider, their interiors were in most cases divided by a central passage. The heating must have been in the form of portable stoves, as no traces of the hypocaust system or fireplaces have been found.

The latrine blocks since the 2nd century reconstruction were located directly next to the rampart, on the side of the shorter walls of the legionnaires’ barracks, while a series of stoves and kitchens were located to the south, also on the inner side of the fragment of the fortifications, separated from the barracks by the via sangularis. A single latrine block in the south-west part of the fort measured about 9 x 4 meters. A sewage channel with rounded corners and a stone bottom ran along three of its walls. Wooden seats were installed above the channel, and the floor was paved with stone slabs with a drain located close to the sewage channel. The wedge-shaped room between the latrine block and the corner kitchen served as an anteroom, but must also have contained a cistern for flushing.

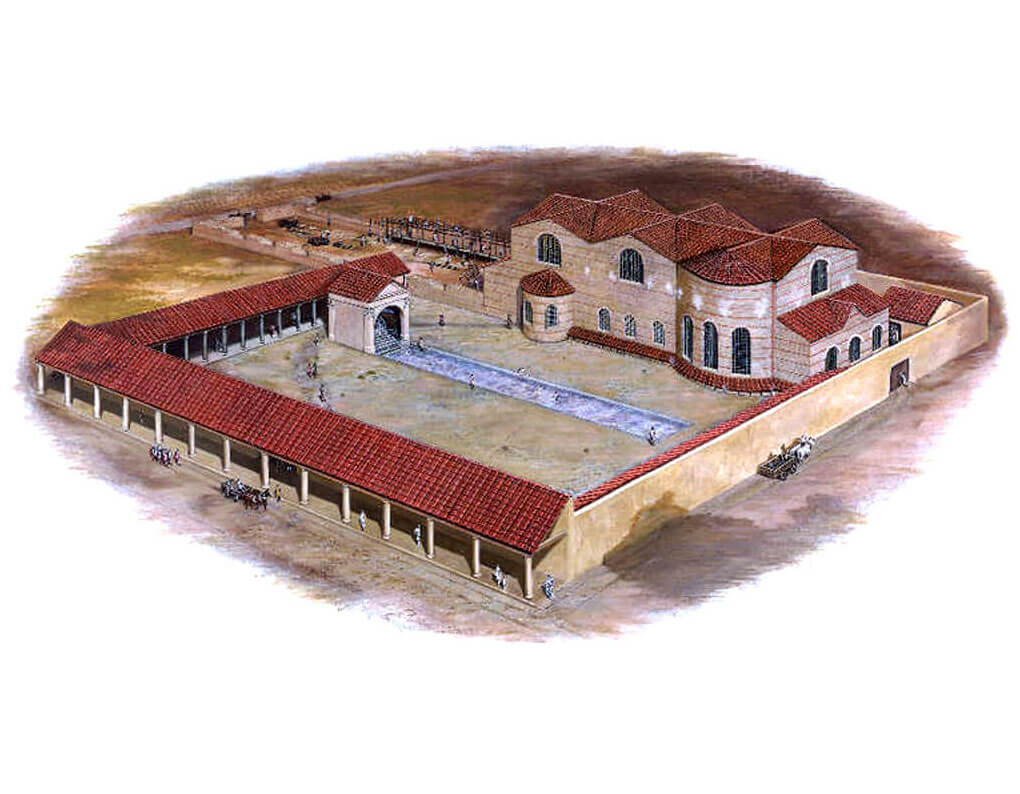

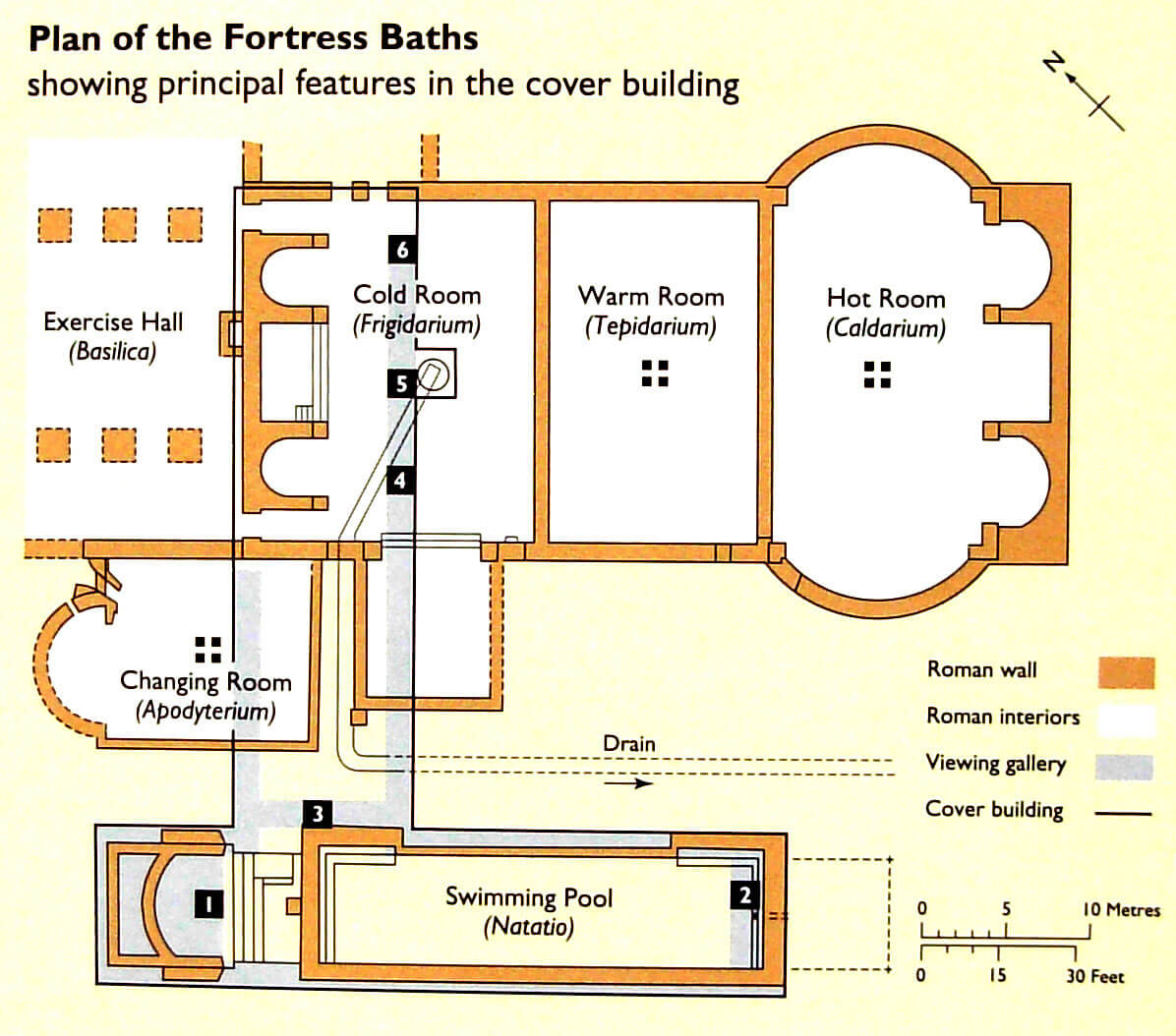

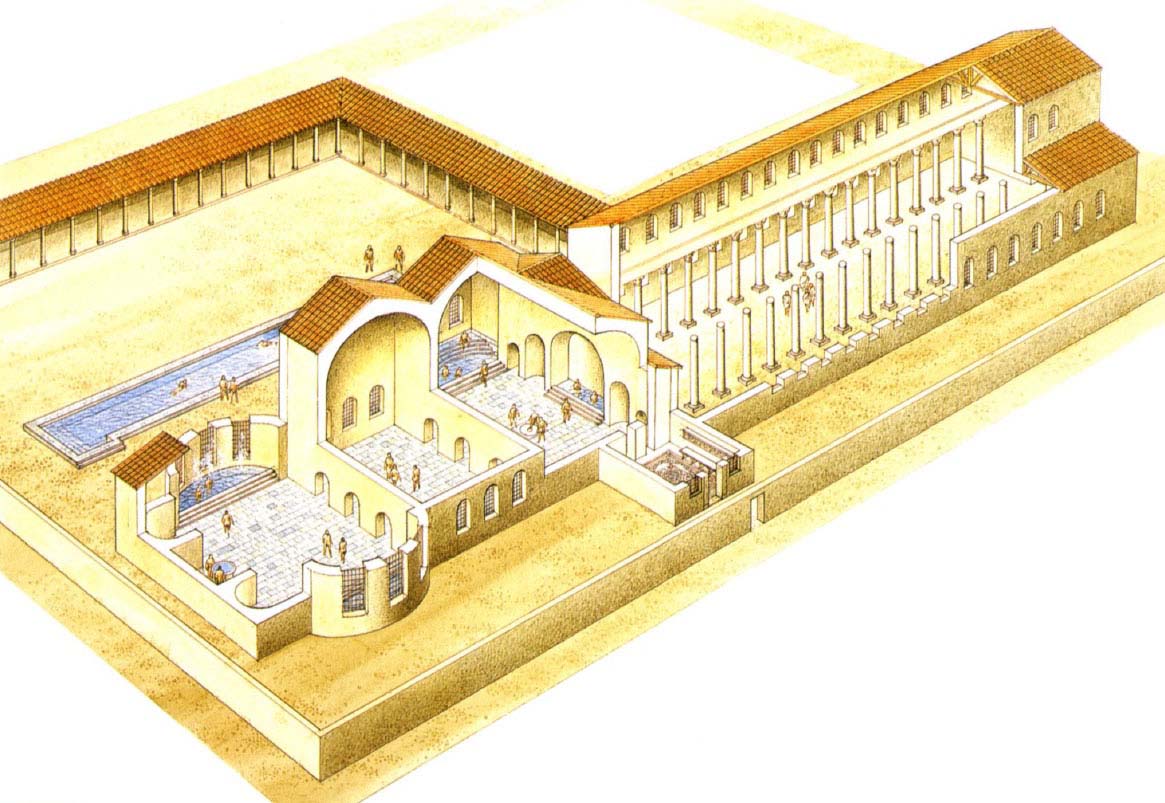

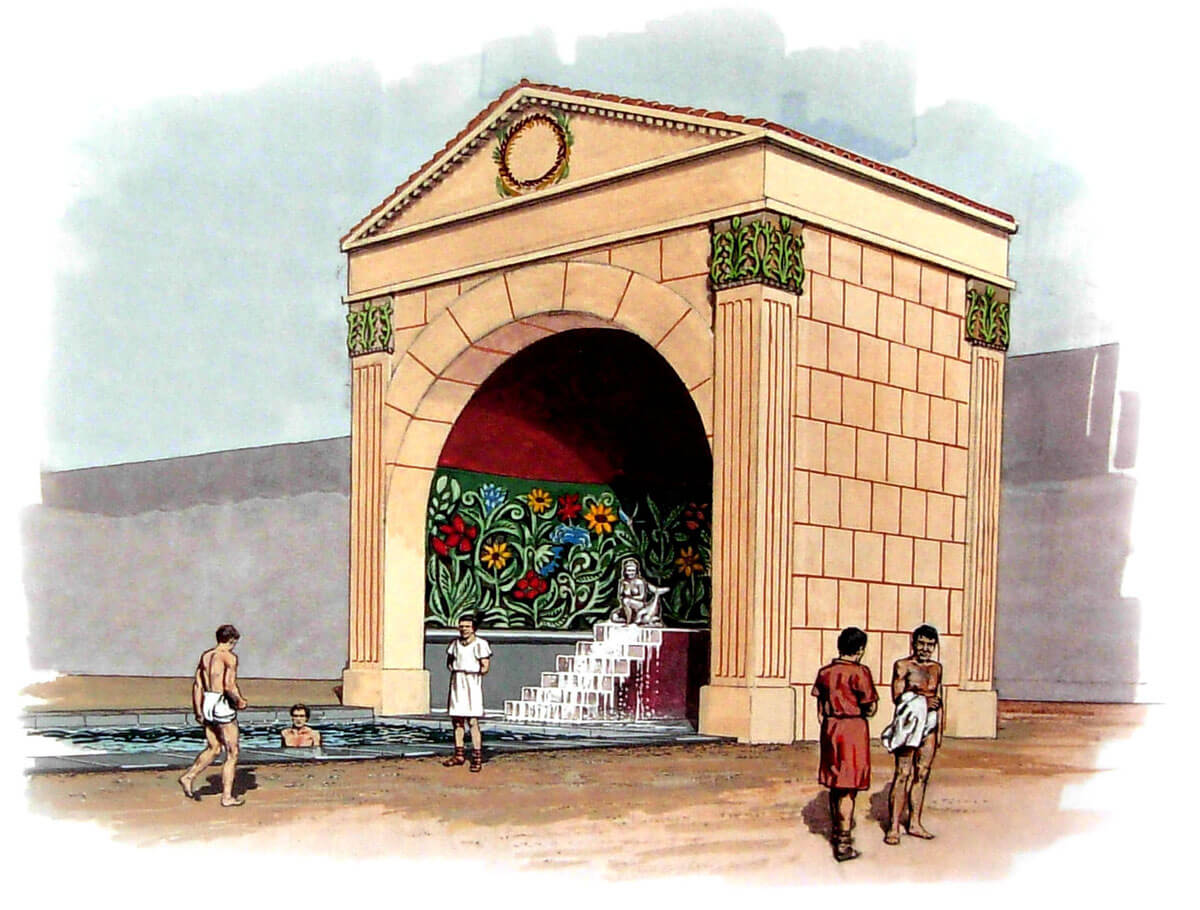

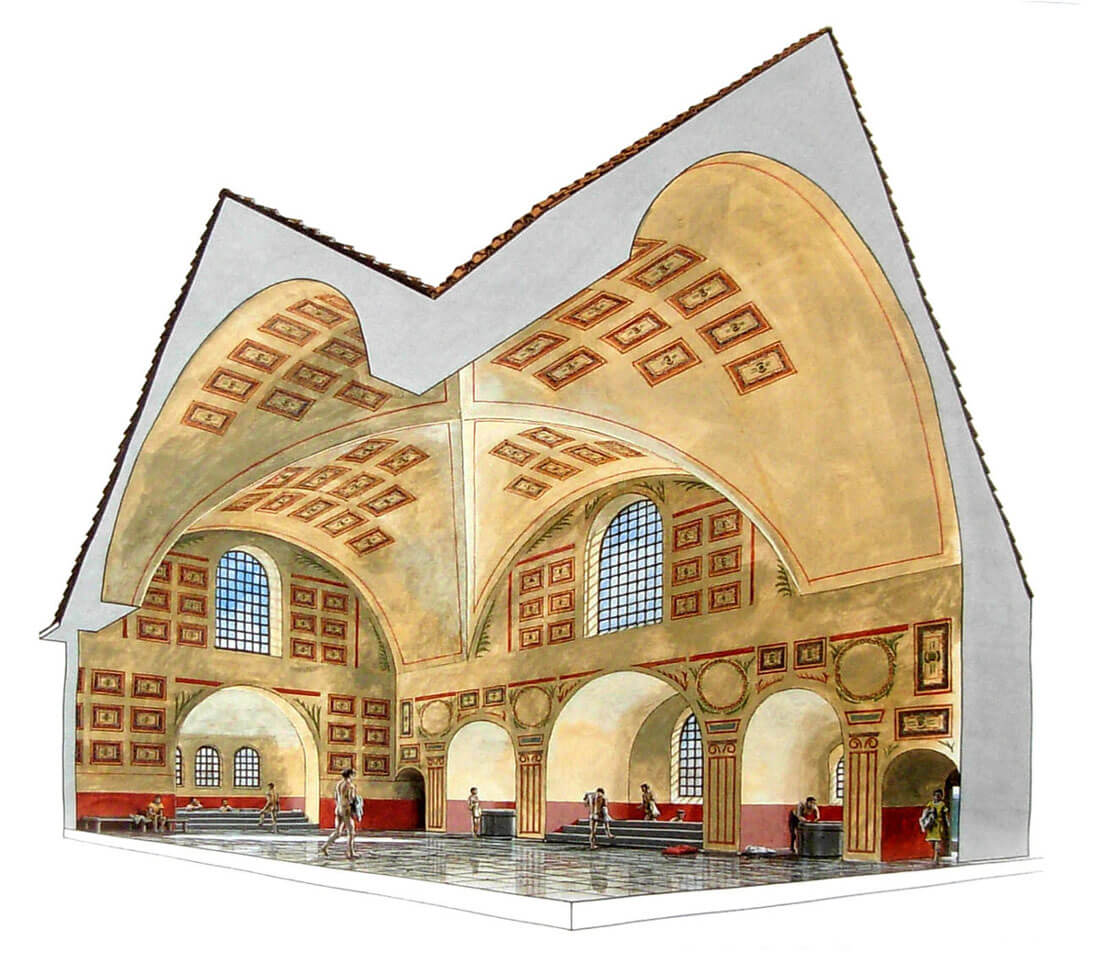

On the south side of the via principalis were the baths, one of the first buildings to be built in stone around 75 AD. It was a huge complex, 110 meters long, encompassing a large, open courtyard with a pool and a number of buildings containing baths. The courtyard, called the palaestra, was used for outdoor exercises and games. It measured 75 x 45 meters and was surrounded on three sides by a portico. At its northern end was a small building with an apse (nymphaeum), housing a fountain that fed water through lead pipes to an elongated pool (natatio), as long as 41 meters long and 6-7 meters wide, running through most of the courtyard. Water flowed down the steps from the fountain, probably coming from the mouth of a carved dolphin. The pool, 1.2 to 1.6 meters deep, held an impressive 