History

The monastery with the church of St. Nicholas was built for the Dominican Order, brought to Toruń by the Teutonic Knights in 1263. At that time, they were provided by the Grand Master Anno von Sangerhausen with a building site located east of the mill stream. In another document from 1264, the Grand Master allowed the Dominicans to move to the originally indicated location, with the stipulation, however, that the brothers would not build their buildings too close to the Teutonic castle. It was probably not about moving in the literal sense, but about including the monastery plot in the area of the planned New Town of Toruń, which was officially founded a few months later.

The construction of the brick buildings of the friary, with the monastery church at the forefront, began no later than 1265, as evidenced by the forty-day indulgence granted by the Bishop of Chełmno, Frederick, which was supposed to bring income to finance the construction works. The Dominicans, despite having obtained the right to fish in all the rivers and lakes of Toruń, supported themselves primarily from donations from the town congregation. Another indulgence announced for the same purpose was issued a year later by the Bishop of Samland and Kuyavia, Wolimir, although construction work in 1266 had to be temporarily suspended by the Prussian invasion and the removal of damages after it. The first monastery church could have been ready before 1285, because in the indulgence issued that year by the Archbishop of Gniezno, Jakub Świnka, or in subsequent privileges of this type for the Dominicans of Toruń, there were no further calls for donations for construction works.

The erection of the most important buildings of the claustrum was probably completed in the late 1270s or in the 1280s, i.e. after the completion of the defensive walls of the New Town, to which the monastery buildings were adjacent. One of the duties of the Dominicans of Toruń was to build a section of the fortifications adjacent to the friary. This investment led to a conflict between the monks and the townspeople, and in 1279 the New Town took over the construction work in exchange for the delivery of building materials (which included 17,000 unfired bricks and 50 logs). The transport of large quantities of building materials by the monks would indicate that they no longer had any major needs for their own friary buildings.

Around the second decade of the fourteenth century, the Dominicans began building a new, more magnificent church. It is not known how long it lasted, only the indulgence letter of the bishop of Chełmno Otto from 1334 indicated that the choir and sacristy were not yet finished due to the financial problems of the friary resulting from the war. The bishop’s exhortations had to have the desired effect, because the new chancel was built before 1339, when Prior John the White committed himself to holding services for members of the Redzey family. In the following years, numerous altars were also recorded in written sources. Among others, in 1343, when the Sambian bishop granted an indulgence to the praying in front of the altar of St. Augustine. It is not certain, however, whether it was related to the completion of the construction of only the eastern part of the church or also the nave. It seems that the construction of the latter was carried out until the second half of the fourteenth century, until around 1383, when works of the cloister vaults adjacent to the church were recorded. The construction of vaults in a church or claustrum may have taken even longer, until the beginning of the 15th century, because in 1417 the account book of the city brickyard recorded an order from the Dominicans for as many as 42,500 bricks, including shaped bricks needed to build arches and vaults or architectural details of the gables.

The monastery buildings were damaged many times as a result of wars, fires and lightning strikes. The entire friary burned down in a fire in 1423, and in 1598 the church was struck by lightning. In 1648, it was necessary to renovate the side aisle and built vaults in three southern chapels. During the siege of the town in 1658, the area belonging to the Dominicans was shelled, while in 1685 a fire broke out in the church, destroying the new organ. Another war devastation took place during the siege of Toruń by the Swedes in 1703. In 1709, another lightning damaged the church and injured the people, and in 1764 a fire that broke out in the monastery buildings moved to the church. The next destruction was the result of the sieges of 1809 and 1813, after which the buildings were rebuilt for the last time. When the order was dissolved in 1820, in the following years the monastery buildings were demolished, the church was set up as a warehouse, and in 1834 it was finally pulled down.

