History

The monastery of Poor Clares in Stary Sącz was founded by Kinga, a Hungarian princess from the Arpad dynasty, a duchess of Kraków and Sandomierz, daughter of the Hungarian king Bela IV and the wife of the Polish ruler Bolesław V the Chaste. In 1257, she received from her husband the castellany of Sącz, which later became a specific monastic dominion. According to tradition, Kinga and her sister Jolenta decided to enter the convent of St. Klara right after the death of Bolesław the Chaste in 1279, announcing this intention during the prince’s funeral. The formal foundation of the monastery in Sącz took place in 1280, and five years later Archbishop Jakub Świnka instituted an indulgence for visiting the monastery church and supporting the ongoing construction of a new temple with donations. It is also known that the church in Sącz was consecrated in 1332 by Bishop Jan Grot.

The first monastery buildings and the church were probably wooden. It is not certain when the construction of the stone temple began. Perhaps the work on it lasted from around 1285 to 1332, and thus partly while Kinga was still alive, and before prince Władysław Łokietek finally took power in Małopolska. It is possible, however, that the construction of the church began immediately before 1332, because earlier the works were not favored by obstacles made to the monastery by prince Leszek the Black, or the subsequent war for the succession in Małopolska, the imminent death of the founder in 1292 and the considered plans to move the convent to Nowy Sącz. The entire architectural detail used in it would also indicate the creation of the monastery church in the 14th century.

The nunnery received a very rich estates, consisting of the town of Sącz founded by Kinga (“Sandecz civitatem”) and 28 villages, of which seven (Podolin, Łęcko, Bieczyce, Ołbina, Podegrodzie, Moszczenica and Gołkowice) were old settlements known from earlier documents, and the rest new centers from the 13th century. The received goods belonged to the largest of all Polish Poor Clares monasteries, such as convents in Gniezno, Strzelno, Wrocław, Zawichost or Głogów.

Initially, the monastery was not fortified, as indicated by the escape of nuns from the Mongols in 1287 to the castle in the Pieniny Mountains. Probably already in the fifteenth century, the nunnery had its own perimeter of defensive walls, raised and adapted to gunpowder weapons at the turn of the 16th and 17th centuries on the initiative of Cardinal Jerzy Radziwiłł. During this period, major changes were caused by the reconstruction carried out after the fire of the claustrum at the end of the 16th century. Significant construction works were carried out in the years 1601 – 1605, when, at the request of Bishop Bernard Maciejowski, new buildings were built for the nunnery, and the fortifications were strengthened and rebuilt. The damages caused by the fire that took place in 1764 gave rise to subsequent early modern renovations and changes.

Architecture

The monastery of the Poor Clares was founded in the south-eastern part of the settlement in the fork formed by the Poprad and Dunajec rivers, in a place protected from the east by quite steep slopes of the hill, towering over the Poprad floodplain valley. On the west side of the nunnery, a road from Kraków to Hungary ran through the town on the north-south line, and behind it, at a considerable distance from the convent, a stream ran at the foot of a high hill. A small watercourse was also to flow through the area of the monastery itself, probably in the form of an artificially dug canal leading from the stream. In its vicinity, in the southern part of the complex, there was supposed to be at least one well.

