History

The origins of the Bernardine friary in Radom date back to the second half of the 15th century, when the order was brought to Poland by King Casimir IV Jagiellon, and to Radom town on the initiative of starost Dominik Kazanowski. The site for construction was designated in 1468, and the following year it was approved by the Bishop of Kraków. Initially, the church and monastery, built within one or two years, were made of wood. Because the friary was located outside the town walls, the friary took the form of a defensive building, surrounded by ramparts, allowing for shelter in the event of an enemy attack.

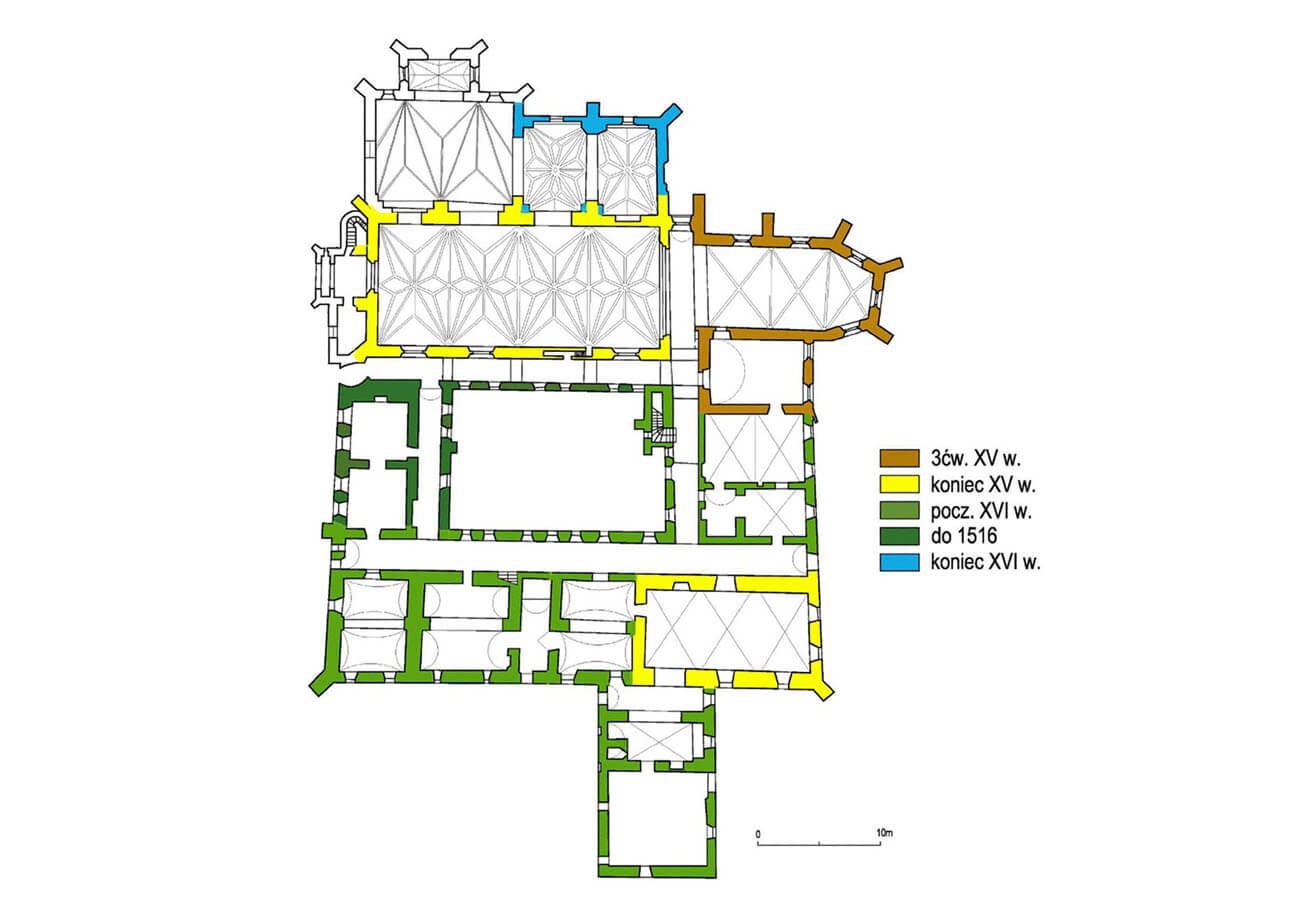

The brick church and monastery were built in several phases. The Bernardines themselves built a brickyard in which they fired Gothic bricks, slaked lime and performed themselves masonry works. First, in the third quarter of the 15th century, a chancel was built along with a sacristy, which was to serve as a treasury and library (since the beginning of the monastery’s existence, there was a monastic study there, for which a library was very necessary). Then the southern wing of the claustrum was built, and in the next stage the church nave, built at the end of the 15th century or at the beginning of the 16th century. At the latest, in the first quarter of the 16th century, the remaining claustrum wings were built, connected by a multi-story cloister with a low turret, typical of medieval Bernardine monasteries. It is possible that the construction of the friary was completed by 1516, because then the provincial chapter was held in the Radom under the leadership of Rafał from Proszowice.

In the 16th century, the Bernardine friary was surrounded by a defensive wall and earth ramparts due to frequent Tatar invasions. Then, in 1598, a late Gothic chapel of St. Anna was built on the north side, consecrated by the Bishop of Lviv, Jan Dymitr Solikowski. However, more serious early