History

Since the 10th century Kraków played a role in far-reaching trade, and in the 12th century, when it became the seat of the ruler residing in Wawel, it was already an important trade center. In the thirteenth century, the city entered into trade for the so-called The Royal Route (Via Regia), one of the most important transport links in Central Europe on the east-west line, created from many older and younger roads, routes and medieval connections. Large transit routes connecting Gdańsk and Toruń with the Hungary, as well as German countries and Bohemia with Ruthenia and the Black Sea zone intersected in Kraków. Such a favorable location resulted in the need to erect commercial infrastructure, especially after the shape of the city was regulated in the foundation privilege of Bolesław the Chaste from 1257.

The first commercial buildings in the form of cloth halls and stalls were built in Kraków shortly after the issuance of the charter document, in which Bolesław the Chaste included a clause with the obligation to build at his own expense a chambers for selling cloth (“camerae, ubi panni venduntur”) and a chamber commonly known as “cram”. The majority of the income it provided was to go to the ruler, and a sixth to the mayor. Cloth halls were so valuable that from the beginning of the 14th century they were recorded in numerous commercial transactions concerning changes in ownership and size, including stalls and bread benches (“bancos pannum”, “banca pannis”). Trading posts were often identified by the names of former or current users, because their ownership did not undergo massive, rapid changes.

In the 14th century, Kraków was already one of the most important commercial transit centres. From 1306, it had the right to store copper, and from 1342 to store cloth, which is why around 1358 King Kazimierz the Great funded a new, brick building of the Cloth Hall. In addition, he organised and extended the previous privileges of the townspeople, and also transferred real estates and rents from the commercial facilities belonging to the ruler. The king also gave the city the right to own weigh, a silver melting plant, a gold purification plant and a cloth shearing place, along with the income generated by them. The ruler’s only condition was that the city should not be disfigured by haphazardly placed new buildings. From then on, people could sell cloth only in the appropriate chambers, and divide and cut only with the help of local merchants, in designated places (the shearing room was first recorded in 1358 – “casae in quibus panni tondentur”).

Gothic cloth hall building was enlarged and rebuilt significantly at the turn of the 14th and 15th centuries, together with Wealthy Stalls that replaced earlier Bolesław’s Stalls. In 1390, the roof over the cloth hall was repaired and paving was laid inside the building. Further work on the shearing room and cloth hall two years later was supervised by a certain Martin Lindintolde. Moreover, in the second half of the 14th century, brick buildings of the Great and Small Weigh were erected, intended for offices which were associated with privileges guaranteeing a monopoly on the collection of fees, like the institutions of customs, taxes called “szrot” or cloth cutting places. The first record of the Kraków weighbridge was recorded in 1302, but the great privilege of Kazimierz the Great from 1358 mentioned two scales (“duas pensas”). From that time on, the old Lead Weigh was called the Great Weigh, because it was used to weigh heavy goods (lead, copper, iron). In contrast, the Small Weigh was used to weigh lighter wax, pepper, and other products weighing less than one hundredweight.

The Gothic commercial buildings were destroyed in a fire in 1555, when the shoemakers’ stalls caught fire and from there it spread to the town hall and the cloth hall. In the years 1556-1559, the cloth hall was renovated in accordance with the Renaissance style reigning in the architecture at that time. The work was led by master Pankracy, who closed the great hall of the cloth hall with barrel vault. The building was topped with an attic with arcaded divisions and a ridge with gargoyles designed by king’s sculptor Santi Gucci. The column loggias designed by Jan Maria Padovano were also added. In the years 1599 – 1602, the transverse passages of the cloth hall were rebuilt and floors were added to them. At the end of the 16th century, the Great and Small Weighbridge buildings were also rebuilt in a late Renaissance style and throughout the century, modernization works were carried out on small commercial buildings, as they were most often subject to fires and normal wear and tear. This was also related to the relaxation of medieval regulations requiring trade to be conducted in the central market square buildings.

The city’s heyday, and consequently trade and commercial development, ended with the transfer of the capital to Warsaw at the beginning of the 17th century and the occupation of Kraków by the Swedes in 1655. New investments in commercial development were few and carried out on a small scale, with the focus primarily on renovation works. Thanks to this, commercial buildings survived in their early modern form until the 19th century. First, in 1801, the Small Weigh was demolished, then, as part of the cleaning of the market square, in 1868 the already ruined Wealthy Stalls were removed, around 1879 the Great Weighbridge building was slightened, and in the years 1875-1879, the Cloth Hall was rebuilt. At that time, projections were added on the east-west axis, as well as ground-floor arcades. Further renovations of the Cloth Hall, involving the removal of 19th-century details, took place between 1955 and 1959. The interiors were renovated between 1977 and 1979.

