History

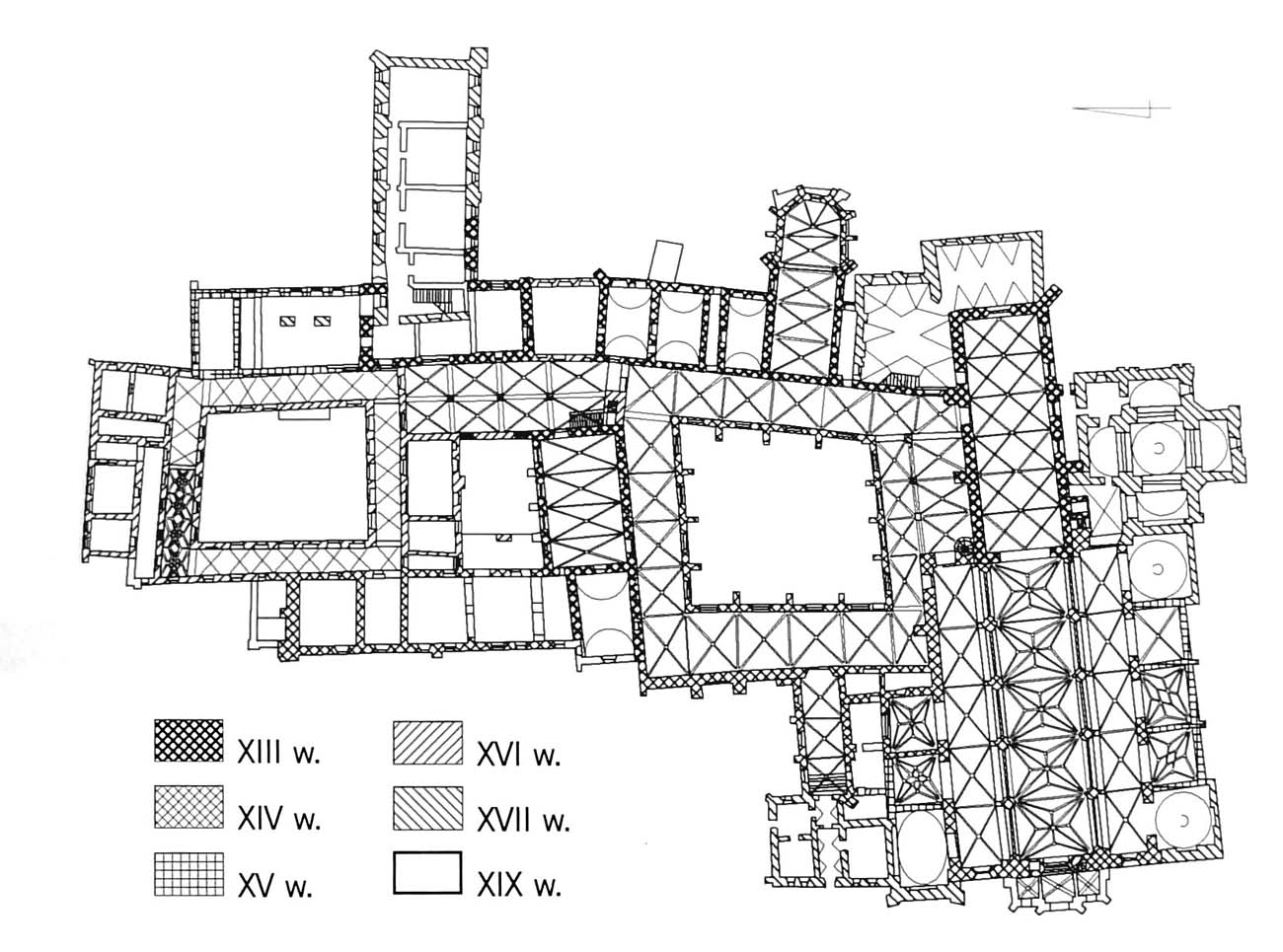

The Dominicans came to Kraków from Bologna in 1222, brought by the Bishop of Kraków, Iwo Odrowąż. They were placed at the church of Holy Trinity, which was the original parish church of Kraków, given to the monks after their arrival in the town. In 1223, the church was re-consecrated, already as a monastic one, and in 1227 bishop Iwo Odrowąż issued a privilege granting the monks the property of this building. As early as in 1225, the oldest dormitory in the friary was supposed to set fire, and in 1241, the Mongol invasion destroyed the entire friary.

In the indulgence document from 1248, Pope Innocent IV encouraged the congregation to support the reconstruction of the church and friary. In 1251, he announced another indulgence, granted to all those who would come to the monastery church on the anniversary of its consecration, although no construction works were mentioned at that time. Around 1257, brother Jacek was buried in the nave, which would indicate that the renovation and expansion of the church was completed no later than in 1258 or even a few years earlier. As a result of intensive work by the Dominicans, an early Gothic chancel was built in Kraków, one of the oldest long choirs in Europe, where Prince Leszek the Black was buried in 1289. The burial of a lay person in the choir of the Dominican church testified to his extraordinary services to the friary, which in the case of Leszek the Black could refer to financing the finishing works on the early Gothic chancel (e.g. window tracery, stained glass) or preparations for the construction of a new nave. The indulgence bull issued in 1286 by the Archbishop of Gniezno, Jakub, may also have been related to the latter. It provided income thanks to which the construction of the Gothic nave began at the end of the 13th century. Its completion took place at the beginning of the 14th century.

