Historia

The first stone church in Nysa was to be founded and consecrated by the bishop of Wrocław Jarosław in 1198, on the site of the alleged, older, wooden temple. It was destroyed in 1241 during the Tartar invasion, and then burned down in 1249, during the battles between Prince Bolesław Rogatka and Henry III. At the beginning of the second half of the thirteenth century, the Romanesque church was rebuilt or erected in its place. At the end of the fourteenth century, this building was already in a catastrophic condition, threatened with collapse and was partially demolished.

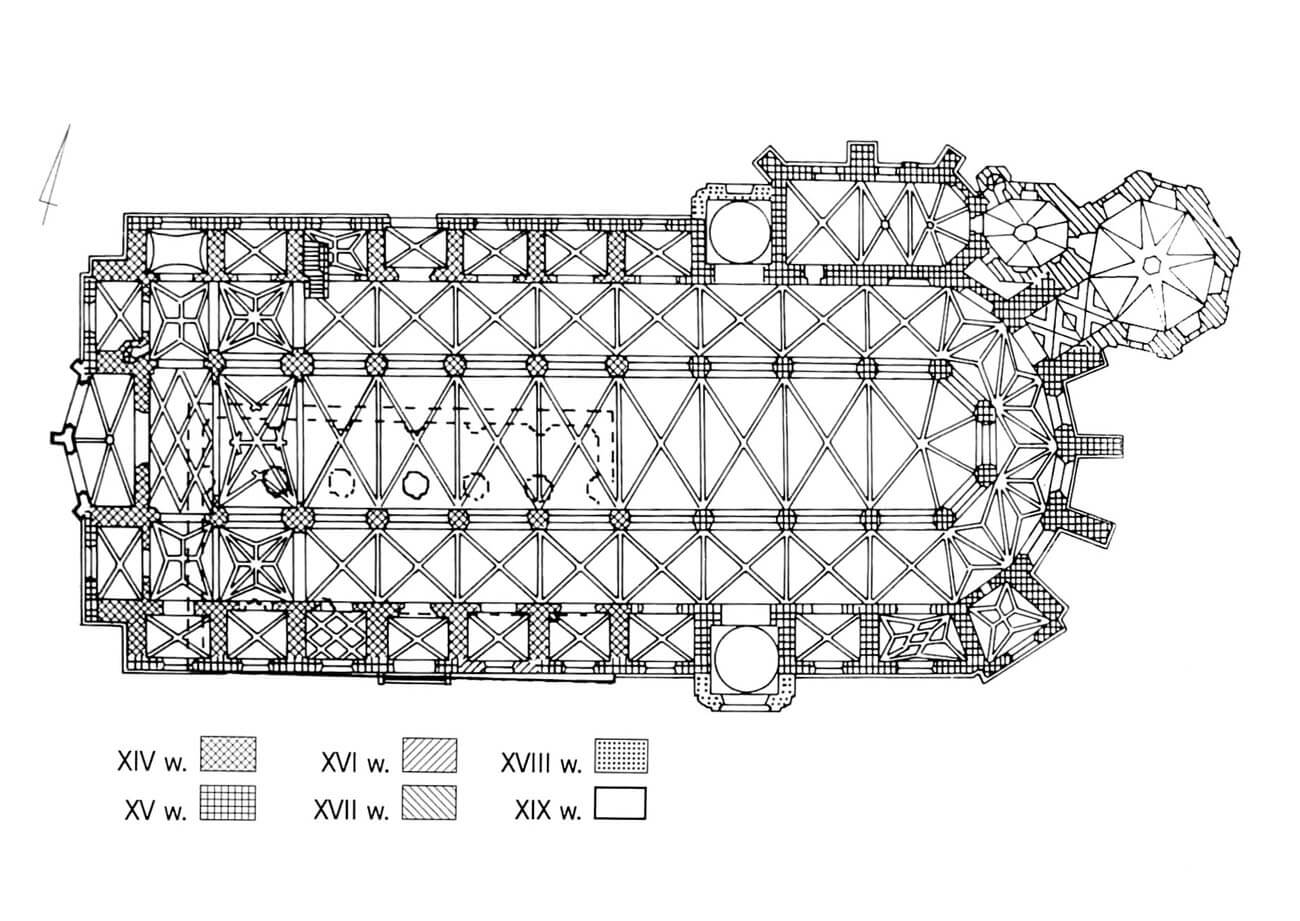

The Gothic church of St. James and St. Agnies was built in two stages over many years. Works began in the 80s of the 14th century on the initiative of Wacław II of Legnica, the bishop of Wrocław, who wanted to erect a representative temple for the Duchy of Nysa. Contrary to early modern records, the eastern part of the church was probably built first, and was covered with a lead roof in 1392. In 1401, this part burned down during the great fire of the town. Preparations for the reconstruction were made in the same year, when the indulgence was granted “ad reparationem parochialis ecclesiae s. Jacobi in Nissa”. In 1416, the roof was rebuilt, this time covered with slate. Perhaps already at that time the foundations for the western part of the church were laid, which had been under construction since 1423, when the town council concluded an extension contract with Peter Frankenstein, a master educated in the Prague workshop of the famous Peter Parler or inspired by the achievements of West Pomerania and Brandenburg. Frankenstein was to receive 190 marks for erecting the choir (“kor”), which most likely referred not to the choir – chancel, but to the music choir, i.e. the western part of the church. The remuneration of the master who erected half of the church could not be lower than the master covering the roof in 1416 (who was paid 280 marks), so the “choir” from the contract of 1424 could not be identical with the chancel. This would be confirmed by another contract for 450 marks, under which the part “from the crucifix to the choir” was to be erected. The works were to be completed in 1430, despite the Hussite invasion of 1426.

