History

Between 2nd century B.C. and 5th century A.D. the area of today’s Pruszcz Gdański, as well as its immediate surroundings, was one of the most significant settlements in Pomerania region. Pruszcz Gdański was at that time at lagoon lake, guaranteeing a direct connection to the sea. Thus, this area was one of the final points on the route connecting the amber coast of the Baltic with the areas of the Roman Empire. The location at the lake influenced both the development of trade contacts and the diet of the inhabitants with marine products. Apart from the hydrological factors, the development of settlements was affected by the favorable, lowland terrain, as well as the fertile soils of the Vistula’s Żuławy. The area of Pruszcz was an important center of provincial and long-distance trade.

Architecture

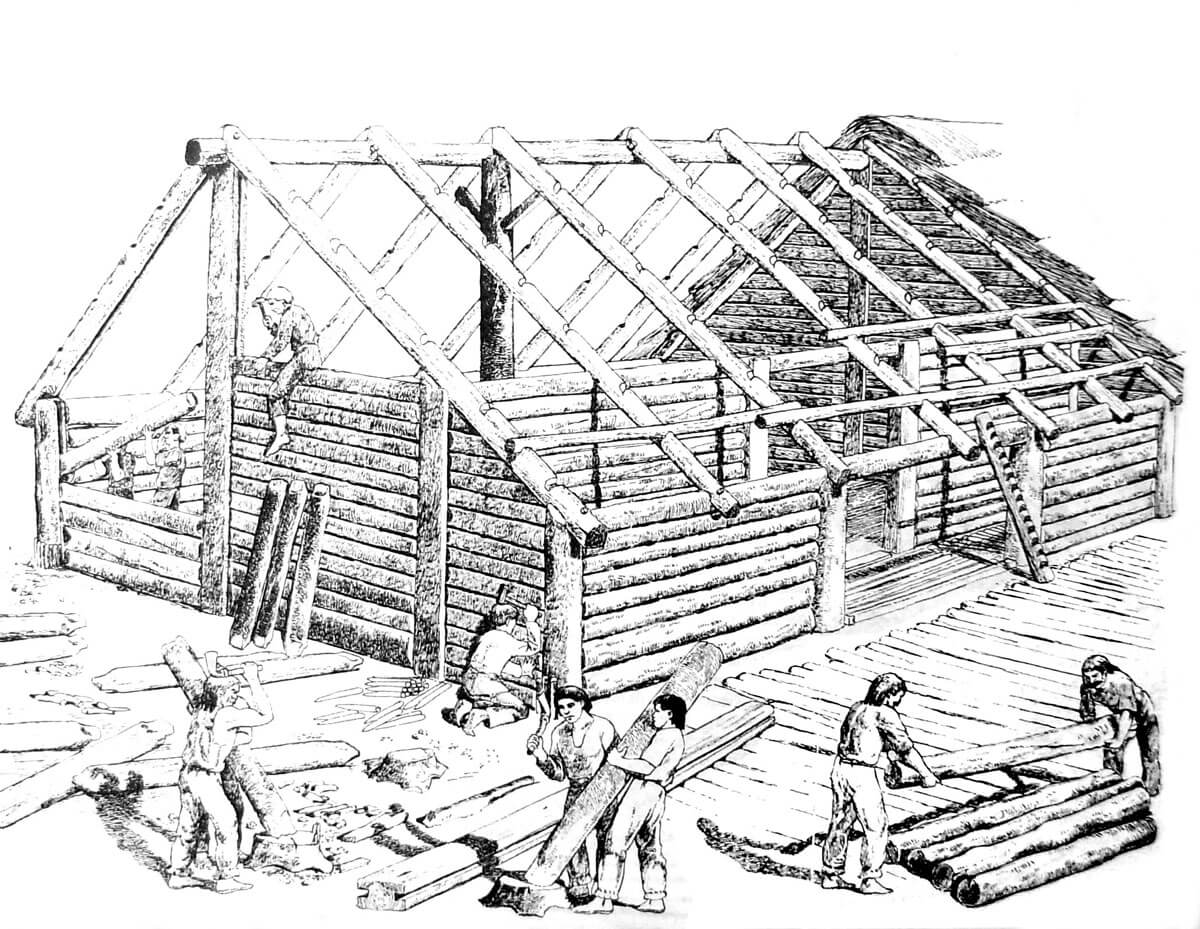

In the early Middle Ages, single-room wooden huts, the construction of which depended mainly on the local ground, were the basic residential houses in the northern Slavic area. Its groups in the form of settlements were fortified with palisades, earth ramparts, ditches and various kinds of obstacles. Fords, wetlands passages, port quays, bridges and customs chambers were also strengthened. Fences and enclosures for fields and homesteads were erected with smaller and larger farm buildings (sheds, utility pits, cellars, pigsties, later also barns, cowsheds, etc.), roads and dikes were lined with wood to facilitate transport and communication.