Architecture

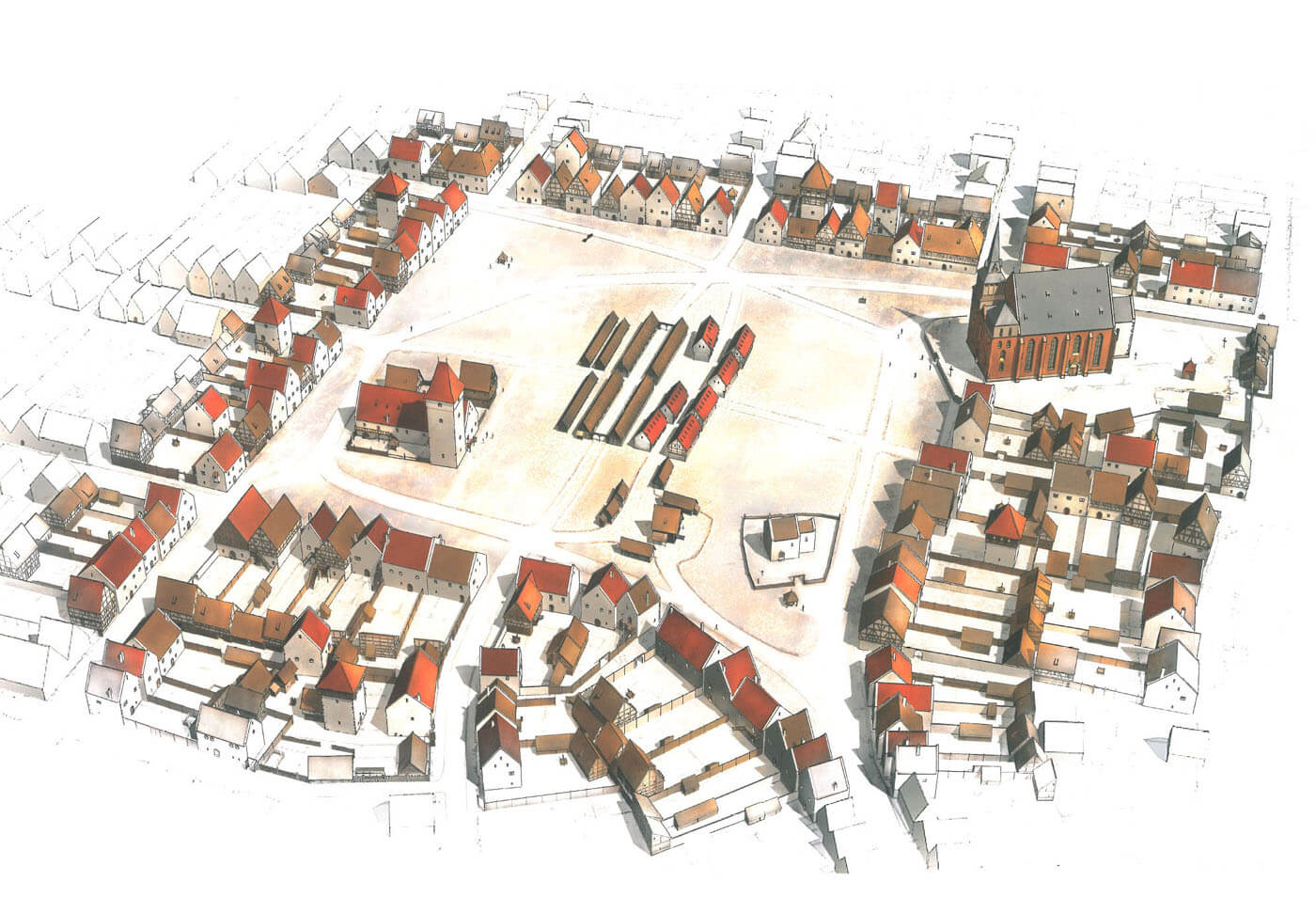

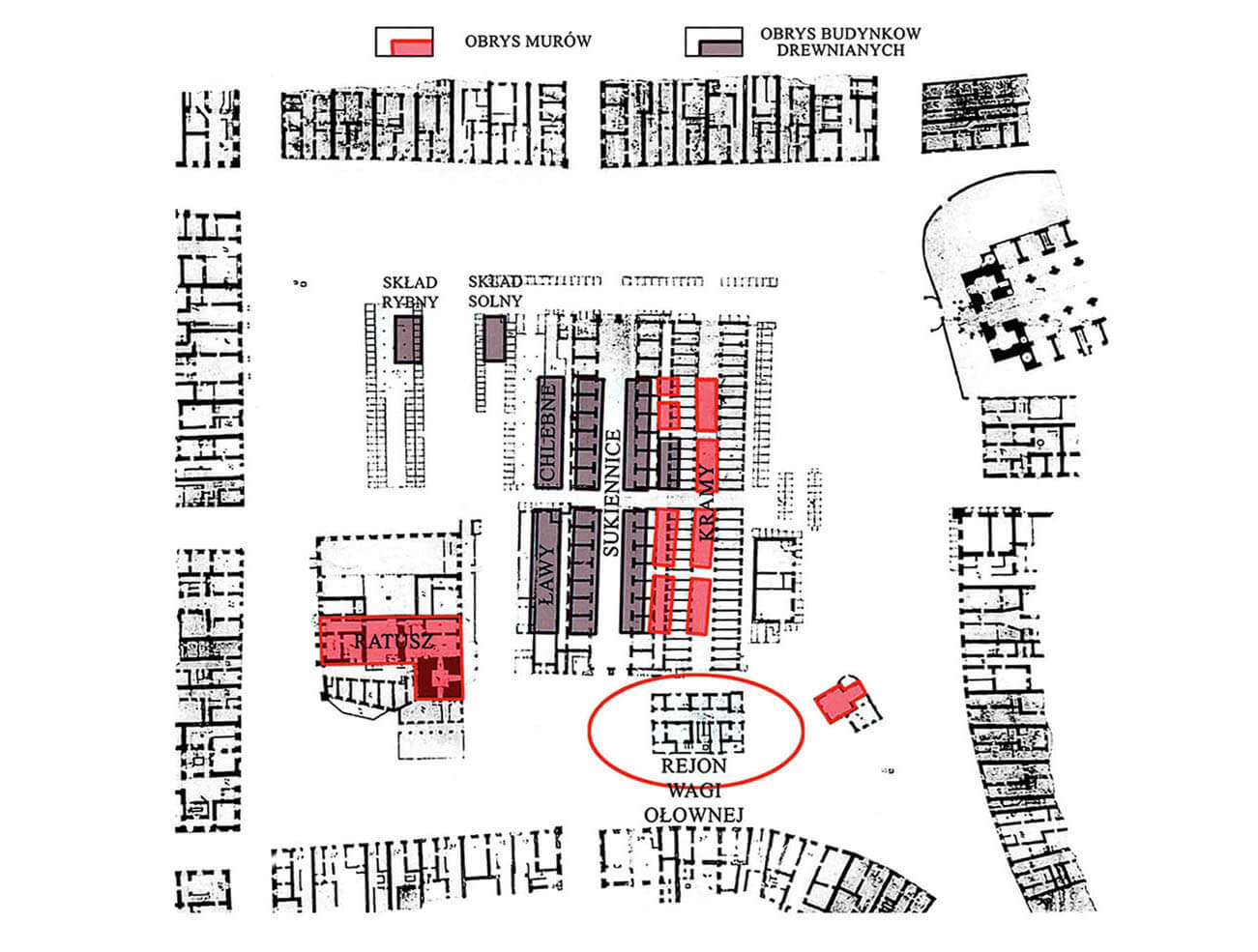

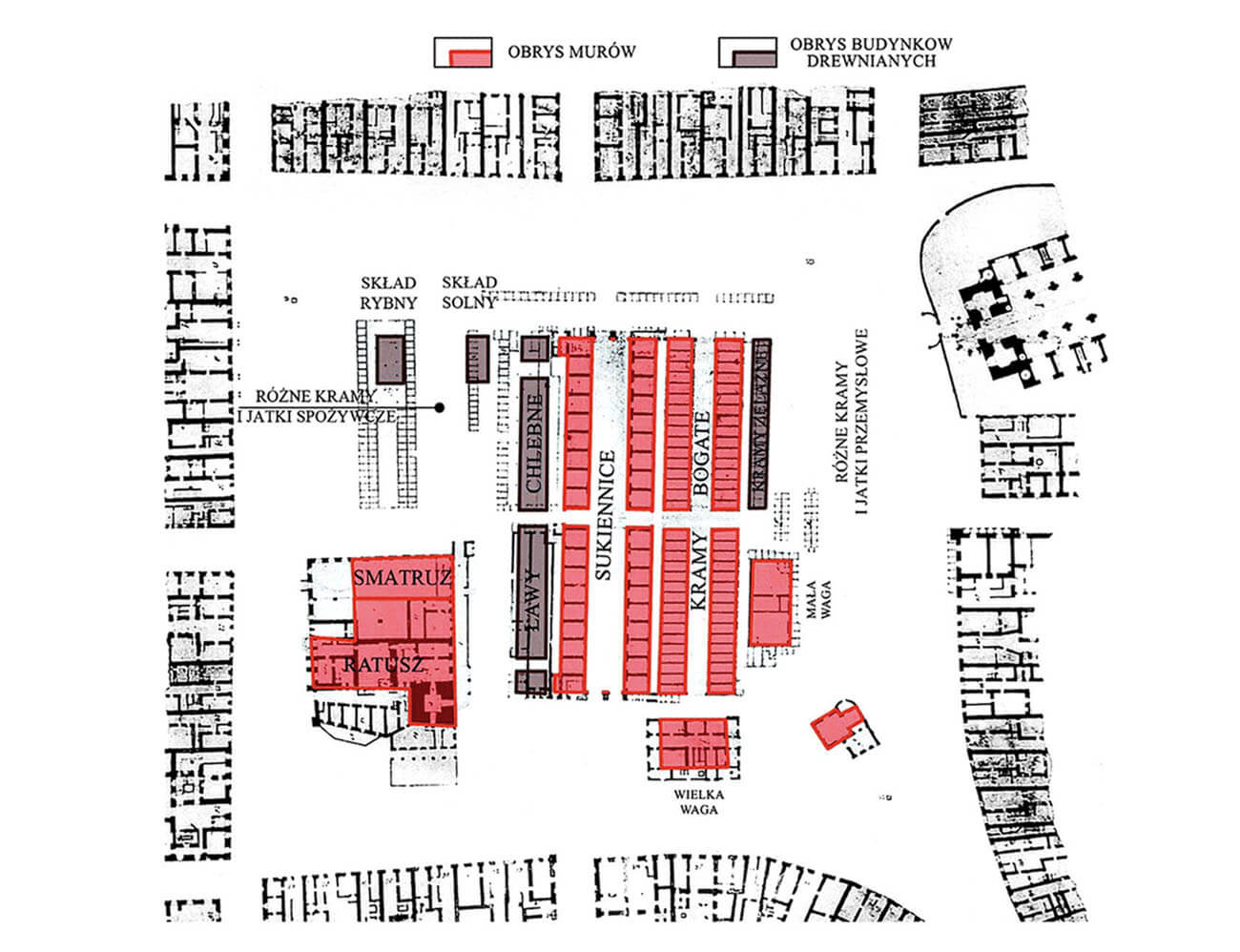

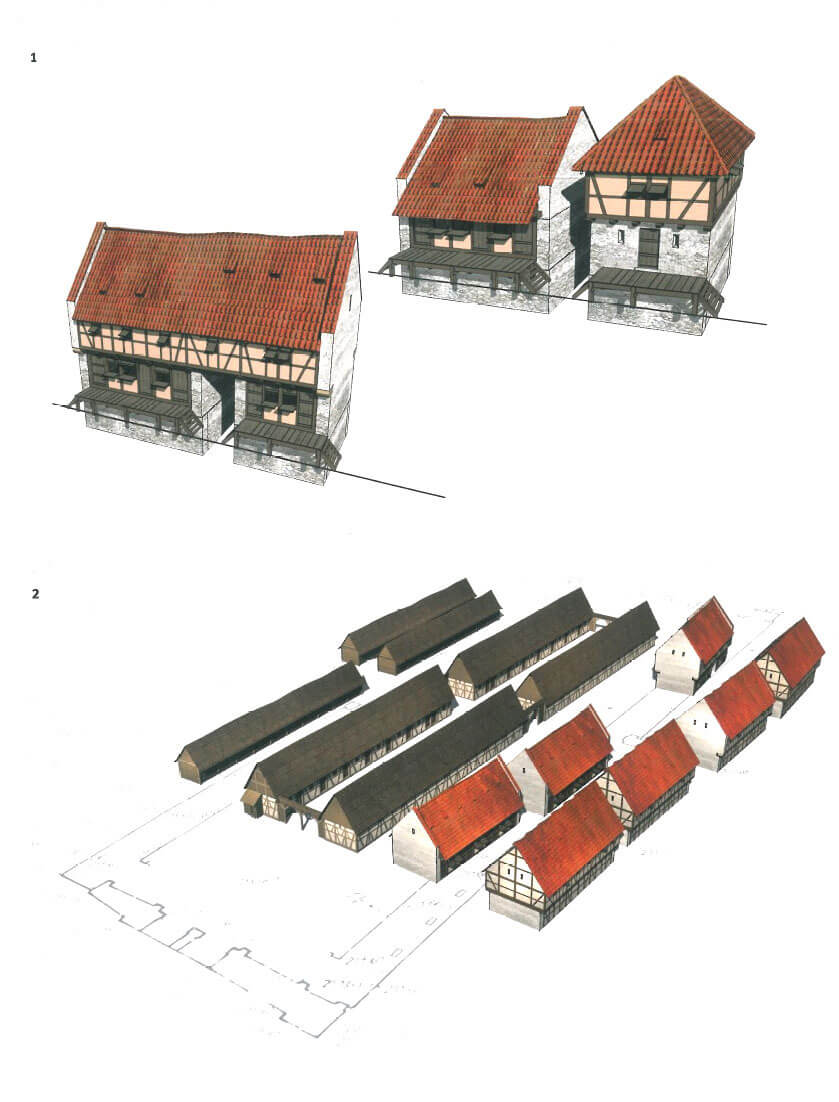

The oldest commercial buildings from the second half of the 13th century were built in the central part of the market, a space with sides about 200 meters long. It was a complex of buildings arranged in several rows with longer sides on the north-south line. In the middle there were two rows of wooden or half-timbered cloth hall buildings, on their western side there were wooden bakery stalls, and on the eastern side there were so called Bolesław’s Stalls. The double row of cloth hall buildings created a street in the middle, 5 to 6 meters wide, which was closed on both sides at night. Its northern end faced the free part of the market square, while the southern end faced the space enclosed on one side by the town hall and on the other by the Weigh Building with storage facilities for heavy goods such as copper, lead and silver. Behind it, in the corner, there was church of St. Adalbert, the only building from the times before the town was founded.

The market square was surrounded by a ring, a paved communication road, while individual buildings in the middle of the market square received a system of connecting roads, 3 to 7 meters wide. It ran in different directions and had an irregular layout, probably resulting from immediate needs. The most important of them, paved with cobblestones and enclosed by massive oak kerbs, allowed a heavier cart to pass through the muddy surface of the square. The ground, softened after heavy rains, was additionally covered with pavements made of sawn timber or covered with beaten straw mixed with waste. The surface of the market square constantly required hardening procedures, which is why major repairs were often carried out, consisting of demolition rubble thrown onto the square, as well as small stones. It did not create an even surface, but were pressed into the ground.

The so-called Bolesław’s Stalls consisted of seven buildings with basements, arranged in two rows parallel to the cloth halls, with a small square more or less in the middle. They were stone in the lower sections, and their upper walls probably had a half-timbered construction. The walls were built of limestone, appropriately selected in terms of size and shape, laid in even layers. Inside, the buildings were initially divided in the basement into three chambers measuring approximately 4 x 4.4 meters, whose height did not exceed 2.3 meters. They were probably covered with wooden ceilings, while the floors were made of limestone screeds or threshing floors. Square niches – shelves – were placed in the walls. Since the chambers did not have entrances in the walls, they must have been cellars accessible through holes in the ceiling. It were intended for storage, while trade took place in the upper rooms. Most likely in the first half of the 14th century, rectangular extensions were added to the eastern wall of at least one of the buildings.

