History

The Gothic church of St. Martin began to be built at the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries, on the site of an earlier, Romanesque building from the 11th or 12th centuries, after Pope Innocent III allowed the chapter to be moved from the castle to the city (permission was issued in 1204, but the actual transfer took place much later). The construction of the Gothic church could also be related to the damages caused in 1271 by the Czech army of Ottokar II. Probably during this period the church of St. Martin began to perform parish functions, thanks to the prestige of the chapter as the highest Church institution in the city. The function of the Bratislava parish priest was first recorded in 1304, when an agreement was concluded between the mayor Hertlin, the city representatives, provost Serafin and the members of the chapter, establishing the conditions for his election. According to the agreement, the parish priest was to support a vicar and a chapter teacher, who at the same time performed the role of a chorister in the church along with the students.

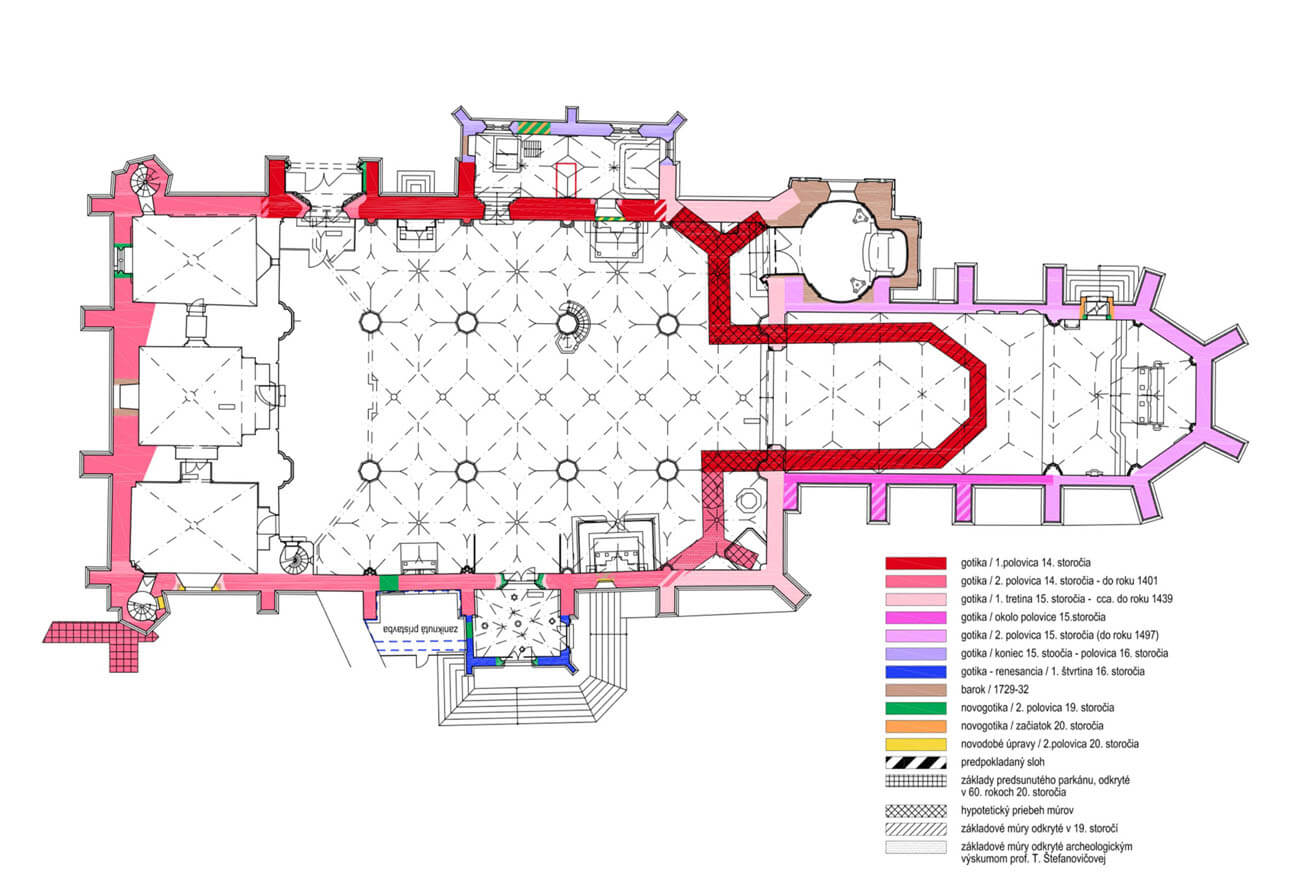

The construction of the Gothic church probably began to be carried out more intensively around the second decade of the 14th century, after the political and economic situation had stabilized due to the end of the ruling Árpád dynasty and the struggles for the Hungarian throne. In 1318, the Archbishop of Esztergom issued an indulgence for all who would visit the church (“qui ecclesiam Sancti Martini adjuverint”), which was usually associated with raising funds for construction works. Further indulgences were granted in 1339. However, the construction of the church progressed with certain problems, marked by a dispute between the chapter and the city, which did not want to finance the construction works. In addition, the method of appointing the parish priest had to be established, from the beginning of the 14th century elected by the city council from among the canons, with the consent of the provost and chapter. This method was changed in 1348, when the rights of the burghers with the privilege of patronage were increased. After the chancel was built in the 1320s, the church was enlarged with a nave until the end of that century, when it was integrated with the second line of the city defensive wall.