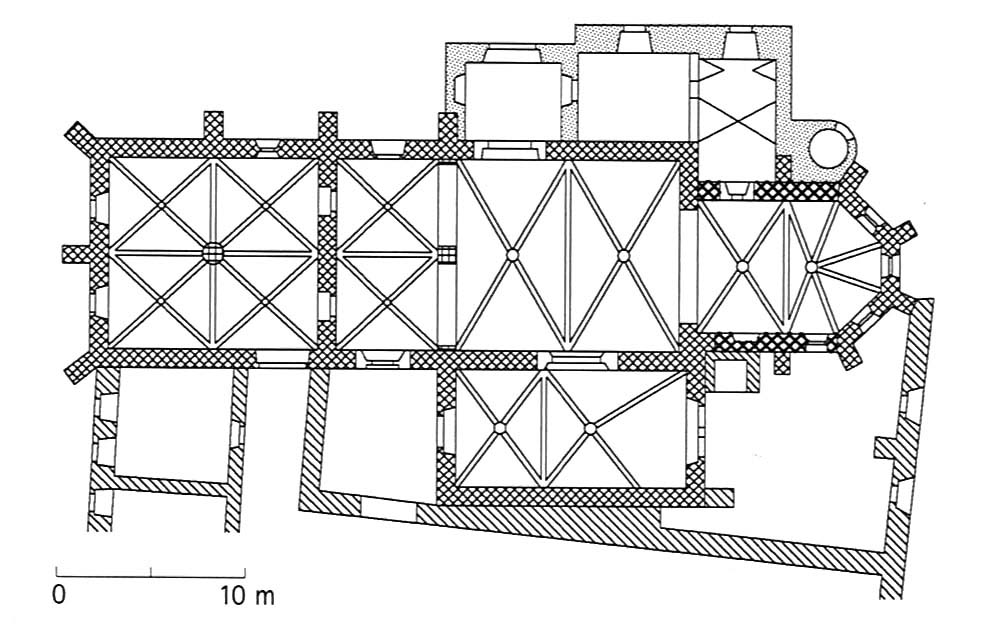

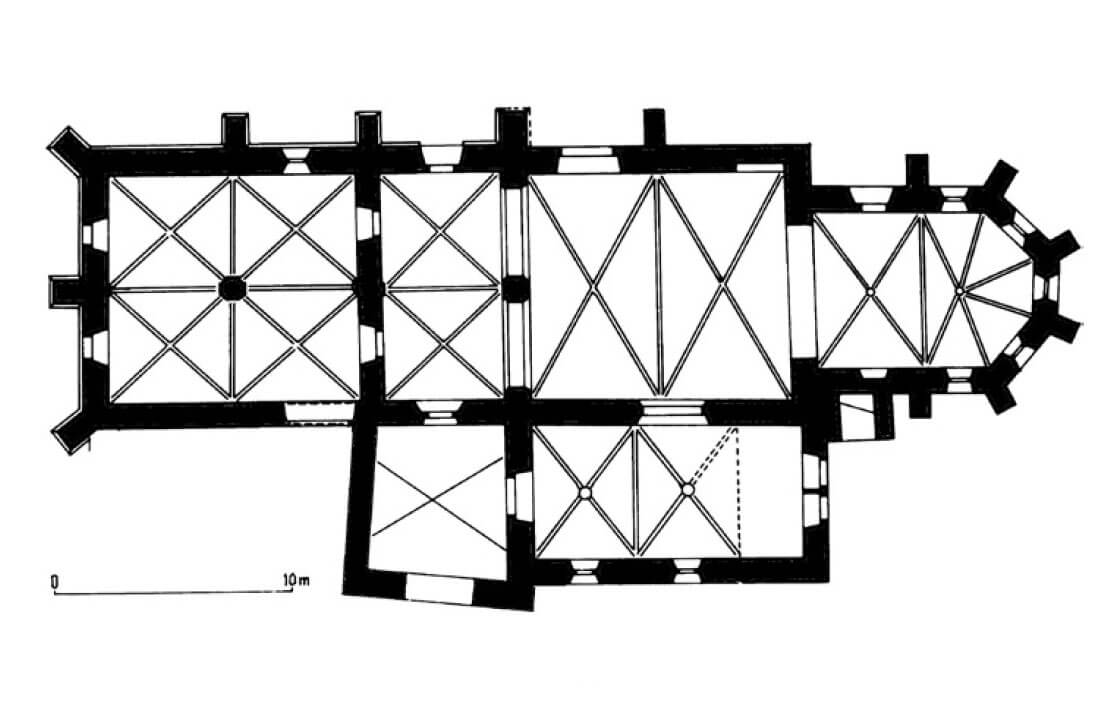

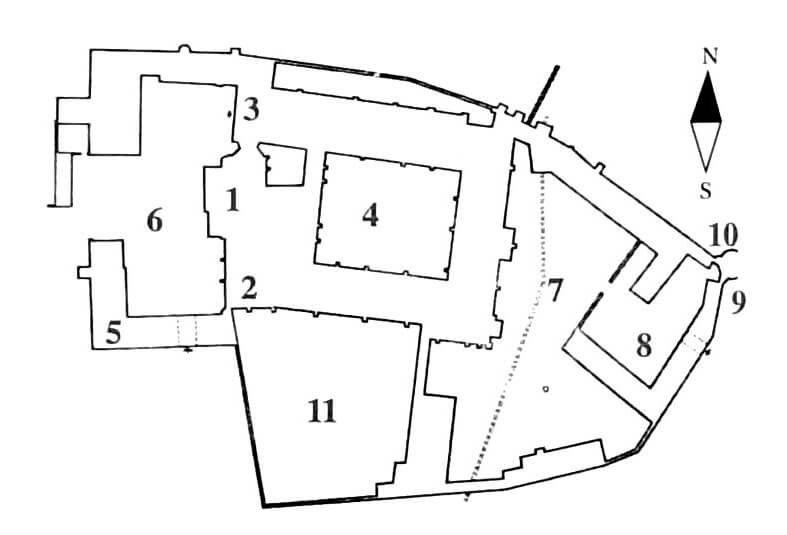

The main and oldest stone structure was the Gothic church of the Holy Trinity built of sandstones. It was erected as a temple consisting of a five-bay nave, in the eastern part housing a single-space aisle, and in the west part a chapter house, and a narrower chancel with a three-sided closing on the eastern side. The 14th-century chapel of St. Kinga, originally called St. Mary’s Chapel, was attached to the church from the south. It was probably erected with the worship of the founder in mind, as evidenced by its placement on the side of the monastery, but also ensuring communication with the nave, so that its interior was accessible to both sisters and lay people. Perhaps this was also related to a small room adjacent to the chapel from the west, the so-called the Confessional, which, according to the monastic tradition, was built on the site of Kinga’s cell.

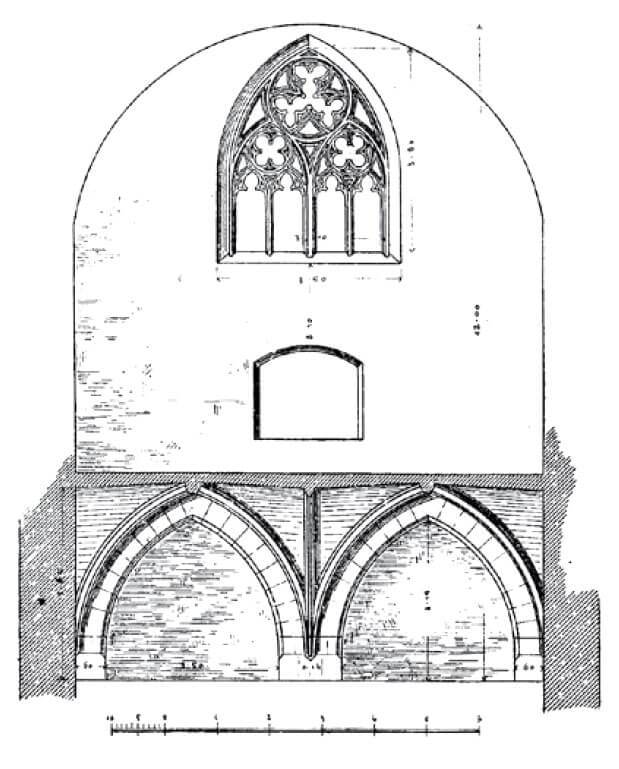

The façades of the chancel as well as the western and partly northern walls of the church nave were clasped with buttresses, between which high, pointed windows filled with traceries were pierced. The artist who created them was particularly fond of the two-light motif, crowned with a spherical triangle with pointed trefoils inscribed inside (perhaps modeled on those used in the Kraków cathedral).

