History

The Cistercians came to Lesser Poland (Małopolska) around 1220 from the abbey in Lubiąż in Lower Silesia on the initiative of Wisław from the Odrowąż family. They were initially settled in Prandocin and later in Kacice, but after two years the bishop of Kraków, Iwon Odrowąż transferred them to the Mogiła near Kraków. It can be assumed with high probability that the decision was influenced by disputes in the Odrowąż family and the functioning of an older pagan ritual site connected with the Wanda Mound, the alleged grave of the tribal ruler.

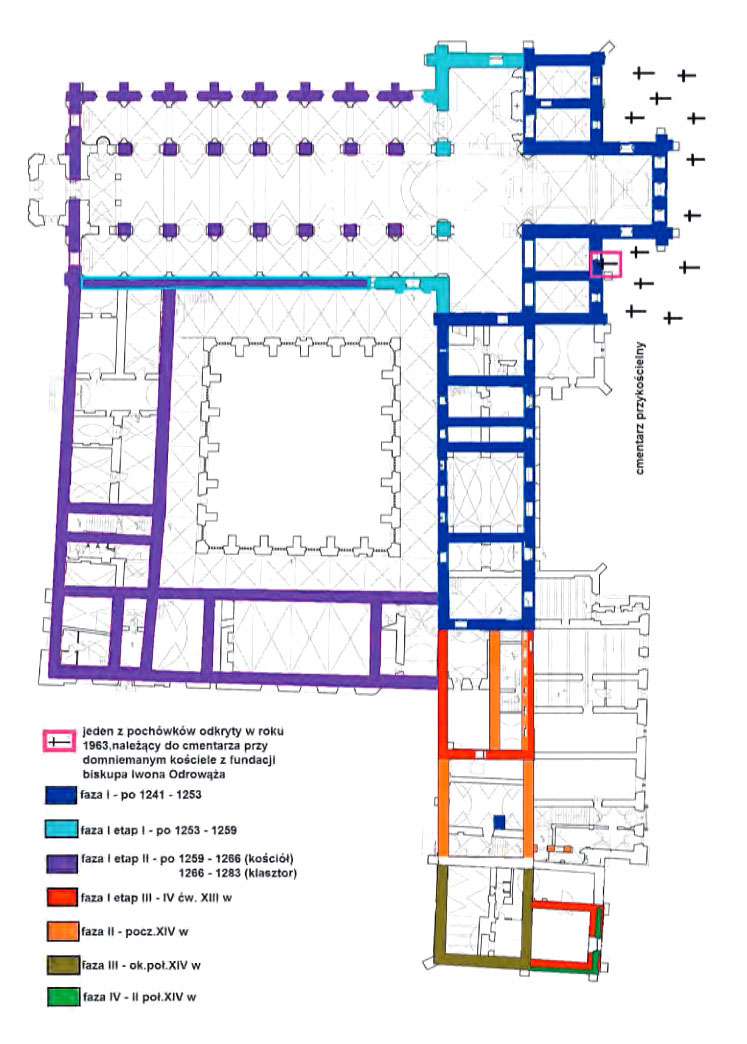

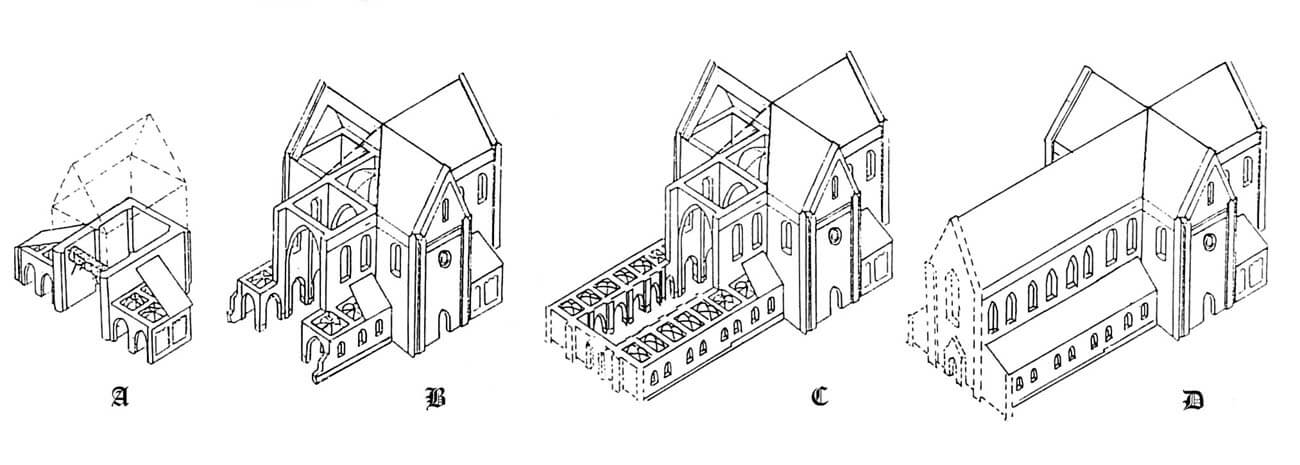

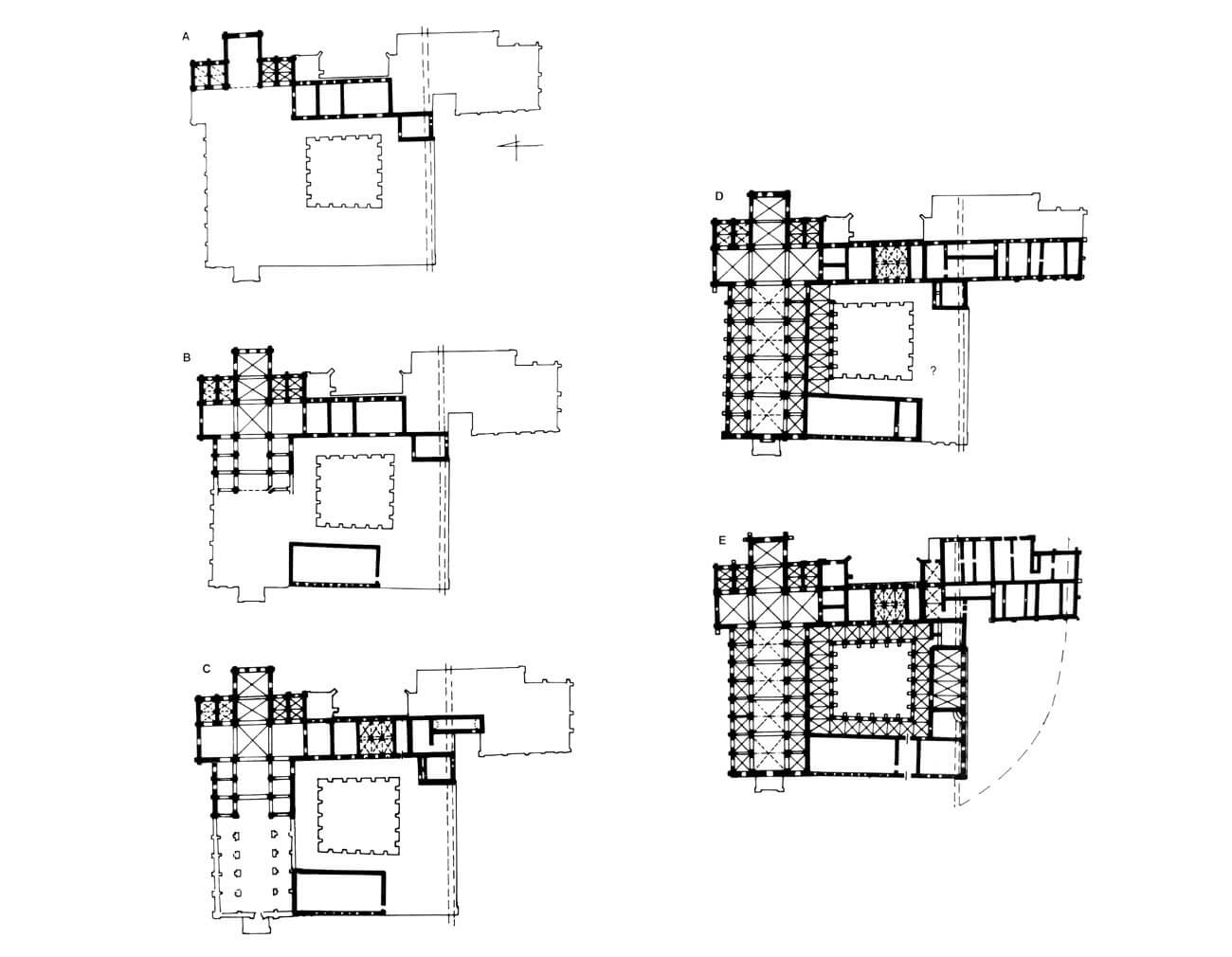

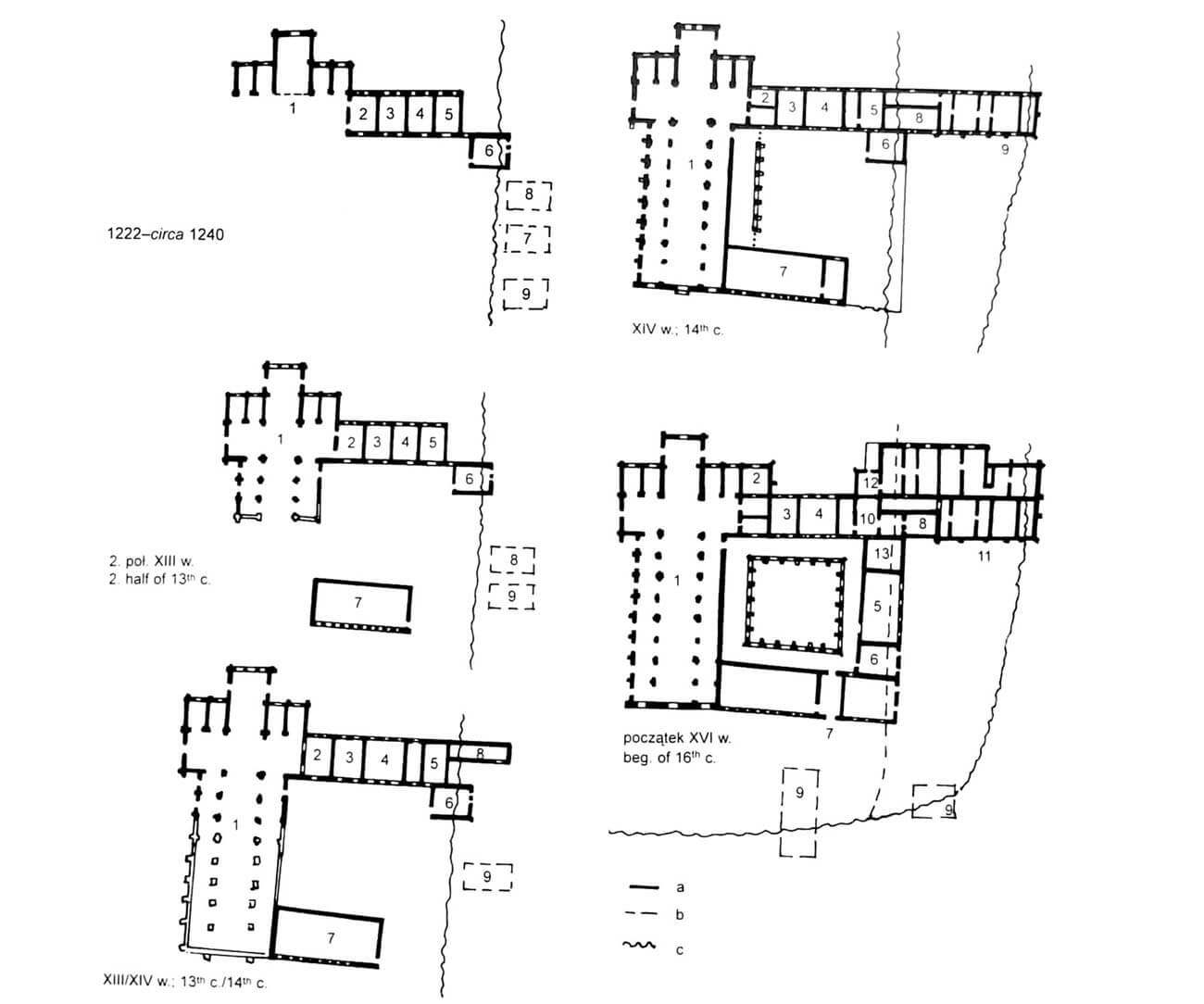

Construction works on the monastery church began probably in 1222, with the building of the chancel and side chapels from the eastern part of the church. Already in 1225, when the Cistercian community arrived in Mogiła, the first consecration took place, probably related to the completion of one of the chapels. The works were continued at a rapid pace until the death of the founder Iwon in 1229. Soon after, a conflict broke out between the abbey and the Odrowąż family, which may have contributed to the partial disbanding of the construction workshop. In the following years, construction continued, but at a slower pace and with a significant reduction in sculptural decorations.