At the beginning of the 15th century, construction work on the church intensified again, with an attempt to restore strong royal power by Sigismund of Luxembourg in alliance with the large cities of the kingdom. Bratislava then became the ruler’s temporary residence, where he stayed during his numerous journeys to Austria, Germany and Bohemia, and which he endowed with numerous political and economic privileges. Luxembourg also supported the construction of St. Martin’s Church, specifically its two western chapels at the tower, created on the model of the Vienna Cathedral. Their construction was supposed to be connected with the modification of the course of the city defensive walls, although this intention was never fully realized, even after Queen Sophie, the wife of Wenceslas IV, who found refuge in Bratislava after fleeing Bohemia, took over the construction patronage over the western part of the church. However, in the early 15th century, the closures of the aisles were rebuilt, finally forming the shape of the nave.

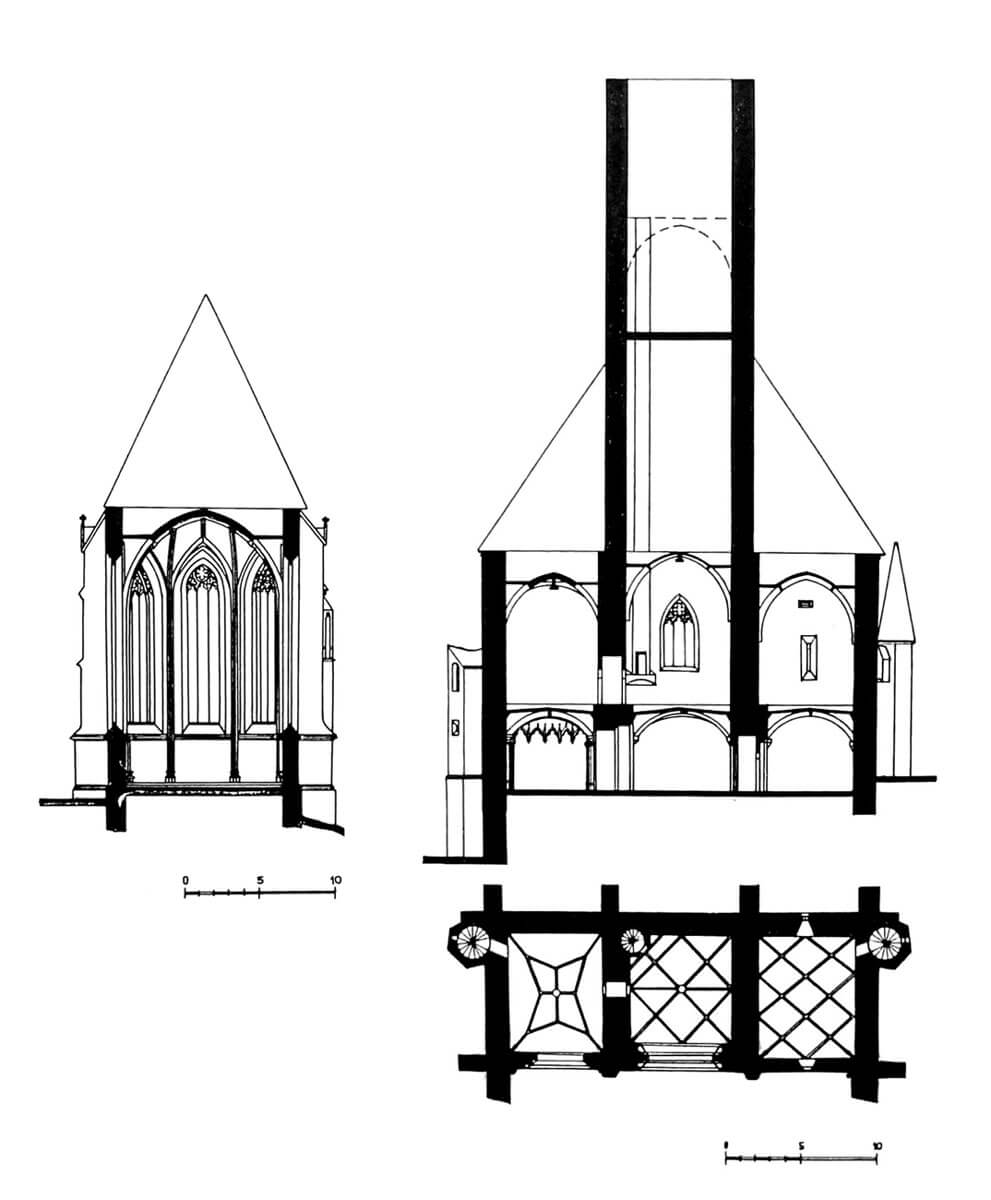

More serious construction works on St. Martin’s church were suspended in the years 1427-1435 due to the Hussite threat. It was not until the end of the first half of the 15th century, under the supervision of the Viennese master Hans Puchsbaum, that the vaults of the nave were installed, thanks to which the ceremonial consecration of the church could take place in 1452. However, the dimensions of the nave after completion turned out to be completely incompatible with the small chancel built 150 years earlier, so in the second half of the 15th century, on the initiative of provost Georg Schomberg and with the support of King Matthias Corvinus, construction of a larger, late Gothic eastern part of the church was undertaken, completed around 1487. The chancel was designed by the Viennese master Laurenz Spenning, although its size and representativeness concealed the ambitions of the city’s patricians. The last major late Gothic construction works were carried out not only in the times of Matthias Corvinus, but also at the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries, when the chapel of St. Anne was added to the north, and also in the first quarter of the 16th century, when the southern porch was built.

In 1541 Buda was occupied by the Turks, thanks to which Bratislava took over the role of the most important city of the Christian part of the Kingdom of Hungary. Its parish church began to serve as the coronation temple of Hungarian kings (the third one after the fall of Esztergom and Székesfehérvár), and soon after became one of the most important burial places of the Hungarian political elite. In 1563 in the church of St. Martin, Ferdinand I Habsburg organized the coronation of his son Maximilian and his wife Maria. Then, in 1572, Rudolf II Habsburg was crowned as the ruler of Hungary. Subsequent enthronements took place in Bratislava in the 17th century, with the exception of three carried in Sopron.

