History

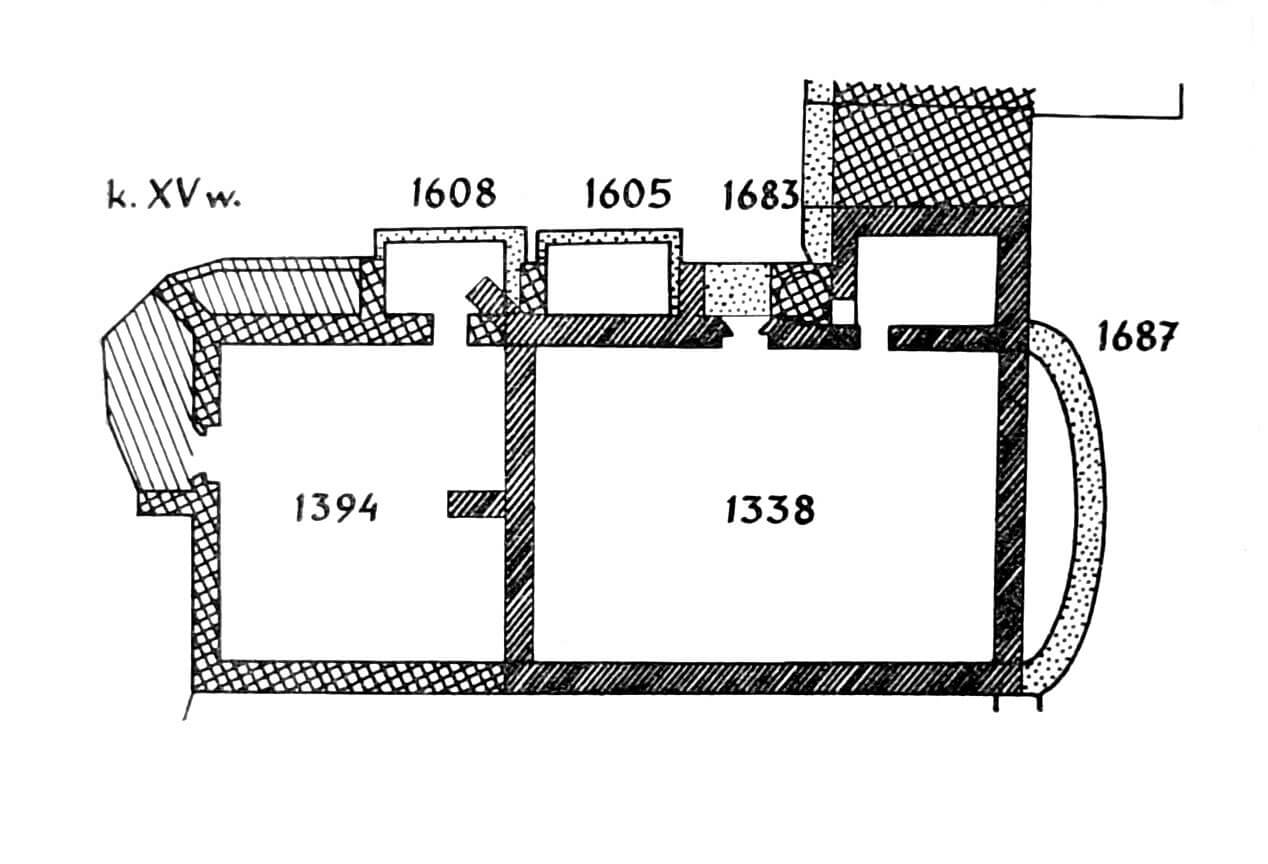

In the first half of the 14th century, Nicholas Wierzynek founded the chapel on the terrain of the later Gothic church of St. Barbara. It was recorded for the first time in 1338, when the Kraków councilors sent a letter to Pope Benedict XII, asking for indulgences for the people visiting this chapel. In 1394, the city council decided to enlarge the original chapel, about which they sent a letter to bishop Piotr Wysz. It was written in it that the councilors bought a square from Paweł, the parish priest of St. Mary’s Church, giving him in return 2/3 of the tenement house located opposite the parish school. The bishop gave permission to erect the church of St. Barbara, provided that the foundation does not harm the Kraków Cathedral and St. Mary’s Church and the sermons in Polish that were held there. At that time, the city council sought the patronage of St. Mary’s Church, which initially belonged to the bishop and the parish. Ultimately, councilors only received patronage over a few altars, but after the deaths of parish priest Paweł and bishop Wysz, Polish sermons were moved from St. Mary’s Church to St. Barbara.