The construction of the church and monastery was again interrupted during the reign of Abbot Henry in 1241 when Mogiła was ravaged by the Mongol invasion. To obtain funds for the reconstruction in 1253, Pope Innocent IV gave an indulgence, but in 1260 there was another invasion of Asian nomads. The church, not yet fully completed, was again consecrated by the Bishop of Kraków, Jan Prandota, in the presence of Prince Bolesław the Chaste in 1266.

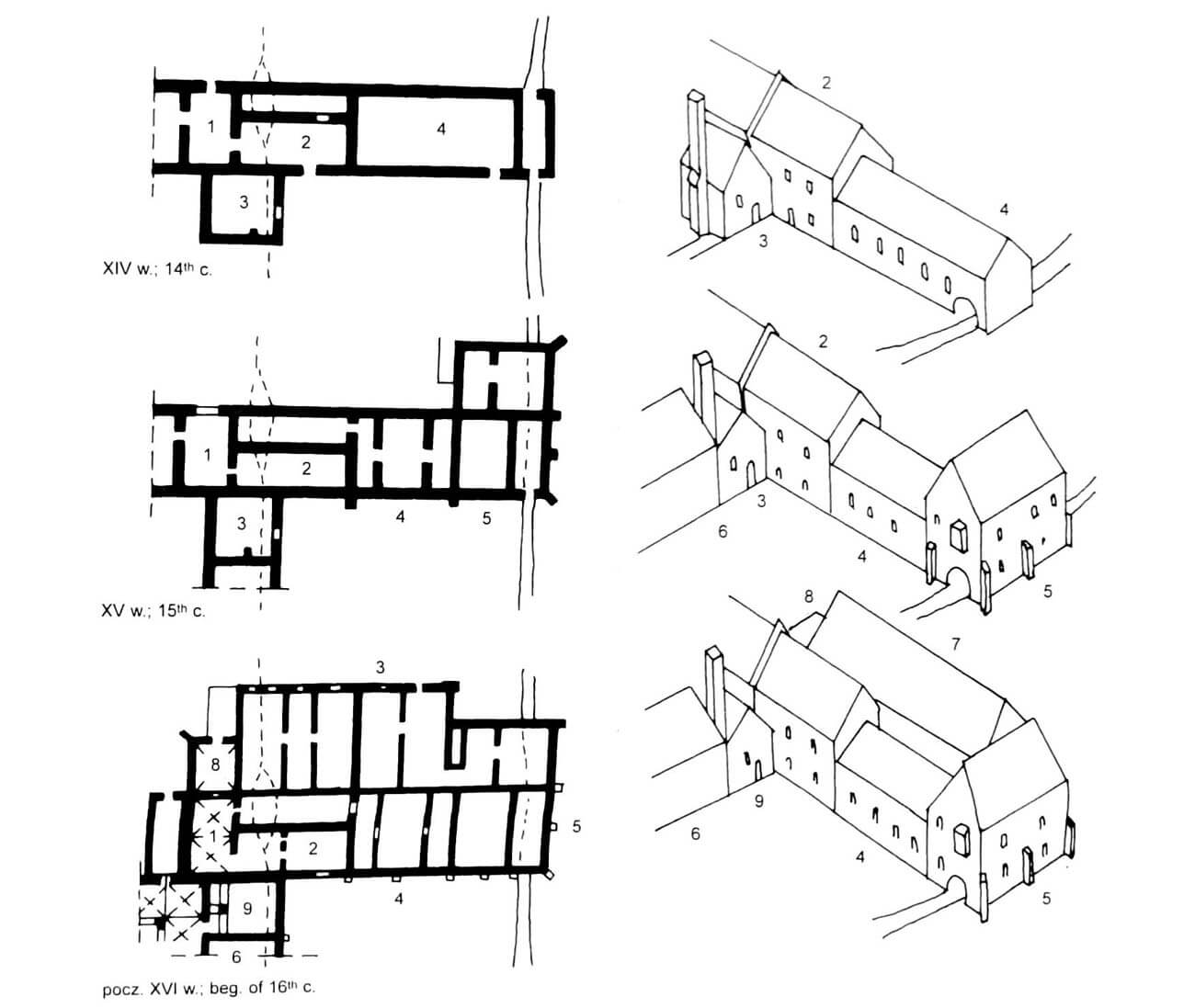

The next stage of the thirteenth-century development of the abbey took place in the years 1266–1283, when the construction of the most important monastery buildings was completed. It was then that the most significant expansion of the monastery by the western and perhaps southern wings was to be carried out by Abbot Herman, who “greatly expanded the monastery and made it more useful for the entire congregation.” Even at the end of the 13th century and at the beginning of the 14th century, construction work was most likely on the nave and the vaults of its aisles. During the reign of King Casimir the Great, the sounds of building works could still be heard in the monastery. At that time, the walls of the three western bays of the church were raised and the nave was vaulted. Later, the church was renovated and rebuilt several times, thus becoming a unique mixture of Romanesque and Gothic styles.

In the first half of the fifteenth century, the building was destroyed twice: by an earthquake around 1444 and a fire in 1447. After the second fire in 1473, the abbot Marcin Matyspanek proceeded to the general rebuilding of the entire abbey, during which, among others, the church was strengthened with buttresses. In 1505, due to the threat of collapse, new vaults of the central nave were made, and in 1538 during the reign of Abbot Erazm Ciołek, one of the brothers, Stanisław Samostrzelnik, decorated the church and monastery with paintings (presbytery, chapels, transept, library). At the time of Erazm Ciołek, there was also a painting and illuminating school in the monastery, whose most famous representative was Samostrzelnik. After the middle of the 16th century, another fire destroyed the church again. The rebuilding and extension of the abbey lasted during the rule of Abbot Białobrzeski in 1559-1586 and Goślicki in 1586-1601. In the first half of the 17th century, a school of philosophy for the monastery youth was founded in Mogiła.

