History

Uniejów, the property of the archbishops of Gniezno, appeared in documents as early as 1136, in the bull of Pope Innocent II. Probably there was a bishop’s court there, where in 1170 the bishop of Płock, Lupus, was consecrated by Archbishop Piotr. This court was recorded in 1242 (“curia sua apud Unyeyow”). In the following years, Prince Leszek the Black and Archbishop Jakub Świnka often stayed there. In the times of the latter the town of Uniejów was founded nearby. Both the town and the bishops court or the wood and earth castle (“dictum locum de Uneyow et eius castrum”), were destroyed by the Teutonic Knights in 1331. The damages were probably quickly repaired, because in 1339 a trial against the Teutonic Knights and a congress of secular and clergy dignitaries took place in Uniejów. The invasion also had a positive impact on Uniejów, because after the destruction of the stronghold in nearby Spicymierz, its importance increased. Moreover, it was the center of one of the richer estates of the Gniezno archbishopric, which was supposed to guard and also served as the seat of the archdeaconry and officialdom.

The brick castle was built in Uniejów around the middle of the 14th century on the initiative of the archbishop of Gniezno, Jarosław Bogoria Skotnicki. The hierarch took up the archbishop’s stool in 1342 and from that time became famous among numerous foundations, as a perfect organizer and builder of churches and episcopal residences (among others, he was the initiator of the reconstruction of the Gniezno cathedral). By building defensive structures such as Uniejów, Jarosław also completed the construction action of king Casimir the Great. In addition to its military function, the castle also served an administrative and prison role under the management of archbishops’ starosts and burgraves. In 1376, a synod was held there to tax the clergy for the crusade against the Turks, in which a special envoy of Pope Gregory IX, Nuncio Nicholas, Bishop of Majorca, took part, with the participation of many clergy. In castle prison, among others, was the Gdańsk sculptor Hans Brand, imprisoned in 1485 for failing to fulfill the contract to complete the Gniezno tomb of St. Adalbert. Perhaps religious opponents, Hussites or Arians, were also held in the castle.

Uniejów Castle was periodically a shelter for the cathedral treasury and archive, which were taken out of endangered areas in times of threats and wars. The fact that even then the treasures were not completely safe is evidenced by the fact that the castle was plundered in 1381. When the then administrator of Uniejów was murdered in Dąbie near Łęczyca, the Kruszwica provost Pełka of Garbów, his brother Bernard, who had been left on guard, upon hearing of the provost’s death, contrary to his earlier promises, occupied the archbishop’s seat and held it for two weeks, robbing the treasury and the entire herd and stud. He only gave up the castle when he received written guarantees from mediators and a waiver of claims to all the stolen goods.

In the first half of the 15th century, the castle was significantly expanded. This work may have been initiated by Archbishop Wojciech Jastrzębiec or his successor Wincenty Kot of Dębno. After 1435, Wincenty employed Grzegorz of Osik, a master of the art of cannon (“in arte pixidaria magistrum”), who remained in the service of the archbishops until at least 1455 and could have supervised part of the construction work in Uniejów. However, a more important reason for the reconstruction may have been the desire to enlarge the living space of the initially not very large castle. The work was probably completed before the outbreak of the Thirteen Years’ War in 1454, because the Gniezno chapter decided at the beginning of the conflict to transfer its priceless treasures to the Uniejów castle (“propter vigentes gwarras in terris Prussie in Unyeow pro conservacione deductis”). The Gniezno valuables were again deposited in Uniejów in 1478, when Canon Marcin of Niechanów took away the relics, richly decorated books and other valuable objects, and then gave them to Mikołaj of Sienno, the captain of the Uniejów castle. Often accumulated wealth in the castle could have been one of the impulses for its capture in 1492 by Wawrzyniec Kośmider Gruszczyński, during the war of the Gruszczyński family with Archbishop Zbigniew Oleśnicki over Koźmin.

