History

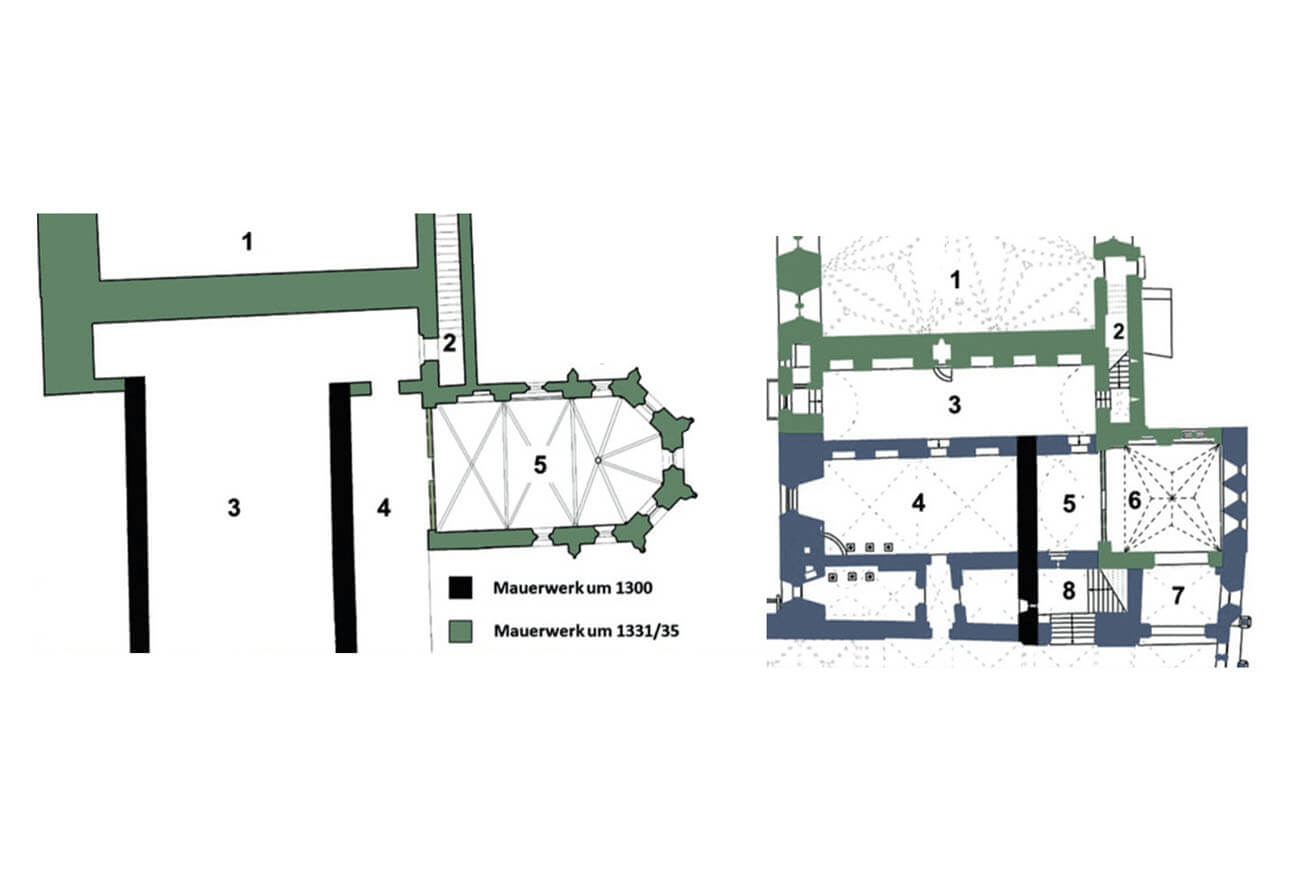

The castle complex in Malbork (Marienburg) was built through gradual expansion, during which the fortifications and buildings were modernized over a very long time. The Land Master Diertich Gatrislebe and the commander of Dzierzgoń, Hermann von Schoennberg, later the commander of the Chełmno land, were probably the initiators of the construction. The castle began to be built around 1280, although preparations in the form of clearing the forest and collecting building materials began two years earlier. First, the brick northern wing of the upper ward was built, then the western and southern wings. A dansker (latrine tower) protruding from the western corner of the castle was also built. These works were completed around 1300, but already in 1280 the seat of the commander of Zantyr was moved to Malbork, then called “Mergenburk”, and in 1284 a document was issued in the castle by the commander of Malbork, Heinrich von Wilnowe.

In 1309, a decision was made to officially move the seat of the Grand Master of the Teutonic Knights from Venice to Malbork, as a result of which the castle became the capital of the Teutonic Knights State. A large number of brothers arrived with Grand Master Siegfried von Feuchtwangen, which required the rebuilding and expansion of the “castrum Mergenburk”. Among other things, the southern wing was completed, the eastern wing with the main tower was built, and after 1331, on the initiative of Grand Master Luther von Braunschweig, the northern wing and the castle church of the Blessed Virgin Mary were significantly enlarged, under which the chapel of St. Anna was built. In a niche on the eastern church facade there was a huge statue of the Virgin Mary and Child, made of artificial stone and covered with a mosaic from Venice in the 14th century. It became the symbol of the main castle of the Teutonic Knights, on which former outer bailey, later the middle ward, by 1333 the first residence of the Grand Masters was erected. This palace became the most representative part of the stronghold, adjacent to the wings of the middle ward, built since the 1320s, while the lower ward became the main craft center for the entire Teutonic Knights state. The order to expand the lower ward and the bridge over the Nogat was given by Grand Master Dietrich von Altenburg in the years 1335-1341. He was also the first Grand Master of the Teutonic Knights buried in the castle St. Anna’s chapel. Under his successor, Ludolf König von Wattzau, according to the inscription on the chapel wall, the reconstruction of the northern wing of the upper ward was to be completed in 1344.

From the mid-14th century until the beginning of the 15th century, knights from all over Europe came to Marienburg to participate in the raids organized by the Teutonic Knights, i.e. armed expeditions to Lithuania and Samogitia, as well as to the tournaments and feasts that accompanied them. The order’s official apparatus was also growing, and its representatives wanted more luxurious living quarters. Therefore, construction works in the castle in the second half of the 14th century were still carried out with greater or lesser intensity, especially in the middle and lower wards. This was evidenced, among other things, by the indulgence document from 1358 for the construction of the chapel of St. Laurentius in the lower ward and a record from 1398 about the completion of the construction of the treasurer’s chambers in the middle ward. In the years around 1380-1396, the Palace of the Grand Masters was thoroughly rebuilt in the middle ward, which became one of the most impressive buildings of medieval secular Gothic architecture. As the decision of expand must have been made several years earlier, probably in the 1370s, its initiator could have been the Grand Master Winrich von Kniprode. In 1399, documents recorded the removal of rubble after construction, although this probably referred to the Teutonic court in nearby Widowo, not to the castle itself.

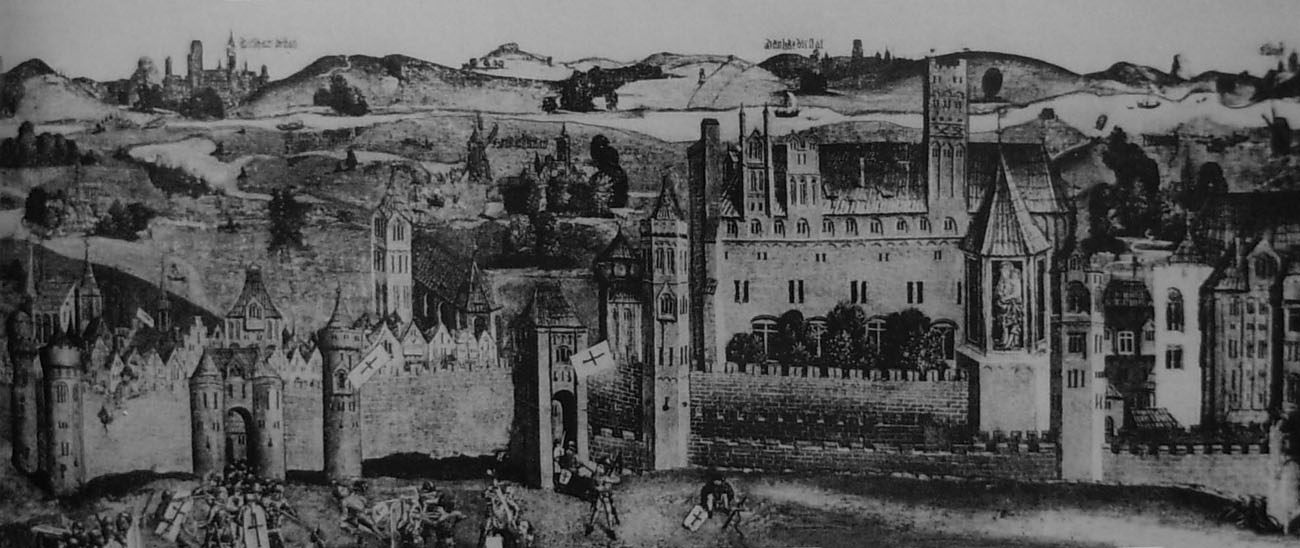

In 1410, after the great defeat of the Teutonic Knights at Grunwald, the commander of Świecie, Heinrich von Plauen, who did not participate in the battle, came to Malbork to organize a hasty defense. Soon, the castle and the town were besieged by Polish-Lithuanian troops led by King Władysław Jagiełło. However, almost two months of attempts to capture the fortress turned out to be ineffective, despite cannon fire from the captured town and the parish church, digging under fortifications, assaults, and the reinforcements from the Old Town of Elbląg (the Teutonic Order however received the help of about 400 sailors from Gdańsk). Marienburg remained uncaptured, but it probably suffered heavy damages, especially in the western wing of the upper ward. In the years 1411-1414, repair works were recorded on the bridge on the Nogat and at the Sparrow Tower, and new fortifications were built on the eastern side of the castle. Then, in 1418, under the supervision of master Niclus Fellensteyn, the New Gate was built, and in the years 1441-1449 firearms-adapted the so-called Plauen’s Ramparts.

The castle was besieged once again in 1454, at the outbreak of the Thirteen Years’ Polish-Teutonic War. Initial attempts to capture it by Polish troops and the troops of the Prussian Confederation were unsuccessful. The castle was taken only thanks to the initiative of Andrzej Tęczyński. In 1457, he negotiated the sale of the Malbork (as well as the castles in Tczew and Iława) to the Polish King Kazimierz IV. For the amount of 190,000 Hungarian florins (about 660 kg of gold), the Czech mercenary commander Oldřich Červenka, who held Malbork as a pledge in exchange for overdue pay, handed the castle over to the Polish ruler. Oldřich also prevented the removal of expensive church equipment from the castle by Grand Master Ludwig von Erlichshausen, who left Malbork together with his mercenaries.

With the signing of the Second Peace of Toruń in 1466, the castle officially began to serve as one of the seats of Polish kings. The upper ward was used as a warehouse, the Great Refectory was a place where royal receptions were held, and the kings’ residence was located in the Palace of the Grand Masters, where audiences were granted. In the middle ward, the northern wing was occupied by the starost, and the eastern wing was occupied by the treasurer of the Prussian lands. The castle also began to serve as one of the most important prisons in the country, where, among others, Filaret, the Moscow Patriarch and co-ruler of Moscow was imprisoned, and also then George Khmelnytsky, son of Bohdan Khmelnytsky, hetman of Right-Bank Ukraine. Moreover, from the second half of the 16th century, a mint operated in the castle, probably located outside the outer ward. Due to the new functions, the castle was rebuilt, among others, in the years 1581-1590.

During the war between Poland and Sweden in 1626, the castle was besieged by Swedish troops under the command of Gustavus Adolf. The Polish defense was commanded by Wojciech Pęczławski, who had 300 men at his disposal. Despite the limited forces and the fact that the Swedes were allowed into the town by Mayor Pheninus, the defenders managed to repel the attacks of 7,500 attackers. Only when the Swedes entered the middle ward from the east through the outer bailey, did the defenders honorably surrender. After capturing the castle, the Swedes built eleven earth bastions within two years. In 1629, the fortifications were expanded by another early modern defensive line, which the Polish troops of Hetman Stanisław Koniecpolski tried unsuccessfully to recapture. Ultimately, Polish troops returned to the castle in 1635, under a truce with the Swedes.

In 1644, as a result of a fire caused by artificial fires in honor of King Władysław IV, the roofs of the upper ward burned down and the cloisters were destroyed. The castle was renovated after 1647 by the Malbork bursar Gerard Denhoff, and shortly later, in 1652, it was handed over to the Jesuits, under whom the cloisters were renovated and rebuilt in the Baroque style. In the years 1655-1660, the Malbork fortress was again occupied by the Swedes. It returned to Polish hands under the Peace of Oliwa, probably in a very bad condition, because in 1675 the roofs over the chapter house in the northern wing and over the southern wing of the upper ward collapsed. In 1691, the roof of the Palace of the Grand Masters was renovated, further repairs and reconstructions also took place in the first half of the 18th century (including the chapel of St. Anne, the middle ward, the Baroque finial of the main tower).