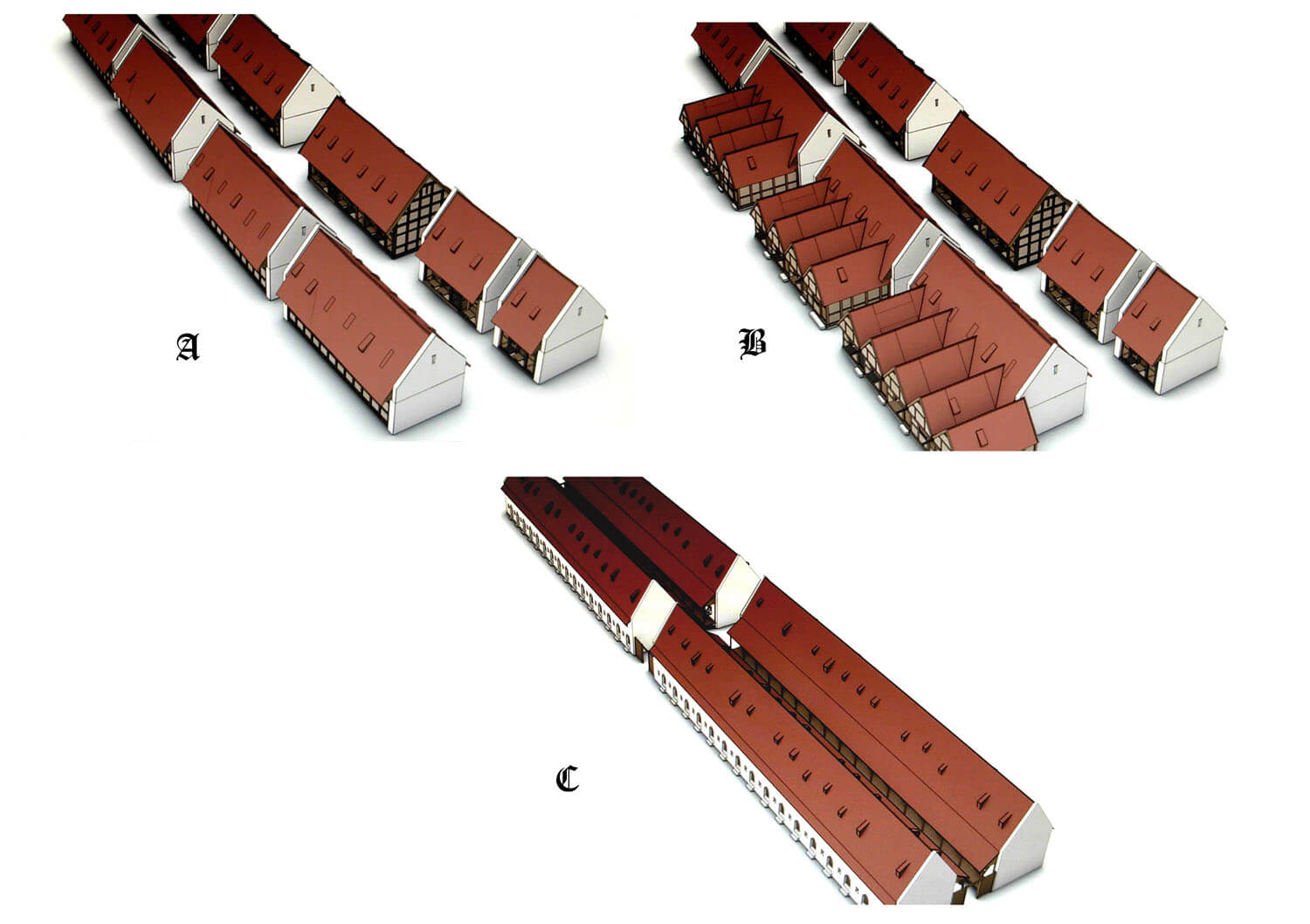

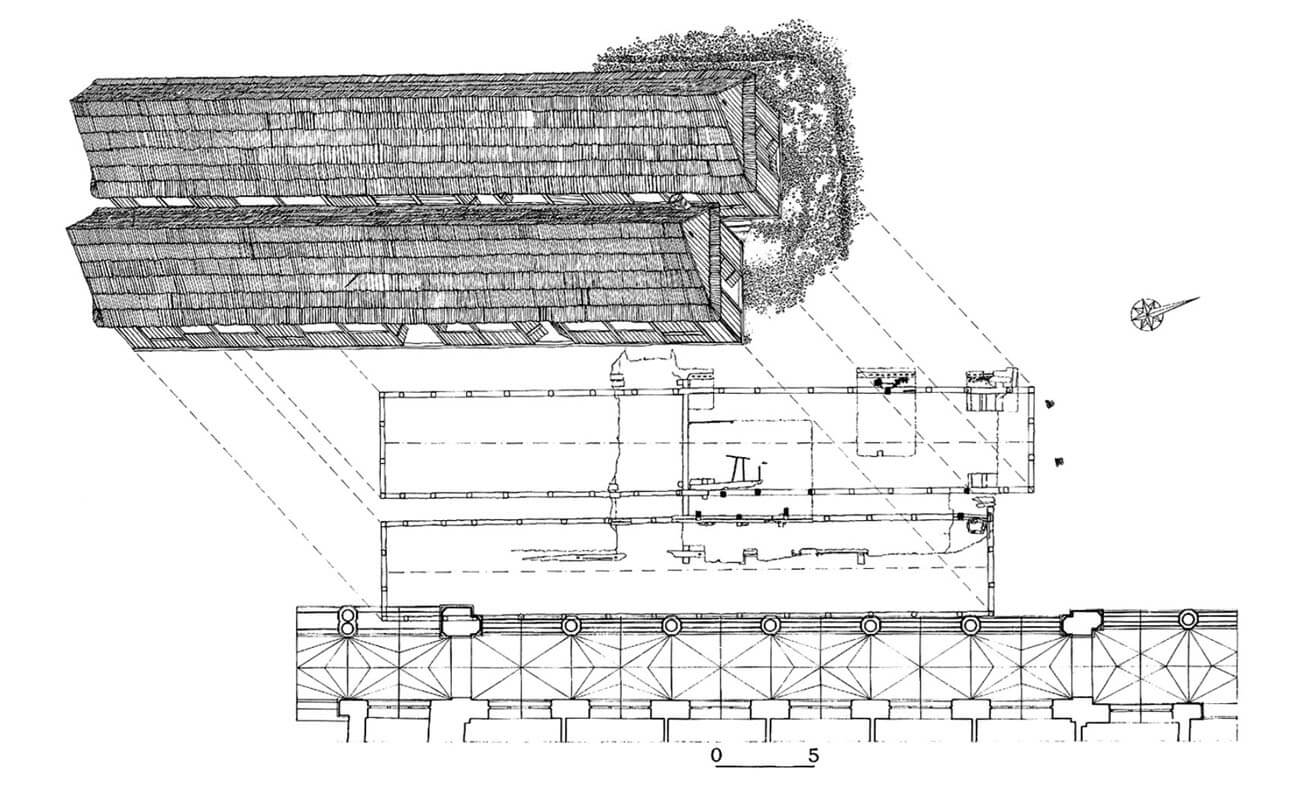

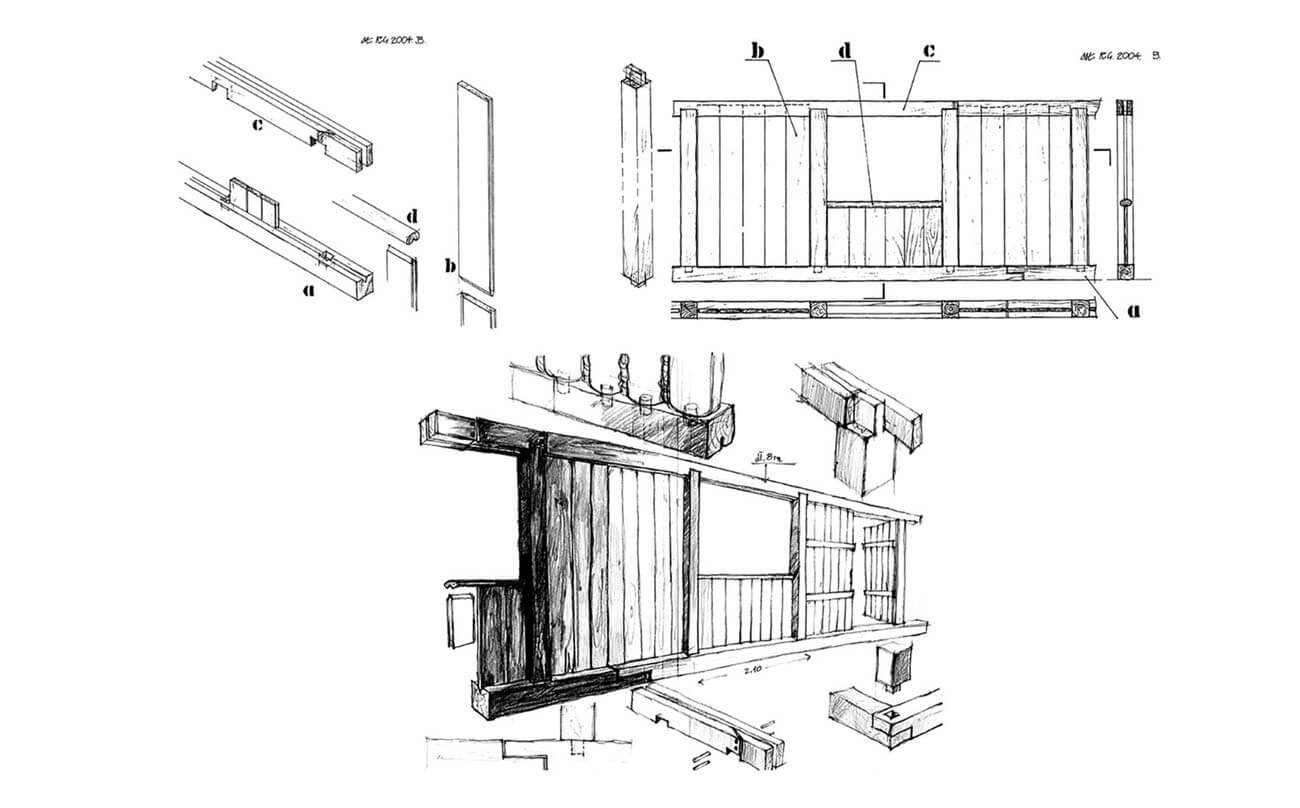

Western stalls from the beginning of the 14th century were about 5 meters wide, while their length reached several dozen meters. It were generally built in a timber-frame technique. Their ground beams were connected with a simple overlap and rested directly on the ground, without a foundation or other elements separating them from the ground. Only the corners had supports in the form of short transverse beams-joists, which played a stabilizing role in the most critical points. An additional element ensuring the stability of the connection were short, massive pins connecting the ground beam with the joist. In the corners of the stall, the beams were connected in a log technique. The vertical elements of the frame were posts, which supported the upper cap beams (beams taking the load from the ceilings or rafters). The posts were connected to the ground beams using tenons set in sockets hollowed out in the ground beams. The upper element of the stall wall structure – the cap beams, were connected with wooden pegs driven into previously made holes. The walls were made of vertical filling elements (boards, planks), cut in the lower part and set in a narrow groove running along the longitudinal axis of the ground beam, although the method of filling the frame of the stalls could have been slightly different for each phase. The long and narrow stall buildings were probably covered with double-pitched shingle roofs.

