History

The church and the friary were founded in the 1230s by Henry the Pious for the Franciscans brought from Prague. It was probably built on the site of an older building dating back to the 12th century. The first source reference to the appearance of the Franciscans in Wrocław comes from 1234, and subsequent records about the church of St. James are associated with the creation of the Czech-Polish province at the provincial chapter in Prague in 1238. A year later, a chapter was held in Wrocław under the leadership of the Czech-Polish provincial Tworzymir.

Still in the process of building, crypt of the church became the burial site of the founder, who in 1241 died in the battle with the Mongols at Legnica. In this church, mentioned in 1254 as completed, in 1261 the foundation privilege of the New Town was announced, enabling further development of Wrocław. This act was issued by the sons of Henry the Pious, Henry III and Władysław in the presence of Princess Anna and Bishop Thomas I, so the ceremony at that time had to be magnificent. Another personage buried in the friary church was the Wrocław patrician Tylo and his wife Margaret, who made significant donations for the reconstruction started in the first half of the fourteenth century. They were buried in 1361 in the chancel of the church, which must have been completed or close to completion then.

Due to lack of funds, the reconstruction of the nave took a long time and had breaks. Foundations for it were recorded in 1368, 1422 and 1433, but also in 1513 the sources noted a significant donation for the construction of a church and friary, and in 1514 for the construction of St. James. The church tower had to be ready by 1441, when a lightning strike burned the wooden structure of its helmet. The friary probably experienced the peak of its successful development at the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries. In 1512, the friary church was to have as many as 20 altars, and in the cloisters there was a guardian with 30 brothers.

At the beginning of the sixteenth century, the Franciscans were either largely Protestant or left Wrocław. The friary was abandoned by the Franciscans and was taken over by the Premonstratensians monks from Ołbin. They dedicated it to their patron, Saint Vincent. In the following years, the Premonstratensians became impoverished, so no renovation works were carried out on the friary and church. The situation improved only at the beginning of the 17th century, thanks to which the first major renovation was carried out in 1620, in the years 1662-1674 the church received rich Baroque furnishings, and in 1682-1695 the friary was rebuilt in the Baroque style. After the secularization of the order in 1810, the church was converted into a parish, and the monastery buildings were designated for the seat of the court. In the last days of World War II, the church suffered heavy damage. The tower collapsed, and with it a part of the side wall and vaults. Preserved in good condition the stalls were transferred to the choir of the cathedral. The restored church was handed over in 1997 to the Eastern Orthodox Church.