The construction of the church of St. Barbara was mostly completed in 1396, when a certain Petrus Cremator of Argenti donated a cup with a paten for the new building. A year later, Pope Boniface IX granted indulgences to the people visiting the church, but still in 1402 the city paid 20 fines to cover it. Perhaps Nicholas Werner participated in these works, who few years earlier worked on vaults of St. Mary’s Church, and in 1402 was recorded in the city books in connection with dues. In the same year, the burgher Hanko Bartfal endowed the main altar and the altarist at St. Barbara, and Bishop Piotr Wysz approved the foundation. It was also written at that time that the construction was financed mostly by Queen Jadwiga.

In 1404, a Literary Brotherhood was founded at the church, in 1444 it was renamed to Merchant Brotherhood, and in 1449 it was called the Brotherhood of St. Barbara. At the church, there was also a college of mansionaries, i.e. priests who had to sing the office of the Blessed Virgin Mary at a certain time, founded in 1435 by Dietrich Weinrich and enlarged until 1519, when the eighth mansionary was appointed. At the end of the 15th century, a chapel called Gethsemane was built next to the entrance to the church. Work on it probably began around 1488, when Adam Szwarc, a relative of the parish priest from St. Mary’s Church, endowed the altar in a “hortus Domini”. In 1516, bishop Jan Konarski approved the foundation of an altarist at the chapel, so it must have been fully completed at the latest in this period.

In the first half of the 16th century, Polish national self-awareness began to awaken, with the simultaneous process of Polonization of German bourgeois families. For this reason, in 1536, during the session of the Sejm in Kraków, at the request of land deputies and with the consent of senators, King Sigismund I ordered the transfer of Polish sermons to a large St. Mary’s Church, and the German ones to the smaller church of St. Barbara. German-speaking councilors could only refer to the old custom, because the removal of Polish sermons was unlawful in the 15th century. They were also in the minority, because apart from Polish-speaking councillors, the Polish nobility and ordinary townspeople opted for the change.

