History

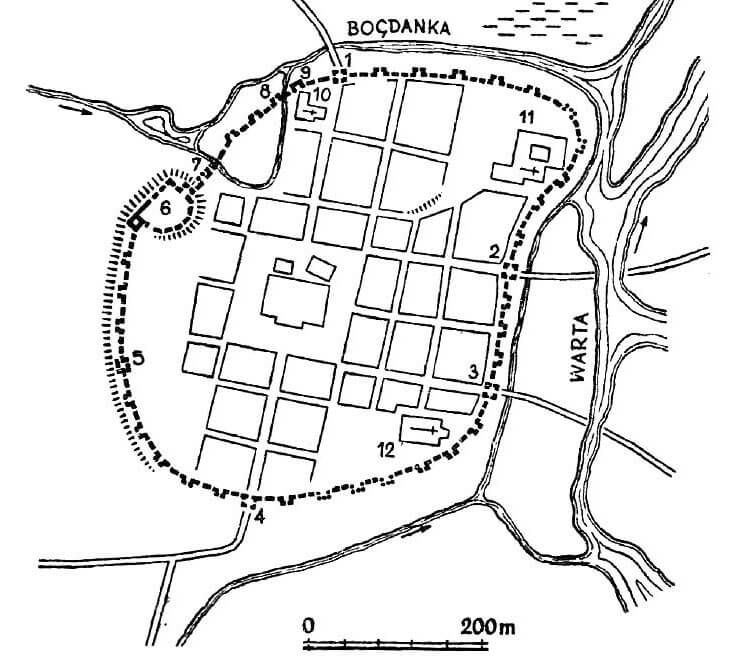

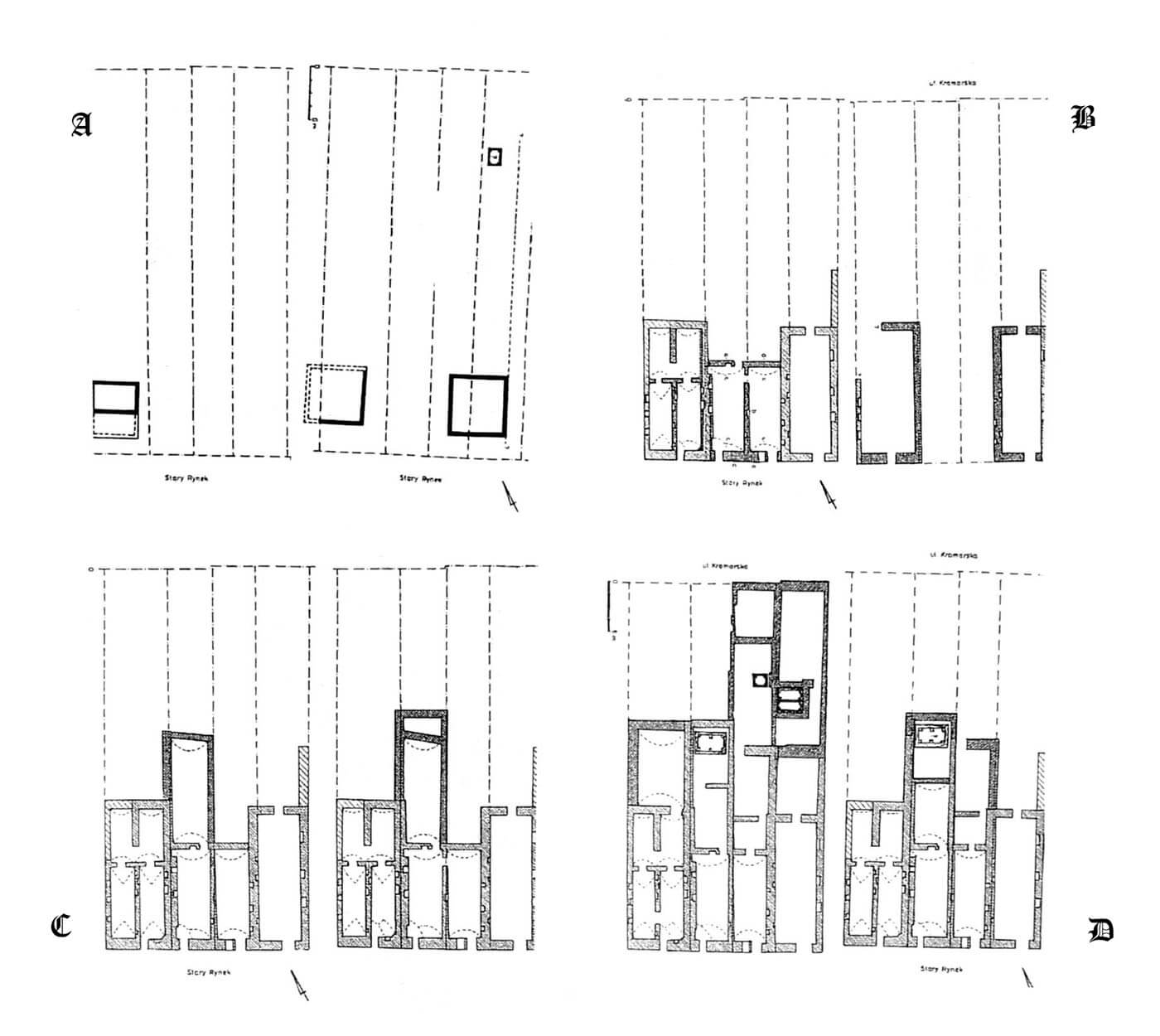

The yard constituting the Old Town Square was marked out around 1253 along with the relocation of the population from the stronghold in Ostrów Tumski and the foundation of the left-bank town near the older settlement of St. Gotthard. The original wooden buildings in Poznań, both residential, commercial and market, began to be replaced by brick buildings since the 14th century, and the pace of their construction increased only after the great fire in 1471. Around 1280, the layout of the centrally located commercial buildings was already developed. In the following years it was expanded and transformed into a brick one, including the Scales House in addition to stalls.

In the town foundation privilege from 1253, Prince Przemysł I imposed on the townspeople the obligation to establish appropriate measures and weights, which resulted in the need to build a brick building of the municipal scales in the second half of the 13th or at the beginning of the 14th century. In 1386, King Władysław Jagiełło granted the city a privilege, under which Poznań obtained the right to build a brick cloth hall. It replaced the older, wooden ones, as the residents of Poznań had the right to erect commercial facilities from 1280, although construction works on the brick cloth halls were probably delayed until the 15th century. They were first recorded in 1499, while in 1435 the Scales House was recorded for the first time. The new seat of the latter was to be erected by the municipal scribe Marcin around 1442 – 1453 or 1470.

In the first half of the 15th century, a group of narrow houses was erected south of the town hall. These houses, or as they were originally called – Herring Stalls, belonged to slightly poorer merchants, unlike the patrician houses in the frontages of the market square. At the beginning of the 16th century, some of them received brick arcades, and in 1534 the city authorities agreed that the building guild should erect arcades for all houses. Then, over time, the arcades were walled up, creating small shops. In the 16th century, due to the increase in the number of inhabitants, the process of renting out old cloth stalls, converted into tenement houses, was also taking place.

