History

The building of the Starogard parish church began after the lands on the left bank of the Wierzyca River were seized by the Teutonic Order in 1305. They proceeded to fortify the settlement and erected a Gothic church of the Blessed Virgin Mary, on which the first stage of work lasted until about the mid-fourteenth century (in 1348 the Grand Master granted the town the privilege in which he endowed the local parson). The church was not built according to a uniform plan established from the beginning, but gradually gained its form through subsequent reconstructions and extensions. In the second half of the fourteenth century, the chancel was transformed, the nave was completed, and at the latest the chapels at the nave were added.

Throughout history, the church suffered from numerous disasters. The greatest damages hit in 1461 during the Thirteen Years’ War, in 1484 as a result of an accidental fire, and in 1655 during the Polish-Swedish war. The losses incurred at that time were not recorded in documents, but the brick vaults of the chancel and the nave were probably destroyed. During the 15th-century repairs, the gables of the chapels and the chancel were modified.

During the Reformation, the church was taken by Protestants who changed its call to St. Matthew. The building returned to Catholics in 1599, but the new invocation remained. Shortly before its return, the church underwent renovation, which was probably carried out without major structural changes. Further repairs took place around 1689, after the wars with Sweden. The last major construction modifications were introduced during the regothisation of the church at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, when, among other things, the western and northern porches were built. During World War II, the chancel walls and roof coverings were damaged, and the southern chapel was destroyed.

Architecture

The church was built in the north-west corner of the market square, in the vicinity of the town’s defensive walls, on a high riverside embankment. In the Middle Ages, it obtained the form of a four-bay basilica with central nave and two aisles, orientated towards the cardinal sides of the world, with a chancel, initially polygonal and then straightly ended on the eastern side. From the north, a sacristy was located at the chancel, and in the south-west corner, between the nave and the chancel, a small staircase in the form of a shallow projection. Another staircase, resembling a slender turret, was placed at the western facade of the nave. The chapel of St. Barbara from the north, the Chapel of the Transfiguration and the two-story southern porch were built at the aisles.