Architecture

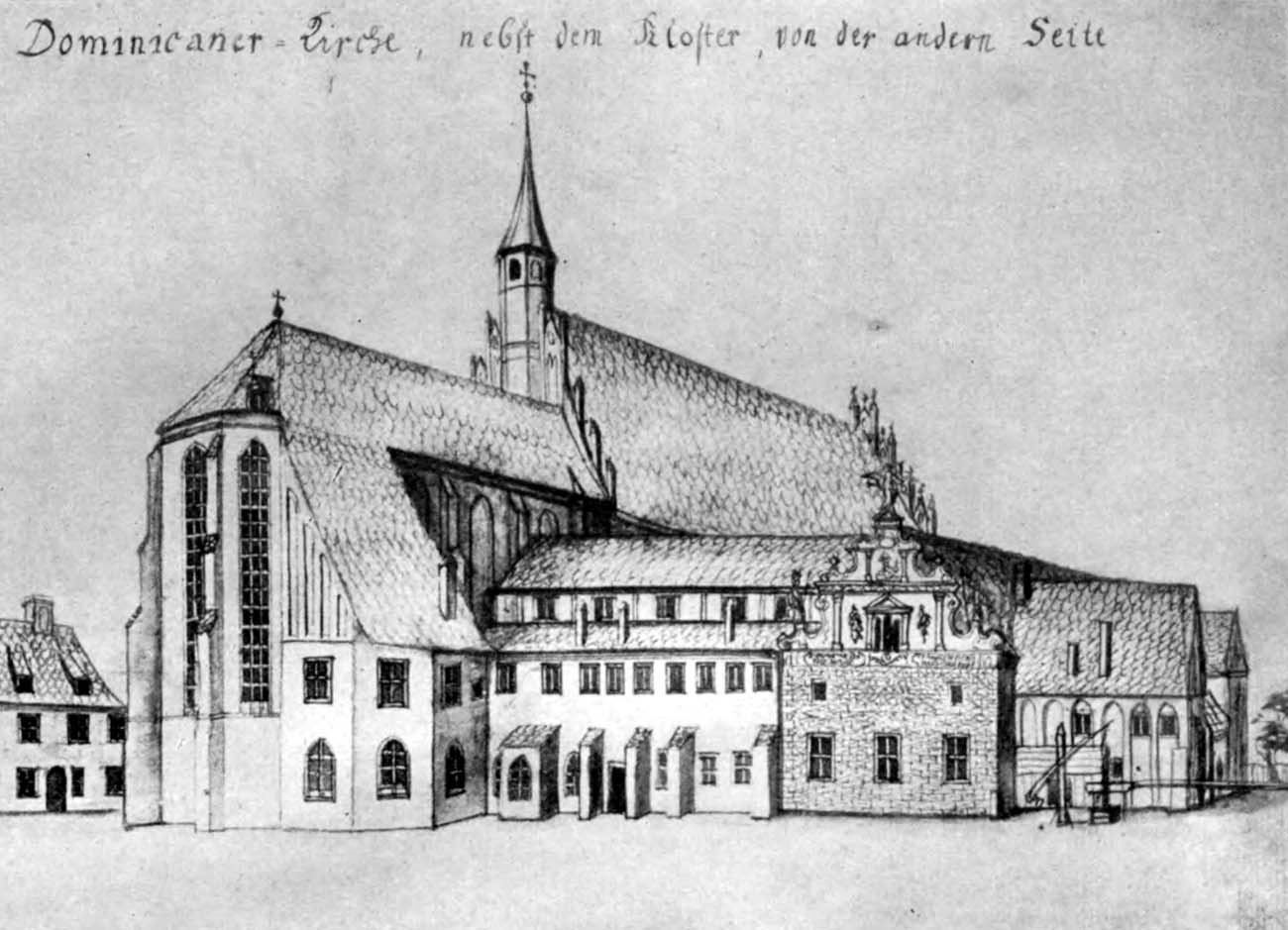

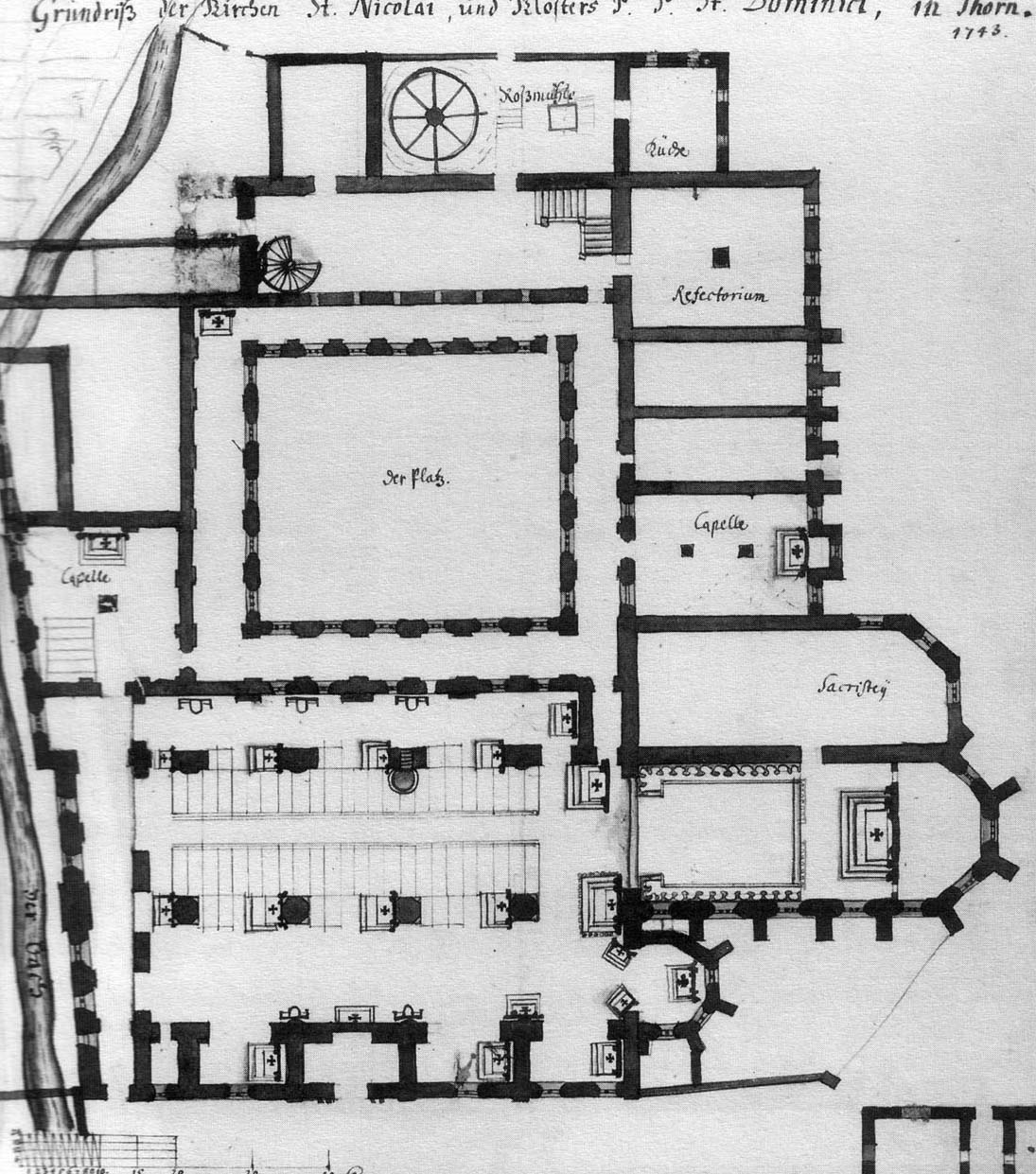

The friary was located in the north-west corner of the New Town of Toruń, in the immediate vicinity of the defensive walls, from the north facing the foreground of the town, and on the west side facing towards the moat, behind which was the line of the Old Town wall. The northern part of the complex was a courtyard surrounded by cloister and friary buildings, while the southern part was a monastery church, facing the southern façade towards a small square, with which the Pauline Gate connecting both Toruń towns was linked. The monastery area was separated from the streets and town buildings by a low wall.

