History

Newcastle in Bridgend was built about 1106, according to tradition by William de Londres, one of the semi-legendary Twelve Knights of Glamorgan, as part of the Norman invasion of Wales. William de Londres was a knight loyal to the Norman baron Robert Fitzhamon, and Newcastle was the westernmost part of the area subordinated to Fitzhamon (the only stronghold on the west bank of the Ogmore River). Robert Fitzhamon was probably also the actual founder of the castle in Bridgend. Along with it, the strongholds of Coity and Ogmore were also built.

After the death of Robert Fitzhamon in 1107, Newcastle briefly passed under King Henry II, and from around 1114 to Robert, Earl of Gloucester, son of the monarch who married one of the heiresses of Fitzhamon, founder of Neath and Kenfig castles. Newcastle’s fortifications were strengthened by another owner, William Fitz Robert, the second Earl of Gloucester, shortly before his death in 1183, or by King Henry II, who took over Glamorgan after William’s death. The main reason for this work was the uprising in Glamorgan under the leadership of the Welsh Lord of Afan, Morgan ap Caradog. During its course, the castle was attacked, but the Welshmen did not manage to capture it.

Henryk died in 1189, and the ownership of Newcastle went to prince John, who in the same year handed over the castle, in an extraordinary gesture of conciliation, to Morgan ap Caradog. When Morgan died around 1208, his son Lleison became his successor, who at the beginning of the 13th century commanded 200 Welshmen on the King’s service in Normandy. After Lleison’s death around 1214 the castle was not taken by his brother and heir, Morgan Gam, but Newcastle became the property of Isabel, Countess of Gloucester, King John’s first wife, despite that he was already divorced from her. In 1217, the ownership of the castle changed again. Due to marital affinities it was for a short time in the hands of Anglo-Norman baron Gilbert de Clare, who in the same year handed over the castle to Gilbert de Turberville. The latter, however, preferred to live in Coity Castle. Morgan Gam, disappointed in the expectations of inheriting Newcastle, burned the surrounding villages in 1226, and after the time spent in the Earl’s prison, he allied with the strongest of the Welsh rulers, Llywelyn ap Iorwert. In 1231 and 1232 he made successful raids on Neath and Kenfig, but until his death in 1241, he never managed to capture Newcastle.

In 1360 Newcastle became the property of the Berkerolle family, and in 1411 passed to the Gamages, but no major work was undertaken until the 16th century, when the castle was slightly rebuilt in order to improve the comfort of residents. The castle had no military significance for a long time, especially after the fall of the last Welsh uprising of Owain Glyndŵr at the beginning of the 15th century. Despite the modernization, the building ceased to be a residence at the end of the sixteenth century and gradually began to fall into ruin.

