History

The founders of the castle and the town of Allenstein were representatives of the Warmia chapter. After the division of the Prussian lands into dioceses in 1243, the first bishop of Warmia, Anselm, received the third part of the territory of the diocese, as the bishop’s dominion, where he performed ecclesiastical and secular authority. From this area he was obliged to divide the third part to the chapter, that is, the college of canons advising the bishop and taking care of the cathedral. The process of transferring the territories to the chapter lasted a long time, Anselm’s successor, bishop Henry Fleming gave it the Frombork and Melzak’s komornictwo (kind of county), and it was not until 1346 that bishop Herman from Prague assigned the largest Olsztyn’s komornictwo to chapter. The chapter then began to develop its lands, conducting a settlement campaign, locating new towns and villages, building mills, sawmills, brickyards, inns and castles, as being part of the Teutonic state, it was obliged to protect its possessions and assist the Teutonic Knights during warfare.

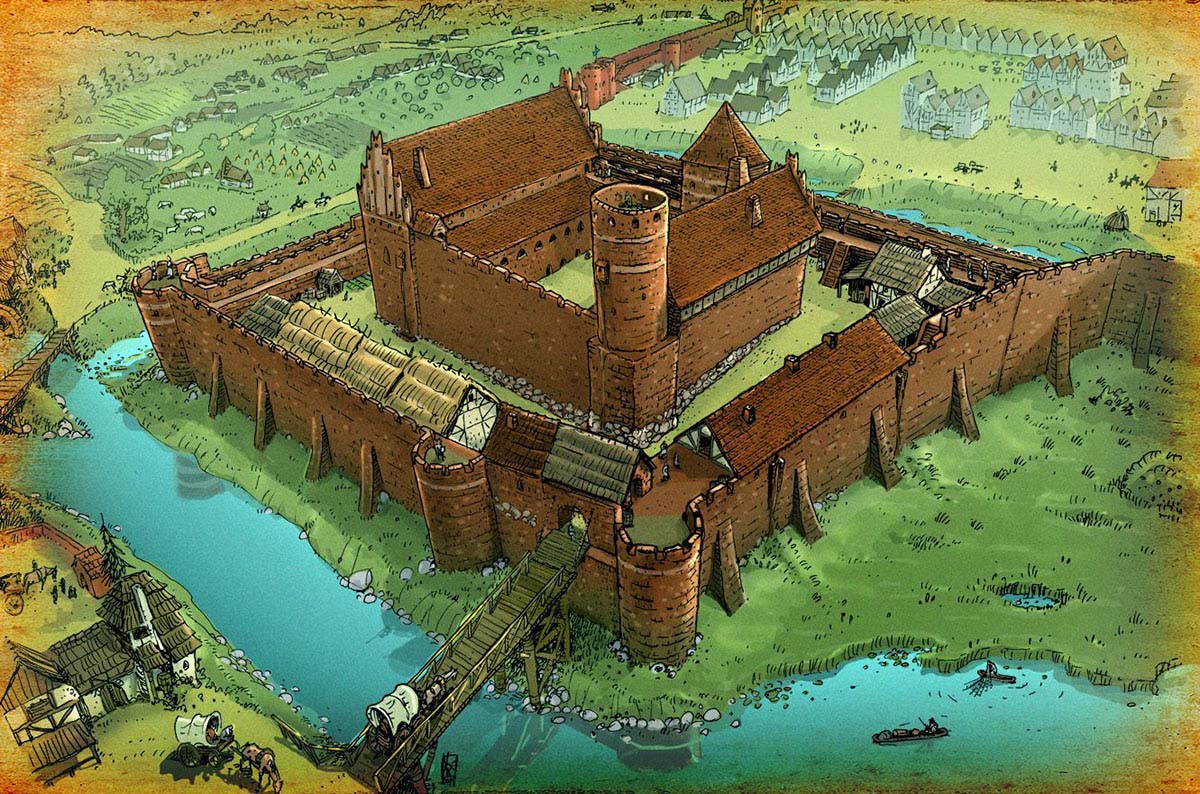

The construction of the castle in Olsztyn began around the middle of the 14th century as part of the colonization action of southern Warmia. The first time it was mentioned in documents in the town charter, issued in 1353. It was to become the seat of the administrator of the chapter lands and a safe place to store the treasury. Initially, the castle consisted of one residential wing on the north-eastern side of the courtyard, completed around 1373. The economic wing of the castle was added or expanded at the beginning of the 15th century, probably due to the determination by the chapter, yet at the end of the 14th century, of the size of the grain reserve stored in the castle (it was to be 60 lasts). The tower from the mid-fourteenth century, was rebuilt in the early fifteenth century, in a round shape on a quadrangular basis. At the same time, the castle walls were raised and supplemented with the second lower belt of fortifications. The wide scope of construction works was probably a significant burden for the local population, as evidenced by the letter of the Grand Master of the Teutonic Knights to the administrator of the chapter estates from 1429. The Prusians were to complain about the obligation to work for the Olsztyn castle, to which they were not obliged according to their privileges. Obligatory service could include trees felling in the winter of 1428-1429 and the transport of wood to the castle.

