History

The town hall in Poznań was probably built at the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries during the reign of Wenceslaus II of Bohemia, although it can not be ruled out that it was created a little earlier in the second half of the thirteenth century. Already in 1280 there were three and in 1288 five councilors and jurors in the city. Town hall appeared for the first time in document in 1310. Next to the vogt ‘s house in the eastern frontage of the market square and the Poznań churches, it was a symbol and the pride of the city and, of course, the place where the municipal authorities were in office and the documents, privileges, seals and books (in which the authorities’ announcements and judgments were written) were storage.

Initially, the hereditary vogt was influencing the selection of the city council, and its composition was probably approved by the princes. After the abolition of the vogt office in the beginning of the 14th century, this role was taken over by the ruler, through the office of the starost, who influenced the shape of the municipal authorities. Since that time, the council had six councilors and two mayors, elected from a larger number of candidates by the starost. Apart from managing the city, the council was also a type of higher court instance (the mayor himself was able to adjudicate the sudden matters). The second important element of the authorities was the so called judical bench, mentioned already since 1288. Initially, its role was limited, but after the buyback of the vogt’s office by the city in the mid-fourteenth century, the vogt’s office was maintained as the chairman of the judical bench. This office required a lot of legal knowledge and enjoyed a great esteem. Most of the affairs were resolved by the vogt with jurors, but the lesser he could judge alone. The longest-serving vogts were Mikołaj Gocz (1448-1463) and Stanisław Czarnymaćko (1492-1517). The choice of jurors was made by the council among the elders of guilds.

In the fifteenth century, due to the increase of importance and wealth and the successful development of the city under the Jagiellon rule, the city council decided to make the first extension of the town hall. It was carried out at the end of the fifteenth century, and in the years 1504-1508 the interiors were rebuilt. Two late-Gothic portals with the date of 1508 provide evidence of the completion of some stage of work.

In 1536 a great fire broke out, which also consumed the town hall. In the years 1540-1542 the building, and in particular the tower was renovated. Still, its condition continued to threaten the catastrophe. In 1550 the city council signed a contract for a thorough reconstruction, combined with the expansion of the town hall, with the architect Jan Di Baptiste di Quadro from Lugano. The work lasted until 1560, and as a result, Di Quadro raised the building by one storey, expanded to the west, added an attic and a three-storey loggia. During this repair a new clock was ordered in locksmiths master Bartlomiej Wolf. Clock had also a “clown device, namely, goats”. The clock was installed in 1551.

In 1675 the lightning hit the tower, destroying it with a clock. Renovated in 1690, it was not long, as in 1725 it was struck by a hurricane. In the years 1781-1784, thanks to the efforts of the Good Order Commission, the town hall was thoroughly renovated. It was then given a shape that is basically presented to this day. The tower was crowned with a classicist helmet, on the east façade Franciszek Cielecki painted portraits of the kings of the Jagiellonian dynasty, and under the central turret was placed a cartouche with royal initials. Another major refurbishment was made between 1910 and 1913, when the renaissance polychromes were destroyed, replaced with black bossage, but the goats returned to the tower. During the fights for Poznań in 1945, the town hall suffered serious damages. The tower collapsed to a quadrangular Gothic base, and the interior was damaged by a bomb explosion. Renovation was conducted in 1945-1954, restoring the renaissance character of the façade.