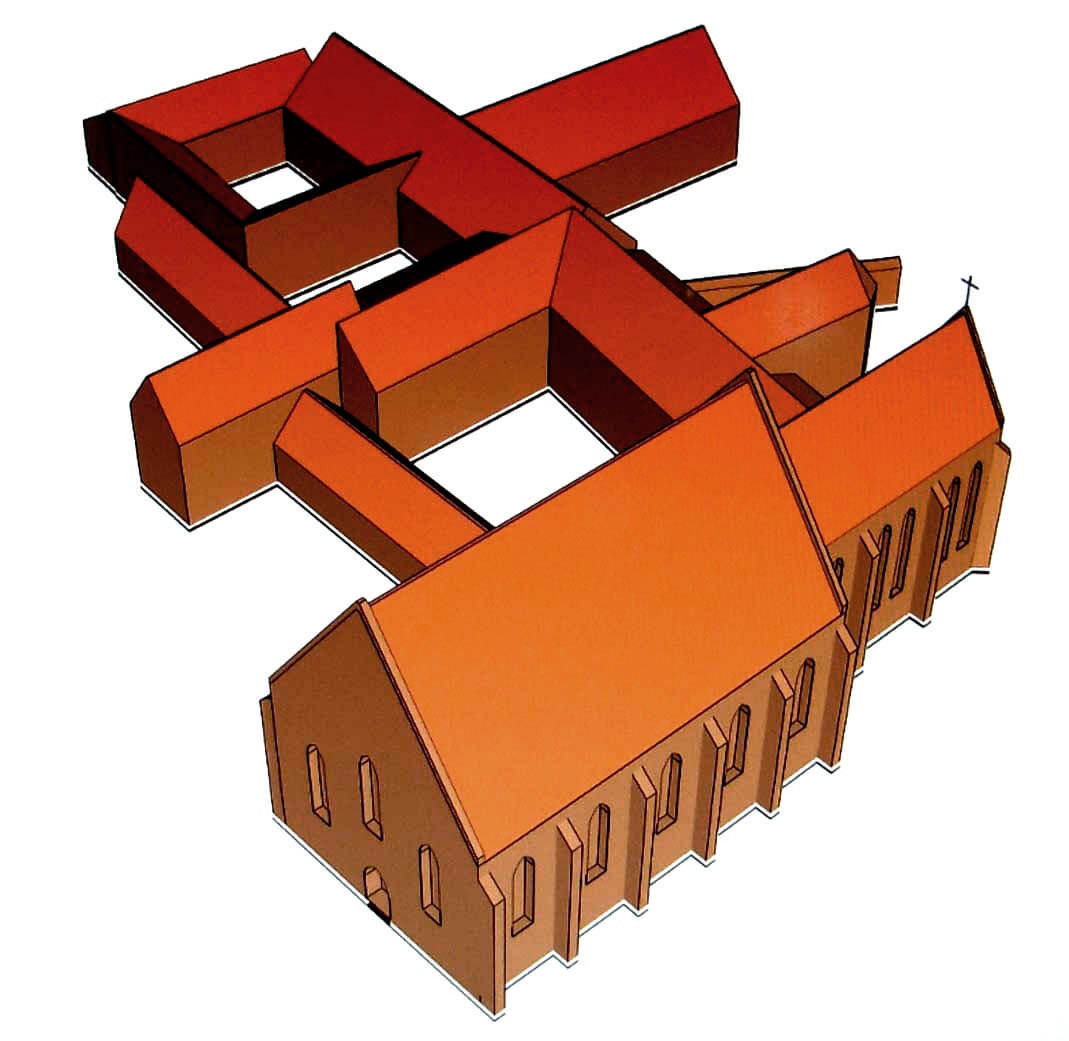

Along with the construction of the church, work on the cloister buildings were underway. The first to be built was a stone refectory, erected after the older, timber one, burnt down in 1225. At the end of the thirteenth century, the construction of the eastern wing began, which was one of the first brick buildings in Kraków and one of the oldest in Lesser Poland region. After a break caused by the Mongol invasion, work continued, thanks to which the cloisters around the courtyard formed a closed circuit in the middle of the 13th century. The next stages of the friary expansion from the second half of 13th century were carried out in the early Gothic style.

Probably in the 60s of the fourteenth century, and at the latest at the beginning of the fifteenth century, the friary church was rebuilt from a pseudobasilica to a basilica, using the pillar-buttress system previously used in the Kraków cathedral. The last stage of these works, the installation of the vault over the central nave, was financed by Piotr Szafraniec, who died in 1437. In the following years of the 15th century, the walls of the chancel were raised and vaulted again. After a fire in 1462, the chancel vault was renovated, and a new eastern gable was built, funded by a certain Katarzyna Białuszyna. Along with the reconstruction of the church in the Gothic period, the friary buildings were expanded. As early as in 1467, the indulgence “pro fabrica et structura conventus” was announced, and the Kraków murator Clemens was recorded. At the end of the 15th century, mainly repairs were carried out. In 1469, an indulgence was announced “ad reperationem ecclesiae ac domus”, in 1482 the donation was intended for “pro reperatione ecclesie”. The last medieval indulgence for church repairs took place in 1501.

The great fire of Kraków in 1850 ended of the friary splendor. The entire interior of the church burned down, except for some chapels. Despite the enormous damages, the Dominicans decided to rebuild the church. Unfortunately in 1855, as a result of defectively rebuilt two pillars between the aisles, it collapsed and caused further damages. The remaining piers, along with the walls and vaults they supported, as well as almost the entire facade, were then demolished. Then, the pillars and vaults of the nave were reconstructed almost from scratch. The work was completed in 1872, with a neo-Gothic porch added only four years later.

Architecture

Dominicans after arriving in Kraków found not very large church, built mainly of limestone, but also of sandstone. It could have had the form of a basilica with central nave and two aisles, similar in shape to the church of St. Peter in Głogów. Its inter-nave pillars were spaced every 7.5-8 meters, except for the eastern, extreme bay, where the distance was approximately 9.5-10 meters. This difference may have resulted from the desire to create a pseudotransept, preceding the chancel of an unknown, perhaps apsidal shape. The nave of the church was probably not vaulted. Presumably, on the initiative of the Dominicans, in the 1220s it was extended by about 9 meters to the west and equipped with unusual circular, corner, protruding sideways towers of an unknown height.

