History

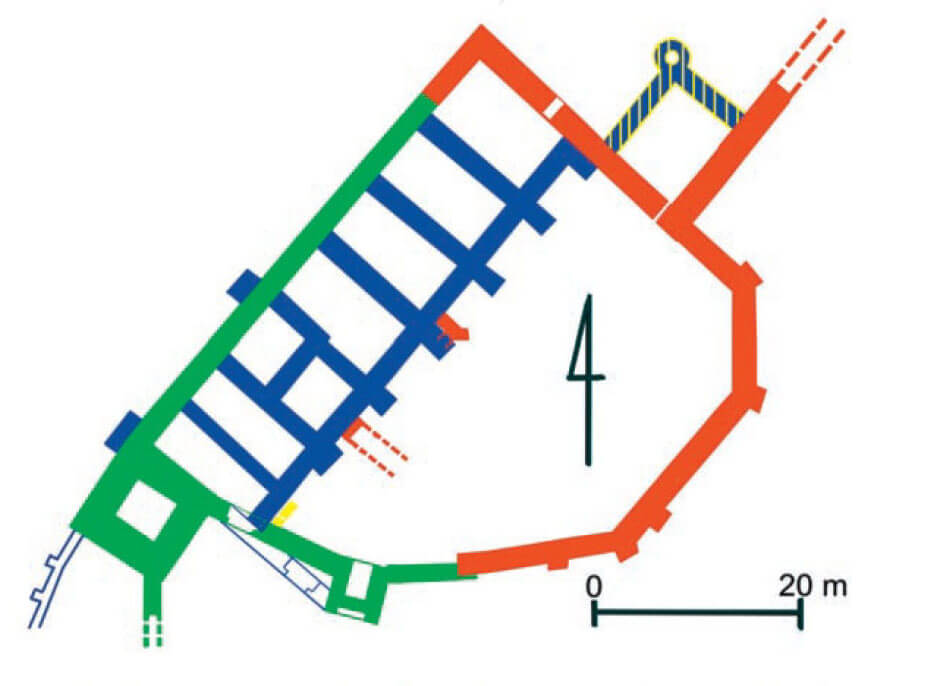

The construction of the brick castle in Poznań, together with the city walls, probably began in the times of prince and King Przemysł II, around 1280, although its beginnings in the form of wood and earth fortifications could have taken place even during the reign of Przemysł I, before 1250. In 1295 Przemysł II was crowned as king of Poland, unfortunately a year later he was murdered, and the extension of the castle unfinished. The interruption of construction in the first stage is witnessed by the change of the monk bond wall to flemish bond and different foundations. Works could be continued by the wielding Wielkopolska, Głogów-Żagań Piasts, and next, before 1337 king Kazimierz III the Great, who made at least 26 visits in Poznań. The castle residential building, originally probably timber, was added in the days of Kazimierz the Great or king Władysław Jagiełło.

Castle was the residence of successive kings: Wacław II, Władysław Łokietek and Kazimierz III the Great, who in 1341 took a wedding in Poznań with Hessian Adelaide. Two years later, in the castle was organized a wedding of the daughter of Kazimierz, Elisabeth with the Pomeranian prince Bogusław V. The military independence of the castle from the city was reflected in the events of 1383, during the internal war of the interregnum, when Grzymalit family, under the command of the general governor of Greater Poland, Domarat, defended in it, despite the fall of the city. After entering Poznań, the troops of Sędziwoj Świdwa, the castellan of Nakło, got through the window to the large wooden room under the castle, leaving an armed crew there. The defenders, however, were able to receive food through the gates leading into the field (“per portas castrenses”), so the fight after a 1.5 months long siege ended with the truce.