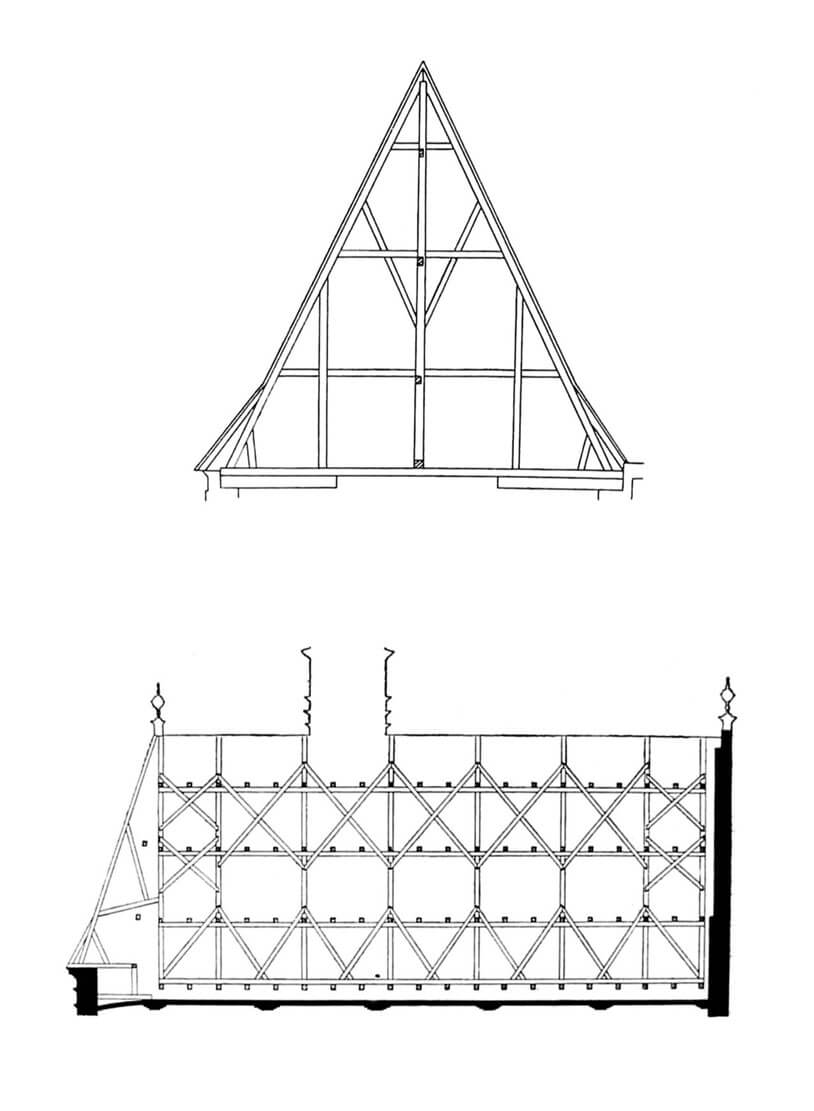

In 1583, the church of St. Barbara was handed over to the Jesuits, although the then papal legate, Antoni Possewin, was not satisfied with such a small building. After the church was taken by the order, the equipment was replaced with Renaissance ones, the walls were whitewashed and a turret was erected on the roof ridge in 1588. Piotr Skarga, a leading Polish representative of the Counter-Reformation, preached in the modernized and renovated church. In 1687, the church was rebuilt by the Jesuit architect Stanisław Solski, who added an apse on the eastern side, raised the interior (while maintaining the Gothic roof truss) and made a new barrel vault. After the dissolution of the Jesuits in 1773, the building had various owners, until in 1874 the order regained the church. Its interior was renovated in the 1880s, and a thorough renovation was carried out in 1913.