In 1772, with the first Partition of Poland, the castle was taken over by the Prussians who began to rebuild it into barracks. This led to enormous destructions. In the upper ward almost all the Gothic vaults were demolished and the windows were rebuilt, the cloisters were bricked up and a new gate was built on the town side. Many gates and walls were demolished for building materials. After protests from the press and German patriotic circles, the perception of the value of the castle changed. In 1817 the devastation ended and a major restoration began, unfortunately initially carried out in a “romantic” style. More professional activities were carried out from 1850 to around 1876, when Ferdinand von Quast was in charge, and then from 1882 to 1921, when the castle was reconstructed by Conrad Steinbrecht. It was to him that the stronghold owed its radical regothization, preceded by archaeological and architectural research. Despite some wrong decisions, the scale and accuracy of the work carried out generally left a positive mark on history. The rebuilt upper ward was officially opened in 1902, but further renovation works were carried out in the interwar period under the supervision of Bernard Schmid.

Huge destruction of the Malbork Castle occurred in 1945. During the fighting between the Germans and the Red Army, the monument was turned into a point of resistance, which led to the destruction of a large part of the complex, including, unfortunately, the original parts that were not subject to early modern transformations. The eastern part of the upper and middle wards, the main tower and the castle church were completely destroyed. After the war, the Polish authorities established the Social Committee for the Reconstruction of the Castle. Many years of reconstruction began, during which attempts were made to restore its shape from the Middle Ages, remove war damages, as well as erroneous reconstructions made by German art conservators.