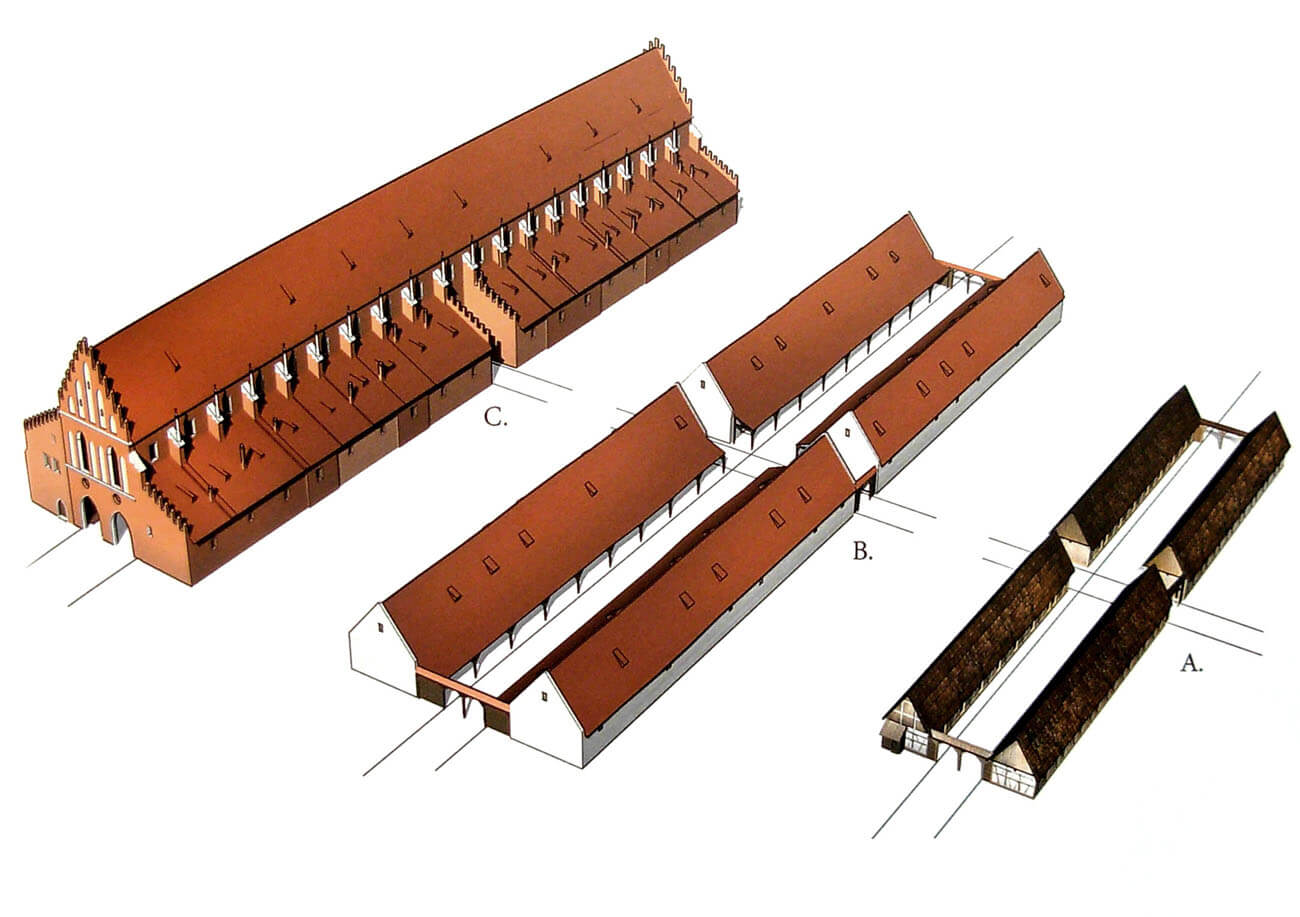

Around the middle of the fourteenth century, the middle part of the timber commercial complex was demolished, which was replaced by a slightly larger cloth hall, fully stone one, but roughly repeating the layout of the older building. Namely, they were four buildings arranged in two rows with streets crossing them on the north-south and east-west lines. The four entrances were probably equipped with wooden gates, locked at night to secure the stalls. Each building probably housed nine trading posts, which gave a total of 36 chambers. Each of them must have had an entrance opening and a window facing the street, the shutter of which, when opened, probably served as a counter on which goods were displayed.

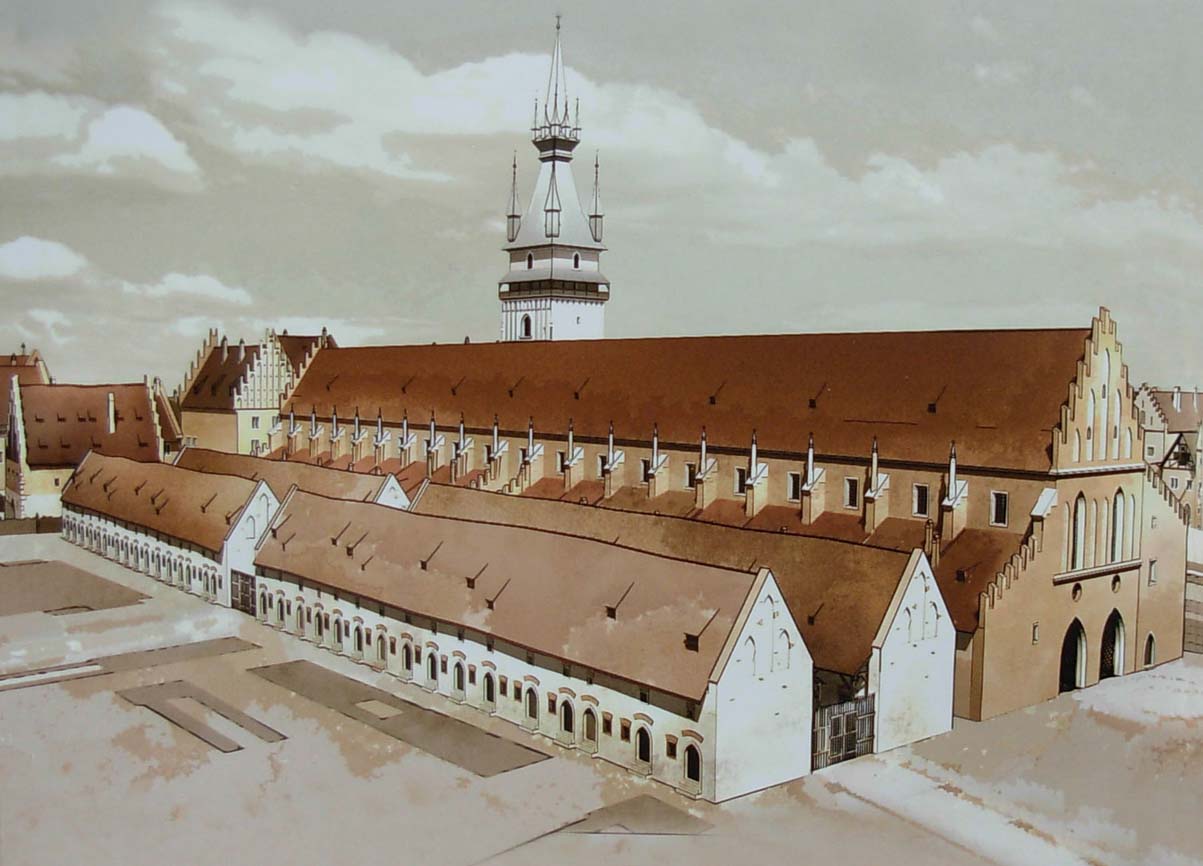

The oldest Weigh was a small timber building with a post-and-plank structure, hiding inside a weighing device and probably a weighing clerk’s flat in the attic. In the second half of the 14th century, a stone house of the Great Weigh was erected, situated on the site of an earlier wooden building. In the following years, it underwent transformations, and finally in the mid-15th century it had the shape of a two-storey building measuring 18.7 x 14 meters, with massive walls 1.2 meters thick, covered with a gable roof set on stepped gables. It was probably fenced, enclosing the area of the so-called Lead Market, small metal melting plants, warehouses, iron stalls and economic buildings. A pointed arch entrance from the east led inside, over 3 meters wide. The interior was divided into two rooms on the ground floor, of which the larger eastern one had an almost square plan and occupied two thirds of the ground floor. This room probably contained a weighing device in the form of two scales suspended from a horizontal arm about 5 meters long. Mainly metals were weighed on it: lead, copper and iron. On the first floor and in the attic there was a weighbridge’s apartment, a storage room for measuring instruments and warehouses, although most of the building had an open interior, divided only by pillars supporting the wooden ceilings.

In the second half of the 14th century or at the beginning of the 15th century, the two-storey Small Weigh House was built, a building on a rectangular plan measuring 26.5 x 11.7 meters. It was a two-storey house, perhaps the first floor initially being of half-timbered construction, and after the purchase of large quantities of stones and bricks in 1405, converted into brickwork. A characteristic feature of the building were the corbels on the longer eastern and western elevations, supporting the wider upper floor. The shorter sides of the building were closed with triangular gables, on which a gable roof was supported. Inside, the value of goods weighing less than 65 kg was estimated, such as wax, spices, minerals, soaps and resins. The lower storey housed a weighing device for trading in raw materials, and the upper storey housed the furriers’ guild seat.