Architecture

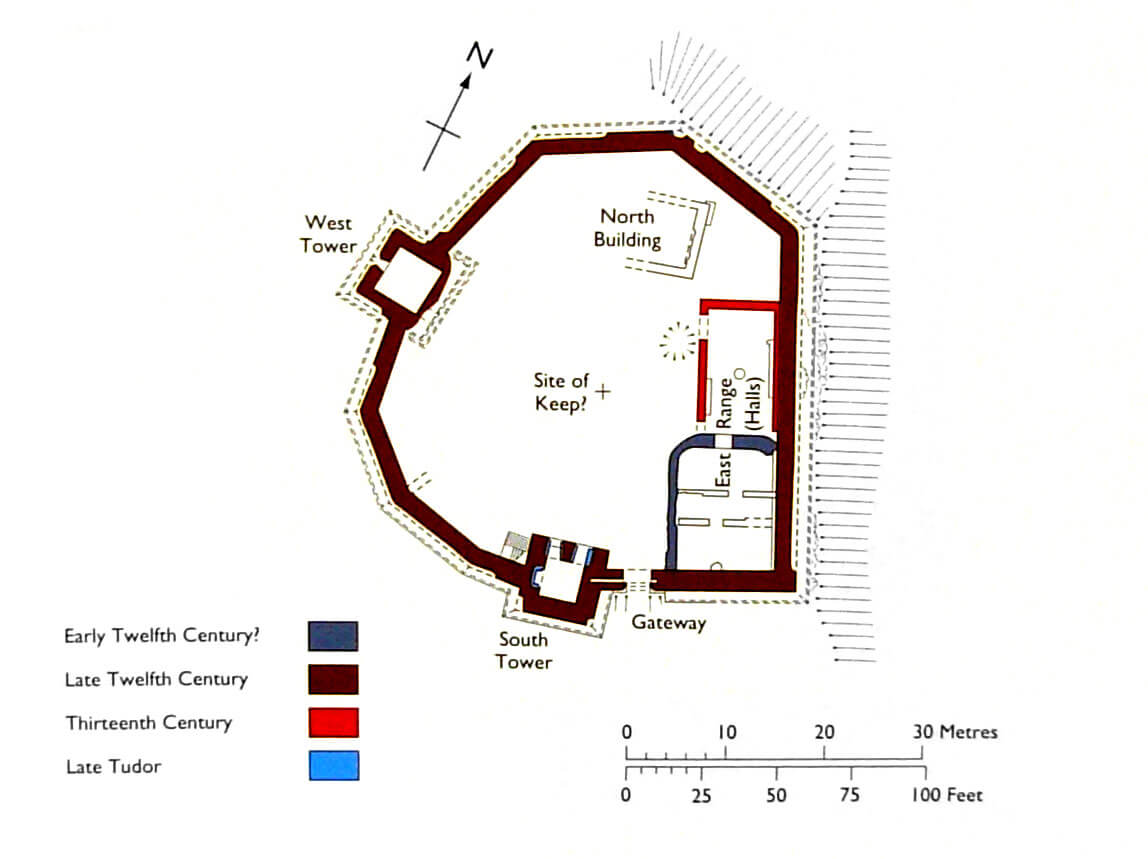

The original defensive site consisted only of a ring of wood and earth fortifications surrounding the courtyard about 40 meters in diameter. Perhaps a keep was built in the middle of them, which relics were supposedly discovered in the 19th century. The whole was protected by a natural slope in the east, descending towards the bend of the Ogmore River (Afon Ogwr), and a ditch from other sides. The castle towered above the floodplain valley and the market settlement of Bridgend on the other side of the river, to which the ford led below. On the west side of the castle the area was flat, but in the north, some protection was provided by a slight re-entrant dingle. From the south, a church was adjacent to the castle, probably located in the outer bailey.

