History

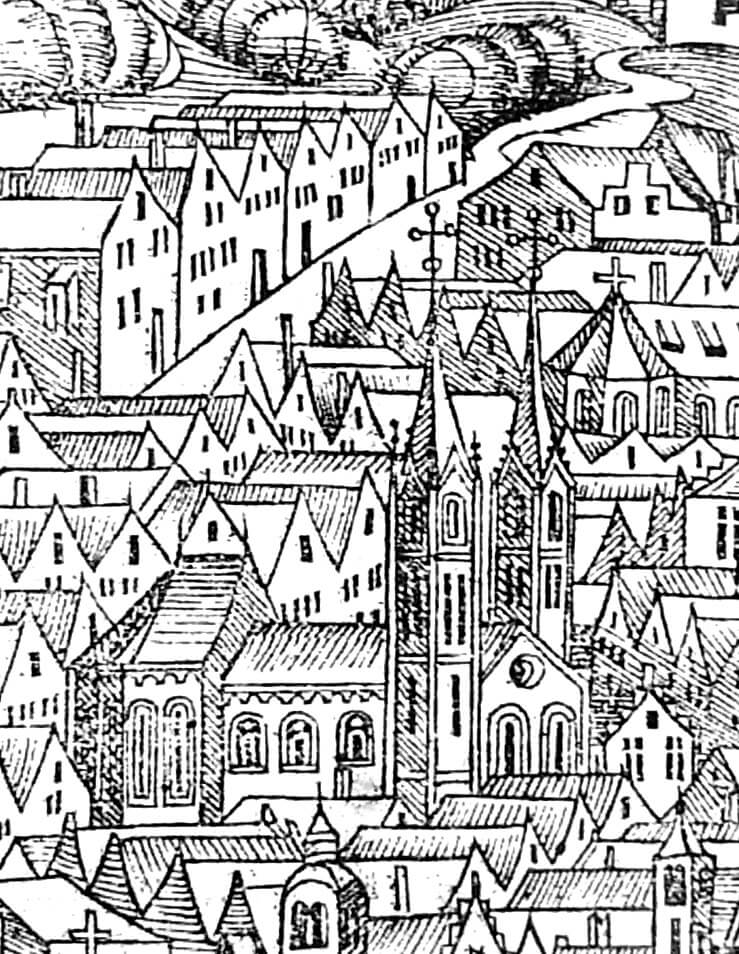

The original, Romanesque church of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary was built at the beginning of the 13th century or at the latest in the 20s of the 13th century from the foundation of bishop Iwon Odrowąż. In 1224, its parson Stefan was mentioned in written sources, and in 1248 a certain Peter. At that time, the church was already a parish temple, because the church of Holy Trinity was given to the Dominicans. Most likely the Romanesque church was destroyed or damaged during the Mongol invasion of 1241, subsequent devastations could also affect it during the next Tatar invasions of 1259 and 1287.

The construction of the Gothic church of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary began around 1290, and the two-tower hall was consecrated around 1320. This was confirmed a year later by a document of the Orthodox Patriarch of Alexandria, Idzi, who gave an indulgence to all those who will visit the church on the anniversary of the consecration. Finishing works, however, continued until the end of the 1330s. Probably the end of the construction could be associated a giving of the title of archpriest to the parish priest in 1238, which was an honorable distinction and raised his rank.

In the years 1355-1365, thanks to the foundation of a wealthy burgher and trusted courtier of King Casimir the Great, Nicholas Wierzynek, an elongated chancel was erected. Then, as a result of the reconstruction from the end of the fourteenth century, St. Mary’s Church from the hall was transformed into a basilica. It is known that in 1392 a new floor was laid, in 1393 lead was brought to cover the roof, in 1394 mason Henry received payment for the demolition of part of the old walls. In the same year, building materials for new vaults were also prepared. The central nave was vaulted in 1397 by architect Nicholas Werner.

In the first years of the 15th century, the north tower was raised, which in 1478 was covered by Matthias Heringh (Heringk) with a richly decorated late-Gothic helmet. A little earlier, in the years 1435 – 1446, chapels were attached to the aisles. They belonged to the rich families of Kraków, they were also cared by guilds. Their builder may have been master Francis Wiechoń with whom in 1335 a contract was concluded for the construction of the chapel of St. John of Nepomuk.