365,000 liters of water. The main bathhouse consisted of three spacious halls: a cold bath (frigidarium), a warm bath (tepidarium) and a hot bath (caldarium), built of stone and topped with concrete vaults. On the north side, they were adjacent to an elongated building in the form of a basilica and a smaller room for a heated changing room (apodyterium), added around 150 AD.

The basilica, a covered exercise hall 64.5 meters long and 24 meters wide, was divided into a central nave 12 meters wide and two narrower side aisles. The division was made by means of two rows of brick piers, each consisting of 17 pillars. These pillars did not stand on continuous stereobates, as in the basilica principium, but on massive, single foundations topped with blocks of local yellow sandstone. The side aisles, and probably the main aisle as well, were spanned by barrel vaults. The floors were made of white and bluish limestone, laid on a gravel base. The frigidarium was entered from the basilica through two passages, placed on the sides of a pool flanked by two more apsidal basins. At one of the passages, in the south-west, the frigidarium ended with a large apsidal bath, lined with green sandstone, probably 11.5 meters wide. A large, although poorly bricked apse, probably housing a statue, was distinguished in the apodyterium, while wooden wardrobes were placed along its side walls. The construction of the hypocaust heating system meant that the south-west wall of the basilica was dismantled over a length of almost 8 meters. Probably, along with the apodyterium, a vestibule was also built at the south-eastern end of the basilica, because the removal of such a long wall must have had a serious impact on the building’s vault.

On both sides of the bath complex, facing the via principlais, were the aforementioned houses for the tribunes and other senior officers, while in the south-western corner of the fortress, behind the tribunes’ houses, there were three granaries and a large building with a courtyard, which served as a warehouse. Excavations have revealed that it was used to store military equipment. On the eastern side of the bath complex, there was most likely a hospital (valetudinarium) from the beginning of the 2nd century AD. The choice of its location was supposedly dictated by the need for silence for patients and the proximity of the baths. The building had the form of a double row of rooms separated by a long corridor, surrounding three sides of the large courtyard. On the fourth, southern side, a large reception hall and adjacent administrative rooms were inserted. The wings, together with a 6-7 meter wide corridor, were probably covered in basilica form. Of the patient rooms, there was probably one for each of the sixty-four legion centuries. It measured about 3.6 x 4.6 meters internally and were arranged in sets of three or two, separated by anterooms. The advantage of the latter was to relieve the main corridor in the case of a large number of patients and staff.