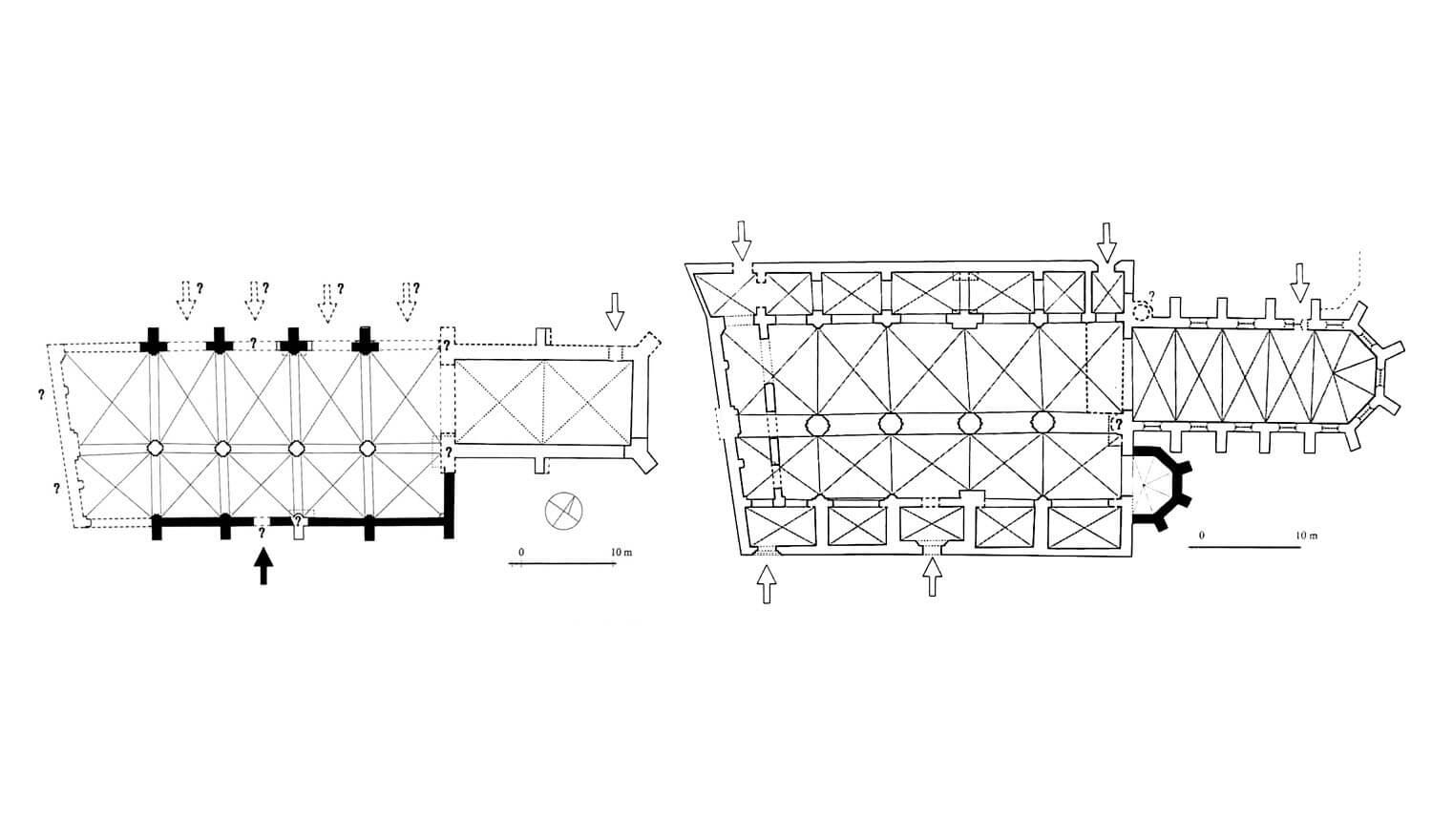

The oldest monastery church from the turn of the third and fourth quarter of the 13th century had a chancel with a straight eastern closure and diagonal buttresses in the corners. It probably had a rectangular plan of about 22 meters long and 12 meters wide, divided into two square bays. Such proportions would indicate the planning or installation of a two-bay cross-rib vault with subsequent single buttresses from the north and south. The nave, if completed at that time, probably had two aisles, although probably narrower and lower than the later one.