The castle played a significant role during the Polish-Teutonic wars. In 1410, after the Battle of Grunwald, bishop Henry Vogelsang paid homage to the Polish king. However, the Polish crew remained in the castle only for two months, and after the withdrawal of Polish-Lithuanian troops, Warmia returned to the Order. In 1414, the town and the castle, despite receiving the Teutonic support, were captured by Poles after a few-day siege. The king occupied the stronghold with the crew under the command of knight Dzierżek from Włostowice and went further north. However, also this time, the Polish troops remained for a short time, because in the same year Olsztyn was recaptured by the Teutonic forces, led by the commander from Pokarmin, Helfrich von Drahe. During the Thirteen Years’ War the castle passed from hand to hand. In February 1454, the rebel townspeople wanted to attack the castle and demolish it, but after receiving the keys, they took it and made an important fortress of the anti-Teutonic union. After the defeat of the Polish knights at Chojnice in September 1454, the situation reversed and Olsztyn was without a fight, as a result of negotiations, returned to the Order. In the years 1455-1461 the castle was managed by the Teutonic mercenary knight, Georg von Schlieben, who appropriated the treasury of the chapter and castle property. Finally, after the Second Peace of Toruń ending the Thirteen Years’ War, Warmia together with Olsztyn was incorporated into Poland.

Teutonic Knights threatened the castle and the town for the last time in 1521, but the defense was so effective that they stopped after one failed assault. The chapter entrusted the management of the Olsztyn Castle to a canon, elected from among its members, known also as the administrator. In the years 1516-1521, the administrator of the Olsztyn was the great astronomer Nicholas Copernicus. He has just prepared the defense of Olsztyn against the Teutonic invasion. He gathered supplies of ammunition and provisions, doubled the number of the castle crew.

In the 16th century, the castle was visited by Marcin Kromer, who then consecrated the chapel of St. Anna, recently built in the south-west range of the castle. Over time, both wings lost its military significance, and became less convenient for residential purposes. In 1758, the castle was connected by the road with the town and a Baroque palace wing was built from this side. At the same time, the outer bailey and part of the walls were liquidated.

After the annexation of Warmia in 1772, the castle became the property of the management of state estates. In 1845, the bridge over the moat was replaced with a dyke joining the castle with the town, while the moat was drained. In the years 1901-1911, in connection with the election of the castle as the seat of the president of the Olsztyn regency, a general renovation of the castle was carried out, while some elements were transformed. In 1921, a museum was placed in the rooms of the castle.