In 1474, the bishop of Wrocław, Rudolf von Rudesheim, laid the cornerstone for the construction of a free-standing tower – a belfry, however, as in the case of the church of St. James, the effort of financing the work was taken on by the townspeople of Nysa. Although the floors of the belfry were decorated with the coats of arms of individual bishops, the town council kept accounts, sought and employed architects. The builder Nicholas Hirz, under the supervision of Nicholas Amelung, erected the two lowest storeys, and during the reign of bishop John IV Roth, from 1493, the third storey was being built. The fourth one was founded by Bishop John V Thurzo in 1516. Despite plans to make the tower the tallest in the town, a turbulent period and future disasters meant that construction was completed on this floor.

In 1542, the church was damaged again during another great fire of Nysa, but it was quickly repaired. During the renovation, a new net vault was to be installed in the central nave to replace the collapsed one, but probably the original vault from the 15th century survived the fire and was only renovated at that time. Then, before 1551, a new roof truss was made, in the years 1551-1553 the Italian John Wahel added extensions over the crowning cornice, in 1554 George Stolz from Olomouc covered the roof with slate, and George Behem covered the ridge turret with a sheet. In the 1580s, the organ choir was extended and a staircase was added, funded by bishop Martin Gerstman.

In the first quarter of the 17th century ownership of the church was questioned because of the claims put forward by Protestants. In order to settle the dispute, a census of the parish was organized, which showed a three-man advantage of Catholics over Protestants, thanks to which the church remained a Catholic temple. In the following years of the 17th and 18th centuries a number of early modern chapels were added by Catholics to the church, and the interior was completely changed in the Baroque style. The building suffered serious damages in 1741 during the Silesian Wars. Soon it was renewed, but the temple suffered even greater damage in 1807, during the siege and heavy artillery fire of the city by the Napoleonic army. The reconstruction in the years 1889-1895 was combined with another radical change in the church interior, this time in the neo-Gothic style. Among other things, a new vault in the central nave was built, a western porch was built, the stair tower at the sacristy was raised, and the windows were replaced.

As a result of the war in 1945, the temple has survived the last cataclysm in its history. The roof and two side chapels burned down, the west gable collapsed, stained glass windows ceased to exist, the other side chapels and most of the equipment were also seriously damaged. The reconstruction, during which regothisation was carried out, began shortly after the takeover of Nysa by the Polish state and lasted until 1961.

