History

The abbey in Jędrzejów was founded in 1140, as the first Cistercian monastery in Poland. It was established by representatives of the powerful Jaksa-Gryfit family, who brought monks from distant Morimond in Burgundy. The new foundation was named Morimondus Minor, or Morimond the Smaller. When the Cistercians organized a settlement in the village of Brzeźnica, it was later called Jędrzejów (“Andreovia”) after the saint patron of the East, St. Andrew the Apostle. The foundation process was primarily initiated by the Kraków canon Jan Gryfita and his brother, the Kraków Palatine Klemens of Klimontów. They endowed the monastery from their own inheritance and obtained the consent of the Kraków bishop Radost to transfer the Brzeźnica parish church and the tithes to the abbey. After completing the preparations in 1146, Jan Gryfita, already as the bishop of Wrocław, began to apply to the general chapter of the order for a monks to be sent, which probably reached Małopolska in 1149, under the leadership of Abbot Nicholas. In 1153, Jan issued a foundation privilege, which summed up the foundation’s work to date and legally secured the monastery’s assets. Shortly afterwards, the monastery received an immunity privilege from Prince Bolesław the Curly, i.e. exemption from tributes, along with the right to organize a market.

Initially, the monks used a small Romanesque church under the invocation of St. Adalbert, which had existed in the village since around 1108. After reconstruction and adaptation to new needs, it was re-consecrated in 1167. At that time, the monastery also received new endowments from the Bishop of Kraków Gedko, princes Mieszko the Old and Kazimierz the Just, and the estate of the childless knight Śmił Boędztowic. At the turn of the 12th and 13th centuries, the most important eastern wing of the monastery was built, the church chancel with a transept and four chapels, and the external walls of the aisles, which were added to the older church on the western side. The building was consecrated in 1210 by the Bishop of Kraków and chronicler Wincenty Kadłubek. He resigned from the dignity of the Bishop of Kraków seven years later, and in 1218 entered the monastery of Jędrzejów, where he spent the last five years of his life as a monk and was solemnly buried. The election of Wincenty in the long run, together with the emerging reputation of sanctity and cult, significantly increased the prestige of the abbey.

In the first half of the 13th century, Abbot Theoderic, who served between 1213 and 1246, took care of increasing the abbey’s lands and new privileges, and may have also finalized the construction of the monastery basilica or cloister. At the same time, Theoderic took an active part in church-political congresses and mediation missions, and was involved in political life. After the death of Leszek the White in 1227, when the struggle for the Kraków began, battles took place near Jędrzejów. For this reason, the abbey was supposed to be occupied by armed men and fortified, although this most likely only concerned the construction of ramparts and the light wooden structures. According to the chronicler Jan Długosz, the Mazovian knights fortified in the abbey, while the troops of the allied princes Henry the Bearded and Bolesław the Chaste fought a guerrilla war against them. A much greater threat to the abbey and its property came with the Mongol invasions. In 1241, the their route most likely bypassed Jędrzejów, but already in the winter between 1259 and 1260, the Jędrzejów abbey and its property were devastated, along with the monasteries in Koprzywnica, Sulejów, and Mogiła. The reconstruction was carried out with the support of Prince Bolesław the Chaste, under whom Jędrzejów (“Ciuitati Andrzeow”) received charter in 1271.

Construction work in the monastery did not cease during the Gothic period. At the turn of the 14th and 15th centuries, construction was carried out in the nave of the church and at the claustrum. When Mikołaj Odrowąż of Rembieszyce became abbot in 1447, he set a plan for the reconstruction of the abbey, including the construction of a cloister and the completion of work on the nave, he also erected abbot’s house with a hospice. The works most probably started in 1448, when the papal legate, at the request of the abbot, announced that although according to custom and the law of the order women were forbidden to enter the church, due to the need for renovation and construction works, this restriction was abandoned on selected holidays for people giving alms. At the end of the reconstruction, the abbot invited famous masters to finish, decorate and work on the abbey’s art, including Veit Stoss and the Kraków goldsmiths: Nicholas Kregler and Nicholas Breimer. They worked until the 1480s, because in 1487 the abbey undertook to pay Veit 70 Hungarian florins remaining from the amount due for sculptures made and donated to the monastery church.