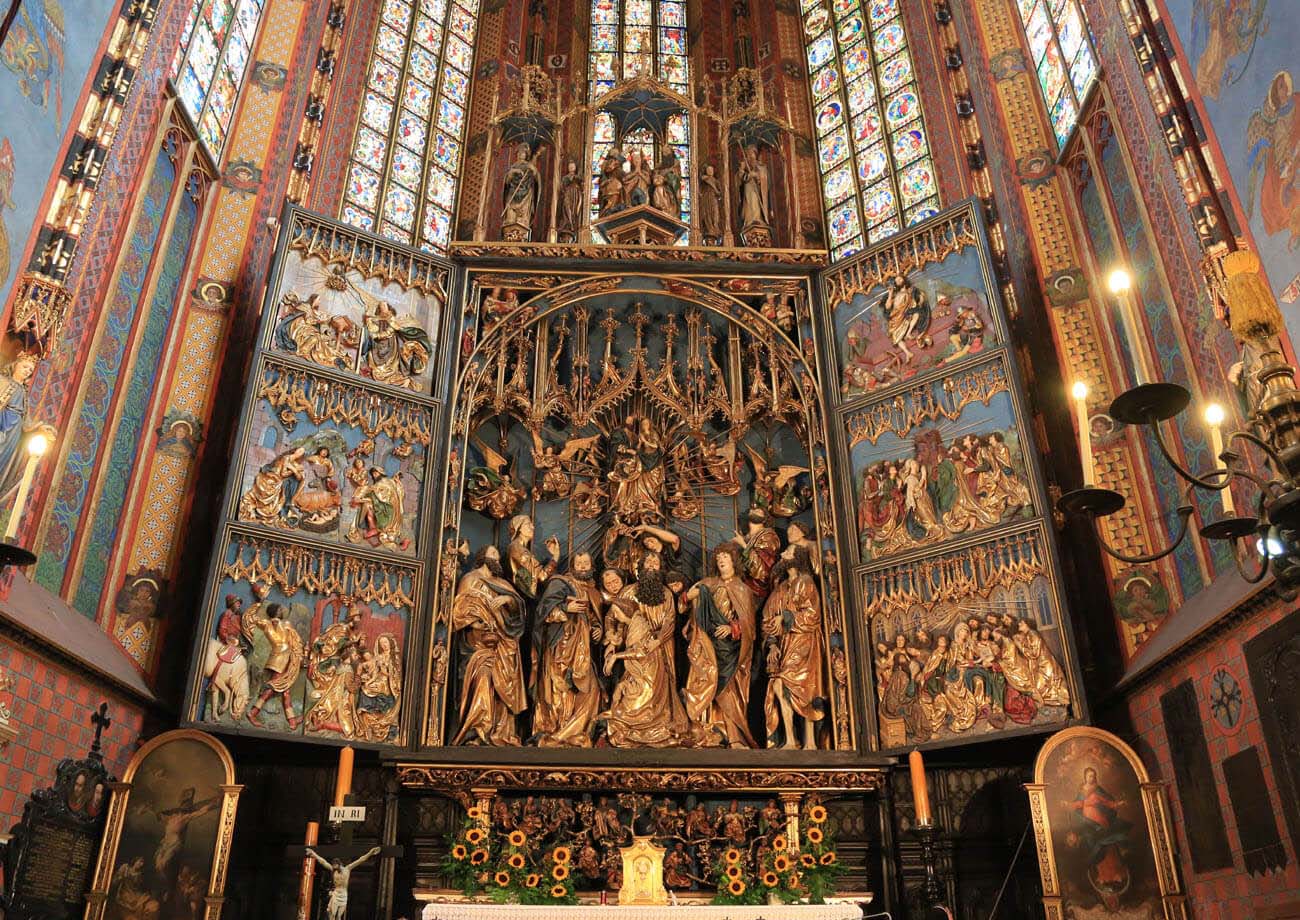

In 1442, an earthquake took place that caused the chancel vault to collapse, which also destroyed the 14th-century high altar. The first one was quickly rebuilt by mason Czipser, while the church had to wait a bit longer for the new main altar. It was only after 30 years that the Kraków councilors decided to erect an impressive altar, worthy of the parish of the royal city. The master for its construction was sought in Nuremberg with whom Kraków’s inhabitants had economic ties. A young, promising artist, Veit Stoss was chosen, who arrived in Kraków in 1477, and took 12 years (with breaks) to work on his life’s work. One of the greatest artistic achievements of the late Middle Ages was completed in 1489. He received a considerable sum of 2,808 florins for his work, which was the amount of Kraków’s annual budget at that time.

