History

The first church to the east of the village of Śródka near Poznań, dedicated to St. Michael the Archangel, functioned in the first half of the 12th century. In 1170, according to chronicler Jan Długosz, prince Mieszko III the Old and bishop Radwan established a hospital and a hospice for travelers and pilgrims there. In 1187, the church and the hospital were handed over by Mieszko the Old to the Knights Hospitaller, who helped travelers.

Around the middle of the thirteenth century (or at the earliest at the beginning of the thirteenth century), the Order began building a new church, one of the first in Poland, for the construction of which bricks were used. Knights Hospitaller changed its patron to St. John of Jerusalem, but for some time the old call was used in parallel. Until the end of the 15th century, the community consisted of brothers and priests, and the commanders acted on behalf of the brothers. Only the fourth one named Helman was recorded for the first time in 1338 as a commander, and it was he who used the invocation of the church of St. John the Baptist. The original invocation of St. Michael was used for the last time in a document of commander Nicholas Poppo from 1360. The local Hospitaller commandry had five brothers and a parish priest at that time, so it was not very numerous, although it enjoyed a strong position, as evidenced by the fact that it had a church in Kościan. There was also a parish at the church. Its origins could date back to the thirteenth century, but it was first confirmed in 1348, when the local parish, Sulisław, appeared for the first time in the document.

In the second half of the 15th century, the church and commandry declined. The debt relief and necessary repairs were carried out by commander Jan Pampowski in the 70s, and during the renovation, the church may have been given a Gothic character. Then, around 1512, under commander Stanisław Dłuski, a side chapel and a tower were added, and the wooden ceiling was replaced with a vault. Stanisław Dłuski was also probably the last commander who lived permanently in the court next to the church, where he died in 1520. The church farm of the commandry was then leased, among others, by commander Stanisław Mężyk in 1563.

The decline, destruction, depopulation and impoverishment of the commandry took place in the mid-seventeenth century during the wars with Sweden, and then during the Great Northern War and the plague that spread across Greater Poland region. The settlement and the commandry were able to rise from ruin to commander Michał Dąbrowski, nominated by the Grand Master in 1719. At that time, another renovation of the church was also carried out, during which in 1736 a Baroque chapel of the Holy Cross was added to the south.

In 1832, after the death of the last commander Andrzej Miaskowski, the Prussian government dissolved the commandry and the church was handed over to the diocese. In the interwar years, the church was in a very bad technical condition, and therefore its renovation began in 1928. The outer walls were plastered, with the exception of the west facade, which retained a medieval character, and the sacristy was connected with the chancel by an arcade. During World War II, the church was turned into a warehouse, which was damaged during the fighting in 1945. During the post-war reconstruction and renovation, efforts were made to restore some of the original Romanesque character of the building.

Architecture

The church was built on a small hill east of the Cybina River, at the junction of the roads from Poznań to Giecz and Śrem, near the pilgrimage route leading to the sanctuary with the relics of St. Wojciech in Gniezno. In the west, the border with the settlement, and later with the town of Śródka, was to be marked by a stone with an engraved Maltese cross and a large oak, behind which began the buildings of the commandry and a settlement with an inn and mills.