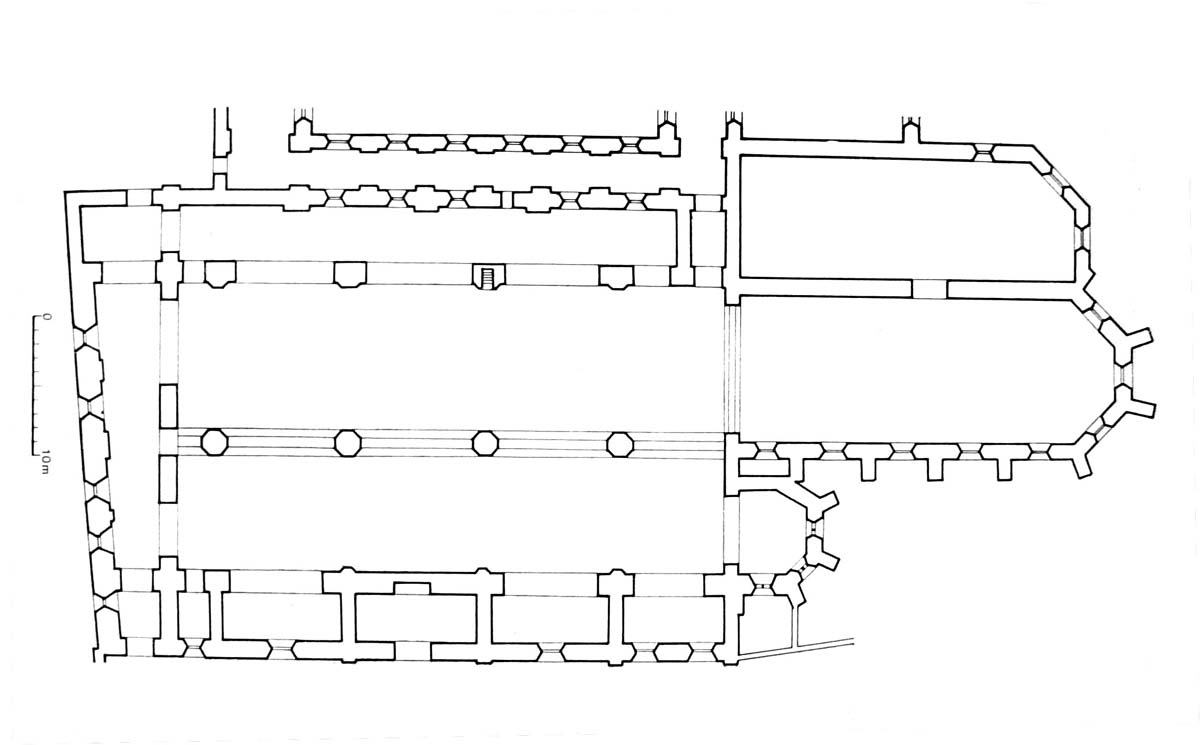

Around the second quarter of the 14th century, the church was rebuilt. It was still a two-aisle hall, but the chancel was extended and closed from the east in a polygonal manner. The new chancel was probably about 6-8 meters higher, so reaching a height of approximately 21 meters. In plan it was about 30.3 meters long and 13.2 meters wide, and it was placed on the axis of the northern aisle, not on the line of the inter-nave pillars. A Gothic gable was built over the chancel arcade, indicating that there were no plans to raise the nave of the church at that time. The northern aisle was about 46-49 meters long and had five bays. Both aisles could originally have been covered with separate gable roofs, and closed from the west with an unusual, diagonally led wall, due to the mill stream flowing there.

Since the church could not be expanded on the south side due to the street, in the second half of the 14th century the original northern wall of the nave was pierced and the former southern cloister of the convent was incorporated into the church, preserving its original height. This cloister was topped with a five-support vault, and after being incorporated into the church, it took the form of a series of interconnected chapels. A series of rectangular, low chapels was also added to the southern elevation of the church, where there were three chapels, a porch and a smaller side entrance. After the old cloister was incorporated into the church, a new one was built on the south side of the friary garth (on the north side of the church).