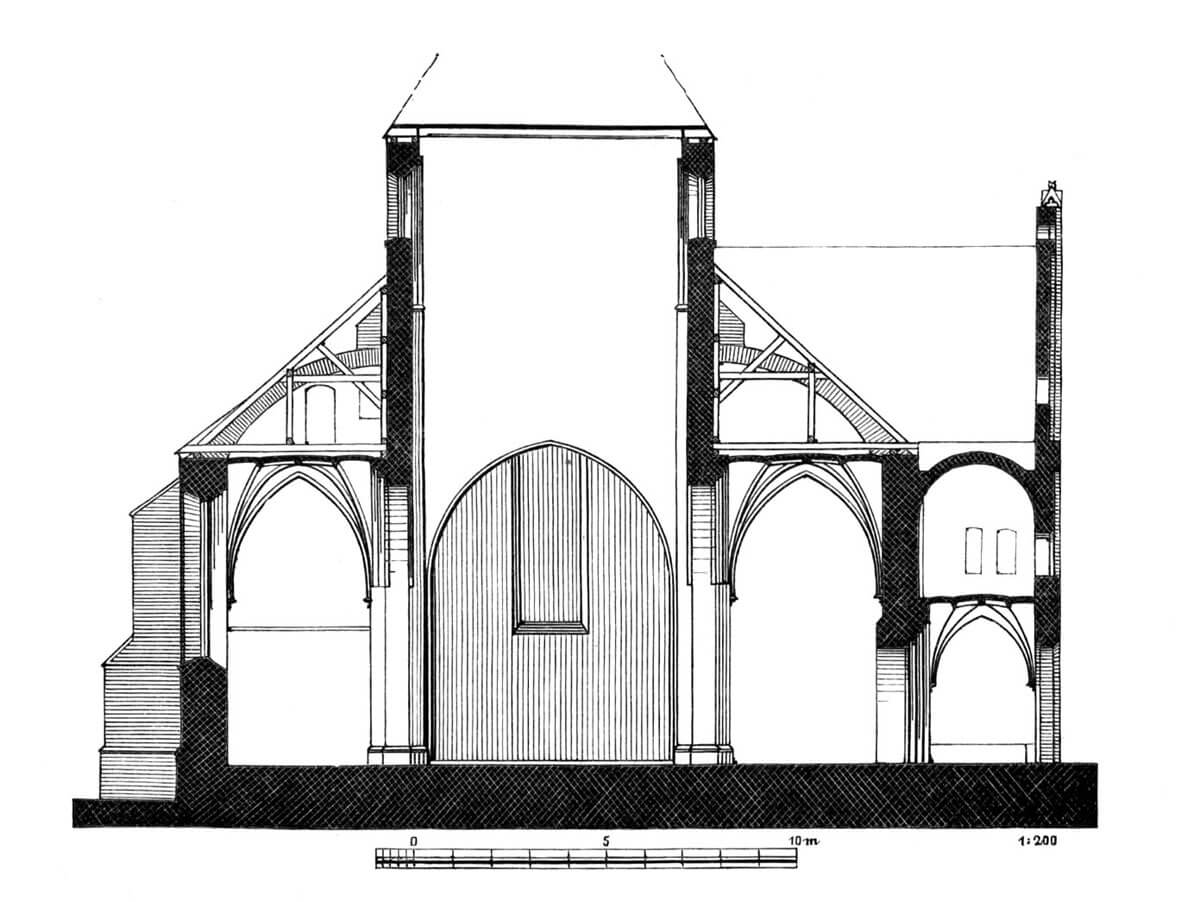

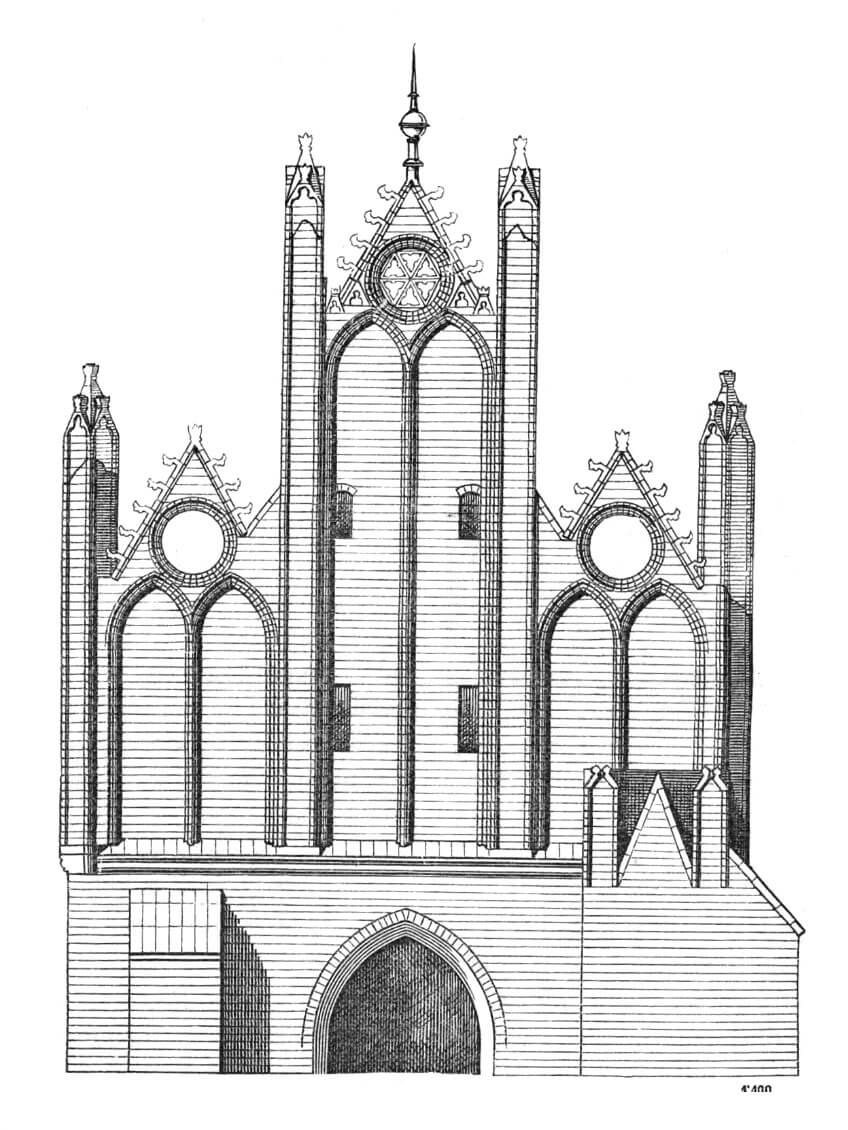

The brick walls of the church were placed on a stone plinth and fastened from the outside with buttresses. The structural system of the nave was complemented by flying buttresses, hidden under the roofs of the aisles, where they reinforced the higher walls of the central nave. The gable roofs of the nave and the chancel, as well as the mono-pitched roofs of the aisles, were based on Gothic gables and half gables. They were decorated with pairs of double blendes, circular openings, small gables with crockets and moulded pilaster strips passing into pinnacles, only the eastern gable of the chancel from the end of the 15th century was slightly more modest, stepped, with pinnacles.