Architecture

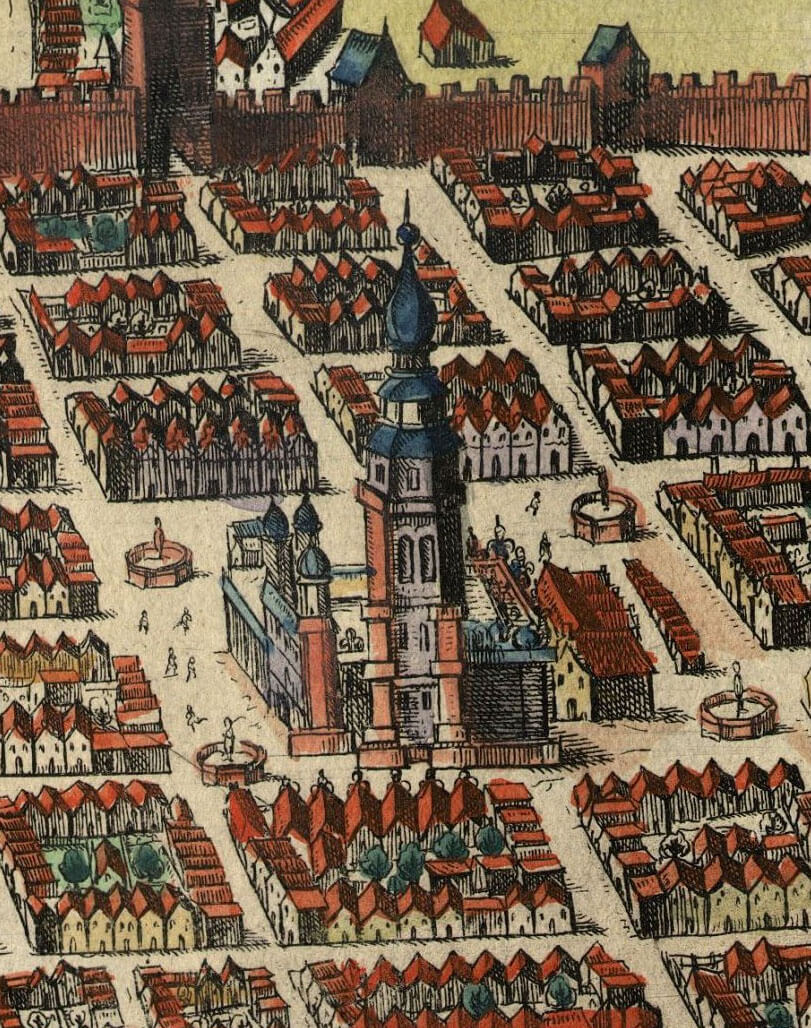

The place for the town hall was reserved at the junction of two main roads crossing the city: from the Wroniecka Gate from north to south and from the Great Gate from east to west. The town hall building was situated at the intersection of these axes, on the market square, in its highest place, as the surface of the medieval center of the city was not uniformly flat. The market was clearly lowered towards the east, which improved the outflow of water and sewage.