In the second half of the 16th century, tenement houses and market buildings began to be transformed in the Renaissance style, while in the 17th and 18th centuries they received Baroque forms, while the original, still medieval layout was preserved. The central block and the surrounding tenement houses were almost completely destroyed during World War II as a result of fires and artillery shelling. After the war, most of the buildings around the market square and some of the downtown buildings were reconstructed, but they were restored to the form obtained in early modern times.

Architecture

The Old Market Square in Poznań was laid out on a square plan with a side of about 140 meters, on which each frontage was originally divided into 16 equal plots, and in the central part of the market square there were the town hall, Scales House, cloth halls, bread, shoemaker and butchery stalls. On each side of market square there were three streets, between which there were 8 long and narrow plots of land. Situated in the center of the city of 21 ha, the market became the domain of trade, to which its buildings were adapted, while the craft production was concentrated in the streets, and even for hygiene reasons, partly outside the defensive walls (Garbary settlement).

The oldest buildings near the market square from the period after the town was founded were erected in log and timber-framed structures. They were single-space buildings, probably one or a maximum of two storeys, derived from rural and homestead buildings, adapted to new urban conditions. Some of them probably stood as detached houses, surrounded by lighter farm buildings. The buildings were formed in relation to the regulatory lines, on the front parts of the plots, but at a distinct distance from the facades of later tenement houses.