Architecture

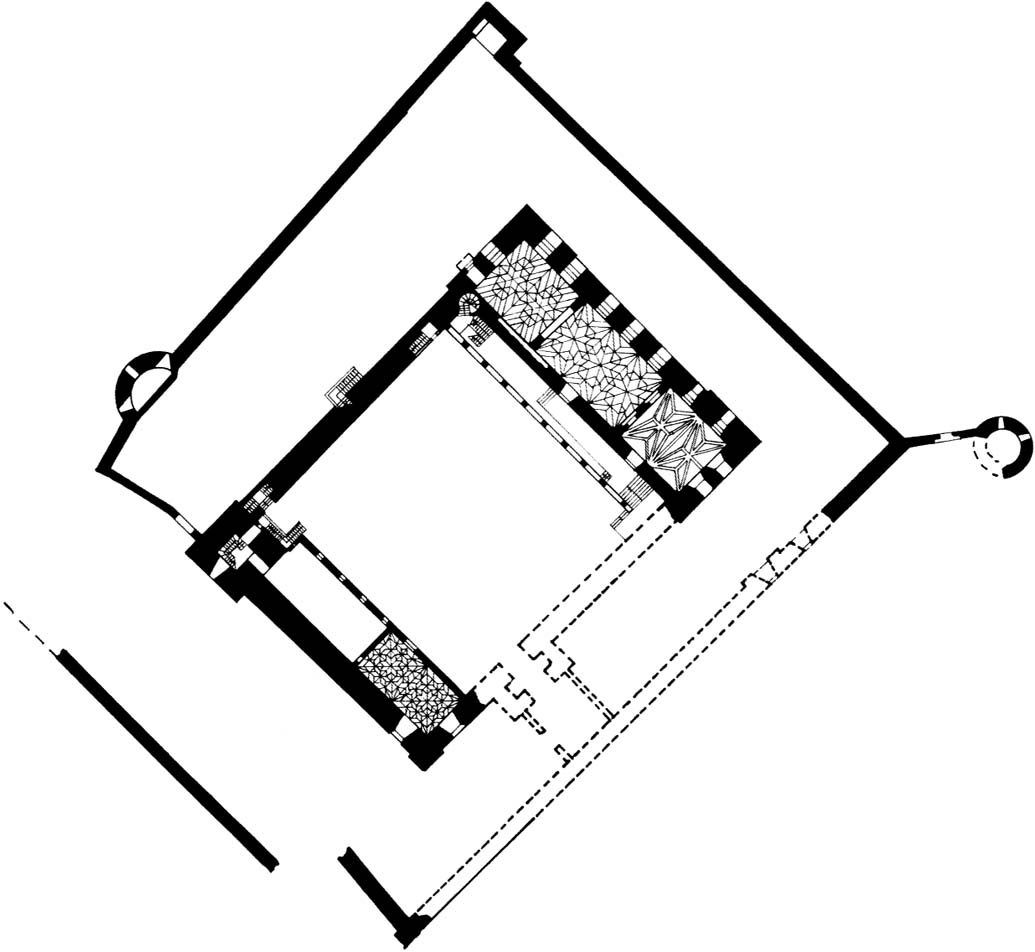

The castle was erected in a naturally defensive place, on a hill in a wide bend of Łyna. The town developed on its south-eastern side, also in the bend of the river. On the other side, from the north-west, a castle’s farm was founded, and at the foot of the castle on the river, a mill. Farm probably played the role of an outer ward, through its area led the way to the castle. The town and the stronghold were separated by a moat, powered by the waters of Łyna.