The Renaissance period did not bring about any major changes in the architecture of the church, it was only renovated by Hieronim Powodowski in 1585-1586, and new equipment was added inside, especially epitaph plaques. As in the Middle Ages, the temple was still under the protection of the city council, all major city ceremonies were held there, and preachers were also heard here. Initially, sermons were preached in German, which was due to the predominance of German nationality among patricians. It was not until 1536 that members of the parliament assembled and asked King Sigismund I the Old that the sermons in St. Mary’s Church should be preached in Polish and that the German-language liturgy would be moved to the nearby church of St. Barbara.

In the 17th and 18th centuries interior of the church was changed to the Baroque one, among others the walls were decorated with polychrome made by Andrzej Radwański. In the years 1750-1753 a mismatched Baroque porch was attached to the church facade and at the end of the 18th century, the church cemetery that was used since the Middle Ages was removed. In the nineteenth century, however, began the first thorough renovation of the building, carried out in the years 1889-1891. Thanks to it, many Baroque accretions were removed, new polychromes that harmonized well with Gothic architecture were made by Jan Matejko, and stained glasses were embedded in the windows by Stanisław Wyspiański and Józef Mehoffer.

Architecture

The Gothic church of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary was erected in the north-eastern part of Kraków’s market square, as a structure orientated towards the sides of world on the east-west line, and thus situated at an angle to the market square. It was built on the foundations of an earlier, Romanesque temple, which also explains its asymmetrical orientation, because the first church was built before the foundation of the city. It was a three-aisle structure 42 meters long and 24 meters wide, with two western towers located on the extension of the side aisles. Perhaps the Romanesque church had a transept, but the appearance of the chancel is unknown. Originally, it was surrounded by a cemetery, and a jougs was installed at the western entrance, i.e. the ring of penitents, which was formerly put on the heads of sinners, at such a height that the condemned man could neither straighten or kneel.