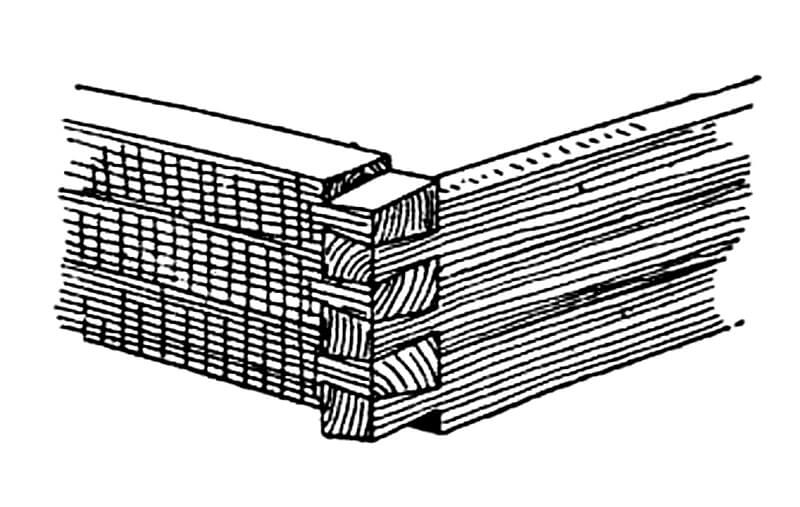

Half-dugouts and dugouts, i.e. houses sunk into the ground, usually had a square shape with rounded corners. Their depth was up to 1 meter in the case of half-dugouts and more when the dugout was built. A small sloping passage led into the interior, sometimes reinforced in the ground with steps, sometimes supplemented with a short ladder. The floor was hard earthen or covered with wooden planks. Timber walls were erected around, the height of which probably did not exceed 1 meter. It were built in a log structure, in which individual beams, suitably hewn at the ends and laid horizontally, were connected at the corners with the next beams, arranged at right angles. In the corners joints were used with or without the ends. The second method of building houses was the interlacing technique of thin branches, washed with clay on both sides. Pegs were hammered into the ground, wrapped with thinner twigs. Other pegs were used to support the arcades or covered the entrance. The roof was supported in half-dugouts on wooden poles placed in the middle of two opposite walls, or on poles forked at the top driven outside the outline of the walls. It was crowned with a ridge. Additional isolation of houses with roofs reaching the ground could be achieved by covering the whole hut with earth. The roof was covered with thatch made of straw or reed, mounted on beams protruding from the ridge.

The interiors of half-dugouts and dugouts, single-space, without divisions into smaller rooms, were small, often not exceeding 6-7 square meters. The hut was mainly used for sleeping and the day was mostly spent outside. For fear of fires, and perhaps also to reduce the heating of the interior, in summer, external fireplaces were used, placed directly on the ground. They were usually circular in shape, and were lined with erratic stones. Inside, the most important place of the huts were also circular stoves or fires, covered with stones or wood. They were located in the north-east corner, while the entrances were placed in the opposite, southern wall. The stoves were equipped with a dome made of clay, which was an additional source of warm. In the loess areas, the stove was buried in the corner of the hut in a specially left loess block. The stoves might have been just over a meter in diameter, but along with the ash pit and charcoal shoveled from the hearth, it took up about a quarter of the hut area. Near the stoves and hearths, in opposite corners, there were bedding made of straw, leather and fabrics, and perhaps also pillows stuffed with hay. In the rest of the household, supplies, farm equipment and tools could be stored. The entrances were secured with doors, probably braided, maybe additionally covered with leather or fabric. Could be closed with wooden pegs.