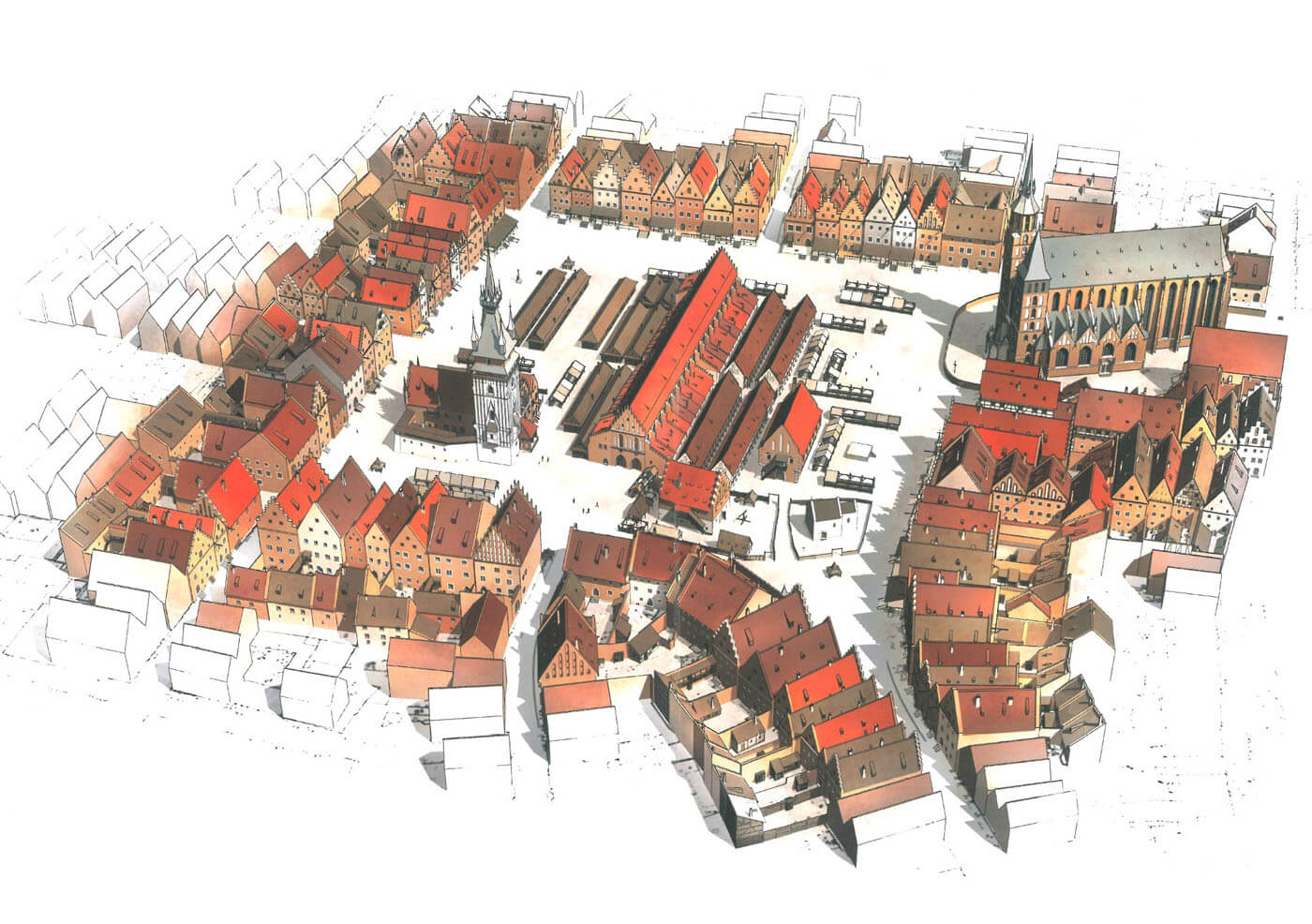

The second half of the 14th century saw the end of the communication system, characterized by routes running independently of the regular layout of the market square. Eventually, a regular and integrated layout of the main buildings was formed – the central cloth stalls, the eastern Wealthy Stalls and the western bread stalls, while for individual buildings a system of quarters was used with longitudinal streets on the north-south axis and a common intersection, basically coinciding with the original cross passage. The main axes of this layout were tried to be adapted to the streets intersecting the center of the individual frontages of the market (the street inside the cloth hall to św. Jana and Bracka streets, and the cross street to Sienna and Szewska streets). Moreover, there was a close connection between the new internal streets intersecting at right angles and the balks separating the groups of buildings, and the layout of the areas with smaller commercial buildings (markets). Such a layout had existed earlier, but it was less regular.

Gothic cloth hall from the end of the 14th century was an elongated building in the form of a basilica 104 meters long and 26 meters wide with a higher central part above the inner hall, covered with a high gable roof. On the southern and northern sides of the cloth hall, two ogival, closed gate portals were built, above which two tall and narrow ogival windows were pierced, separated by slightly smaller blendes. The upper part was formed from the north and south by Gothic stepped gables. The longitudinal walls, on the other hand, were reinforced with buttresses, which were decorated with slender pinnacles. Rectangular windows in stone frames were pierced between the buttresses in the spans’ axes, illuminating the main hall of the cloth hall. To improve communication, additional passages were created in the middle of the building’s length, on the eastern and western sides. On the west side, the cloth hall had two projections containing cloth cutting rooms.

Inside the cloth hall, on both sides of the main hall, along the longitudinal north-south axis, there were two rows of stalls, 7.5 meters deep, covered with mono-pitched roofs. There were 18 of them on each side, all covered with vaults and opened to the inside with pointed or semicircular portals 1.7 meters wide. All of them also had cellars covered with barrel vaults. The western row of shops was closed on the north and south by shearing rooms, where the cloth was divided before sale, of a size similar to the other chambers. Each row was separated by side entrances, creating quarters of 9 stalls. The central hall was 10 meters wide. It was probably open to the roof truss, as there is no records of floors above the shops.

From the east, starting from the beginning of the 15th century, the Cloth Hall was adjoined by the so-called Wealthy Stalls, built on the site of the less regular Bolesław’s Stalls, probably in order to make the buildings more orderly. These were stone rooms measuring 5 x 2.5 meters, where various luxury goods were traded. A total of 64 store chambers of Wealthy Stalls formed two rows separated by a roofless street, towards which they opened with portals and wide window openings connected with shutters – counters, on which goods were displayed after opening. Since individual stalls were individually owned, their development was uneven. Some cellars and the upper rooms were vaulted, others were covered with ceilings for a long time. The cellars were accessible almost exclusively from the sales premises.