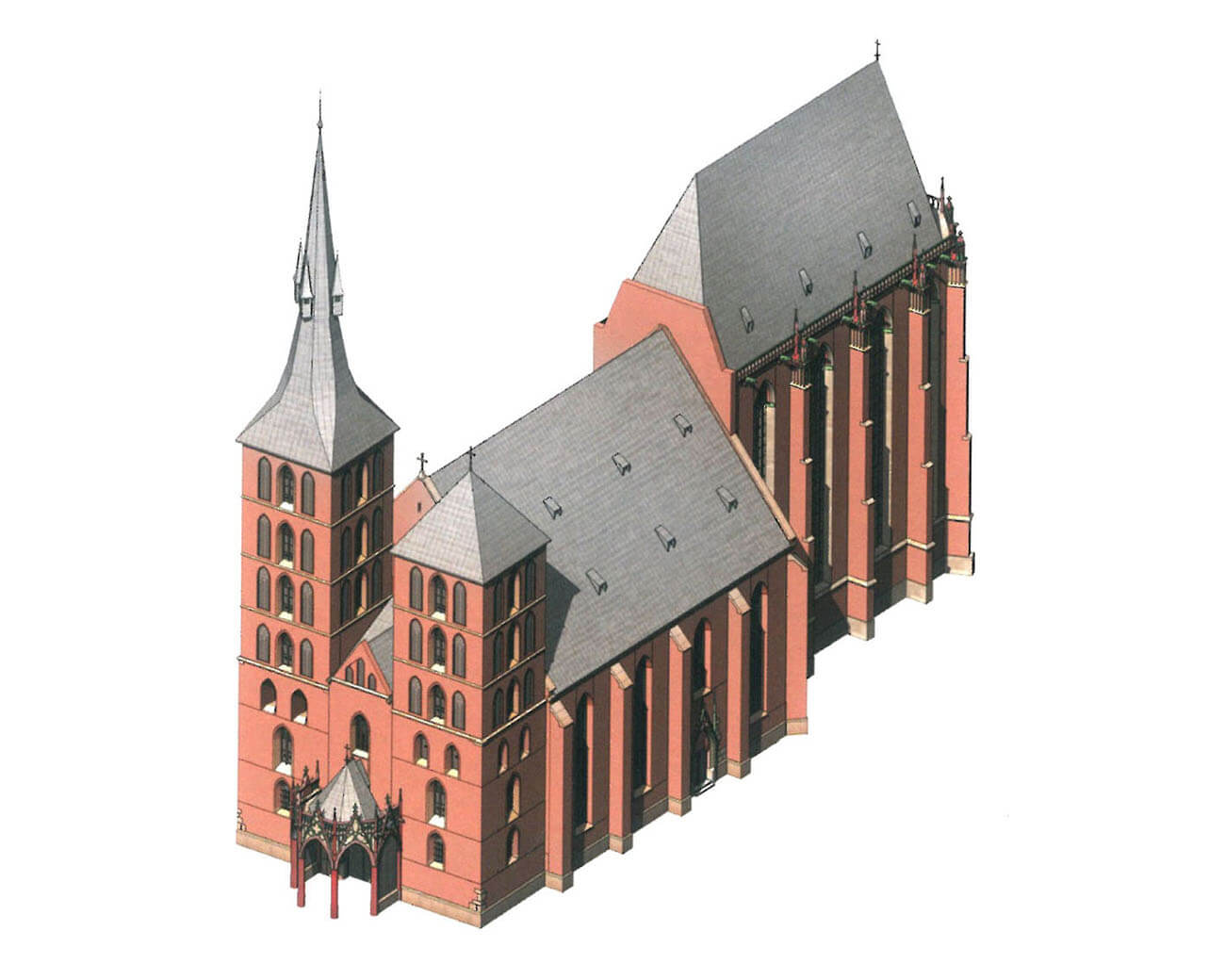

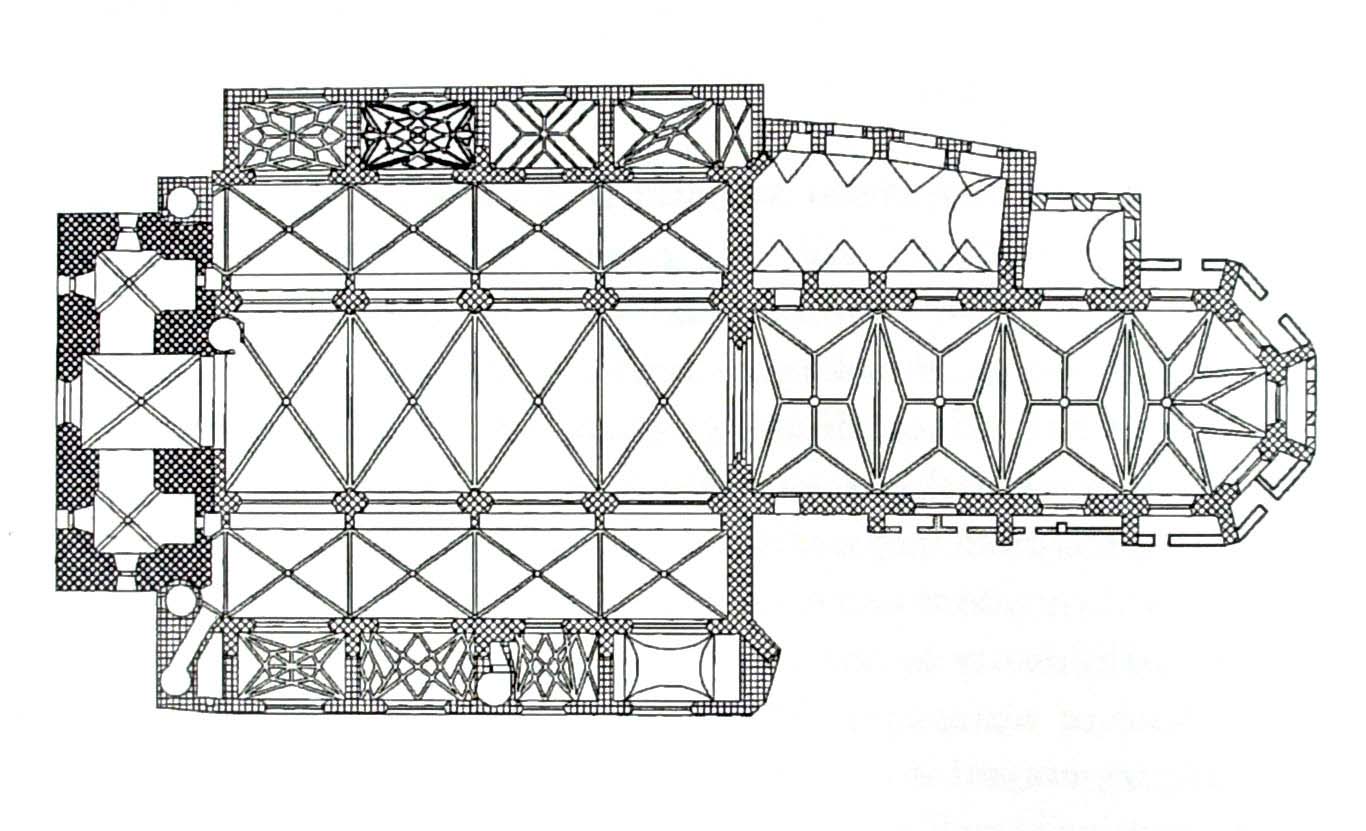

Originally, the church was a hall building with two low, four-sided towers on the west side. In the years 1355-1365, a three-bay long, polygonal ended from the east chancel was built, and in the last decade of the fourteenth century the church from the hall was transformed into a basilica, by raising the central nave and equipping it with clerestory windows to illuminate the interior. The towers were systematically raised from the second half of the fourteenth century to the first half of the fifteenth century. The brick walls were erected in the monk and Flemish bonds, the external facades were diversified with regularly spaced putlog holes on the scaffolding used during the construction, and in some places they were decorated with patterns made of black-colored zendrówka bricks. Architectural details were made of limestone and sandstone ashlar.

Eventually, St. Mary’s Church reached the form of a three-aisle basilica with a two-tower western facade, a wide nave obtained thanks to aisles and chapels built in the years 1435 – 1446 from the north and south. Originally, its characteristic element were the flying buttresses, distributing the expansion forces of the vaults, mounted above the roofs of the aisles and growing out of the roofs of later added chapels (in the early modern period they were covered with higher roofs of aisles). The slender and soaring chancel was finished on three sides from the east and equipped with narrow windows pierced between high, stepped buttresses. A sacristy was attached to it in the 15th century from the north.