Architecture

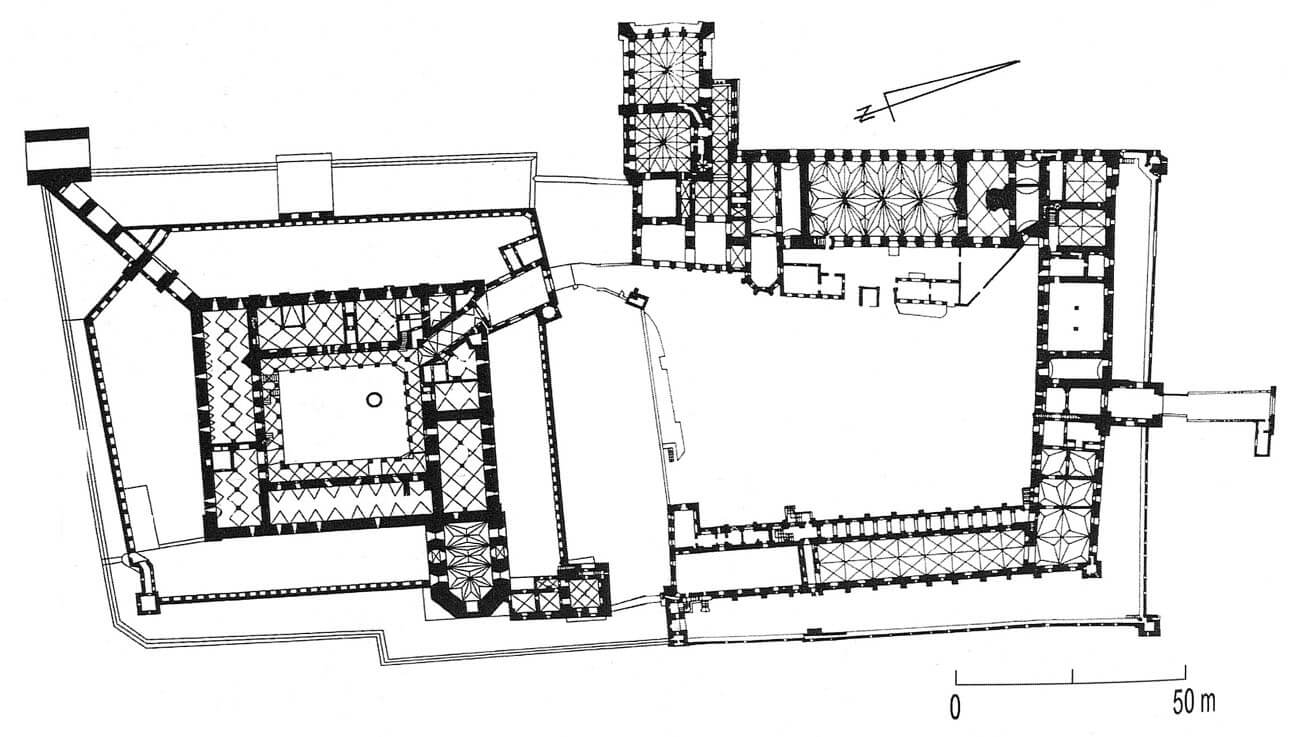

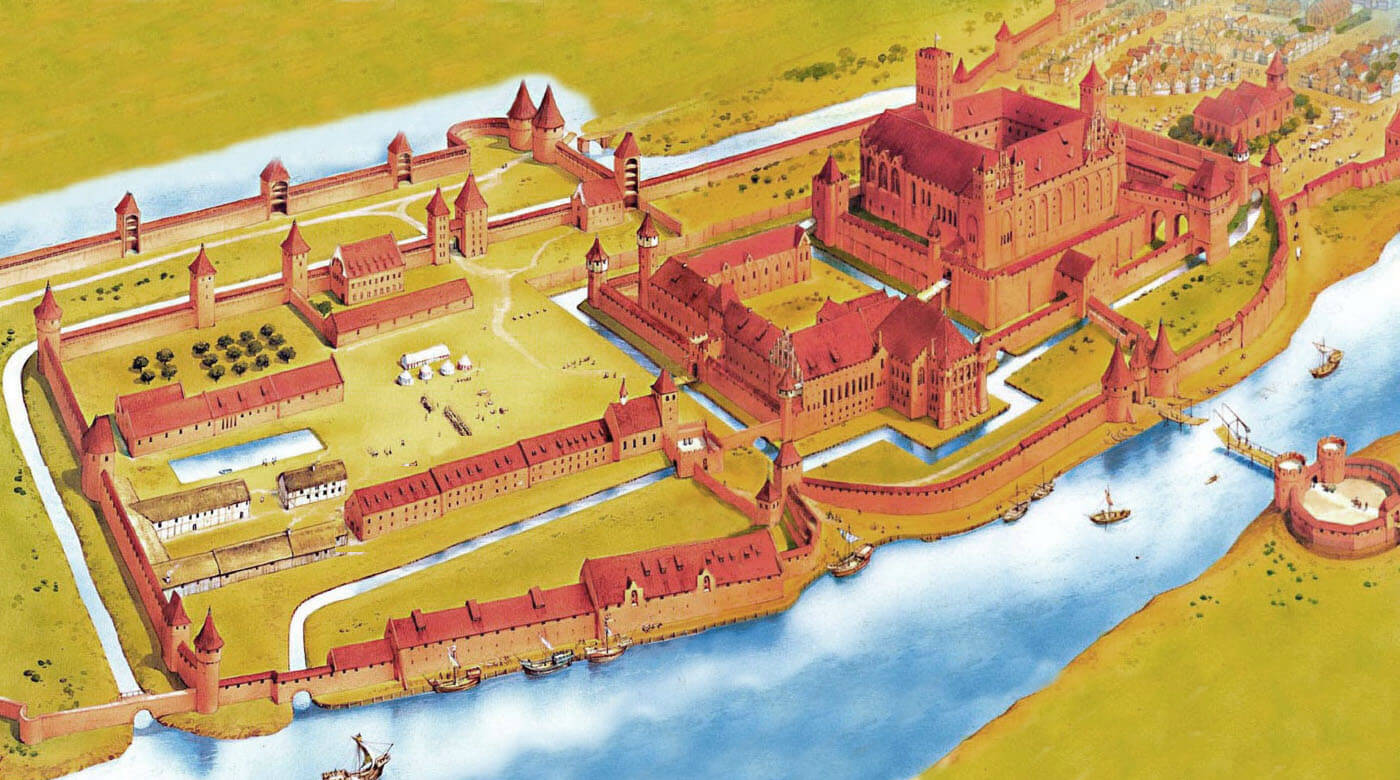

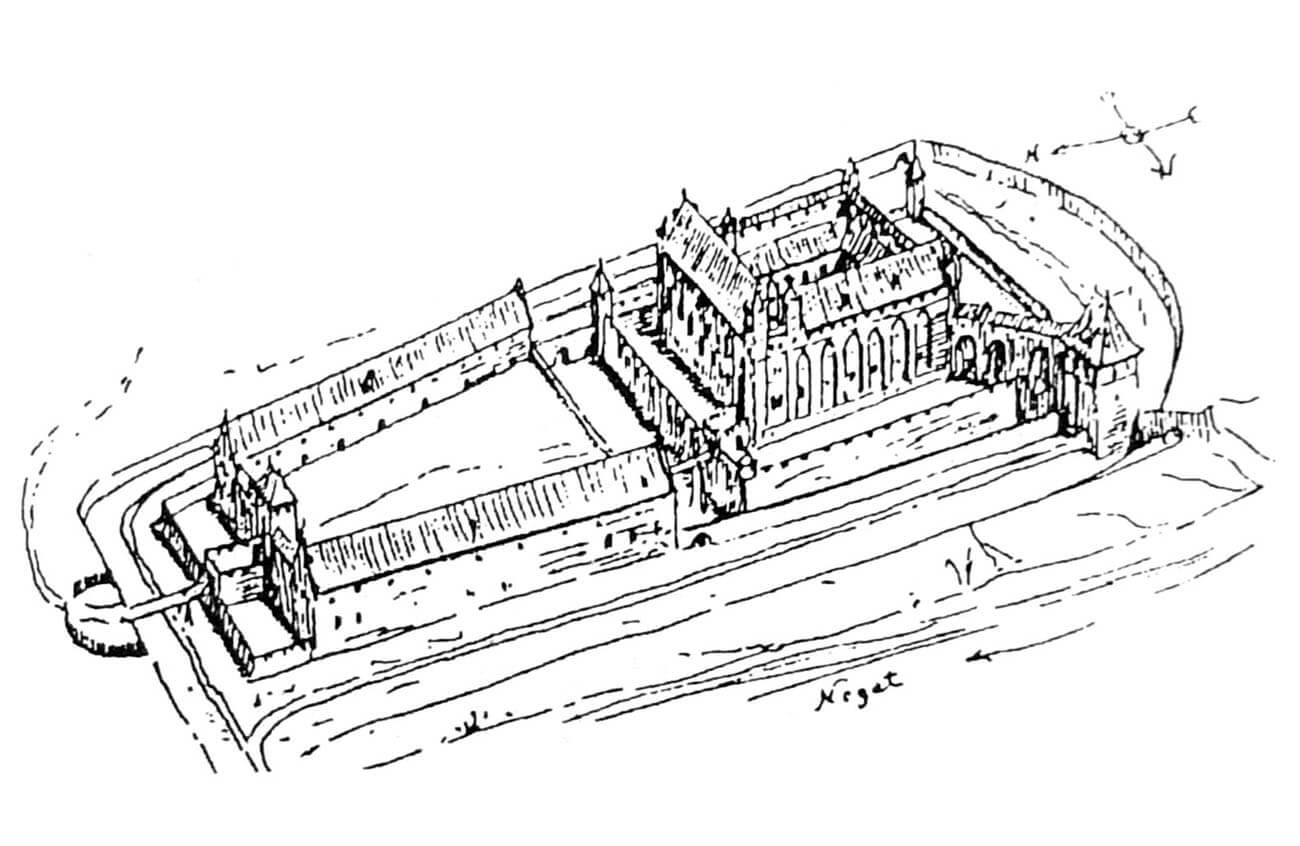

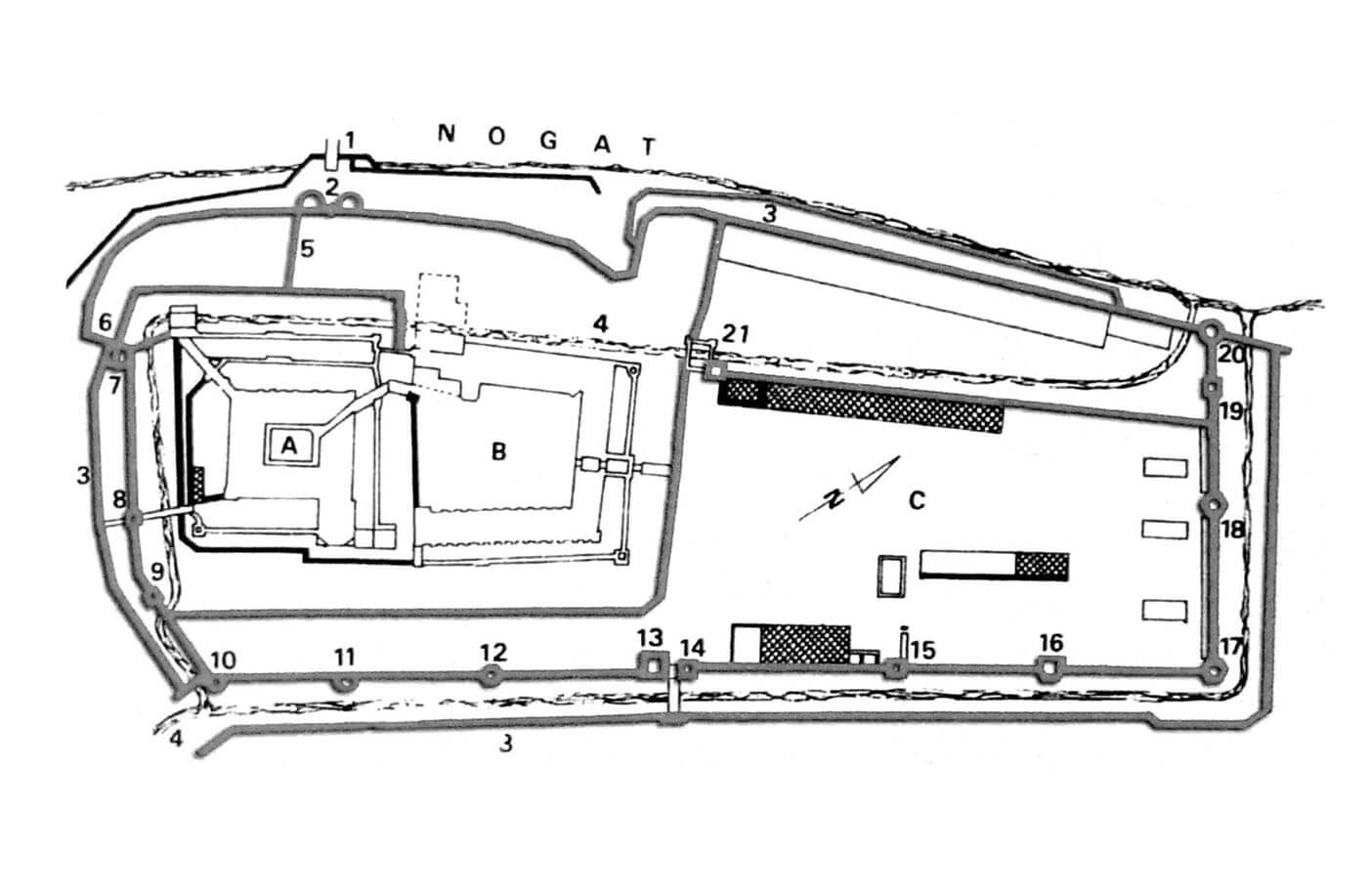

The Teutonic seat of the Grand Masters in its final shape consisted of three main parts: a high (upper), middle and lower wards. The whole area covered a huge area of about 21 ha, arranged on a plan similar to a rectangle with dimensions of about 600 x 250 meters. The basic materials for the construction of the castle were brick, limestone and granite. Foundations and elements exposed to destruction were built from granite, architectural details were made from limestone, and bricks and wood were used to construct the main parts of the building. The castle was placed on the right, eastern bank of the Nogat, in a naturally defensive place. Originally, it was a long strip of land, raised 10-15 meters above the river level, surrounded by a river from the west and partly from the north, and by vast swamps from the east. On the southern side of the castle, a settlement developed, granted a town privilege in 1276 and from the 14th century surrounded by its own defensive walls. Individual parts of the castle were separated by irrigated moats, ditches and in addition, from the east and north, the whole was surrounded by the Mill Canal.