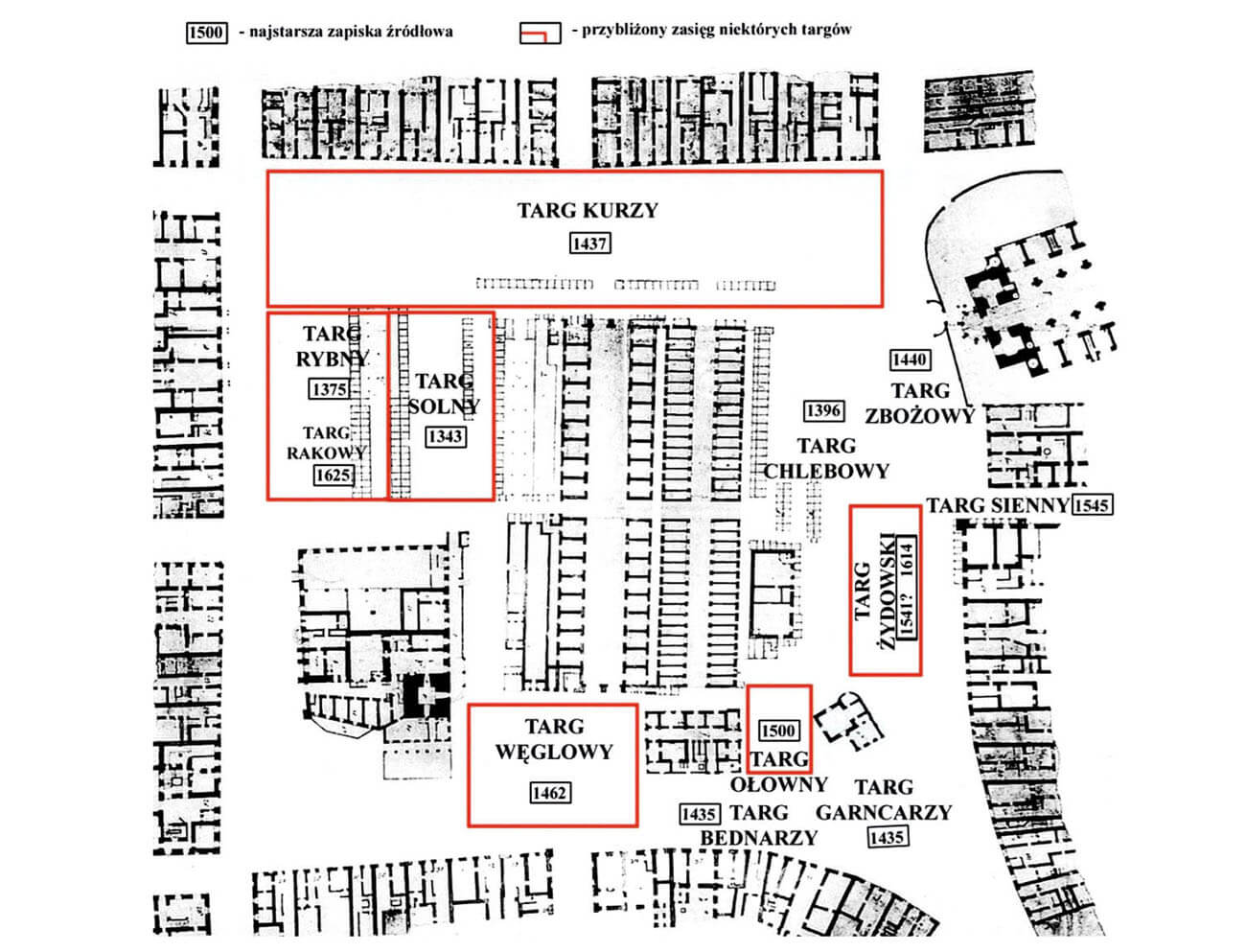

In the Middle Ages, the entire area of the market between the main buildings was filled with more or less dense, timber commercial buildings in the form of a series of one-story buildings forming sets of stalls, divided depending on the sold goods. For example, in the north-west quarter there was a salt and fish market, from the north was a chicken market, on the north-east side, opposite St. Mary’s Church there were iron and glass stalls, and a bread, grain and hay markets. On the south-eastern side there were hat traders, Jewish market, pottery market, cooper’s market and between the small Romanesque church of St. Adalbertus and the Great Weigh House – lead market. In the south-western part of the market shoemaker’s and tanner’s shacks were placed, and in the vicinity of the town hall – a coal market. Yet at the end of the 14th century, in the western part of the market square, probably behind the salt sellers, a market hall for petty traders was built (Polish: smatruz, German: Smetterhaus). Before 1463 it was moved near the town hall.

Current state

From among the numerous and varied commercial buildings of the Kraków market square, only the building of the cloth hall has survived to the present day. Today it is one of the most characteristic and best-known places in Kraków, as well as one of the outstanding works of the Renaissance. Older Gothic elements can be seen in places where they were not covered by early modern rebuilding, e.g. main ogival entrance portals, Gothic blendes visible through the Renaissance balcony, or pinnacles on buttresses at longer elevations and rectangular windows in stone frames arranged between them. In total, 28 medieval portals have been partially or completely preserved from the outside and inside.

Cloth Hall serve nowadays at the upper floor as the Gallery of Polish Painting and Sculpture from the 19th century, and the ground floor still houses trading posts, mainly filled with jewellery, souvenirs and handicrafts. In the basement, you can see relics of the medieval market square, as the ground level has risen by about 4.5 metres over the last five to seven hundred years. The museum called the Underground of the Main Market Square in Kraków, a branch of the Historical Museum of the City of Kraków, displays fragments of cobbled roads, relics of the first stalls, old waterworks, reconstructions of old craft workshops and many others.

bibliography:

Architektura gotycka w Polsce, red. M.Arszyński, T.Mroczko, Warszawa 1995.

Bojęś-Białasik A., Zaitz M., Kramy drewniane odkryte w 2004 roku po zachodniej stronie Sukiennic na Rynku Głównym w Krakowie, „Czasopismo Techniczne”, zeszyt 23, rok 108, Kraków 2011.

Buśko C., Z badań archeologicznych nad miastami południowej Polski. Rynek Główny w Krakowie w świetle prac przeprowadzonych w latach 2005-2007, „Archaeologia Historica”, 32/2007.

Buśko C., Dryja S., Głowa W., Sławiński S., Główne kierunki rozwoju krakowskiego Rynku Głównego od połowy XIII po początek XVI wieku, „Czasopismo Techniczne”, zeszyt 23, rok 108, Kraków 2011.

Firlet E., Opaliński P., Cracovia 3d, Via Regia – Kraków na szlaku handlowym w XIII-XVII wieku, Kraków 2011.

Komorowski W., Krakowska Waga Wielka w średniowieczu [in:] Późne średniowiecze w Karpatach polskich, red. J. Gancarski, Krosno 2007.

Komorowski W., Sudacka A., Rynek główny w Krakowie, Wrocław-Warszawa-Kraków 2008.

Kadłuczka A., Relikty monumentalnej zabudowy Rynku krakowskiego: ocena stanu zachowania i możliwości ekspozycji, “Ochrona Zabytków”, 48/1 (188), 1995.

Marek M., Cracovia 3d. Rekonstrukcje cyfrowe historycznej zabudowy Krakowa, Kraków 2013.

Opaliński P., Rekonstrukcja cyfrowa infrastruktury architektonicznej Rynku krakowskiego w XIV i XV wieku, “Krzysztofory”, nr 28, część 1, Kraków 2010.