The legion headquarter building (principia) consisted of a large paved square surrounded on three sides by porticoes, behind which were arranged various types of offices. On the fourth side of the square was a building in the form of a basilica, behind which was another row of offices and a central chamber intended for the chapel of the legionary banners (aedes). The total width of the principia was about 66 meters, while the length was between 93 and 95 meters, and it could be increased by a projecting annex in the form of a quadrangular passageway. The basilica, 64.4 meters long and 25 meters wide, had a high nave, probably with a clerestory lit by windows, and two side aisles, separated from the main nave by colonnades supported by very solid stereobates, spaced 15.5 meters apart. At both shorter ends of the basilica were deep niches in which the judges’ platforms (tribunalia) were built. In the centre of the colonnades rose massive pillars with arches of brick and limestone tuff, marking a transept 13.5 metres wide, extending from the aedes to the opposite main entrance. The aedes had a stone floor raised slightly above the level of the basilica and benches or platforms on two sides, on which statues were placed. The platforms probably also extended around the rear part of the aedes, where the banners, including the legion’s aquila, were displayed.

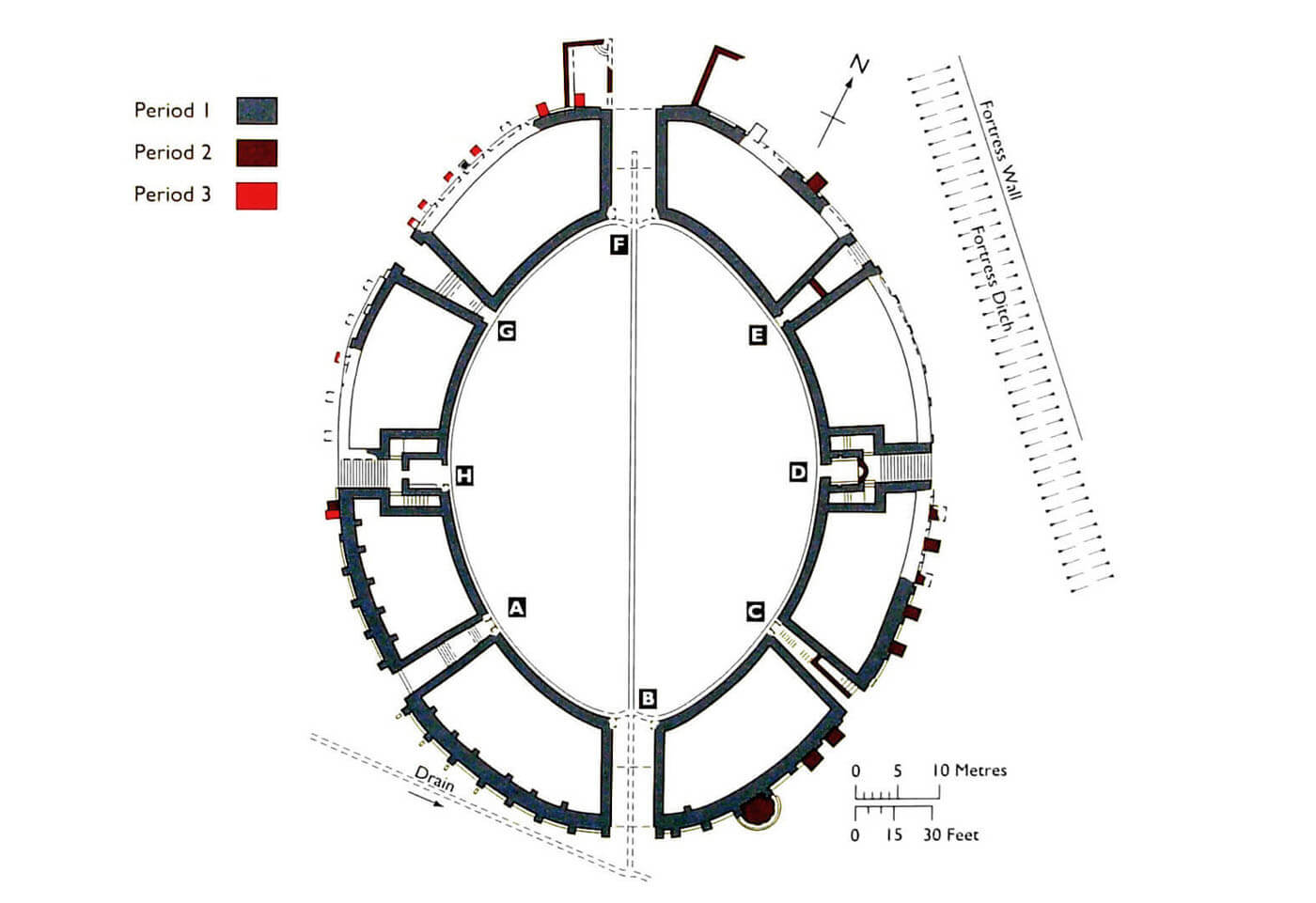

To the south-west of the fort, just outside its fortifications, was an amphitheatre, created on an ellipse plan measuring 41.6 x 56 metres. It was built of earth and walled with a stone wall with external pilasters around the entire perimeter. The higher parts, benches and balustrades, were probably of wooden construction. The gentle slope of the terrain towards the south meant that the northern part of the amphitheatre was cut much deeper into the ground than in the south. There, the stone wall was also noticeably thicker, being 1.8 metres wide compared to 1.4 metres in the north, and the greater height of the above-ground structure meant that it was necessary to additionally support the amphitheatre from the south with external buttresses, spaced approximately every 4 metres. These buttresses were built in place of pilasters, whose structural effect could not be too great. In the following centuries of the arena’s operation, it became necessary to support its wall with massive buttresses on the other sides as well.