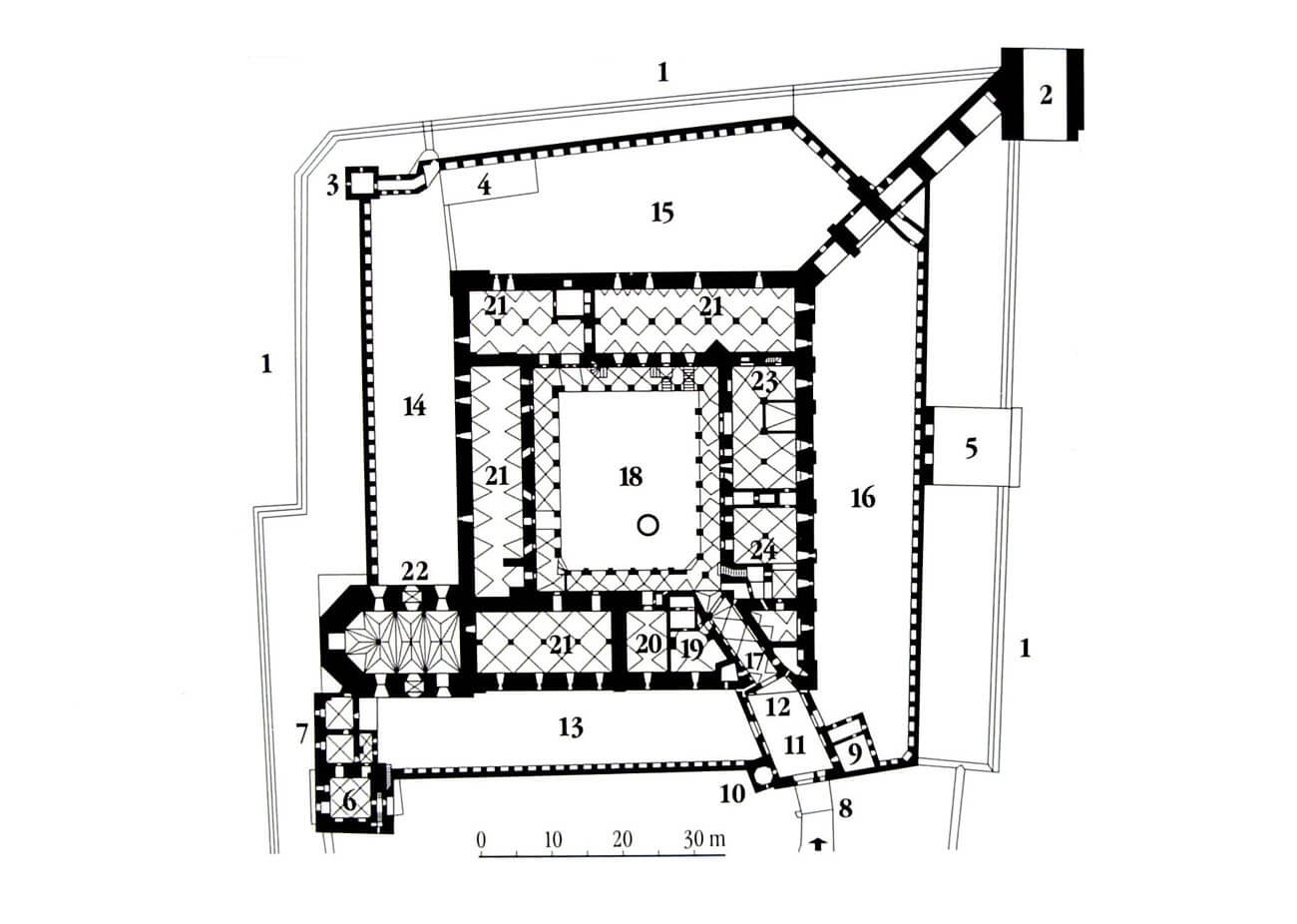

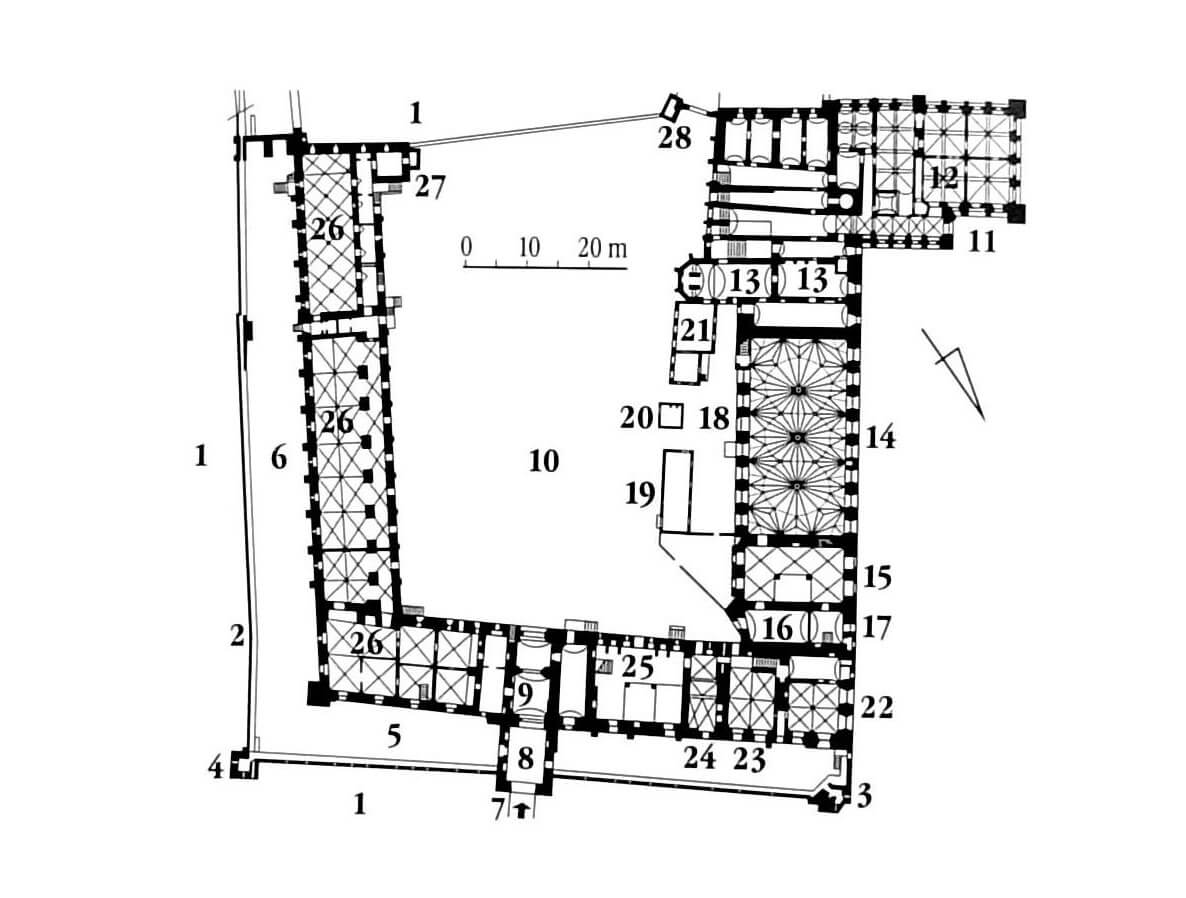

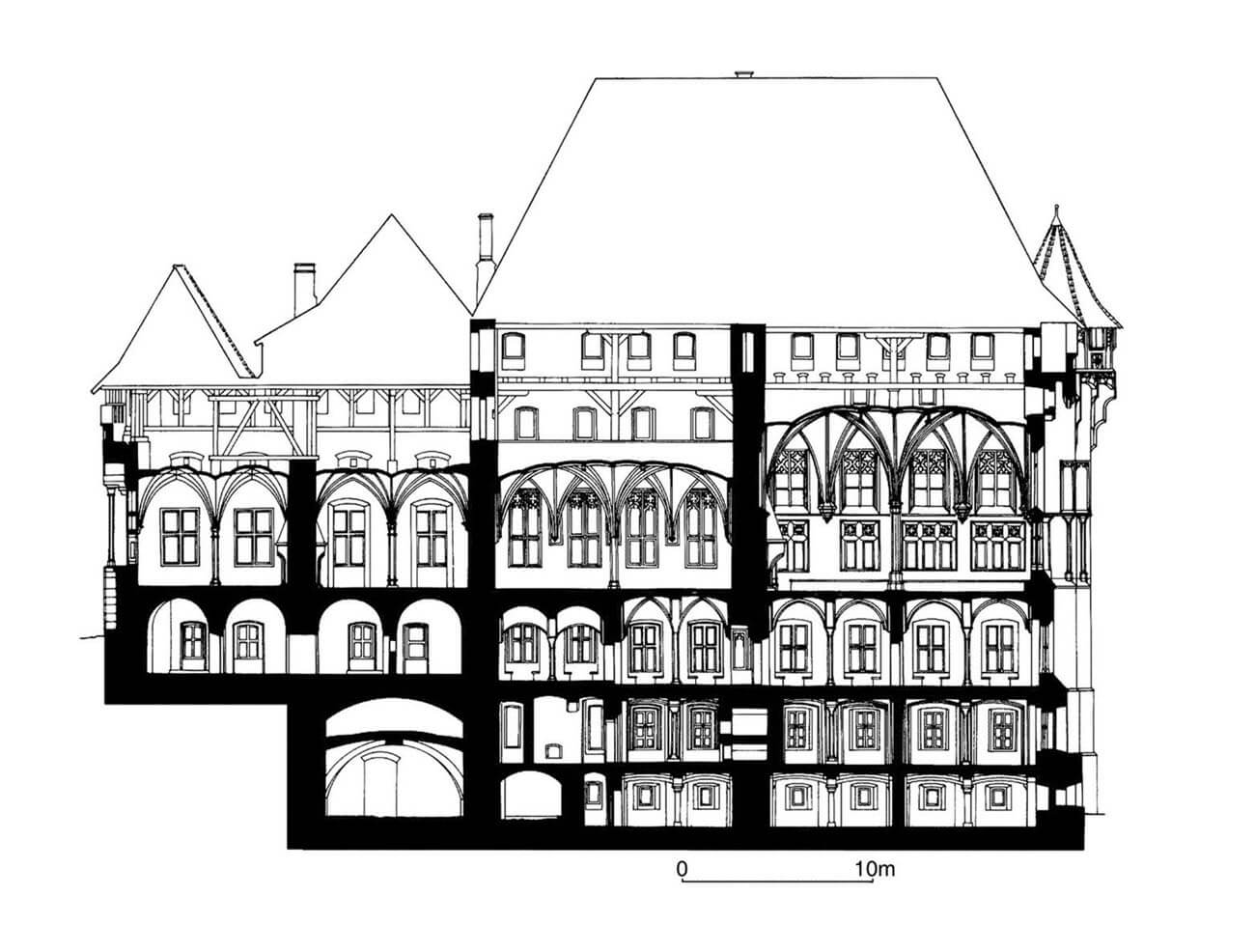

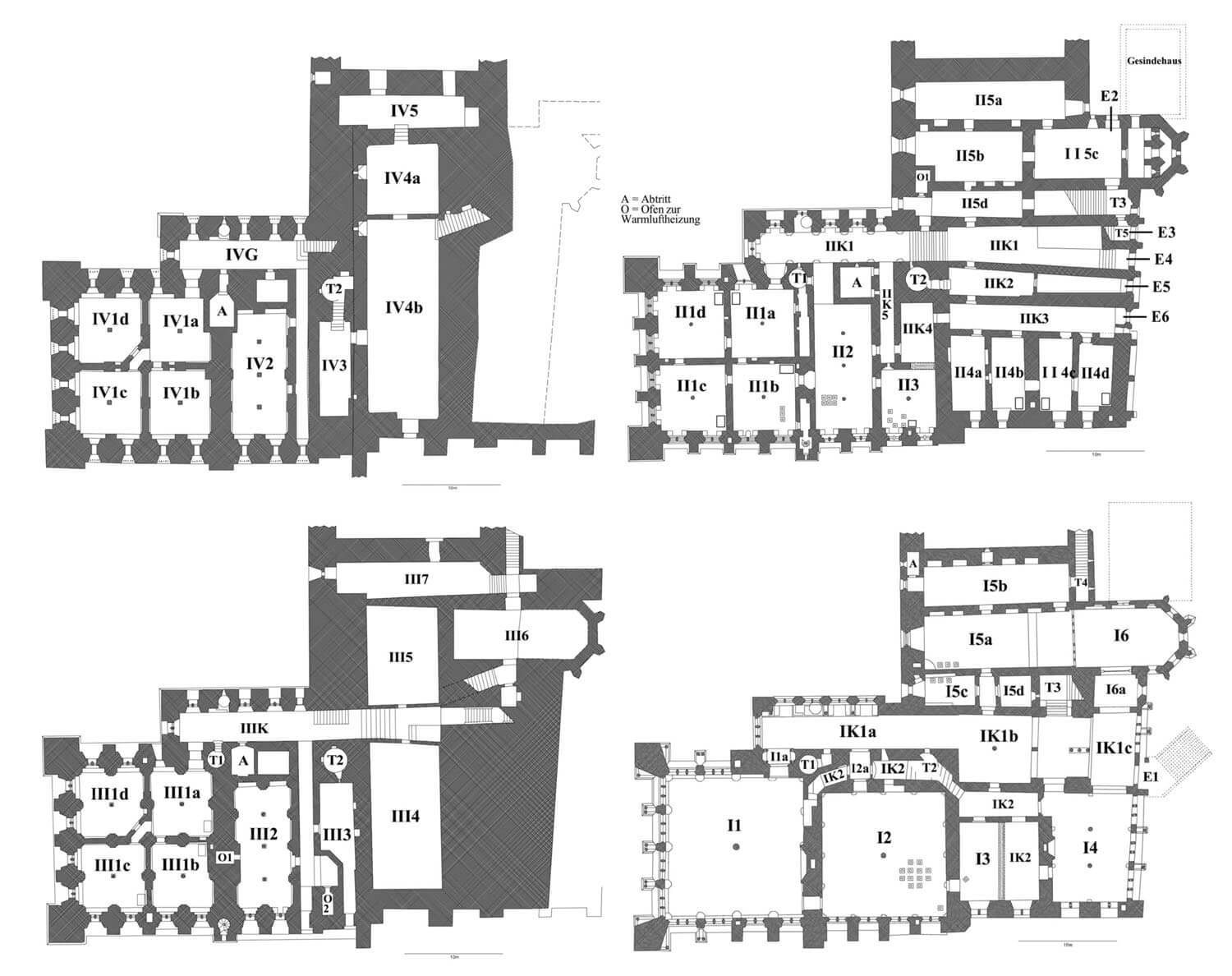

The seat of the Teutonic Knights commandry was the upper ward, built in the southern part of the complex on a rectangular plan with sides of 51 x 61 meters. It consisted of four wings surrounding a courtyard measuring 32 x 37 meters. From the mid-14th century, all four wings had the same height and were covered with gable roofs, with the northern and southern wings based on gables decorated with pinnacles and blendes, covering the entire width of the sides, and the remaining two wings were set between the first ones. In addition, the three outer corners of the upper ward received four-sided turrets measuring 3.7 x 3.7 meters, which made the castle’s shape more slender and finesse. All of them were slightly protruded in front of the face of the wing walls, but the southwestern one was the only one located at an angle, due to its connection with the dansker (latrine) tower. Additionally, the western gable of the northern wing and the eastern gable of the southern wing were flanked with further similar turrets. Unlike the corner ones, they were not extended in front of the walls, but only built from the level of the roof eaves, so they were only accessible from the attic. The main tower was built into the eastern wing – a bell tower and a watchtower measuring 11.7 x 6 meters and 66 meters high. Like the corner turrets, it was topped with battlements. The northern wing was extended towards the east before the mid-14th century to house the church and the castle chapel.

The external facades of the upper ward were separated by numerous windows of various sizes and shapes: ogival, quadrilateral, segmental. The western façade facing the river was distinguished by six large, pointed-arched niches, while smaller, plastered blind windows were also placed in the south, on the town side. Moreover, the walls were decorated with arcade friezes with tracery, plant and human heads motifs, and geometric patterns made of zendrówka bricks fired to a black color. The richest were the external facades of the polygonal closure of the castle church, divided into three floors. On its ground floor there were portals on the north and south and two pointed windows with deep splayds. The upper part was separated by a stone cornice and divided by moulded pilaster strips, ending with a wreath of triangular, decorated with tracery wimpergs, separated by pinnacles. The main floor had eight impressive windows with richly moulded splayds (except for the extreme western windows), separated by buttresses with blind tracery decoration. In the place of the central eastern window, there was originally an 8-meter-high statue of Mary with the Child and a scepter, set in a deep, pointed niche. The figure was made of artificial stone, covered with mosaic and colored.

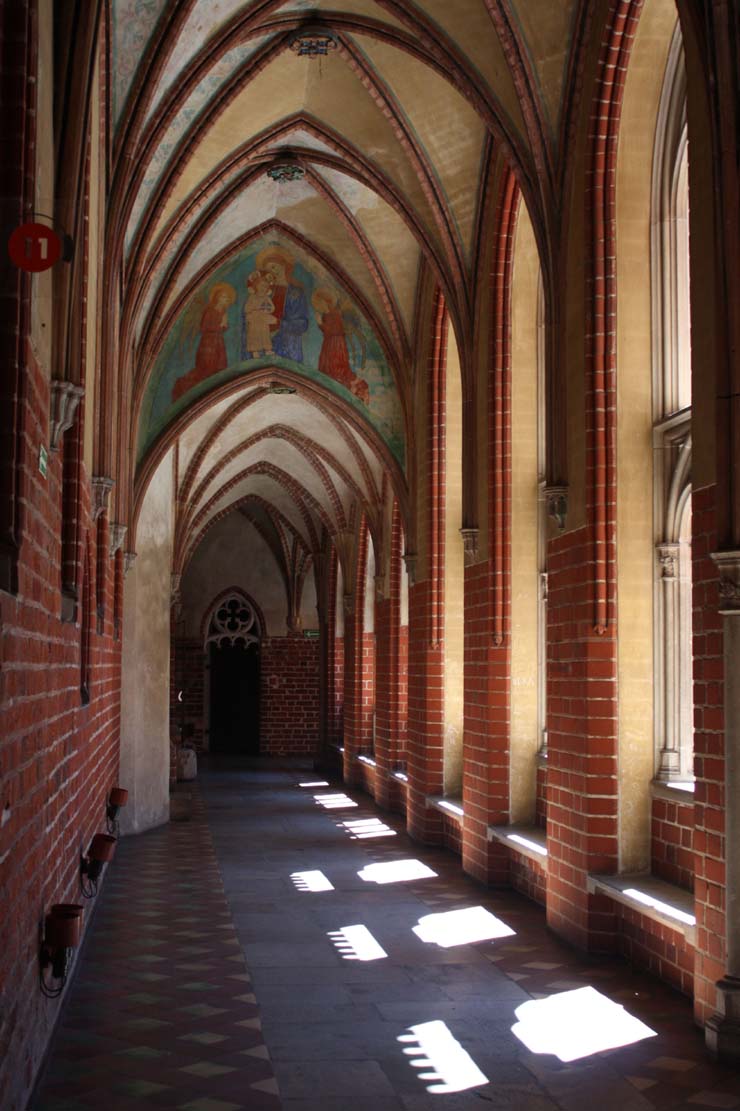

From the 14th century, the inner courtyard of the upper ward was surrounded by two-story and from the south by three-story cloister, cut in two corners, with the main storey in the southern wing and in the western part of the northern wing being higher than in the other parts. The cloisters were based on massive pillars made of bricks and granite and on slender granite columns on the ground floor of the western wing. Between them there were pointed arcades, and above, on the axes, two-level lesenes decorated with blind tracery. The pointed arches of the first floor of the cloisters were filled with tracery, mostly in three-light forms. The ground floor of the cloisters was covered with a groin vault, and the first floors were covered with a cross-rib vault, set on bas-relief corbels with images of animals and people, although the western part on the ground floor could only have been covered with a timber ceiling. In the center of the courtyard there was an 18-meter-deep well.

The entrance to the upper ward was located at an angle in the western part of the northern wing. Its unusual layout may have resulted from topographical reasons, from the desire to increase defense or simply from a change in the architectural concept. The main gate was placed in a high, ogival recess, housing machicolations. The archivolt of the recess was set on slender semi-columns with capitals decorated with knightly scenes. Black-glazed bricks were placed in the lower parts of the niche, on its edges and in the arch, as well as in the arches of the two pointed windows above the passage. The pointed gate opening, 3.7 meters high, was made of granite. Its archivolt was chamfered, and above it there was a ceramic frieze with trefoil motifs. The gate was accessed by a drawbridge over the moat, and an elongated foregate with a keykeeper’s house and a corner octagonal turret, with a spiral staircase inside leading to the dry moat.

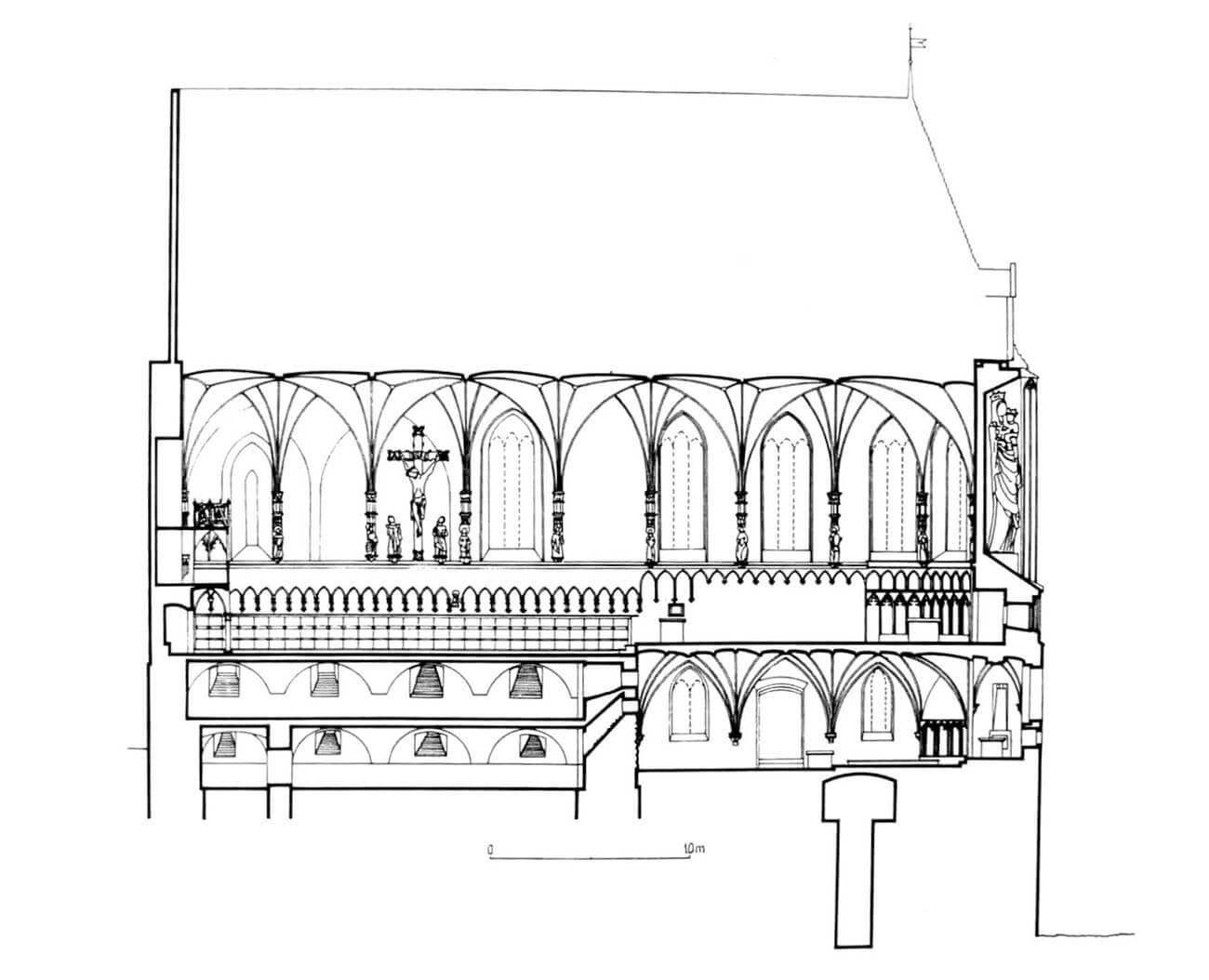

From the mid-14th century, the wings of the upper ward were three- and four-story, with basements of which the northern and western wings had two levels. Traditionally, in Teutonic Knights castles the basements were intended for storage and pantries, the ground floor was used for economic purposes, and the first floor housed the most important residential and representative chambers. Additionally, the mezzanines and attics were used as granaries and for defensive purposes, because there was a defensive gallery in the crown of the walls, about 1.1-1.2 meters wide, located on the outside façades and connected to the corner turrets. Access to it was provided by three spiral staircases in the thickness of the walls (in the north-west corner, in the main tower, in the south wing). The main rooms on the first floor were heated by three hypocaustum furnaces located on the lower floors.