In the mid-17th century, the Swedish Deluge contributed to the economic ruin of the abbey, during which it was plundered. The difficult situation was aggravated by the fire of 1726. The church burned down, its walls were weakened and the vault was destroyed. The reconstruction carried out a few years later gave it a late Baroque appearance. Another fire in 1800 turned out to be worse for the monastery buildings, as the archive and the library burned down. In 1819, the Cistercian Order was suppressed on the territory of Poland, and a few decades later, a Russian male teacher’s seminar was established in the monastery walls.

Architecture

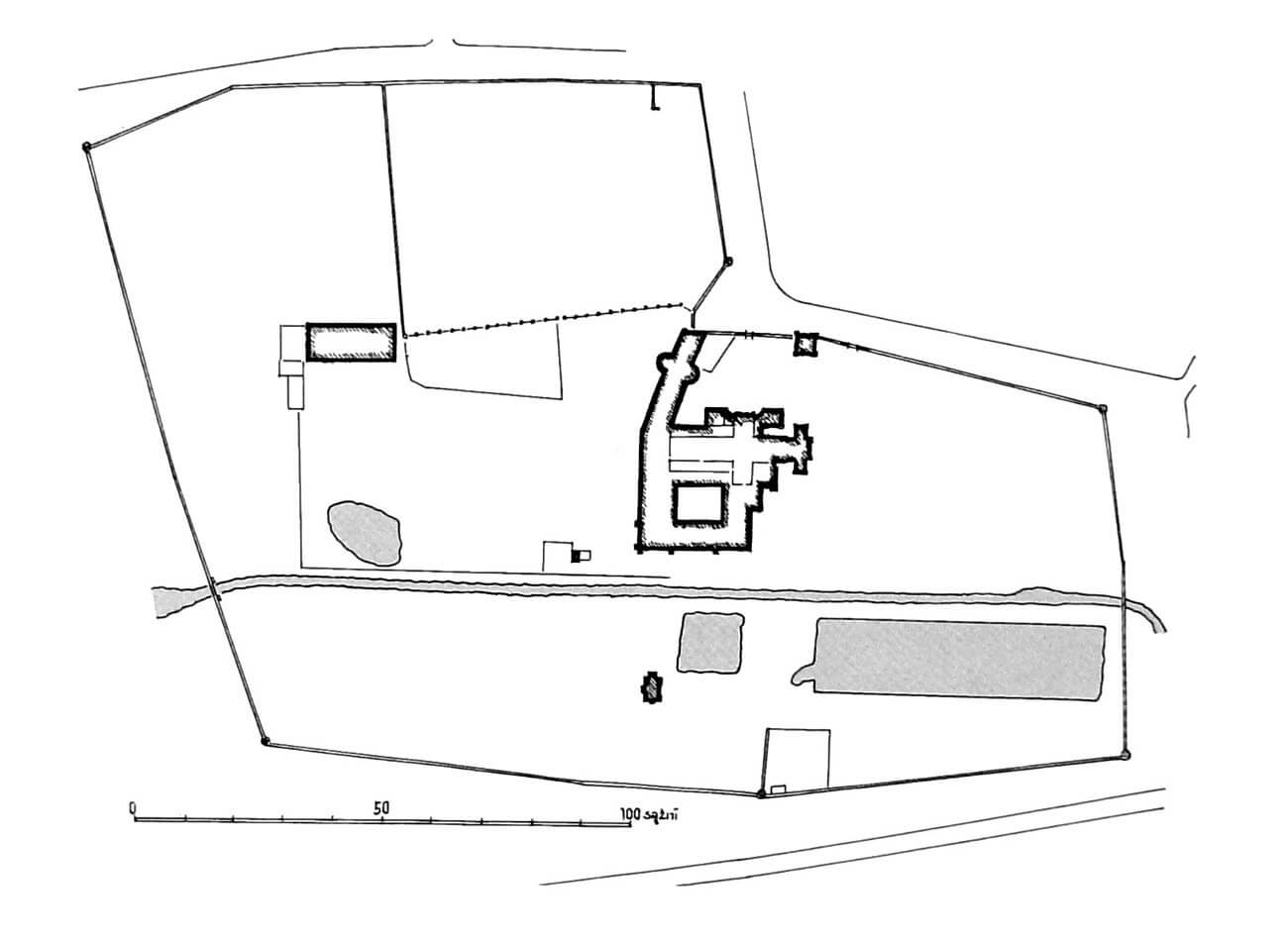

The abbey was founded on the northern side of the Brzeźnica River, near the village of the same name, which peasant buildings were moved east after the monks arrived, where the settlement of Jędrzejów was established, and west towards the settlement of Sudół. The far-marked borders were to ensure a distance between the monastery and the village. The center of the abbey was the existing Romanesque church of St. Adalbert, then incorporated into the monastery basilica connected with the buildings of the three-winged cloister. Next to it was an external utility courtyard, a monastic cemetery, an infirmary, a guest house, as well as monastery buildings such as a granary, a mill, a forge, a brewery, gardens and orchards. This