The interior of the amphitheatre was accessed through two main entrances (portae pompae) leading directly to the arena, and six smaller ones, regularly spaced, intended for both spectators and artists. The amphitheatre could accommodate up to 6,000 people (i.e. slightly more than a full legion), who could enter it after purchasing a ticket in the form of a lead token. The main entrances in the outer parts received stone barrel vaults, while the parts closer to the arena were not roofed. The entrances were closed with wooden gates, probably double-winged at the main gates. Staircases led from the side entrances to the stands, with the two side entrances on the shorter axis of the amphitheater having two flights of stairs, flanking the rooms where the gladiators stayed before the fight. The eastern stairs were slightly wider and probably led to the main balcony or alcove, where the most important officials sat. A drain ran under the entire length of the arena, effectively getting rid of excess rainwater. Originally, the surface was probably covered with gravel to prevent slipping during gladiator fights or animal shows. The walls around the arena were plastered and covered with red lines imitating stone ashlar.

Current state

Until today, Caerleon has preserved many elements of the ancient Isca fort. The amphitheater survived in the best condition, even now it is use for mass outdoor events, staging and historical reconstructions. Admission to its area, with the exception of special events, is free. To the north-west of it you can see relics of legionary barracks, unveiled during archaeological research. In the town center there is the Museum of Roman Baths with foundations of buildings, mosaics and reconstruction of the pool. The museum is run by Cadw, so the opening times are exactly the same as in the nearby National Museum of the Roman Legion. There is an excellent exposition of artifacts found in the area, as well as reconstruction of the legionaries quarters. Like other national museums and galleries in Wales, access to it is free. In Caerleon, fragments of defensive walls on the south side have also been preserved.

show legionary barracks on map

bibliography:

Boon G., Isca, the Roman legionary fortress at Caerleon, Cardiff 1972.

Knight J., Caerleon Roman Fortress, Cardiff 2003.

Newman J., The buildings of Wales, Gwent/Monmouthshire, London 2000.

Phillips N., Earthwork Castles of Gwent and Ergyng AD 1050 – 1250, Oxford 2006.

Symons S., Roman Wales, Stroud 2015.

Wheeler M., Williams N., Caerleon Roman amphitheatre and barrack buildings, London 1970.