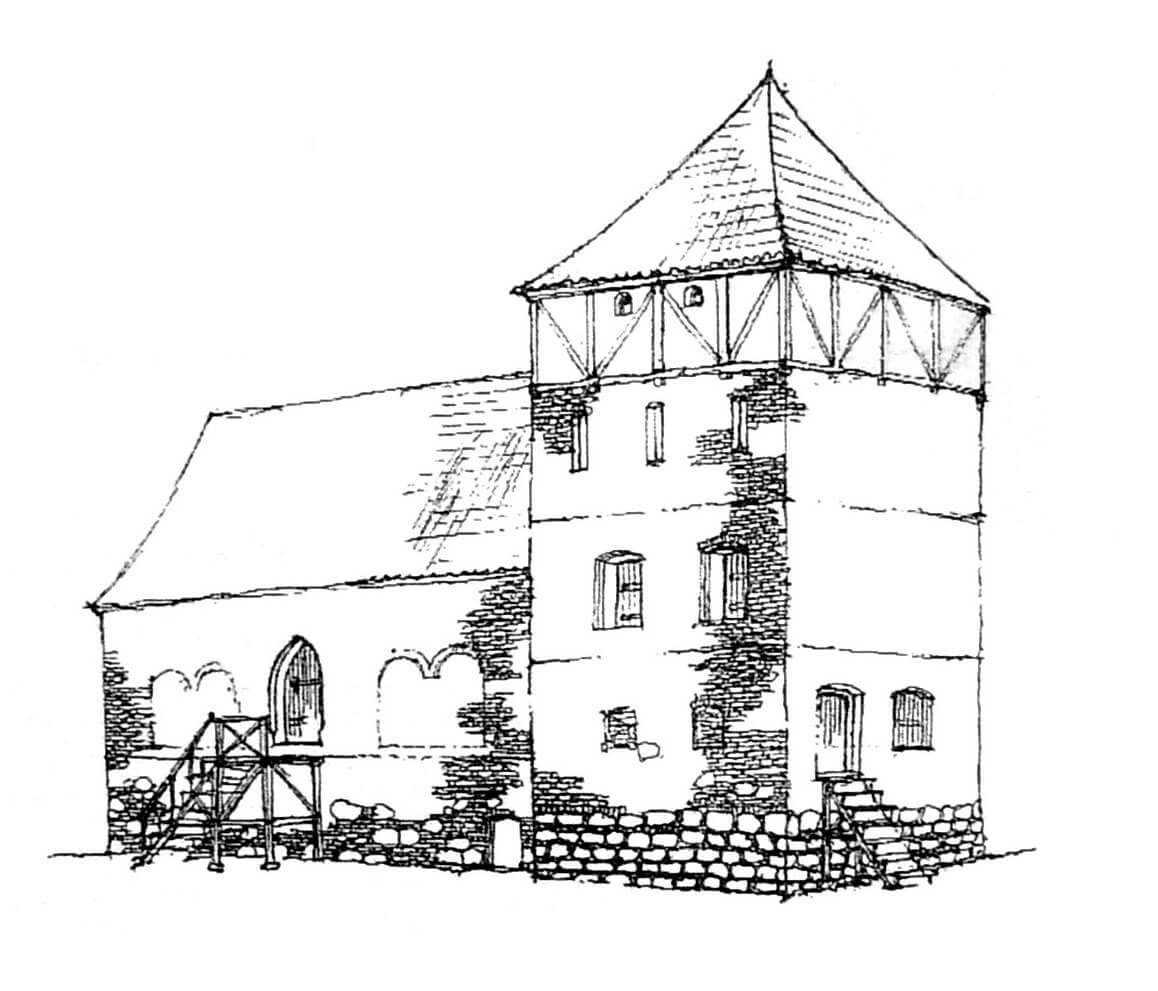

Among the oldest buildings, the brick building at number 48, identified with the seat of the commune head, stood out from the very beginning. It had a tower character, as well as an exceptionally deep foundation, different from other Poznań houses. It was built of bricks with a monk bond on a stone foundation, and at the end of the fourteenth century it was enlarged by a second part, made of bricks in the Flemish bond. The rear part, four storeys high, continued the form of the original tower house. It was much higher than twice as long, but at the same time clearly lower, only two-story front part of the building. At the end of the fifteenth century, the building was finally fitted into a compact, row-by-market building, which resulted in the removal of side entrance portals and leaving only one on the axis of the facade from the side of the market square.