area was probably surrounded by a wall or rampart, and the entrance to it led through a gate or gatehouse. The riverbed and stream were subjected to major engineering investments, creating a series of ponds using natural depressions, backwaters and water holes. Ponds were fed by both river waters and ground sources. In this way, reservoirs were created, placed along the riverbed or directly on its axis, feeding water mills and smaller channels.

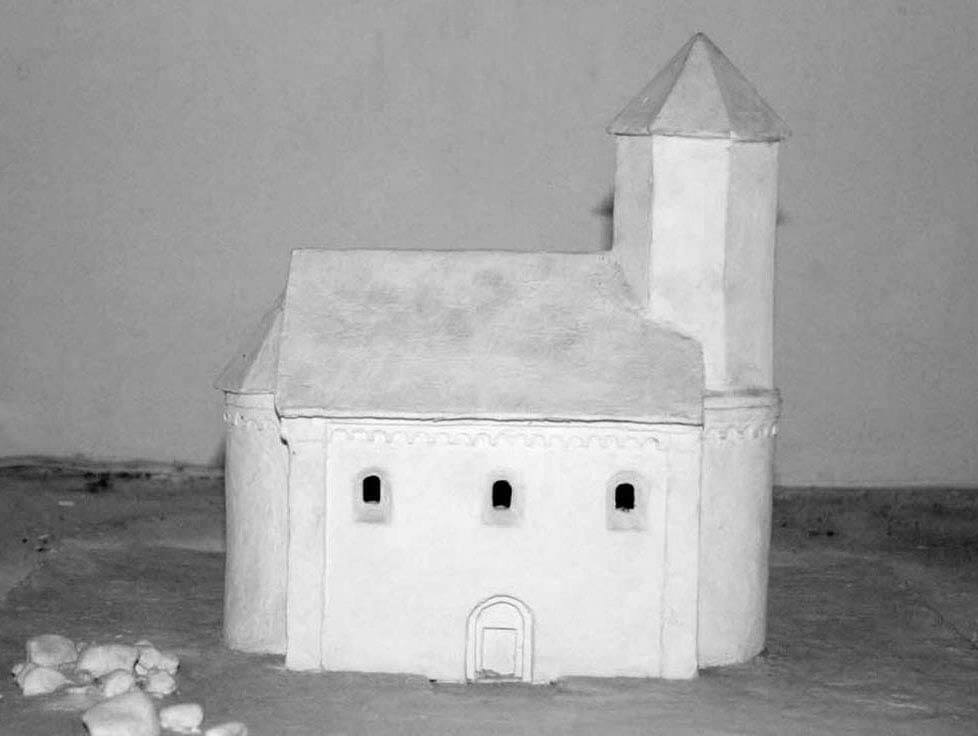

The pre-Cistercian church from the 12th century was built of limestone in the opus emplectum technique, with the use of sandstone ashlar in structural elements (corners) and architectural details (windows, portal), as well as of unworked sandstone used in the foundations. An aisleless nave with dimensions of 6.3 x 10 meters on the west side had an apse with a diameter of 3.3 meters, divided into two floors. The upper one was a gallery extended deep into the nave with an open arcade and supported on a pillar, the lower one was connected to the nave by a narrow portal. Above the apse there was a tower with an unusual seven-sided cross-section. The facades were decorated with corner pilaster strips and an arcaded frieze under the cornice. The eastern part of the nave was also closed with an apse, 3.6 meters in diameter, thanks to which the church was very similar to the Romanesque church in Prandocin.