In the eastern wing, at first floor level, in addition to the main tower room, there was one large room, six bays long, covered with a cross-rib vault and illuminated by eleven irregularly placed windows from the outside. Perhaps it served as a dormitory, a common sleeping room for the monks. In the southern wing, the main floor was occupied by two rooms of different sizes. The smaller eastern one with four bays was divided into two aisles by three pillars. The longer western one had a vault supported by seven round, granite columns. Unusually, it was cut diagonally by a porch leading from the dansker, and also connected to the cloister and the adjacent room by a portals. The southern wing was distinguished by a second representative floor, probably with the same layout. The kitchen and bakery were located on the ground floor of the west wing. Above, there was probably a row of living quarters for the commander and the treasurer, or the oldest chambers of the Grand Master. After the reconstruction in the first half of the 14th century, several small rooms were created, probably housing from the north: a staircase, the chamber of the Great Treasurer, a treasury, six rooms for the Malbork Commander, the Household Commander and the kitchen chef.

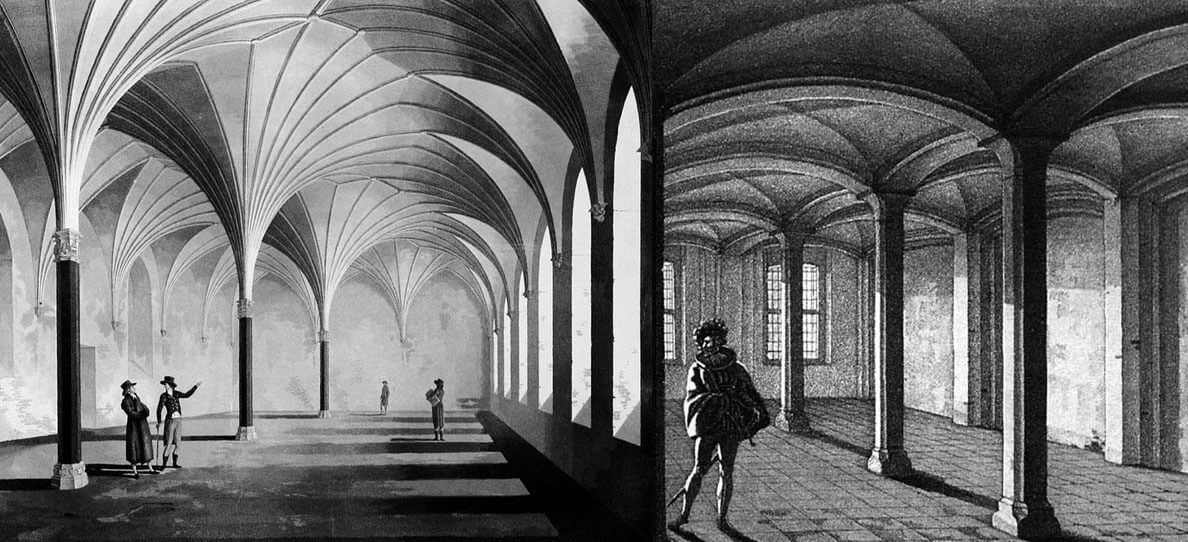

In the northern wing, on the main floor, there were three rooms. In the western part, it was a representative chamber, once identified with the chapter house, originally rather serving as a refectory, then an intermediate room 5.1 meters wide, perhaps serving as an archive, and the church of the Blessed Virgin Mary on the eastern side. The refectory was initially two-bay and covered with a cross-rib vault with two granite columns. After 1331, the central room was demolished, the two-bay representative room was enlarged, and the eastern part of the wing was extended. After the reconstruction, the refectory had impressive dimensions of 18.3 x 9.9 meters, divided into four bays with a stellar vault, based on slender, octagonal, granite columns and wall shafts. In the corners, the stellar vault was complemented by three-support vaults. Since the end of the 14th century, the facades of the refectory have been decorated with painted portraits of Grand Masters with inscriptions commenting on their figures. Access to the chamber was provided from the south from the cloister by a pointed, moulded portal with capitals with floral motifs, decorated on both sides with black, glazed bricks.

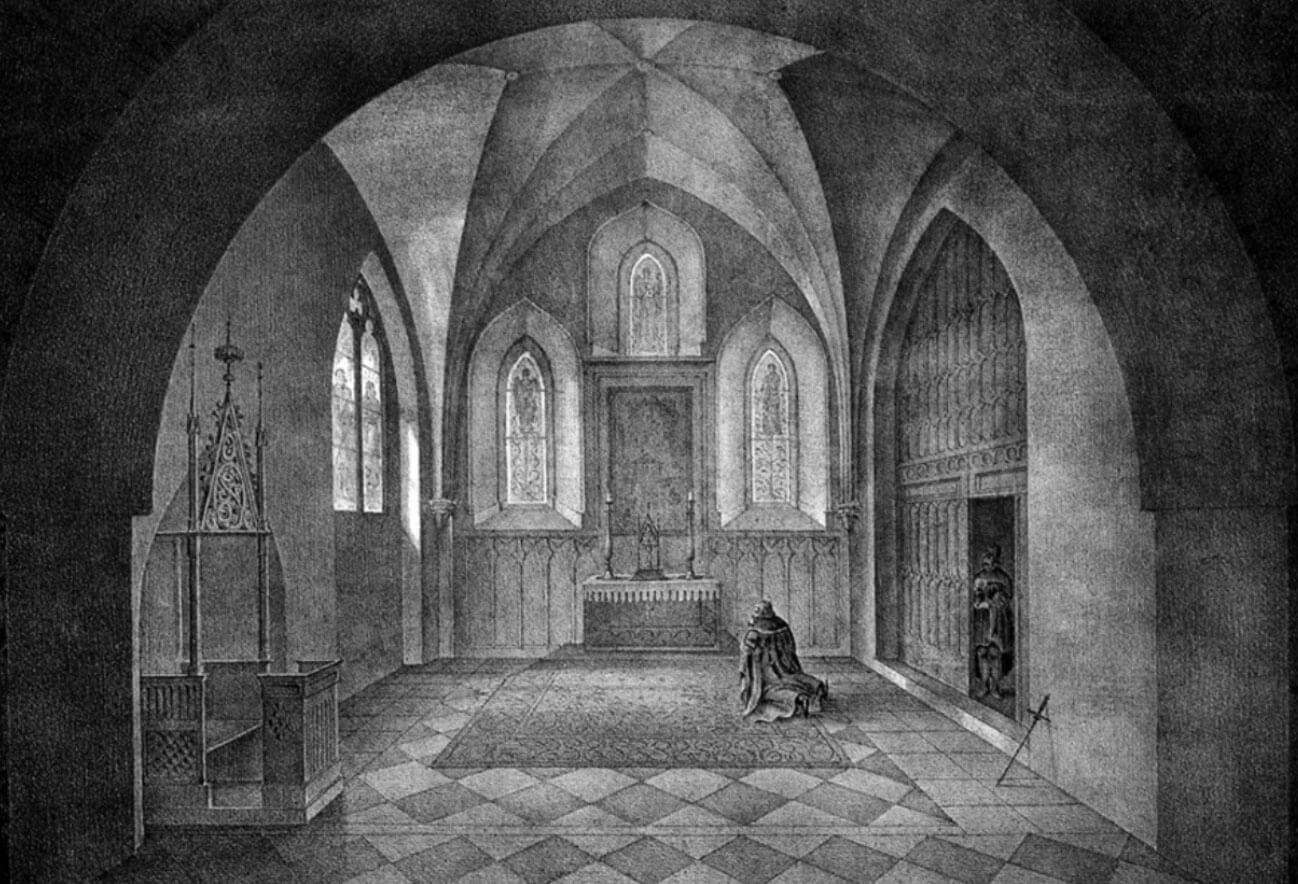

The eastern part of the northern wing at the first floor level was initially filled with St. Mary’s Chapel. It probably had dimensions of 19.8 x 9.9 meters and a height of about 12 meters. Its interior was divided into three bays, aisleless, with a polygonal closure of the chancel, covered with a cross-rib vault based on wall-shafts. The facades of the chapel were decorated with blind arcades formed by semi-columns with capitals. Moreover, in the western wall of the chapel there were three wide, pointed niches, each with two openings leading to the central room of the wing. The western part of the chapel was filled with a gallery 0.7 meters wide, with a protruding polygonal central part in the form of a pulpit, supported by two columns. A spiral staircase and a small cell with a groin vault were created in the thickness of the wall, perhaps used to present relics.

The entrance to the chapel led through the so-called Golden Gate, a decorative portal from around 1280, located next to the cloister in a small porch in the thickness of the wall, with a cross-rib vault and a wall arches decorated with blind tracery. The portal owed its name to rich polychrome sculptural and painted decoration, which, in keeping with the spirit of the Middle Ages, also had a symbolic meaning. The portal was sculpted with seven orders with semi-columns and a capital zone in which plant ornaments and a bestiary (figures of mermaids or harpies) were created. Above, in a beautiful pointed archivolt, were made among others: the parable of the Foolish and Wise Virgins and the statues of Ecclesia and the Synagogue. In the top of the internal archivolt there was a bust of a man placed. The decoration of the portal was related to the double recesses in the walls of the porch, where terracotta bas-reliefs were placed against the background of a striped decoration of brown and black glazed ceramic tiles.

The reconstruction in 1331-1344 transformed St. Mary’s Chapel into an even more impressive church of the Blessed Virgin Mary, 38 meters long and 14.4 meters high. The original space was extended by one and a half bays towards the east, but the aisleless layout was retained. The church had a stellar vault divided into four nearly square bays, nine-pointed in the eastern part and eight-point in the remaining part. Rich architectural details were introduced into the interior: carved bosses, polychrome ribs, two rows of blind wall arcades in the chancel, a painted frieze with an inscription, and an arcade frieze with a small offset resulting from the raised level of the chancel floor. The church vault was based on wall shafts, which were decorated in a sophisticated way. Under their heads there were canopies with almost life-size statues of the 12 apostles, resting on consoles with images of evil powers. The church was lit by high, pointed windows, glazed with colorful stained glass with figural motifs and filled with tracery, but due to changes in the length of the bays during the rebuilding, the old windows were bricked up, except for one from the north. The walls of the church were so massive that they allowed for the creation of as many as four sacristies in their eastern part, all covered with cross-rib vaults. Additionally, a small penitential cell was placed in the southern wall. After the reconstruction, the western part of the church was still filled with gallery (matroneum).

Under the two eastern bays of the church of the Blessed Virgin Mary, the chapel of St. Anna was located, planned to be the burial place of Great Masters. In its 3-meter-deep crypt, under the floor, the bodies of deceased Great Masters wrapped in a shroud were placed on a catafalque. After the death of the successor, the remains of the predecessor were slid into an 8-meter-deep adit, carved under the catafalque, which was to be filled with earth brought by the monks from the Holy Land. The chapel itself had three bays, a polygonal eastern closure and an apse created in the thickness of the wall. It was covered with a four-pointed stellar vault, in the chancel a six-pointed one, fastened with bosses with figural representations of saints, Christ, animals, mythical beings, symbols of the evangelists and the coat of arms of the Great Masters. The ribs of the chapel were springing from the carved consoles, among others decorated with figures of Atlantes. Moreover, pointed blendes with bas-relief male heads were placed under the windows. The entrance to the chapel led through portals from the north and south, in front of which there were opened porches and vaulted vestibules in the thickness of the walls. The portals were decorated with figural tympanums, and the porch walls were decorated with blendes, above which there were apparent tympanums in the wall arches.