Mogiła was often visited by the rulers: Queen Bona, Sigismund I the Old, Sigismund II Augustus, Stephen Báthory, and Sigismund III Vasa. In 1655, the abbey was occupied by the Swedes. Several monks were killed and the treasury was looted, what is more, after the withdrawal of the army, the abbey was additionally robbed by local peasants. In 1657, the allied Austrian army captured the ruined monastery, where King John II Casimir Vasa lived with his wife Marie Louise Gonzaga. The rebuilding was carried out around 1670 under Abbot Denhof. In 1708, a theological college was founded in Mogiła, the so-called General Study with the right to confer academic degrees. Unfortunately, subsequent fires damaged the monastery church in such a way that in 1712 the vault of the central nave collapsed, and in 1748 the ridge turret, which fell and destroyed the vault of the aisle. In the second half of the 18th century, renovations were carried out many times. During the time of the Polish captivity and partitions, the monastery did not dissolve like other Cistercian monasteries, because it lay within the so-called Free Town of Cracow. During the Nazi occupation, the monastery was occupied by the Germans and the monks scattered. In 1946-48, the monastery church was restored, partially restoring its original appearance.

Architecture

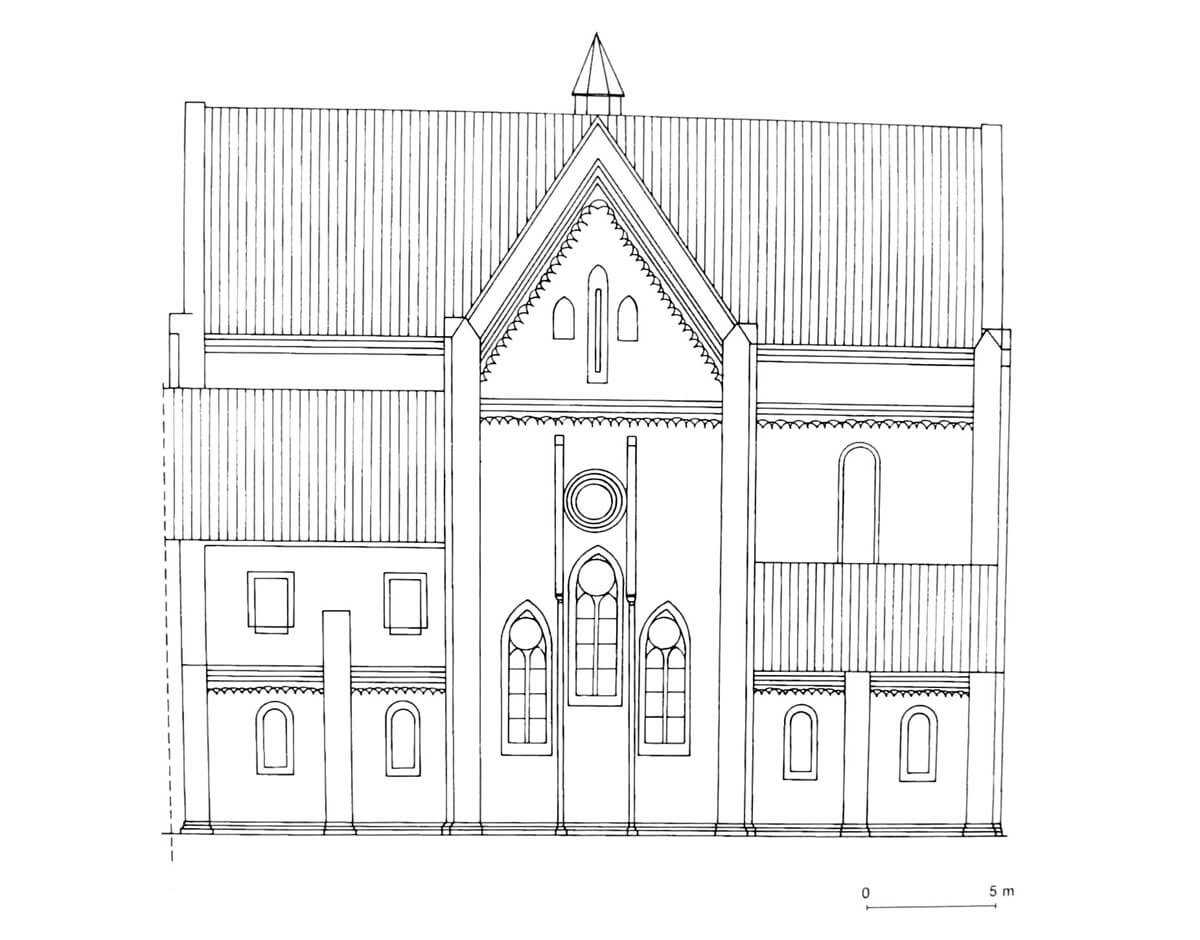

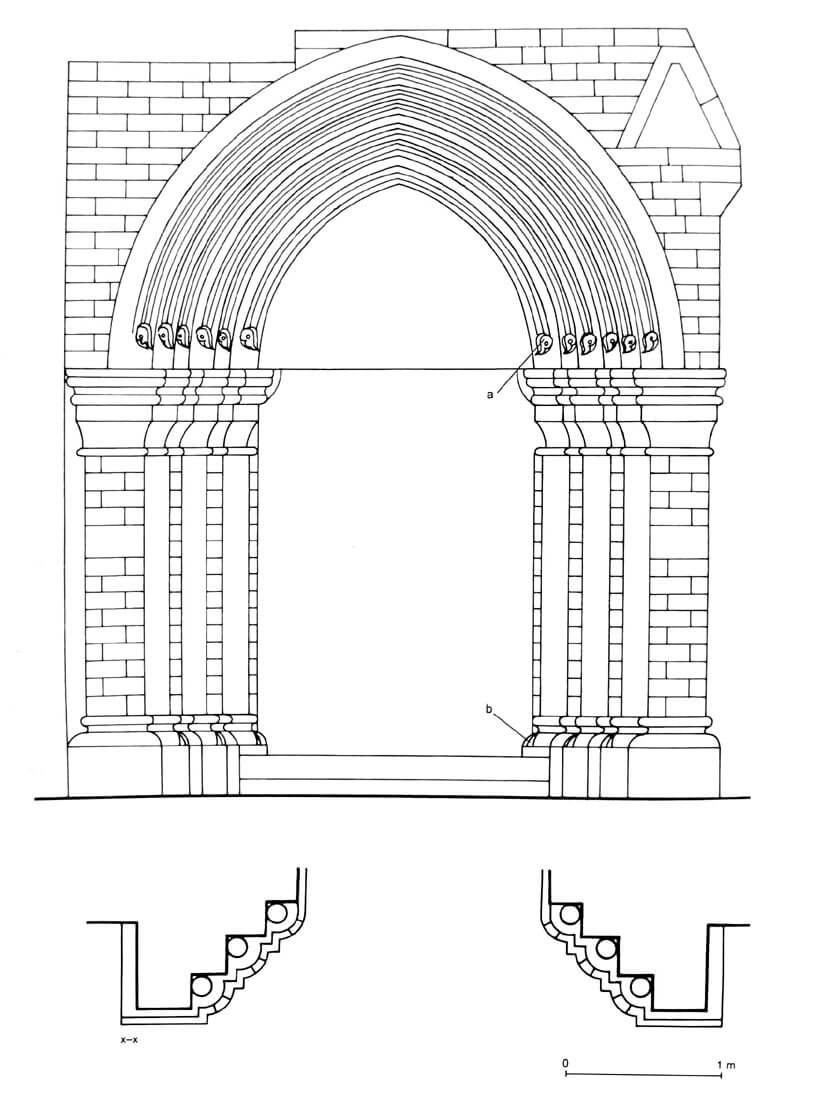

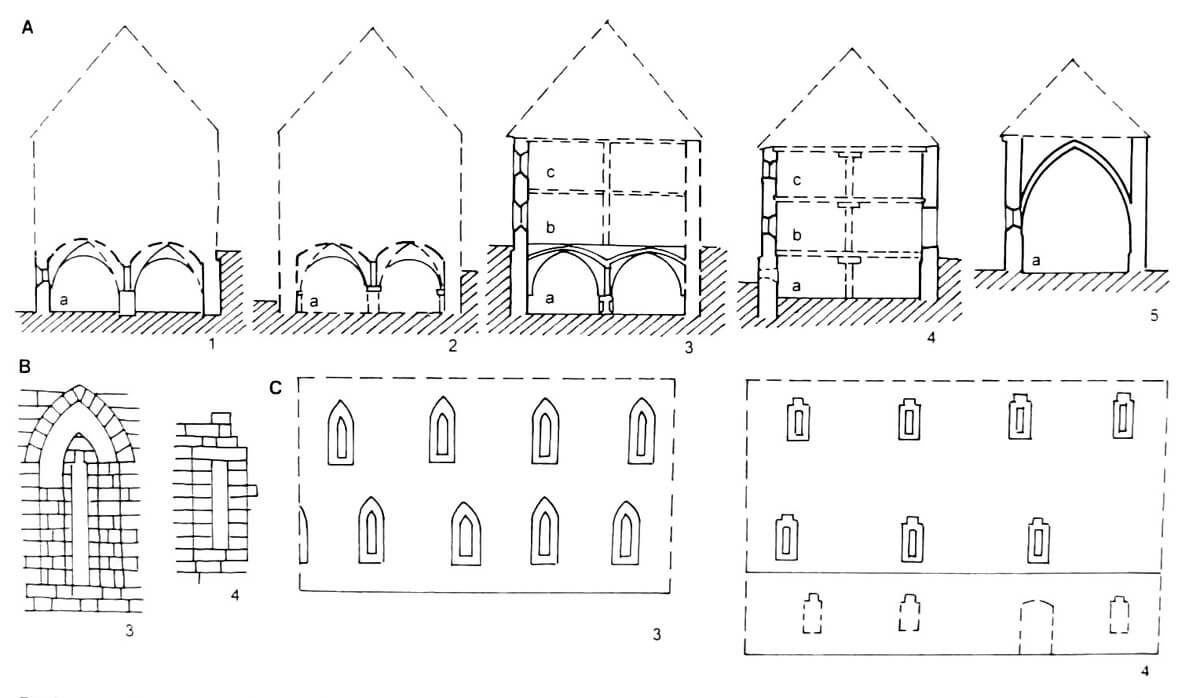

The church was built of bricks with the use of sandstone for architectural and decorative details such as wall shafts, ribs, bosses, pilasters and cornices. It received the form of a basilica 63.5 meters long, on the Latin cross plan, with a three-aisle, eight-bay nave 19.7 meters wide, transept 27 meters wide and a two-bay chancel flanked by two chapels from the north and two from the south (similar to Jędrzejów, and unlike Wąchock, Koprzywnica and Sulejów abbeys). The church, according to the Cistercian rule prohibiting the sumptuous and monumental buildings, did not receive the tower, but only a small ridge turret at the intersection of naves.