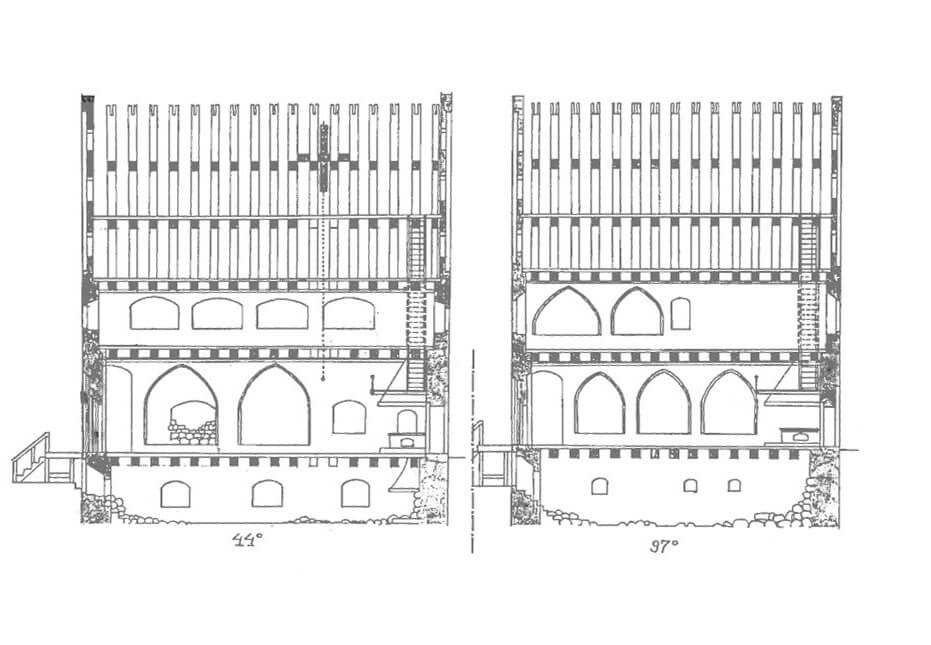

The oldest brick houses in Poznań from the end of the 14th century were usually two-story, initially without a basement, but with a low, partially under ground floor, above which there was a large, high hall, covering the entire second floor, from 4 to over 5 meters high. These halls were decorated with relatively large pointed-arched recesses in the longitudinal walls and sedilla recesses, which were a natural background for the paintings. From the very beginning, the interiors of the houses of wealthier burghers were not only utilitarian, but also representative. All rooms were covered with timber, beam ceilings. Vertical communication was initially organized probably by means of ladder stairs and hatches in the ceilings, then in the thickness of the rear walls. A kitchen devices were usually placed next to these walls. The interiors were separated by wooden or timber-framed screens, often planned when erecting brick neighboring walls. Attics were often equipped with lifting devices, as they were intended for storage purposes

