History

The settlement of Strzelce first appeared in documents in 1234 and next in 1271. Before the construction of brick buildings, there was probably a timber stronghold and a small hunting manor there, from which people traveled to the dense forests covering the surrounding areas. The name of the stronghold itself would indicate that it was the seat of the prince’s archers, guarding on an important trade route connecting Kraków and Wrocław. The town, which grew on the site of a stronghold, relatively quickly became an important center thanks to its convenient location. It was probably founded during the rule of Bolko I of Opole, who died in 1313. This ruler also contributed to the construction of a brick castle at the end of the 13th or early 14th century. It was first recorded in 1303 as “castrum Strelecense”.

In 1323, when the son of Bolko I came of age, the Duchy of Strzelce was separated from the Duchy of Opole, and Strzelce became the seat of an independent ruler, Albert. This prince surrounded the town with walls (first recorded in 1327), which were connected to the castle. He took care of the development of his capital, endowing it with Magdeburg charter, enriching it with the privilege of collecting fees from passing merchants, and conducting an active international policy. He strengthened relations with the Kingdom of Hungary, among others by sending envoys on behalf of King Louis to the Pope in Avignon and to the King of Poland, Władysław the Elbow-high, with whom he was related. Thanks to this, the town and the castle were away from any disputes and wars. After Albert’s death in 1370, the duchy together with the Strzelce passed to the Piast dynasty of Niemodlin, and after their die out, in 1382 to the princes of Opole.

During the Hussite Wars and the invasion of 1430, the castle and town did not suffer, due to the intercession of pro-Bohemian prince Bolko IV of Opole. Also, no damages occurred during the passage of Polish troops of prince Kazimierz towards Prague. In the later fifteenth century, the castle was rebuilt, and after the death of the last prince of Opole, Jan II the Good in 1532, it became the property of the Czech king Ferdinand Habsburg. Two years later, it was pledged to Georg Hohenzollern-Ansbach. On this occasion the urbarium was written down, according to which the castle was in a bad technical condition and required urgent renovation.

In 1562, Strzelce was leased by the Redern family. Georg von Redern began a long renovation and Renaissance reconstruction of the castle, which lasted almost until the end of the 16th century. After Georg, George II von Redern also held the pledge of Strzelce, and in 1615 he bought the local estates as his own. In the second quarter of the 17th century, the castle and the town passed to the Collon family through marital affinity. Subsequent generations of this family used and transformed the castle into an early modern palatial residence until 1807. In the 19th century, it was owned by successive great Silesian families, who adapted the buildings to their preferences. The last major reconstruction of the former castle took place in the middle of the 19th century. During World War II it was burned and then left in ruin.