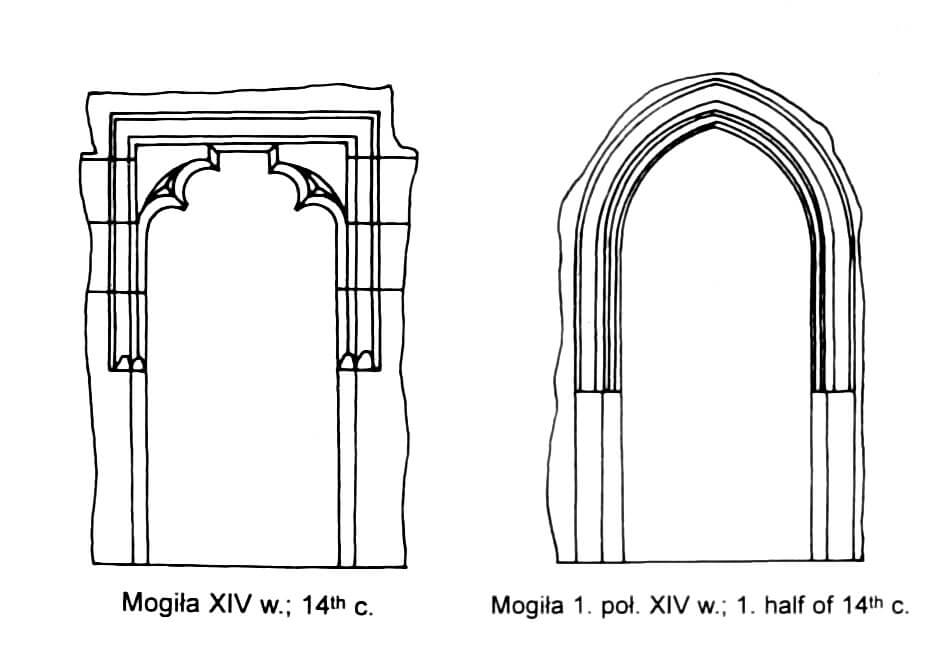

The facade of the church was divided by buttresses in the corners and on the bays dividing lines. Friezes were created at the height of the original culmination and at the gables. In the chancel and transept it obtained the form of semi-circular interpenetrating arcades placed on a bright plastered background. The eastern facade of the chancel was distinguished by three large, pointed windows with tracery, the ocular with a moulded frame situated above and a triangular gable. The wall of the chancel was also divided into three vertical parts with stone columns with chalice and cube capitals, which support further running pilaster strips. The oldest windows in the longitudinal walls of the nave (two eastern bays) and the chancel were originally relatively narrow, splayed, topped with semicircular arches. Later windows in the western bays of the nave received Gothic, pointed forms.

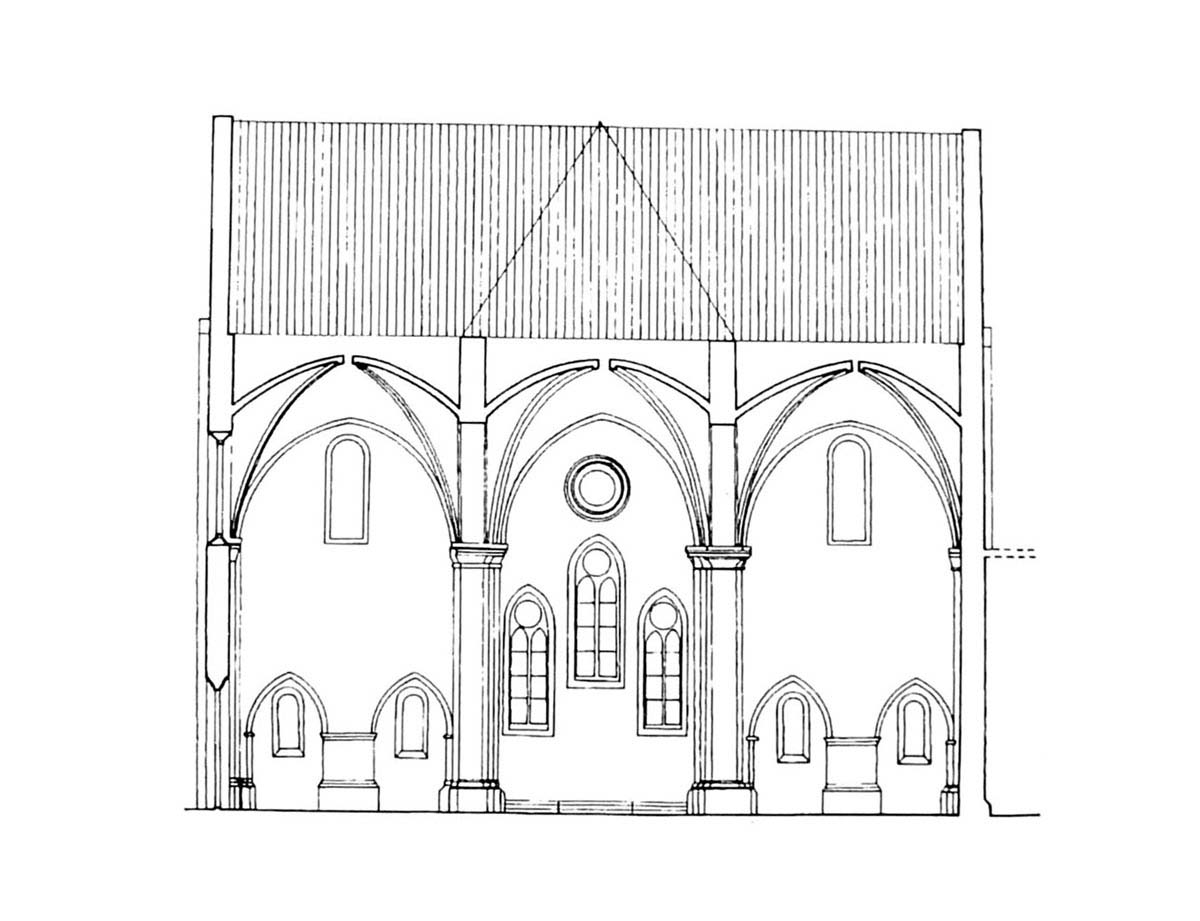

The interior of the church was covered with rib vaults, based in the eastern part and in the aisles on columns with cup and cube heads, as well as bases with a flattened moulding and plain crockets. Only in the chapels the heads were covered with bas-relief decoration with floral motifs. The bays were separated by arch bands, which, similarly to the wall ribs, were made of bricks, while the remaining diagonal ribs were made of stone and brick fittings, arranged alternately. The central nave was separated from the transept by a arch supported on a moulded stone and brick bracket. The church floor was made of ceramic tiles with rectangular and square shapes. They all had an embossed palmette and braid ornament with various patterns. The tiles were covered with yellow – green, yellow, brown and white – yellow glaze.

In the late Gothic period, the walls of the church were raised about 1.6 meters above the arcaded frieze. For this reason, the original cross-rib vaults in the interior were replaced in the central nave and in the four eastern bays of the northern aisle with barrel vaults. The vaults of the northern pair of chapels at the transept also changed in a similar way.