In the 15th century, the castle served as a royal residence during subsequent weddings, among others, Hedwigs, daughter of Kazimierz Jagiellończyk. This testifies to its residential and representative qualities. In 1493, King Jan Olbracht spent almost a year in Poznań, who accepted here the tribute of the Grand Master of the Teutonic Order Hans von Tieffen. In the periods when the monarchs were not in the city, the castle was the seat of the general starosts of Greater Poland, later the burgrave court and the municipal office. In the basement there was a prison for the low-born, and in the tower for the nobility (recorded in 1482). The starosts took care of the repairs of the castle. In 1434, Andrzej Ciołek from Żelechów undertook to repair the tower, and two years later king Władysław handed over the brickyard to the city, intended, inter alia, for the needs of the castle. In 1494, a part of the Greater Poland alcohol tax was allocated to its repairs. Despite this, in 1503 the nobility of Poznań complained about the poor condition of the castle and more renovations were needed, carried out in 1515 and 1533.

In 1536 the building burnt down, but almost immediately the staroste Andrzej Górka began renovation works, giving the castle a renaissance character. Renovation was continued by another starost Janusz Kościelecki before 1564, and finally it was completed before 1628. Again, it was seriously damaged in 1657 and in 1704 when it was occupied by the Swedes, it defended the access of the Muscovites and Saxons. The destruction caused him to lose his meaning. In 1783, Kazimierz Raczyński transformed the castle into a court building containing an appellate court and then an archive. After the destructions of World War II, the building of Raczyński was rebuilt.

Architecture

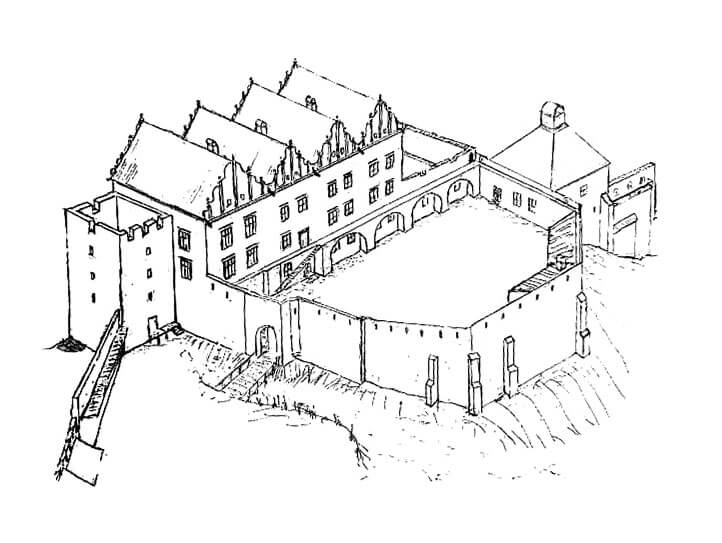

The castle was built in the line of the city defensive walls of Poznań, in its western part. It occupied a hill later called Przemysł Hill, located on the edge of the Warta valley terrace, towering over 15 meters above the level of the market square and even more above the Bogdanka valley located to the north and south of it. In the Middle Ages, there was a free square between the castle and the city buildings, which was to facilitate the defense of the castle. Leaving free space near the castle was additionally justified by the sloping terrain, which made building difficult. This small bailey, about 30 meters long, was separated from the castle by a not very wide moat, over which a wooden bridge was placed.

