History

Korlátka Castle was built in the second half of the 13th century, as a guard on the route connecting medieval Bohemia and Hungary, one of several defensive structures protecting the north-western border of the Kingdom of Hungary along the Lesser Carpathians (including Čachtice, Pajštún, Branč). Presumably, the castle was a royal foundation or commissioned by the king. The first but uncertain record of it appeared only in 1289 and connected castle with a certain Ugrin. In 1324, it was recorded under the name Korlathkeu, and in 1398 it was recorded as Korlathku, to later achieve the Hungarian name Korlátkő (derived from the Old Slavic term meaning a fenced stone), and in the 15th century the German Konradstein.

At the beginning of the 14th century, the castle was in the hands of the Austrian knight Ulving from Harcendorf, to whom in 1317 the magnate Máté Csák (Matúš Čák) was to pay in exchange for the stronghold. According to other records, Ulving was supposed to defend the castle on behalf of King Charles Robert against Matúš’s cousin, Štefan Čech. Certainly, after the fall of the Čák family in 1321, Korlátka was a royal property, managed by castellans. In 1394, the castle passed from the hands of King Sigismund of Luxembourg to his closest and most influential advisor, Stibor of Stiboricz. This nobleman of Polish origin came to Hungary in 1362, where he joined the court of Sigismund, from 1378 the king of Hungary, and from 1387 the king of Germany. He distinguished himself in the fights against the Turks, where he supposedly saved the king’s life in the battle of Nicopolis, he also suppressed anti-royal rebellions in Hungary at the beginning of the 15th century. For these merits, he became one of the richest and most influential magnates, owning several dozen castles and several hundred villages.

After the death of Stibor and his son, Korlátka returned to the hands of Sigismund of Luxemburg, who ordered the inclusion of the castle “pro honore” into the property of the Bratislava zupans, so the owner of the castle was to change along with the change in office. However, the zupans did not personally reside in Korlátka, but appointed castle castellans. One of them was Valentín Fekete, recorded in 1438. During the Hussite Wars and the subsequent anarchy after the death of King Albrecht Habsburg, the castle was the seat of knights-robbers and hejtmans with their mercenary troops. In 1440, it was supposed to be the seat of the well-known Hussite Ján Mesenpek of Helfštýn, and in 1444 of the Moravian knight Ján of Moravan called Janda, who used Korlátka to raid the surrounding lands. In the middle of the 15th century, the castle was freed from his hands by the Transylvanian voivode Miklós Ujlaky, who in 1452 gave it to his official, Osvald from Bučany, in gratitude for his loyal service. Osvald’s descendants took over the castle for longer and named themselves Korlátkas. Michal, son of Osvald, lost castle in 1471, when he supported the armed expedition of the Polish prince Casimir, son of Casimir IV Jagiellon, who was pretending to the Hungarian crown. At that time, part of the Polish army was settled in the castle, with the help of which Michal led plundering expeditions. Matthias Corvinus considered it a betrayal and ordered the Bratislava townspeople to lay siege to the castle. After capture, he confiscated Korlátka and gave it to his Silesian supporter, Georg von Stein, which was confirmed in 1481.

At the end of the 15th century, Osvald’s descendants went to court to recapture the castle, then in the hands of the Plankner family. Finally, by the decision of King Vladislaus II of Hungary, they could return to Korlátka in 1494. They also regained their influence and income, because Osvald Korlátka the younger reached the office of the zupan of Komárno and the castellan of the Tata and Komárno castles. The Korlátka family died out with the childless death of Žigmund in the mid-16th century, after which the castle passed to the Nyáry family through family affinities, and in the second half of the 16th century it was divided into four parts between different branches of the family. The division of the estate and the castle continued throughout the 17th century, which gradually led to its neglect with no investment in repairs. In 1704, the castle was occupied by the Kuruc army during the anti-Habsburg uprising. After their departure and the end of the fighting, the castle was completely deserted and fell into ruin in the middle of the 18th century.