Architektura

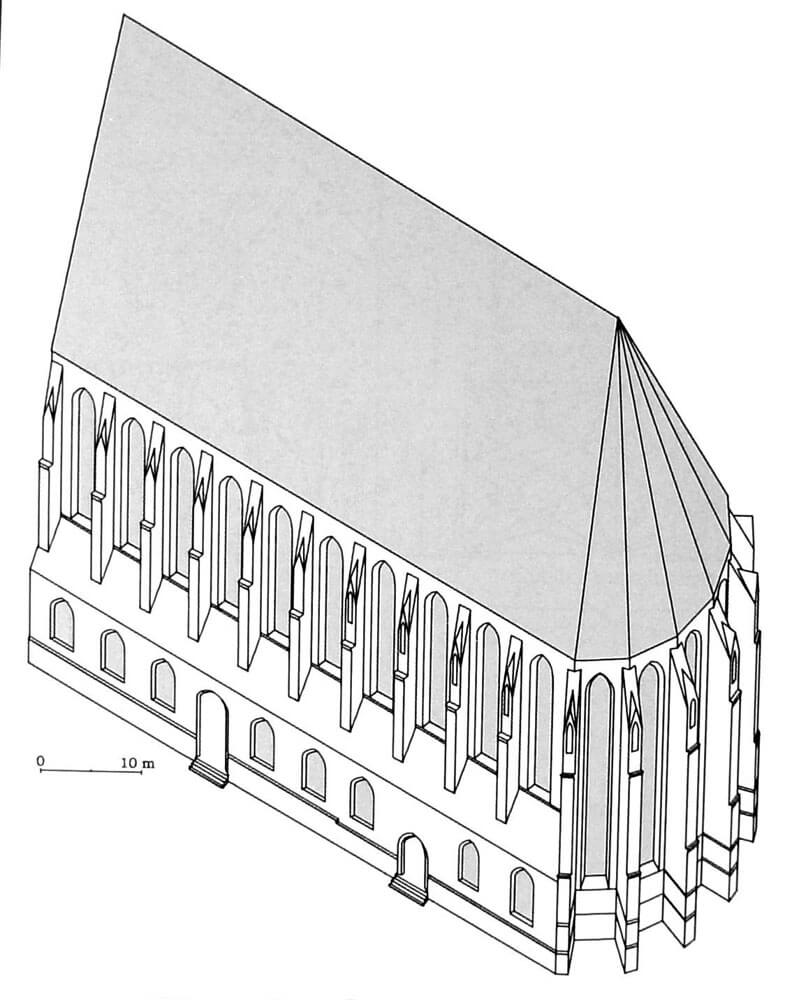

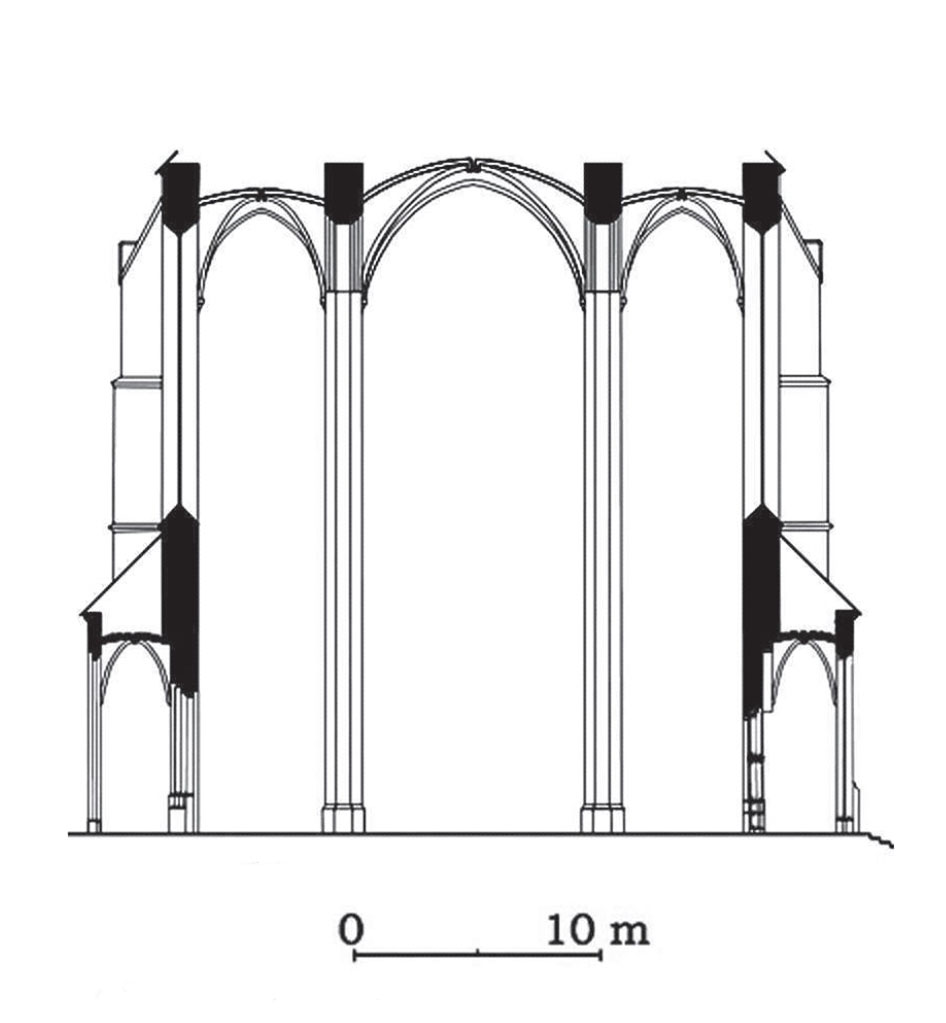

At the end of the Middle Ages Gothic church of St. James and St. Agnes reached the form of a magnificent, nine-bay hall building, orientated towards the cardinal sides of the world, with central nave and two aisles of equal height, without an externally separated chancel, closed with a polygon in the east, with an ambulatory being an extension of the aisles. It was built of light gray sandstone and pink bricks, 59.5 meters long, 22.5 meters wide (including the nave 9.2 meters and the aisles 5-5.2 meters) and a height of 27.2 meters to the vault. The church obtained a compact block of large size. It was covered with a gable roof, one of the steepest in Silesia, thanks to which the total height of the building was close to its length. From the north, a three sides ended sacristy was attached to the chancel.