In the years 1729 – 1732 a Baroque chapel was added to the church, in 1764 – 1765 the church tower was raised by one storey and the western façade and the facade of the tower were radically modified in the Baroque style. Attempts were made to remove these changes in the period 1835 – 1846, when the tower and the entire façade of the church underwent neo-gothic reconstruction. This renovation was provoked by a fire from 1833, caused by a lightning strike that destroyed the Baroque helmet. The neo-Gothic reconstruction of the tower was the prelude to further works, in 1854 connected with the renovation of the northern chapel. The repairs of the church took place in the years 1863-1878, carried out thanks to the establishment of the church renovation group. Minor structural modifications were also introduced in 1905, however, it did not significantly affected the form of the church. Major repairs were financed only in the years 1968-1970, when the last Baroque accretions of the façade and some of the neo-Gothic elements were removed.

Architecture

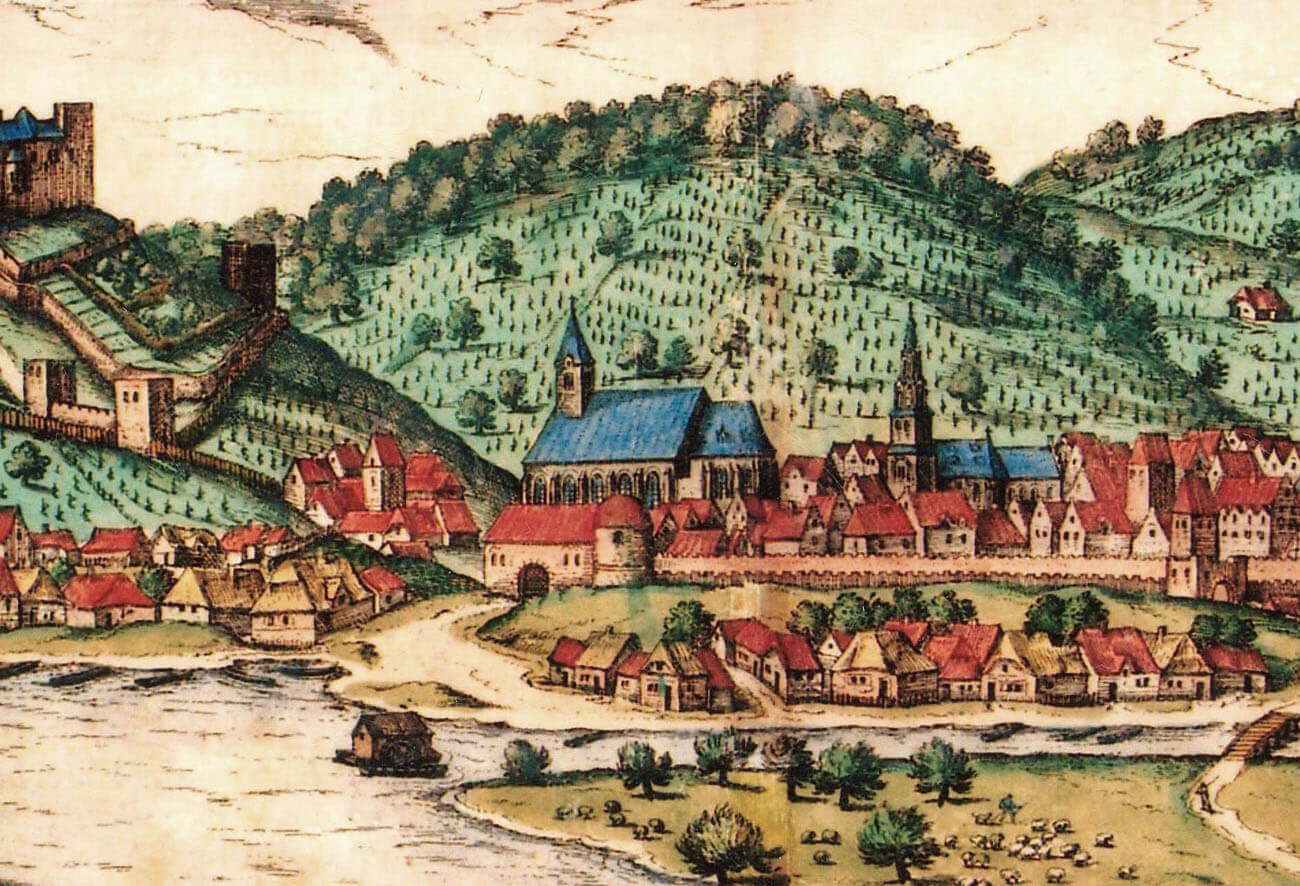

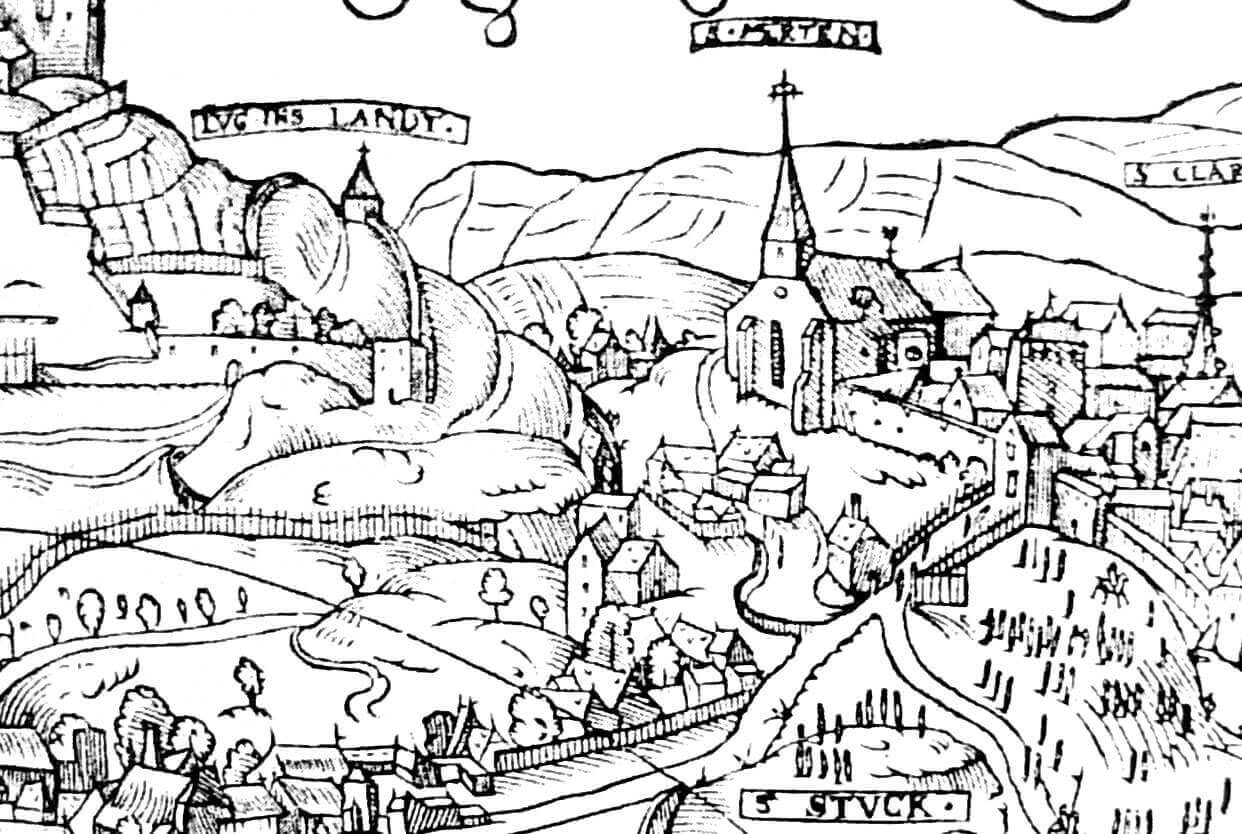

The church of St. Martin was built in the southwestern part of the medieval city, with its façade placed on the line of the city defensive walls. It was an unusual location, very far from the city market square, resulting from the location of the older, Romanesque chapter church, which was originally built on the grounds of the castle outer bailey, later absorbed into the expanding city. At the time of the construction of the Gothic church, there were no more free plots in the central part of the city, and on the other hand, the church could have been used to strengthen a section of the city fortifications. On its southern side, the gate was located a short distance away, while to the north, a road ran from the church square towards the Poor Clares nunnery. From the east, the church was probably limited by dense residential development.