Architecture

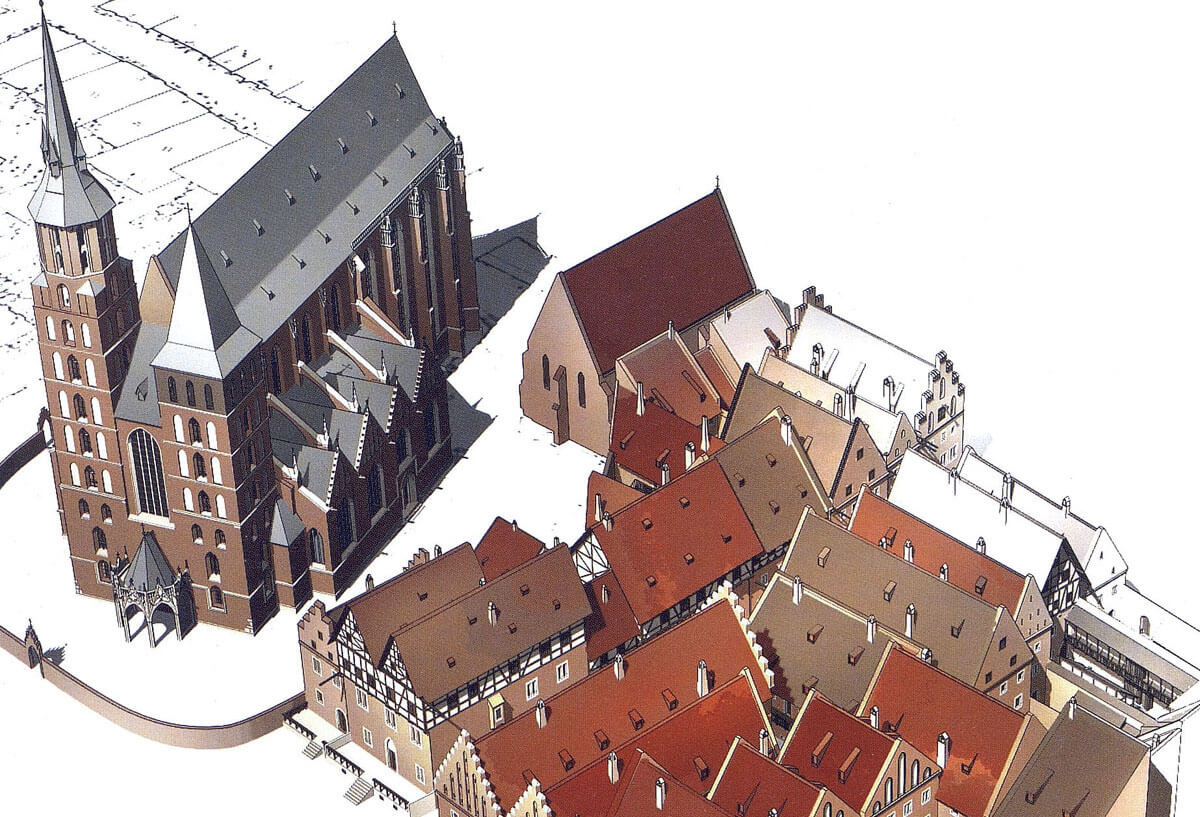

Church of St. Barbara at the beginning of the 15th century was a five-bay, orientated toward cardinal sides building, erected on a rectangular plan with dimensions of 26 x 10.7 meters, with its three-bay eastern part made up of the walls of an older chapel from the first half of the 14th century. Both the older chapel and the church from the 15th century did not have a chancel separated from the outside. Both of these buildings were also towerless, covered over the whole with gable roofs. The walls, 0.8 to 0.9 meters thick and 12.5 meters high to the cornice level, were built of bricks in a Flemish bond, while some architectural details were made of stone. At the eastern part of the northern wall there was a small, one-story sacristy, in the 15th century enlarged to the form of an annex with a residential upper floor and a gate in the ground floor.

From the outside, the walls of the church were clasped with stepped buttresses, in the corners placed at an angle. Single buttress on the axis of the west façade, between two windows, was particularly characteristic. Perhaps it was used because of the slope of the terrain, or it was related to the vault or wall faults from the inside. Interestingly, the solution with the axial buttress was repeated from the construction of the older chapel, which was basically a shorter version of the church from the beginning of the 15th century, having the same width and height. The lighting must have been different, because in the first half of the 14th century, the chapel was not yet adjacent to the buildings from the south, while the 15th-century church did not have southern windows due to the townhouses adjoined along the entire length. The eastern facade had, like the western one, two windows.