Architecture

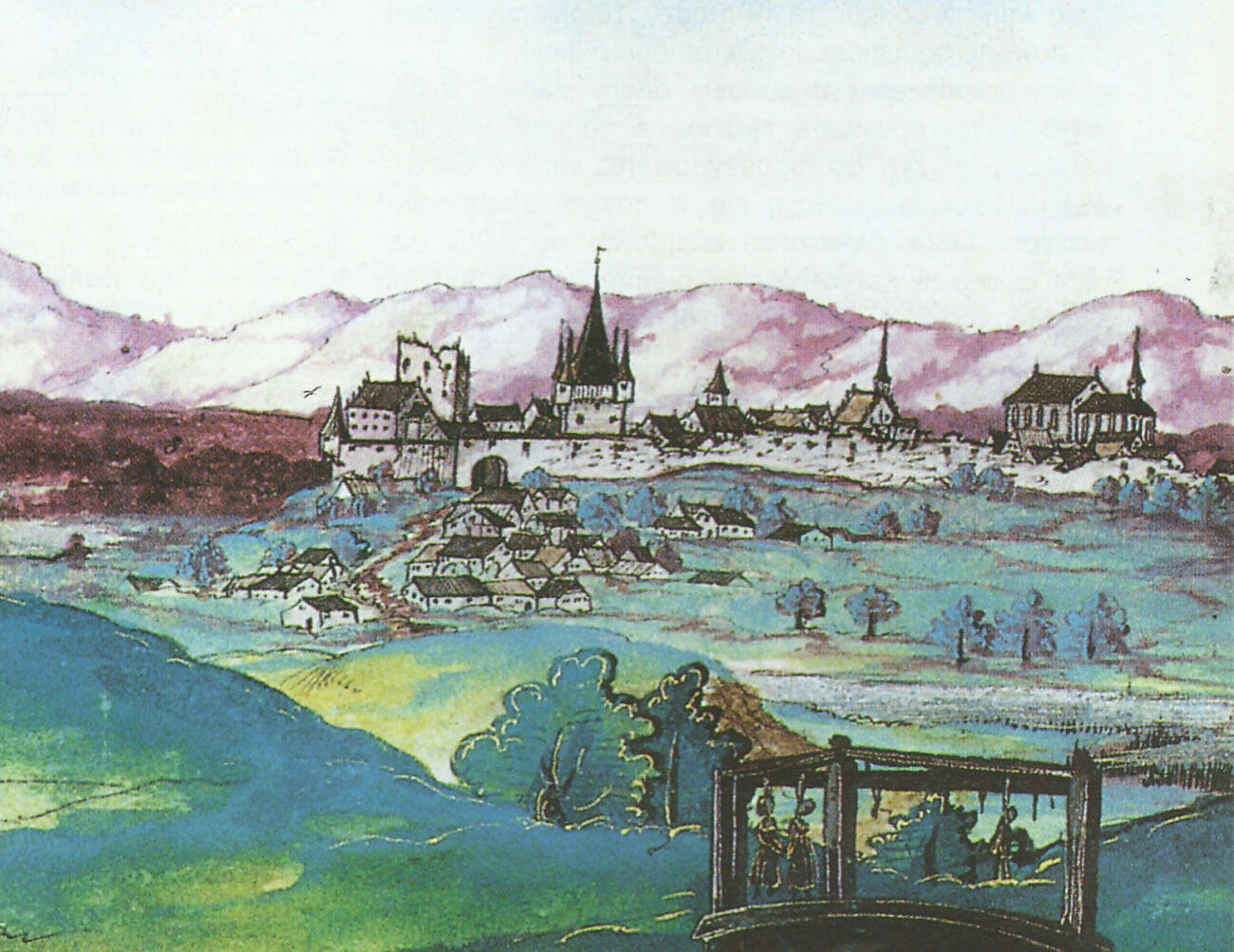

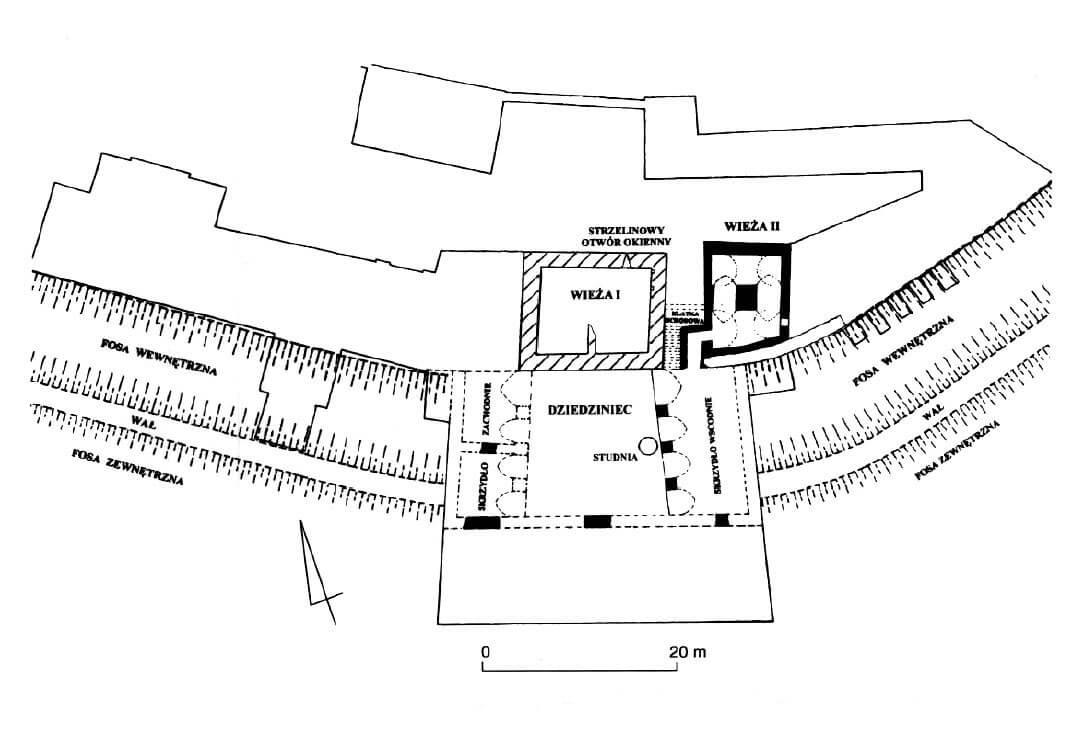

The castle was located in the southern part of the town, near the Strzelce defensive wall, connected to the castle from the east and west. From the south, the castle and the town were protected by marshy and swampy areas marked by numerous streams. Plan of the charter town had a shape close to oval, with a narrowing in the northern part surrounding the parish church. The main routes led to Strzelce from the east and west, along the route connecting Wrocław with Krakow. To the north of the town there were vast forest complexes.