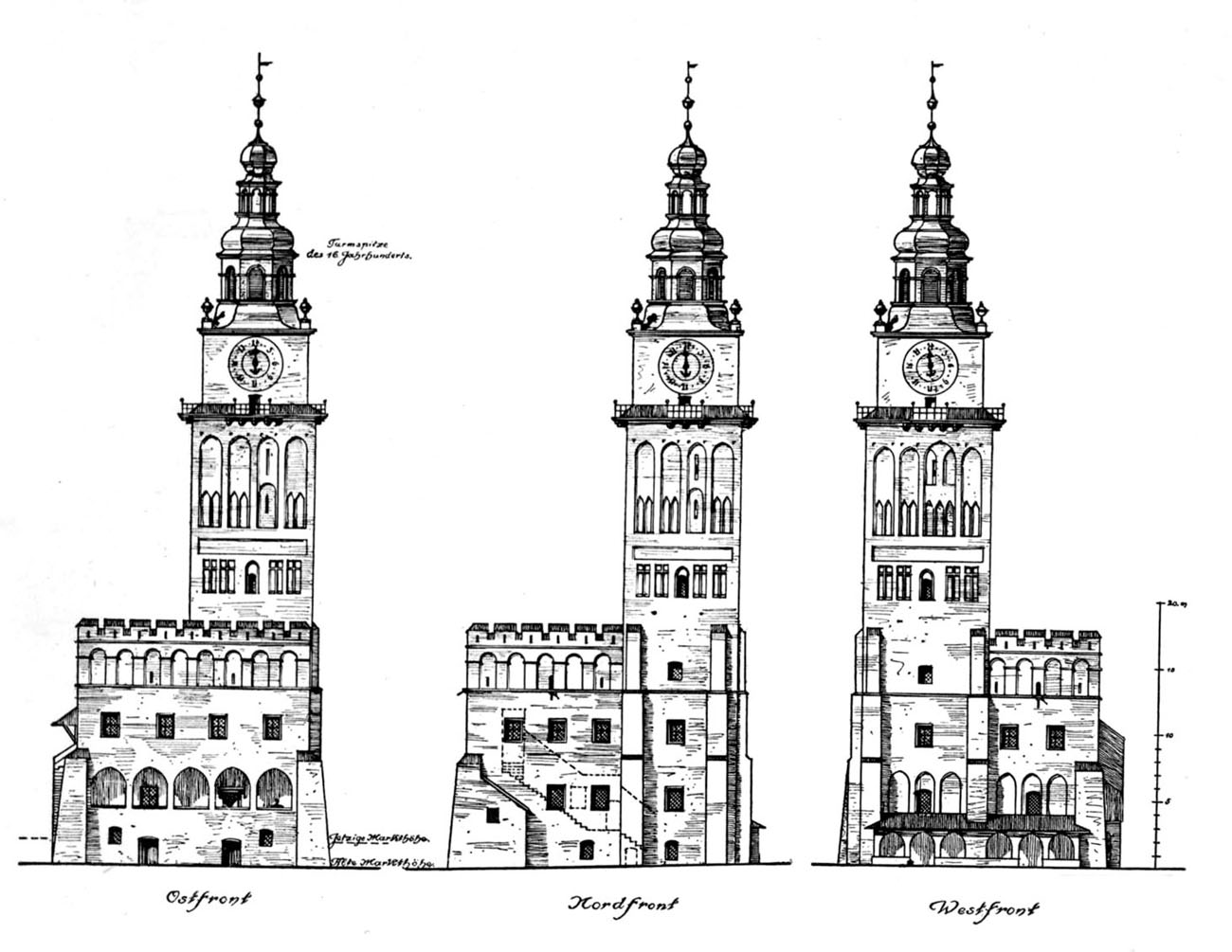

The original town hall building was erected on a plan similar to a square with dimensions of 17.8 x 15.9 meters. Its lower storey was about 3 meters deep below ground level, which meant that the main level (high ground floor) was about 2 meters above the market level. The walls of the ground floor were decorated with ogival moulded recesses (blendes), six on each façade. It house symmetrically spaced windows that could be plastered and covered with polychrome. The building was crowned with a high roof with gables from the north and south sides, and on the east covered with a decorative battlement with two polygonal turrets in the corners. This crowning probably functioned as a corona muralis – a symbol of the city’s idea and its legal values.

In the north-west corner was a square tower. It is uncertain whether it was built together with the building, or only at the end of the fifteenth century (in the act of city foundation, the vogt obtained the right to judge residents, which was symbolized by the tower – beffroi). It had at least three storeys and a cover in the form of a hip roof, perhaps with pinnacles in corners. At the end of the Middle Ages it was raised and strengthened with external buttresses.