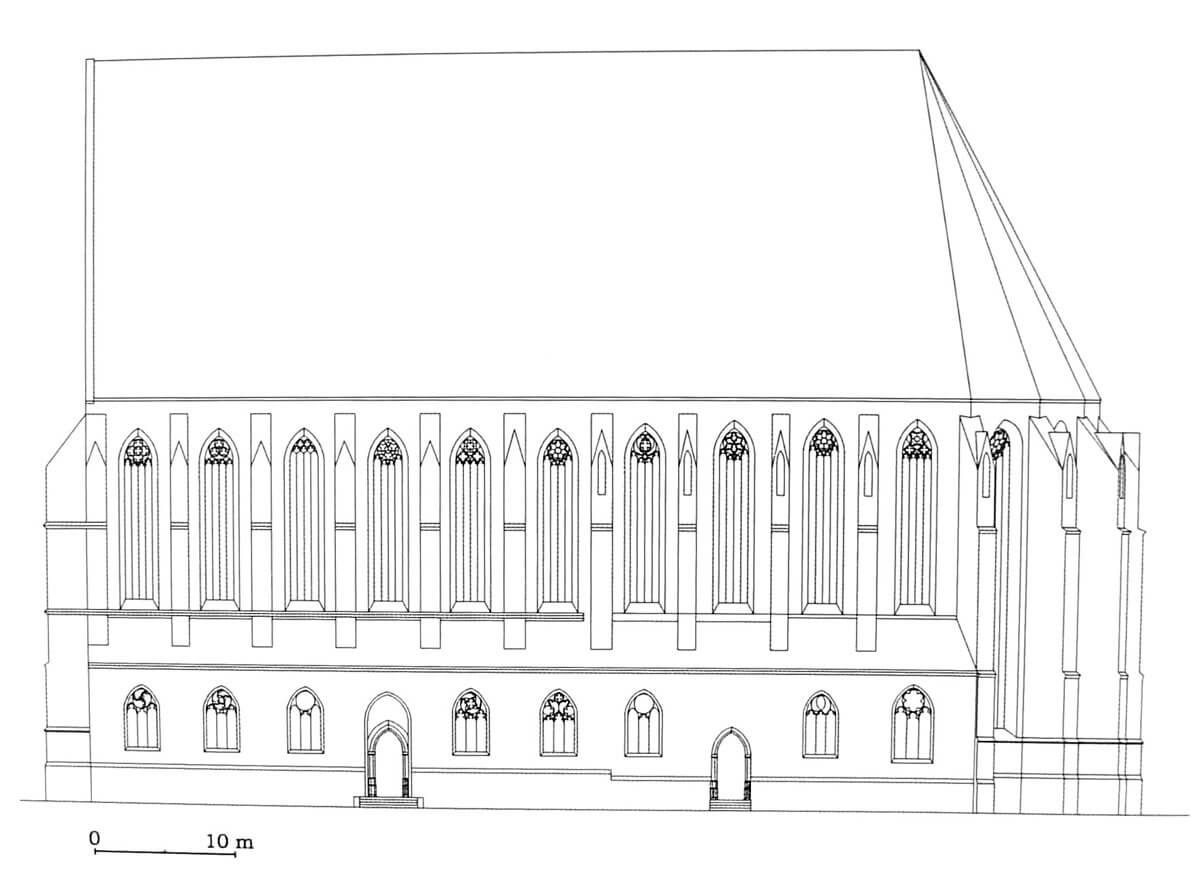

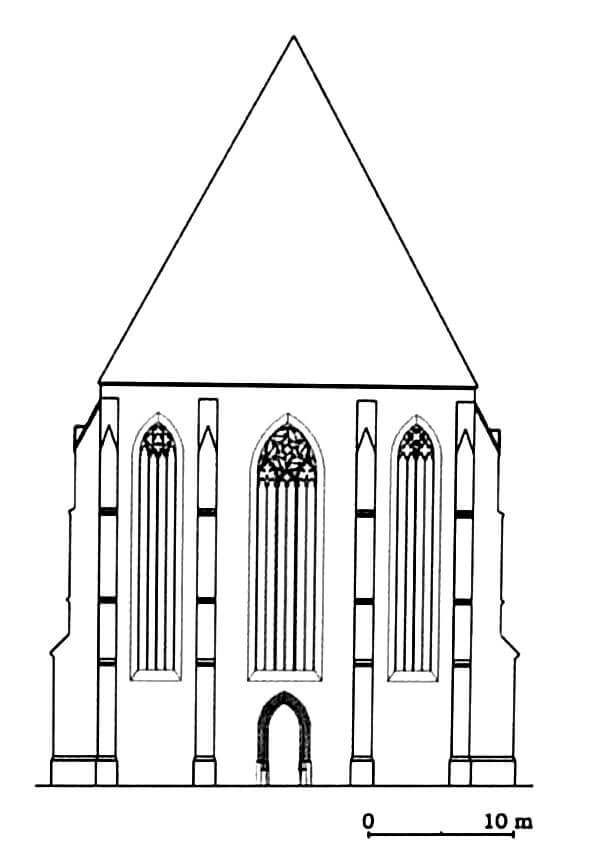

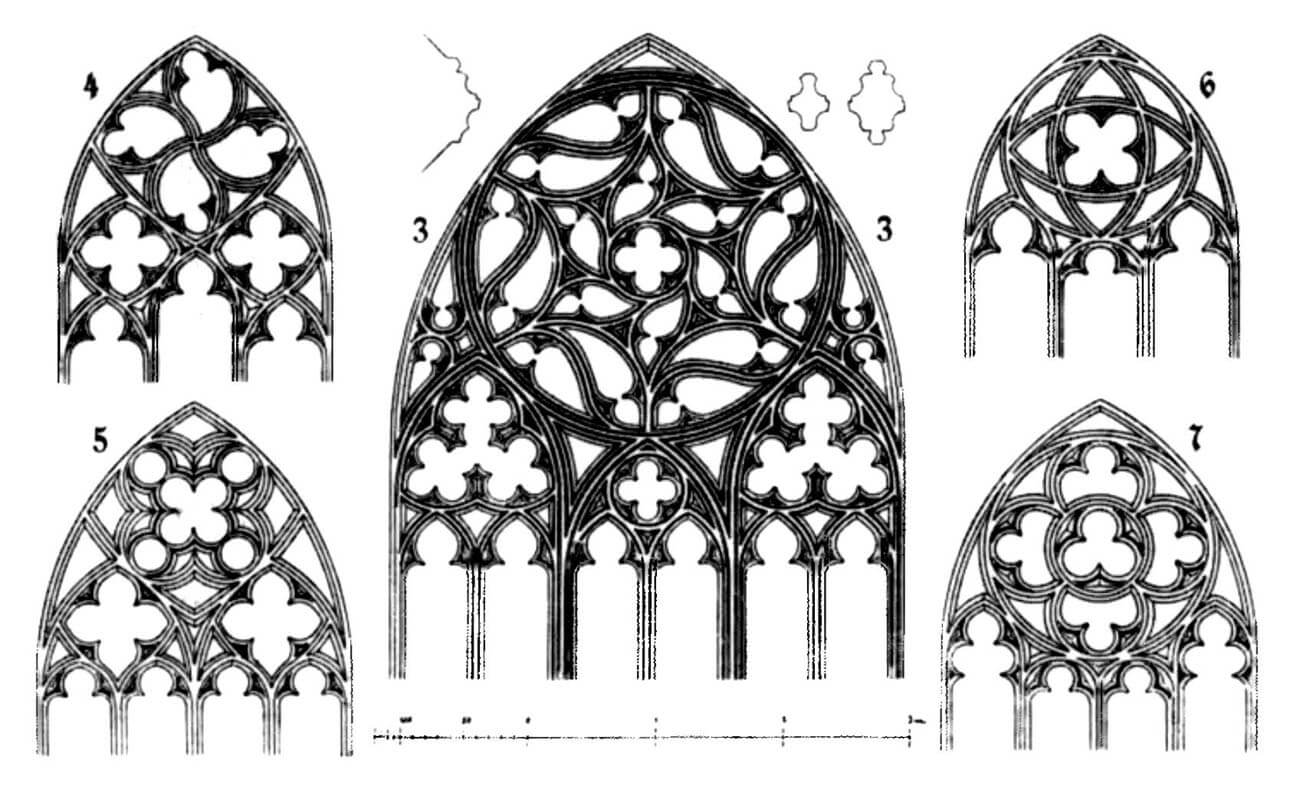

From the outside, the church was surrounded by stepped buttresses, between which from the north and south low chapels were built in the 15th and 16th centuries, as well as porches located in the fourth bay from the west, on the north and south sides. Above the chapels, large ogival windows were pierced with rich tracery in the upper part and moullions dividing the openings into four parts. Deep splayed windows, filling almost the entire space between the buttresses, left only narrow sections of the wall. Their highly vertical zone ended with a horizontal caesura of a cornice under the eaves. On the west side, the nave was extended with two chapels across the width of the aisles. Above them, a gable divided by two buttresses and pilaster strips with ogival blendes was placed. On the border of the sixth bay from the west, the multi-phase construction of the church was revealed. In the eastern part, the buttresses were more decoratively designed (blends in the upper part), stone was used more abundantly in the window jambs (ashlar archivolts, unlike those plastered in the western part), and the windows east of the sixth bay were slightly higher. In addition, the correction of the plan resulted in a plinth fault.