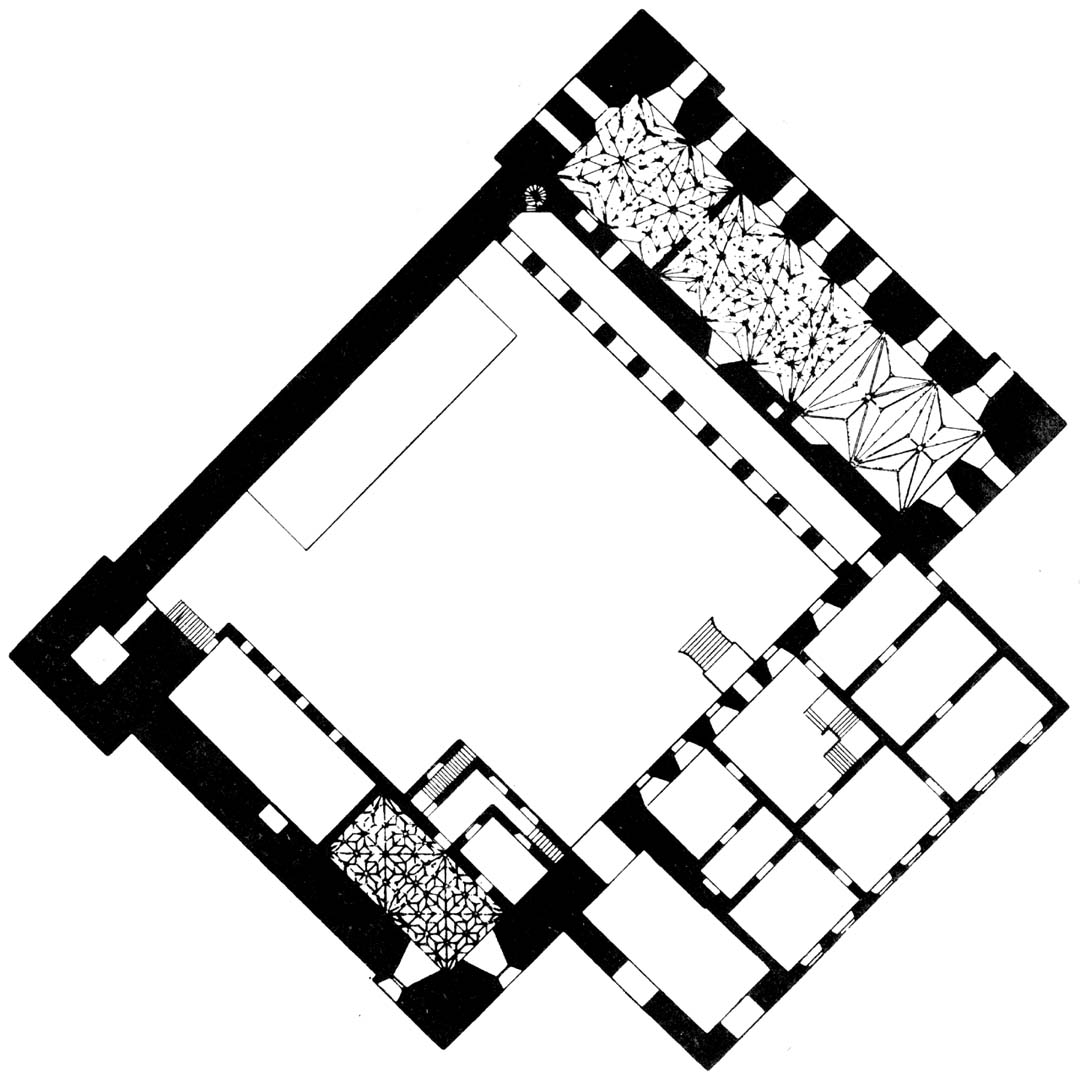

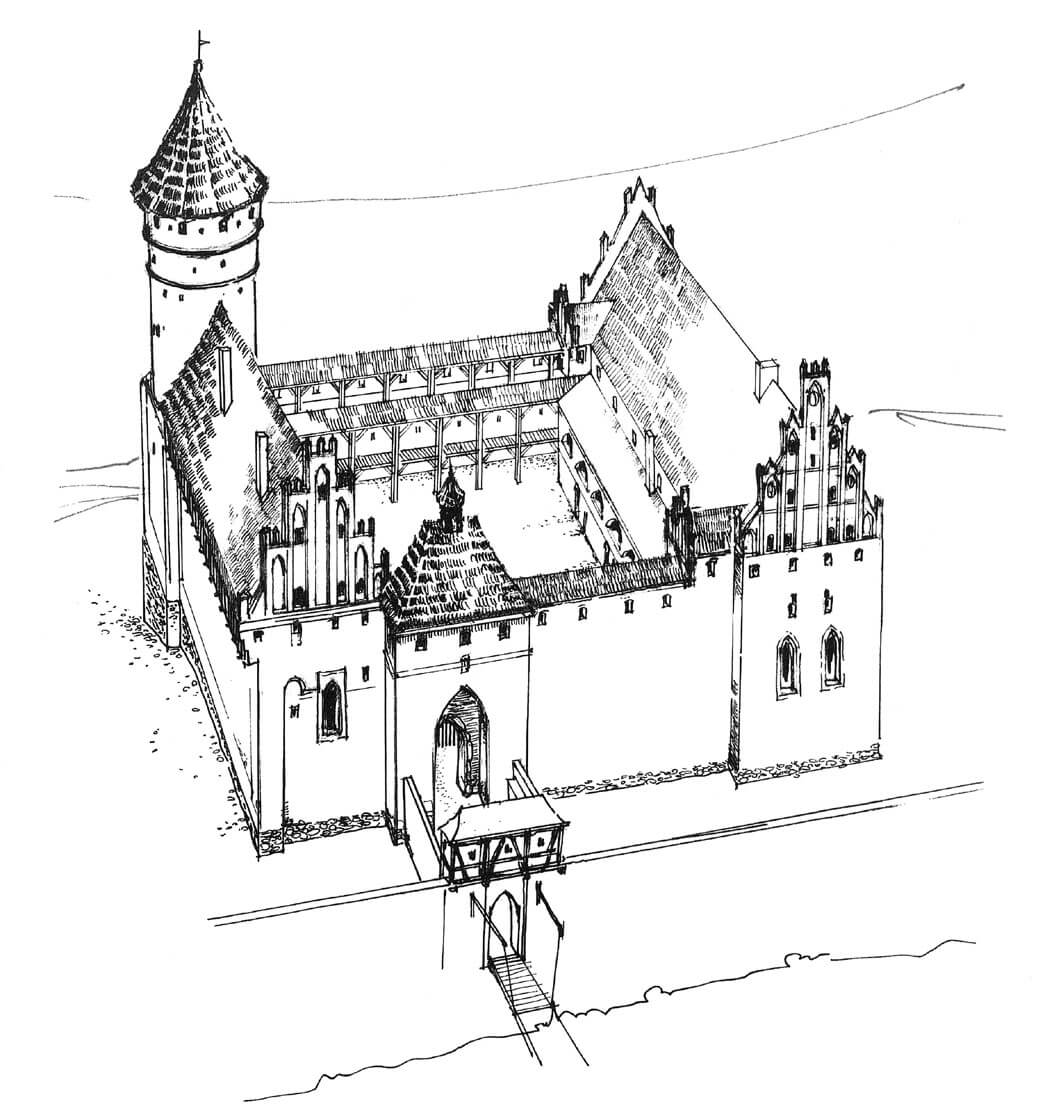

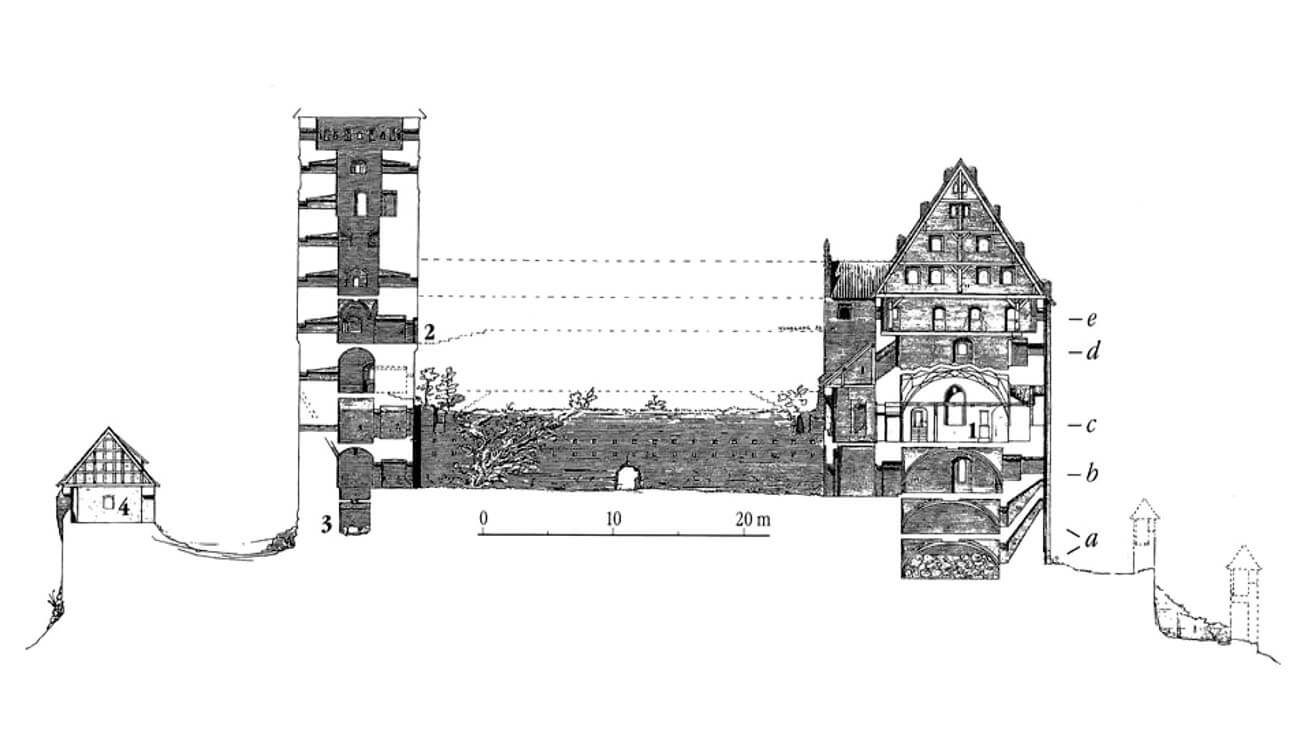

The castle was built of bricks on a stone foundation, on a rectangular plan formed by massive curtains, up to 3 meters thick. Its oldest part was the main north-eastern residential house. In the 70s of the fourteenth century, a square tower was placed in the west corner, towering over the crossing over the Łyna River, and initially a low building with a single-pitched roof, of economic and perhaps administrative functions, at the south-west curtain. The entrance gate to the courtyard was located in the eastern curtain. In the last decade of the fourteenth century and the first quarter of the 15th century, the perimeter walls, the tower and both opposite wings were raised. Also in the 15th century, the external wall was built with the Lower Gate, preceded by a bridge over Łyna. The circumference of these walls was reinforced with cylindrical towers, and the castle, with the preservation of strategic and communication autonomy, was connected with town fortifications.