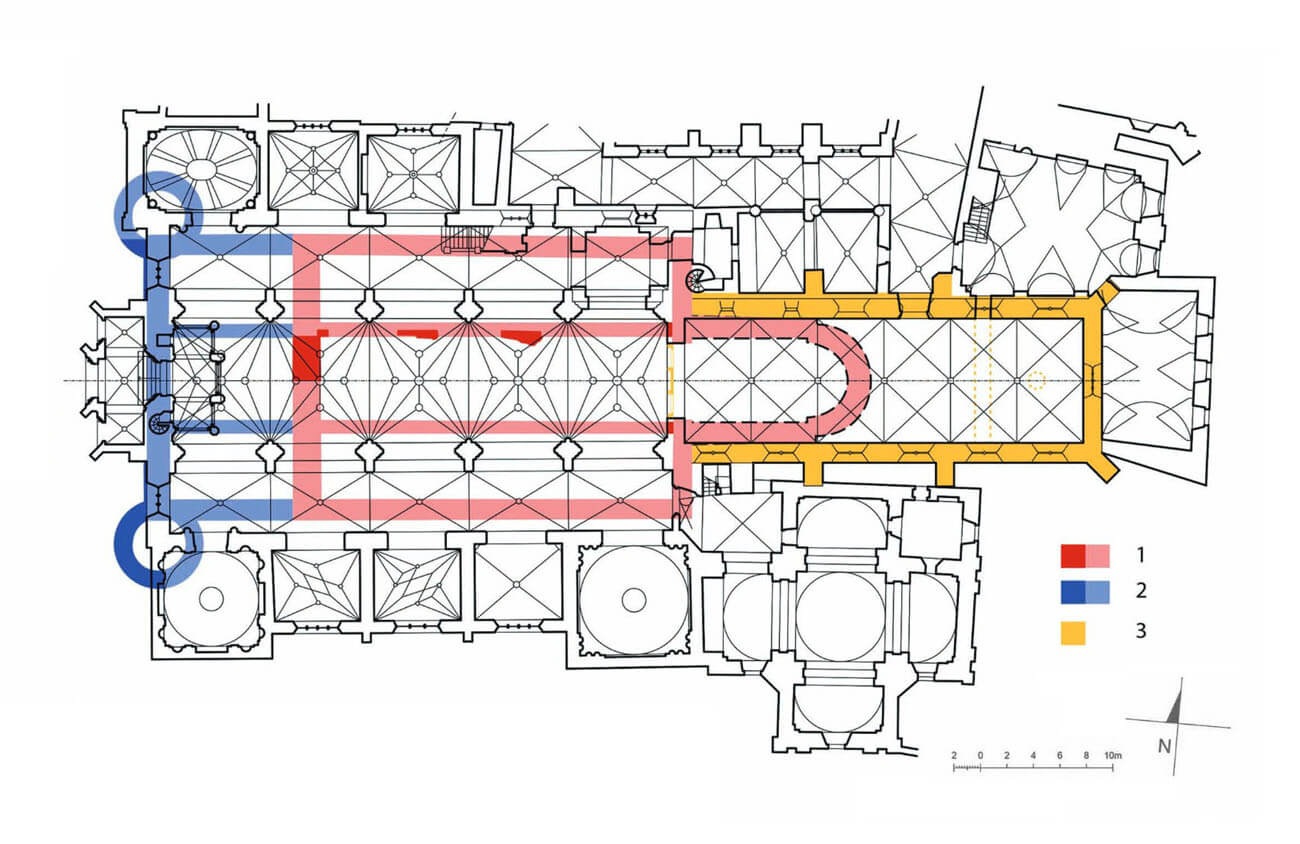

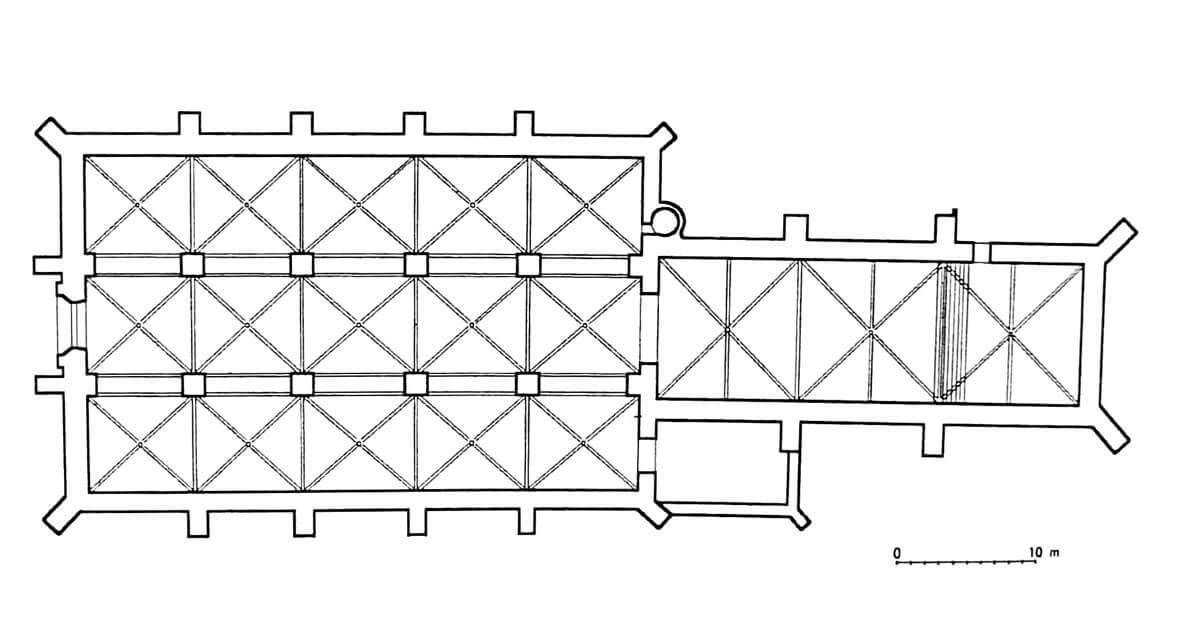

In the 1240s, an impressive chancel was added to the old nave of the church, with a strongly elongated rectangular plan measuring 30.1 x 9.4 meters. Churches of mendicant orders were opened to the whole congregation, which required dividing them into parts for monks and parts for lay people, as well as a clear architectural separation. That is why Dominicans began to build multi-bay choirs, separated from the nave of the church, with partitions – rood screens inside, just like in the case of the Dominicans in Kraków. Long choirs were also necessary due to the addition of stalls, i.e. wooden benches for the monks, situated along the walls.