Inside, nine pairs of extremely slender, octagonal pillars were connected by high arcades that, instead of dividing, integrated the internal, uniform space. The pillars were given a characteristic brick form with stone bands evenly dividing their height and with high stone pedestals. In the older eastern part of the church, the pillars were built in the lower parts with the use of narrow, vertically placed fragments of bricks. In the western part, a new bond, more favorable for static reasons, has already been used. The bays of the central nave were rectangular in plan with the longer axis placed transversely to the main axis of the church. On the sides, their counterparts were almost square bays of the aisles. The square form of the latter, instead of the rectangular one, resulted in emphasizing the elongation of the entire church and weakened the separateness of the aisles. At the same time, the pillars no longer constituted divisions between the aisles to such a large extent, but rather, in the optical sense, a forest of buttresses supporting the vault of the entire interior. In the eastern part of the church, the number of sides of the inner and outer polygon of the ambulatory, which did not correspond to each other, caused the buttresses to pass each other (the buttresses were created both on the line of the pillars and between them). The ambulatory divided into alternating bays was gradually narrowed in relation to the aisles.

In the perimeter walls, arcades leading to the chapels were cut out and separated by parts of smooth wall of the windows zone. In the eastern part, the windows originally went down almost to the floor, but later they were bricked up. The aisles, sacristy, most of the chapels and porches were covered with cross-rib vaults, while the ambulatory with nine-part vaults. Above the eastern chapel on the south side, a deformed stellar vault with ribs based on corbels with figures of angels was installed. In the western part of the nave, there was a musical and bourgeois choir, under which there were net and stellar vaults, with the central bay distinguished by the endings of intersecting ribs. From the 15th or the first half of the 16th century, the central nave was covered with a net vault with stone ribs, which blurred the divisions into bays. The ribs descended onto corbels, with a triad of ribs running to each support. Since the pillars, standing quite densely, were created as a rhythmic, but not very differentiated mass, corbels and ribs spiringing formed a distinction in the vault area, showing them as separate units. In the polygon closing the chancel, the network of ribs was complicated into the shape of a star with a boss in the center and arms resting on pillars.