The main house eventually took the form of a four-story building with two stepped gables crowning the shorter sides. They were decorated with pinnacles and ogival blendes, pierced with circular openings and topped with small gables with crockets. The plaster of the gables was covered with painted tracery decorations, typical of the Gothic architecture of Warmia region. From the side of the courtyard, two-story cloisters adjoined the building.

The layout of the rooms was modeled on the Teutonic sites, although the representative rooms were relatively low in Olsztyn. Extensive cellars were grion vaulted and reinforced with additional arch bands. In the western part, cellars had two levels. The ground floor rooms had also originally groin vaults, there was an armory, a pantry and a administrator’s of the castle chamber. Below, in the cellars’ level in a separate room, the treasury was probably placed. On the first floor there were: a residential chamber of the administrator with a latrine, a three-bay refectory and a two-bay chapel of St. Anne on the east side. The refectory and the administrator’s chamber in the years 1510-1520 received magnificent diamond vaults, each of them with a different form and geometry, and the chapel stellar vault. The third and fourth storeys were single-space with a defensive porch running around. An interesting and unusual solution was to place the lift shaft at the height of the refectory. Goods were pulled up to the higher levels by ropes. On the representative floor you could get from the cloister, which was also connected with the defense porch at the north-west defensive wall. The upper floors could be reached by round stairs placed in the thickness of the wall. After raising the main house by the fourth floor, the new defensive floor was higher than the guard’s porch of the curtain wall, connecting the house with the corner tower. Probably for its communication, a higher defensive wall was added to the building, placing a passage in it, and the resulting superstructure was crowned with a small, Gothic gable.