Architecture

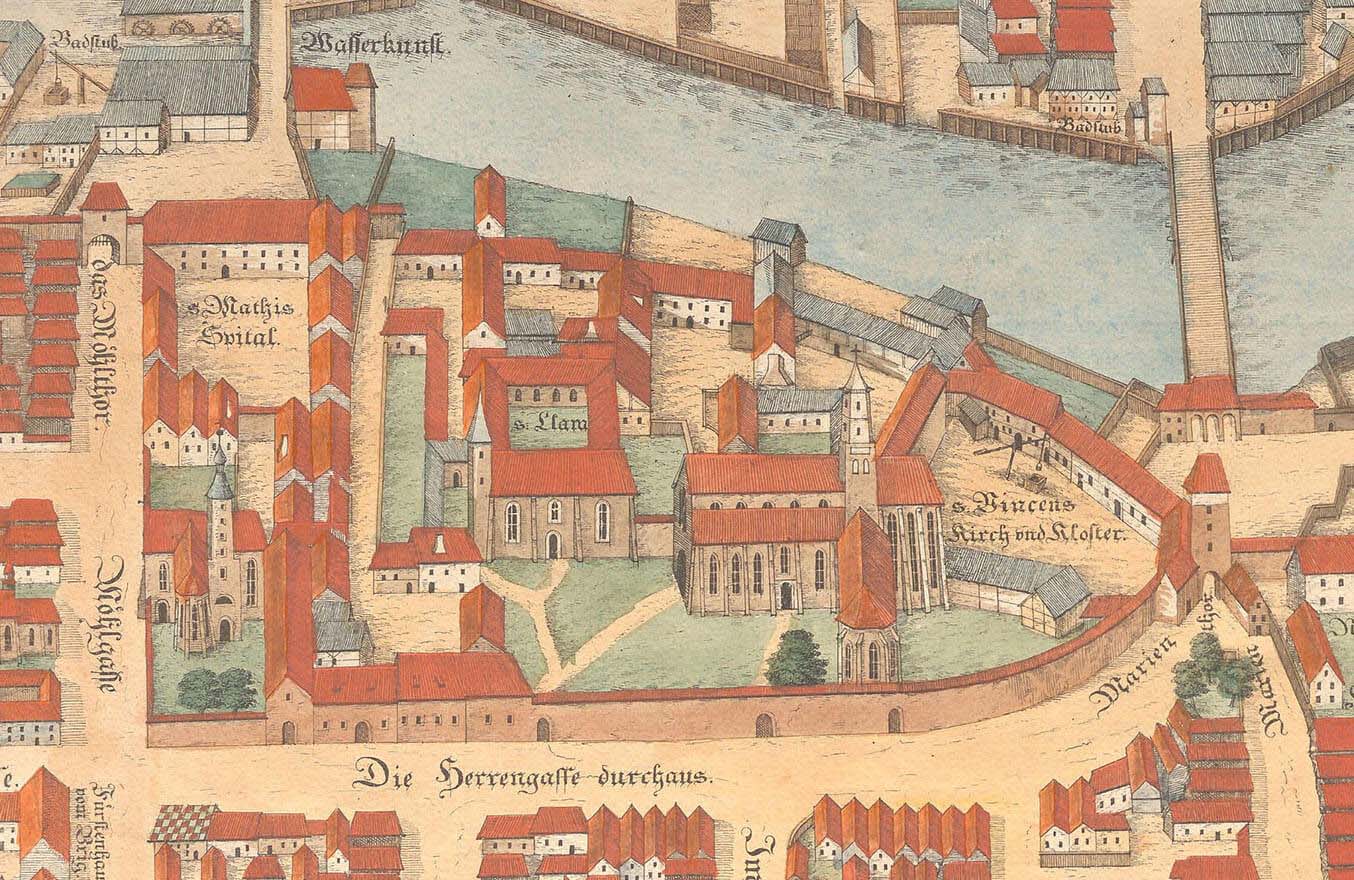

The church of St. James was built on the left bank of the Oder, in the northern part of the Old Town, on a fragment of the ducal area located near the ferry to Sand Island. Originally, in this area there was the ducal residence and associated with it settlement, organized by prince Henry the Bearded.