Entrusting the castle to administrators sometimes led to problems, despite the taking of oaths about the later voluntary return of the assets. In 1422, after the death of Archbishop Mikołaj Trąba, Marcisz, the starost of Łowicz Castle, and Franczek, the starost of Uniejów Castle, did not want to voluntarily return the strongholds, probably in connection with the unpaid debts of the deceased. In order to regain the building, the chapter authorized its representatives, Przedwoj of Grądy and Mikołaj Jarocki, to offer 200 fines in exchange for the castle during the negotiations. The Gniezno canons had to face further problems after the death of Archbishop Jan Gruszczyński, when his brothers Bartłomiej and Mikołaj tried to seize as much of the archbishop’s estate as possible.

The good condition of the castle and neighbouring estates was ensured by numerous privileges, under which millers or village heads provided appropriate specialists. For example, in 1404, Archbishop Mikołaj of Kurów, when granting the village office of Smulsko to the bricklayer Jan, reserved his and his descendants’ help in renovating the castle in Uniejów. A similar obligation was imposed on the miller Jan Chodawa by virtue of Mikołaj Trąba’s privilege. Wincenty Kot, when giving Jakub the carpenter permission to build a mill, obliged him, among other things, to repair and prepare furnitures, while Jakub of Sienno in a privilege for the miller Maciej of Warta, reserved for himself “laborare in castro et mensas perficere”.

In 1525, Uniejów Castle was destroyed by fire. Reconstruction combined with the transformation of the buildings took place in 1534, on the initiative of the starost Stanisław of Gomolin. Further, early modern construction works were carried out by archbishops Jan Wężyk and Maciej Łubieński in the first half of the 17th century, which ultimately changed the castle into a Renaissance-Baroque residence. After the secularization of church property at the end of the 18th century, a significant part of the castle was abandoned and only in 1836 the tsarist government handed it over to General Aleksander Toll, who renovated it in 1848. In the interwar period, a guesthouse operated in the monument. After the war damage from World War II, the devastated castle was rebuilt only in the years 1956-1967.