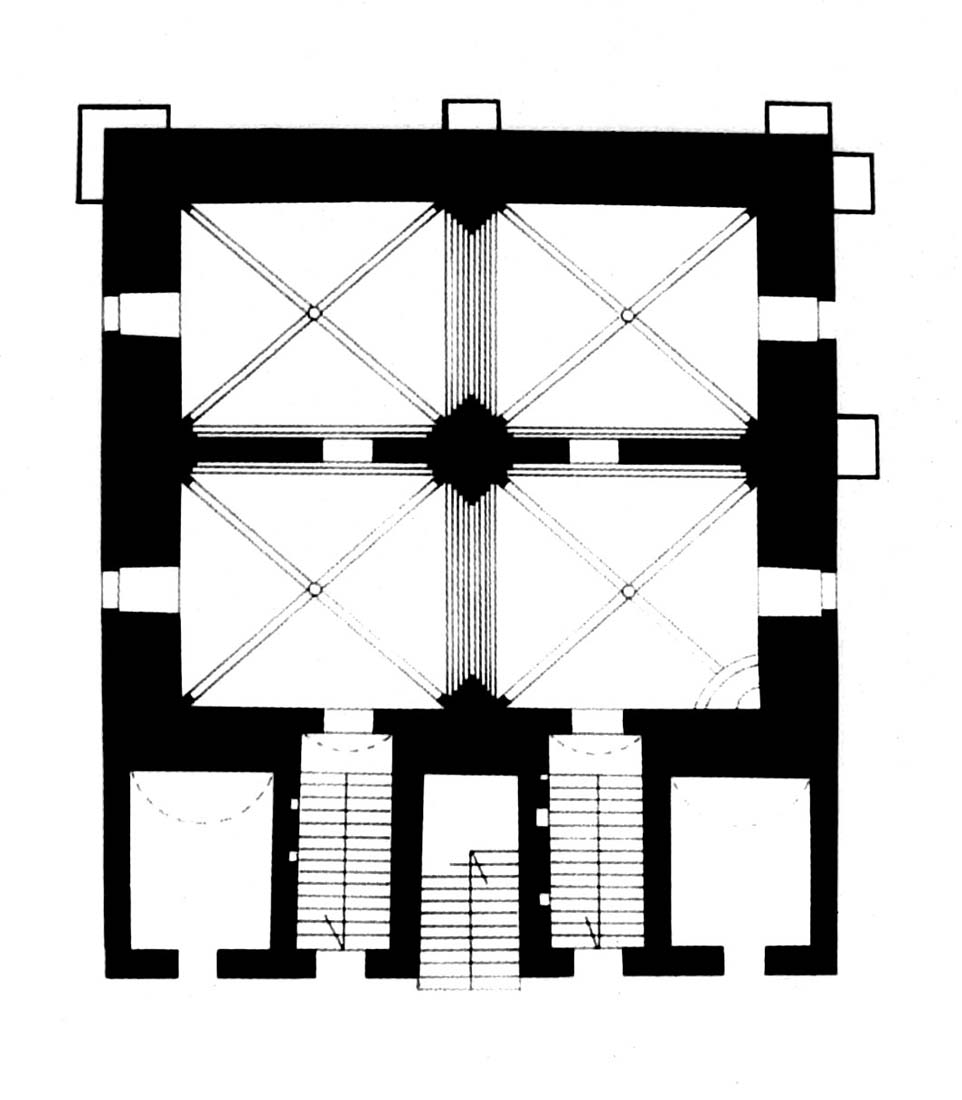

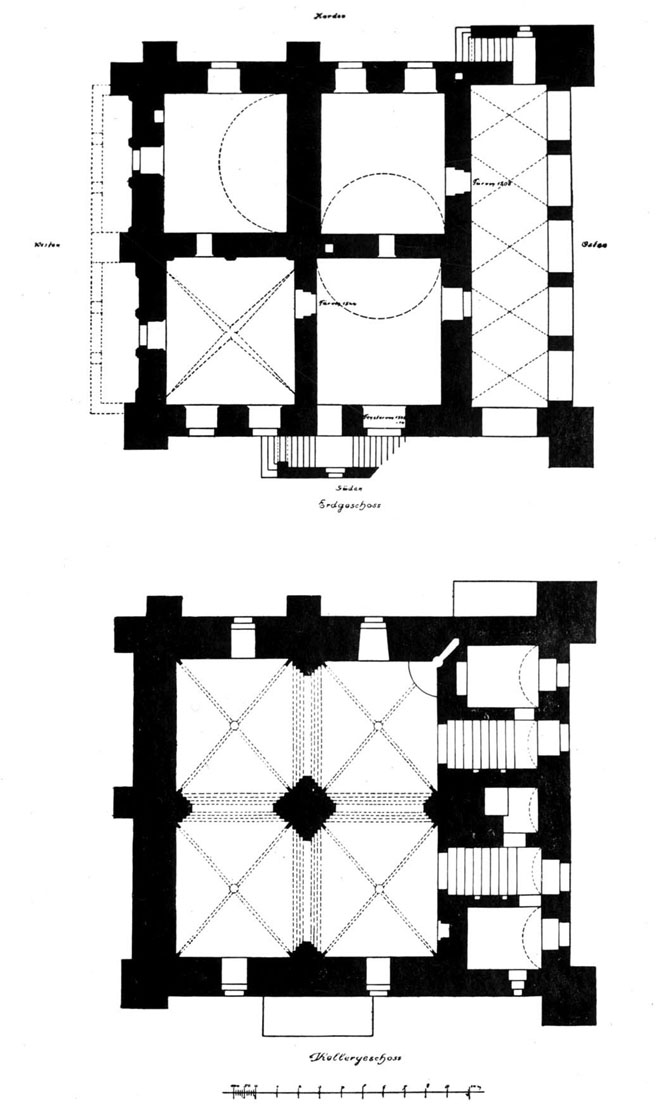

The building was preceded on the entire width of the façade with a stoop, advanced 5 meters forward. It had the form of a terrace in front of the entrance and was buried in the ground. The entrance to the lower floor of the town hall was just under the stoop, by two broad tunnel stairs. On their sides there were two small rooms, also available from the market level. The central axis was occupied by a wide staircase leading up to the top of the stoop. The basement was divided into two aisles with rib vaults flowing down to the floor. Both naves were lit with high windows in the north and south walls. The western wall up to the fifteenth century was devoid of windows, perhaps due to the functioning of a commercial building there. In the Middle Ages, the cellar was a storehouse for wines and other alcoholic beverages, for which the city council had a monopoly. In the north – east corner there was a fireplace, indicating that its role was also utilitarian, perhaps there was a torture chamber there.

The high grounf floor of the building was divided along the north-south axis into two bays, separated by a wall and covered with rib vaults. In the eastern part there was a large, longitudinal Judical Hall with three vault bays, while in the west there were two smaller rooms: a Council Hall in the south and a treasury in the north. The interiors had to be appropriately decorated. According to the practice, the floors were made of multi-colored tiles, the walls were decorated with paintings and expensive fabrics. Furniture was scarce and limited to the table, benches, a lectern for the writer, and chests for storing documents and books.