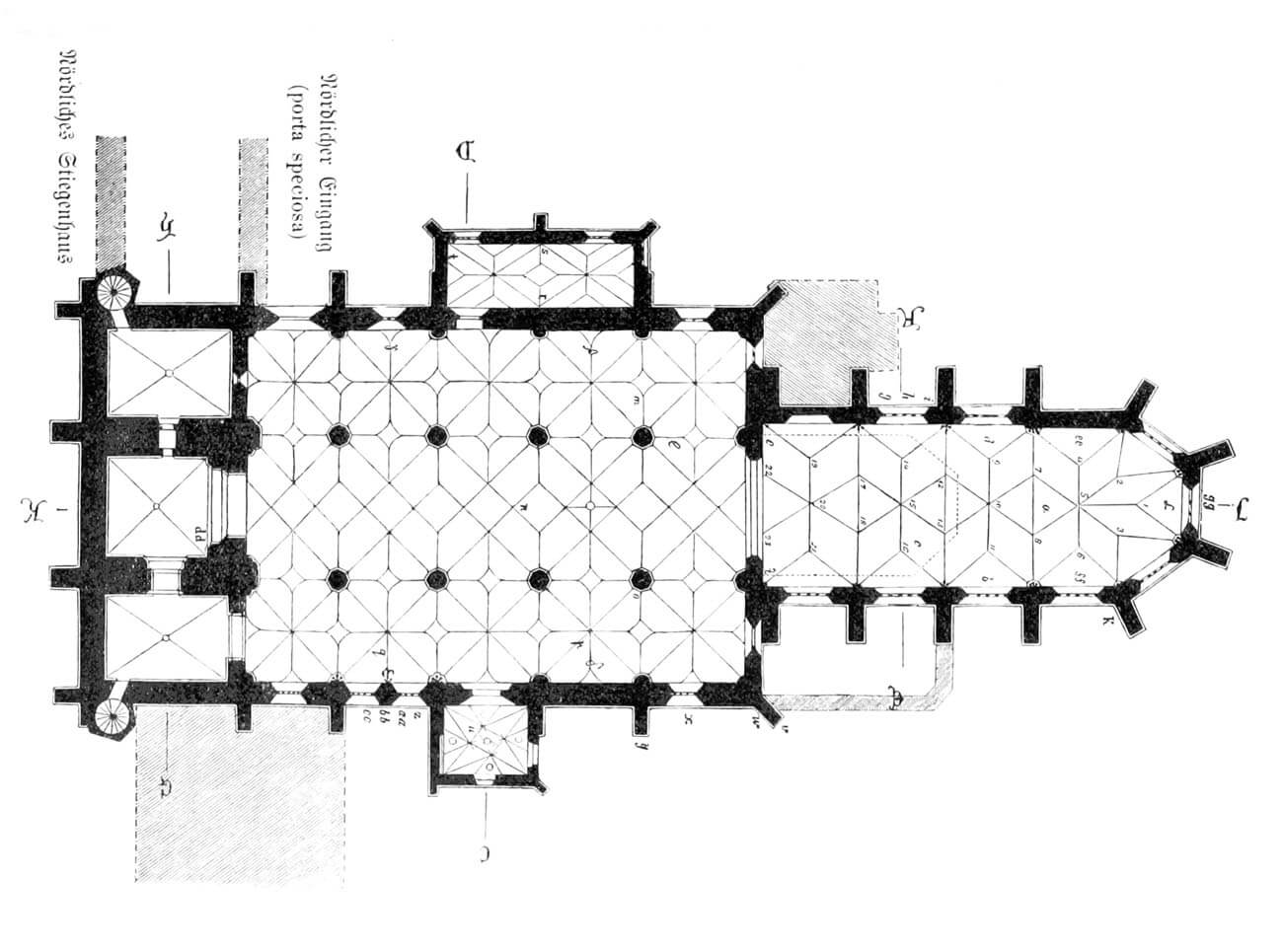

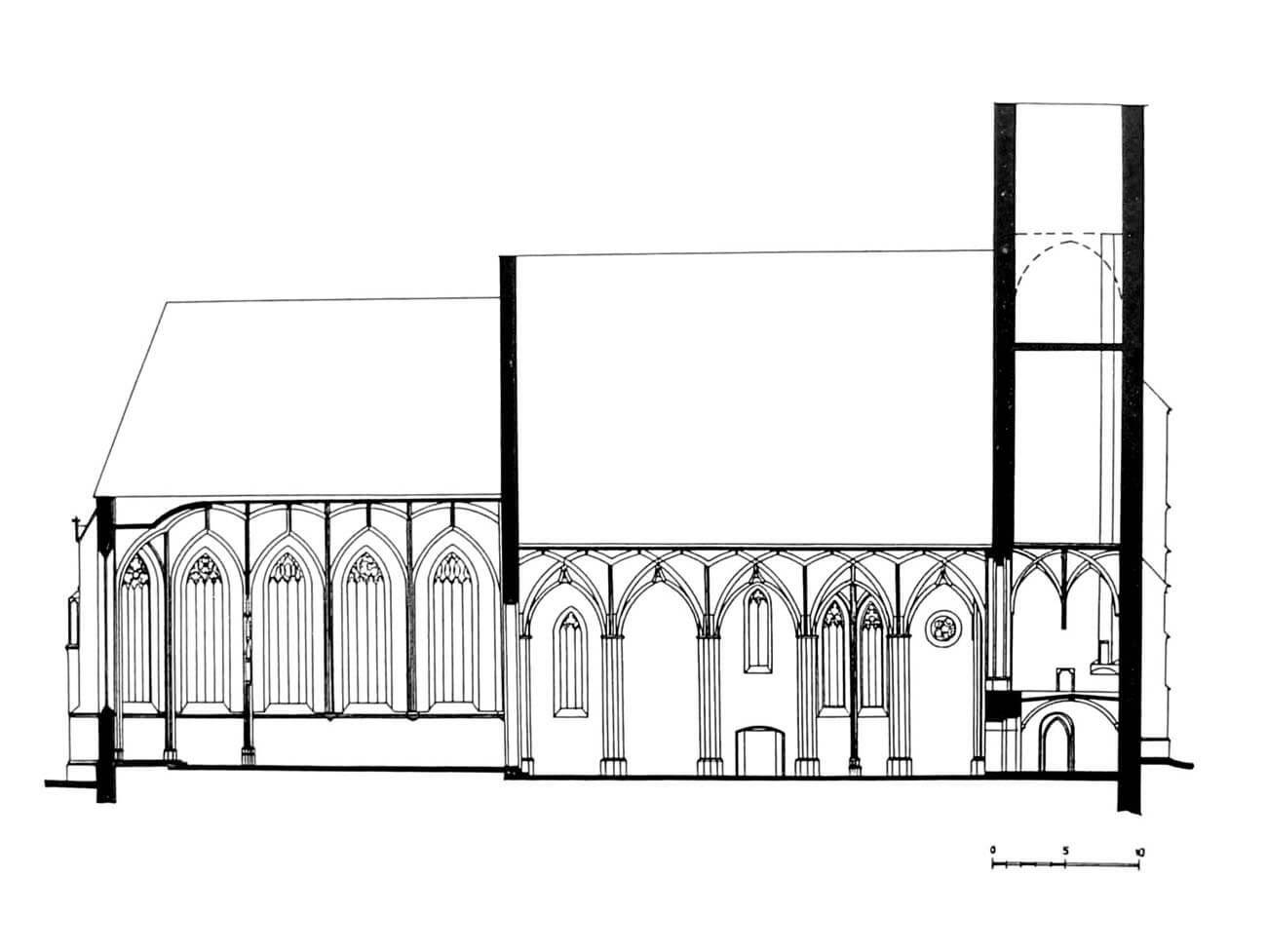

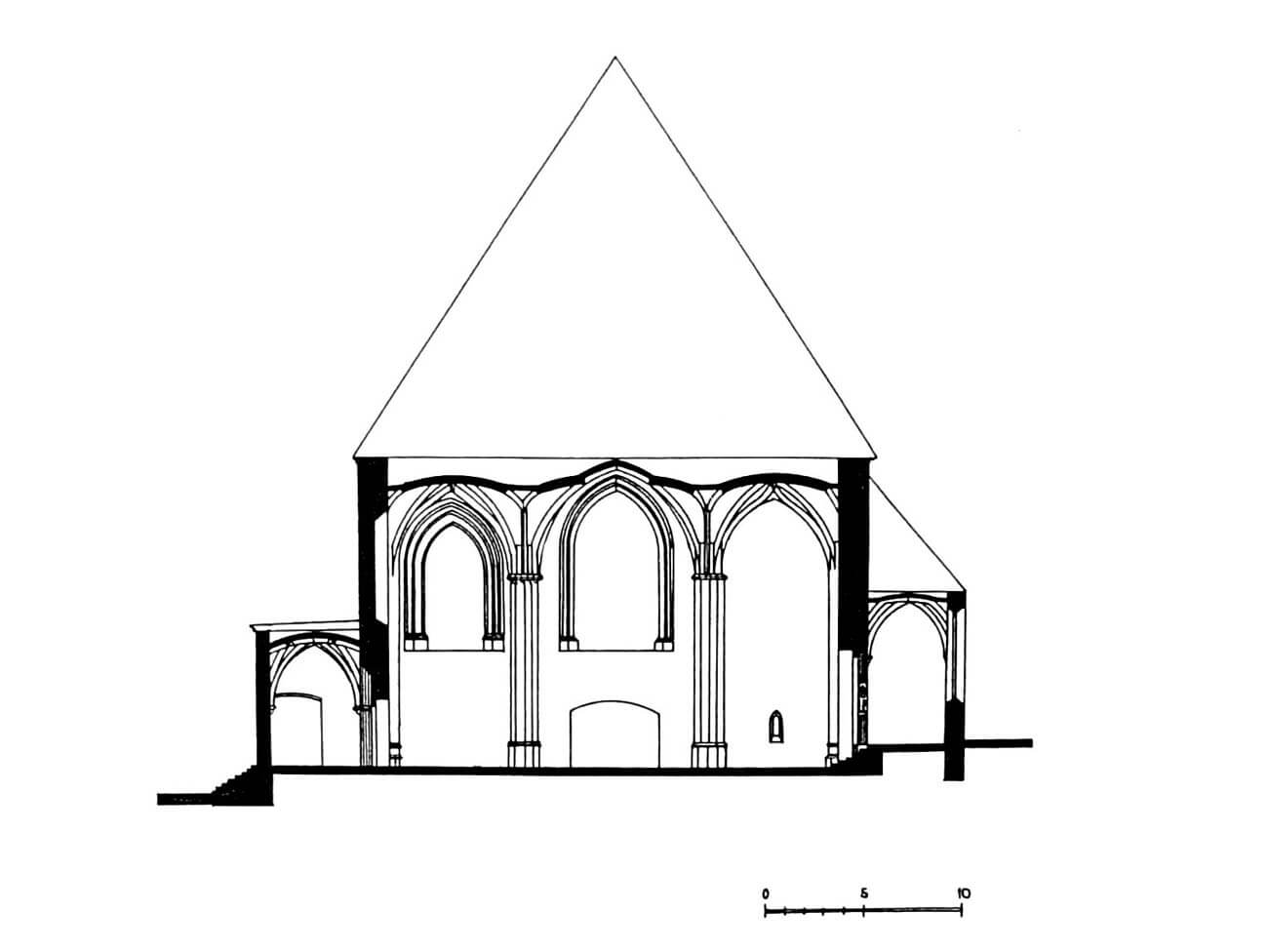

In the Gothic period, the church was an aisled building with a nave initially four bays long, on the eastern side of which there was a narrow chancel with a three-sided closure, characterized by a slight deviation to the north. The nave was perhaps originally planned as a basilica, but ultimately it was decided to go with an innovative hall structure, modelled on churches in Swabia, with the parish church in Schwäbisch Gmünd at the forefront. The central axis of the façade, built at the beginning of the 15th century, was originally a low and squat quadrangular tower, flanked from the north and south by chapels extending the aisles. From the east, the aisles were initially ended with diagonally arranged walls, as they were still connected to the old, small chancel from the beginning of the 14th century. When the construction of a much larger late Gothic chancel was undertaken in the second half of the 15th century, the eastern endings of the aisles were transformed into straight ones, at the same time extending the aisles by an additional bay. The late Gothic chancel was ended in a similar way to the older one, with five sides of an octagon. Then, at the end of the 15th century, a two-bay chapel of St. Anna was built from the north, and at the beginning of the 16th century a late Gothic porch to the southern aisle.

On the outside, the nave of the church was reinforced with stepped buttresses, between which moulded, tracery-decorated windows with pointed heads were placed. Only the small 14th-century chancel was not clasped with buttresses, but the more impressive, vaulted 15th-century chancel required reinforcement with buttresses, which, unlike the older ones, were decorated with blind traceries. Among the windows, a large oculus with tracery in the southern wall of the aisle stood out, created high because of the defensive wall connected to the church below. The horizontal divisions of the church elevation were introduced by a moulded plinth cornice, a crowning cornice and drip cornices in the chancel and northern chapel, with the drip cornice in the latter being bent to enclose the windows. The tower on the highest floor was pierced with large pointed tracery windows with wide grooved frames. On their sides there were originally consoles and canopies for carved figures, which together with the frieze under the crowning cornice gave the tower a picturesque appearance. The decoration was complemented by draining water gargoyles, including one in the form of a dog monster with a long neck, pointed ears and a snarling muzzle. All the aisles and central nave were covered by a single gable roof, topped on the east by a triangular gable dominating the lower roof of the chancel.