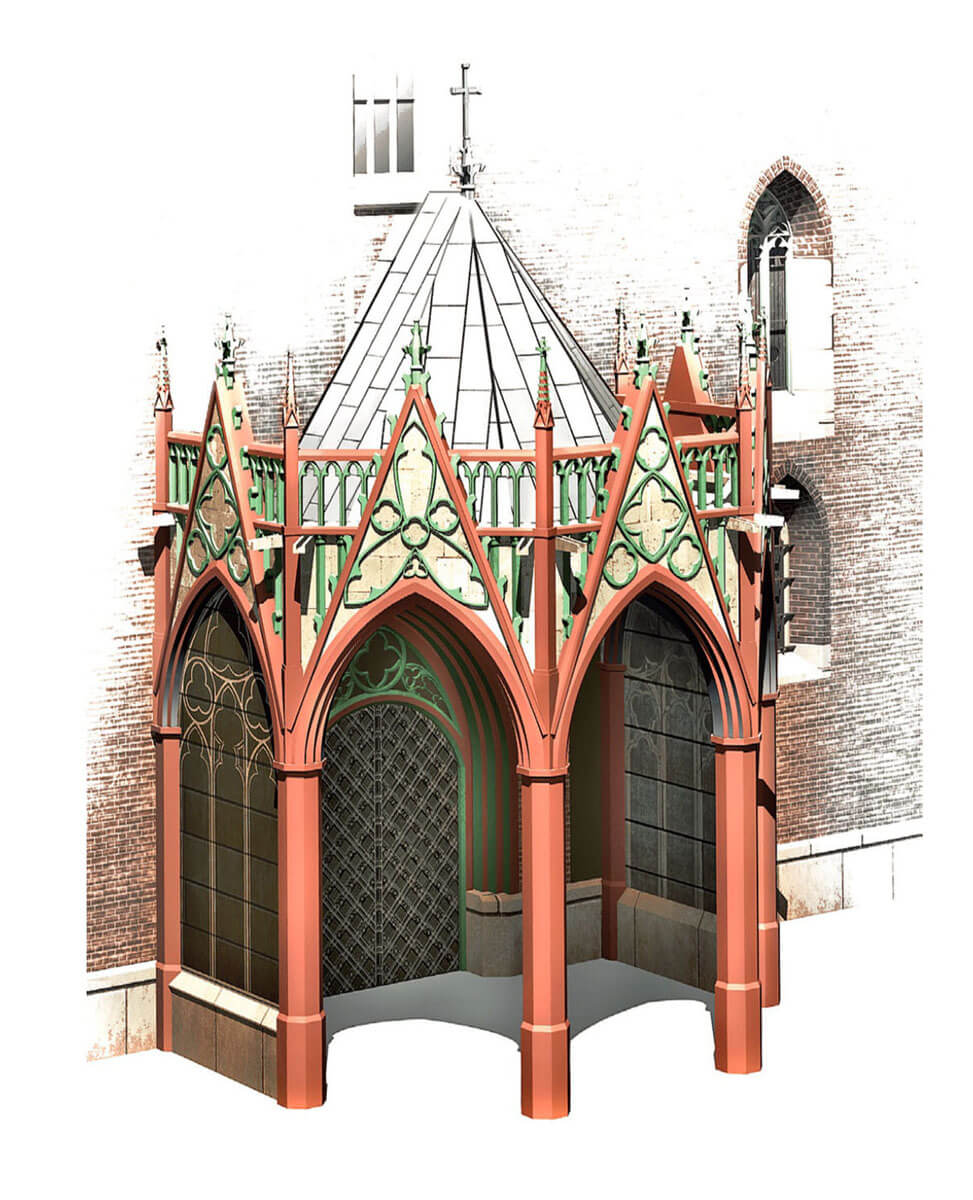

The church, especially its chancel, received extensive architectural decorations: carefully made three-light windows with tracery, floral friezes, richly decorated pinnacles on buttresses, and sculptural consoles with representations of animals and people. The latter in number 21 were set around 1390 at the cornice crowning the chancel. The top parts of eleven windows contained about 40 figures, animal images and performances of a fantastic character, complemented by rich floral decoration. Even richer decorations were found in the niches of the windows at the base of the arches (both inside and outside). There you can find 44 friezes made of leaves, and the stone shafts separating the windows are crowned with 22 miniature capitals decorated by leaves. Probably stonemasons working at the chancel of St. Mary’s Church were educated in the construction of the choir of the church of St. Stephen’s in Vienna (around 1304-1340).

The front of the basilica is distinguished by two towers of different heights. The higher, northern one, called Hejnalica was the town’s property in the Middle Ages. It finally received 81 meters in height. It was built on a square plan, but at the height of the ninth floor it goes into an octagon, pierced with pointed arches, housing two floors of windows. The octagonal part was bricked up in the years 1400-1408 and probably it was related with the desire to raise the tower above other buildings in the city. There was a guard room at the top of the tower, hence the bugle call, i.e. a signal about the constant watch over the city’s security was heard. In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries it was trumpeted twice, only at dawn and at sunset. The tower was covered by a late Gothic helmet, which was the work of master Matias Heringkan from 1478. It had the form of an eight-pointed star with an octagonal spire surrounded by a wreath of eight turrets. Each of them consists of two floors separated by a cornice, and all of them are crowned with golden balls. The shape of the helmet is completely individual and it is difficult to find sources of inspiration for its creation. At the tower on the north side there is a Gothic annex with stone spiral stairs.

The lower southern tower, 69 meters high, was intended for the church belfry. Erected on a square plan, it received a distinct storey division, marked along its entire height with cornices and steps, thanks to which it narrow upwards. Like the north tower, the south tower had one window on each free side of the two lowest storeys, and two windows on the third storey. From the fourth floor up, it was decorated on each free side with central windows, which were flanked with blendes of a similar, pointed form. In the Middle Ages, these blendes could be covered with paintings with tracery motifs. The windows were deep splayed and had rich traceries.