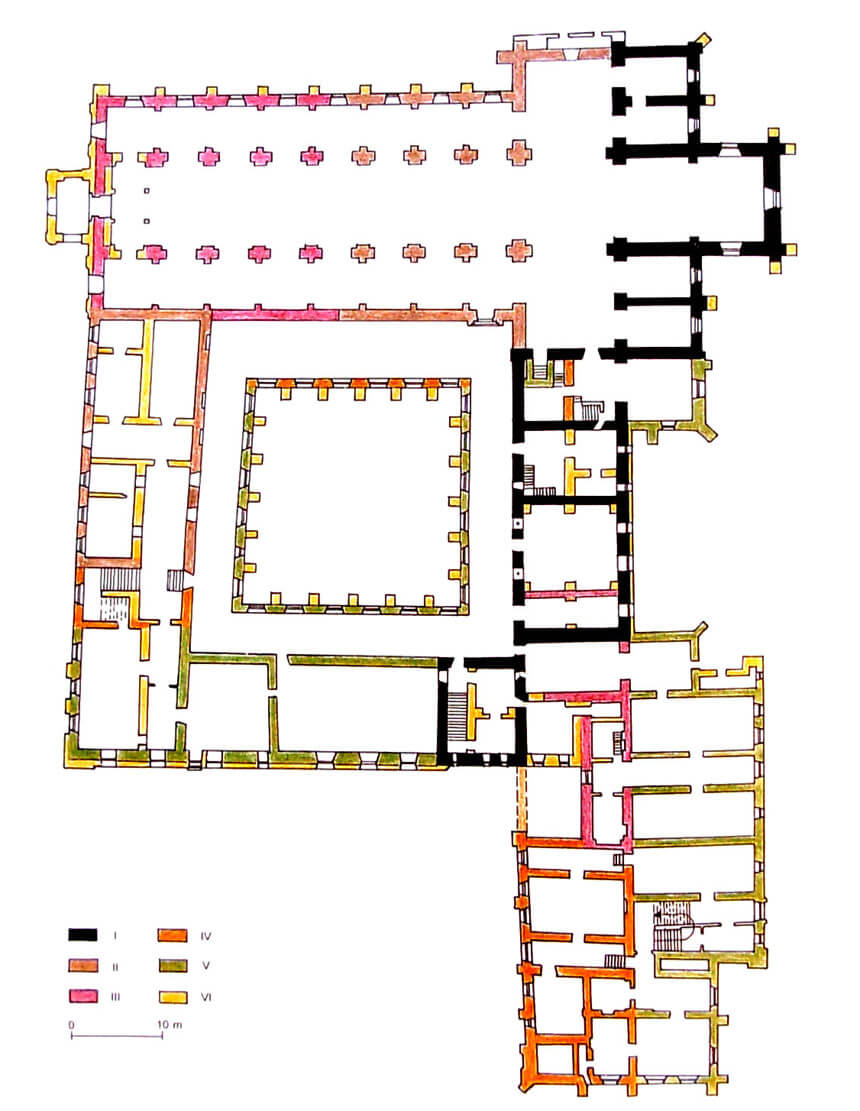

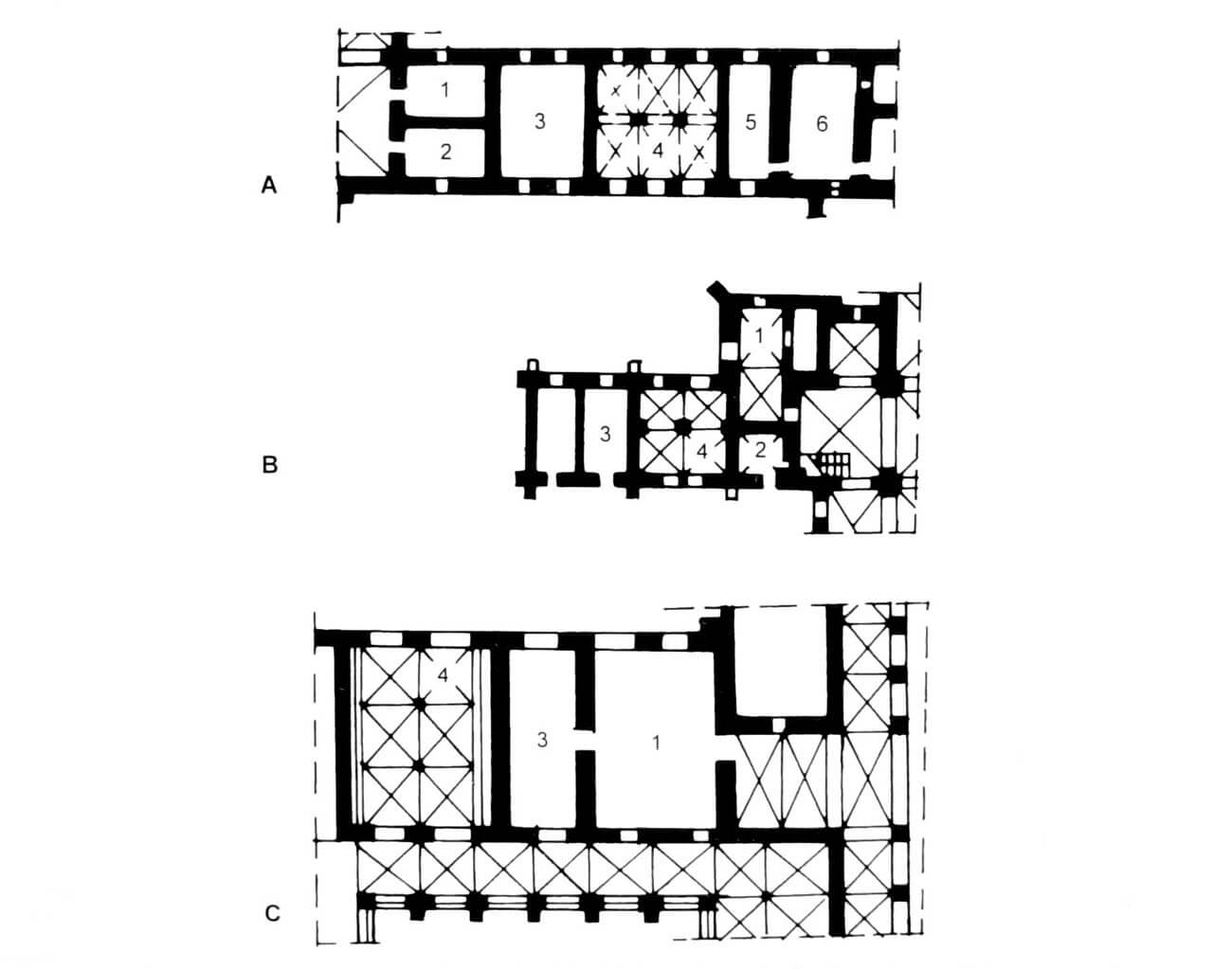

The monastery buildings were erected on the south side of the church. At the end of the Middle Ages they consisted of three wings, which cloisters surrounded the internal patio. In the light of the latest research, the eastern wing from the first half of the 13th century can be considered the oldest. From the north, it housed the sacristy adjacent to the church, as a result of expansion at the end of the Middle Ages consisting of three rooms. Then there was a parlour, that is a room where the brothers could talk without breaking the vow of silence. On the southern side, the parlour was adjacent to the chapter house, the most important room in the abbey, used for the daily gatherings of monks under the leadership of the abbot, during which the most important matters of the community were consulted and the monks’ vices were judged. The entrance to the chapter house led from the cloister, the adjacent wall was also pierced with two two-lights windows, so that lay brothers gathered in the cloister could listen to the proceedings. The next room of the east wing was a lobby that allowed to go outside the enclosure buildings and the refectory, later transformed into a fraternity, that is a room for manual work of monks, used especially in winter. Most often scriptorias were arranged in fraternities, located as close to the calefactories as possible, so that the brothers could warm their fingers frozen in winter while writing the books.

On the first floor of the east wing there was a dormitory of th emonks, connected by stairs with the church transept, so that the brothers could quickly get to night prayers. On the opposite side from the dormitory, one could get to the latrines, from which the impurities fell into the system of canals supplying water, and then getting rid of it after cleaning the latrines. There were two canals in this part: one served the ground floor of the building, the other was connected to the first floor. In the fourteenth century, at the southern end of the east wing, an impressive one-story building was erected with small windows ending in segmental arches. It probably performed economic functions at that time.

The south and west wings were built later, because in the second half of the 13th century and in the 14th century. The earliest room of the southern wing was the kitchen, located on the site previously used by production ovens. Its interior was illuminated by a slit window in the eastern wall, and a small, round ventilation hole was placed in the upper part of the western wall. In the middle of the kitchen was a water canal by the south wall. At the end of the 15th or the beginning of the 16th century, the kitchen was turned into a calefactory – a room heated throughout the winter. A new kitchen was erected than in the western part of the south wing and bordered the centrally located refectory. The latter was a four-bay room with a vault which ribs flowed directly into the floor, without the use of corbels.

The west wing housed a cellar at the basement level, rooms for lay brothers, that is their refectory and fraternity at the ground floor, and dormitory on the top floor. The aboveground part was illuminated by small slit windows to maintain a tolerable temperature inside unheated rooms. At first, the dormitories were divided by low partitions between mattresses, and later by timber walls separating individual sleeping cells. As a result of the development, the west wing was extended to the south, and the new room created there was separated from the older one in the north by a lobby connected to the cloister.