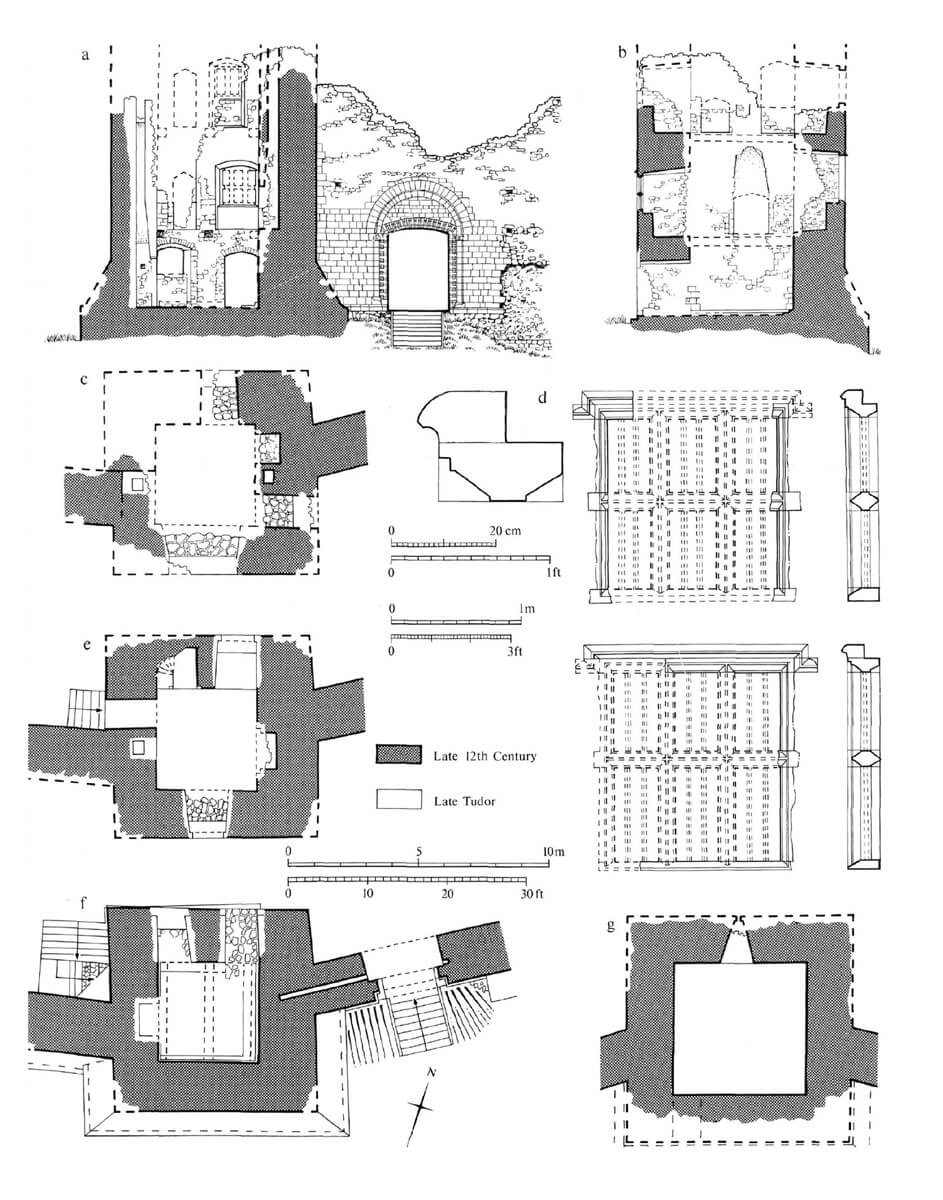

In the second half of the 12th century, a stone perimeter wall was built, and two four-sided towers strengthening it, which were a novelty in the construction of that time in this area (probably they were modeled on the towers of the Earl William’s castle in Sherborne). The wall in the plan had a shape similar to a horseshoe. It was led through a series of short, straight sections, only the eastern riverside curtain was longer. In the thickest places, the wall was about 1.9-2 meters, but it was additionally widened by a meter-wide battered plinth, which was even 1.5 meters wide on the side of the eastern slopes. The height of the wall is unknown, but it had to be more than 6.3 meters (from the courtyard side). It was built of stone, covered on the outside with slightly worked Sutton blocks, as well as ashlar used around architectural details and at the corners.

The southern tower flanked the gate to the castle. The entrance led through a Romanesque portal, distinguished by high-quality stonework, entirely made of ashlar. The passage was closed with a segmental arch embedded in a semicircular recess with a roller in the archivolt falling on the sides on the carved capitals. The portal jambs were decorated with a rare form of four-sided, moulded holes separated by patterns of pellets. The gate was originally closed with a double-leaf door, blocked from the inside with a draw-bar in the openings in the wall.

The southern tower, like the adjacent curtains, had a very wide battered plinth at the base from the foreground side of the castle. The entrance to it led from the courtyard at the ground floor level and from the crown of the perimeter wall to the first floor, through the stairs added to the western wall of the tower. Probably in its lower storey, at least from the end of the Middle Ages, there was a kitchen serving the upper chambers. This storey did not have arrowslits, it was covered with a wooden ceiling. The first floor was rebuilt for residential purposes in the 16th century, when new windows and fireplaces were made in the Tudor style (although at least two fireplaces by the eastern wall were already in use in the Middle Ages). A staircase in the north-west corner led to the second floor.

The west tower was slightly larger, it also protruded to a greater extent in the foreground of the castle in front of the perimeter of the wall. Its base, like the southern tower, was reinforced with a battered plinth, which was also located here from the side of the courtyard. The room in the basement of the tower did not have a fireplace, so it probably had a storage and defense function (a single loop hole). It was accessible through the portal directly from the courtyard.

To the east of the entrance gate, the main residential and economic buildings of the castle were erected, and further to the north an undated building. The oldest structure was the south-eastern building, probably associated with earlier timber and earth fortifications, which is why during the erection of the stone perimeter its southern and eastern walls were removed. Its large width (9.7 meters) indicates that it could be divided by partition walls into smaller rooms. Probably in the 13th century another rectangular building with an entrance from the west was added to it from the north. In its interior, at the eastern wall, there was a stone bench, and in the middle an open hearth, so it probably served as a hall.

Current state

The castle has been preserved in the form of a low ruin, however, most of the monument that has survived to this day comes from the early, Norman period of the castle’s history, probably the best-preserved 12th-century, secular building in Wales. There is a portal of the entrance gate, one of the most beautiful monuments of secular Norman architecture in Wales (the steps leading to it are modern). The south tower has survived to the height of the first floor, although the windows and the fireplace in the ground floor date back to the 16th century, but the first floor has a fireplace from the Middle Ages. The western tower has been preserved only in the part of the ground, while the perimeter walls in the highest places reach 6.3 meters in height. Newcastle is under the care of the Cadw government agency and is open to tourists, free of charge throughout the year.

bibliography:

Kenyon J., The medieval castles of Wales, Cardiff 2010.

Kenyon J., Spurgeon C.J., Coity Castle, Ogmore Castle, Newcastle (Bridgend), Cardiff 2001.

Lindsay E., The castles of Wales, London 1998.

Salter M., The castles of Gwent, Glamorgan & Gower, Malvern 2002.

The Royal Commission on Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales, Glamorgan Early Castles, London 1991.