The entrance to the church led through the side porches at the height of the third bays from the west. Both the portals to the porches and the portals from the porch to the aisles received pointed, moulded jambs. The outer ones were flanked with bas-relief pinnacles and framed with bent drip cornices, and their outer archivolts were formed in ogee arches with crockets on the edges and fleurons on the finials. The main entrance was created from the west, from the side of the market square, where it was preceded by a Gothic, polygonal porch open to the outside with pointed arcades.

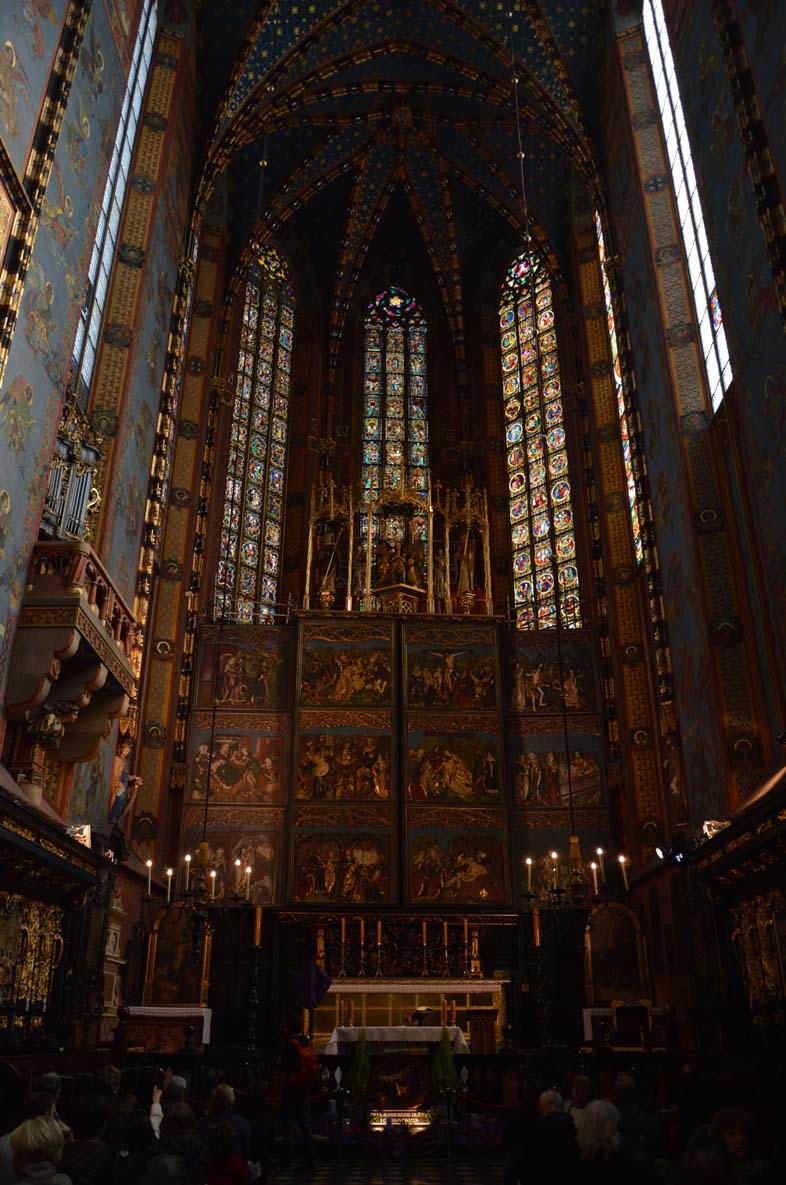

The interior of the chancel was covered with a stellar vault, made in 1442. Its ribs were fastened with stone bosses in the shape of the coats of arms of Poland, Kraków and Bishop Iwon Odrowąż and lowered towards the floor in wall shafts interrupted by canopy niches, where six stone statues of the prophets were placed. The asymmetry of the chancel windows is striking, because in the southern wall and in the apse they go down quite low, while on the northern wall they end much higher. There, under the cornice cutting them off, the wall surface was varied with slim, ogival recesses of equal height (three in each bay), filled with blind traceries with characteristic radial arrangements with multiple toes.