In the fifteenth century, the stoop was liquidated and a kind of late Gothic arcaded, vaulted porch was obtained by reinforcing and increasing stoop walls. After the demolition of the roofs and gables, the town hall was raised by one high floor and crowned with new high gables, covering the butterfly roofs. Probably the culmination of the walls was again decorated with battlement, and from the side of the façade probably still functioned corner polygonal turrets. As mentioned at the end of the fifteenth century, the tower was also raised, reinforced at the bottom with buttresses. Its next superstructure took place in the years 1527-1529.

The town hall building referred to the two-asiles northern constructions (Pomerania, Flanders), but it was much smaller and more compact, however it was distinguished by a tower that was rarely used on the Baltic Sea region. The distinction of the Poznań city hall was also the lack of rooms with commercial function, that occurred in the Pomeranian town halls. The compact shape of the Poznań city hall was also similar to the secular constructions from the areas of the Teutonic Order (town hall in Malbork, Pasłęk).

Current state

Currently, the facades of the town hall have a uniformly renaissance character. The only external evidence of the Gothic past of the building is the brick part of the tower. Inside the oldest part are Gothic cellars covered with rib vaults. Among the halls located on the ground floor only one of them has preserved the original vault. However, Great Hall on the first floor is one of the most beautiful renaissance interiors in Poland.

The town hall is now the seat of the Museum of the History of the City of Poznań. In individual halls, going up, are presented monuments associated with the stages of the history of the city, from the Middle Ages, to the present day. Every day at noon, you can hear a live bugle call, played from the town hall tower, during which the famous goats jumps. Museum opening times and ticket prices can be checked on the official website here.

bibliography:

Ratusz: Muzeum Historii Miasta Poznania, red. Warkoczewska M., Poznań 1993.

Skuratowicz J., Ratusz poznański, Poznań 2003.

Tomala J., Murowana architektura romańska i gotycka w Wielkopolsce, tom 3, architektura mieszczańska, Kalisz 2012.