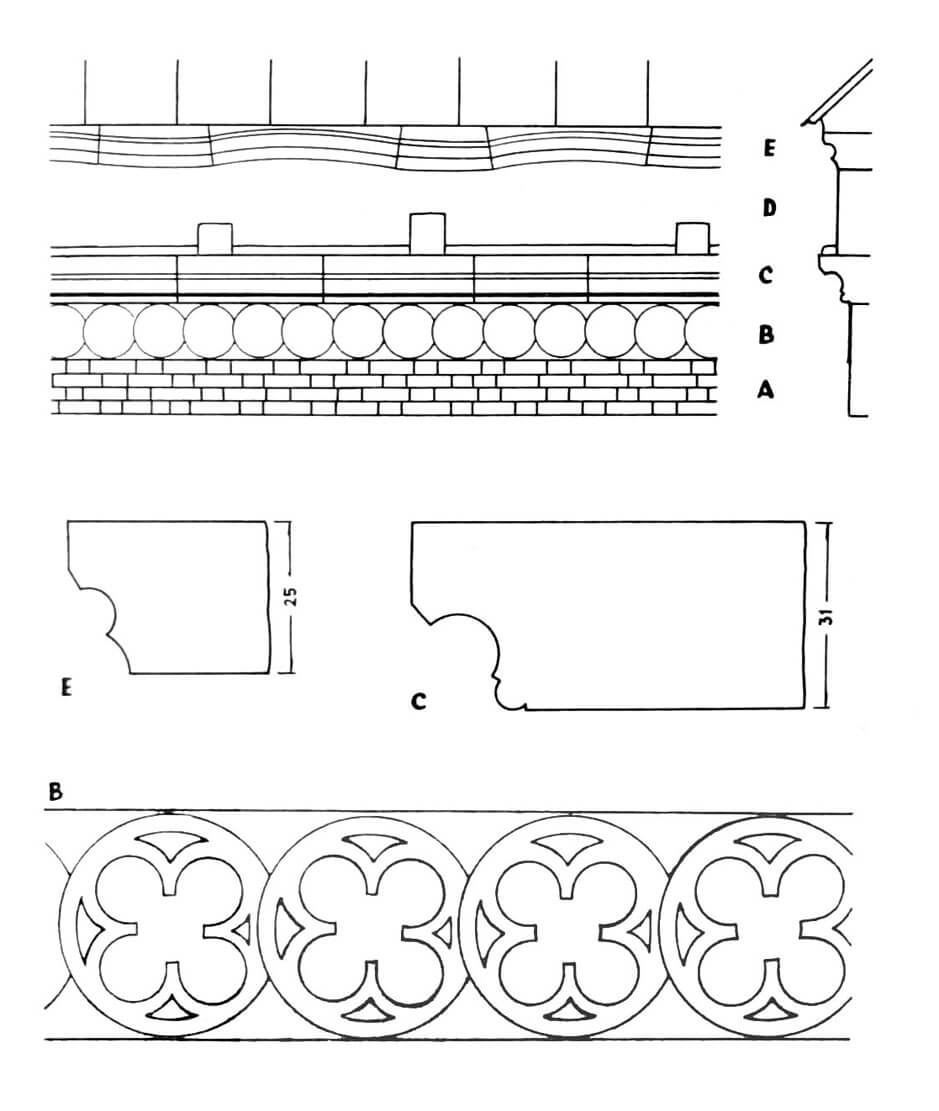

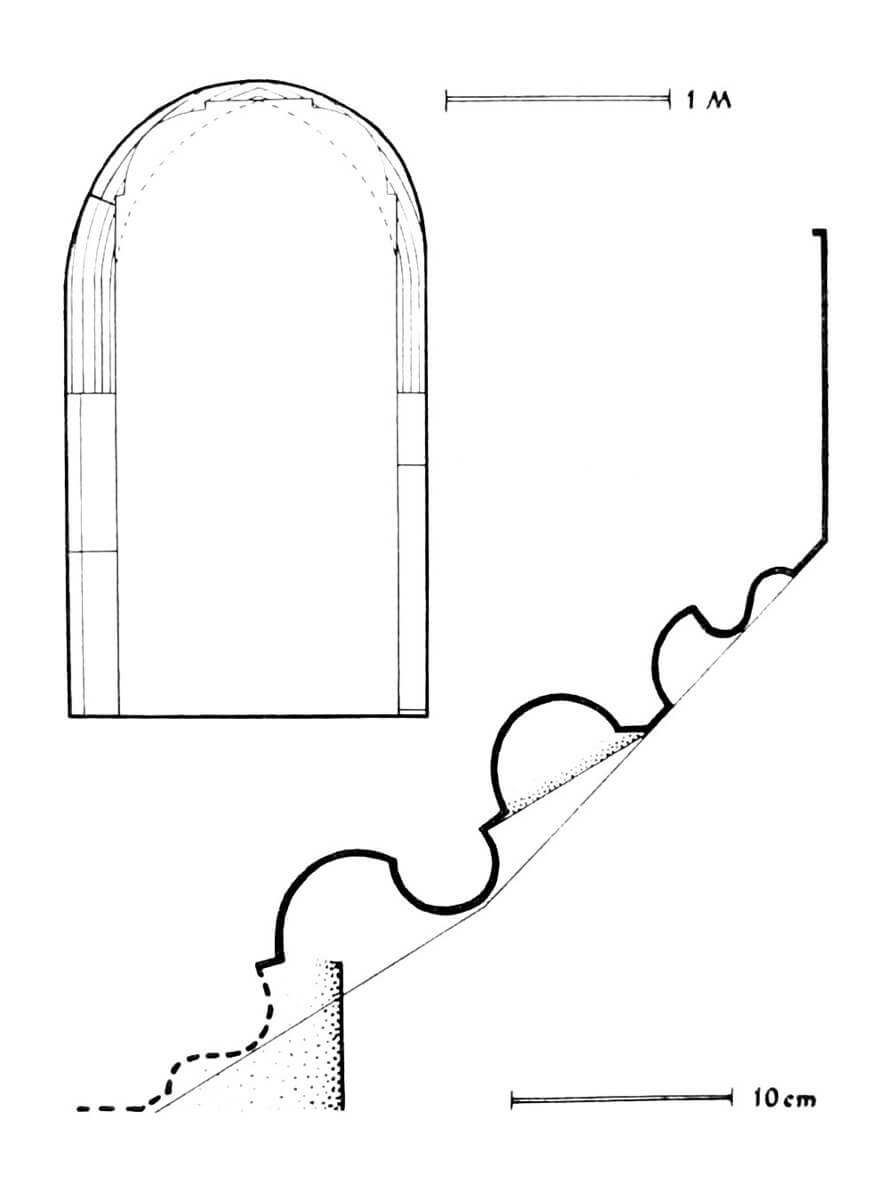

The horizontal accent of the church facades was introduced by a stone plinth and a crowning cornice, with a typical Gothic moulding with a concave and a small shaft at the bottom. In addition, just below the cornice, there was a frieze in the form of plaster covering four layers of bricks, covered with a tracery ornament with a motif of quatrefoils inscribed in circles. The cornice and the frieze were not used on the western façade, as it was decided to create one plane from the gable and the perimeter wall. At a height of about 3 meters, a stone drip cornice was led from all sides, probably bending upwards in each bay for about 30 cm.