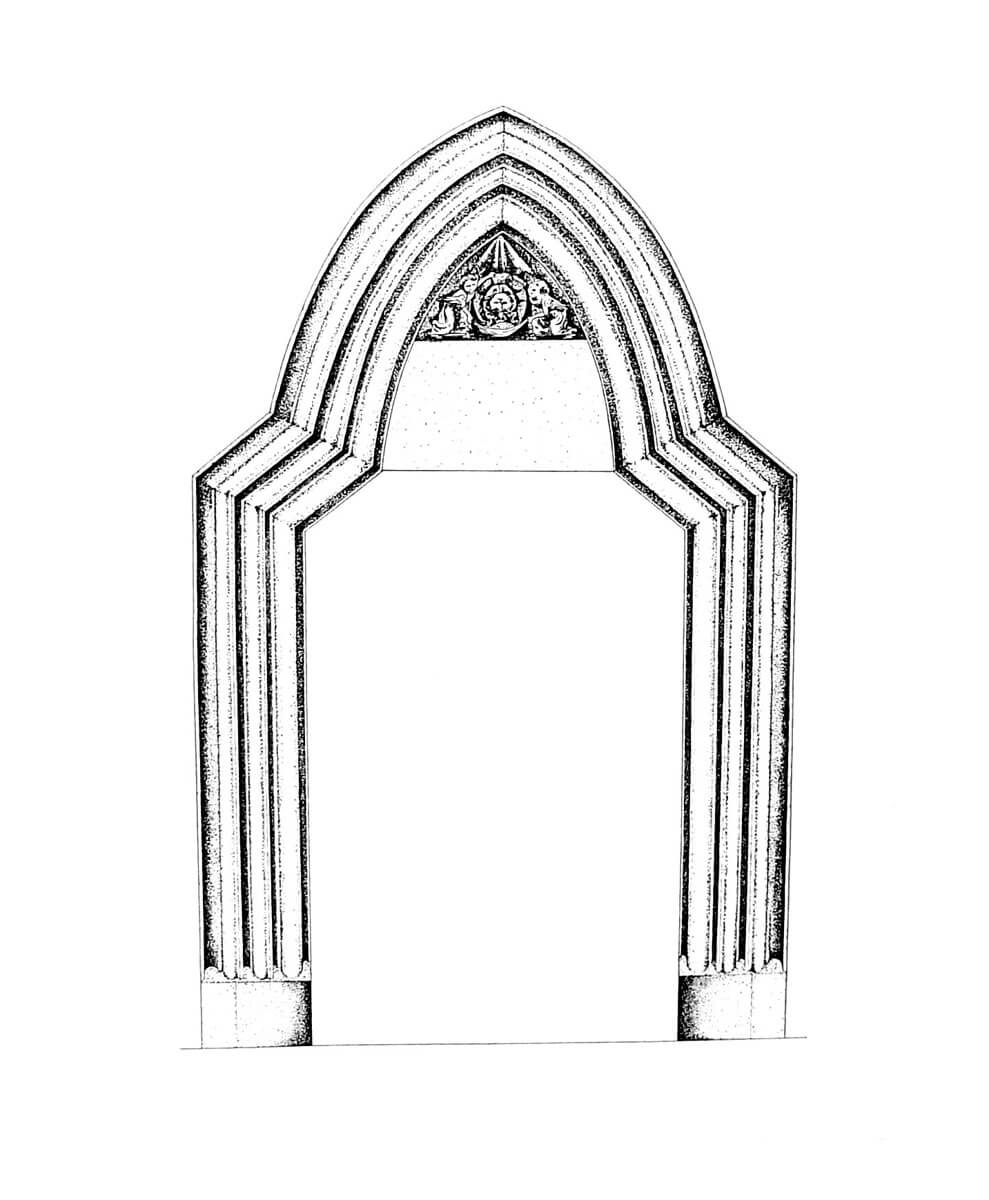

The entrance to the church led through the aisles from the north and south. The main one was originally the northern entrance in the second bay from the east, where an impressive portal was placed. Its composition was made of pear-shaped rollers of moulding, led from a low plinth to a pointed archivolt. The moulding was interrupted on both sides by a console and a canopy, intended for figures of saints. In the tympanum, on the other hand, a bas-relief personification of the Holy Trinity was shown in a frontal view, surrounded by plant and animal motifs – a pelican and a lioness feeding their young. At the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries, the portal became an internal passage to the chapel of St. Anne, but on its western side there was still a northern portal from the beginning of the 15th century, with rich moulding connecting the plinth with a semicircular archivolt and with a zone of capitals decorated with bas-relief plant motifs. The tympanum of the portal was decorated with a kind of blind tracery, two arches inspired by Viennese art, combined with the moulding of the archivolt. There may have originally been a painting between the arches.

The seemingly more modest original southern portal had a pointed and narrow archivolt, set on two oblique arms. The whole was moulded without division from the plinth to the archivolt and supplemented by a bas-relief tympanum with a motif of Veraicon carried by two angels. The originality of the portal was manifested in the unconventional combination of three different geometric shapes: a rectangle, a triangle and a pointed arch, which in effect created a rather complicated composition, atypical of the basic assumptions of the Gothic style. At the beginning of the 15th century, there were also plans to create a portal in the southern chapel by the tower. It was to be pierced high, because a ramp from the castle side, placed over two lines of defensive walls, was to lead to it, but ultimately this undertaking was never completed. The portal was to have a profile very similar to the northern portal from the 15th century.