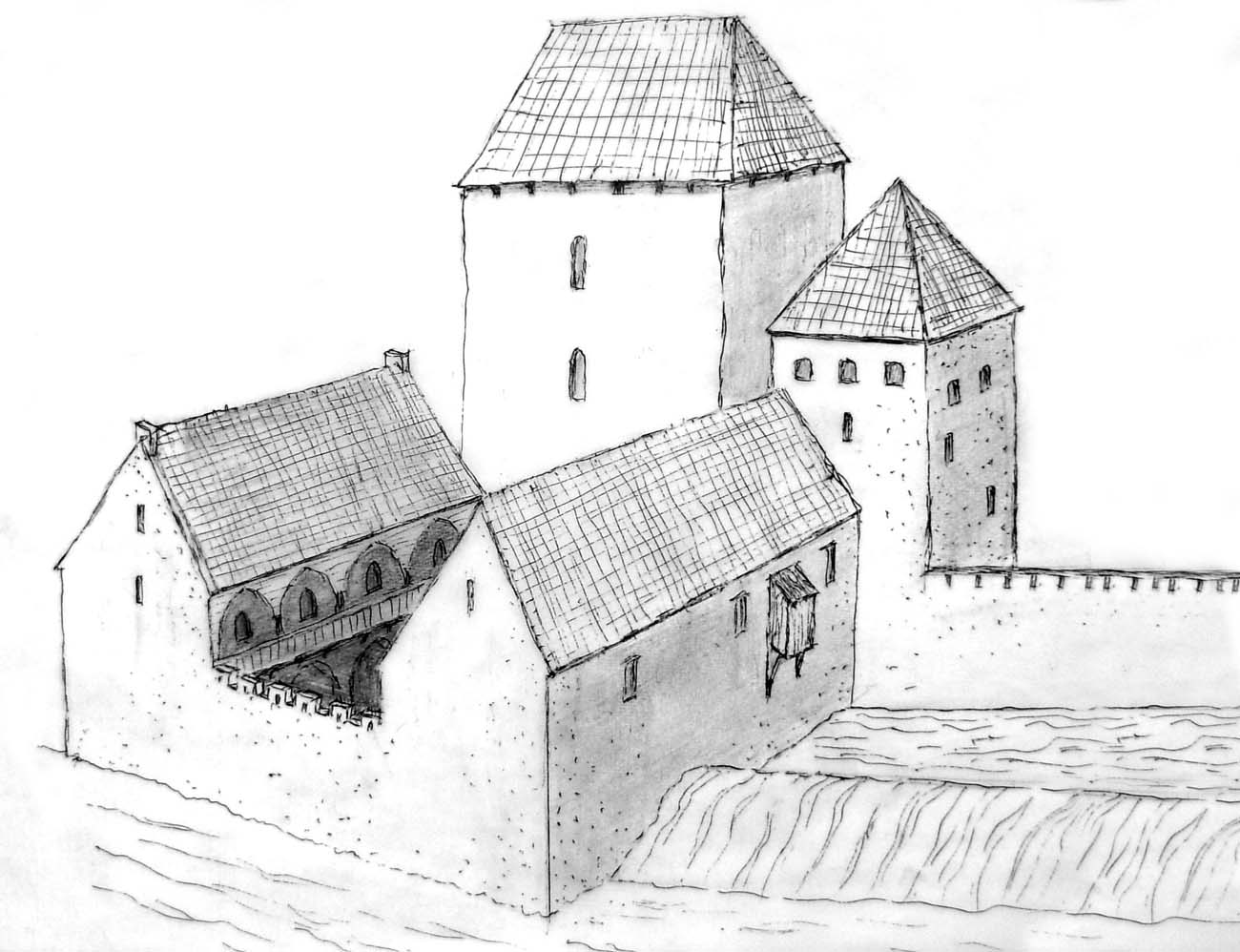

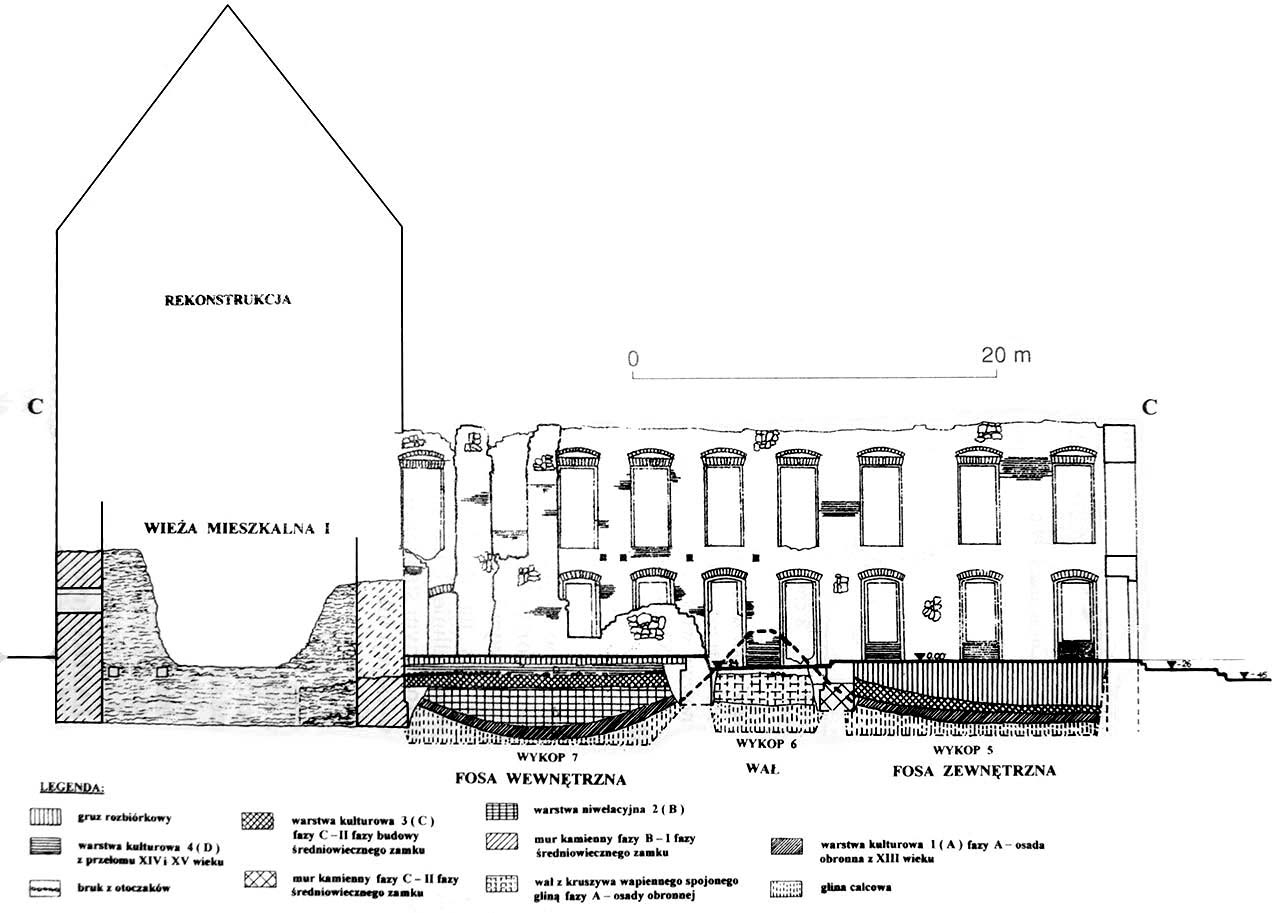

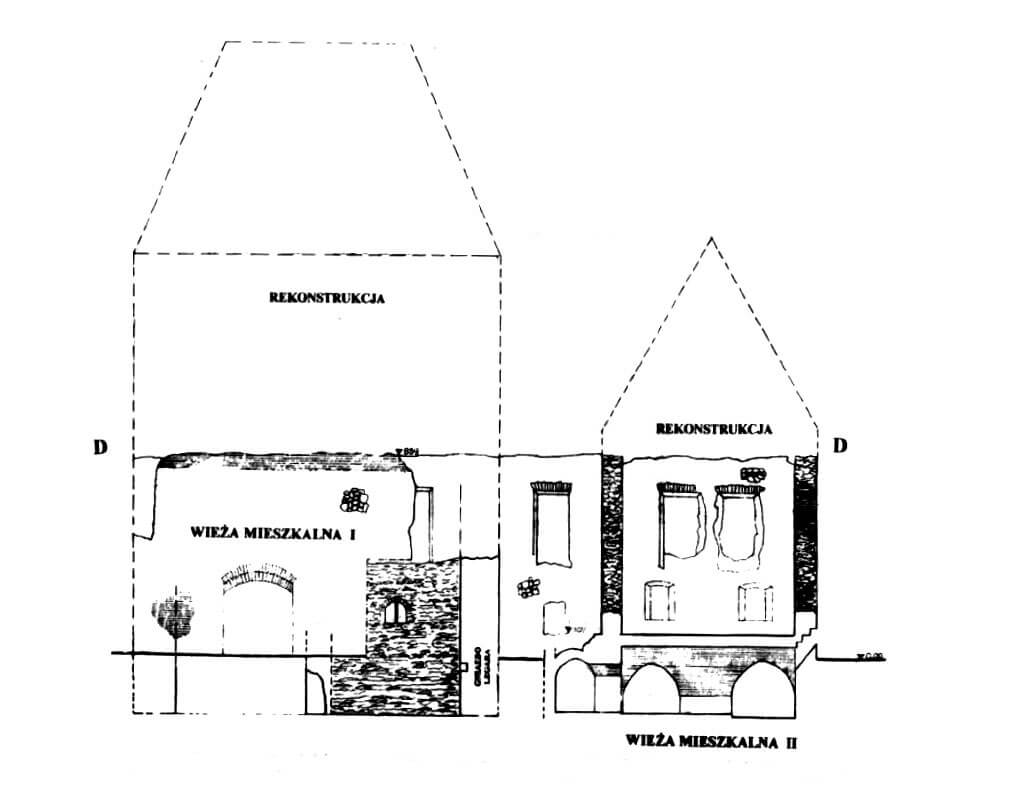

Main and oldest element of the castle, dating to the second half of the 13th century, was a four-sided tower, built of limestone tiles, sand-lime mortar-bonded. It was a residential building with dimensions of 13.9 x 16.1 meters. The thickness of its walls was not very large, as it ranged between 1.7 and 1.8 meters, while the height can be estimated on the basis of comparisons to other buildings of this type at about 17 meters. It was probably covered with a hip roof with a ridge. The interior was two-space, divided symmetrically by a partition wall running transversely to the long axis of the building. The floors were separated by wooden ceilings, and the lowest level was illuminated by slit opening 9 cm wide and less than a meter high, embedded in the frames widely splayed inwards (such a opening has survived in the northern wall of the eastern room). Vertical communication was probably provided by a spiral staircase embedded in the thickness of the wall (mentioned in 1534).