The interior of the chancel of the church was covered with a cross-rib vault over the western, rectangular bay and a six-section vault over the eastern closure. The ribs received a pear-shaped profile in cross-section, and they were mounted on corbles in the form of inverted pyramids in the sides of which arcades with tracery finials were carved (again similar to consoles from the Kraków cathedral). The nave was also crowned with a cross-rib vault, although it was originally covered with a wooden ceiling. The central bay of the nave in the lower floor was opened to the eastern part of the nave with two wide, pointed arcades, based on a moulded four-sided pillar. Further on the western side, separated by a wall, there were two western bays of the lower floor, constituting the chapter house room. It was covered with a rib vault composed of four quadruple bays stretched around a central, octagonal pillar on a characteristic trapezoidal plinth. The ribs in this part of the church were much more massive than in the chancel with straight moulding formed by bevelled edges. At the top there was a gallery for nuns, open to the eastern part of the nave with a wide window filled with rich, sophisticated tracery. The St. Mary’s Chapel was also opened with a large opening onto the nave.

The entire architectural detail used in the western part of the church in the form of massive ribs with chamfered edges, merging into the walls and turning into miniature funnel-shaped corbels, as well as the heavy proportions of the pillars, clearly contrasted with the curves of the pear-shaped rib profiles and the elaborate tracery corbels in the chancel. Such a clear contrast between the various parts of the church was part of the specificity of Mendicant architecture. The massiveness of the pillars and ribs was largely due to their function, as they supported the gallery.