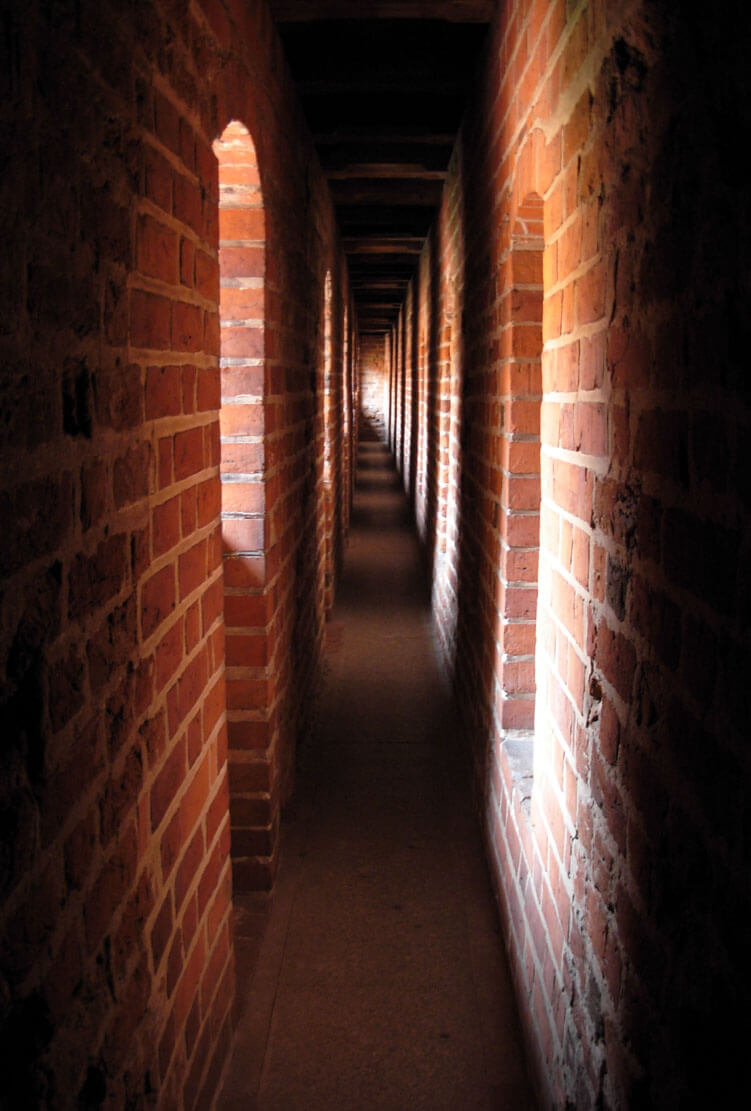

The upper ward was surrounded by two outer walls and a moat, which was supplied with water from Lake Dąbrówka, approximately 8 km away, through a specially dug canal. It was decided that one could not rely on the Nogat River, as the water level was too unstable, and moreover, thanks to this investment, the castle’s mills were also able to operate. The area of the eastern zwinger was designated as a cemetery for Teutonic knights. There were also castle gardens in the zwinger area, including rose garden on the south side. In the northern part of the first zwinger there was to be the castle Commander’s House, the Treasurer’s House, the so-called Summer House, and the Priests’ Infirmary. There may have been a mill in the area of the second western zwinger. On the south-west side, both zwingers were cut diagonally by a brick porch based on five pointed arcades, leading to a dansker (latrine) tower protruding about 60 meters (originally the first arch of the porch was equipped with a drawbridge). The dansker itself had the form of a four-sided tower with dimensions of 12.6 x 13.3 meters, protruded in front of the perimeter of the second defensive wall, set on two pillars above the moat.

The first (internal) wall of the zwinger had a relatively irregular course compared to other Teutonic Knights castles, characterized especially by a truncated south-west corner. On the inside, on the ground floor, it had a row of segmental recesses, above which there was a guard’s wall-walk. It did not run around the entire perimeter of the upper ward, because on the eastern side it connected with the chancel of the church of the Blessed Virgin Mary (you could pass underneath it through the chapel of St. Anne on the ground floor). The zwinger wall was strengthened by a slender four-sided tower in the south-east corner. Called the Sparrow’s Tower, it was connected to a small house, from 1413-1414 intended for the Grand Master’s advisor, and then for the porter guarding the neighboring postern from the castle to the town. Moreover, from the second quarter of the 14th century, in the north-eastern corner of the upper ward, in the line of the first wall of the zwinger, on the lower walls of the older, 13th-century tower and the small arcaded dansker, the residential Klesza Tower was built and the adjacent so-called The Bell Ringer House. Inside it had the chambers of the brothers – priests serving in the castle church. The entrance to the Klesza Tower led from the zwinger, to the barrel-vaulted rooms on the ground floor, under which there was a basement, and above which there was an upper floor covered with a groin vault. The second, outer wall had a much narrower section of the zwinger, exceptionally narrow on the southern side. Just in front of the line of this wall there was the above-mentioned tower of the large dansker, but there were probably no other towers. On the northern side, the wall of the second zwinger ended and was replaced by a moat separating the upper ward from the middle ward.

The middle ward was originally the outer bailey of the upper ward, i.e. the economic base for the commandry, in the form of a quadrilateral with sides of approximately 80 and 100 meters. In this first phase, it had perimeter walls with four square towers in the corners and two impressive buildings along the eastern and western curtains, 27.5 and 32 meters long respectively. They probably served economic purposes as granaries, it may also contained stables, a coach house or barns. From the north, between the two curtains, there was a gatehouse with a passage on the ground floor.

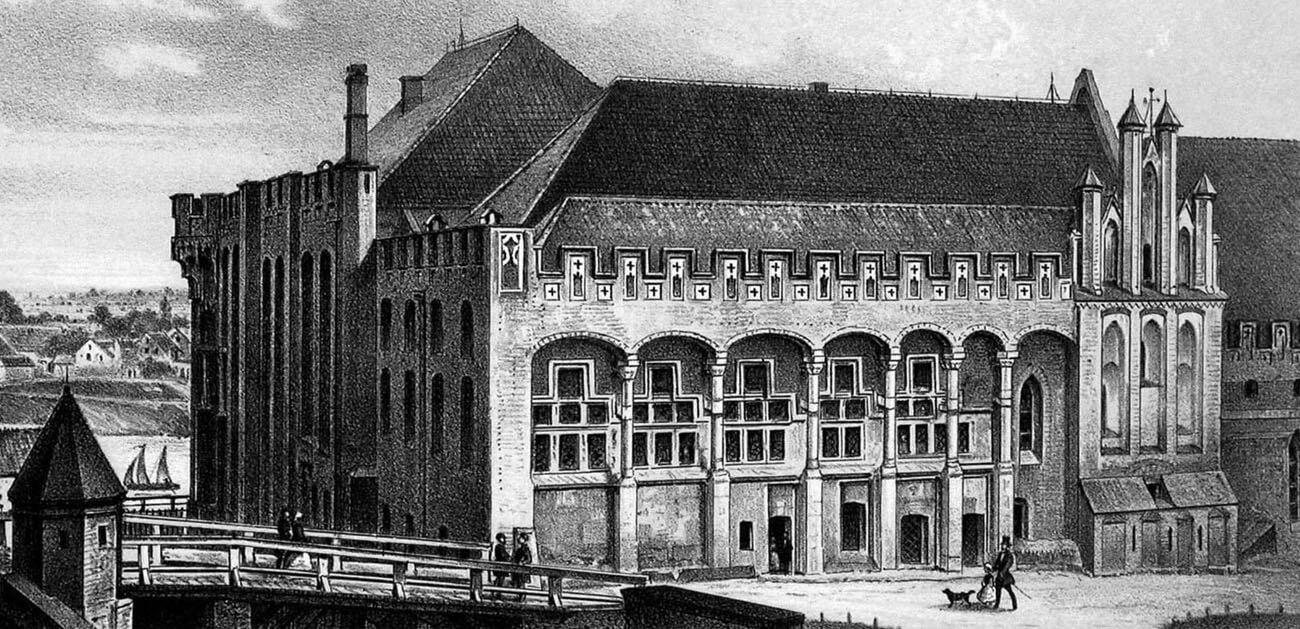

In the second quarter of the 14th century, the outer bailey was rebuilt into a middle ward, roughly repeating the dimensions of the older complex (only the western wall of the original outer bailey was moved 4 meters to the west). It contained mainly representative and administrative buildings of the Teutonic state, so it had to be properly secured. From then on, the middle ward from the north and east was protected by an outer wall forming a zwinger, with a north-eastern corner turret measuring 3.5 x 2.5 meters. Moreover, before the mid-14th century, another wall line was created, surrounding the upper and middle wards, connected to the wall of the lower ward in the north, and to the Malbork town walls in the south. The buildings of the middle ward formed three wings, approximately 75 meters long, surrounding a trapezoidal courtyard, which from the side of the upper ward was closed only by a low curtain and a wide moat. This was probably a deliberate intention of the designers, according to whom the upper ward was to dominate with its massive, lofty shape and emphasize the strength of the order, and at the same time, the buildings of the middle ward could not constitute an obstacle to the defense of the upper ward in the event of being captured by enemies.

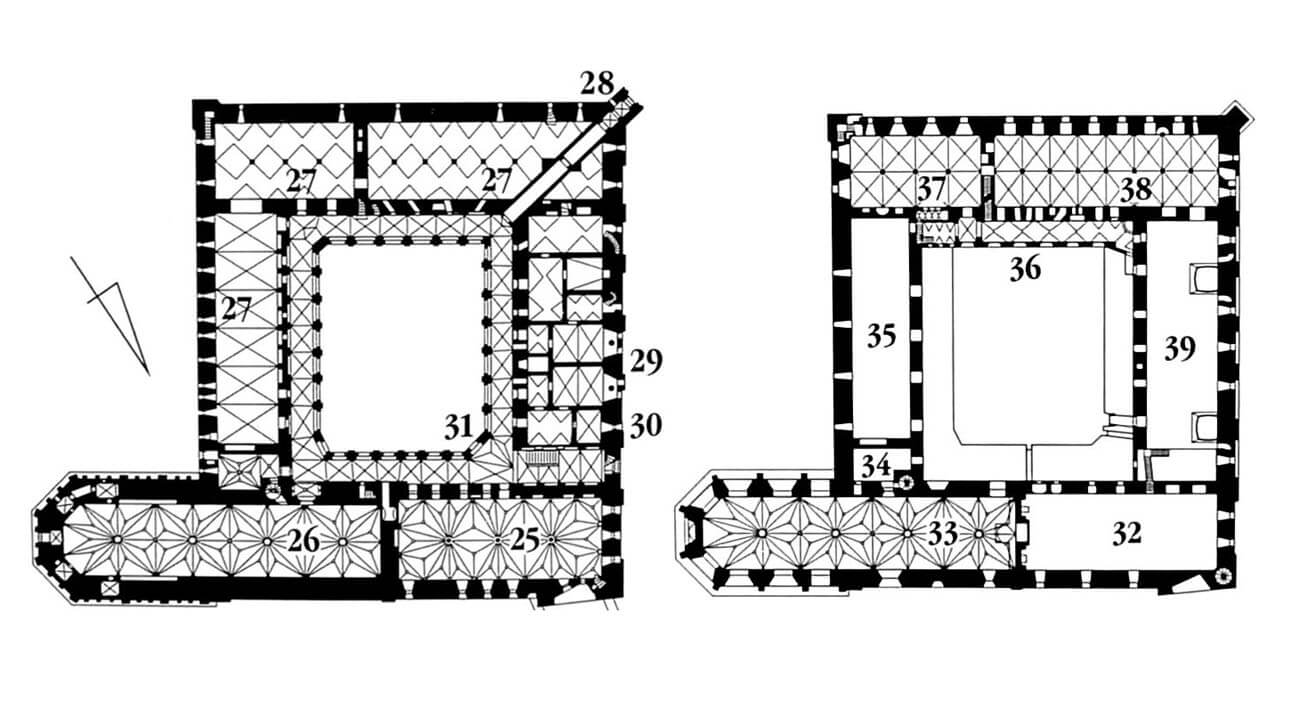

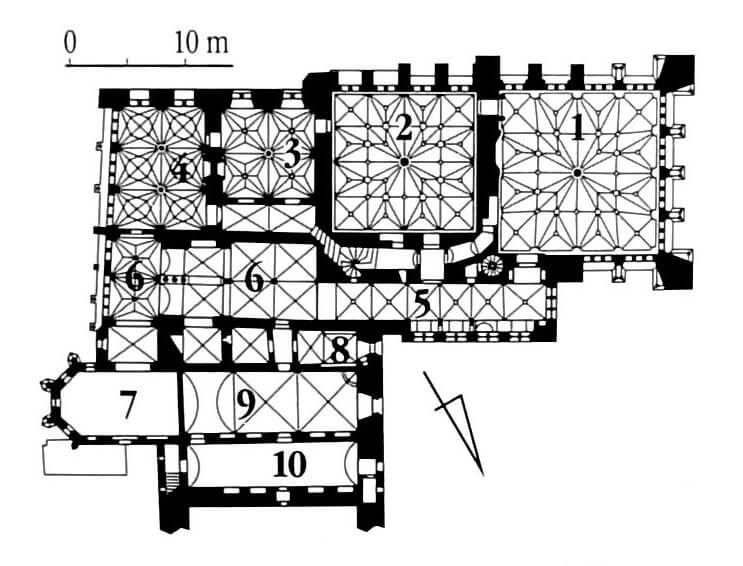

In the 1330s, at the western curtain of the middle ward, on the basis of an older economic building, the Great Refectory was built, and next to it the first Palace of the Grand Masters, connected to a private, two-story chapel of the Grand Masters, later dedicated to St. Catherine. Initially, the palace had an elongated, relatively narrow, rectangular plan, although on the western side it could be enlarged by an avant-corps supported by three large buttresses facing the river. On the opposite side, the building probably opened onto the courtyard with an arcaded cloister. The chapel consisted of two rectangular bays and a polygonal closure with buttresses in the corners. It extended towards the courtyard, perpendicular to the western wing, with which it did not touch by the western wall (it ended approximately 2.5 meters in front of wing). The only direct connection of the chapel with the staircase of the Great Refectory was on the short northern section. Between the outer wall of the palace and the western wall of the chapel, there was probably a passage extending the cloister, probably covered with a common roof with the main part of the building.