The four-bay central nave, 28 meters high, was covered with a cross-rib vault, as were the lower aisles. The central nave ribs were supported by the shafts, polygonal at the bottom, passing from the bundles above the canopy niches above the cornice and inter-nave arcades. In the side aisles, the bases of the vaults are embedded in the buttresses of the pillars, and on the perimeter walls there are supported canopies of figural niches. At the beginning of the 16th century, the interiors of six chapels were rebuilt and new vaults were built in them. Among them stood the chapel of St. Laurentius (north one, second from the west) with skew ribs, popularized by the famous from Prague architect Benedikt Ried and a group of late Gothic traceries filling the chapels of St. John (north one, first from the west), St. Laurentius and Lazarus (southern, first from the west).

In the eastern part of the chancel there is the main altar, a woodcarving masterpiece from the second half of the 15th century. It received dimensions of 11 x 13 meters, consisting of a centrally located, spacious “wardrobe” based on a predella (base of the altar), two pairs of side wings and an openwork finial. The construction was made of hard oak wood, while the sculptures were made of softer linden wood. The width of the entire chancel was adopted as the base of the altar, and that after closing the movable wings the altar did not seem too small in relation to the church, the second wings were added – constantly open, immobile. The predella contained so-called Jesse’s Tree depicting Maria’s pedigree and above it a decorative plant frieze with animals. The composition of the main altar stem was thematically based on the so-called Golden Legend depicting, among others, Maria’s death. The author placed the main stage, i.e. a group of apostles surrounding the mother of Christ, in the deep recess of the wardrobe. The whole composition was framed with an arch featuring figurines of townspeople, merchants, knights, students and craftsmen. The huge figures of central scene, reaching 2.7 meters in height, were cut from one block of wood and given the features of extraordinary realism. Body structure, reproduction of wrinkles, shaping hands, muscle and vein selection are distinguished by the unprecedented knowledge of anatomy and the author’s insightful perceptiveness. All characters were strongly personalized, so it is assumed that their models were real people from the environment of Veit Stoss. Less visible small figures or animal figures were also presented with the same precision.

Current state

St. Mary’s Church is one of the most important churches of Kraków, next to the Wawel Cathedral, and one of the most famous Polish architectural monuments. Although it has retained its Gothic character, several early modern changes have been introduced over the centuries, such as the cupola of the southern tower, the transformed western porch, or chapels embedded between the chancel buttresses. The Gothic chapels have lost their medieval gables, and the western gable between the towers has not survived. The interior underwent baroqueization, and during the regothisation of the nineteenth century, the ribs of the chancel vault were simplified, traceries were partially renewed in the seven windows of the eastern closure and in several chapels. The neo-Gothic ones were installed in several windows of the towers and over the southern porch.

Inside, among the elements of medieval furnishings, there is a late Gothic crucifix from around 1520, placed in a chancel arch, original Gothic stained glasses located in three windows of the eastern apse (eastern closure of the chancel), consisting of 120 parts, and primarily the altar or rather a retabulum made in the years 1477–1489 by the sculptor Wit Stwosz. This is one of the greatest examples of late medieval woodcarving in Europe. In addition, a special turnstile has been preserved in the attic by which the altar was mounted. Unfortunately, this monument is not available for tourists. Visiting the rest of the church takes place every common day from 11.30 to 18.00, and on Sundays and holidays from 14.00 to 18.00. Tickets are available at the ticket office opposite the south aisle.

bibliography:

Architektura gotycka w Polsce, red. M.Arszyński, T.Mroczko, Warszawa 1995.

Bober M., Architektura przedromańska i romańska w Krakowie. Badania i interpretacje, Rzeszów 2008.

Krasnowolski B., Leksykon zabytków architektury Małopolski, Warszawa 2013.

Ludwikowski L., Kościół Mariacki w Krakowie, Warszawa 1982.

Marek M., Cracovia 3d. Rekonstrukcje cyfrowe historycznej zabudowy Krakowa, Kraków 2013.

Rożek M., Kościół Mariacki w Krakowie, Piechowice 1994.

Walczak M., Kościoły gotyckie w Polsce, Kraków 2015.

Węcławowicz T., Fazy budowy kościoła Mariackiego. Modele rekonstrukcyjne dla Muzeum Historycznego Miasta Krakowa, “Krzysztofory” , nr 28, część 2, Kraków 2010.