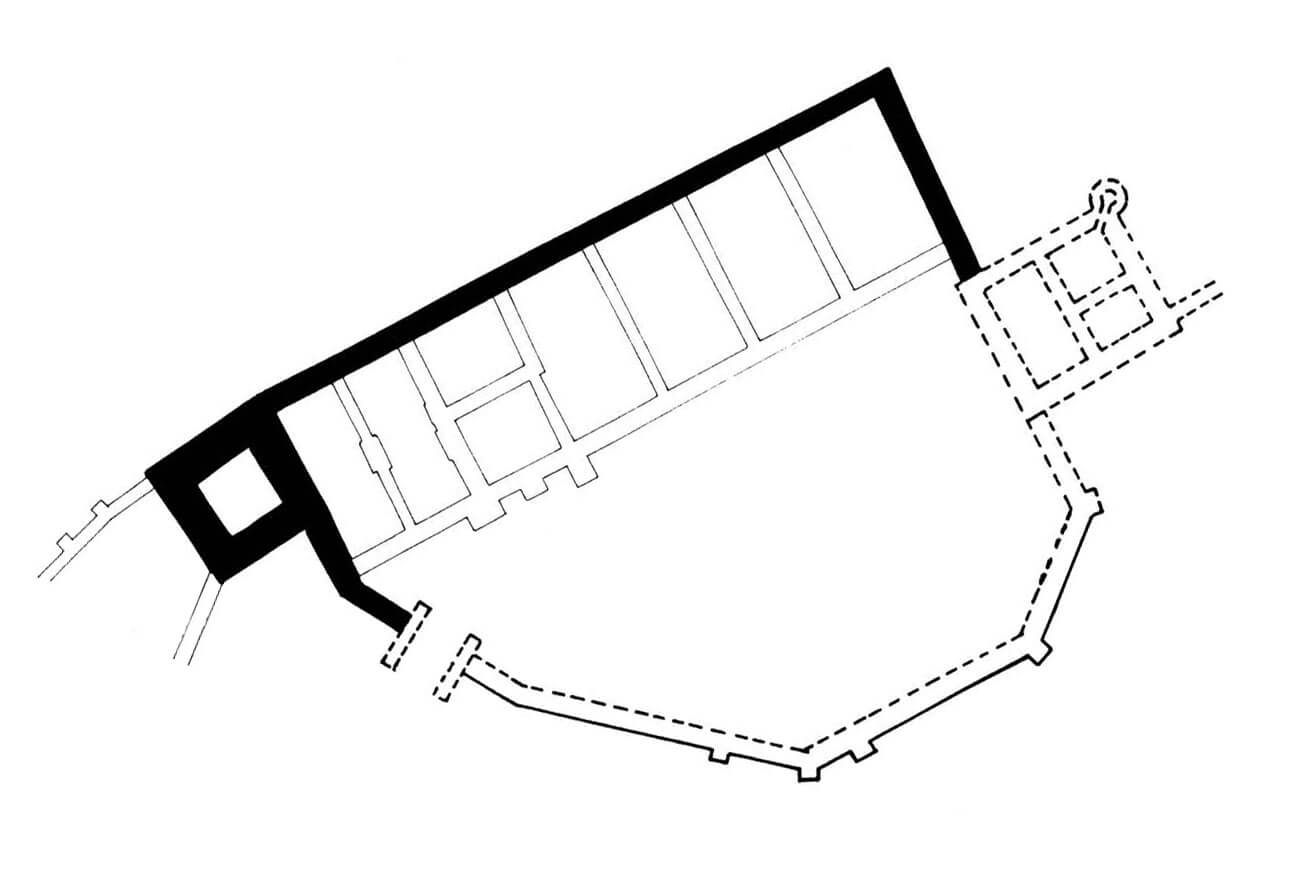

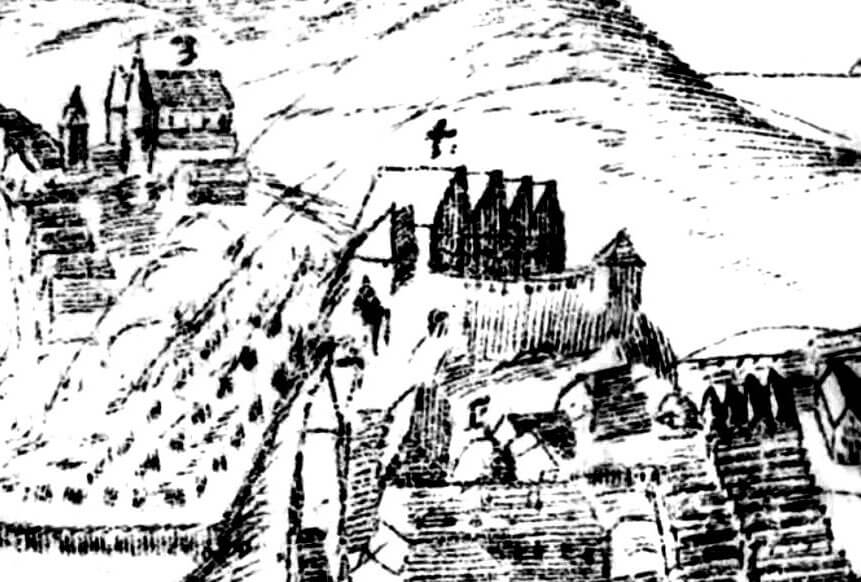

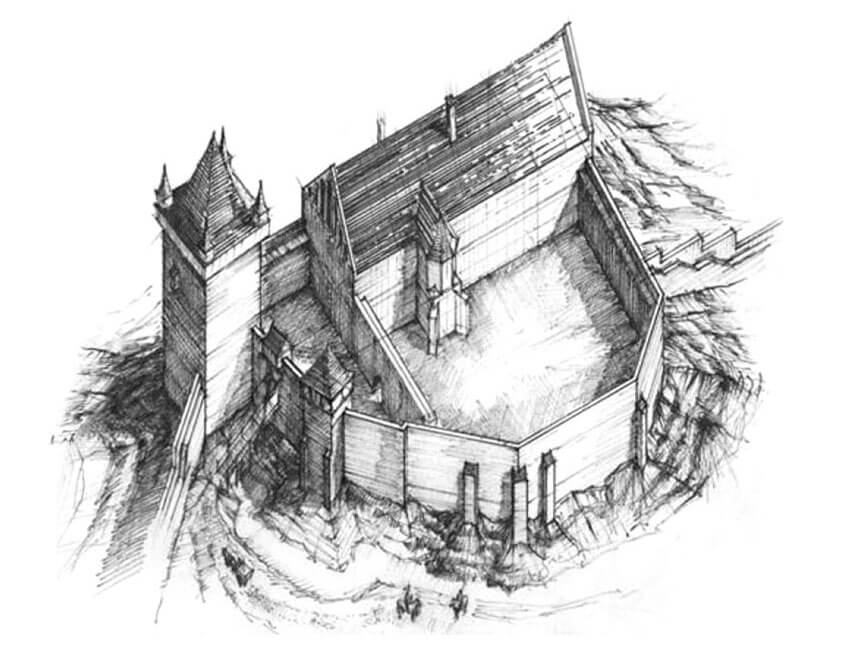

The defensive wall of the Poznań castle was built in two phases, differing in masonry techniques (the Flemish bond replaced the older monk bond). It surrounded the culmination of the hill on all sides, including from the city side. From the west and north it was closed by straight sections bent at right angles, while from the city side it created a curvilinear outline adapted to the shape of the hill. The whole structure had a horseshoe shape. The height of the walls in the 16th century was 6-7 meters, but it may have been slightly higher originally.

The western part of the castle was occupied by a large quadrangular tower, protruding in front of the castle wall in such a way that the city wall running out of its corner was set diagonally to its sides. The tower was built of bricks in the monk bond, on a plan close to a square with dimensions of 11 x 11.5 meters and walls 3 – 3.5 meters thick. In the lowest storey it had a chamber with an area of slightly over 29 m². The tower could initially have had a residential function, as it was quite large, but after the construction of the adjacent building it probably became a bergfried (a tower of final defense, not intended for permanent residence). In addition, it flanked the castle gate leading to the semicircular courtyard.

The only entrance to the castle was from the south, from the city area, defended by a quadrangular main tower. This was the only possible location, because the hill was protected from all other sides by a strong slope of the terrain. Right next to the entrance was a quadrangular turret measuring (together with the thickness of the perimeter wall) 4.6 x 4.9 meters, with an internal chamber measuring 1.3 x 1.9 meters, perhaps supported from the south by two perpendicular buttresses. Although the presence of a small turret was not typical, the entire Poznań castle at the beginning of the 14th century resembled the castles of the Czech Přemyslids, on which it could have been modeled, with the main tower incorporated into the perimeter of the defensive walls close to the gate.