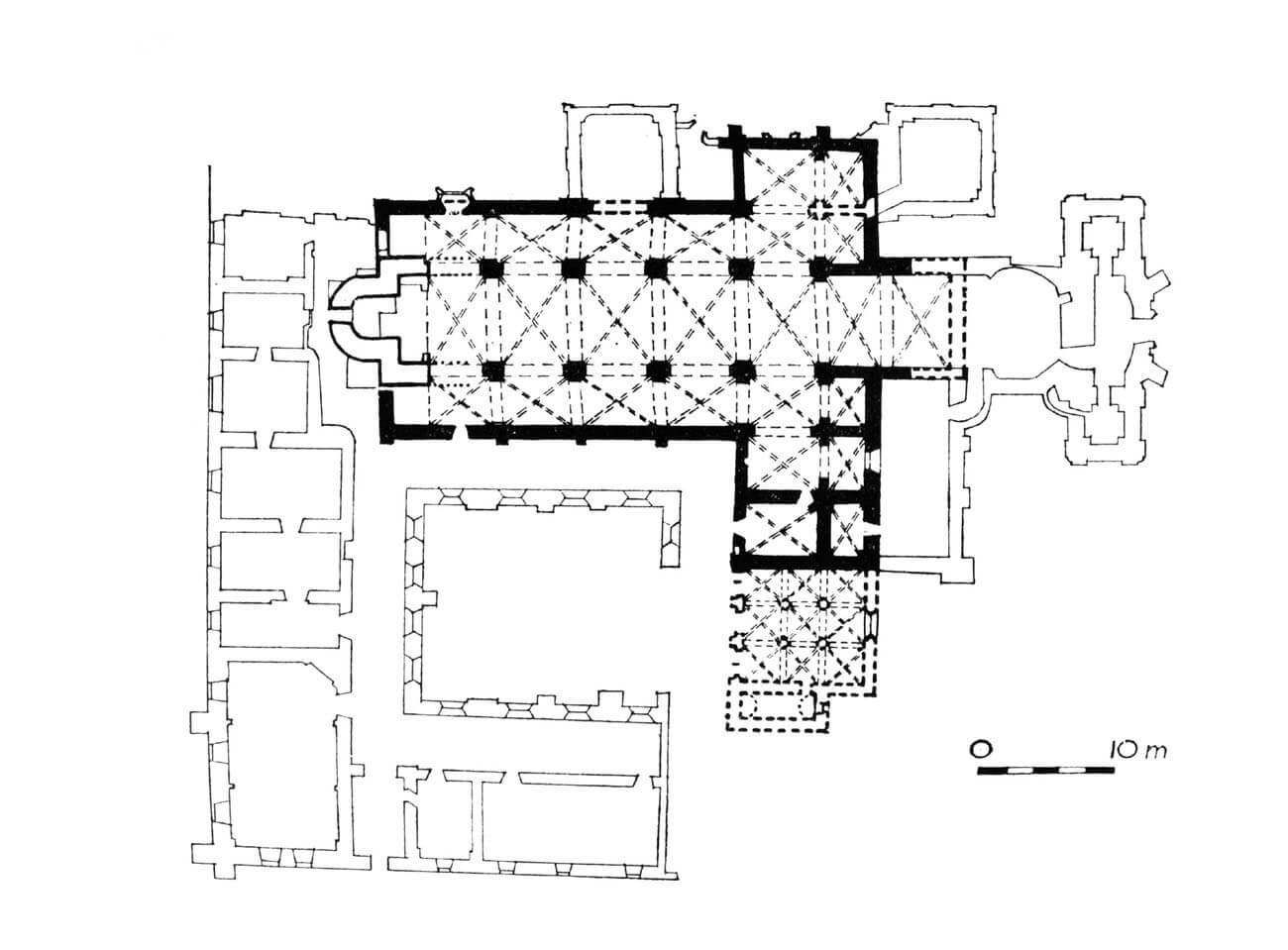

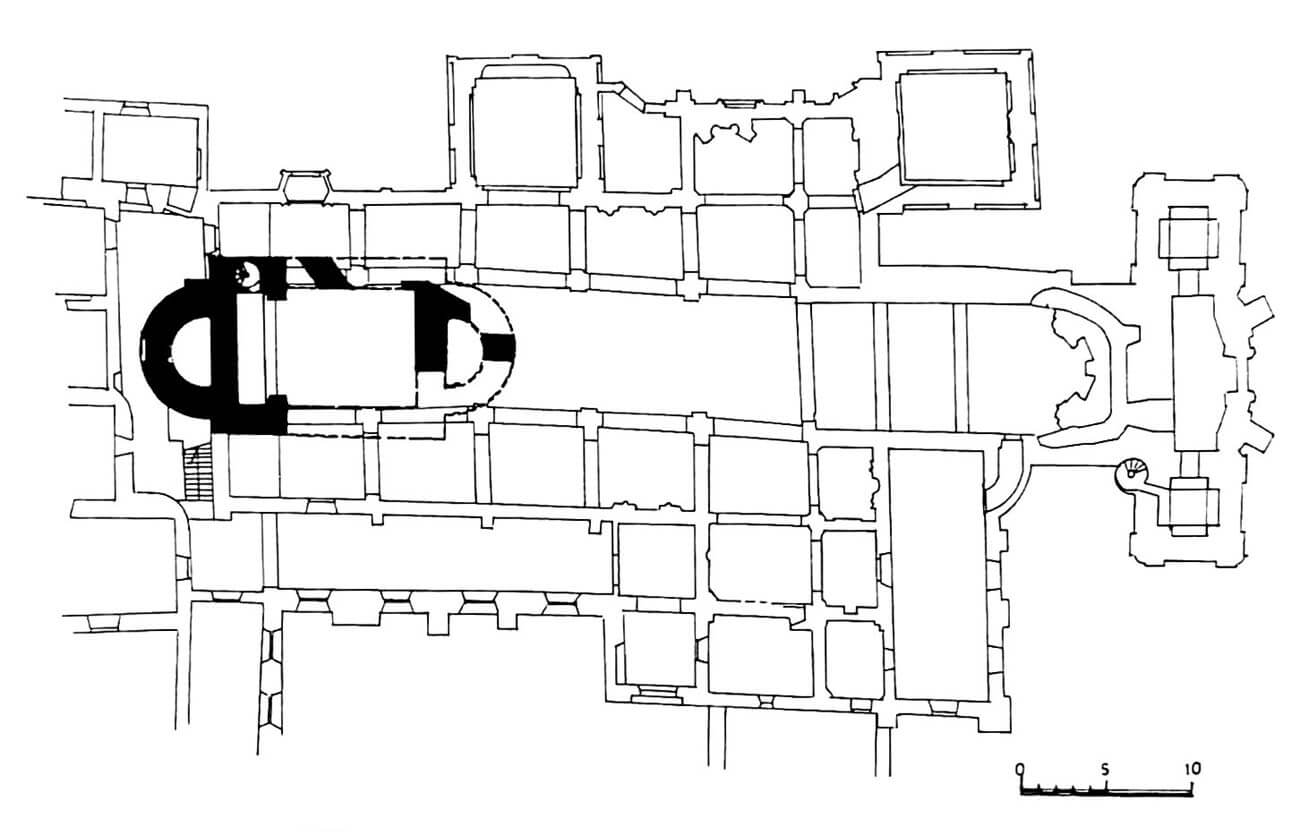

According to the Cistercian scheme, the medieval monastery church was a basilica with central nave, two aisles, a transept, a straight ended, two-bay chancel flanked from the north and south by double chapels and with a tower western façade, created by merging an older Romanesque church. Length of the church was 38.5 meters, the width of the nave was 16.8 meters, (including the central nave 5.9 meters), and the chancel 7.3 meters. The dimensions of the transept were 5.6 x 27 meters. The church was built of large, finely worked blocks of sandstone with faces decorated with delicate cuts. Few of the blocks were marked with stonemason’s marks. The external elevation of the church in the southern aisle was pierced by a row of semicircular, splayed on both sides windows. Similar ones were probably used in the central nave, in the western walls of the side aisles and in the southern wall of the chancel. In the west façade of the nave (in the base of the tower of the former pre-monastery church) a rosette window with richly moulded jambs was pierced. Inside, the nave consisted of four rectangular bays, with the western bays of the central nave covering the relics of an older church, from which the western part was left with a seven-sided tower on a semicircular base. The vaults of the nave, chancel and transept were probably cross-ribbed supported on wall-corbels (one of the earliest of this type in Poland), whereas in the case of transept chapels the cross vaults without ribs were used.