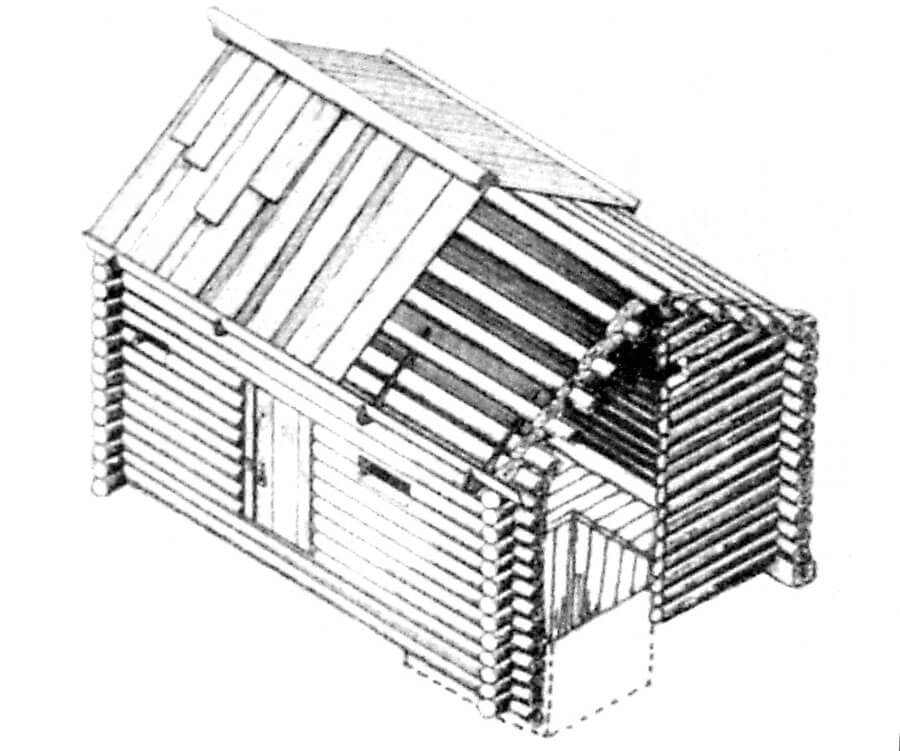

Above-ground huts were built mostly in the log and interlacing techniques. Most often they were larger than dugouts and half-dugouts, and could also consist of more than one room. It were erected without foundations, placing the first construction wreath on the ground. The gaps between the beams were closed with moss or clay, and the top beams, similar to the half-dugouts, had a roof constructed. An in-between-pillars structure of walls was also used, in which there was a plait covered with clay between the vertical beams, and in areas with less access to good building material, less covered with forests, a post-and-plank structure. In the latter, on the beam resting horizontally on the foundation, vertical elements were placed, and horizontal logs were inserted into grooves between them.

Entrances to the above-ground huts were usually placed in southern walls, and the doors were closed with an iron staple or a wooden peg. There were no basements inside, but the floors were often covered with planks or their surface was covered with clay. A hearth was set up near the wall or in the middle of the hut, most often of loose stones forming a circular or oval shape. Due to the fact that the huts were larger than the dugouts, some of them could be used to store the most valuable farm animals, or to organize craft workshops inside. The rest of the equipment was loose stools and hanging pegs. The tables were unknown, while the huts could have had millstones, bowls, benches, dishes for grinding groats and vessels for loosening flour and proving bread dough.

The construction of Slavic residential houses throughout the early Middle Ages was similar. The only differences were in strongholds and boroughs, where the houses grew smaller with time. In older settlements, houses could have been larger, placed loosely, at certain intervals from each other, but as the population grew, the buildings grew denser, and the houses had a smaller area and often adjoined each other, connected by common walls perpendicular to the course of the streets. Where there was a place, economic buildings were built next to the houses, in others you had to fit everything inside the huts. In order for the animals not to disturb the inhabitants, wooden “naras” were erected, i.e. primitive beds, sometimes storied, usually made of boards or poles. Pigs, sheep, dogs, cats, weasels, chickens and other domestic fowl could live under them. Huts with arcades were also erected, thus enlarging the living space. In the vestibules created in this way, supplies and equipment (tanning racks, sieves, roasters for drying grain, etc.) were stored. It was not until the 12th century that low upper floors were built to which steps or ladders led.

Current state

The Trading post in Pruszcz Gdański is a reconstruction of the settlement from the period of Roman influences, dating back to the period of splendor and the end of the Roman Empire from the 1st to the 4th century AD. It refers to the Amber Route that was functioning at that time. It consists of the leader’s hut, where are displayed exhibits of collections from the Gdańsk Archaeological Museum, the market hall where you can see a collection of reconstructed Roman era costumes, the ambermen hut reconstructing the craftsman’s workplace, and the smith’s hut, which is house reconstruction from the epoch of Roman influences. Also you can see a replica of a trade cart, stone circle reconstruction, animal farm, archery track and merchant stalls. The settlement is surrounded by a pallisade with four gate towers.

On the premises of the openair museum are organized cyclical shows and workshops, in which visitors can take part. You can find, among other things, the secrets of pottery burning, smithing, fabric dyeing, try your own in the forge, and taste fish from the historical reconstruction of the smokehouse and other dishes prepared with old techniques. In the summer time is available for visitors an archery track.

bibliography:

Godłowski K., Pierwotne siedziby Slowian, Kraków 2000.

Miśkiewicz M., Europa wczesnego średniowiecza V-XIII wiek, Warszawa 2008.

Miśkiewicz M., Życie codzienne mieszkańców ziem polskich we wczesnym średniowieczu, Warszawa 2010.

Website faktoria-pruszcz.pl.

Website wikipedia.org, Faktoria Handlowa w Pruszczu Gdańskim.