At the turn of the 14th and 15th centuries, the northern curtain was extended by just over 9 meters, which gave it a total length of about 60 meters. In the times of Kazimierz the Great or, more likely, Władysław Jagiełło, the main castle house was built at this longest, straight section of walls. Its dimensions were probably slightly smaller than the building that was built there after the 16th-century reconstruction (approx. 17.5 x 63 meters). It was covered with one elongated gable roof and may have had a buttressed projection protruding towards the courtyard, possibly housing a staircase and a chapel. The interior of the house probably had a single-line layout of rooms. From the 16th century, it was divided into seven rooms placed in a row, of which the three outermost from the north did not have a basement, and the third from the south was exceptionally divided into two. During the reconstruction after the fire of 1536, the shape of the roof was changed. The building was covered with a set of four roofs arranged transversely to the longitudinal axis.

In the north-eastern part of the castle, probably at the beginning of the 16th century, a quadrangular house was built, once mistakenly identified with a 13th-century keep. It was situated in the external corner between the city and castle walls. This building, measuring 12.7 x 14.6 meters, housed a well in the corner in a small annex with a diameter of 1.8 meters. It probably served an economic function, because it is known that in the second half of the 16th century a new kitchen was located there. The castle certainly also had other wooden and half-timbered economic buildings, including an older kitchen attached to the eastern wall from the side of the courtyard.

Current state

The remains of the former castle include fragments of the perimeter wall, foundations from the 13th and 14th centuries, relics of the walls of the residential house rebuilt in the 16th century, partially incorporated into Raczyński’s later building, as well as the remains of the main tower, which survived to a height of about 5 meters, but due to the significant elevation of the ground level over the centuries were sunk into the ground. Since 2016, these elements have been covered with a new structure, the appearance of which has little in common with the historical castle, and in addition, it is made of modern and poor quality materials. The tower is definitely too high, the building has Renaissance features, but it was topped with pseudo-Gothic gables. Moreover, the construction of an ahistorical, pretentious and kitschy structure, a bizarre imitation of a medieval tower, had a negative impact on the landscape of Poznań and ruined the chances of better understanding the construction history of the real castle, due to the concreting of some of the medieval relics.

bibliography:

Leksykon zamków w Polsce, red. L.Kajzer, Warszawa 2003.

Olszacki T., Rezydencje Andegawenów po obu stronach Karpat. Wstęp do badań [in:] Zamki w Karpatach, red. J.Gancarski, Krosno 2014.

Olszacki T., Średniowieczny zamek królewski w Poznaniu: perspektywy badań i możliwości interpretacji, „Wielkopolskie Sprawozdania Archeologiczne”, t. 13. Poznań 2012.

Olszacki T., Różański A., Badania terenowe zamków z obszaru Wielkopolski i Polski Centralnej w XXI wieku [in:] Gemma Gemmarum, red. Różański A., Poznań 2017.

Pietrzak J., Zamki i dwory obronne w dobrach państwowych prowincji wielkopolskiej, Łódź 2003.

Ratajczyk T., Kaplica czy klatka schodowa? Relikty ryzalitu średniowiecznego zamku królewskiego w Poznaniu [in:] Średniowieczna architektura sakralna w Polsce w świetle najnowszych badań, red. T. Janiak, Gniezno 2014.

Ratajczyk T., Nowy zamek w Poznaniu – negatywny przykład adaptacji reliktów średniowiecznej architektury [in:] Zamki w runie – zasady postępowania konserwatorskiego, red. B. Szmygin, P. Molski, Warszawa-Lublin 2012.

Tomala J., Murowana architektura romańska i gotycka w Wielkopolsce, tom 2, architektura obronna, Kalisz 2011.