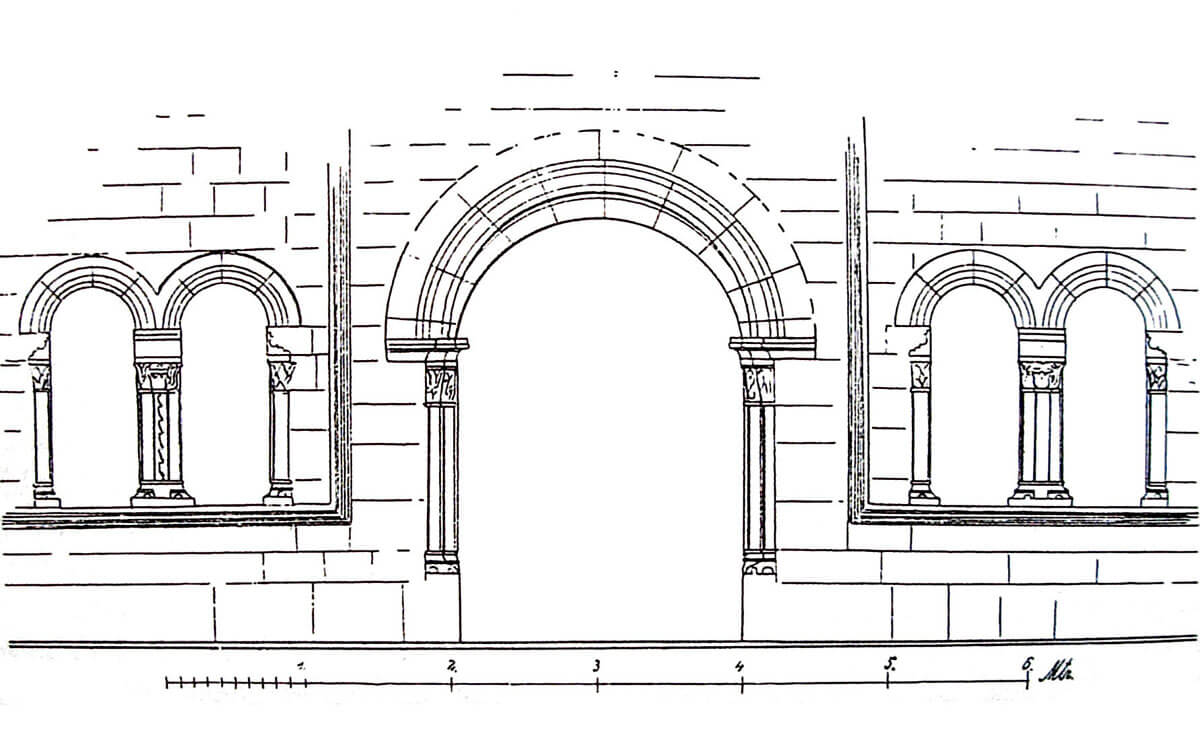

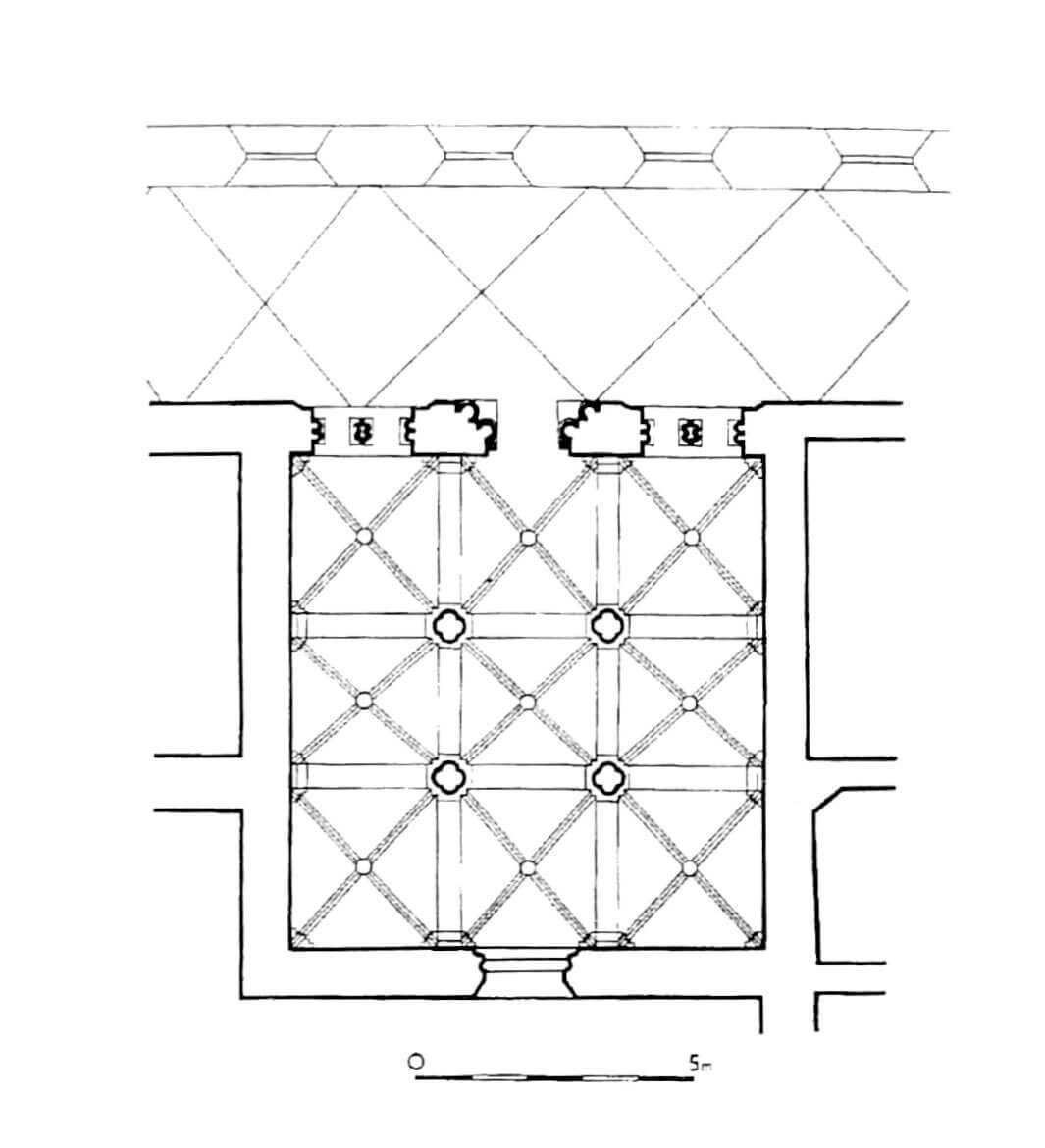

On the south and west sides of the church there were monastery buildings surrounding the cloister. The eastern wing with an internal width of 8.7 meters (external 11 meters) housed the sacristy from the north, then the chapter house, stairs to the first floor under which the barrel vaulted prison was located, then the lobby and day room. The sacristy was topped with three rectangular bays of the rib vault without bosses. The entrance to it from the cloister was covered with a monolithic lintel in the form of a pentagonal tympanum. The chapter house with an interior on a square plan measuring 8.8 x 8.8 meters consisted of nine square vaults based on four pillars and wall corbels, supporting the rib vaults separated by buttresses. It was particularly richly decorated, because it was here that the main matters of the abbey were held every day. The monks sat on benches against the walls, and in the middle there was probably a lector’s desk. In the western wall there was a semicircular portal without a tympanum, flanked with open-works with semicircular arches, supported in the middle on beam pillars composed of four columns and on two side on semi-columns. Column heads, corbels and bosses of the chapter house were covered with floral decoration enriched with a string motif. These details were originally covered with red, green, yellow and maybe blue polychromes. From the east, the chapter house was probably illuminated by three windows, of which the middle one could be a moulded oculus. Only from chapter house it was possible to get to the neighboring prison, illuminated by a single, small window. Day room, that is a room for manual work, used especially in winter, received dimensions of 9 x 7 meters. It ended the east wing from the south. Using the slope of the area towards the Brzeźnica River, two cellars 6.3 x 3.9 meters each were placed under the day room, covered with barrel vaults.