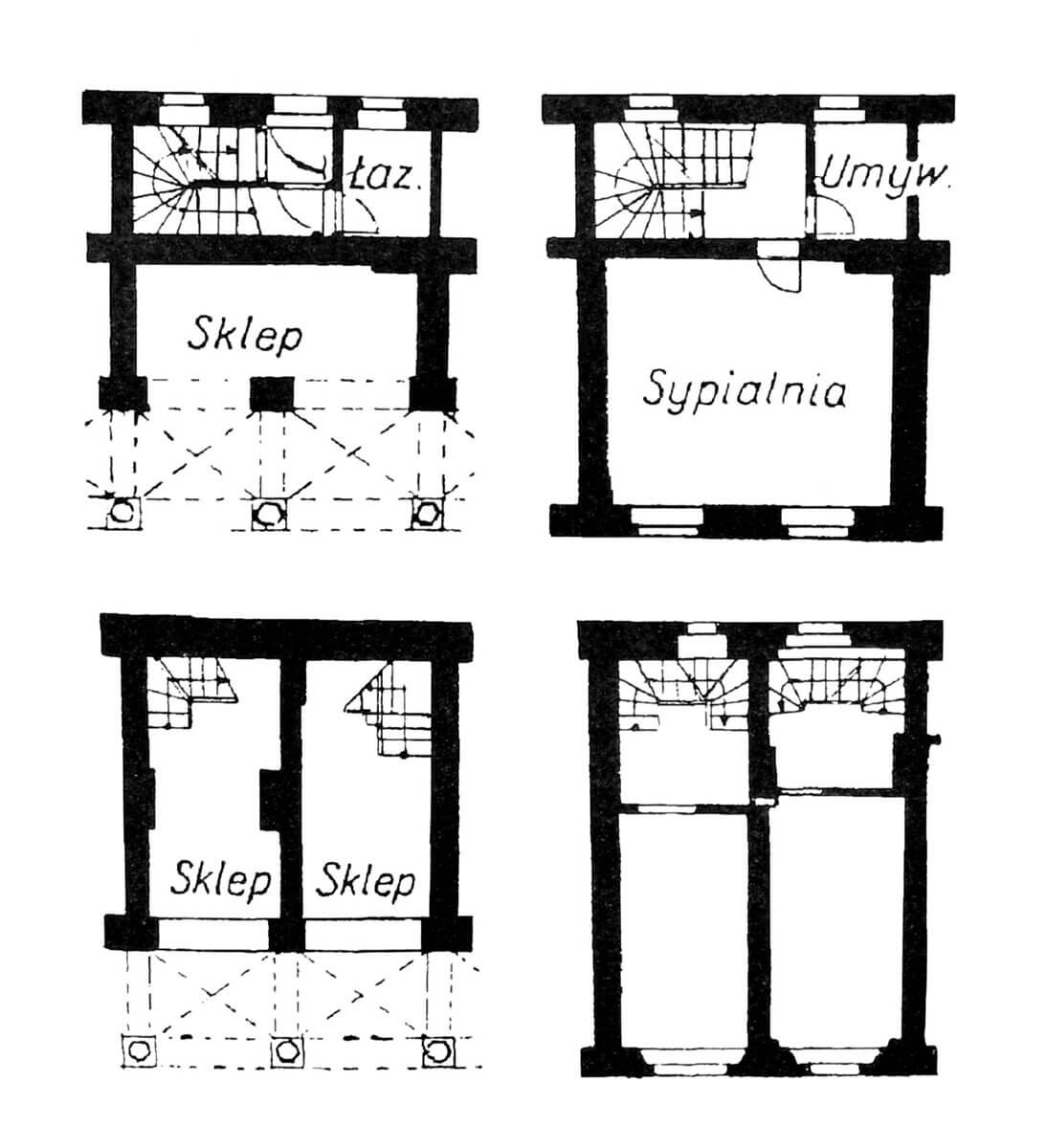

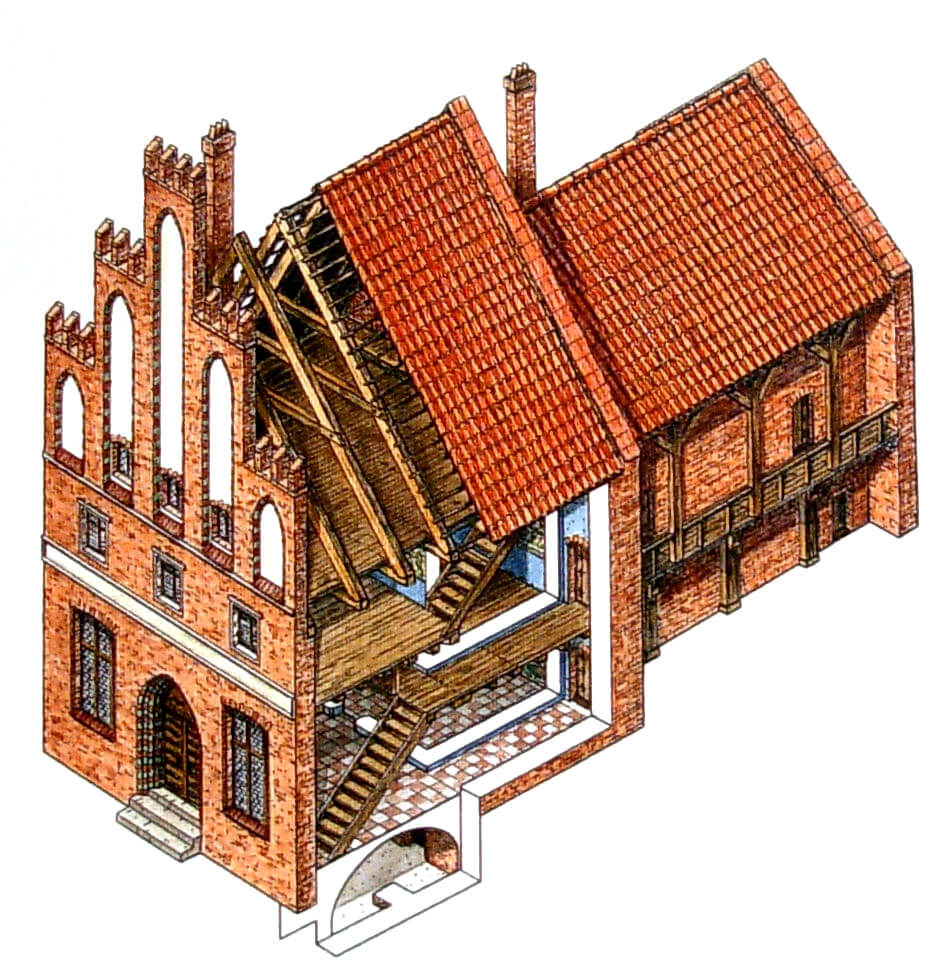

The brick tenement houses at the Poznań market square from the 15th century had two, and later three bays, were usually already three-story, arranged in compact buildings, faced with decorative stepped gables filled with blendes to the market square. These houses were erected on rectangular plans with dimensions of about 7-9 x 24-28 meters. As a result of raising the ground level, the original rooms on the ground floor began to serve as basements with economic and storage functions, while the former floors took over the functions of the ground floors. The raised floors were residential and representative. On the ground floor of the buildings, from the front, there was usually a large hall with a representative and service character. Initially, the shorter rear bays, as well as the front one, were single-space. Later, however, a low passages and a back rooms were separated from their ground floor. The problem of founding a partition wall in parts adapted for cellars was initially solved by building massive wall pillars. It became the rule to base these divisions on ogival arcades. There were living and storage rooms on the upper floors. The great room (magna stuba) situated on the first floor of the back bay was of particular importance among the rooms of a typical tenement house near the market square. Usually especially architecturally distinguished, e.g. by the use of wall panels or sedilla recesses, it gathered the most valuable equipment, as well as family heirlooms. The interiors in the Gothic period were covered with wooden ceilings, also with cross-rib vaults, and then stellar and diamond vaults were also used. The equipment and architectural details included wall recesses framed with moulded bricks, pointed, straight or ogee arched window and door jambs, tiled stoves, and fireplaces. Some houses had steam baths. In the back of the front tenement houses, separated by a small yard, there were warehouses and workshops.