Inside the first palace, a vaulted cellar was used to store barrels of wine and beer belonging to the Grand Master, while further north there were long basement rooms under the Great Refectory where food for the kitchen were stored. The southern basement was accessible through a door from the moat, from where it was possible to reach the nearby ship harbor. Several additional stairs led to the basement from the courtyard. In the middle of the upper basement level, a low barrel vault was introduced, serving as a foundation for two transverse walls dividing the upper space of the residence into three main parts, perhaps further divided by lighter wooden screens. There could have been an office and living quarters there. On the next floor at the northern end was the Grand Master’s apartment, equipped with wall shelves, a latrine and an entrance to the Great Refectory. There was probably a second living room adjacent to it, and from the east there was access to a private chapel. The latter was covered with a cross-rib vault above the upper storey, and a barrel vault above the lower storey. To the south of the residential zone there was the Council Chamber and a smaller refectory, which, being located at the extreme, could be well lit on three sides.

From the second quarter of the 14th century, the most important room in the western wing was the Great Refectory, the largest chamber created in Teutonic Knights castles, used for chapter meetings, audiences and daily meals of the Grand Master with his court and invited guests, who were supposed to be dazzled by the splendor and wealth of the Teutonic Order. It was a spacious rectangular room with dimensions of 30 x 15 meters, topped with a rib vault with a system of interwoven stars, supported by three slender, octagonal, granite pillars, 3.3 meters high. Similarly to the refectory (chapter house) of the upper ward, the composition of the vault in the corners was supplemented with additional ribs. The pillars were equipped with capitals decorated with plant motifs and human figures (e.g. a procession of jesters, scenes from the life of Adam and Eve) and with bases decorated with masks and leaves. On the wall corbels there were among others images of a bishop, a monkey and a dog. The room was illuminated by large, pointed windows with colorful stained glass, six on the eastern side and eight on the western side. The entrance was through a portal from the courtyard. The internal facades were covered with colorful wall paintings (a large scene of the coronation of Mary, a procession of mounted knights carrying banners). The room was heated with warm air from the furnace, coming through channels placed in the floor. From the south, the Great Refectory was connected to the Grand Master’s chambers, and beneath it the basements housed warehouses and a hypocaustum furnace. The external facades of the refectory were left in raw bricks. The only decorative element was a horizontal plastered frieze with painted tracery decoration, running under the defensive porch.

In front of the Great Refectory and the chapel, there was a small courtyard that separated the palace space from the large square of the middle ward. Directly next to the chapel, on its northern side, there was a guardhouse, to which the building of the main gate of the residence was adjacent. Every visitor who wanted to get to the Great Refectory or the representative floor of the Palace of the Grand Masters had to cross it. This was the only permanent access control to the residence, as the palace was otherwise unprotected by guards. In the northern part of the small courtyard there was the Grand Master’s bathhouse, which consisted of three rooms: a bathing room, a vestibule and a changing room. Each of them had separate heating using hot air forced from the hypocaustum furnace in the basement.

The western wing of the middle ward in the northern part had a two-level basement. On the ground floor there were vaulted pantries, a bakery, a kitchen and a chef’s chamber. There was also an infirmary, a hospital for sick and old monks. They had their own two-bay chapel on the ground floor (in the adjacent northern wing), a refectory, a bathhouse, and bedrooms on the first floor. The infirmary refectory had a stellar vault on a single pillar. The external façade of the infirmary was decorated with a large, triangular, seven-axis, stepped gable, decorated with ogival blendes on four levels, and above with pinnacles and wimpergs with round wind holes. It was supposed to be visible from a distance and dominate the entrance to the middle ward. From the corner of the infirmary a wall of a zwinger started with a small latrine tower (the so-called Kurza Stopa), which was accessed by an overhang wooden porch.

In the northern wing, on the ground floor, approximately in the middle part, there was a gate passage, preceded by a simple foregate connected to the zwinger wall. Access to it was protected by a drawbridge over the moat separating the lower ward from the middle ward. At the gateway, in the area originally occupied by the older gate tower of the middle ward, a new tower was built in the second quarter of the 14th century, embedded in the northern wing. The ground floor rooms on its sides probably had auxiliary and utility functions for the guards, while the first floor had vaulted residential rooms. The wing also had cellars, except for part under the gate passage itself, and an attic serving as a granary with a defensive gallery on the outside, i.e. facing the lower ward.

In the eastern wing of the middle ward there were rooms for the guests of the Teutonic Knights, including crusaders, representatives of European countries and their retinues, as well as a small church of St. Bartholomew, added at the end of the 14th century. The church was extended 5.2 meters towards the courtyard, thanks to which it had three bays with a cross-rib vault. The ground floor and basements of the wing of course served economic and storage functions. Similarly to the other wings, there was a hypocaustum furnace in the basement, heating the upper two floors. The ground floor and the first floor were divided into two main spaces, eight-bay in the north and seven-bay in the south, probably covered with a cross-rib vault along their entire length, and separated by a passsage and porch on the first floor. Thanks to movable partition screens, their interiors could be freely arranged. Communication was provided by a narrow passage from the courtyard side, with numerous entrances, on the first floor, above which there was an attic. The façade of the eastern wing on the courtyard side was decorated with a number of large, ogival blendes with large windows and entrances to the ground floor rooms, and on the eastern side it was divided by a number of buttresses, between which there were ogival recesses with windows. The main floor was separated by a cornice, bent around the recesses. Above there were windows of the defensive gallery, between which there were originally pierced loopholes. In the southern corner and in one third of the length of the wing eastern façade, there were arcades leading to small danskers, in the form of porches based on the zwinger wall.

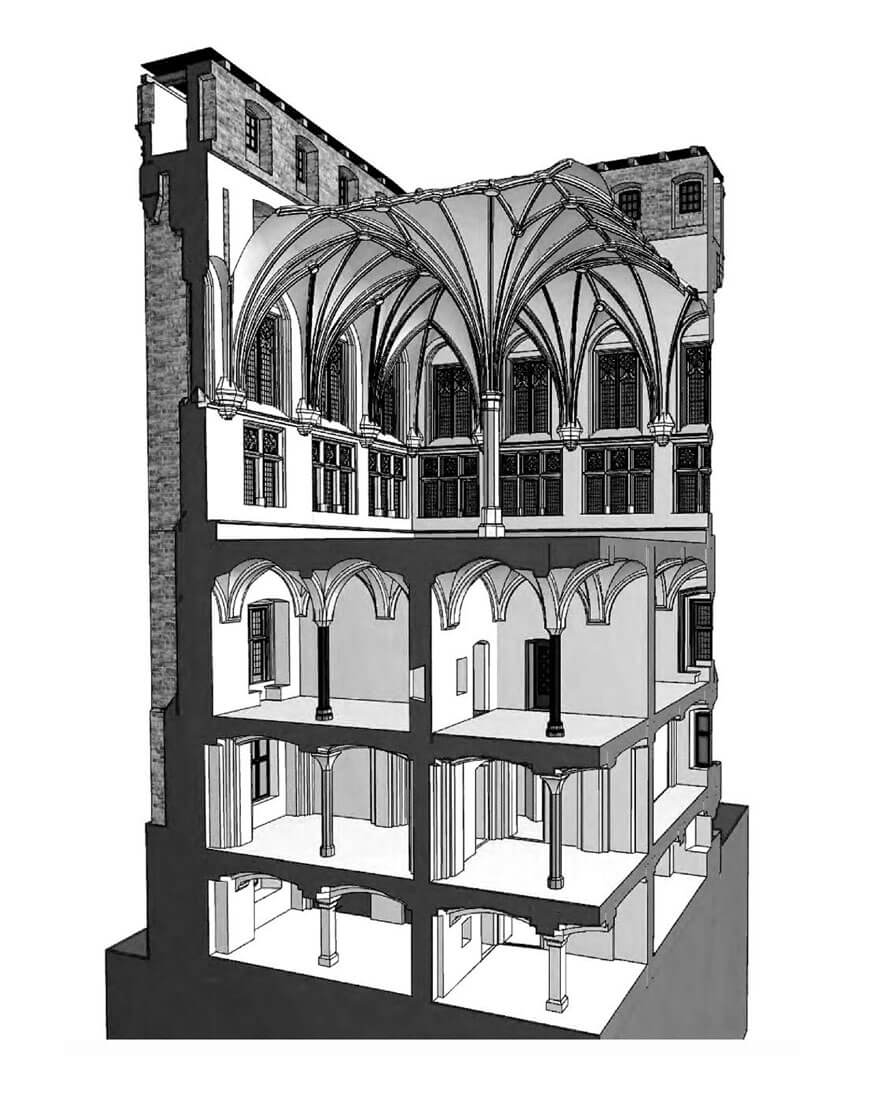

In the 1380s, the Palace of the Grand Masters was expanded, as a result of which it became one of the most impressive secular late Gothic buildings in Europe. It got the form of a tower house with richly decorated facades, protruding from both sides in front of the western wing of the middle castle, using the high riverside slope in the west. On that side, four floors and a mezzanine above the central part were created, while on the eastern side there were two floors above the basements left from the older buildings. The external facades of the palace received rich decoration, originally much better exposed because the original roof was more recessed and lower. The walls were supported by buttresses, between which there were deep, segmental niches. They included large four-sided, segmental headed and stepped formed windows with tracery. Some of the buttresses were interrupted halfway up to insert slender octagonal pillars. On the courtyard side, the pillars above the buttresses were equipped with capitals decorated with bas-relief motifs of a dragon, a hybrid, an unicorn, a monkey or copulating dogs, which could have come from the first palace. The upper part of the palace was topped with a decorative battlement ornamented with panels with blind tracery, and two bartizans in the western corners, mounted on decorative stepped corbels. The external facades of the palace were probably plastered and whitewashed. In this way, the residence stood out optically from the remaining brick buildings of the castle.

Together with the palace, the private chapel of the Great Masters was rebuilt, henceforth dedicated to St. Catherine. Probably for aesthetic reasons, its polygonal apse was removed, and in its place the single-bay building was ended with a straight wall topped with a Gothic gable. Inside, the way the space was used was changed by abolishing the division into two floors (the lower one stopped serving a sacral function). The floor level was also raised by 1 meter, adapted to the new height of the palace rooms, and the main pointed-arch portal in the southern wall was inserted. The former cross-rib vault was replaced with a stellar, four-armed one, and the lighting was provided by three lancet windows, filled with stone tracery and colorful stained glass, the middle of which was set slightly higher than the side ones. Therefore, the chapel lost its prominent location from the outside and was subordinated to the new façade of the palace from the courtyard side. This may have been related to the limitation of the representative and public functions of this sacral space in favor of its more private character, as part of the Great Master’s apartment. On the other hand, the chapel gained importance as a place to store the relics of Saint Catherine, which visitors to the palace could see through the grate in the southern portal.

The Palace of the Grand Masters was accessible from the outside through numerous entrances. Each floor had one or several separate portals, almost all of them leading from the courtyard level of the middle ward. There was no central, more impressive main entrance, instead of which a dispersed communication system was introduced with entrances intended for various purposes and specific groups of people: Grand Masters, main dignitaries, guests, office or kitchen workers. Internal passages and stairs led them to the sets of intended rooms. The communication system was complemented by two staircases that led from the basement up. Food and drinks, as well as letters, could be delivered through service routes hidden in the thickness of the walls, from the working space in the lower part of the palace to the residential and representative rooms above. The most important dignitaries, headed by the Grand Master, went upstairs via wide stairs. They could be accessed through two very simply shaped portals in the lower floor of the chapel.

The interior of the Palace of the Grand Masters was constructed hierarchically, both horizontally and vertically. From the bottom up, as well as from the east to the west, the floors were made higher and higher, and the decorative equipment of individual rooms systematically became richer. In this way vault pillars, portals, windows, capitals and consoles were created. The palace was also characterized by an exceptionally high level of living comfort. Almost all rooms on the three upper floors were heated with warm air from a hypocaustum furnace or with tiled stoves, large windows created brightly lit rooms, and the central latrine shaft ensured hygiene in everyday life. There was also a washroom in the main passage of each floor. Despite the architectural diversity, the palace retained typological and stylistic unity, especially in the western, tower-like part, where the general scheme of interior division was preserved.

The lowest floor of the palace was occupied by the chambers of scribes and other minor officials. Above there were offices, scriptoria, archives and the living room of the chaplain in charge of the chancellery. These rooms were accessible from the main vestibule, where there was also a latrine and a well, which served all the first three floors via shafts. Characteristically, the four office rooms in the western part of the building were accessible only through one portal for security reasons. The office space had a separate entrance from the courtyard and was therefore separated from the two upper levels. Direct communication with the upper floors was via a narrow spiral staircase, through which scribes could bring documents needed during meetings held in the representative rooms. The ground floor of the palace, i.e. the third floor counting from the bottom, served exclusively for residential purposes for high and lower Teutonic officials. Each apartment of a high dignitary in the western part consisted of a heated living room and an unheated bedroom, all covered with rib vaults based on central, octagonal pillars and accessible through richly decorated portals. They could be reached from the main vestibule with an east-west axis, from which a branch led to the centrally located latrine, serving all residents of the ground floor. Moreover, one of the four dignitaries’ rooms was connected to a passage in the thickness of the wall, from which a narrow spiral staircase led to the floor below inside the southern buttress. From there it was possible to go outside through a postern, perhaps created in case an escape was necessary. The north-eastern room of high dignitaries had access to another passage in the thickness of the wall, ended in the south with a narrow, closed chamber, perhaps a treasury or a kind of hiding place. The central part of the palace was occupied by a hall with a vault based on three pillars and a single-pillar chamber, both heated by the hypocaustum system. In the northern part of the ground floor of the palace, minor dignitaries had one bedroom each, but they both had only one common living room at their disposal. In the south-eastern part of the ground floor there were four further rooms, which were probably intended for the guests of the Grand Master. The first floor of the palace housed waiting rooms for guests and large representative rooms in the south (Summer Refectory, Winter Refectory, corner hall), as well as the Grand Master’s living quarters in the northern part. These parts were separated by a communication route consisting of the Low Vestibule on a square plan and the elongated High (Great) Vestibule.