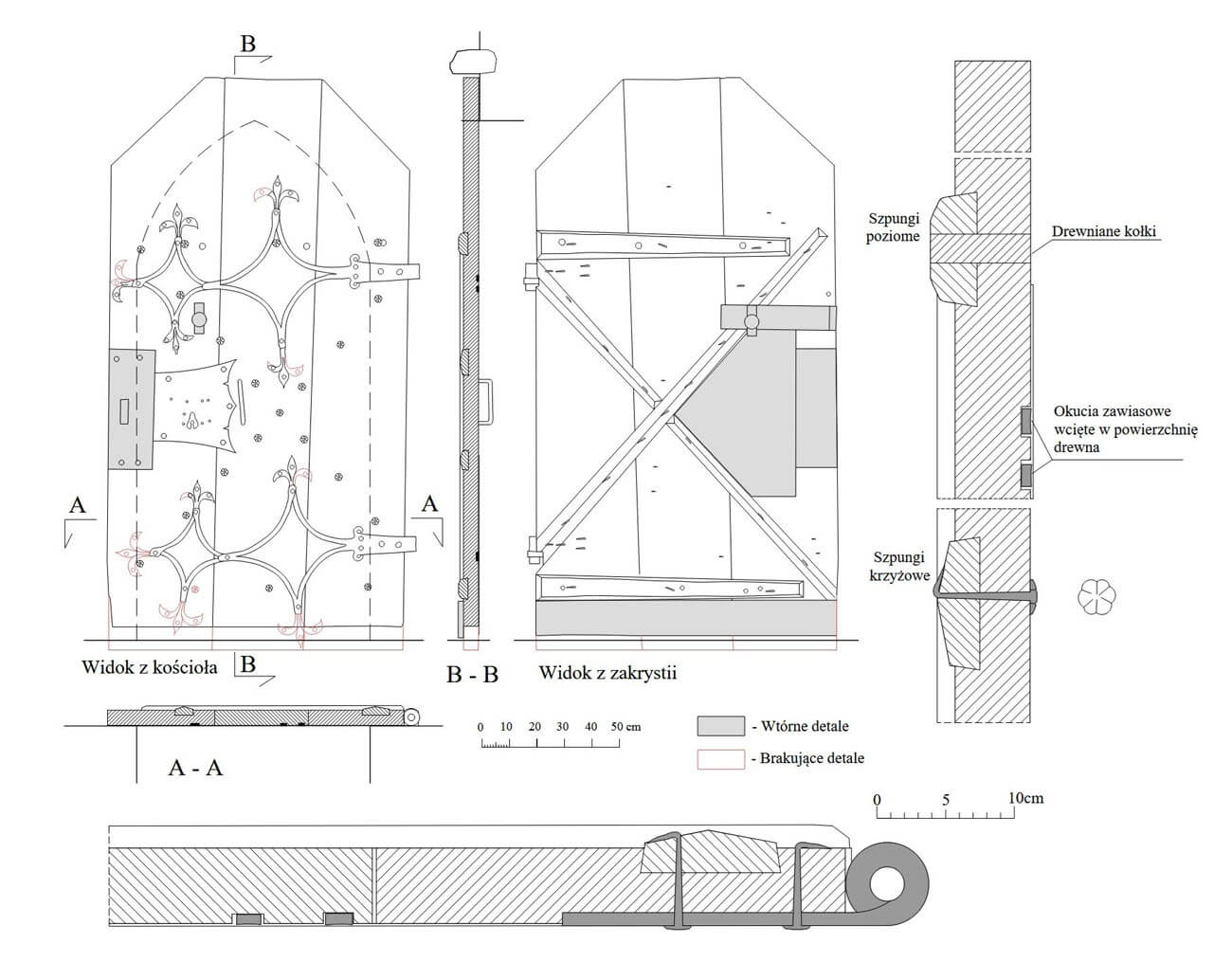

Entrances to the church led from three sides, except the eastern one. All of them were embedded in pointed, moulded portals, in which originally there must have been wooden doors, reinforced with iron fittings. An exceptionally solid door was installed in the sacristy, where the three wide boards were connected, as in other joinery, with horizontal pins running concurrently, but also with two slightly narrower diagonal pins in the form of the letter X. The doors leading into the church from the outside were protected against forced opening by a flat lintel stone. All windows had pointed heads, were splayed on both sides, and a cornice was led under them, in the presbytery part supplemented below with a frieze made of obliquely positioned bricks. The cornice was omitted only on the facades of the sacristy and chapels, while the façades of the chapels, unlike the other façades of the church, were decorated with blendes.

There may have been a vault in the central nave at a height of over 16 meters in the Middle Ages. The side aisles were covered with four-arm stellar vaults at a height of 7.6 meters, springing from the short shafts set on the pillars and on the opposite walls. The shafts were mounted alternately on corbels in the shape of decorative consoles or rollers. The division of the nave into aisles was ensured by three pairs of octagonal pillars without decorations, imposts or capitals, supporting pointed arcades. Characteristically, the two western buttresses were not placed on the axis of the pillars, although the function of the walls strengthening could also be performed by a massive staircase.

In the chancel, as in the nave, a vault was planned or installed in the Middle Ages, as evidenced by numerous buttresses. However, quite quickly it had to be replaced by a timber ceiling set at 11 meters, because any relics of the internal system of vault supporting were completely gone. The sacristy was originally probably covered with a two-bay cross vault. The ground floor of the southern porch was also vaulted with a stellar vault, and the southern chapel with a cross vault.

Current state

Today, the church has the original spatial layout, only slightly modified by an early modern west and north porch. A large part of the windows was transformed, and the gables and external facades were renovated during the regothisation at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. Inside, the vaults of the central nave and the chancel have not survived, while in the sacristy in place of the original vault, a barrel vault was installed, and in the southern chapel, the vault was given Renaissance forms. Inside, in addition to the vaults of the aisles, the wall painting from the mid-15th century, placed above the chancel arch, deserves attention. A portal from the 14th century has been preserved in the neo-Gothic west porch, you can also see the Gothic portal leading to the sacristy. In the latter, Gothic doors from the 15th century have survived, and another one has been preserved in the entrance to the choir.

bibliography:

Architektura gotycka w Polsce, red. M.Arszyński, T.Mroczko, Warszawa 1995.

Darecka K., Gotyckie drzwi na Żuławach i w ich bezpośrednim otoczeniu. Konstrukcja, okucia, kolorystyka, “Wiadomości Konserwatorskie”, nr 78/2024.

Die Bau- und Kunstdenkmäler der Provinz Westpreußen, der Kreis Pr. Stargard, red. J.Heise, Danzig 1885.

Grzyb A., Strzeliński K., Najstarsze kościoły Kociewia, Starogard Gdański 2008.

Szwoch R., Starogardzka fara św. Mateusza, Pelplin-Starogard Gdański 2000.