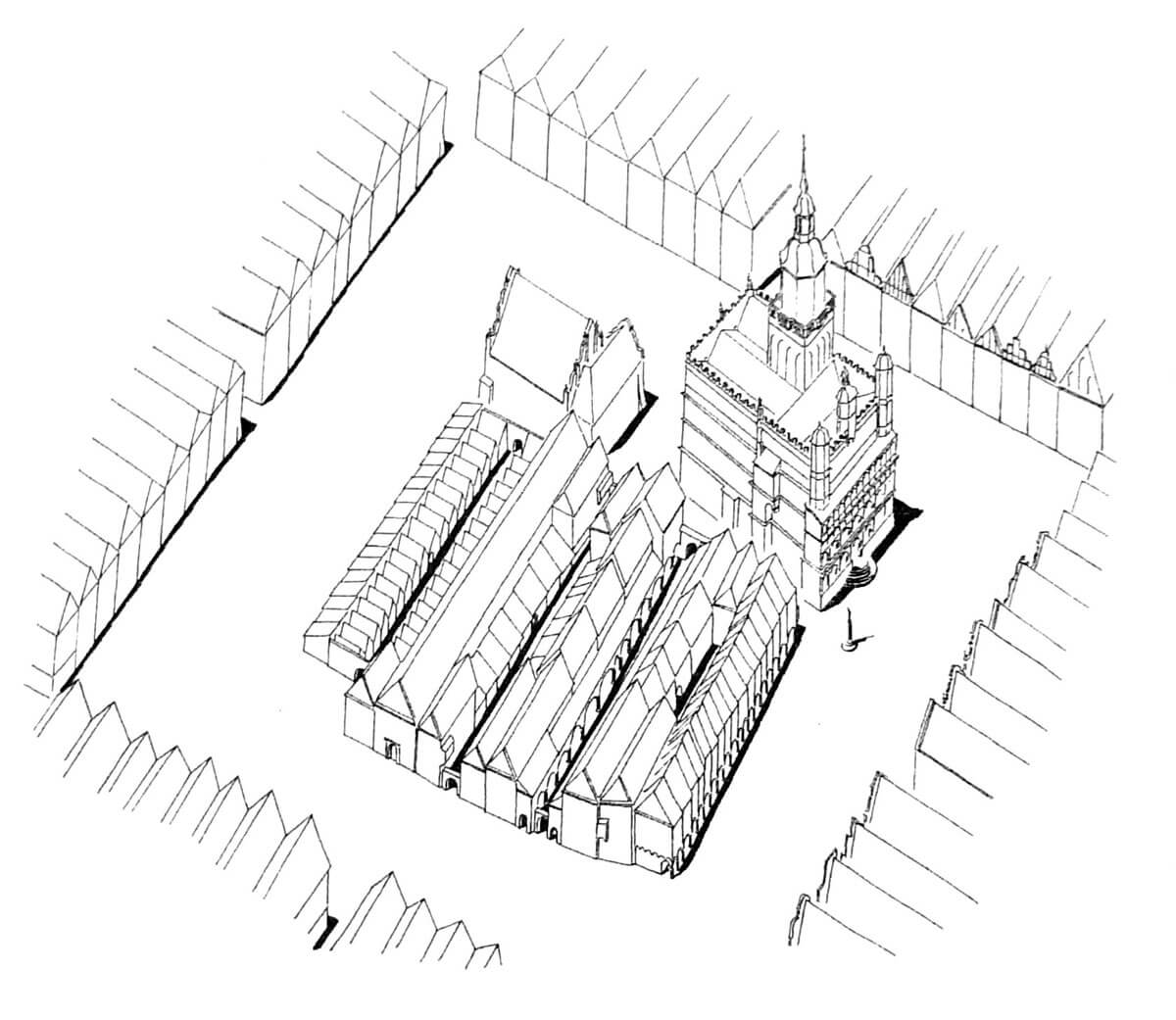

In the middle of the market square, south of the town hall and the municipal Scales House, there was a complex of several-row, initially one-story, butcher’s, shoemaker’s and bread stalls, cloth halls and other stalls, separated by north-south streets. The eastern one, called Hen’s Leg, about 2.5 – 3 meters wide, was closed with two gates. More or less in the middle of the complex there was a slightly wider street called Garland, also with entrances from the north and south, and in the western part there was Velvet street. In addition, narrower transverse passages functioned to facilitate communication.