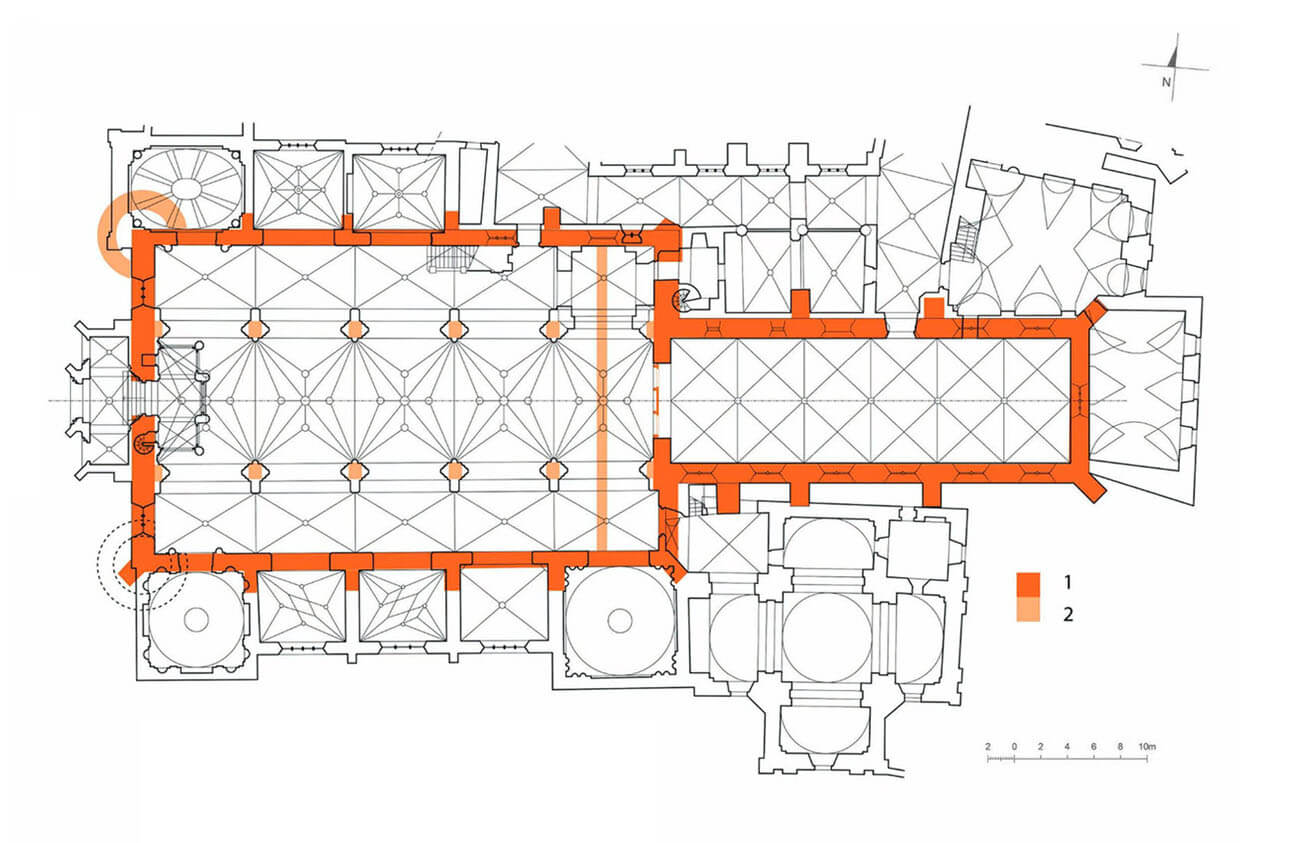

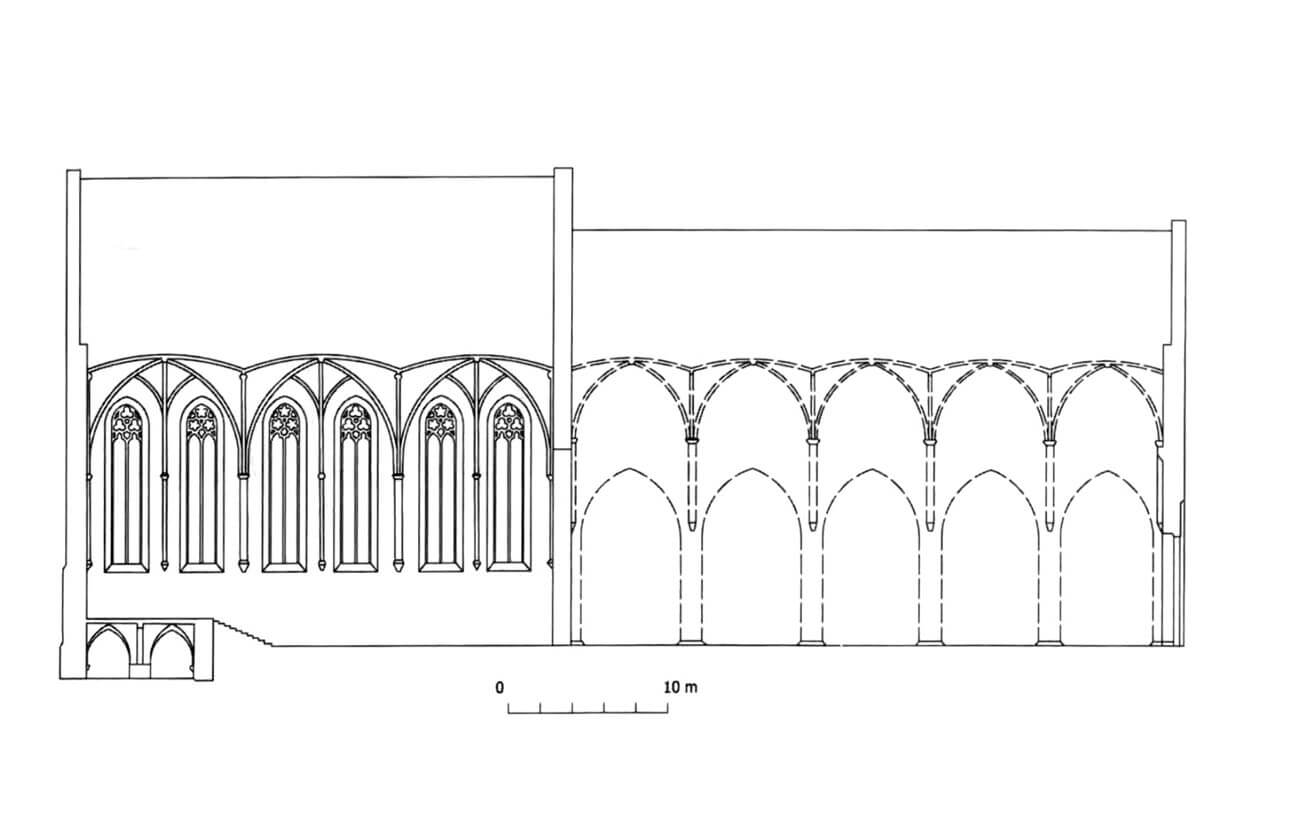

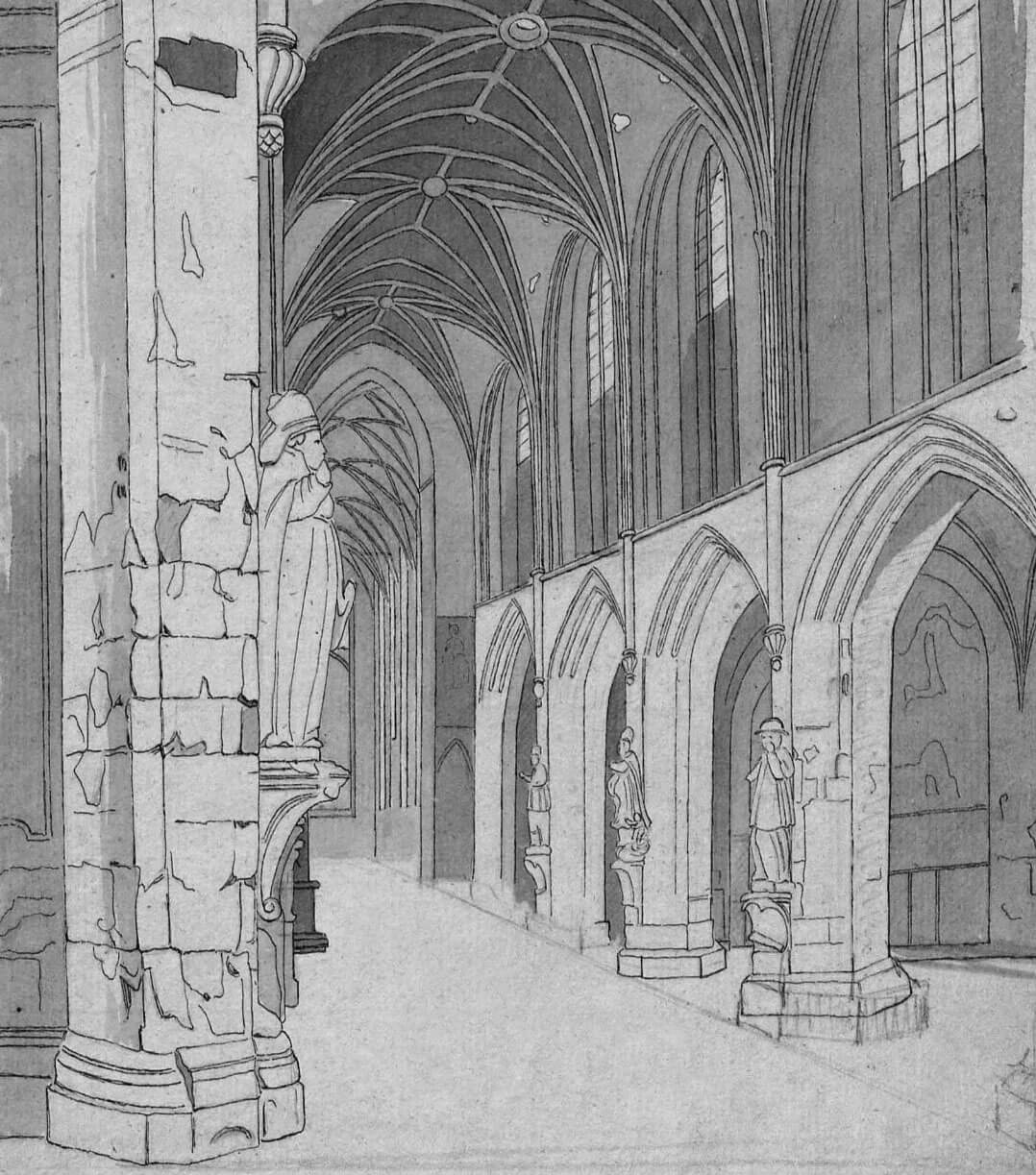

Originally the chancel of the Holy Trinity church was covered with a six-part vault over three square bays, springin from suspended shafts, alternately semi-octagonal and semi-circular. The floor was made of ceramic tiles. They were multi-colored (tin-brown, yellow and green), had embossed geometric (plaitwork), plant (palmette) and figural (griffin, deer hunting) ornaments. Under the eastern part of the chancel there was a crypt partially sunk into the ground. The rood screen separating the choir from the central nave had two passages flanked by columns on the sides, quite archaic in relation to the advanced articulation of the walls. The columns were equipped with classic Attic bases with two thick, solid rings, separated by a wide concave. The lower torus, equipped with leaves, although extended in front of the outline of the plinth, did not yet show the flattening characteristic of the early Gothic style. The interior of the nave from the end of the 13th century was also covered with rib vaults, supported by stone wall-shafts that were circular in cross-section. In the central nave, they were suspended between pointed arcades, above four-sided pillars dividing the space of the entire nave into square bays.