Probably at the end of the 14th century, it was decided to raise the nave of the church in order to level it with the slender chancel. The original inter-nave pillars were demolished. In their place more massive octagonal pillars were erected, which had to support the new vaults that were built much higher. The interior was better lit by means of tall pointed windows, the penetration of which from the south and west was of particular importance due to the blocking of the northern elevation with a row of chapels and a cloister. From the outside, the mass of the church was clasped with two-stepped buttresses reaching the crown of the walls, set more densely at the chancel than at the nave, and covered by chapels and a porch at the southern aisle. Additionally, from the east, the southern aisle was ended in the 15th century with a polygonal chapel of St. Jacek. In the middle of the eastern gable of the nave, an octagonal turret with a height of 49 meters was built, while the second gable decorated the nave from the west and closed one common roof over both aisles. The eastern gable was seven-axis, divided by blendes and pilaster strips passing into pinnacles. Each blende was crowned with a gable with a round wind hole. The western gable was similar but divided into nine axes, as it was not divided by a turret.

The interior of the church was distinguished by a considerable height of over 21 meters. In the nave this space was divided by the aforementioned four octagonal pillars with smooth shafts and finials in the form of stepped bands, supporting cross-rib or stellar vaults. The chancel could be divided into four rectangular bays with a cross-rib vault and a polygonal eastern bay with a sixpartite vault. The main aisle was separated from the chancel by a brick rood screen, situated on the axis of the eastern wing of the monastery. The rood screen marked the boundary between the part accessible to lay people (nave) and the part accessible only to monks (choir, presbytery). On its eastern side, along the walls, there were stalls with several dozen seats.

The factor influencing the irregular, two-aisle layout of the Dominican church in Toruń, similarly to other Mendicant churches throughout Europe, was the limited size and shape of building plots. Dominicans and also Franciscans were usually brought to already functioning towns, which made it usually impossible to obtain a full, regular land for development. In addition, the ground was often received piece by piece at considerable intervals, which naturally influenced the complex construction history. At the origins of the Mendicant, asymmetrical two-aisle churches, there were also buildings that originated from semi-secular architecture. The oldest two-aisle halls adapted for liturgical purposes the type of interior that previously appeared mainly in refectories, chapter houses and hospitals (eg the Dominican church in Paris transformed from the hospital of St. James). The last important reason for the irregularity of the churches could be the deliberate abandonment of regular, spatially ordered plans by the Mendicant monks. It could have been a deliberate demonstration, a manifestation of architectural modesty (as well as the limitation of the vaults’ shafts and the preference for smooth, inarticulate planes of the walls), showing that the monks did not care about the traditional monumentality of their churches, which were to be primarily functional, and only impressive in terms of mass.

The monastery buildings surrounded with cloisters on the northern side of the church a quadrilateral courtyard. The entire length of the chancel was adjacent to the sacristy, and between them there were two more small rooms interpreted as penitential cells. Further to the north there was a two-aisle chapel, perhaps the original chapter house, above two similar elongated rooms, of which one had passages, and in the corner of the eastern and northern wings, a square refectory. It adjoined the kitchen and other rooms of the northern range and the mill. In the west wing, located closest to the mill stream, there had to be latrines, while its southern part was the chapel of St. Catherine, illuminated by three large pointed windows.

Current state

Dominican friary and St. Nicholas’church, apart from a few relics and fragments of the foundation walls, unfortunately, has not survived. It was undoubtedly one of the most interesting Gothic sacral buildings in the Chełmno region, therefore its senseless demolition in 1834 is a great loss not only because of the importance of the friary for the history of the town, but also because of its monumental, complex and interesting form that shaped the former Toruń.

bibliography:

Adamski J., Kościół dominikanów w Toruniu i niesymetryczne korpusy mendykanckie w Środkowej Europie [w:] Dzieje i skarby dominikańskiego kościoła pw. św. Mikołaja w Toruniu, red. K. Kluczwajd, Toruń 2017.

Grzeszkiewicz-Kotlewska L., Kotlewski L., Kościół dominikański pw. św. Mikołaja w Toruniu, Toruń 1997.

Herrmann C., Mittelalterliche Architektur im Preussenland, Petersberg 2007.

Mroczko T., Architektura gotycka na ziemi chełmińskiej, Warszawa 1980.

Samól P., Architektura kościołów dominikańskich, Gdańsk 2022.