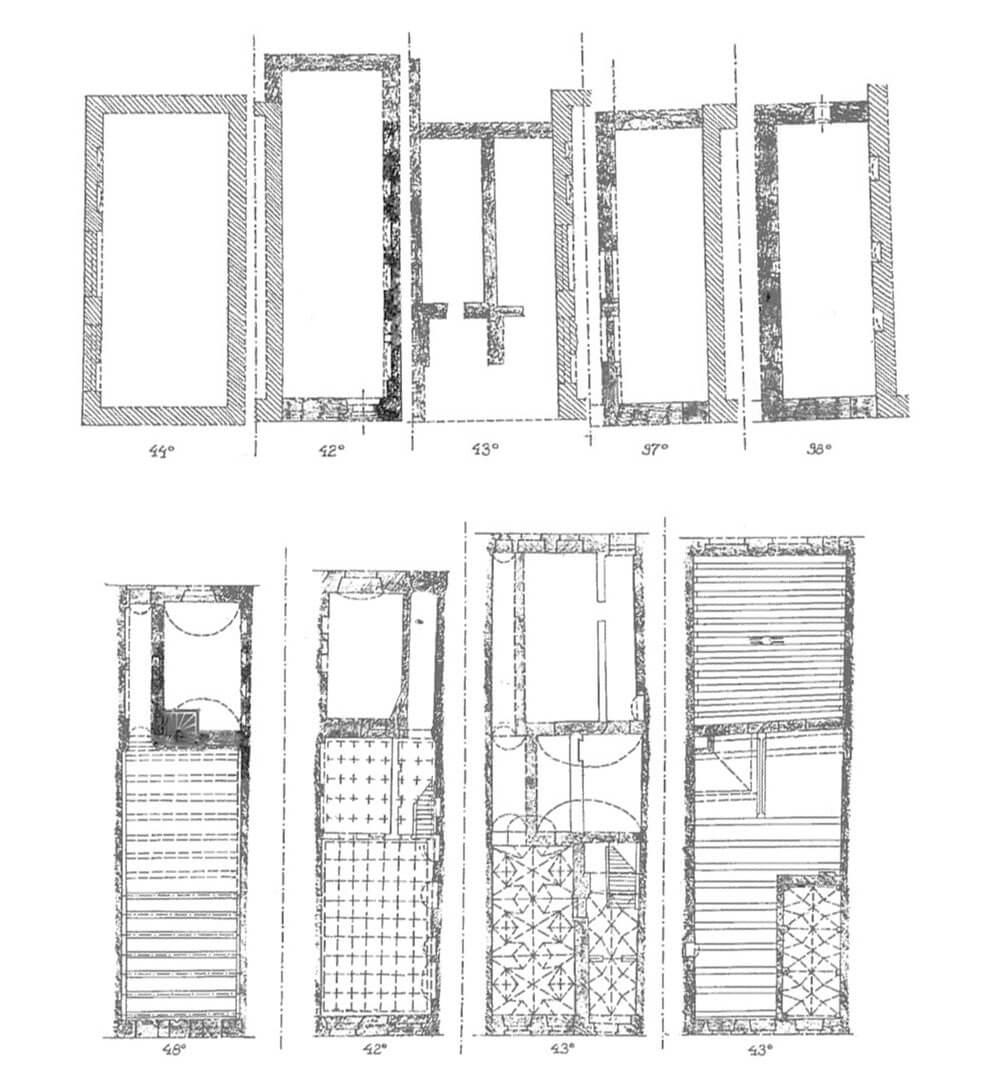

To the south of the town hall, in the eastern part of the central block, there was a row of initially one-story, and from the 15th / 16th century three and four-storey narrow tenement houses, originally called Herring Stalls. In the 15th century, there were seventeen of them, built on quite regularly marked out plots 2.5-2.8 meters wide and about 6.6 meters deep. Their facades in the first half of the 16th century were supported by sandstone columns that supported the arcades under which fish, candles, torches and salt were once traded. Many of the columns still had Gothic forms, with octagonal stems and Gothic accents in the capitals. The columns were positioned in the line of the front wall of the tenement houses, so that each one carried the arcades of two neighboring tenement houses. The exception was the wider tenement house no. 20 distinguished by three columns, probably enlarged by a passage into the market buildings, which operated next to it, at least since the 15th century. The two corner houses were also wider: the southern and the northern one, the only ones that could be enlarged at the expense of the market square.

The interiors of the Herring Houses were similar to each other, only the corner ones, using a larger area, had a different interior layout. Most often in the ground floor, after separating the arcades, there were rooms with dimensions of about 4.7 x 2.3 meters. They were covered with wooden ceilings, and in the rear part had staircases leading to the floors. The front part was intended for commercial premises, and the sale took place under the arcade. For this purpose, there had to be doors and windows in the front wall. Basements served as a warehouse, while the upper floors were intended for residential purposes quite early, with the first floors having halls with fireplaces, most likely serving as kitchens. They were lit by small windows in the back walls of tenement houses. The lowest of them were set at a height of as much as 3 meters due to the rear row of buildings.

From the beginning of the 15th century, the back of the Herring Houses was occupied by a row of 40 shoemakers’ shops, initially low and probably wooden, with time raised and rebuilt, ending in the south with a town scribe’s tenement house from the first half of the 16th century. It was a three-story building, with a basement, facing the south side of the market square with its gable, probably equipped with a bay window, covered with a gable roof. Inside, the basement and a part of the ground floor had vaults, while the upper storeys were separated by timber ceilings. In the ground floor there was a large room and a passage to the courtyard, to the shoemaking area, and on each floor there was a front room and a spacious hall with a kitchen niche and a back room on the first floor. Overall, this tenement houses probably resembled a typical Gothic burgher tenement houses from the front plots of the market square. From the north, the row of shoemakers’ houses was ended with a shoemaker’s fraternity tenement house, probably two-story, equipped with a bay window based on a massive stone console.