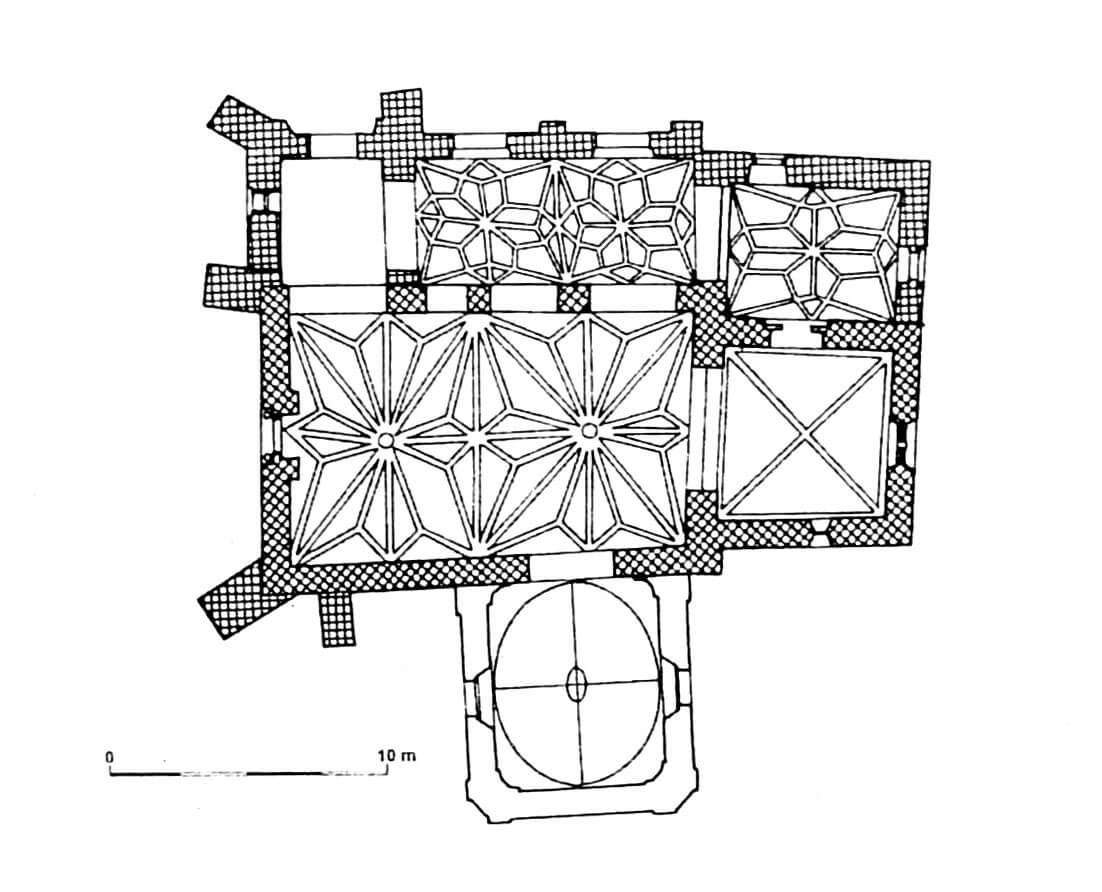

The late-Romanesque church was built of bricks in a monk bond. It was a relatively simple and small building, consisting of a rectangular nave with interior dimensions of 7.8 x 13.7 meters and a narrower chancel, also on a quadrilateral plan, 6 meters long on each side. The two parts were separated by a semicircular chancel arcade with a pattern without moulded corners.