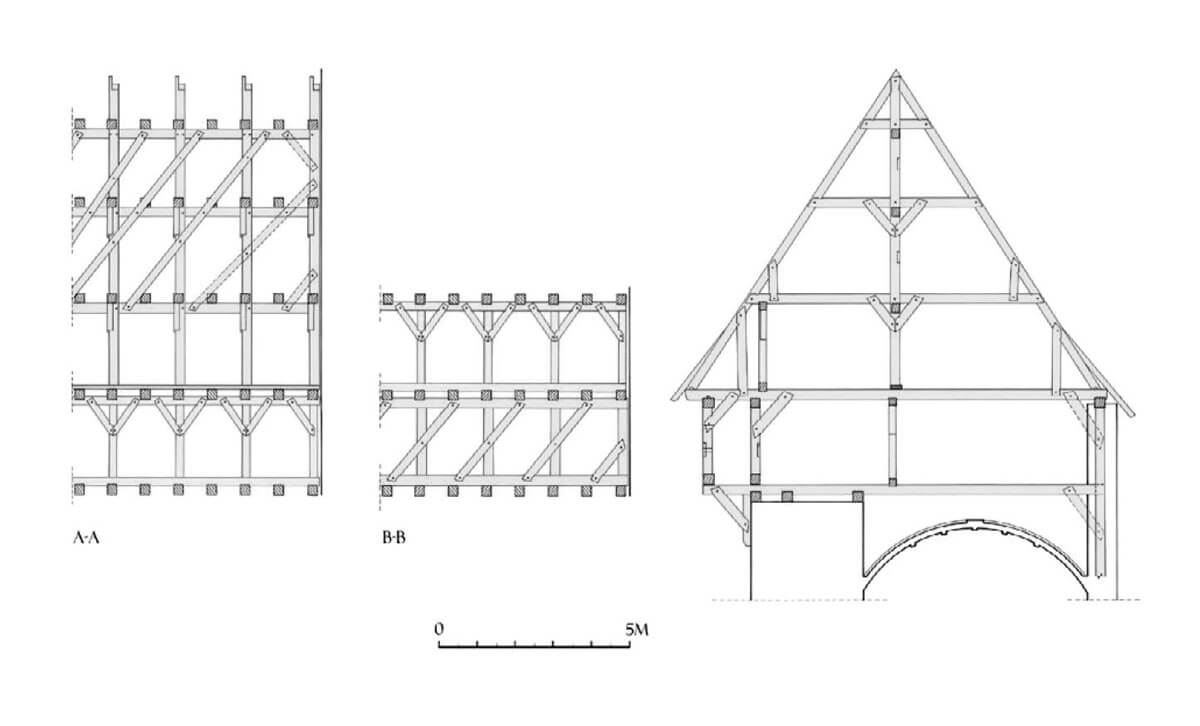

In the first quarter of the 15th century, the south-west wing was rebuilt and raised to accommodate four storeys of warehouse and residential functions. Eventually, it reached the same height as the main house, but had a lower roof due to the narrower base. From the side of the courtyard, in the three upper storeys, the wall was made of a wattle and daub structure. As it was less resistant to weather conditions, the half-timber part of the façade was significantly set back in relation to the brick part on the ground floor, and thus hidden under the prominent eaves of the roof. The façade offset created by this could be used for the roof support of the communication porch running along the first floor of the wing. On the other side of the wing, in the face of the curtain wall, a single-storey half-timber wall was built, and behind it another, mounted on ceiling beams protruding in front of the façade, blocked with characteristic catches. In this way, the wing received a full-size usable storey, wider than the lower storeys, and the hoarding porch serving a defense functions over the road to the Lower Gate. The construction of the wing was completed by the erection of gables, with a decorative form especially from the side of the town. The eastern gable, decorated with pointed, plastered blendes, had a chimney in wall thickness. In addition, in the third from the south axis of the gable, openings were made to operate the roofed crane, installed at the level of the second level of the roof truss.

The wattle and daub wall of the wing was rebuilt in bricks in the second half of the 15th century, probably due to structural problems with the statics of the building. As a result of this reconstruction, it became three times thicker, but a half-timbered filling was removed before the brickwork. In the new wall, small window openings, closed with segmental arches, were pierced at regular intervals. Eventually, the reconstruction did not stop the construction problems of the wing, and its wall from the courtyard side did not cease to drop.