Architecture

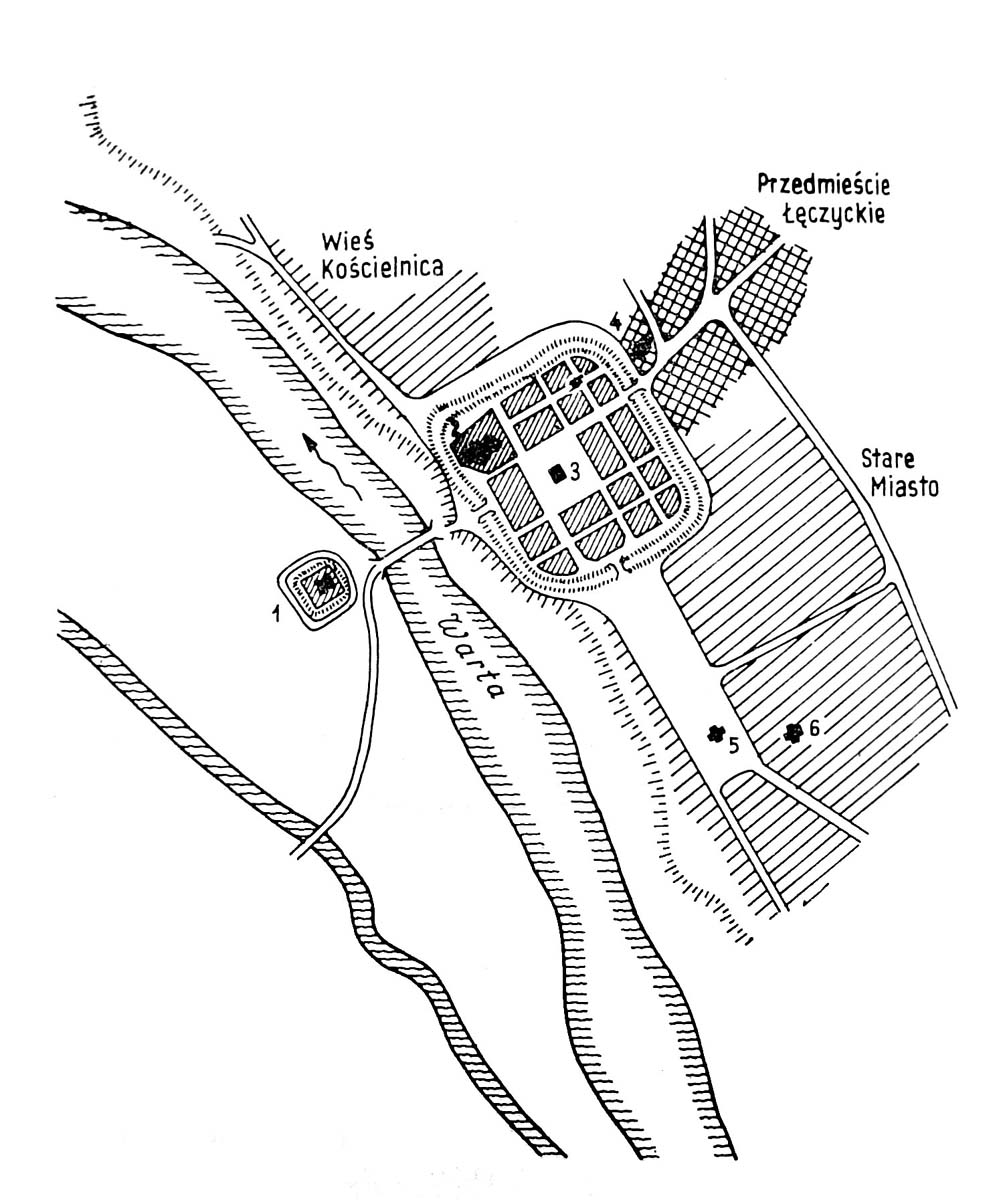

The castle was situated on the left bank of the Warta, on a small elevation on the western side of the riverbed. On one side it was secured by the river, which came almost to the very building, and on the other sides by marshy and boggy areas and smaller branches of the Warta. In addition, a moat was dug as an external defence zone. The only communication connection with the town was provided by a nearby bridge, probably of wooden construction in the Middle Ages. Its protection on the opposite side of the castle was provided by the wood and earth fortifications of the town.