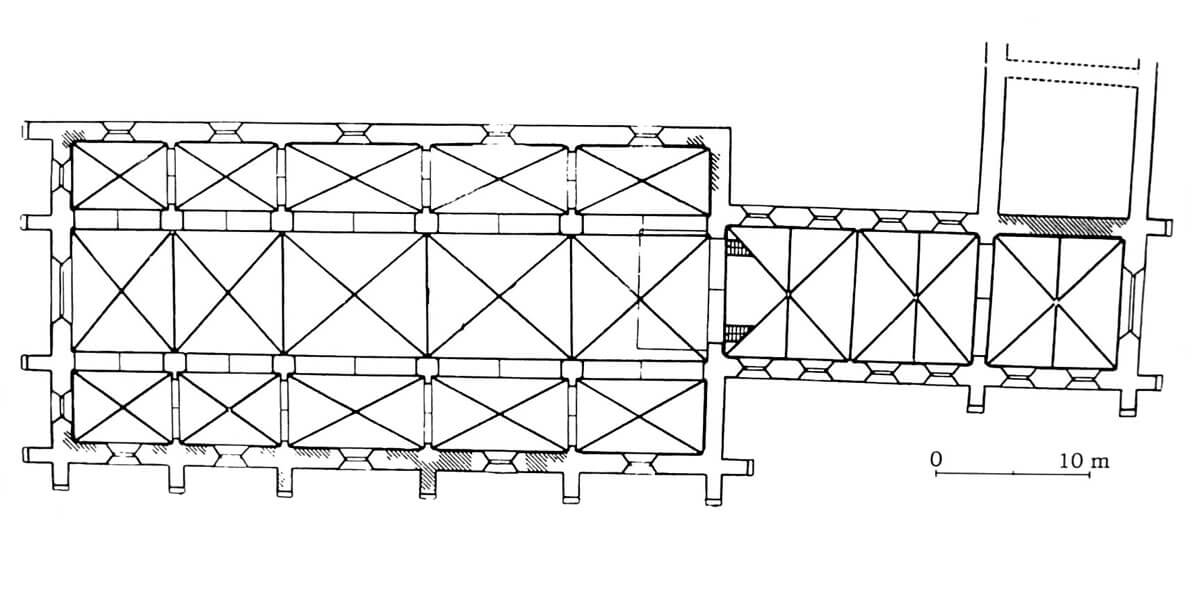

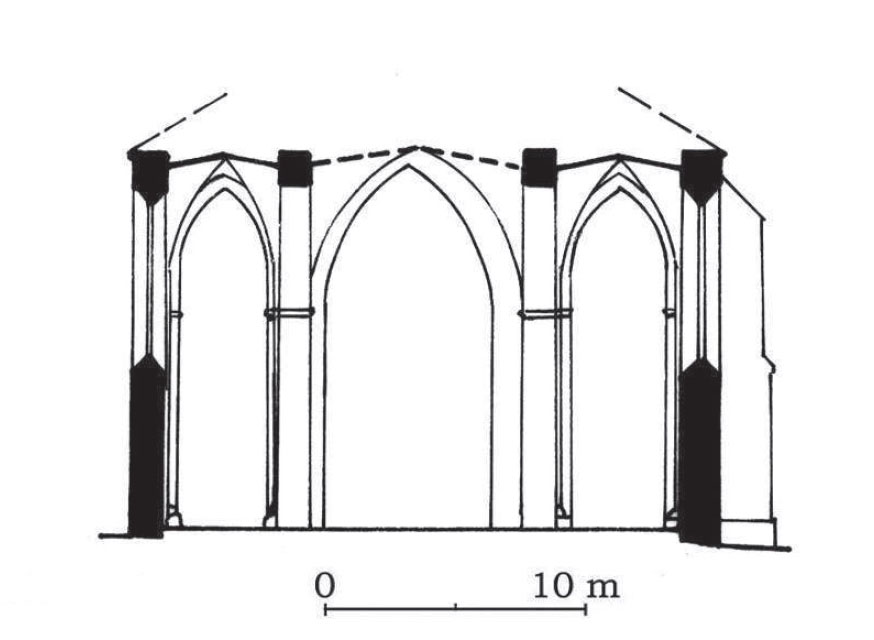

Initially, the Franciscan church from the 13th century was a three-aisle building of a hall arrangement with a narrower but long chancel, ended in the east with a straight wall. The church’s façades (apart from the northern one) were fragmented with buttresses, while in the corners they were led on the extension of the walls, not diagonally. Windows were pierced between buttresses, probably pointed and narrow.