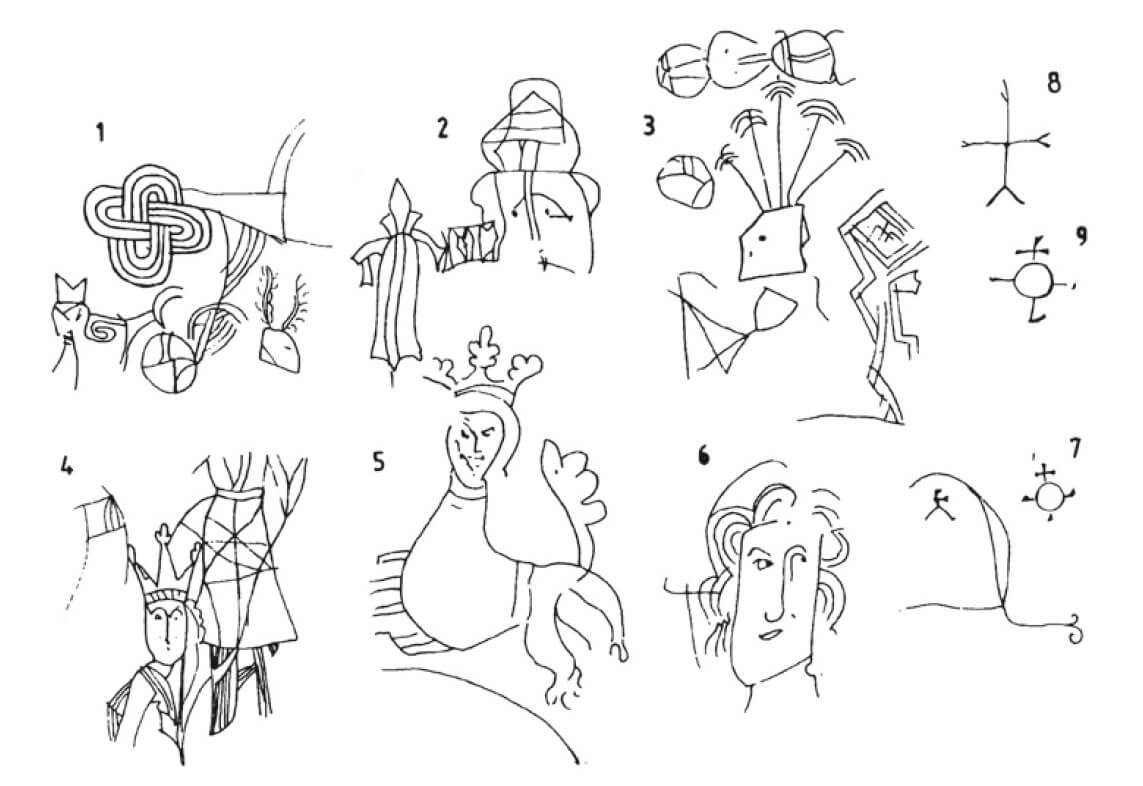

The walls of the chancel were covered inside with a set of engravings depicting ornamental, human and fantasy motifs (a chimera with a crowned female head), helmets with feathers and horns, as well as symbols and elements difficult to recognize. They were undoubtedly created in the Middle Ages, but their precise dating is hindered by their low artistic level, showing an unprofessional hand.

The buildings of the female claustrum (perhaps in the Middle Ages in part of the timber structure) were situated on the south side of the church, where they surrounded a four-sided garth. There had to be a refectory known from written sources, used not only for everyday meals, but also, due to the small space of the chapter house, to organize more important events or meetings. In the 16th century, it was supposed to be at the end of the west wing, which was connected with the church at the chapter house. On the south side, there were additional economic buildings, and the whole was surrounded by fortifications with the main gate located from the west, i.e. from the town side. The southern, corner section of the perimeter was defended later by a cylindrical, four-storey tower, extended entirely in front of the face of the wall, pierced with numerous key arrowslits and four-sided slits on the top floor.

Current state

The monastery of Poor Clares with a 14th-century church, is an important monument for the history of Małopolska, preserved in good condition despite later early modern transformations. Inside the church, elements of Gothic stonework, rich window tracery in the chancel and nave, corbels, vaults and three pointed portals have survived. The monastery rooms, consisting of four wings with cloisters around the garth, lost their original outer appearance after the Baroque rebuilding. The fortifications around the southern part of the nunnery are in good condition.

bibliography:

Architektura gotycka w Polsce, red. T. Mroczko, M. Arszyński, Warszawa 1995.

Krasnowolski B., Leksykon zabytków architektury Małopolski, Warszawa 2013.

Pajor P., Kilka uwag o okolicznościach budowy i formie architektonicznej kościoła klarysek w Starym Sączu, “Modus. Prace z Historii Sztuki XVIII”, Kraków 2018.

Przybyłowicz O.M., The architecture of the church and cloister of nuns of the Order of St. Clare in Stary Sącz in the light of written sources and literature of the subject, “Architectus”, 2(24), 2008.

Sypek A., Sypek R., Zamki i obiekty warowne ziemi krakowskiej, Warszawa 2004.