modern transformations took place only during the rule of the Guardian Szymon of Sokal at the beginning of the 17th century. Around 1602, the chancel was to be rebuilt, perhaps due to static problems. The remaining parts of the church, including the tower, were also renovated, and the functional layout of the rooms inside the enclosure was changed. In the 18th century, the interior of the church and monastery was baroqueized.

During the January Uprising of 1861-1864 the friary was a place of patriotic manifestations. Here also important decisions were made with the col. M. Langiewicz. This activity was met with tsarist repressions, which resulted in the exile of many monks to Russia. By the tsarist order friary was closed, and the buildings were taken over by the government, the army and the police. In the years 1911-1914 the restaurant and the extension of the church were designed by architect Stefan Szyller. On the west side, a “tower” with a staircase and two porches were added. In addition, the church was rebuilt and later St. Anna and St. Agnes chapels joined to the aisle. Bernardians recovered the church and friary in 1936. Recent major refurbishment works were carried out in 1998-2000.

Architecture

The friary was located outside the defensive walls of the medieval town, on the road leading from the Lublin Gate, in Jedlińskie Suburb area. At the end of the Middle Ages, the monastery complex included the church of St. Catherine of Alexandria together with the nave, chancel, sacristy and treasury, and three wings of the claustrum added to it, which surrounded a narrow garth. On the southern side of the monastery there was a utility wing with a kitchen building. In addition, the monks at the monastery had a garden and a spacious yard with economic buildings, with a barn and coach house, as well as a fish pond and a meadow. In the 16th century, the whole friary was to be surrounded by a defensive wall and earth embankments.