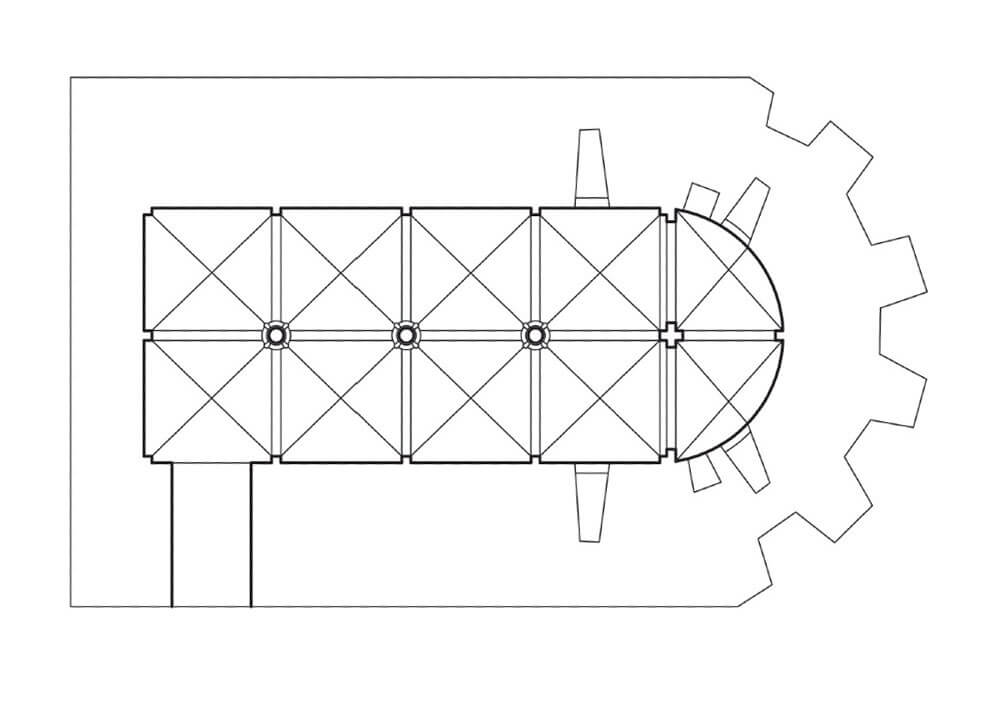

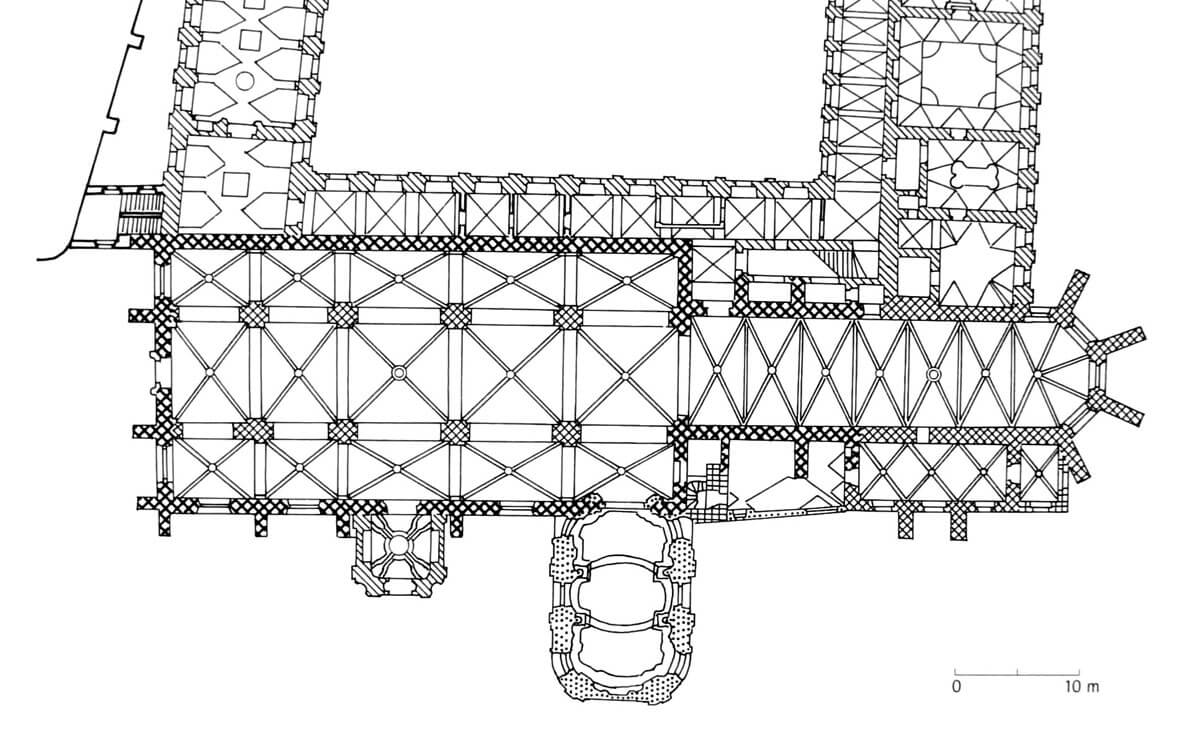

The presbytery part with interior dimensions of 8.5 x 22 meters had three bays of six-part vaults, with the eastern bay additionally separated with an arch band. The corner wall-shafs of the vaults went down to the floor, and the intermediate wall-shafs were hung on the corbels. There were two portals in the north wall: one led to the sacristy and the other to the friary courtyard.

The nave of the church with interior dimensions of 20 x 40.1 meters was divided into five bays. Unusually three eastern bays of the central nave were built on a square plan, and the other two were rectangular and shorter than the eastern ones. The cross vaults of the nave were based on inter-aisle pillars and wall half-pillars with wall-shafts. The chancel and nave were separated by a rood screen, based on a wall standing in a chancel arch and on pillars protruding towards the nave. In the eastern bay of the southern aisle there was a wide arcade, originally leading to the chapel. There were probably two entrances to the nave: from the west and from the south.