The second row of shoemakers houses, separated by a street on the north-south line, was on the west side, i.e. at the eastern wall of the cloth hall. The cloth hall was also situated in two rows of stalls-tenement houses separated by a street: eastern and western. Initially single-storey, wooden, were transformed in the 15th and 16th centuries, especially on the edges, into typical Gothic brick tenement houses with vaulted basements (referred to in the 1530s as domus and domuncula). Soon, also in the central part of the complex of cloth stalls, higher storeys began to be built, gradually taking the form of brick residential buildings, which resulted in huge disproportions in the appearance, dimensions and usable role of individual cloth stalls. At the end of the Middle Ages, there were about 10 of them in the eastern row and 12 in the western row. They were not closed at night, but accessible to everyone as a public street. Some lacked the arcades and cobblestones recommended by the city council. Those stalls with arcades, had them only in the form of roofs protruding in front facades, only corner cloth stalls had brick arcades. The alley between two rows of cloth halls was never covered with a roof.

Rich (silk) stalls, occupied by cloth cutters, were adjacent to the western wall of the cloth stalls. They were similar in appearance to the shoemakers’ shops and cloth halls: they were grouped into two rows on both sides of the street, initially low and wooden, at the end of the Middle Ages made of brick and raised. However contrary to the eastern part of the inner-market buildings, which was often mentioned by the city council, they were better organized and less diverse. In 1539, there were 28 rich stalls, divided asymmetrically by a transverse street (six in the northern part and eight in the southern part).

In the western part of the center-square complex, there were bread stalls and a butcher’s shops on the very edge of it. The original two-row stalls of bread benches in the years 1535-1540 were replaced by an elongated, one-story building about 59 meters long and 8.5 meters wide in the southern part (in the northern part, the width narrowed to 7.7 meters). It was raised around 1559 by an upper storey housing a smartuz, i.e. a group of stalls intended for needlework, cap makers and purse makers. From time to time, the building was also used as a grain store and a storehouse for visiting merchants. Its interior was covered in eight bays with cross vaults, with two rows of bakery benches arranged along both longer walls of the hall building, with a passage on the axis and perhaps a narrower transverse passage. The upper storey was covered with an open roof truss.

Near the building of the bread stalls, in its southern part, there was a cloth cutting building. It was a small house with dimensions of 5.6 x 7.1 meters, three-story, with a cloth cutting room on the ground floor, two rooms and a kitchen on the first floor, two rooms and a smaller room on the second floor. From the fifteenth century, there was also a second cloth cutting building, located on the opposite side of the complex, at the Scales House, near the town hall. The Scales itself was a building on a short rectangular plan, two-story, with a high gable roof, facing the front and the entrance to the west (the building was first recorded in 1471). Its ground floor was used for commercial purposes, while the first floor (the so-called lord’s chamber) was heated by a fireplace, and perhaps used for meetings of municipal authorities.

Butchery shops functioned already from the second half of the 13th century as a two-row, initially wooden complex of stalls, which were entered from the north and south, and by side entrances from the east and west. To the west, they were adjoined by a row of lighter stalls for tanners, then cap makers, and then potters. The brick form, consisting of 18 plots in one row, was obtained by butcher’s shops after 1535. They were covered with roofs perpendicular to the north-south axis, while the lighting was provided by dormers or hatches in the roof slopes.

In total, on the area of about half a hectare of the medieval market, about 200 sales stands, grouped in seven industry complexes, were placed. About 34 of them were available directly from the market, and the rest had 12 entrances (five from the south, five from the north, and one each from the east and west). The food trade in the western part of the block was probably deliberately concentrated, and the cloth hall and rich stalls, due to the high value of goods, were placed inside the block. Thanks to this, the greatest pedestrian access was achieved, on the shortest road connecting the gate’s streets: Wrocławska and Wroniecka. On the edges, herring and tannery stalls representing poorer branches of trade were grouped in the rows open to the market.

Current state

Due to the history of this place, most of the houses and buildings located here have been rebuilt, restored or modernized. Worst of all action took place during World War II, where most of the buildings were destroyed. However, some of the tenement houses have retained original Gothic cellars or fragments of walls now hidden under later redevelopments, and some have been reconstructed in reference to the original appearance.

bibliography:

Banach B., Przemiany zabudowy miasta lokacyjnego w Poznaniu [w:] Civitas Posnaniensis. Studia z dziejów średniowiecznego Poznania, red. T.Jurek, Z.Kurnatowska, Poznań 2005.

Gałka W., Z badań nad najstarszą zabudową mieszczańską Poznania lewobrzeżnego (XIII-XV w.), „Kronika Miasta Poznania”, nr 4, Poznań 1999.

Pazder J., Poznań. Stary Rynek, Poznań 2001.

Rogalanka A., Theatrum pośrodku rynku. Zabudowania targowe na rynku średniowiecznego Poznania, Poznań 2017.

Tomala J., Murowana architektura romańska i gotycka w Wielkopolsce, tom 3, architektura mieszczańska, Kalisz 2012.