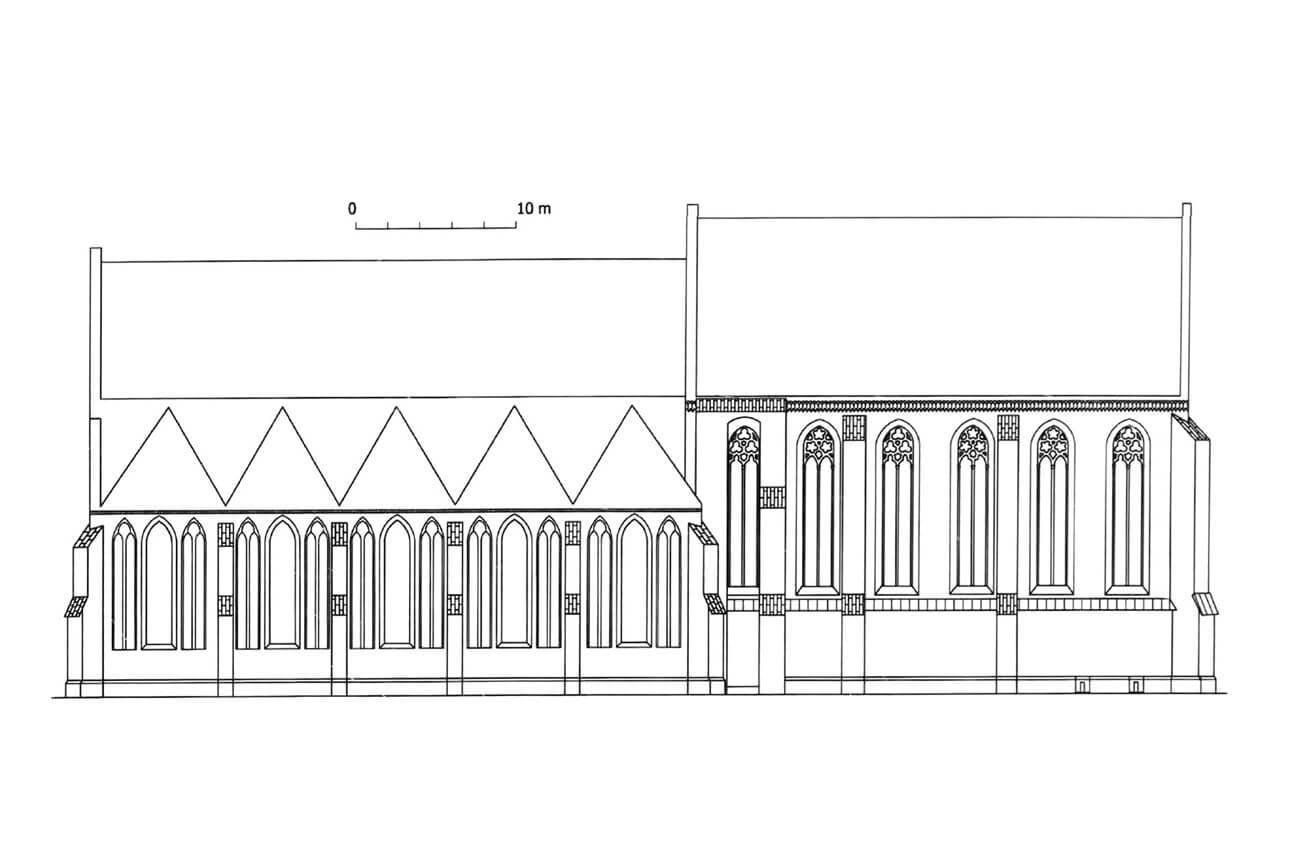

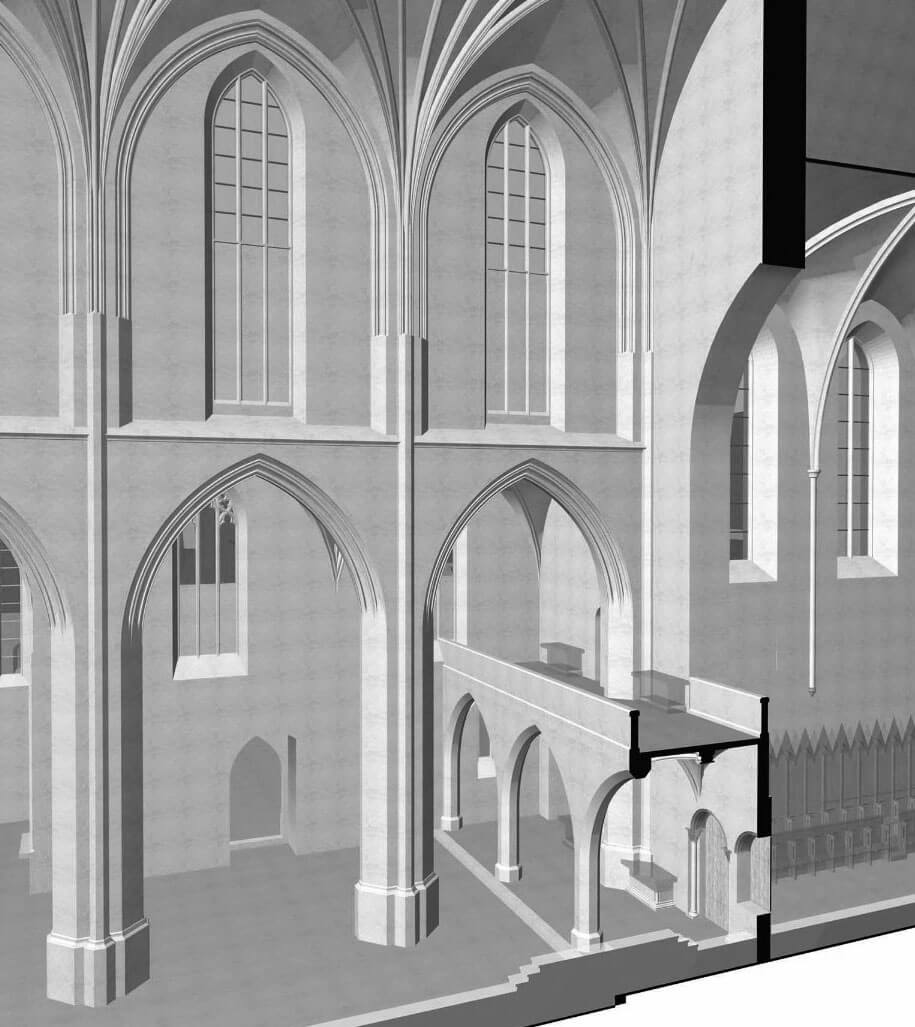

As a result of reconstruction from the second half of the 14th century and the first quarter of the 15th century, the church of Holy Trinity became a slender five-bay basilica with the internal length of the nave 37.1 meters and 23 meters wide. It was decided to keep the older perimeter walls, but to replace the intermediate piers, which had to support the new, very high walls of the clerestory and vault. The nave was built in the pillar-buttress system typical of Kraków and connected to the old, elongated chancel, ended with a straight wall in the east. Around the mid-15th century, the chancel walls were raised to make them equal to the high of central nave.

After the expansion in the second half of the 14th century, the church was still surrounded by stepped buttresses, because they also supported the chapels. The western facade of the central nave was topped with a stepped gable with pinnacles, and below there was a large ogival window, flanked by slightly smaller windows of the aisles. The eastern wall of the chancel after the walls were raised was also topped with a high stepped gable, separated by pyramidally arranged blendes with stepped frames and topped with pinnacles. Below, the wall was pierced with a large, pointed window. Additional two-light windows, splayed on both sides, illuminated the chancel from the south, two per bay (older tracery from the 13th century was used in them). The central nave and side aisles were illuminated by single three-light windows, and over time, the role of illuminating the aisles was taken over by wide, pointed, three-light and four-light windows of the chapels. The main entrance to the church led through a western, pointed-arch, stepped portal with rich sculptural decorations, with plant and zoomorphic motifs in three orders. The portal was also decorated with a carved impost frieze, bas-relief representations on the capitals, and openwork tracery in the tympanum.

Inside, the central nave was separated from the chancel by a pointed rood arcade with impost cornices on two levels. The division into aisles was provided by pillars in the shape of elongated octagons, set on plinths, with buttresses on the side of the side aisles and wall shafts reaching down to the floor on the side of the central nave. The central nave was opened to the aisles with pointed arcades with moulded archivolts, above which there was a moulded cornice separating the slightly recessed window zone of clerestory, placed in moulded, pointed recesses. The moulding of the arcades’ archivolts was originally embedded in the internave pillars, which were smooth to the plinths. The central nave was covered with a stellar vault, the aisles with cross-rib vaults, and the chancel with a vault with a uniform network of ribs. The latter was lowered onto the wall shafts and fastened with bosses in the form of coats of arms. There were also wall shafts in the central nave, and in the aisles there were corbels in the form of half an inverted pyramid.