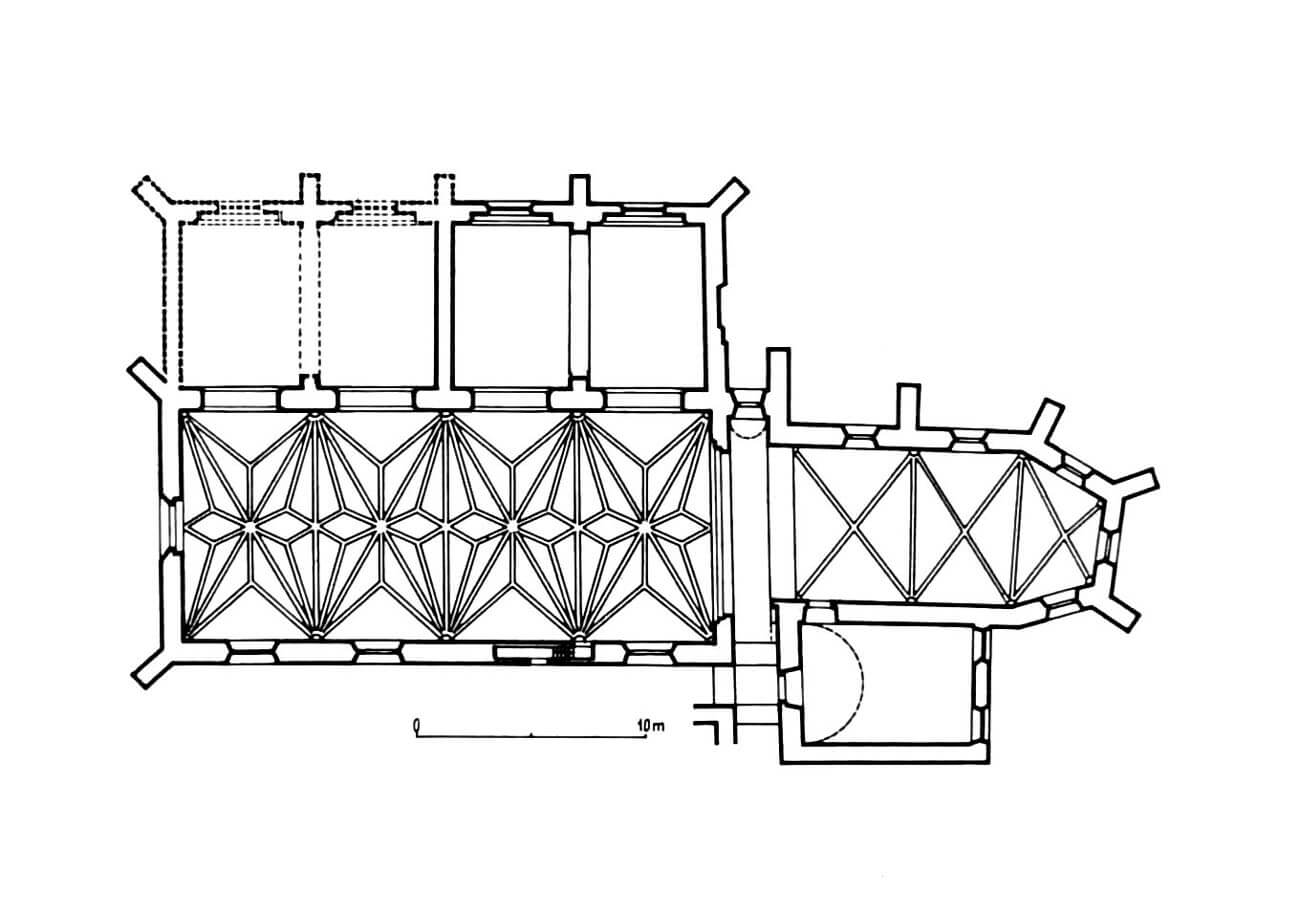

The friary church was created from a rectangular, aisleless nave and a short, lower and narrower chancel, ended on three sides in the east. The nave of the church was connected with the chancel by a residual, narrow transept, which probably originally housed a rood screen, separated on both sides by an ogival arcade. Originally, the main facade of the church was devoid of any extensions, and from the north, the nave was adjacent only to the two-bay chapel of St. Anna. The nave and chancel on each free side were reinforced with buttresses, between which there were pointed windows, a modest portal leading directly to the church, and a rosette above it. Around the nave, under the crowning cornice made of molded bricks, a frieze of diagonally placed bricks was placed. Above it, the western stepped-pinnacle gable was decorated with semicircular blendes. The interior of the nave was covered with a six-arm stellar vault with ribs springing from stone corbels, while the chancel was divided into three bays of a cross-rib vault.