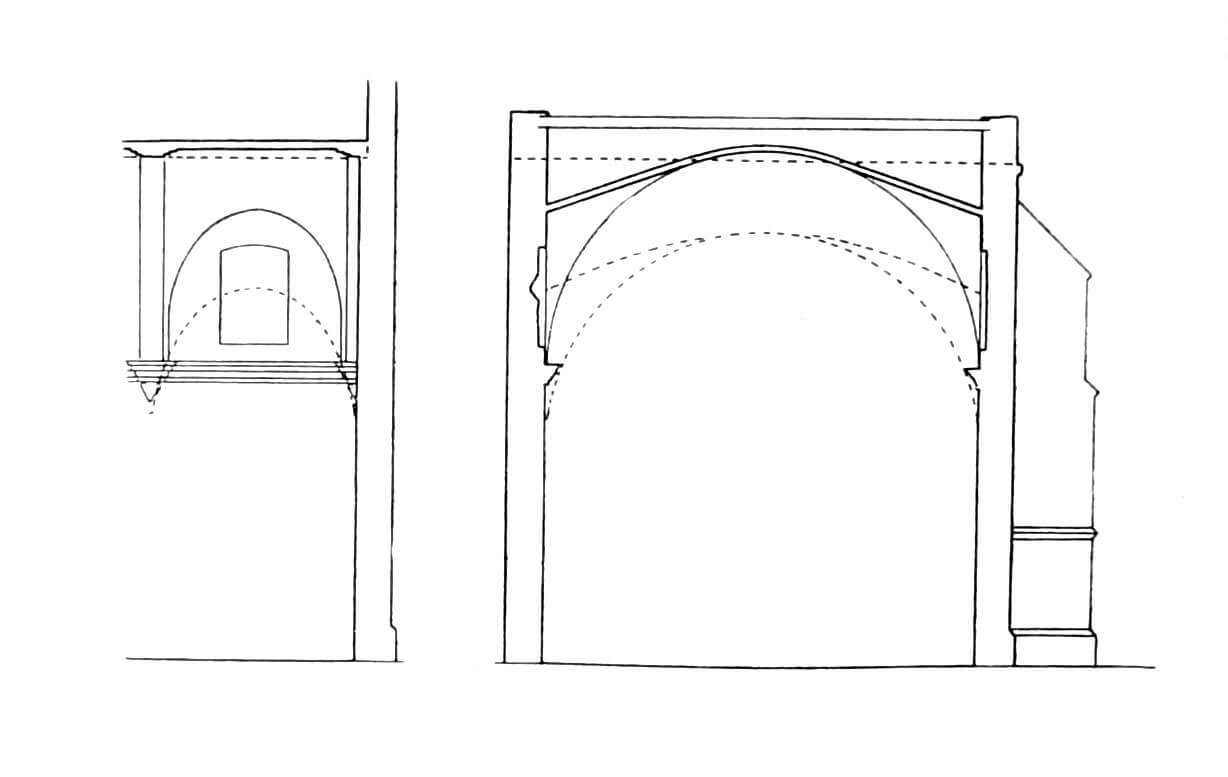

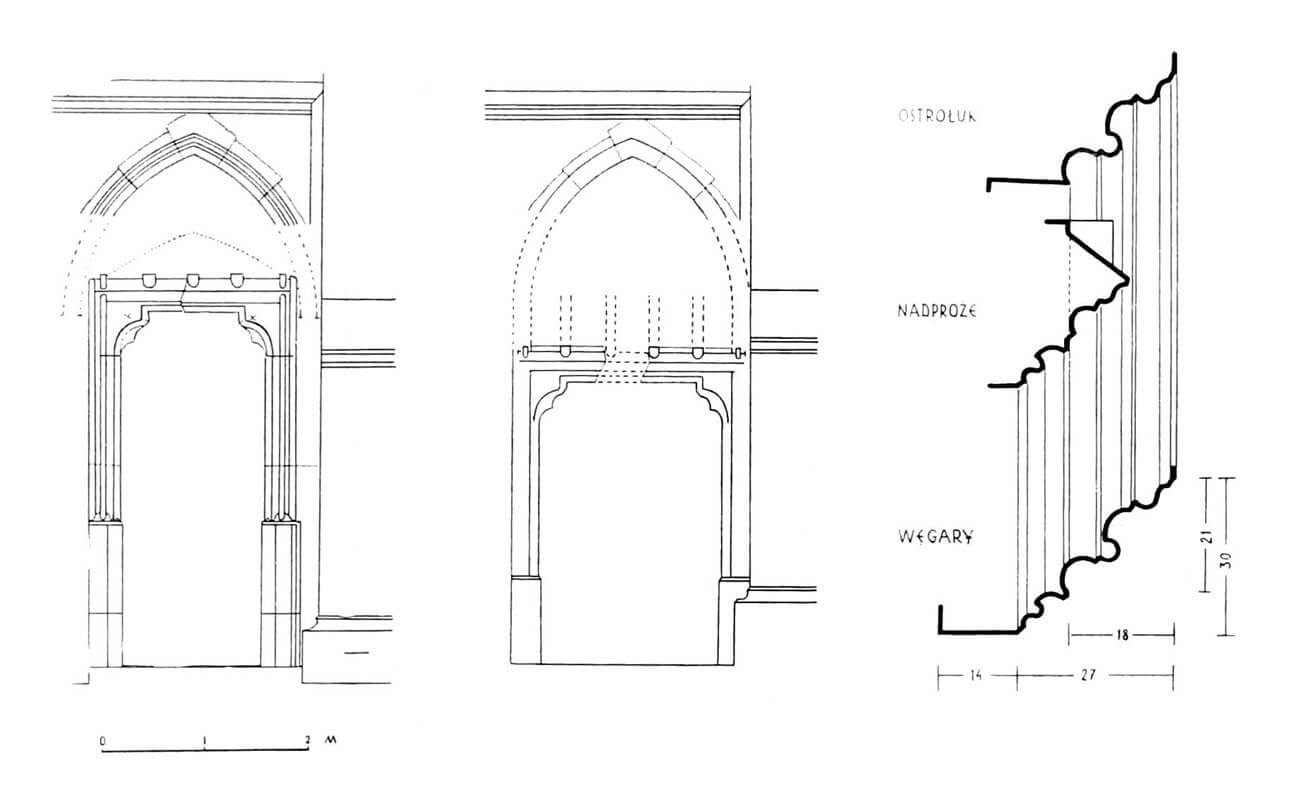

The entrance to the church led from the west, so it was facing the market square. It was not located on the axis because of the central buttress, but moved to the north. It had the form of a two-arm (saddle) portal, above which there was probably a pointed, moulded opening of the same width in the base as portal. At the end of the fifteenth century, this portal was narrowed by cutting out part of the lintel and the crowning opening was removed. The medieval church also had two northern entrances with pointed heads.

The interior of the church in the Gothic period was covered with a vault with sharp-edged, two-groove ribs, typical of Kraków buildings from the late 14th century. Ribs could form a net system over the entire nave, or a tripartite one in the extreme bays and a cross vault in the three middle bays. The second variant would be supported by a buttress in the middle of the façade. However, at no stage of the medieval functioning of the chapel and the church, the vaults together with the entire interior were not divided into two aisles.

At the end of the fifteenth century, in front of the western entrance to the church, a chapel – vestibule called Gethsemane was erected. It was formed of two bays covered with a cross-rib vault, attached to a fragment of the wall between the central buttress and the northern buttress. Outside, it was opened with three ogival arcades with exceptionally rich sculptural decorations, operating with plant and animal motifs. Each ogival arch was extended to the form of a fleuron, and between them, on the axis of polygonal pillars, pinnacles were created with canopy niches for figures. Inside, the chapel housed an altar most likely made by Veit Stoss or his workshop, consisting of a group of stone figures.