The late Romanesque crypt received five bays measuring 11.5 x 4.4 meters and a height of 1.7 meters. It was divided by pillars into two aisles, and the last bay went beyond the chancel arch to the west. Its lighting was provided by two windows located in the apse. The interior of the crypt, covered with rib vault, mounted on arch bands with pilaster strips descending directly to the floor, had a raw brick decor, only the granite capitals were decorative.

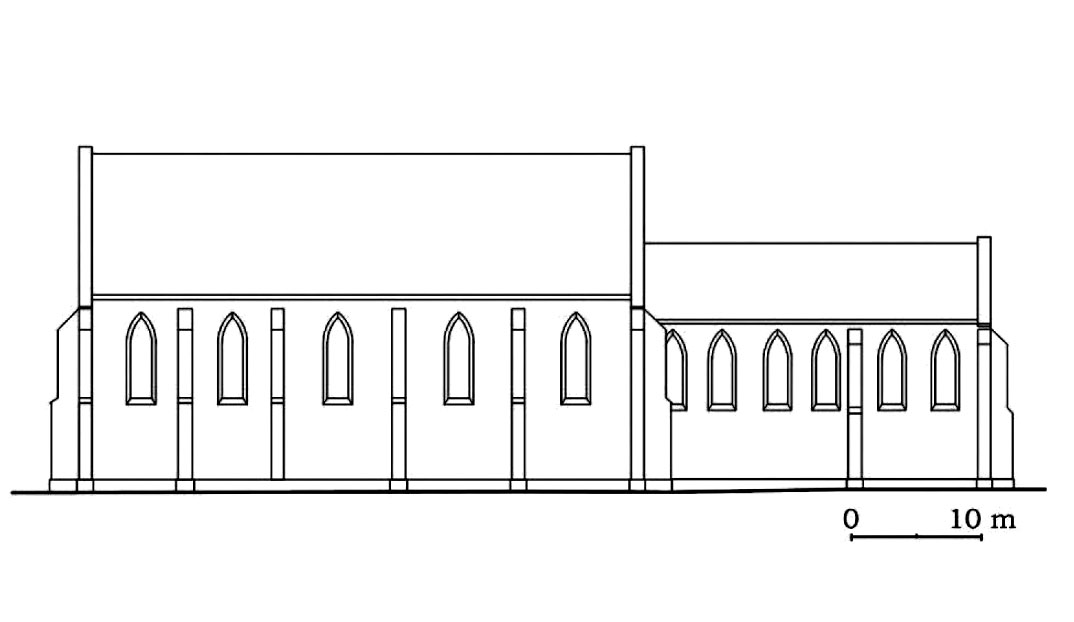

After the reconstruction from the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the church consisted of a three-aisle, five-bay basilic nave, which two western bays were still a bit shorter and of a six-bay chancel, five-side ended. Its dimensions after enlargement were 8.5 x 33.2 meters. In the southern corner of the chancel and the nave, a square tower was erected, going into the octagon above the roof ridge and topped with a high spire helmet. Outside, the church was covered with stepped buttresses, which were crowned with pinnacles in the closing of the chancel. The presbytery and the nave were covered with gable roofs, while the aisels were covered with mono-pitched roofs. The windows in the presbytery and in the aisles received larger jambs, originally ogival, three-light with tracery. Inside, the church was covered with rib vaults supported on octagonal pillars.