The entire southern wing of the claustrum was originally a detached building with a basement, made of Gothic bricks. Its two corners on the eastern and western sides were reinforced with buttresses, covered with brick roofs, and the facades were pierced with pointed-arch windows. The wing was covered with a gable roof, framed by two different gables, decorated with plastered and black blendes. The eastern, oldest part of the wing on the ground floor housed the most important room from the point of view of monastic utility, where meals were eaten. It was a large refectory, also serving as a meeting place for the chapters. From the west, it was adjacent to the guardian’s apartment, while on the first floor there were cells of the monastic dormitory, which was extended towards the west at a later stage of construction. In the north side was a passage along the entire length of the building, which later served as a kind of arm of the cloister.

The eastern wing of the claustrum, built at the beginning of the 16th century, connecting the church with the southern wing, housed a library adjacent to the sacristy. The sacristy, built together with the church chancel, was also intended to serve as a treasury. It was covered with a barrel vault and illuminated with windows with stone frames. The western wing enclosed the entire complex in a quadrangle, with a inner garth in the center. Initially, the buildings of the western and eastern wings were probably single-story. Later, both sides of the claustrum were raised and covered with gable roofs. At the beginning of the 16th century, the entire complex was connected from the side of the church by a covered cloister with pointed arch passages in the buttresses. In the north-eastern corner of the courtyard, on reinforced walls, a small, rectangular tower was built, which was originally covered with a low hip roof.

At the beginning of the 16th century, a large utility facility was added near the refectory, located with its longer axis perpendicular to the southern wing of the monastery. There was a kitchen with a pyramidal chimney, next to which there were probably pantries, a smokehouse, a brewery, an oil mill and a wax melting plant, known from documents and chronicles. These rooms could have been connected to the southern wing by a long passage, built at the kitchen on the west side.

Current state

The Bernardine friary of Radom is one of the best-preserved medieval structures of this order in Poland, although it has not escaped early modern transformations. The chancel (probably only its apse) and the upper part of the tower were to be rebuilt. The porch, the turret with a staircase, the western extension and the neo-Gothic northern chapel dedicated to St. Agnes, including the porch, date back to the early 20th century. Chapel of St. Anna is today topped with a late Renaissance gable from the 17th century, most of the windows of the church and claustrum were modernized and enlarged, and the gables of the enclosure were also renewed.

Of the original architectural elements of the monastery, the vaults in the nave and chancel of the church along with their support system, a late Gothic portal in the western porch, 16th-century portals in the claustrum, and several windows in the eastern wing with late Gothic jambs have survived. A unique part of the monument is the economic building in the southern wing, housing a kitchen and a high chimney, the so-called “piekarnik”.

Among the movable furnishings, noteworthy are the stalls (without backrests and desks), dating back to the second half of the 15th century, currently located in the chapel of the Virgin Mary (former sacristy). An equally valuable element is the Crucifixion Group, placed in the main altar, made in the workshop of Veit Stoss, probably at the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries. Life-size figures made of linden wood are currently placed in the apse of the chancel.

bibliography:

Architektura gotycka w Polsce, red. M.Arszyński, T.Mroczko, Warszawa 1995.

Janicka A., Kościół i klasztor bernardynów w Radomiu od XV do XVIII wieku, “Acta Universitatis Lodziensis”, 85/2010.

Pierścionek B., Architektura gotyckich klasztorów franciszkanów obserwantów w Polsce XV-XVI wieku, Wrocław 2009.

Smirnowa L., Kilka uwag na temat architektury polskich klasztorów bernardyńskich [w:] Dziedzictwo architektoniczne. Rekonstrukcje i badania obiektów zabytkowych, red. E.Łużyniecka, Wrocław 2017.

Żabicki J., Leksykon zabytków architektury Mazowsza i Podlasia, Warszawa 2010.