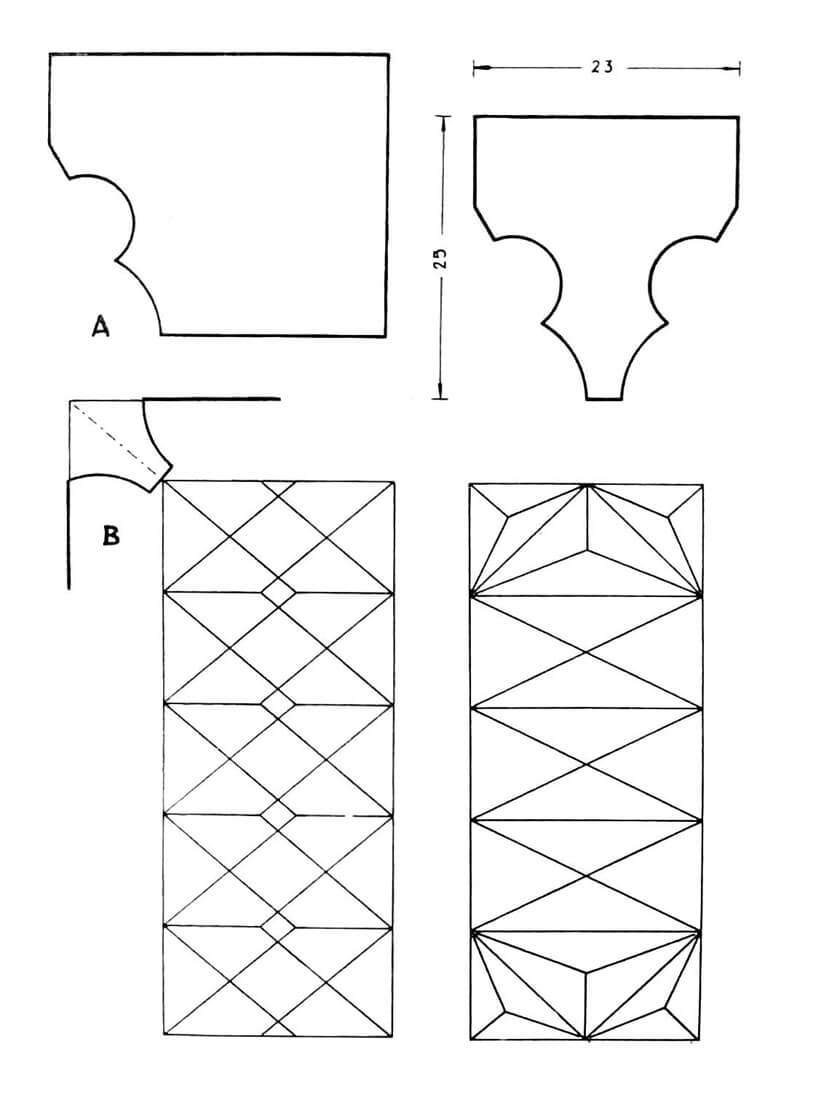

A late-Gothic annex from the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries was created at the western bay of the northern wall of the church. It had two storeys, with the first floor pierced by two four-sided, moulded windows, closed by gratings made of angular iron rods, connected by threading technique into a rhombic pattern. Below, a stone, moulded portal with a moulded ogee arch was created. The second, slightly more modest portal was placed inside the annex. Probably originally the annex was covered with a steep, shingle roof.

Current state

Church of St. Barbara is today an aisleless building, which roughly retained Gothic form, but was slightly raised, enlarged by an early modern apse on the eastern side and Renaissance or Baroque chapels on the north, over which large four-sided windows were pierced. From the south, the church is entirely covered with the buildings of the Jesuit monastery. The interior of the church has Baroque form today, but there is Gothic Pieta from the 14th century, late-Gothic paintings and modest relics of medieval ribs. The most valuable element of the church is the late-Gothic western chapel, considered a jewel of Polish Gothic architecture. It is also worth paying attention to the north-west portal of the annex from the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries and the original western portal from the beginning of the 15th century. Fragments of Gothic cornices, a frieze on the north wall and a plinth have also survived.

bibliography:

Krasnowolski B., Leksykon zabytków architektury Małopolski, Warszawa 2013.

Marek M., Cracovia 3d. Rekonstrukcje cyfrowe historycznej zabudowy Krakowa, Kraków 2013.

Paszenda J., Kościół św. Barbary w Krakowie z domem zakonnym jezuitów, Kraków-Wrocław 1985.