All wings were connected by a cloister, covered with a cross-rib vault, supported on corbels. In the northern, the older part, the bays of the cloister received a rectangular form, while in the others, younger parts a square one. At the north side the corbels were hung much higher than on the east, west and south side. The cloisters surrounded an inner patio, a place of rest and contemplation, as well as a garden in which monastery herbs and vegetables were planted and grown.

On the south-eastern side of the abbey at the end of the 15th century and at the beginning of the 16th century, the east wing was extended to the south, where extensive, two-aisle building of the priorate was built (abbot’s house). It received then the upper floor, the eastern aisle, new window openings in the lower part of the western aisle and probably a bay latrine over the new branch of the canal. As the older economic building was converted into the abbot’s house, on the west side of the monastery, two magnificent auxiliary buildings were built over the canal. The library walls above the southern chapels of the church were also built during this period. Its interior was covered with a late Gothic net vault.

Current state

In the architecture of the monastery church, the early Gothic style prevails, retaining numerous Romanesque elements, with the transition between these two medieval styles occurred smoothly during construction. Unfortunately, the facade of the church, a large part of the north facade and the interior of the central nave acquired an early modern character in the 18th century, although many medieval elements were excavated from under the plasters during the restoration works. The windows in their original form have survived in the side walls of the chancel and the round rosette in the eastern wall, under which a triad of Gothic windows is visible. In the southern façade, the original windows of the transept, chapels and two nave windows are original, partially bricked up, while the rest, unfortunately, have been widened. A full system of vault supports has survived in the aisles. In addition to the half-columns and shafts in aisles, chancel, chapels and transept, you can also find piscinas in the southern chapels. The chancel, transept and chapels are covered with polychromes from the 16th century made by Stanisław Samostrzelnik. Significant transformations also affected the enclosure buildings, although during the renovation fragments of the facades with original windows in the west wing or the bay latrine at the abbot’s house were revealed.

bibliography:

Bober M., Architektura przedromańska i romańska w Krakowie. Badania i interpretacje, Rzeszów 2008.

Bojęś-Białasik A., Niemiec D., Opactwa w Lubiążu, Trzebnicy i Mogile a początki cysterskiej architektury ceglanej na Śląsku i w Małopolsce w kontekście filiacyjnych zależności warsztatowych [w:] Architektura sakralna w początkach państwa polskiego (X-XIII wiek), Gniezno 2016.

Grzybkowski A., Gotycka architektura murowana w Polsce, Warszawa 2016.

Jarzewicz J., Kościoły romańskie w Polsce, Kraków 2014.

Krasnowolski B., Leksykon zabytków architektury Małopolski, Warszawa 2013.

Łużyniecka E., Architektura klasztorów cysterskich, Wrocław 2002.

Szyma M., Chronologia budowy kościoła cystersów w Mogile – problem otwarty [w:] Ingenio et humilitate. Studia z dziejów zakonu cystersów i Kościoła na ziemiach polskich, red. A.M.Wyrwa, Poznań-Katowice-Wąchock 2007.

Świechowski Z., Architektura romańska w Polsce, Warszawa 2000.