The east wing upper floor was occupied by the brothers’ bedroom, a dormitory, erected in contrast to the lower part using bricks. It probably occupied most of the space of the east wing and was connected directly to the southern transept, where by means of night stairs the brothers went to evening prayers. Mostly the dormitories on both sides were illuminated by small windows that corresponded to individual sleeping places. In the west, windows overlooked over the mono-pitched roof of the cloister to the garden, while in the east, the monastery grounds. The beds since the 12th / 13th century were separated by wooden or half-timbered partitions, creating separate cabins, sometimes obscured by curtains, but always leaving the passage through the center of the dormitory. In addition, on the upper floor of the east wing there was a cross-ribbed two-bay room, occupying the space between the two chapels at the transept. Initially, it probably served as the abbot’s chamber, and later as a library. On the opposite side of the wing, at the end of the room, there were usually passages to the latrines, located on the first floor, above the sewer. Often, for hygienic reasons, latrines were built at a distance from the monastery wing and connected to it by means of a porch hung on arcades.

The southern wing housed a large, three-bay refectory measuring approximately 9.5 x 19 meters, positioned as in most Cistercian monasteries perpendicular to the axis of the wing. It had a lower storey covered with six bays of rib vaults, where a partially vaulted channel was placed supplying water to the kitchen and lavabo, and then draining sewage. The refectory was built of bricks, probably already around the mid-thirteenth century, as evidenced by the archaic structure of the vaults with arch bands between the bays and ribs with a rectangular cross-section. The refectory was initially a free-standing building, strengthened from the outside by diagonal buttresses in the corners and straight buttresses in the places of the vaulted bays. During the late Gothic period, it was connected to other rooms of the southern wing, among others, a kitchen and perhaps a calefactory, i.e. a room heated throughout the winter, in which the brothers could warm up as the only hot one place in the monastery. Inside the refectory there should be a opening for serving dishes from the kitchen and a lector’s desk from which it was read during meals.

The west wing was built of unworked stone, but nothing more is known about its arrangement or purpose (in Cistercian monasteries these wings were most often intended for lay brothers and for the pantry and cellars – cellarium). All wings were connected by a late Gothic cloister with high ogival arcades, which provided connection to most of the monastery’s chambers without leaving the weather. In the center there was a patio, a monastery garden, a place for growing herbs and vegetables, as well as rest. In the middle of it was a well, carefully walled with stone blocks. Outside the compact area of the cloister, in the 15th century, a Gothic building, the abbot’s house, was built on the north-west side of the claustrum. It was a multi-story building, originally probably freestanding, not connected to the rest of the monastery.

Current state

The entire monastery was heavily rebuilt in the 18th century by adding a two-tower, Baroque façade to the chancel, the addition of chapels from the north, and a complete change of the church’s interior and furnishing. From the Middle Ages a semi-circular stone tower in the central part of the monastery and a fragment of the old façade, still from the pre-cistercian church from before 1118, are preserved. Next to it is a Romanesque portal and a small window from the early 13th century and in the eastern bay of the nave from the cloister side ogival portal and window with a well-preserved tracery. Also, most of the perimeter walls of the medieval basilica have survived, partially transformed chapels at the transept along with relics of old internal articulation. On the ashlar of the church walls, within the cloister, several dozen inscriptions and drawings engraved or drawn with coal are visible. Some of them, presenting ornamental, geometric and floral motifs are probably patterns for stonemasons who make bosses and capitals. Of the monastery buildings, the sacristy and three wings of the cloister have survived only.

bibliography:

Jarzewicz J., Kościoły romańskie w Polsce, Kraków 2014.

Łużyniecka E., Kunkel R., Świechowski Z., Architektura opactw cysterskich. Małopolskie filie Morimond, Wrocław 2008.

Świechowski Z., Architektura romańska w Polsce, Warszawa 2000.

Sztuka polska przedromańska i romańska do schyłku XIII wieku, red. M. Walicki, Warszawa 1971.

Zdanek M., Jędrzejów w wiekach średnich, Kraków 2022.

Zdanek M., Klasztor cystersów w Jędrzejowie w drugiej połowie XV wieku, “Roczniki Historyczne”, LXXVIII/2012.