The two southern corners of the tower touched the defensive wall, which was probably not a town wall, but a wall delimiting the small courtyard of the ducal estate. From the southern side, the castle was protected by an earth rampart, 7 meters wide, surrounding the entire town on the section from the Kraków Gate to the Opole Gate. There were two lines od ditches on the outer and inner sides of the rampart, although the areas were swampy and difficult to access. Their width was not less than 10-11 meters, while the depth was about 2.7 meters from the crown of the rampart. The earth walls were the remains of an older stronghold, perhaps associated with the Lusatian culture population.

The town wall was 900 meters long, covering an area of approximately 5.7 ha. It was built of local, flat limestones. Its core was made of rock fragments plentifully poured with lime and sand mortar. The wall thickness was from 0.9 to 1.3 meters, and the height was over 6 meters. Active defense was provided by porches placed in the crown, supplemented by at least one open half-tower in the south and closed tower in the north-eastern part of the town, near the church of St. Nicholas. The closed tower had at least 9 meters above the ground level. In addition to military functions, it may also have been a dominant feature in the northern part of Strzelce, representing a visual and symbolic counterbalance to the castle. The defensive wall was preceded by a moat, which in the north-eastern and eastern parts was fed with water from a nearby stream. Two gates led to the town, both in the form of small buildings erected on a square plan.

Around the first quarter of the fourteenth century in order to allow the castle to be expanded to the south, an internal ditch was filled up to the middle rampart over a distance of about 35 meters. A second quadrilateral tower was erected on this site, added to the northern face of the defensive wall, about 4 meters from the older tower. The tower’s plan had a trapezoidal shape with dimensions of 9.6 x 13.5 meters. Its lowest floor was occupied by a single chamber, topped with a slightly pointed barrel vault, supported by a central, massive pillar. A bent passage with a pointed arched entrance led into the room, partly in the thickness of the older curtain wall.

After expansion, the southern edge of the castle was marked by a wall 10.5 meters south of both towers. On the extension of the east wall of the older tower up to the south wall, a four-arch wall of the new east wing was erected, with arcades spanning from 3 to 3.5 meters. Together with the southern wall and the west wing, it closed the courtyard in the corner of which the well was placed. Its surface was paved with granite river pebbles.

Current state

The medieval castle has not survived to our times. Remnants of a residential tower are located in a preserved gatehouse, including the original loophole in the northern wall of the eastern bay. Similarly in early modern buildings you can find the lowest floor of the fourteenth-century tower and some parts of its upper floors. Its pointed entry arch has also been preserved. The early modern palace, despite the announcement of the restaurant, is since the war in a state of ruin. However, four fragments of the town walls on the eastern and western sides of the former perimeter have survived to this day. At the church of St. Lawrence, you can see a defensive tower converted into a free-standing belfry.

bibliography:

Gaworski M., Zamek i park w Strzelcach Opolskich, Opole 2004.

Leksykon zamków w Polsce, red. L.Kajzer, Warszawa 2003.

Przybyłok A., Mury miejskie na Górnym Śląsku w późnym średniowieczu, Łódź 2014.

Romanow J., Wyniki badań sondażowych w zespole zamkowo – pałacowym w Strzelcach Opolskich [w:] Badania archeologiczne na Górnym Śląsku i ziemiach pogranicznych w latach 2005-2006, Katowice 2007.

Siemko P., Zamki na Górnym Śląsku od ich powstania do końca wojny trzydziestoletniej, Katowice 2023.