The south-west building had no basement. In the ground floor there was a kitchen, a bakery, a brewery with a malt house (equipped with a large chimney, running in the thickness of the former curtain wall), and a watchman’s room at the gate. On the first floor, official chambers and a burgrave’s apartment were created, accessible by pointed portals from the courtyard side, through a two-level timber cloister providing communication. The upper storeys served as a warehouse and defense facility. In 1530-1531, the castle chapel with the sacristy, made by master Nicholas of Olsztyn, was moved to this wing. It was topped with a rich net vault, which resulted the removal of two levels of beam ceilings of the previous storage structures. In addition, large windows closed with ogival arches were made, framed from the outside with whitewashed, rectangular frames, while at the same time bricking up the existing storage openings and the openings of the first residential and administrative floor. The sacristy was placed in an extension above the watchman’s room, while above it, on the second floor, there was the living room of the castle vicar. It was covered with a decorative beam ceiling.

The wattle and daub walls of the hoarding received 17 bays and longitudinal stiffening by means of parallel braces inclined towards the west gable, passing the columns halfway along and connecting the cap (a horizontal beam connecting the main columns from the top) with the sill plate (the lowest beam). The brackets connecting the wall columns with the truss beams were also responsible for the binding of the hoarding walls with the roof trusses. The hoarding from the outside was plastered, and the plaster of the half-timbered filling also covered the hoarding columns from the inside.

The curtains of the walls were topped with wall-walks, and from the outside, the walls could be equipped with hoarding. The corner tower, initially quadrilateral, received a cylindrical, one-story superstructure. It was again raised in the fifteenth century, when it reached nine storeys. On the fifth and seventh floor, there are traces of fireplaces warming rooms, perhaps guards chambers. The residential function of the tower is also evidenced by the relic of the toilet from the side of Łyna. The doors on the first, cylindrical floor of the tower led to the defensive porch of the curtain wall, while the upper storey led to the passage of the south-west range hoarding.

The exact appearance of the gatehouse tower leading to the castle’s inner courtyard is unknown. We only know that it had a four-sided base and had an ogival gate passage. Nearby, from the side of the courtyard, at the south-west wing, the above-mentioned two-story extension was erected, created on an irregular and small plan. Within the second floor and the half-gable, the extension was probably half-timber, which made it imitate the wing. The side elevation, above the first floor, had a shallow overhang characteristic of the Gothic period. The considerable height of the extension with its relatively small area and the overhang of the façade could give the impression that it was a tower-like structure. Around 1530, it, like the wing, was bricked in in place of an older half-timber structure.

Current state

The castle is currently one of the best preserved medieval strongholds in Poland, although in the early modern period a Baroque palace was added on the eastern side and most of the outer defensive circuit has not been preserved. The floor level in the refectory was also changed, the ground floor vaults were removed, window frames were inserted in the cloister and a neo-Gothic staircase was added. Castle now houses the Museum of Warmia and Mazury, and many special events are organized. The permanent exhibition is the exhibition about Nicolaus Copernicus. On the wall of the cloister there is an astronomical experimental board from 1517, probably made by the great astronomer himself. It served to work on the reform of the church calendar. However, in the courtyard you can see the so-called Prussian Lady, an early medieval cult statue. Little known is the fact that hoarding, or a timber porch on the south-western side is an original structure, dated dendrochronologically along with roof truss for 1429. The hours and dates of the castle’s opening can be checked on the official website here.

bibliography:

Architektura gotycka w Polsce, red. T. Mroczko, M. Arszyński, Warszawa 1995.

Garniec M., Garniec-Jackiewicz M., Zamki państwa krzyżackiego w dawnych Prusach, Olsztyn 2006.

Leksykon zamków w Polsce, red. L.Kajzer, Warszawa 2003.

Skarżyńska-Wawrykiewicz M., Wawrykiewicz L., Średniowieczne konstrukcje ciesielskie południowego skrzydła zamku kapituły warmińskiej w Olsztynie. Przyczynek do historii zamku, “Ochrona Zabytków”, 2/2015.

Wagner A., Murowane budowle obronne w Polsce X – XVII wieku, tom 2, Warszawa 2019.