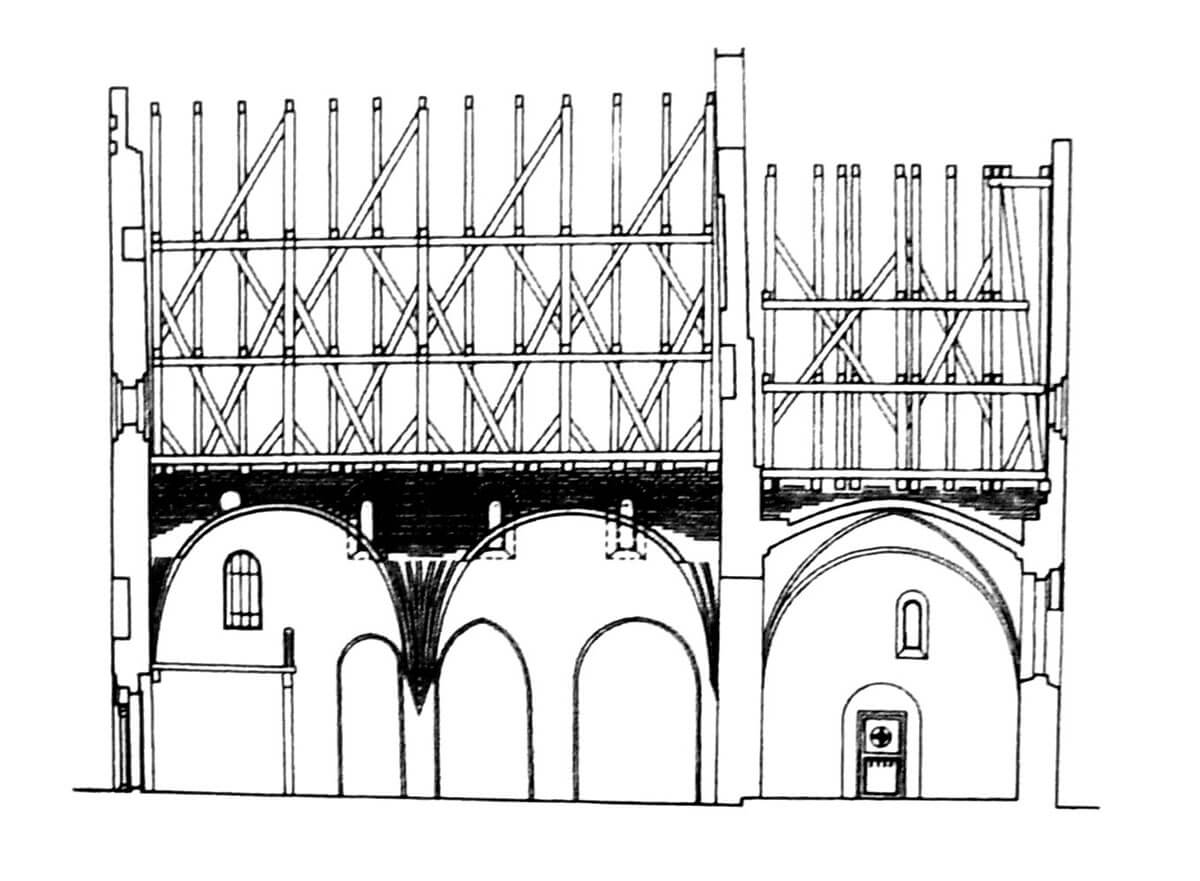

The nave walls were originally devoid of buttresses, so its interior was not covered with a vault, but only with a wooden ceiling. In the smooth side walls, window openings were highly pierced, semicircular, splayed on both sides, probably framed with ceramic jambs. The outermost windows at the west wall were round, and the stepped oculus in the west facade was similarly cylindrical. Its opening was filled with a rosette made of six radially arranged bricks. Below it there was a recess with a semicircular crown and on the sides two small windows with a shape similar to the recess. Over the oculus, a triangular gable was placed, raised in the Gothic period and equipped with four circular blendes with a rhombic pattern. There was also a place in the façade for the main entrance to the church, embedded in a stepped, semicircular portal. It was flanked by two columns of pink sandstone carrying a simple brick archivolt.

The presbytery, devoid of buttresses, may also initially have been covered with a wooden ceiling. The interior was illuminated by two windows in the side walls and another oculus in the eastern wall. In the thirteenth century, or during the renovation in the fifteenth century, the chancel was covered with a cross-rib vault of an original form, for which it is difficult to find close analogies. It received guiding and diagonal ribs with a shaft moulding, the latter suspended separately. In the devoid of corbels confluence, the ribs were narrowed and gradually embedded into the walls in the form of straight ends made of bricks set at the edge.

At the beginning of the 16th century, the church was enlarged by the late Gothic chapel of St. Stanislaus on the north side and a four-sided tower on the north-west side, in the corner between the nave and the new chapel. Perhaps during this period a small sacristy was also built on the northern side of the presbytery. The tower was supported by corner, massive buttresses, and its façades were pierced with semicircular windows and an entrance portal. The ground floor was covered with a wooden ceiling and opened onto the nave and the chapel. The second floor was the attic of the tower used to suspend bells.

The northern chapel was covered with a mono-pitched roof, while inside it was connected with the rest of the church by an arcaded, pointed-arch opening in the nave wall. The chapel’s vault had a stellar, four-arm form, without guiding and diagonal ribs, inscribed in the arrangement of an isosceles cross or diamond-shaped stars.

During the late Gothic expansion, a vault was also installed in the nave. Its gable and gable of the chancel were raised up, and the steepness of the gable roofs was raised. Due to the establishment of the vault, it became necessary to strengthen the Romanesque nave with buttresses. The nave was topped with a stellar, eight-pointed vault of a drawing with a guiding and diagonal rib. It was suspended without the use of corbels.

Current state

The medieval church has survived to this day, but it is obscured by a Baroque chapel from the south and a thoroughly rebuilt and enlarged sacristy in the north, and the brick façades of the nave and presbytery were significantly re-faced during subsequent construction and renovation works. The west façade, in which the monk bond remained intact, was the least affected. Most of the church’s windows have been transformed, although the remains of the original openings have been preserved in the attic above the late Gothic vaults (north and south Romanesque nave windows).

Inside, the nave and the chapel are covered today with a late Gothic stellar vault, and the 13th or 15th-century chancel by a cross vault. The changes to the interior resulted in the creation of two additional arcades between the nave and the northern chapel, an arcade openening to the sacristy, some of the walls were also covered with contemporary polychromes and a choir gallery was added to the western part of the nave. It is worth paying attention to the Romanesque west portal, decorated with two columns. One of them was turned upside down during renovation.

bibliography:

Krzyślak B., Kurzawa Z., Kościół św. Jana Jerozolimskiego Za Murami, Poznań 2011.

Maluśkiewicz P., Gotyckie kościoły w Wielkopolsce, Poznań 2008.

Świechowski Z., Architektura romańska w Polsce, Warszawa 2000.

Tomala J., Murowana architektura romańska i gotycka w Wielkopolsce, tom 1, architektura sakralna, Kalisz 2007.