The interior of the nave was covered with net and cross vaults, divided into rectangular bays in the central nave, and into square ones in the aisles. The church was divided into aisles by four pairs of octagonal pillars with high plinths. In their high capital zone, consoles supporting the ribs were suspended on the cornice. At the longitudinal walls, the ribs were springing from rounded shafts. A characteristic feature of the vault were bent ribs and free bifurcated ribs, embedded in the middle of the bays directly into the walls, without the intermediary of consoles. It partially eliminated the division into aisles and bays, unifying the interior space. The chancel was fitted with a stellar-net vault, modelled on the Milevsko version of the Peter Parler vault, consisting of alternating six-pointed stars. The chancel ribs were fastened with twenty-three bosses in the shape of the coats of arms of cities, families and regions that supported the construction of the eastern part of the church or were associated with the main sponsor – King Matthias Corvinus. On the walls, the ribs were onto slender shafts, between the third and fourth bays covering the more massive wall pillars. The shafts intersected or were set on the cornice, introducing a horizontal accent into the chancel interior. In the presbytery closure, Laurenz Spenning used progressive two-stage plinths of the shafts, moulded with vertical and screw-twisted grooves. He enriched the shaft bundles in front of the eastern closure with slender canopies, under which figures were to be placed on the consoles. From these, he created the southern canopy using his favourite motif of interpenetrating ogee arches.

The interior of the northern chapel was covered with a vault similar to the ones used in the aisles, but without the bent ribs. In the southern porch, on the other hand, a network of parallel ribs was used, running in pairs, bypassing the central point and the corners. This motif came from the Anton Pilgram, the last of the great masters working on the Vienna Cathedral. Although the ribs in the porch were not springing directly from the corners, a short, cylindrical, corbel-ended shaft was inserted between each pair of ribs flanking the corner, somewhat negating their functional justification. The porch was the culmination of an individual, improvisational approach to the system of supporting the vault. The corbels were made of plastically shaped stars, polygons and other prismatic figures, resembling polished gems. In addition, the central boss was suspended freely, without contact with the ribs, like a flower growing from gnarled branches.

The tower, together with the western facade of the church, was originally located behind the line of the main city wall, in the area of the zwinger. It was part of the city’s fortifications and therefore had no entrance portal from the west that potential attackers could use, or even windows (only small slit openings). In order to improve communication, a pair of small side turrets with staircases were placed at the western elevation. Inside, the part under the tower of the church was divided into three rooms by internal walls: in the south there was the chapel of Queen Sophia, in the middle the sacristy and in the north the chapel of the canons. The first floor originally housed the oldest library in the city, the chapter archive and the imperial chapel of Sigismund of Luxembourg. The middle part of the first floor opened into the nave with a gallery.

The interiors of the chapels by the tower were to be characterized by architectural complexity inspired by Viennese art. The motif taken from the elevations of the cathedral was to be blind arcades, consisting of a series of finely moulded pointed arches, created with a barely noticeable accent of a ogee arches, from which bas-relief fleurons derived. A trefoil blind tracery was inscribed in each pointed arch, and a bas-relief pinnacle was derived from between each arcade. In addition, small flowers with stems placed on archivolts were arranged along the edges of the pointed arches. The arcades were set on moulded cup-shaped consoles, among which one took the shape of the so-called wild man, as the only one signed with a stonemason’s mark (a face with a crooked smile, large ears, bulging eyes and hair somehow attached to the architectural element). All three rooms on the ground floor of the western part of the nave were covered with low, segmentally flattened cross-rib vaults. The wedge-shaped ribs were springing from the corners from strongly elongated pyramidal corbels, unusually divided into three parts according to the rib springings and at the same time connected by cornices.

The rooms on the first floor were created much higher, covered with more complicated and creative vaults, based on the Bavarian achievements of Hans von Burghausen, who revised the 14th-century legacy of master Petr Parler, the famous builder of the Prague Cathedral. Each of the rooms was covered with a different vault, although all of them were connected by the pear-shaped profile of the ribs and the way they were springing from the corners without the consoles. In the southern room, the ribs created a motif of a figure that was a compromise between a cross vault and a stellar vault (a star without diagonal ribs in the axes of the arms), in which the arms did not reach the edges of the room, but were created by branching diagonal ribs. The central vault divided the room by a transverse rib into two equal parts, each of which was filled with pairs of crosses, effectively combining into a large cross vault that would have disappeared into the typical late Gothic network of ribs if not for the boss at the central intersection. In the northern room, the master builder used a dense network of parallel diagonal ribs throughout the space.

Current state

The church has the spatial arrangement obtained in the Middle Ages and mostly the body of the nave, chancel, tower and annexes. Once having defensive functions in connection with the neighboring city wall, the western façade has been transformed. Its current form with a large neo-Gothic windows on the first and second floors is the result of renovations in the 1970s. The spire of the tower has an early modern form, moreover, its entire top floor comes from the 18th century, currently pierced with neo-gothic windows. Another, entirely early modern element of the church is the chapel on the north side of the chancel. Some of the architectural details were replaced, transformed or renewed, such as the southern portal of the porch and portal inside the porch, or the northern portal of the chancel. Among the original architectural details, it is worth mentioning the north portal from around 1340, currently located in the late-Gothic chapel of St. Anny, a machicolation box at the north-west corner, originally connected with the city defensive walls, numerous tracery windows. Inside, noteworthy are the 15th-century vaults of the nave, chancel and chapels, along with their entire support system and decorations.

bibliography:

Bagin A., Rusina I., Toranová E., Žáry J., Dóm sv. Martina v Bratislave, Bratislava 1990.

Gojdič I., Tihányi J., Bratislava. Kostol sv. Martina. Architektonicko-historický výskum fasády veže a západnej fasády [w:] Ročenka pamiatkových výskumov 2010, red. M.Orosová, Bratislava 2012.

Lexikon stredovekých miest na Slovensku, red. Štefánik M., Lukačka J., Bratislava 2010.

Ortvay T., Geschichte der stadt Pressburg, Pressburg 1892.

Slovensko. Ilustrovaná encyklopédia pamiatok, red. P.Kresánek, Bratislava 2020.

Šedivý J., Az egyház a középkori Pozsonyban. Régi választások és új kérdések [w:] Fejezetek Pozsony történetéből magyar és szlovák szemmel, Bratislava 2005.