Architecture

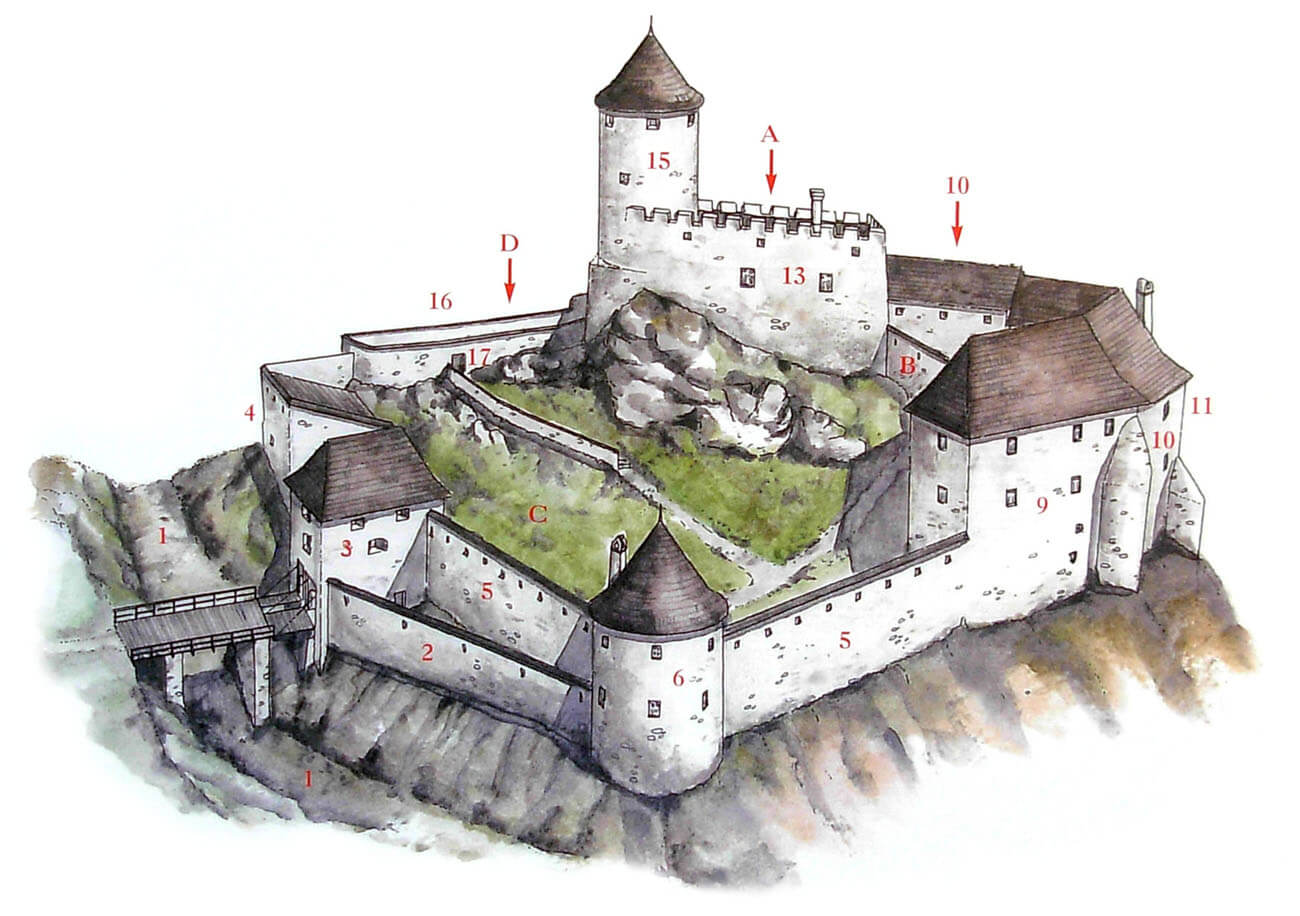

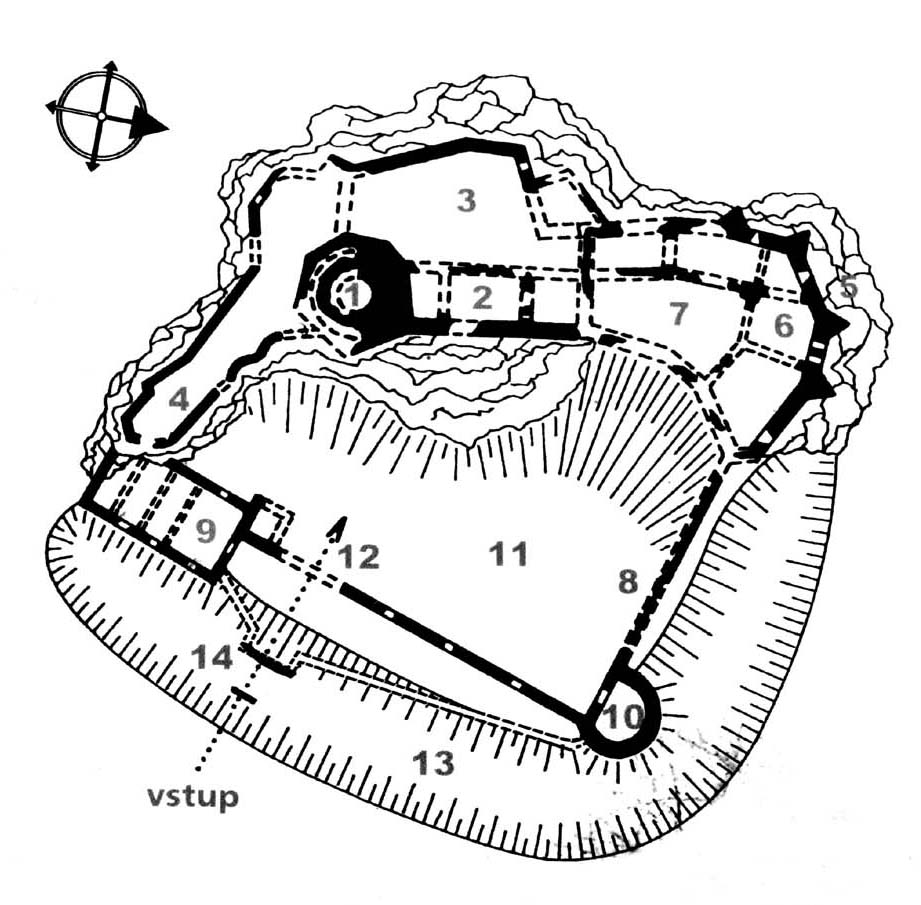

Korlátka at the end of the Middle Ages consisted of the upper ward and as many as three outer baileys. The upper ward, which was the oldest part of the complex, was located the highest on a rocky promontory of the hill, and consisted of a massive main tower and a defensive wall added to it from the north. The tower was a cylindrical structure with an external diameter of about 10.5 meters, with a wall thickness of up to three meters. It probably served as a bergfried, although small windows would suggest that it could also have residential functions. Its interior was divided into at least four floors, separated by wooden ceilings between which people moved using ladders or a narrow staircase in the thickness of the upper parts of the wall. In an unknown period, the lowest storey was supposed to be vaulted. Perhaps after some time there were static problems with the tower, because around the turn of the 14th and 15th centuries it was thickened, giving the ground floor a hexagonal plan.

The defensive wall surrounding a small courtyard on the north and west side of the tower was rebuilt in the first thirty years of the 14th century, using material from the demolished older parts. The new wall was much thicker, it reached a height of about 7 meters and occupied a rectangular area measuring about 20 x 30 meters, i.e. the entire uppermost flattening of the rock promontory. The entrance gate to the upper ward was located on the north side, and in the eastern part there was a residential building by the wall. In the second half of the 15th century, due to the need to raise the standard of living, it was thoroughly rebuilt. Its interiors were heated by stoves and fireplaces, and the lighting from the eastern side was provided by windows with side seats in niches. In addition, in the north-west corner of the courtyard, a kitchen with a hearth and chute was placed, and a water tank nearby, made of carefully prepared ashlar.

To the north and south of the upper ward, there were small outer baileys, which probably developed at the turn of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, although initially without stone buildings. The northern outer bailey, in addition to economic functions, provided additional protection for the access road to the upper ward. A unique feature of its defensive wall were three-sided buttresses placed on the outside, one of which, north-west, turned into a small turret. In the 16th century this buttresses strengthened the older wall from the 15th century, led along the edge of the slopes and topped with a battlement in the crown. The outer bailey gate was located in the north-eastern corner. It is known from records that it was preceded by a drawbridge. During the Middle Ages, economic buildings filled the entire section along the northern and western walls of the bailey, which left only a small courtyard free of buildings.