The sacristy of the church, decorated with a rich sculptural decoration, referred to the chapel type. The bosses of its cross ribs were equipped with architectural canopies, the figure of a kneeling angel, the coat of arms of the Duchy of Nysa, and a human heads and a leafy masks were placed on the yoke ribs. The corbels were shaped as leaf masks and human heads. One of them, in the form of a bust of a bearded man, may have depicted the image of an architect. The person of the founder and the main user of the church was indicated by the coat of arms of the Duchy of Nysa placed on the boss of the vault. Above the sacristy, on the upper floor, there was a room, probably opened with wide windows to the chancel, in the form of a bishop’s gallery – an oratory. The successor to this place of honor could be the so-called the “Golden Choir”, built in 1547 between the pillars.

Entrance portals to the church received rather modest forms with moulded and slender jambs. The southern portal was placed on a high, two-level pedestal, and its stepped jambs were equipped with heads with floral decorations. The northern portal was also made of stepped and moulded jambs, but without the heads. Both were placed inside high porches covered with cross vaults, accessible through pointed openings with moulded jambs. Only the saddle portal stood out from the northern aisle to the sacristy, topped with a truncated trefoil, with floral decoration on the lintel and with sheet-metal doors.

Originally, the windows contained multi-colored stained glass, letting in the interior multi-colored light, which intersected with the coloring of the walls and pillars of the church. There, pillars with cinnabar surfaces of non-plastered bricks separated by white joints and strongly accented by white and yellow bands of stones, further intensified color phenomena, unless originally the facades of the walls and pillars were hidden under plaster or whitewash (the stone bands were certainly intended to strengthen the stability of the pillars’ construction). The architect created a building in which, standing in the central nave, the light sources remained virtually invisible, but the entire interior was filled with light. Looking east, one could see two pillars of the ambulatory breaking out of the row of pillars between the aisles, set against the background of the ambulatory windows, whose narrow fragments created the ambient light effect with light and a vague halo around the pillars.

Next to the church, on the north-west side, a free-standing belfry was built, which construction began in 1474. It was erected of bricks, but covered with stone cladding, on a square plan reinforced in the corners with strongly protruding buttresses. The storeys were separated by drip cornices, between which pointed-arched windows were placed, in the lower storey decorated with crockets and lush flowers. The buttresses in the lower part were decorated with delicate blind traceries connected by ogee arches with crockets in the crown. The second storey of the the buttresses was three-side ended at the height of the fault with ogival recesses flanked with decorative columns.

Current state

Only the foundations of the first Romanesque building remain to this day, which can be seen in the basement of the current Gothic church. Perhaps these relics come from two different buildings, because the remains of the two pillars differ significantly from each other. The Gothic church preserved to this day, as well as the nearby belfry, in its turbulent history suffered numerous fires, damages and was subjected to repeated modernization, but its characteristic silhouette remained unchanged to this day. The main early modern and modern transformations that influenced the appearance of the building are the neo-gothic western porch, the reconstructed western gable and a brick cross-rib vault from the late 19th century in the central nave, which, despite the protests of Hans Lutsch, replaced the 15th or 16th-century net vault with stone ribs. Also, most of the window tracery is the result of early modern and modern renovations, although it is difficult to distinguish the original ones from those mentioned. Probably their weathered stonework has been largely replaced, but the geometry of the motifs has not changed. The original main portal has not been preserved in the western façade.

bibliography:

Architektura gotycka w Polsce, red. M.Arszyński, T.Mroczko, Warszawa 1995.

Jarzewicz J., De constructione ecclesiae. O artystycznych i społecznych uwarunkowaniach architektury kościoła św. Jakuba w Nysie, “Artium Quaestiones”, tom VIII, 1997.

Kębłowski J., Nysa, Warszawa 1972.

Kozaczewska-Golasz H., Halowe kościoły z XIV wieku na Śląsku, Wrocław 2013.

Kozaczewska-Golasz H., Halowe kościoły z wieku XV i pierwszej połowy XVI na Śląsku, Wrocław 2018.

Pilch J., Leksykon zabytków architektury Górnego Śląska, Warszawa 2008.

Walczak M., Kościoły gotyckie w Polsce, Kraków 2015.