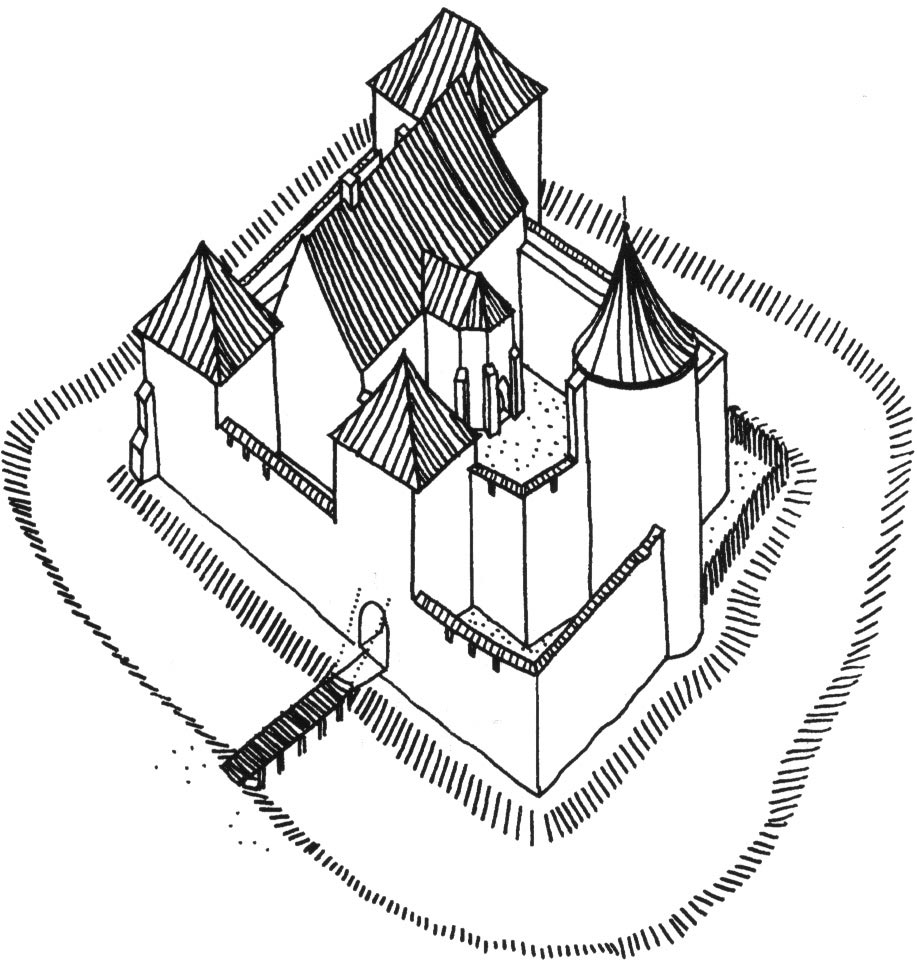

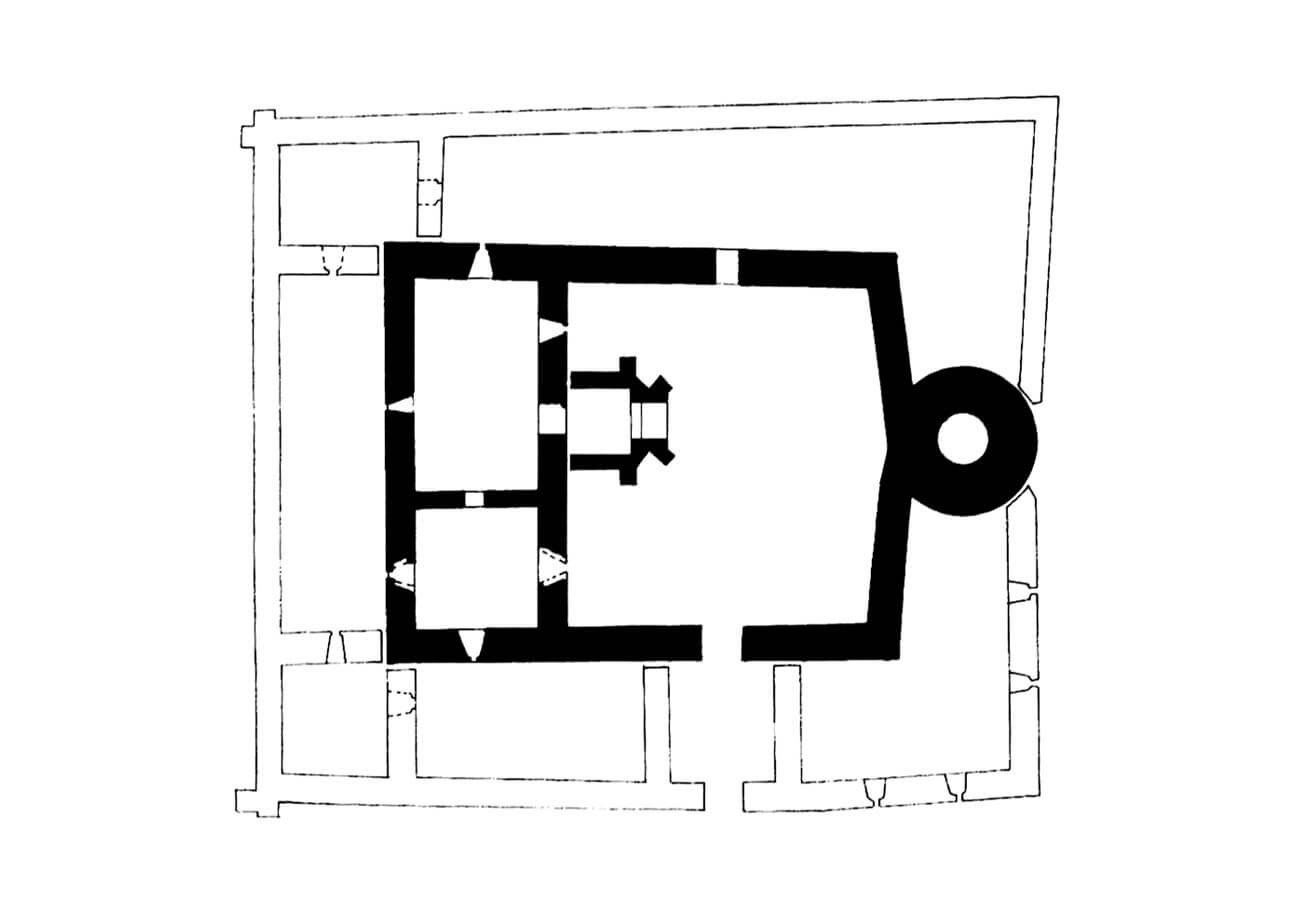

In the 14th century, the castle consisted of a quadrangular circuit of walls measuring 23 x 29 meters and about 13 meters high, built of bricks in the Flemish bond, on a stone foundation joined with lime mortar. A gateway was located on the south, and on the west side of the cobbled courtyard, a three-storey residential house measuring 10.5 x 23 meters was built, three walls of which were also part of the defensive circuit. On the ground floor, it was divided into two rooms: a larger northern one and a smaller southern one on a square plan. The building was enlarged by a chapel, protruding its entire circumference towards the courtyard (perhaps based on the chapel in the Poznań castle), orientated with a polygonal closure of the chancel to the east. The residential rooms on the first floor of the house could have been connected with a walk in the crown of the walls, the finial of which probably had the form of a parapet with battlements.

The main tower with a diameter of 9 meters was erected outside the wall in the middle of the eastern curtain. Due to the high altitude (35 meters), it was reinforced with three buttresses, and originally the only entrance to it was located at a height of 13 meters above the level of the courtyard and was accessible by a footbridge from the crown of the defensive wall. Vertical communication was provided by a spiral staircase placed in the north-west buttress, but it was not directly connected with the entrance, because it started at a height of 4 meters above the floor and led to a defensive level at a height of 25 meters.