The southern outer bailey stretched on a rock ridge running out in front of the upper ward, where it additionally secured the main tower. Unlike the economic and defensive northern bailey, the southern one probably had only military functions. On the south side, it turned into a small hill protruding several dozen meters into the foreground of the castle, located in front of the ditch of the outer bailey, which was probably secured with wooden and earth fortifications measuring about 50 x 55 meters. In the first half of the 16th century, on the site of the original fortifications of the southern bailey, a stone wall was erected with arrowslits for small arms and a postern leading to the eastern bailey.

The most extensive outer bailey stretched on the eastern side of the upper ward. It was formed in the first half of the 16th century due to the need to gain more space. It was protected by a defensive wall with a wooden porch and loop holes for handguns, a corner, cylindrical tower, extending entirely in front of the perimeter towards the ditch, as well as an additional, lower defensive wall with a four-sided gatehouse located on the front (eastern) side. The outer defense zone was a ditch in the north and east with a drawbridge over it. It was probably the oldest part of the eastern outer bailey, dug up in the 15th century, when the outer bailey was of wooden and clay construction.

The main stone building of the eastern bailey was located on the southern side, at the base of a rock. It had the shape of a rectangle with three main floors. The ground floor with loop holes had defensive functions. The second floor was probably intended for economic purposes, as was the third floor illuminated with small windows. In the attic there were more slit loop holes. At the end of the 16th century, the ground floor of the building was vaulted, and the floors were adapted for residential purposes.

Current state

Small fragments of the perimeter walls and a slender fragment of the main tower, reaching about 10 meters in height, have survived at the upper ward. On the highest preserved section of the defensive wall, relics of crenellation and a Renaissance attic placed above it, resembling battlement, are still visible. In the corner you can see the relics of a brick kitchen stove and a chute hole. The fortifications of the outer bailey, headed by the eastern curtain and the north-west corner with triangular buttresses, have survived in a slightly better condition. In the eastern outer bailey an economic building in the southern corner stands out. It has preserved the perimeter walls, but its lowest, vaulted storey is now covered with rubble from the collapsed parts. Recently, restoration works have been carried out at the castle, and the vegetation overgrowing the stronghold has been cut down. Admission to the ruins is free.

bibliography:

Bóna M., Plaček M., Encyklopedie slovenských hradů, Praha 2007.

Janura T., Matejka M., Šimkovic M., Hrad Korlátka, Bratislava 2013.

Wasielewski A., Zamki i zamczyska Słowacji, Białystok 2008.