The internal façades of the church, including the pillars, were covered in the Gothic period with a light gray, almost white solution of milk of lime, probably in order to unify the face of the walls undergoing multiple reconstructions. In places where black zendrówka heads were placed, the entire surface was tinted with dilute red, which did not hide the texture of the bricks, but masked the unevenness of less careful joints and less well-burnt bricks. A network of thin white joints, made of lime milk, was painted on such a base. However, the most important decorative role was played by the concave moulding of pilaster strips, arcades and vaulting steps painted with thick red paint. It emphasized the divisions and form of Gothic architecture, completing the whole composition. An additional decoration were metal, gilded and blue-painted stars on the vault, covering regularly spaced openings left over from the scaffolding used during construction.

The buildings of the Franciscan claustrum were located on the north side of the church, which resulted from the terrain conditions, namely the only convenient access to the church was from the south, and from the north the monastery area was limited by the river. Initially, in the 13th century, the Franciscan buildings probably had the form of several free-standing buildings scattered around the courtyard, or a fenced square, without a cloister. Only in the 14th century, and at the latest in the 15th century, the claustrum formed a typical quadrangle of buildings with roofed cloisters running around the inner garth. It was surrounded by numerous economic and auxiliary buildings, adjacent to the city defensive wall, fenced together with the buildings of the Poor Clares.

Current state

The friary church, preserved to this day, is predominantly Gothic, rebuilt from the destruction of the Second World War, and has been renovated in recent years. The foundations of the walls and supports of the crypt, currently hidden under the church floors, have largely survived from the oldest late-Romanesque church. Traces of pilaster strips and parts of their bases from the 13th century have been preserved in the chancel walls. The tower, the southern wall of the chancel and the collapsed vaults had to be rebuilt among Gothic elements. The Baroque Hochberg chapel and the southern porch are attached to the church. Neither the rood screen nor any elements of the church’s medieval furnishings have survived (the tombstone of Prince Henry the Pious is in the National Museum in Wrocław). What’s more in 1991 the interior was wrongly painted, with the heads of bricks colored black, the joints white and the rest brick-red, which created the facades that never existed in the church or even in Silesia in the Middle Ages.

The monastery buildings on the northern side of the church were completely transformed in the early modern period, only relics of a brick wall were discovered in the monk bond in the eastern wing, along with the remains of a Romanesque portal (base of side columns). In the adjacent room, relics of late medieval wall paintings have also been preserved. More of the medieval remains of the friary are probably hidden under Baroque plaster.

bibliography:

Antkowiak Z., Kościoły Wrocławia, Wrocław 1991.

Brzezowski W., Małachowicz E., Kościół z klasztorem Świętego Wincentego we Wrocławiu, Wrocław 1993.

Kozaczewska H., Średniowieczne kościoły halowe na Śląsku, “Kwartalnik Architektury i Urbanistyki”, 1-4, Warszawa 2013.

Kozaczewska-Golasz H., Halowe kościoły z XIII wieku na Śląsku, Wrocław 2015.

Pilch J., Leksykon zabytków architektury Dolnego Śląska, Warszawa 2005.

Wojciechowska G., Zgraja A., Kościół pw. św. Jakuba we Wrocławiu w świetle wybranych badań architektoniczno-archeologicznych z lat 1947–1991 [w:] Dziedzictwo architektoniczne. Rekonstrukcje i badania obiektów zabytkowych, red. E.Łużyniecka, Wrocław 2017.