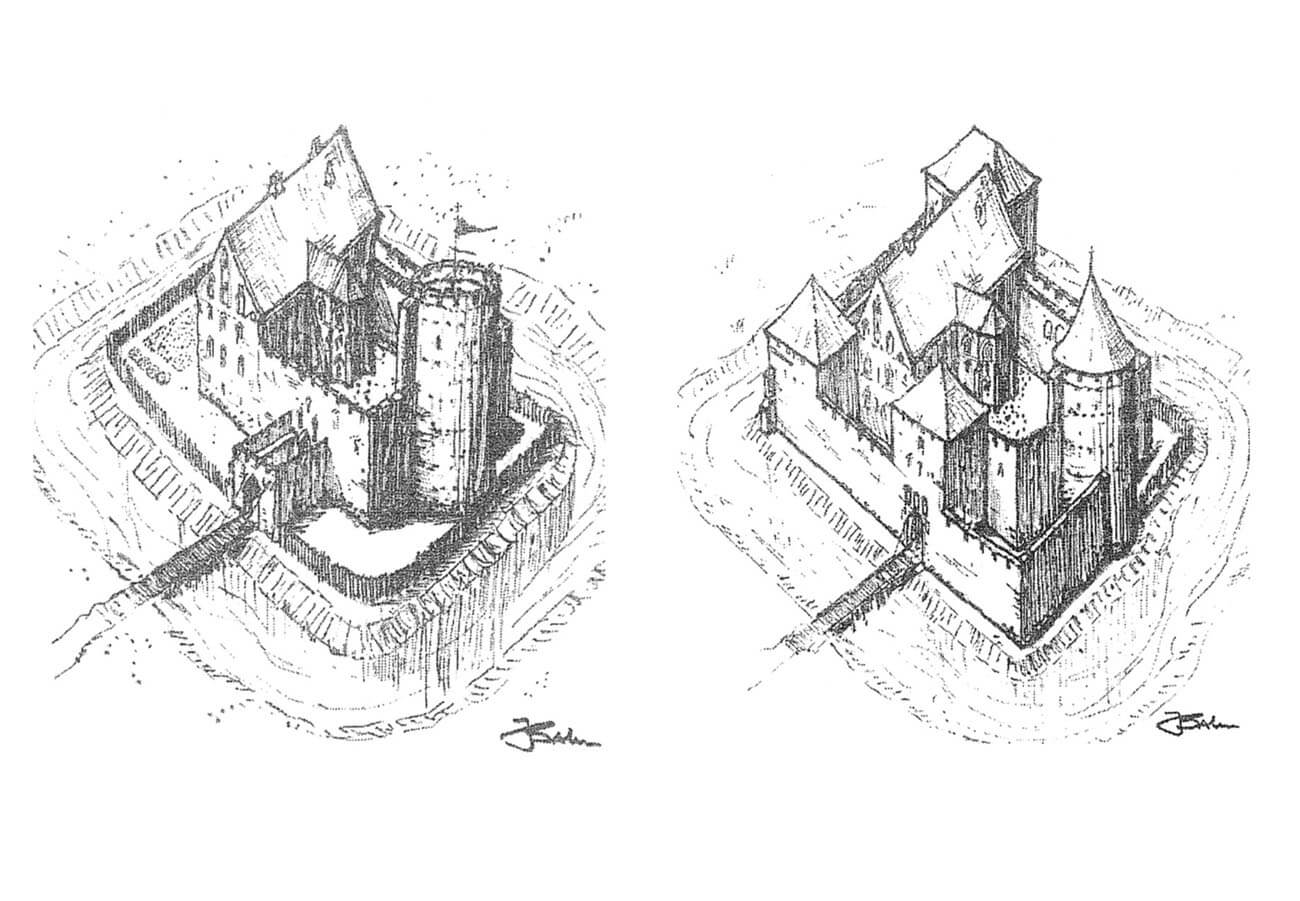

Around the middle of the 15th century, two quadrilateral, three-story residential towers were added to the main residential house in the corners. They were connected with each other by an outer wall, closing the west zwinger. The rebuilding also included the southern part of the castle. A four-sided gate tower, connected by an external wall with a main tower, was built on the site of the former gate. The new fortifications separated about 6.5 meters width zwinger. Ultimately, the late Gothic expansion gave the castle one of the most interesting spatial layouts in central Poland, with a diversified body with numerous height dominants, and also with a relatively large residential and representative space.

In the first half of the sixteenth century, the south-eastern part of the zwinger was built up with a new residential building, which, having the shape of the letter L, reached the main tower, which was then raised by the next defensive level. On the north side, the new economic wing was adjacent to the tower, closing the whole castle in the shape of a regular quadrilateral. Communication between individual wings was provided by the inner courtyard. The south wall had two entrance portals: one to the gate tower and the other leading to the south zwinger. On the opposite side of the courtyard, on the axis of the main entrance there was a narrow passage to the northern zwinger. Three ogival blendes were visible above it. From the northern zwinger led the entrance to the cellars of the north-western tower and symmetrically to the opposite economic building. In addition, the upper storey of the main house was connected with the south-east wing through the porch on the wall and the gate tower.

Current state

Uniejów Castle, although it has survived to the present day in a heavily transformed form, has a clear medieval spatial layout and individual elements, including a Gothic main tower and a narrow, unplastered courtyard enclosed by a full circumference of a defensive wall. This makes it the best-preserved medieval building of the Gniezno archbishops, although the elevations are now pierced with large, regularly spaced windows, only the plinth remains of the castle chapel, and the zwinger on most of the circumference has been built over. Currently, the castle premises house a hotel with a conference center and a restaurant. The monument is open to visitors, but to a limited extent.

bibliography:

Krantz L., Zamek w Uniejowie, Poznań 1980.

Leksykon zamków w Polsce, red. L.Kajzer, Warszawa 2003.

Tomala J., Murowana architektura romańska i gotycka w Wielkopolsce, tom 2, architektura obronna, Kalisz 2011.

Uniejów. Dzieje miasta, red. J.Szymczak, Łódź-Uniejów 1995.

Wilk-Woś Z., Zamek arcybiskupów gnieźnieńskich w Uniejowie w XV wieku w świetle źródeł pisanych,”Biuletyn Uniejowski”, 4/2015.