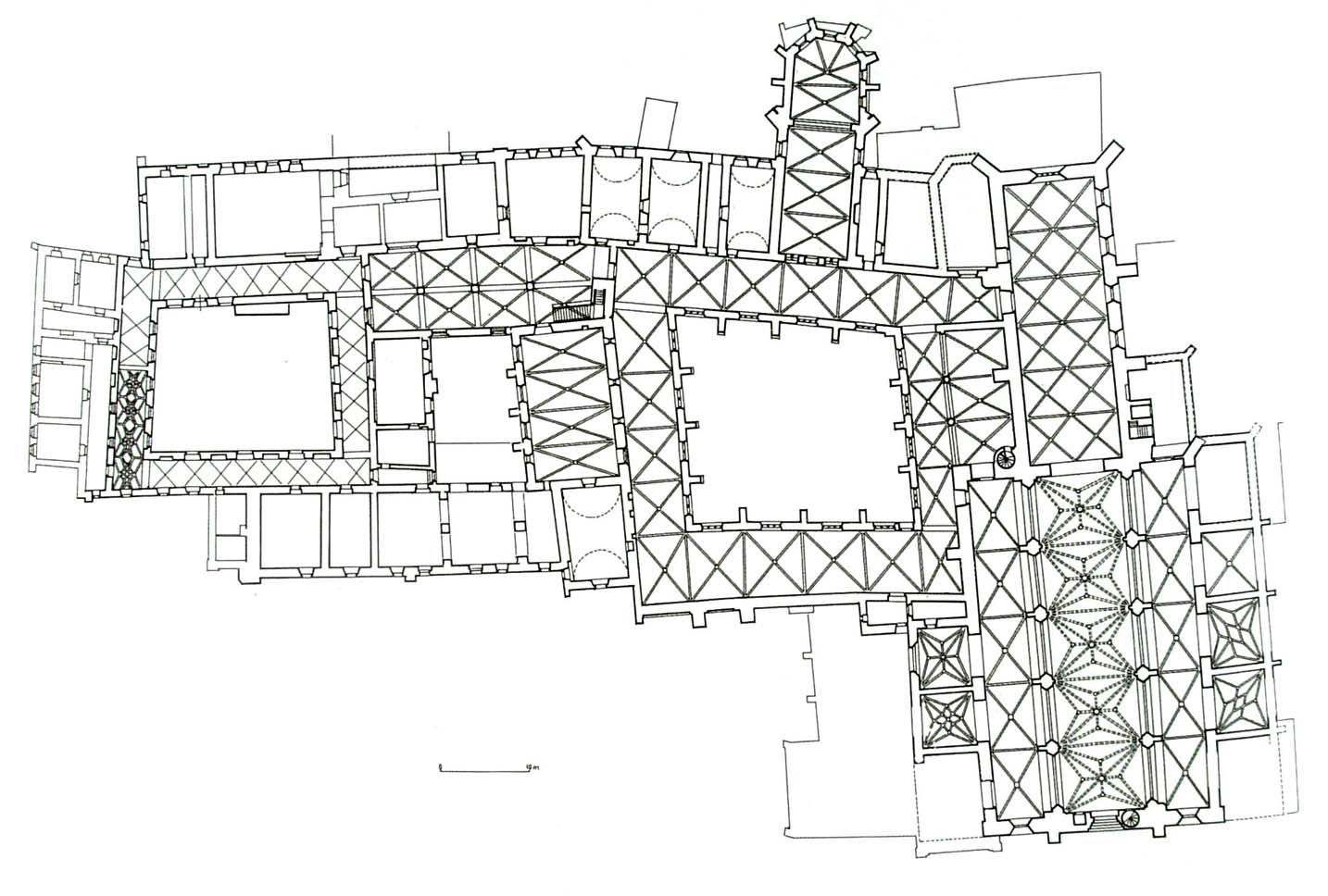

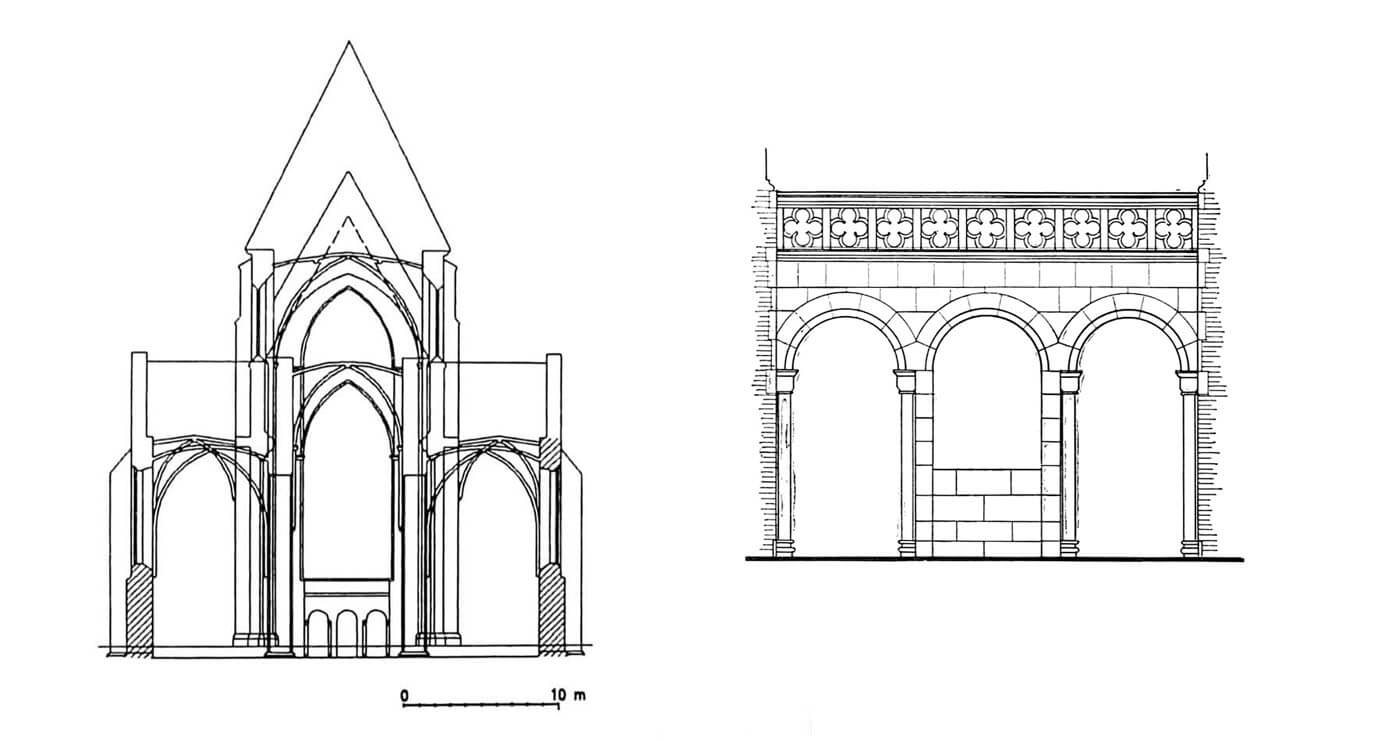

The friary buildings were situated on the northern side of the church. Their oldest, Romanesque building was the refectory, a room measuring 15.9 x 9 meters, built of irregular limestone (the so-called wild stone) and sandstone ashlar in the corners. It had two storeys: a two-aisle rectangular basement room that served as a cellarium and the upper storey where monks eat. Cellarium was divided into two parts by three massive, four-sided pillars, supporting cross vaults with the arch bands. The original height of the lower room did not exceed 2.3 meters, the plan was 5 x 15 meters, and the walls were about 1.4 meters thick. It was illuminated by small semicircular and rectangular windows in the northern, southern and eastern walls. Initially, it was accessible only through a barrel-vaulted passage with stairs on the west side. The room on the first floor, originally 4 meters high, with walls about 1 meter thick and covered with a wooden ceiling, was in the 15th century crowned with a cross-rib vault and covered with wall polychromes. From the eastern side, the access of light was originally provided by a triad of semicircular windows with an oculus in the middle, and an additional three Romanesque windows were pierced in the southern wall. There, near the western corner, there was an entrance portal: a three-step, closed semicircular, with a carved motif of a plant braid in the central part of the archivolt. The longer wall of the refectory was attached to the garth in the south. The cross-ribbed vaults of the cloisters were built in the 14th century.