The High Vestibule consisted of six bays with a cross-rib vault and was characterized by buttresses pulled into the interior, replaced almost along the entire height by octagonal, free-standing pillars, connected to the wall in two-thirds of the height by stone connectors. Buttresses with pillars repeated the division of the external façade, only the column above the lavatory was treated differently, which was supported on a console. A lavatory with stone washing bowls and stone seats provided the opportunity to prepare before entering the refectory. A deep recess was created in the thickness of the wall for the portal to the Summer Refectory, flanked by octagonal pillars and filled with side seats, above which the walls were decorated with blind tracery. There was a balcony built above the recess, perhaps intended for musicians entertaining the waiting guests. Moreover, in the thickness of the wall between the High Vestibule and the refectories, passages for servants were hidden, with special counters from which food and drinks were served to the tables of Teutonic dignitaries and their guests. All main rooms could be supplied from the servants’ passage, it was also connected to the lower floors and the attic by two spiral staircases, and was invisible to guests. An especially interesting solution was the intersection of the servants’ passage with the portal to the Winter Refectory. If the latter was used, the two side doors to the servants’ passage were closed and the door to the refectory was opened. This allowed entry from the High Vestibule, while service took place through an opening in the wall on the eastern side. However, if the meeting took place in the Summer Refectory, the two doors to the Winter Refectory were closed and a passage was opened for the servants, who in both cases remained hidden.

The Summer Refectory, occupying the uppermost part of the palace towards the river, was designed on a square plan with sides 14 meters long and 9.7 meters high. It was covered with a magnificent vault resting on a slender octagonal pillar. From the technical side, the vault was actually four barrels, the guiding ribs of which formed a square measuring 7 x 7 meters, limited from the outside by pointed lunettes. Large windows covered the area of three walls, on which they were arranged in two rows, thanks to which the room was flooded with sunlight. The refectory facades originally did not have any paintings, they were only covered with red, while the white vault was decorated with painted plant twigs. There was a fireplace on the eastern wall of the Summer Refectory, although it rather played a decorative or auxiliary role, as it was insufficient to heat the room due to the large windows. Next to it, there was a wide opening for serving drinks and food, accessible from the servants’ passage in the thickness of the wall, which could be closed with a wooden hatch or with a curtain.

The Winter Refectory, lower and smaller one, was heated with warm air from the hypocaustum furnace, so it could be used all year round. It had dimensions of 12 x 12 meters and a height of 7.8 meters, with a vault analogous, although slightly more modest than in the Summer Refectory. The central pillar did not receive a capital, but was placed on a polygonal base and a plinth. The walls were covered with paintings created after 1400, depicting portraits of Great Masters. There were holes in the floor between the tiles, closed with covers, through which air heated in the furnace could enter. From the east, the Winter Refectory was originally adjacent to two rectangular rooms with barrel vaults. One of these may have been the Council Chamber, a small area intended for internal and confidential meetings of a small group of people. A slightly hidden and protected from eavesdropping location would correspond to this function. Next to it there was a corridor connected to the servants’ passage and the Low Vestibule, as well as to a large hall located in the corner of the building. The latter was probably a waiting room for the Grand Master’s guests, equipped with wall benches. It was heated by a hypocaustum furnace and a fireplace, and was covered with a vault supported by two octagonal pillars.

The part of the palace intended as the Grand Master’s private residence consisted of several rooms: a living room, a bedroom with an adjacent latrine and a small office, supplemented by the private chapel mentioned above, probably separated by a half-timbered wall. The Great Master’s living quarters attracted attention with their rather simple interior architecture, partly resulting from the need to adapt to older buildings, subordinated to functionality rather than lavishness. The most important thing was the optimal connection with the representative halls, so that the Grand Master did not have to travel long distances. The Grand Master’s chambers were also distinguished from the living quarters of other dignitaries by their general large area, as well as wall paintings filling all the interiors with decorative motifs (illusionistic curtains on a red background) and religious motifs (a group of four holy women in the office room). The ribs of the vaults were accentuated with red and orange stripes, while the vault itself were covered with a painted ornament in the form of a plant twig.

The lower ward had a shape similar to a rectangle with dimensions of 140 x 270 meters, and additionally, as mentioned above, its fortifications were extended to the south, thanks to which it covered the middle and upper wards from the east and west. The lower ward served as an economic and storage base, after the bailey in the middle ward was expanded and adapted for residential and representative functions. Its buildings were generally arranged in four rows on the north-south axis. The entrance was from the west through the gate of St. Laurentius, located next to the moat of the middle ward, and the opposite Woodcarving Gate, flanked by two towers (Vogt’s Tower and Thesaurarius’ Tower). In addition, there was a northern gate at the corner of the fortifications, bricked up in 1457 to commemorate the triumphal entry of King Kazimierz IV. Near the south-west corner of the castle complex there was the Shoemaker’s Gate, and from the west, at the height of the upper ward, there was the Bridge Gate, together with the adjacent zwinger area in the Middle Ages included into the area of the lower ward. Behind it, in the transverse wall, there was the St. Nicholas Gate, controlling traffic between the town and the northern part of the lower ward. The area near the river between the middle and lower wards, located between two lines of walls, was filled up and formed a kind of causeway along the road from the Bridge Gate towards the gate at the church of St. Laurentius.

In the first half of the 14th century, the area of the bailey (lower ward) was surrounded by a moat and brick fortifications, consisting of two series of walls, with a number of towers in the inner line. The north-west corner was occupied by the Maślankowa Tower, which according to documents housed a prison. It was built on a circular plan with a diameter of 8.7 meters, with a height of less than 29 meters and a wall thickness of 2.6 meters. Its upper part was extended through three-order moulding. Next to the Maślankowa Tower there was Kęsa Tower, partially demolished in the 15th century. In the northern section of the walls there was also an octagonal Clock Tower, distinguished by the clock hung on it in 1401. The north-eastern corner was defended by the Szarysz Tower, also octagonal. In the eastern line of the defensive wall there was a Three-wall tower on a square plan with chamfered corners, further south, a four-sided Powder Tower, securing a small postern to a watering hole for horses. Next was the four-sided Vogt’s Tower with sides 7.1 meters long and the more impressive Thesaurarius’ Tower with sides 11.5 meters long. The latter must have had residential functions, because its ground floor was covered with a stellar vault. The southern part of the eastern section was defended by five towers, the corner one of which was octagonal. Behind it, the wall ran towards the river, surrounding the moat in front of the outer wall of the upper ward’s zwinger, and in the south-west corner it was reinforced with a 15th-century tower flanking the entrance to the town (Shoemaker’s Gate). The western section of the walls at the level of the upper ward was reinforced by a pair of semicircular towers, between which there was a Bridge Gate, facing the bridge over the Nogat. The Bridge Gate had two pointed portals, separated by a buttress on which a round bartizan was suspended using squinches. The interior of the towers was divided into three floors, connected by a spiral staircase in the thickness of the walls. A wooden bridge across the river was protected by the fortified bridgehead.

After the great Polish-Teutonic war, in the years 1411-1413, the lower ward was reinforced from the north and east with new earth fortifications called Plauen’s Rampart. In the second stage of expansion, around 1418, an eastern gate complex was created at the Mill Canal, called the New Gate, and on the northern side, next to the Maślankowa Tower, a foregate and a cylindrical tower with a large diameter were built, adapted to the use of firearms. The New Gate was protected by a similar cylindrical, massive tower with a vaulted room on the ground floor. In the years 1441-1448, Plauen’s Rampart was modernized with a brick wall with a covered wall-walk and six semicircular and cylindrical towers open from the inside.

In the years 1300-1320 a coach house was built, the so-called Karwan. It was a two-story building with dimensions of 20 x 45 meters, covered with a gable roof supported by gables decorated with blendes, with entrance portals from the north and west. The interior of the coach house was single-space on the ground floor, with rooms for carts separated on both sides by transverse screens. Each of these rooms was covered with a barrel vault, lit by a pair of pointed windows and opened with a semicircular arch. On the first floor there were warehouses, loop holes and passages to the walks in the crown of the defensive walls. On the north side of the coach house was the house of the its master. Both buildings were part of the small courtyard separated from the lower ward, where there were also four stables, five barns and a watering hole located outside the perimeter of the walls. On the southern side of the coach house, also next to the defensive wall, there was a rectangular house with craftsmen’s apartments.

In the first half of the 14th century, buildings were also erected inside the lower ward, including a building over 142 meters long by the wall stretching over the extension of the moat of the upper and middle ward. There were living quarters and an infirmary for servants, a brewery, a bakery, a malt house, a kitchen and, at the end, an aisleless church of St. Laurentius together with the adjacent gate of the same name. In the western part of the lower ward, on the Nogat, a monumental, four-story granary was built. There were stables along the northern curtain. The interior of the spacious courtyard was also occupied by workshops, forges, foundry, warehouses and a small water tank.

Current state

The Malbork castle is considered one of the largest in the world and at the same time one of the most remarkable works of defense and residential construction in medieval Europe. Palace of Grand Masters on the middle ward is one of the most outstanding achievements of the European secular Gothic. The castle is also a monument showing the development of conservation thought, from the early nineteenth century to modern times. Since 1961, it has been the seat of a museum, and in 1997 it has been added to the UNESCO World Heritage List. Today, the huge castle museum presents reconstructions of historical interiors, exhibitions related to the history of the object, military, archaeological finds and collections of minerals, not to mention temporary exhibitions. Three, four hours is the absolute minimum you need to book for sightseeing. You can find out about dates, prices and opening hours on the official website of the museum here.

Unfortunately, due to turbulent history, today’s castle has lost much of its original architectural substance, reconstructed in the 19th century. The cloisters of the upper ward date from 1881-1893, (only the granite column, three pillars in the north-east corner and single vault corbels are original). The facades from the courtyard side had to be renewed, the foregate of the upper ward was built at the end of the 19th century on the original foundations, as the well and most of the rooms in the upper ward (e.g. the refectory in the northern wing, which architectural details of the vaults and paintings, except for the corbels, were recreated arbitrarily, and the inscription at the door was taken from the chapter house of the Hospitaller’s Castle of Margat in Syria). Of the corner turrets of the upper ward only the north-west one is original. From the 19th century it also comes upper part of the large dansker tower, the mill in the upper ward’s zwinger, the Sparrow’s Tower with the porter’s house and the Klesza Tower with the so-called Bell Ringer House (rebuilt in an acceptable form, but not in the right place). The effect of the 19th-century reconstruction is a large part of the buildings of the middle ward (with the exception of the Palace of the Grand Masters and the impressive gable of the infirmary). From the foundations Conrad Steinbrecht rebuilt the polygonal chancel of the chapel of St. Catherine, unfortunately destroying the late Gothic chancel with a straight closure. At the beginning of the 20th century, the Vogt’s Tower and a large part of the buildings of the lower ward were reconstructed and renewed.

After the enormous destruction of World War II, the eastern gable of the upper ward was unfortunately rebuilt in a simplified form. The four floors of the main tower had to be rebuilt, which were still original until the bombing. In addition the chapel of St. Anna and the church of the Blessed Virgin Mary in the upper ward were reconstructed, but the reconstruction of the wimpergs and pinnacles of the latter was abandoned, as a correction of the 19th-century actions of Conrad Steinbrecht. As the greatest damage was caused by artillery fire in the eastern part of the castle, the eastern wing of the middle ward had to be rebuilt along with almost the entire church of St. Bartholomew. In the years 2014-2016, the symbol of the castle, the figure of Mary with the Child on the external façade of the church of the upper ward was reconstructed, in which approximately 70% of the material consisted of original fragments found after the war (the original right hand of the sculpture is preserved in the museum). By 2016, the New Gate complex was also rebuilt, which was first reconstructed in the 19th century by German researchers.

bibliography:

Architektura gotycka w Polsce, red. M.Arszyński, T.Mroczko, Warszawa 1995.

Herrmann C., Der Hochmeisterpalast auf der Marienburg. Konzeption, Bau und Nutzung der modernsten europäischen Fürstenresidenz um 1400, Petersberg 2019.

Herrmann C., Der Hochmeisterpalast auf der Marienburg. Rekonstruktionsversuch der Raumfunktionen [w:] Magister operis. Beiträge zur mittelalterlichen Architektur Europas, Regensburg 2008.

Herrmann C., Die Hochmeisterkapelle auf der Marienburg [w:] Castrum sanctae Mariae: die Marienburg als Burg, Residenz und Museum, Göttingen 2019.

Jesionowski B., Prarat M., Najstarsze dzieje budowlane Wieży Kleszej na Zamku Wysokim w Malborku oraz prowadzone tam prace konserwatorskie w XIX w. w świetle wyników badań architektonicznych (cz. 1 i 2), “Wiadomości Konserwatorskie”, 54-55/2018.

Juźwiak S., Trupinda J., Krzyżackie zamki komturskie w Prusach, Toruń 2012.

Leksykon zamków w Polsce, red. L.Kajzer, Warszawa 2003.

Garniec M., Garniec-Jackiewicz M., Zamki państwa krzyżackiego w dawnych Prusach, Olsztyn 2006.

Torbus T., Zamki konwentualne państwa krzyżackiego w Prusach, część II, katalog, Gdańsk 2023.

Wasik B., Zachodnie międzymurze zamku w Malborku w świetle badań archeologicznych z 2020 roku. Przekształcenia topografii i zabudowy, “Ochrona Zabytków”, 1/2021.