The eastern range in the second half of the 13th century was a building measuring 11 x 44 meters with corners reinforced with buttresses and a chapter house protruding to the east. The range was situated at an unusual angle in relation to the church, which would indicate its earlier date of erection. It had two floors. In the ground floor there was a sacristy from the south, a 6-meter wide room, the aforementioned chapter house, a room 4.5 meters wide, a passage leading from the cloister to the friary gardens, and two similar rooms 5 meters wide.

The chapter house, strongly protruding in front of the friary’s facade, was originally short, three-bay (7.5 x 4.5 meters) and closed with a straight wall at the height of diagonal buttresses. It faced the cloister with the facade, in which the entrance portal was placed, flanked by two pairs of twin, lancet windows. The architectural composition of the front wall of the early Gothic chapter house was probably inspired by the form of the older late-Romanesque chapter hall with a semicircular portal and two tow-light openings on its sides. The eastern part of the chapter house, after being extended in the fourteenth century, was closed with three sides, and the whole was covered with a cross-rib vault.

The early Gothic period is related with a building with a plan similar to a square with a side of 10.5 meters, located north of the eastern wing. It had two floors, the lower one being a cellar partially recessed into the ground, with cross vault on the central pillar. The ground floor was 7 meters high, illuminated with ogival windows and probably also vaulted on a single pillar. This building may have housed the oldest libraria, connected with the theological study located next to it, or the winter refectory (relicts of the fireplace were here discovered).

At the end of the Middle Ages, the monastery buildings were concentrated around three garths: the largest southern one, the smallest centrally located, and the third, the youngest, located in the northern part. All three cloisters were connected by the 90-meter long east wing, running diagonally from the north-east to the south-west. However, the friary did not have a west wing at the main courtyard, only the entrance to the claustrum led there.

The cloister around the first, trapezoidal garth was characterized by arms of various widths. It was cross-vaulted with ribs fastened with circular bosses and lowered onto pyramidal, moulded or tracery corbels, as well as exceptionally two consoles carved in the shape of a bird with a human head and with floral decorations. The large, pointed windows of the cloister were splayed on both sides. At the northern part of the east wing, on the extension of the eastern arm of the cloister of the first garth, a late-Gothic, strongly elongated, two-aisle, four-bay vestibule was placed. It was topped with cross-rib vaults based on arch bands and three octagonal pillars. In its south-west corner there were two-flight stairs built leading to the upper large passage, a descent to the basement under the refectory and a portal leading to the refectory.

From the east, three rooms dating back to the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries were attached to the Gothic vestibule. Originally there was a two-story brick building without a basement, covered with pilaster strips, erected on a rectangular plan with external dimensions of 21 x 10.8 meters. Its ground floor was divided into two rooms: the larger northern one and the smaller southern one (existing until today and called the Treasury). Soon the larger room was divided into two more rooms. All of them were vaulted from the beginning, and the main entrance was located in the central part of the west facade. The building was illuminated by Romanesque two-light windows with rectangular jambs and a semicircular heads. The first floor was accessible by stairs hidden in the thickness of the western wall. It is uncertain what function the building played, perhaps it housed a provincial theological study.

The cloister of the third garth in the western part of the northern arm was topped with a net vault, and the rest had a cross-rib vault. At the eastern and northern arms of the cloister, buildings with many rooms were erected in the 15th century. The elongated, rectangular building also reached the middle of the western arm of the third garth, connecting in the south with the corner of the refectory and a 13th-century room rebuilt in the 15th century.

Current state

The peripheral walls of the 13th-century church, expanded in the 14th and 15th centuries, have been partially preserved to this day. The walls and vault of the chancel, some of the chapels, as well as the perimeter walls of the nave from the north, south and east have survived. However, today the nave is largely a neo-Gothic work. It repeats the dimensions and bay divisions of the original church, but differs in details. Unfortunately, the vault of the 13th-century crypt under the chancel destroyed in the 19th century, along with the entrance to it modified in 1938. During the reconstruction, the church facade was covered with a neo-Gothic porch. Some of the side chapels were rebuilt in the 17th century in the Baroque style and then in the 19th century in neo-Gothic forms.

Currently, in the two southern windows of the chancel of the monastery church, the original tracery is visible, re-inserted after the walls were raised in the 15th century, and in the western porch there is a portal from the second half of the 14th century, but a large part of the architectural detail of the church was destroyed during the fire of 1850. The result of the reconstruction is the western gable and vaults in the nave, mounted on completely new pillars, moulded unlike the original straight ones. The vaults of the aisles are among the best rebuilt fragments of the nave, and the two-story arrangement of the wall of the central nave was repeated without any major deviations. Only the prominent rings covered with plant decorations, separating the polygonal and moulded sections of the pillars, are entirely a 19th-century creation. The vault of the central nave with the sequence of four-pointed stars was renewed without changes, except for the coats of arms and initials placed on the bosses. The motifs of the window tracery in the nave are entirely modern.

During the long history of the friary, the cloister buildings were more fortunate than the church, with numerous Romanesque and Gothic elements you can admire today. The oldest preserved part of the claustrum is the Romanesque refectory, and the Gothic chapter house or the late Gothic vestibule are also valuable rooms. In the cloister there are several Gothic and Romanesque portals, as well as a 13th-century window with tracery, which once illuminated the rood screen of the early Gothic pseudo-basilica from the north.

bibliography:

Architektura gotycka w Polsce, red. M.Arszyński, T.Mroczko, Warszawa 1995.

Bober M., Architektura przedromańska i romańska w Krakowie. Badania i interpretacje, Rzeszów 2008.

Bojęś-Białasik A., Czechowicz J., Czyżewski K., Szyma M., Walczak M., Przegroda chórowa i lektorium w kościele Trójcy Świętej w Krakowie. Rekonstrukcja-datowanie-użytkowanie, “Biuletyn Historii Sztuki”, 83/2021.

Bojęś-Białasik A., Czechowicz J., Łyczak M., Szyma M., Krakowski kościół Świętej Trójcy w średniowieczu. Fazy budowy w świetle najnowszych badań, “Rocznik Krakowski”, 88/2022.

Bojęś-Białasik A., Niemiec D., Klasztorne fundacje biskupa Iwona Odrowąża w świetle wyników badań archeologiczno-architektonicznych klasztoru Dominikanów w Krakowie i opactwa Cystersów w Mogile [w:] Działalność fundacyjna biskupów krakowskich, t. 1, red. M. Walczak, Kraków 2016.

Goras M., Zaginione gotyckie kościoły Krakowa, Kraków 2003.

Krasnowolski B., Leksykon zabytków architektury Małopolski, Warszawa 2013.

Szyma M., Kościół i klasztor Dominikanów w Krakowie. Architektura zespołu klasztornego do lat dwudziestych XIV wieku, Kraków 2004.

Świechowski Z., Architektura romańska w Polsce, Warszawa 2000.

Walczak M., Kościoły gotyckie w Polsce, Kraków 2015.